Overview

Historian E. James West interviews novelist and West Virginia native Ann Pancake, author of Given Ground (Lebanon, NH: The University Press of New England, 2001), Strange as this Weather Has Been (Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint Press/ Shoemaker & Hoard, 2007), and Me and My Daddy Listen to Bob Marley (Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint Press/ Shoemaker & Hoard, 2015).

Introduction

As a child, Ann Pancake dreamed of escaping from West Virginia. Achieving this goal as a young adult, however, only served to strengthen her emotional and cultural bonds to the Mountain State. Over the last two decades, Pancake has become one of the leading Appalachian writers of her generation. Her work addresses many themes in its concern with the everyday lives of West Virginians and the making of regional and national identities. Pancake engages the history of Appalachia and its people, revealing the impact of deindustrialisation, rural poverty, and environmental destruction.

Ann Pancake, Seattle, Washington, 2014. Photograph by Catherine Alexander. Courtesy of the author.

Published by the University Press of New England in 2001, Pancake's first collection of short stories, Given Ground, earned the praise of Elizabeth Judd in the New York Times for "depicting an ignored part of the country with a clear and admiring eye." Pancake, wrote Judd, possesses the "unusual gift for portraying difficult lives with a plain-spoken accuracy that makes them seem suddenly exceptional."1Elizabeth Judd, "Books in Brief," New York Times, August 12, 2001. Six years after Given Ground came Pancake's first novel, Strange as this Weather Has Been.2Ann Pancake, Strange as this Weather Has Been (Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint Press/ Shoemaker & Hoard, 2007). Widely praised for its literary vision and striking language, the novel presents an unflinching portrait of a poor West Virginian family living in the shadow of a strip mine. Writing in the Iowa Review, Jeremy Jones declared Strange as this Weather Has Been to be "a true novel . . . brimmed with beauty and poetics but aimed at change and justice."3Jeremy Jones, "Ann Pancake's STRANGE AS THIS WEATHER HAS BEEN," Iowa Review, January 8, 2011. Pancake's most recent collection of short stories, Me and My Daddy Listen to Bob Marley, arrived in 2015 to considerable acclaim; Publisher's Weekly recommended it as a "gritty, stylish assembly."4"Me and My Daddy Listen to Bob Marley," Publisher's Weekly, December 8, 2014.

Cover of Ann Pancake's Strange as this Weather Has Been (Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint Press/Shoemaker & Hoard, 2007). Cover design by Gerilyn Attebery featuring Jeff Chapman-Crane's The Agony of Gaia, which was created in response to the devastation caused by mining techniques such as mountaintop removal.

Pancake's distinctive style and incisive portraits of Appalachian life have led to acclaim and awards. West Virginian novelist Jayne Anne Phillip characterised Pancake as "Appalachia's Steinbeck." Georgian writer and environmental activist Janisse Ray has described her writing as "shockingly pure, like holding gold in your hands." For critics such as Dan Chaon, Pancake's work is "astonishing . . . tender, alive, full of heart and empathy but never sentimental, full of clenched drama and secrets and surprises but always subtle."5Quotes taken from Pancake's personal website, http://www.annpancake.blogspot.com. Pancake has received the Bakeless Literary Award for short story writing, a Whiting Award, an NEA grant, a Pushcart Prize, and creative writing fellowships from Washington, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania. Strange as this Weather Has Been won the 2007 Weatherford Award by the Appalachian Studies Association, was a finalist for the 2008 Orion Book Award, and was chosen as one of Kirkus Review's ten best fiction books of 2007. Most recently Pancake was chosen as the first recipient of the Barry Lopez Visiting Writer Fellowship at the University of Hawaii.

This interview considers the formative role of Pancake's childhood in Appalachia, and the impact of her time in college and working abroad on her literary aesthetic. Pancake considers her work from a variety of perspectives, tackling questions of violence, historical memory, race, and culture, before discussing the publication of her most recent collection and her plans for the future.

[This interview took place on Wednesday, March 9, 2016 with supplementary correspondence in July and October. It has been edited for clarity. Many thanks to Ann Pancake for being so generous with her time and her willingness to talk about her life and work. Thanks also to the Hagley Museum in Wilmington, Delaware, for providing the setting and the equipment for this discussion.]

Growing Up

JAMES: Hi Ann. Thanks for taking the time to talk with me. Perhaps you can start by offering a brief introduction to readers who might be unfamiliar with your life prior to the publication of Given Ground.

Welcome to Romney, Romney, West Virginia, November 13, 2011. Photograph by Flickr user Ron Cogswell. Creative Commons license CC BY 2.0.

ANN: Sure. Until I was eight years old I lived in Summersville, West Virginia. That's in Nicholas County, an important coal producing part of the state. That was the period of my life in which I became aware of the coal industry and of strip mining, partly because we could see strip mining from our house, and my dad talked to me about strip-mining and the damage it caused. When I was eight we moved to Romney, West Virginia, which is where my dad's family has been for a couple hundred years, and it's agricultural—there's no coal up there. I lived in Romney until I was eighteen, and then I went to West Virginia University.

When I graduated with my BA at twenty-two, I went overseas, partly because I didn't think there was anything to write about in West Virginia, and also because I didn't have a job and the unemployment rate was really high in West Virginia. I got a job in Japan and taught there for a year. In my twenties I also taught in American Samoa for two years and I taught in Thailand for almost a year. I did a good bit of travelling in Asia and the South Pacific. I got my MA in English at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and shortly after, went into the doctorate program at the University of Washington, where I was from 1993 until 1998.

JAMES: I've read about your wanting to get away from West Virginia when you were growing up.

Center of Romney, WV, Romney, West Virginia, April 24, 2004. Photograph by Flickr user Taber Andrew Bain. Creative Commons license CC BY 2.0.

ANN: By the time I was a teenager I really wanted to see other parts of the world and get out of West Virginia. I thought the state was boring and very limited . . . at the same time, my whole life I'd had this highly complicated relationship with it because I was also much prone to homesickness. So I was both deeply attached to West Virginia but also feeling very much the pull to see places outside. I still have that conflicted relationship. Appalachia has an almost mysterious pull on people who grow up there, even on people who aren't native but who have lived there a long time. As a teenager, I felt very strongly the push/pull relationship with West Virginia I feel still.

JAMES: Do your siblings have the same fraught relationship with West Virginia?

ANN: Yes, I'd say the five of us who left the state do have a deep attachment that is also fraught. My only sibling who stayed is my brother who has a lot of addiction problems, which is why he will never leave. My sister, as I think you know, made a documentary film about mountaintop removal in West Virginia called Black Diamonds – she lived in Baltimore while she made it and lives in Philadelphia now, but she feels a profound connection to West Virginia like I do. We're all pretty attached to it. West Virginia is like no other place I've ever been, culturally. You can't find it or replicate it.

JAMES: One of your brothers is an actor and your sister is involved in film and documentary production.6Sam Pancake and Catherine Pancake. Ann and Catherine collaborated on the production of Black Diamonds, a 2006 documentary film about mountaintop removal and the fight for coalfield justice in West Virginia. Did your parents encourage you to develop an interest in the arts as children and was that typical where you grew up?

ANN: My parents did encourage us in the arts, and it was not typical in our community, but my parents both went to college, which was also not typical. Only a small percentage of people in our home county finished college, even now, and that was even a smaller percentage in the 1970's. But my parents expected us to go to college, and we had access to many books, which a lot of families did not. My mom was an art teacher in high school so we were also given art materials from the time we were little. We were very fortunate that way. Most of us were born pretty creative, and I think it was wonderful to grow up playing all the time with these creative siblings because we could make up games and imagine things together. I believe this early kind of play was instrumental to how we later developed as artists, Sam and Catherine and I. At least it was for me. Growing up in West Virginia was poor in some ways, but it was rich in imaginative activity, and it was rich in its proximity to the natural world.

JAMES: What kind of literature did you read growing up?

ANN: Oh . . . stories about being outside. Books about dogs! Old Yeller, Where the Red Fern Grows, Sounder, that kind of thing.7Fred Gipson, Old Yeller (New York: Harper & Bros., 1956). Wilson Rawls, Where the Red Fern Grows (New York: Laurel-Leaf Books, 1961). William Armstrong, Sounder (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 1969). It wasn't that common to get kids' books that were set in rural areas, most seemed to be set in cities, so if I got my hands on books with rural settings, they resonated more. Where the Lilies Bloom was important to me. It was set in Appalachia. My Side of the Mountain was another one I really liked.8Jean Craighead George, My Side of the Mountain (New York: Scholastic, 1959). Bill Cleaver and Vera Cleaver, Where The Lilies Bloom (New York: Harper Collins, 1969).

Cover of William H. Armstrong's Sounder (New York: Harper & Row, 1969). Cover illustrations by James Barkley.

JAMES: What kind of things would you write as a child?

ANN: When I began to write, I usually wouldn't finish things, but I would write the starts to disaster stories or adventure stories. I didn't understand what "literature" was or why you would read it, so as a teenager, I read authors like Stephen King. But by the time I was sixteen, along with the disaster stories and horror stories, I wrote a few pieces set in West Virginia, pieces that were realism and based on my own experiences. Even then, I knew that those stories felt different in my body.

JAMES: Living so close to the boundaries of other states, how did you identify as a West Virginian?

ANN: Growing up, many of us were very aware we were West Virginian. As a kid in West Virginia, you get a lot of messaging from the larger culture and from the states surrounding you that your place is more backwards, that you are hicks. And, of course, the media delivered that message all the time about "hillbillies." So I understood us as underdogs and I understood that others looked down on us. That sense of identity didn't come from my parents, it came more from the dominant culture. And anytime we ventured out of West Virginia (not that it was common) I was very aware of how West Virginia was different, and how people considered us lesser than them.

College and Travel

Nighttime shot of Woodburn Hall on the West Virginia University Campus, Morgantown, West Virginia, April 22, 2007. Photograph by Flickr user J. Robinson. Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

JAMES: Why did you decide to stay in West Virginia for college?

ANN: It was an economic thing. I didn't know how to get scholarships anywhere else, and my dad planned to pay for it, so he said we needed to go to school in state. I did get a good scholarship from WVU after my first semester.

JAMES: How was college? Was it strange being close to and yet apart from your family?

ANN: College was really difficult for me socially. I did fine academically, but going to Morgantown was a culture shock, even though it was only a hundred miles from Romney. Now I know a small college would have been much better for me. I don't know what WVU is like now, but at that time we had a large number of out of state students, partly because our tuition was so cheap, and the whole time I was there I only had one professor who was actually from Appalachia. I experienced a lot of culture clash at WVU and little sensitivity to that on the part of the faculty and the administration. I think it's different there now.

Morgantown, West Virginia Skyline, Morgantown, West Virginia, June 4, 2011. Photograph by Flickr user J. Stephen Conn. Creative Commons license CC BY-NC 2.0.

JAMES: In what ways did you experience this culture clash?

ANN: Our accents marked us. You'd open your mouth, and others would make assumptions about your intelligence and class and politics and your level of sophistication. It made you want to keep quiet. I think now about interviews Catherine and I did for her documentary, and how people in southern West Virginia would preface things by saying, "Now, I can't talk good," and then they'd say something incredibly insightful. In their accent.

JAMES: Early in Strange as this Weather Has Been you describe the loneliness of your protagonist Lace at West Virginia University in a way that feels intensely autobiographical.9"I told myself once I go to WVU, I'd never look back. Truth was, though, after a month away, I was feeling a kind of lonesomeness I'd never known there was…they had hills in Morgantown, but not backhome hills, and not the same feel backhome hills wrap you in. I'd never understood that before, had never even known the feeling was there." Pancake, Strange as this Weather has Been, 4.

ANN: Yeah it is very autobiographical. I mean, I stayed, I didn't quit, but yeah a lot of that is autobiographical.

JAMES: Lace ends up dropping out of West Virginia University to return to the mountains. Did you ever think about following that trajectory?

ANN: Oh yeah, I thought about dropping out, but again, the alternatives were worse. By that time in my life, I'd worked fast food and done line work and waited tables and worked in a grocery store—I realized that if I dropped out, those kinds of jobs would be my future.

Osaka Nightlife, Osaka, Japan, October 23, 2016. Photograph by Flickr user Pedro Szekely. Creative Commons license CC-BY-SA 2.0.

JAMES: After college you just split for Japan.

ANN: Yeah [laughs]

JAMES: Why?

ANN: I heard about a job there from a friend, heard that the owner of a language school in Japan was coming to campus to interview, and I interviewed, and I got it. I had never, ever thought about going to Japan. But I was working at Wendy's, after graduating with my BA in English, no teaching certificate. Unemployment in West Virginia was 12% then. It could have been anybody that showed up, from Norway or South Africa, I think I would have gone.

JAMES: In terms of teaching abroad, particularly teaching English as a foreign language, do you feel that process of thinking about the construction of language had an impact on your own writing?

ANN: Hmm . . . that's a really good question. I think what had an impact was less the actual teaching of English than being in cultures that weren't American and weren't Appalachian. By being in such a radically different culture, I recognized that Appalachia itself had its own distinct and interesting culture, and I started to understand how different our language was from Standard English. It's hard to describe how mind-expanding it was to go from West Virginia to Japan. I'd not even been on a commercial airplane. As an artist and a writer from West Virginia living in Japan, I would feel like I had eyes opening all over my head. Also the Japanese relationship to art and to perception . . . their attentiveness and receptiveness to beauty in the everyday was something they gave to me.10In an earlier interview with Robert Gipe for Appalachian Journal, Pancake cited the impact of the Japanese 'wabi sabi' aesthetic, noting its similarities with Appalachian culture—"an aesthetic that values the old and flawed and rusty." Robert Gipe and Ann Pancake, "Straddling Two Worlds," Appalachian Journal, 2011.

Language and Regional Dialect

ANN: When I first started writing about West Virginia, I wrote with dialect by default, more or less unconsciously, because I wasn't yet very aware that we spoke a dialect nor was I aware that our accent was as strong as it was. I became more aware of the dialect in my stories as I got older and left West Virginia. I write very intuitively. When I'm doing early drafts I hear the story in my head or I hear sounds in my head or the characters talking in my head, and if I'm writing about West Virginia, those voices and sounds naturally come as dialect. Over the decades I have come to think more consciously about the politics of dialect. Dialect in literature can be used in a demeaning way, to set aside the characters who use dialect as "less than" the writer, the reader, and the characters who don't use dialect. Or, one can use dialect in a culturally sensitive and less politically regressive way. I, of course, aim for the latter. I want to use dialect in ways that empower the people I write about and in ways that show how beautiful and inventive Appalachian language can be.

JAMES: It feels like there is a form of double movement here where, to teach English as a foreign language, you became very aware of your own dialect, and the pressure to mould your own patterns of language into a standardised form of English. How aware of that conflict were you?

US 50 Looking West, Romney, West Virginia, 1942. Photograph originally published as part of the Farm Security Administration, Office of War Information Collection in the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in public domain.

ANN: When I first left West Virginia and was teaching ESL and then attending graduate school, I felt compelled to use Standard English exclusively and to clean up my accent. Once in Japan when teaching kindergartners, I walked in a classroom after six months or so and said "Good morning, how are you?" And they came right back with, "Fahhhn, Thank you." And I was kind of horrified, that without my knowledge, I had taught these forty, five-year-old Japanese kids English with an Appalachian accent without knowing I was doing that. So certainly during my twenties and during graduate school I tried to mask or change my accent. I don't worry about that so much anymore, although I know when I'm not home, my accent is much diminished. But I'm lucky because I can go back and forth, speak without the accent and speak with it, whereas some of my siblings have lost their accent and can't get it back.

JAMES: Do you worry about losing your accent? How does your accent relate to your identification with West Virginia?"

ANN: I have worried about it. But I know now it's not going to be lost because I'm fifty-three and if I go home I can go right back into it. It's not as strong as when I was little, but it's still in there.

JAMES: And after Japan you returned to the States, and then went to teach in American Samoa?

"Welcome to American Samoa," Nu'Uuli, Eastern District, American Samoa, February 22, 2008. Photograph by Flickr user Ben Miller. Creative Commons license CC BY-ND 2.0.

ANN: Yes, after Japan, I lived in Albuquerque, New Mexico for a year. After that, I taught in American Samoa. This was again economic necessity and also a desire for adventure.

JAMES: Did living in American Samoa affect the way you felt about yourself as an American?

ANN: That's a good question. In American Samoa, I lived for the first time in a place that had been colonized by the United States. I became acutely aware of colonization in the South Pacific and also more aware of the relationship between the US and other countries, the way America exerts power over other countries and exploits them.

JAMES: Did you see similarities or connections between class inequalities or exploitation in West Virginia, and American Samoa as part of a larger colonial project?

ANN: I did, I did. The connections became even more clear to me when I started living in parts of the US that weren't Appalachia, and as I began to understand dominant middle class white culture in the US. As I came to recognize the class discrepancies within the US and realized how little economic and political power Appalachia had, I saw the relationship between Appalachia and exploited non-Western countries. I realized how Appalachia can be seen as a resource colony for the larger United States. And those connections became more defined during graduate school when I started to read postcolonial theory and post-Marxist theory. The only places I've seen people as poor as they are in parts of southern West Virginia was in Indonesia and Thailand.

Samoan author Albert Wendt (right) with Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o (left), University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, Hawaii, April 30, 2008. Photograph by Flickr user Kanaka Rastamon. Creative Commons license CC BY-NC 2.0.

JAMES: Did that experience impact your direction in graduate school?

ANN: Yes. I wrote my master's thesis on a Samoan writer, Albert Wendt, using postcolonial theory. The driving question of my PhD dissertation was how Americans sustain their delusion that we have essentially a classless society given the glaring economic disparity in this country. I explored that question through nineteenth and twentieth-century literature and film. When Americans can't blame class discrepancy on racism, they often explain poverty as temporary. The idea is that the lower classes will eventually catch up, in time. This has been used to explain the "Appalachian problem," when Appalachia's poverty is not attributed to how dumb and lazy we are.

JAMES: Alongside your dissertation were you still writing fiction?

ANN: I was writing fiction whenever I could. That usually meant during breaks between quarters. While I was writing so much intellect-driven scholarly work, the pressure to write intuitive fiction would build, so when I had a break, the fiction would kind of come boiling out.

Early Work and Literary Style

Cover of Ann Pancake's Given Ground (Hanover, NH, Middlebury College Press, University Press of New England, 2001).

JAMES: Your first published collection Given Ground was released not too long after you finished graduate school. Was that writing you had been collecting and publishing over a period of time?

ANN: Yes. The oldest story in that book, "Getting Wood," I wrote in 1987. Those stories were not written as a collection but pulled together over a period of years.

JAMES: How did you pick the stories you wanted to put into the collection?

ANN: I pulled together Given Ground when I needed to publish a book for tenure. I put into it every story I'd written that seemed finished enough, and then received feedback from a few friends. I jettisoned one story, then wrote "Redneck Boys" to complete the book. Half of the stories had been published in literary journals already, so that was a kind of confirmation that they were solid enough to put into the collection. However, if I hadn't had the pressure of tenure, I wouldn't have tried to publish that book because I didn't think it was strong enough to find a publisher. Not yet.

JAMES: Did the reaction to the book surprise you? Or is critical acclaim not something you really put a lot of weight on?

ANN: The award, the Bakeless Prize, was a huge surprise. And I was surprised, too, by how the book has been received. It's not an easy book in a lot of ways. The sensibility and style are idiosyncratic, I think. The subject matter is dark. I've come to understand that it's not ever going to reach a broad audience, but those readers it does reach, it reaches deeply, and that's fine with me.

JAMES: To what extent can that idiosyncrasy be traced back to West Virginia? Or, to your broader nomadic experience as a young adult?

ANN: The idiosyncrasy in my writing is mostly rooted in having grown up in WV, although I may not have recognized those idiosyncratic parts without the perspective of having lived in wildly different cultures outside West Virginia. But part of the idiosyncrasy I think I was just born with.

JAMES: You've been praised for moving away from a literary tradition rooted in formula and caricature, and for the complexity of your characterisation of both Appalachia's land and people. Was that always explicit in your work?

ANN: I was aware that I was resisting stereotype by the time I was writing in college. There are plenty of amazing Appalachian writers who work with complex representations of our region and who influenced me. Still, much writing about Appalachia over the past 150 years, especially writing that has gotten wide distribution, has been by outsiders, and a lot of that perpetuates the usual stereotypes. I've come to believe that the general reading public expects those stereotypes, so publishers expect them, too. But what I also understand are the political ramifications of stereotypes—they demean the people, make it easier to justify their exploitation, easier to see them as worthless. So I've always been very sensitive about complicating or overturning the usual caricatures and stereotypes.

JAMES: Could you name some of those writers, and say how their work appeals to you and what makes it unique?

Jayne Anne Phillips (seated on far right) featured on a panel with (from left to right) Kaylie Jones, Marlon James, and Elizabeth Nunez at the Brooklyn Book Festival, Brooklyn, New York, September 12, 2010. Photograph by Flickr user Navdeep Dhillon. Creative Commons license CC BY 2.0.

ANN: Some writers from West Virginia who work with complex representations of the region and who influenced me as a younger writer include Breece Pancake, Jayne Anne Phillips, Denise Giardina, Davis Grubb, and Chuck Kinder.11Breece Pancake, The Stories of Breece D'J Pancake (Boston, MA: Little, Brown,1983). Jayne Anne Phillips, Black Tickets (New York: Dell Pub., 1979). Jayne Anne Phillips, Machine Dreams (New York: E.P. Dutton/Seymour Lawrence, 1984). Jayne Anne Phillips, Lark and Termite: A Novel (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009). Denise Giardina, The Unquiet Earth: A Novel (New York: Norton, 1992). Denise Giardina, Storming Heaven: A Novel (New York: Ballantine Pub. Group, 1987). Davis Grubb, The Night of the Hunter (New York: Harper, 1953). Davis Grubb, The Voices Of Glory (New York: Scribner, 1962). Chuck Kinder, Snakehunter (New York: Knopf, 1973).All of these writers grew up in West Virginia. Each has a different vision of the place, but each vision presents our culture with a nuanced depth perception that complicates the one-note picture of Appalachia so often perpetuated by outsider writers. They offer characters struggling with internal contradictions; they provide context and history that help shed light on the state's darker elements; they carry a sense of place deep in their bodies; and they do amazing things with our language.

There are also West Virginia writers younger than I am who deserve far more recognition than they've received so far, writers who are writing better, in my opinion, than most of their peers outside the region: Jessie Van Eerden; Matthew Neil Null; Glenn Taylor. Only Glenn has received much notice from the wider literary establishment.12For recent work see Jessie Van Eerden, My Radio Radio (Morgantown, WV: Vandalia Press, 2016). Matthew Neill Null, Honey from the Lion (Wilmington, NC: Lookout Books, 2015). M. Glenn Taylor, A Hanging at Cinder Bottom (London Borough Press, 2015).

JAMES: The way you write about Appalachia is clearly very striking, but also something which can be co-opted into broader cultural/media narratives of Appalachian rural poverty that offer a simplistic and frequently unflattering image of Appalachian life—do you grapple with this as a writer, how aware of it are you, does it affect your craft or editing process?

ANN: I'm very aware of how easily one can lapse into stereotype when writing about Appalachia. Appalachian people in the world are confronted with stereotypes about themselves constantly, so we're sharply conscious of them. Still, in early drafts, I might fall into a stereotype because I haven't gotten to the stage of the work where I'm complicating things. So, to answer your question, when I'm writing about violence in Appalachia, I try to be careful to complicate the issue. I try to tell the truth, and I try to tell it with context and by offering different perspectives on the violence and by making the perpetrators and the victims full human beings as opposed to flat caricatures.

West Virginia is its own culture within Appalachian culture, and Appalachian culture, in turn, shares some qualities with US southern culture. If I'm around Southerners there is a feeling of familiarity and home, more so than if I'm around people from Pennsylvania, even though Pennsylvania is fifty miles from where I grew up. I've also been influenced as a writer primarily by writers from the South and from Appalachia.

Map of county secession votes of 1860–1861 in Appalachia. Map drawn by E. Hergesheimer. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Creative Commons license CC BY-SA 4.0.

JAMES: I wanted to talk a little about your use of violence in your writing. One of the recurrent themes in your work is ghosts, especially in relation to the Confederacy and the Civil War. How does that historical violence, or its afterlife, translate into and overlap with physical or literal violence?

ANN: That's a good observation and a good question. I'm not sure how exactly to answer it. Appalachia does have a violent past: the violence of the Civil War and the "Indian" wars before that; the violence inflicted on the environment starting from the time of industrialization; the violence surrounding the labor movement in the early part of the twentieth century; the forms of violence the larger nation imposes on Appalachia in its appetite for Appalachian resources. Appalachian people are not more violent than other Americans, however, despite popular narratives to the contrary. In fact, before the drug epidemic, West Virginia consistently had the lowest violent crime rate in the nation. Still, I believe that all that violence in our past continues to manifest in our present.

The violence to the environment continues, and there is not the political will to stop it, and there is much violence suffered by Appalachia's people. Although often that's self-inflicted: addiction, overdose, suicide. I believe that self-inflicted violence is related to environmental destruction and economic exploitation. I recognize that my work contains a fair amount of literal violence. Some of that is just factual, reflecting the region's history. Some of the violence in my work, though, probably comes out of my love and hate for the region, my fears of and for the region, and my deep desires for the region. The violence may arise from all that conflicted unconscious material.

"Early Memorial" and "Stonewall Jackson," Interpretive Signage, Romney, West Virginia, November 13, 2011. Photograph by Flickr user Ron Cogswell. Creative Commons license CC BY 2.0.

JAMES: How much of that fear comes from a sense of displacement, or fracture? Earlier you talked about becoming aware of your identity as a West Virginian through interacting with people from surrounding states. You describe a sense of "we are this because we are not something else." How much of that can be traced back to the Civil War?

ANN: West Virginia's paradoxical place in the Civil War is one of the reasons I find West Virginia fascinating. The state separated from Virginia to be part of the Union in 1863, and popular belief is that we did this because we were against slavery. The truth about our secession is much more complicated and is tied also to the schemes of industrialists. There were certainly Union sympathizers in West Virginia and Union troops. My county, Hampshire, was very Confederate, though, with slave-owners, including my own family. Romney was right on the border, and Romney changed hands between the Union and the Confederacy fifty-four times during the war. I grew up playing in Civil War trenches a mile behind my house.13The trenches Pancake is describing are the Fort Mill Ridge Civil War Trenches, among the best preserved Civil War trenches in the nation. "Fort Mill Civil War Trenches", National Parks Service, http://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/places/13001121.htm.The remnants of the war were very present when I was growing up. And there are stories my family has passed down from the war—my family was Confederate identified, so their stories are about the Yankees coming in and raiding the farm.

JAMES: That feeds into another question I wanted to ask about the role of race in your work—I believe West Virginia is the third or fourth whitest state in the country.14According to the latest United States Census estimates, West Virginia is the fourth-whitest state in the Union.

ANN: West Virginia is very white, but there are and were African-Americans there. It's true, they don't often appear in my work, and I don't think I have any who are main characters. I believe this is the case because I don't want to misappropriate or misrepresent them. My personal relationship with race growing up taught me a lot. My county was very racist and still is, but my parents were much more liberal than most people there. My parents tried to bring us up with a "colorblind" philosophy: everyone is the same regardless of skin color, which also of course isn't true, but it was pretty enlightened for those times and that place. In junior high and high school I had an African-American boyfriend. I haven't talked about that or written about it much, I probably should. That certainly opened my eyes to racism, by the time I was fourteen, because of the kinds of insults I would receive and also because I started to see through my boyfriend's perspective. It also called into question my belief in Christianity. I started to reject the church at that time in large part because I saw very clearly its hypocrisy concerning race, at least where I lived.

JAMES: In your work you're very aware of trying to offer a representative account of West Virginian life. Are you more reluctant to write about African American experience?

ANN: Yeah, I'm much more comfortable writing about class. It's good that you bring that up, people don't usually ask me about it. The truth is, I do have experience with race in Appalachia. I need to ask myself why I don't write more about it.

JAMES: I want to read a short moment from your short story "Ghostless" which encapsulates one of the reasons I enjoy your writing so much:

The cold came high in my chest, but the wind had finally laid and from some distance I could feel the heat off the horse. The hide-odor off the horse, that soily smell he carried even in winter. I pushed my face into it, into the hollow behind the shoulder, before the belly swell . . . . I still had horse on my hands, and I smeared them across my Sunday pants, listening, the wood fire brightening my back.

That's gorgeous. The physicality of your writing, its tactile nature, your relationship to senses and sensory language. Where does that come from and how has it developed over time?

ANN: I write by sinking myself as deeply as I can into a place or a person, then imagining how the character's senses would respond to a situation, or imagining how I personally would react sensorily to a place. Certainly touch and smell in particular are powerful for me in the way they evoke memories. The way they are more animal. I also revise a whole lot, so as I do more drafting, more of that sensory detail comes in.

Me Up the Hollow, Romney, West Virginia, December 14, year unknown. Photograph by Ann Pancake. Courtesy of Ann Pancake.

JAMES: And growing up in West Virginia played an important role in developing that detail in your work?

ANN: Now that I've lived out of West Virginia I've come to understand that growing up in Appalachia usually means growing up closer to the ground than one might in other places. Growing up in Appalachia in the 70's was pretty raw. You were not sheltered in the ways the middle-class is sheltered in Seattle. We had a lot of tactile interaction with the natural world, plants and animals, we were raised working big gardens and running the woods, and we saw our food get killed and skinned out and butchered. We ate that. I think as little kids we were very directly in touch with our senses. We weren't inside, we weren't on computers. I could also identify how poor people were by how they smelled, because the really poor people didn't have plumbing, so couldn't wash like we could. I see this as a metaphor for how white poverty is sometimes invisible in this country.

JAMES: How do you keep that visceral relationship to West Virginia in your writing?

ANN: I try to get home at least twice a year, and the place is very deeply embedded in my memory and in my body, so it's present to some extent even when I'm not there. When I do return, I can settle back into the land pretty quickly. At the same time, the culture in West Virginia has changed since I was a kid. Also, at this point in my life and my career, I'd like to be writing more about places that aren't West Virginia. That'll happen some in my next book.

Presents, Pasts, and Futures

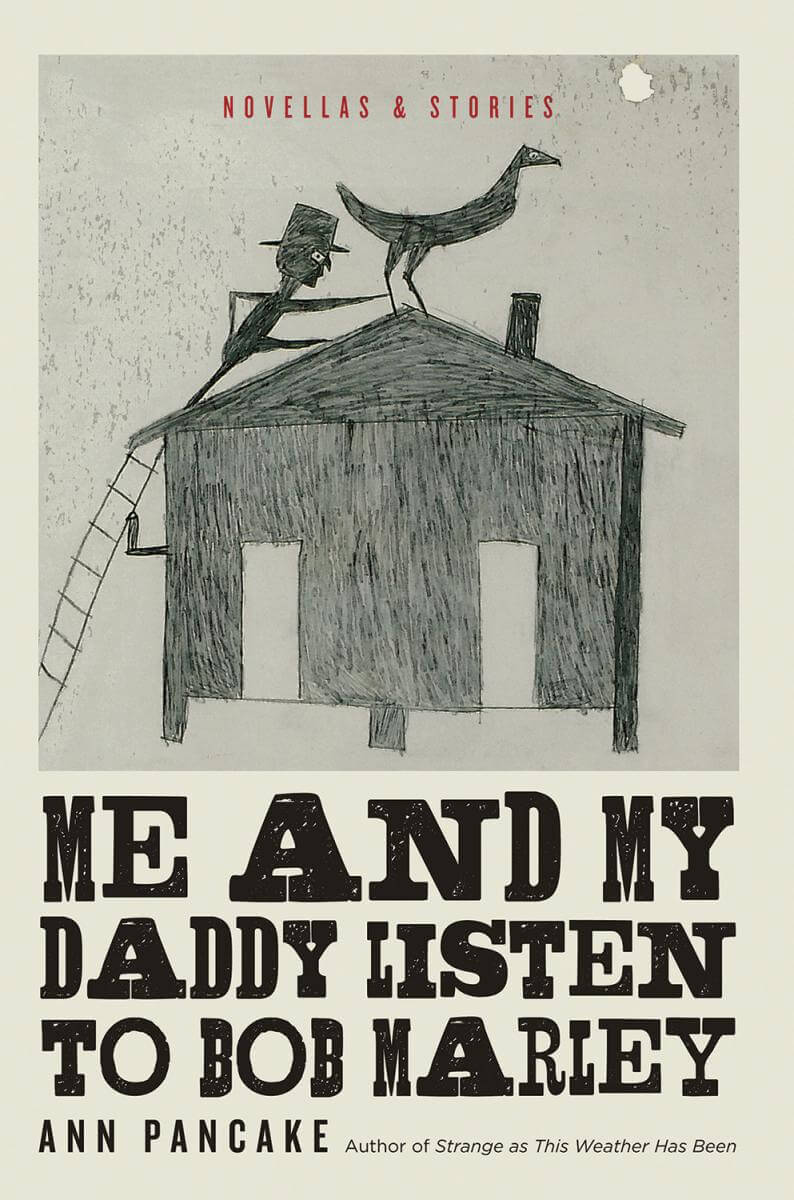

Cover of Ann Pancake's Me and My Daddy Listen to Bob Marley (Berkeley: Counterpoint Press/Shoemaker & Hoard, 2015). Cover design by Briar Levit.

JAMES: Your latest collection Me and My Daddy Listen to Bob Marley remains centered in West Virginia, but in a different way. There seems to be more scope for hope or forward momentum than in your earlier writing.

ANN: I'd agree with that, I think part of it is time of life. I'm at a point in my life where I just can't bear to be spending all that time in darkness like I could while writing Given Ground and some of my earlier work. I also think that, just in order to survive as an American in 2016, I've had to try to figure out ways to look towards light exactly because we are in such a dark time, from a certain perspective. I also think—I wrote about this in an essay for the Georgia Review—I'm finished with writing about how things are hurt in Appalachia.15Ann Pancake, "Towards Light," Georgia Review, 2009. I'm tired of documenting destruction. I'm committed to writing that imagines unconventional ways to relate to the natural, including the natural world in Appalachia. Some of the stories in Me and My Daddy Listen to Bob Marley such as "Sab" or "The Following" play with redefining relationship with the natural world.

JAMES: In the story that opens Me and My Daddy, "In Such Light," that progression definitely comes through. Trauma and hurt persist, but it holds more scope for maturation than many of your earlier stories.

ANN: I'd agree.

JAMES: Do you think that literary shift is connected to a broader recognition within the United States that the country needs to move away from a reliance on coal and seek less destructive and more sustainable forms of energy?

Dragline, West Virginia, ca. 2007. Photograph by Vivian Stockman. Courtesy of Ann Pancake.

ANN: I think my literary shift is connected to a recognition that we won't survive as a species unless we think very, very differently about live beings that aren't human in this world. As for the shift away from coal, it is true that in Appalachia less coal is being mined now, but that's in part because of the boom in natural gas. Areas of West Virginia that were untouched by coal mining are now being devastated by hydrofracking. However, I do think we're at the beginning of the end of coal. And I think there is a wider movement, particular among younger generations in West Virginia, which understands that our state must move beyond dependence on natural resource extraction if we are to survive as a culture and as a people. This gives me optimism.

JAMES: It's been almost fifteen years since the publication of your first short story collection. What do you think are the most notable differences between Me and My Daddy and Given Ground?

ANN: Given Ground was written almost entirely intuitively and without much consideration of an audience. I wrote that book mostly for myself, not because I'm a narcissist, but because I couldn't imagine that many people would want to read those stories. For those reasons, it's more music-driven, less concerned with plot, and less accessible than Me and My Daddy. Me and My Daddy I obviously wrote after finishing my novel, and the novel required that I learn how to work with plot and that I make my writing more accessible. I wanted an audience for Strange as this Weather Has Been. I think those influences and considerations bled over into my writing of Me and My Daddy. Teaching creative writing and writing a novel has made me more conscious of craft, has made me use a little more intellect when I write fiction. I'm not convinced, however, that that is a good thing.

JAMES: Why did you choose that particular title?

ANN: [Laughs] My publisher decided that. I had named the book "Bone Dowser" which was also the original name of the story in the collection now called "The Following." My publisher thought we'd sell more books with the title Me and My Daddy Listen to Bob Marley. I'm sure he's right.

JAMES: If that was a conversation which had happened fifteen years ago, do you think the outcome would have been the same?

ANN: [Laughs] would I have been as malleable do you mean? No I probably would have been more resistant. I've become less resistant, and I don't have as much investment in that kind of stuff anymore. That's a good question!

JAMES: Part of maturing is coming to terms with what exactly you are able to do through your work and through your activism, and being able to channel that in ways and into things which are productive.

ANN: Yeah, exactly.

Breakneck Scenic Overlook, Romney, West Virginia, July 29, 2014. Photograph by Justin Wilcox. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Creative Commons license CC BY-SA 4.0. Pancake family land appears in the lower section of the photo.

JAMES: Do you ever feel like you're writing about a West Virginia that doesn't exist in the same way anymore?

ANN: In some ways West Virginia has changed significantly since I grew up there. One change that I mourn is the way the dialect and accent are being lost among younger people. Exposure to mass media is homogenizing our language. The place is also under greater environmental attack and is suffering a drug addiction epidemic. Those changes, though, I understand very well, because of my research and experiences and because of addiction problems in my family, so when I write about that West Virginia, I'm writing about one that still exists.

JAMES: You live in Seattle now, quite far removed from Appalachia. Is your relationship with the land different now, and if so in what ways?

Seattle Skyline view from Queen Anne Hill, Seattle, Washington, February 17, 2010. Photograph by Wikimedia Commons user Daniel Schwen. Creative Commons license CC BY-SA 4.0.

ANN: I'm not immersed in the land here like I was growing up in West Virginia. Also, the land here doesn't speak to me like back home does. It doesn't give me sounds and stories. Still, I love the mountains in Washington. But it feels more like a friend, while back home land feels like family -- and that includes the way family can be fraught. My relationship to the land back home is very painful because there is so much ongoing destruction of it. In Washington, there is certainly destruction, but because of the kind of economic and political will here, there are vast tracts of land that aren't going to be destroyed, at least not anytime soon, and I can escape into those. That helps to ameliorate the pain I feel about back home. But I won't ever be rooted in the land in Washington like I am rooted in Appalachia.

JAMES: What's the next step? You mentioned that moving forward you are looking to write about Appalachia, but in different ways, and then looking to write about other things as well.

ANN: I can't be really specific about the project I'm working on now because it's in its very early stages, but it's a book that explores the ways we can have different relationships with the natural world and with things that aren't human. It's nonfiction. So there's that strand of it, which runs simultaneously with the ways I see Appalachia as a microcosm of what's happening globally in terms of the environment and as a harbinger of where we're headed without a revolution in our common sense. Finally, there' s a thread about my family, whom I see as a kind of microcosm of Appalachia, in the ways my family's addiction, fear, economic exigencies, and mental illness have caused the destruction of land I love where I grew up.

The book is part memoir, part imagining forward. It asks how we might live well in a time of mass extinction. A modest thesis, I know. I'm obsessed with the question because I've witnessed all my life a place I love be destroyed. Appalachia has always been called backwards, but in the last couple of decades, the rest of the country caught up with Appalachia and recognized the natural environment everywhere is being devastated.

Appalachia Forest Action Project volunteers learning about the land, Rock Creek, West Virginia, May 21, 1994. Photograph by Mary Hufford. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress American Folklife Center.

Most recently, the land where I grew up, in Romney, has been destroyed by the parts of my family who are entangled in my brother's drug addiction. I see this family dynamic and tragedy as a microcosm of larger destructive forces in Appalachia. I see Appalachia, in turn, as a microcosm of larger destructive forces in the United States, especially capitalist corporate forces. So in this new book, I plumb that question—"how do we live well while natural places and beings are being annihilated at an unprecedented rate?"—by tracing my own personal history of loss as a West Virginian.

Part of my answer to the question involves radically reconceiving our relationships with natural beings. To do that, we need to become intellectually flexible enough to see rationalism and mechanistic science as just one way of knowing among several, with no one way superior to the other, and each with its own purpose. In other words, I'm suggesting we give more validity to intuition, the unconscious mind, the imagination, and ideas of the sacred.

About the Interviewer

E. James West is a teaching fellow in the Department of History at the University of Birmingham and a postdoctoral fellow at the Eccles Centre for American Studies at the British Library. His research centers upon on African American history and literature since 1865, with a particular interest in African American media and print culture.

Cover Image Attribution:

Cover of Ann Pancake’s Strange as this Weather Has Been (Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint Press/Shoemaker & Horn, 2007). Cover features Jeff Chapman-Crane's mixed-media sculpture The Agony of Gaia.Recommended Resources

Text

Bell, Shannon Elizabeth. Our Roots Run Deep as Ironweed: Appalachian Women and the Fight for Environmental Justice. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Lanier, Parks, ed. The Poetics of Appalachian Space. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1991.

Lewis, Ronald L. and John C. Hennen, Jr. West Virginia History: Critical Essays on the Literature. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company, 1993.

Pancake, Ann. Given Ground. Middlebury, VT: Middlebury College Press, 2001.

———. Me and My Daddy Listen to Bob Marley. Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint Press/Shoemaker & Hoard, 2016.

———. Strange as this Weather Has Been. Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint Press/Shoemaker & Hoard Publishers, 2007.

Smith, Barbara Ellen, Stephen Fisher, Phillip Obermiller, David Whisnant, Emily Satterwhite, and Rodger Cunningham. "Appalachian Identity: A Roundtable Discussion." Appalachian Journal 38, no. 1 (2010): 56–76.

Web

"About Black Diamonds." Black Diamonds: Mountaintop Removal & the Fight for Coalfield Justice. 2007. http://www.blackdiamondsmovie.com/aboutblackdiamonds.html.

"Communities at Risk from Mountaintop Removal." Appalachian Voices. April 2015. http://appvoices.org/end-mountaintop-removal/communities-at-risk/.

Pancake, Ann. "Ann Pancake's Reading List." Orion Magazine. Accessed April 4, 2017. https://orionmagazine.org/article/ann-pancakes-reading-list/.

Ward, Ken. "National Academy of Sciences to Study Mountaintop Removal Health Effects." Charleston Gazette-Mail. August 3, 2016. http://www.wvgazettemail.com/news/20160803/national-academy-of-sciences-to-study-mountaintop-removal-health-effects.

"West Virginia." Looking at Appalachia. Accessed April 4, 2017. http://lookingatappalachia.org/west-virginia.

West Virginia Division of Culture and History. "Online Exhibits." West Virginia Archives and History. Accessed April 4, 2017. http://www.wvculture.org/museum/exhibitsonline.html.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Elizabeth Judd, "Books in Brief," New York Times, August 12, 2001. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Ann Pancake, Strange as this Weather Has Been (Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint Press/ Shoemaker & Hoard, 2007). |

| 3. | Jeremy Jones, "Ann Pancake's STRANGE AS THIS WEATHER HAS BEEN," Iowa Review, January 8, 2011. |

| 4. | "Me and My Daddy Listen to Bob Marley," Publisher's Weekly, December 8, 2014. |

| 5. | Quotes taken from Pancake's personal website, http://www.annpancake.blogspot.com. |

| 6. | Sam Pancake and Catherine Pancake. Ann and Catherine collaborated on the production of Black Diamonds, a 2006 documentary film about mountaintop removal and the fight for coalfield justice in West Virginia. |

| 7. | Fred Gipson, Old Yeller (New York: Harper & Bros., 1956). Wilson Rawls, Where the Red Fern Grows (New York: Laurel-Leaf Books, 1961). William Armstrong, Sounder (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 1969). |

| 8. | Jean Craighead George, My Side of the Mountain (New York: Scholastic, 1959). Bill Cleaver and Vera Cleaver, Where The Lilies Bloom (New York: Harper Collins, 1969). |

| 9. | "I told myself once I go to WVU, I'd never look back. Truth was, though, after a month away, I was feeling a kind of lonesomeness I'd never known there was…they had hills in Morgantown, but not backhome hills, and not the same feel backhome hills wrap you in. I'd never understood that before, had never even known the feeling was there." Pancake, Strange as this Weather has Been, 4. |

| 10. | In an earlier interview with Robert Gipe for Appalachian Journal, Pancake cited the impact of the Japanese 'wabi sabi' aesthetic, noting its similarities with Appalachian culture—"an aesthetic that values the old and flawed and rusty." Robert Gipe and Ann Pancake, "Straddling Two Worlds," Appalachian Journal, 2011. |

| 11. | Breece Pancake, The Stories of Breece D'J Pancake (Boston, MA: Little, Brown,1983). Jayne Anne Phillips, Black Tickets (New York: Dell Pub., 1979). Jayne Anne Phillips, Machine Dreams (New York: E.P. Dutton/Seymour Lawrence, 1984). Jayne Anne Phillips, Lark and Termite: A Novel (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009). Denise Giardina, The Unquiet Earth: A Novel (New York: Norton, 1992). Denise Giardina, Storming Heaven: A Novel (New York: Ballantine Pub. Group, 1987). Davis Grubb, The Night of the Hunter (New York: Harper, 1953). Davis Grubb, The Voices Of Glory (New York: Scribner, 1962). Chuck Kinder, Snakehunter (New York: Knopf, 1973). |

| 12. | For recent work see Jessie Van Eerden, My Radio Radio (Morgantown, WV: Vandalia Press, 2016). Matthew Neill Null, Honey from the Lion (Wilmington, NC: Lookout Books, 2015). M. Glenn Taylor, A Hanging at Cinder Bottom (London Borough Press, 2015). |

| 13. | The trenches Pancake is describing are the Fort Mill Ridge Civil War Trenches, among the best preserved Civil War trenches in the nation. "Fort Mill Civil War Trenches", National Parks Service, http://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/places/13001121.htm. |

| 14. | According to the latest United States Census estimates, West Virginia is the fourth-whitest state in the Union. |

| 15. | Ann Pancake, "Towards Light," Georgia Review, 2009. |