Overview

The 1838 expulsion of the Cherokee Nation from the state of Georgia culminated a decade of oppressive policies and more than two decades of federal pressure on Native Americans to give up their homelands to white settlement. The expulsion occurred over six weeks under the supervision of soldiers stationed at fourteen sites in north Georgia. Evidence from each site documents the individual and institutional abuse spawned by the state’s policies, locates the sources of white citizen aggression, and remembers the Cherokees who navigated the treacherous road of removal. Sarah Hill examines the historic violence against a minority population and culture in this essay about Cherokee expulsion from Rome, Georgia.

Georgia, 1831. Map by Young & Delleker, Sc. Published by A. Finley. Courtesy of the Historic Maps collection, Georgia Archives, University System of Georgia.

Georgia led the United States in the expulsion of the Cherokee Nation from its homeland. In the spring of 1838 more than two thousand soldiers arrested some nine thousand Georgia Cherokees, confined them briefly, then marched them to holding camps in east Tennessee to await their miserable trek to Indian Territory eight hundred miles away. Removed from Georgia in June, the last detachment of Cherokees left the Tennessee camps in November. Images of grieving Natives stumbling westward seized the popular imagination, throwing into shadow the record of how, why, when, and where the expulsion began. In succeeding years, the emphasis on suffering reduced the Cherokees to anonymous victims and obscured the activities of those who enabled and enforced their expulsion. The missing accounts of Cherokee removal emerge most vividly in the stories of each removal site. As the home of the Cherokee Nation's most prominent leaders and the location of two military removal stations, Rome, Georgia has much to teach.

Measuring Chains and Axes

Detail of "Doodle" Plat showing a drawing of land surveyors, from a plat of Georgia land granted to William Few, ca. 1784. Courtesy of the Ad Hoc collection, Georgia Archives, University System of Georgia.

An early history of Rome1George Magruder Battey, Jr., A History of Rome and Floyd County, State of Georgia, United States, Including Numerous Incidents of More Than Local Interest, 1540–1922 (Atlanta, GA: The Webb and Vary Co., 1922), 33–4; Jerry R. Desmond, Georgia's Rome: A Brief History (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2008), 28–30. Author of the popular history of the city and county, Battey was the son-in-law of founder William Smith. On Dec. 21, 1833, the Georgia General Assembly incorporated Livingston as a town and designated it the county seat of recently-formed Floyd County: Acts of the General Assembly of the State of Georgia, 1833 (Milledgeville: Polhill and Fort, 1834), 321–22 (hereafter Ga. Acts). describes the city's founding as an inspiration that sprang from the chance encounter of enterprising lawyers with a gracious planter. According to the idyll, attorneys Colonel Daniel Randolph Mitchell and Colonel Zachariah Branscomb Hargrove were traveling by horseback in the spring of 1834 to the Floyd County courthouse in Livingston. The men "hauled up at a small spring" and dismounted to slake their thirst. As they relaxed under a willow tree, they gazed across the small peninsula lying at the convergence of two rivers. On one side of the peninsula, the Etowah River meandered eastward more than one hundred sixty miles to merge with the Oostanaula River that ran some fifty miles from the north and east. The two waterways joined at the peninsula's tip to form the Coosa River that flowed west into the Alabama River and marked the western boundary of Georgia.

Eyeing the landscape, Hargrove exclaimed, "This would make a splendid site for a town!" An approaching stranger, Major Philip Walker Hemphill, overheard Hargrove and joined in agreement, "having been convinced for some time" the site offered "exceptional opportunities for building the largest and most prosperous" city in the region. Continuing their conversation, the three journeyed some two miles south along the Cave Spring Road to Hemphill's "comfortable plantation home," the Alhambra, and began planning a city. The major's cousin, General James Hemphill, was entering the legislature the next session and could be relied on to relocate the county seat from Livingston to the proposed site. After including Colonel William Thornton Smith in their initiative, the foursome would need to acquire "all available land" and procure rights to the ferries essential for crossing the three rivers. Smith agreed to join the coalition and the four men signed "a contract along these lines" in the Floyd County Inferior Court. They left details to their friend, attorney John H. Lumpkin, who had recently resigned as secretary to his uncle, Governor Wilson Lumpkin.2Battey, History of Rome, 33–4. The rest, some say, is history. But it is not the whole story.

Top, John Ross, A Cherokee Chief, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1843. Hand-colored lithograph on paper by Alfred M. Hoffy. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Middle, Major Ridge, a Cherokee Chief, Washington, D.C., 1838. Hand-colored lithograph by John T. Bowen. Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.24339. Bottom, John Ridge (ca. 1802 – June 22, 1839), 1825. Portrait by Charles Bird King. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in public domain.

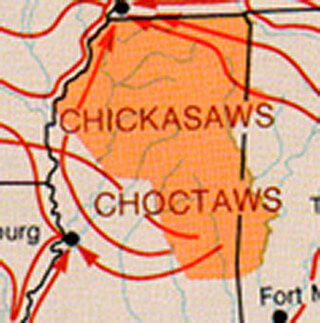

Other histories course beneath the soothing narrative of Rome's founding. When the visionaries began planning, some nine hundred Cherokees lived along the Etowah, Oostanaula, and Coosa Rivers and tributaries, including Principal Chief John Ross and Cherokee Nation leaders Major Ridge and his son, John. The site chosen for the city was the heart of the Cherokee Nation that had been gradually reduced to contiguous portions of four southeastern states. Events in Georgia portended even greater change. Between 1830 and 1838, Cherokees struggled to retain their homes, farms, and freedom while Georgia, followed by other states, asserted sovereignty over them and claimed rights to their land. In December 1831, the state legislature identified the Cherokee Nation in Georgia as Cherokee County. A bill the following year subdivided Cherokee County into nine additional counties. Approximately five hundred square miles of land bordering Alabama was designated as Floyd County in honor of Creek Indian fighter and state militia commander General John Floyd. Determined to force the federal government to fulfill its unique agreement to eliminate Indian land title, Georgia authorized a survey of Cherokee land within the state's purported boundaries and ordered a lottery for its distribution. On May 24, 1832, John Harvey completed his survey of Floyd County, having marked the property of all resident Cherokees including John Ross, Major Ridge, and John Ridge.3Ga. Acts, Dec. 26, 1831 (Milledgeville, GA: Prince and Ragland, 1832), 74–6. The state added portions of Habersham and Hall counties, which had been acquired from the Cherokees in the Treaties of 1817 and 1819, to Cherokee County and then subdivided the entire area into nine additional counties: Historical Atlas of Georgia Counties, http://georgiainfo.galileo.usg.edu/histcountymaps/index.htm; Ga. Acts, Dec. 3, 1832, http://neptune3.galib.uga.edu; Daniel Haskel and J. Calvin Smith, A Complete Descriptive and Statistical Gazetteer of the United States of America (New Haven: Hitchcock and Stafford, 1843), 216; Ga. Acts, Dec. 21, 1830 (Milledgeville: Camak and Ragland, 1830), 127–145; Field Notebooks, Survey Records, Cherokee County, Georgia Surveyor General, RG 3-3-3, Georgia Archives, Morrow, GA.

While surveyors such as Harvey carted measuring chains and axes across the farms and fields of the Cherokees, Georgians registered for the October lotteries that would distribute their land to so-called fortunate drawers. Anticipation ran high. Georgia was the only state in the nation that dispensed Native land by public lottery. The purpose of the policy was to attract white settlement, avoid concentrations of land-based wealth, and provide credibility to the legislators who wrote the land laws.4The legislature introduced the lottery system following the infamous Yazoo frauds of the 1780s and 90s in which General Assembly members sold millions of acres of Georgia's western lands to speculating companies. The 1795 sale included bribes to legislators, state officials, and other prominent Georgians. See C. Peter Magrath, Yazoo: Law and Politics in the New Republic (Providence, RI: Brown University Press, 1966); George R. Lamplugh, "Yazoo Land Fraud," New Georgia Encyclopedia, Sept. 14, 2015. Inevitably, the procedure spurred white resentment toward Native Americans who resisted appropriation of their land and toward the federal government that was supposed to protect and negotiate with Indians. Between 1805 and 1827, the state held five lotteries to give away land that had belonged to the Muscogee Creek Indians. After the Creeks were expelled from the state in 1826, Cherokees remained the only obstacle to Georgia's expansion. Their lands were the last that would be offered in the state's public lotteries.

A map of that part of Georgia occupied by the Cherokee Indians, 1831. Map by John Bethune. Courtesy of Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, lccn.loc.gov/2004633028.

Georgia Lotteries and Native Lands

Responding to dwindling opportunities, 85,000 white Georgians registered for the first of two Cherokee lotteries held in 1832. When the lottery drums stopped turning, more than eighteen thousand land parcels of 160 acres each had been awarded to fortunate drawers.5Among the winners were Philip W. Hemphill, then of Jackson County, who won a lot on the Oostanaula River in what became Murray County, and William Smith, possibly the same as the fourth founder, who won a lot on the same river in the same county: James F. Smith, The Cherokee Land Lottery (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1838), 245, 257; Farris W. Cadle, Georgia Land Surveying History and Law (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1991), 278; Hoyt Bleakley and Joseph P. Ferrie, "Up From Poverty? The 1832 Cherokee Land Lottery and the Long-run Distribution of Wealth," National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 19175, June 2013, http://www.nber.org/papers/w19175. There were no gold lots in Floyd County. The second (and concomitant) lottery, which offered forty-acre parcels in the Cherokee gold belt, attracted 133,000 additional Georgians and dispensed 35,000 more land prizes. The numbers reveal a dimension of the challenge facing Cherokees: in a one-year period, nearly 219,500 Georgians enrolled in lotteries to sate a land hunger the lottery system fueled.

Advertisement for Gold and Land Lotteries. Published in the Southern Banner, August 17, 1832, p. 3. Athens Historic Newspapers Archive, Digital Library of Georgia.

The drums turned from late October 1832 through April 1833. Publications broadcast the names, counties, and lot numbers of winners, sparking a rush of land speculation.6Gold & Land Lottery Register (Milledgeville, GA: Grieve and Orme, 1833); Prizes Drawn in the Cherokee Gold Lottery of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Quality, with their Improvements and Drawer's Name and Residence (Milledgeville, GA: M. D. J. Slade, 1833); Robert S. Davis, Jr., The 1833 Land Lottery of Georgia and Other Missing Names of Winners in the Georgia Land Lotteries (Greenville, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1991). In December 1833, the state held a final lottery to finish dismantling the Cherokee Nation in Georgia. Some fifteen hundred remaining parcels and fractional parcels were awarded to Georgians. Month after month, Cherokee delegations lobbied Congress for redress while President Andrew Jackson sustained state initiatives and Georgians grew impatient for possession. As rising tension elevated the potential for violence, numbers increasingly favored the Georgians. Fewer than nine thousand Cherokees lived on land sought by nearly 220,000 Georgians and awarded to 54,500 winners.7The 1835 Cherokee census, undertaken by the federal government in anticipation of removal, enumerated 8,945 Cherokees in Georgia. Inaccuracies and contradictions derived from the refusal of some Cherokees to participate, the movement of families across state lines to avoid conflict or persecution, voluntary emigration after the census but prior to the expulsion, and deaths: "The 1835 Cherokee Census," Monograph Two, Oklahoma Chapter Trail of Tears Association (Park Hill, OK: 2002), 66. Lottery winners exceeded the total number of Cherokees in Georgia by a ratio greater than six to one. The Georgians' avidity for land, the president's refusal to intervene, and the state's oppression of Cherokees provided Rome's founders with "exceptional opportunities for building the largest and most prosperous city" in the area.8Battey, History of Rome, 33–4.

Impatience for Cherokee land and expulsion swept the state. Although state laws barred whites from taking property still occupied by Cherokees, Georgians easily ignored the sanctions. The Cherokee newspaper, The Phoenix, protested in 1832 that "fortunate drawers (so called) of our land have been passing and repassing single and in companies" across inhabited lots. Unconcerned with restrictions, Georgians roved "in search of the splendid lots which the rolling wheel had pictured to their imaginations," cheerfully asking resident Cherokees which parcels they occupied.9The Cherokee Phoenix, Nov. 24, 1832, reprinted in "From the Cherokees," The Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, Jan. 11, 1833, 2, http://www.newspapers.com; The Cherokee Intelligencer, Feb. 23, 1833, 1, March 9, 1833, 4, and May 11, 1833, 1, Grisham-Magruder Newspaper Collection, Unprocessed Manuscript Collection Number 2001, 57, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center, Atlanta (hereafter G-M Collection, AHC). In the winter of 1833, newspapers advertised maps of the Cherokee counties with "all Mountains, Rivers, Creeks, Branches, Roads, ferries, etc. delineated correctly and faithfully." The maps were atlases of opportunity for speculators and entrepreneurs. Enterprising Georgians promoted themselves as land appraisers, guides, innkeepers, attorneys, and merchandizers in the new counties.10Among many, see William J. Tarvin's offer to supply surveyors at New Echota, April 3, 1832, 3, John Dawson's advertisement for his inn at the house known as Cherokee Sally Hughes's place, Sept. 14, 1832, 4, John Powell's offer to test gold lots for lottery winners, Nov. 24, 1832, 3, and James Nisbet's announcement of his law practice in Vann's Valley, Floyd County, April 20, 1833, 3, all in The Southern Banner, http://athnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu. As the year closed, Governor Lumpkin informed the General Assembly that the state now had "settled freeholders across land hitherto the abode of people wholly unqualified to enjoy the blessings of wise self government."11"Message of the Governor to the General Assembly, Nov. 5, 1833," in The Western Herald, Nov. 16, 1833, 4, G-M Collection, AHC.

Cherokee Ruptures and Realignments

Detail of Treaty regarding Georgia's Western Lands, 1802. Courtesy of the Ad Hoc collection, Georgia Archives, University System of Georgia.

From the earliest days of the American republic, federal regulations had guarded Cherokee interests but such protection vanished under Jackson. Encouraging the state's policies as "rights" superior to federal law, he refused to enforce the Supreme Court's 1832 decision that condemned Georgia's sanctions and affirmed Cherokee sovereignty.12The 1802 Compact between the federal government and the state of Georgia provided for federal extinction of Indian land title in exchange for state relinquishment of its western lands. No other state had such a compact. Chief Justice John Marshall handed down the Worcester v Georgia landmark decision on March 3, 1832. Condemning Georgia's laws as "repugnant to the Constitution, laws, and treaties of the United States," the decision confirmed the independent political status of Indian nations, which made their consent to land cessions a legal imperative. For a useful discussion, see Jill Norgren, The Cherokee Cases: The Confrontation of Law and Politics (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1996). In the context of Jackson's defiance, opposing strategies for survival emerged among Cherokee leaders. They could continue seeking Congressional intervention until Jackson's term expired, abandon resistance and emigrate voluntarily, or negotiate in the usual treaty process that cloaked the federal government with a mantle of legality. In the spring of 1833, Cherokee leadership fractured as John and Major Ridge openly abandoned the established policy of refusing removal agreements. Forming alliances with Georgia Governor Lumpkin and federal officials, the Ridges began to seek a treaty.13See, for example, John Ridge to Wilson Lumpkin, Sept. 22, 1833, http://neptune3.galib.uga.edu. Ridge's letter was "of course, not for publication."

Andrew Jackson, ca. 1825–1837. Portrait by Ralph Eleaser Whiteside Earl. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in public domain.

The rupture among the Nation's leaders altered the Cherokee political and cultural landscape. John Ridge's Floyd County home at Running Waters became the setting for meetings with his followers and federal agents to negotiate a treaty and removal.14Justice John McLean met with John Ridge to inform him that Jackson would ignore the decision: see John Ross to William Wirt, June 8, 1832, The Papers of John Ross, Vol. 1, 1807–1839, ed. Gary E. Moulton (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985), 244–45 (hereafter Moulton, ed., Ross Papers); "Memorial of a Council held at Running Waters, Nov. 28, 1834, 23rd Cong., 2nd Sess., Doc. 91, 1–19. Major Ridge, the wealthy proprietor of an Oostanaula River ferry and store five miles from Running Waters, shared treaty party leadership with his son. Just two miles south of Major Ridge's, Ross directed the Nation's adamant refusal to cede land, negotiate treaties, or emigrate west. Commanding loyalty from the majority of Cherokees, Ross led the Nation from his plantation at Head of Coosa, organizing resistance long after Georgia prohibited the operations of his government.

The Ross-Ridge conflict destabilized the Nation. Advocacy of either side led to accusations of treachery and bribery, hardening the leaders' positions and scattering violence among their partisans. Although the three men maintained civility, their supporters demonstrated considerably less restraint. In July 1833, a fight between Ross and Ridge adherents turned Major Ridge's store into a scene of havoc. Beating and knifing one another senseless, the adversaries exemplified the rage felt on each side of the divide.15The Cherokee Intelligencer, July 20, 1833, 3, G-M Collection, AHC; Thurman Wilkins, Cherokee Tragedy: The Story of the Ridge Family and of the Decimation of a People (New York: Macmillan Co., 1970), 246–47. Wilkins points out that federal agents arrested Ross's supporters who started the attack, binding them over to the Floyd County court. While the injured survived and a few were arrested, the opposing strategies could not be reconciled, nor could those who advocated them. A few months later, treaty party adherent Eli Hicks was murdered near Rome by two Ross supporters, Duck and Swimmer, stirring the legislature to offer a reward for their capture.16See, among many other reports of threats, Z. B. Hargrove to Wilson Lumpkin, June 19, 1835, Louise Frederick Hays, comp., Cherokee Letters, Talks, and Treaties (Typescript, Georgia Archives: 1941), 303 (hereafter Hays, comp., Cherokee Letters, GA); Ga. Acts, 1834 (Milledgeville, GA: P. L. and B. H. Robinson, Printers, 1834), 294. In the fall of 1835, the two were killed, allegedly while trying to escape the local guards who arrested them.17Reported in Columbus Enquirer, Oct. 23, 1835, 3, http://enquirer.galileo.usg.edu. An 1835 letter from founder Hargrove to the governor conveyed William Smith's report of "the savage fury of the Ross party" that attacked "a friendly Indian" (that is, friendly to Georgia and John Ridge). The following year sheriff William Williamson hanged Cherokees Barney Swimmer and Terrapin in Rome's first execution.18Z. B. Hargrove to Governor Lumpkin, June 19, 1835, in Hays, comp., Cherokee Letters, GAs, 303–04; Battey, History of Rome, 211, 248 (Battey attributes the hanging to William Smith whose term as sheriff had recently expired); John Ridge to Eliza Northrup, Nov. 1, 1836, American Board of Commissioners, 18.3.1, v. 7, Item 116, in Paul Kutsche, Guide to Cherokee Documents in the Northeastern United States (Metuchen, N. J.: Scarecrow Press, 1986), No. 3137, 238. Although most of these victims cannot be identified with certainty, the 1835 Cherokee census includes an individual named Swimmer on the Etowah River and on nearby Shoal Creek a man named Tarrapin: "Cherokee Census," 37. Rather than the tranquil countryside implied in local accounts, Floyd County was home ground for the intensely partisan and sometimes brutal struggle for the Cherokee Nation's survival. Rome's founders played a part in the contest as they established a town in the midst of the Nation.

The Collapse of Law

Vann Cherokee Cabin, Cave Spring, Georgia, October 2, 2016. Photo by unknown creator. Courtesy of Cave Spring Historical Society.

While the tenuous hold on their lands exacerbated tensions among Cherokees, Floyd County beckoned white Georgians. Some, like founder James Hemphill, took possession of property abandoned by the original Cherokee owners but still occupied by their descendants.19Before emigrating in 1829, Ave Vann received payment from the government for his property, which his son Charles continued to occupy. The same year, the state rented Vann's possessions to James Hemphill, who displaced Charles: Cherokee Valuations, Georgia, RG 75, T496, Reel 28, 40, GAs. See also Jeff Bishop, "The Vann Cherokee Cabin" in "Georgia Cherokee Structures," unpublished manuscript for the National Park Service, 15–16. Others pushed across the Georgia line into the Nation, sometimes naively, with scarce understanding of the confusing laws regarding Cherokee property. In June 1833, Indian agent William Cleghorn wrote Governor Lumpkin for instructions regarding Floyd County intruders who said, "they did not know it was against the law and begs me to let them gather their crops."20William H. Cleghorn to Wilson Lumpkin, June 25, 1833, TCC857, http://metis.galib.uga.edu. Cleghorn earned $124 for 31 days service as Indian agent: Ga. Acts, 1834 (Milledgeville, GA: P. L. and B. H. Robinson, Printers, 1834), 22. No response to Cleghorn's inquiry has been located. Responsible for putting qualified Georgians in possession of abandoned Cherokee holdings, agents like Cleghorn had to determine whether a site was actually abandoned and, if not, prohibit white appropriation. The work proved challenging from nearly every perspective.

Agents followed a moving target as successive legislation added restrictions and deadlines to Cherokee occupancy, which encouraged greater confusion and more intrusion. The laws of 1833 restricted Cherokee residency to 160 acres, facilitating the partial expropriation of Native farms and enhancing the obvious advantages for land-hungry Georgians. Legislation passed in 1835 withdrew all Cherokee rights of occupancy after November 1836. "Their habits and ferocious customs," the law scolded, "make them insensible to the effects of penal sanctions thereby placing our citizens, their wives and children, and all that is dear to them, at the mercy of the savage, stimulated by his vindictive passions."21"An Act to Provide for the Government and Protection of the Cherokee Indians," Georgia Acts, Dec. 20, 1833 and "An Act to Authorize the Issuing of Grants," Dec. 21, 1835, both in Digest of the Laws of the State of Georgia, comp. Oliver Hillhouse Prince (Athens, GA: Published by the Author, 1837), 154, 283 (hereafter Prince, comp., Georgia Digest). Contributing immeasurably to the collapse of law in the Cherokee counties, the rhetoric of state leaders and the press justified and encouraged the seizure of Cherokee land by Georgia citizens.

As the white population of Floyd County expanded numerically and geographically, "the mercy of the savage" was not the problem. Unlike whites, Cherokees struggled to avoid theft, arrests, beatings, and widespread dispossession. Their claims for compensation from the federal government number in the thousands, challenging the assertion that Cherokees posed a threat to whites and suggesting instead that the reverse was true. While the legitimacy of the claims can never be fully verified, their quantity, similarity, and specificity point to patterns of abuse etched in government records and Native memory. Among the records of loss, two point to the founders of Rome. From the rising hill north of Rome called Turnip Mountain, Tekalesahtuhskee reported that "a white man by the name of Hemphill" had forced him "to abandon a ferry and ferry boat on the Coosa River." The two Cherokees who corroborated the claim, under oath, contributed their own recollections that the dispossession occurred in 1830 or 1831, the year James Hemphill moved to Floyd County and displaced a resident Cherokee named Charles Vann.22Tekahlesahtuhskee Claim 29, Penelope Johnson Allen Collection, University of Tennessee Libraries, Special Collection, MS. 2033, M 4, Nashville; Cherokee Valuations, Georgia, RG 75, T496, Reel 28, 41, GAs., 41, GAs. I am grateful to Michael Wren for providing the claim from the Allen Collection as well as additional archival data relating to Cherokee history.

Brainerd: A Missionary Station Among the Cherokees (in Tennessee). Print of a woodcut by unknown creator. Courtesy of the Penelope Johnson Allen Brainerd Mission Correspondence and Photographs collection, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga.

Fear accompanied the erosion of rights for Cherokees like Alley Rain Crow, who couldn't retrieve the livestock that disappeared from her Cedar Creek home. Her family members "were afraid to go back there and look for them," she recalled, the Georgians having been "so troublesome we could not live there any longer." At Head of Coosa, where the founders imagined a city, a notorious rustler named Philpot stole Kolkahlosky's horses but "I did not go after them as I was afraid." Eagle Buffalofish lost his horses, cattle, and hogs to "outrages of the whites" along the Etowah River. White intruders took over Jinny Smith's ten acres of cultivated fields, peach trees, and a corncrib on the Coosa River near the Haweis Missionary Station. The resident missionaries had already been arrested, released, and dispossessed, and had fled to Tennessee. A "white man" stole a slave from Teyane and another took money from her Cedar Bluff home. When Clay's horses disappeared along the Oostanaula River, he "knew the property to be in the possession of whites" but state law obstructed him from regaining anything. "An Indian had no chance in Georgia," he lamented, "as an Indian was not allowed to swear under the laws of that state."23Claims of Alley Raincrow and Kolkahlosky, Marybelle W. Chase, comp., 1842 Cherokee Claims, Skin Bayou District (1988): 173–74, 81; Claims of Eagle Buffalofish and Clay, ibid., 1842 Cherokee Claims, Saline District, Vol. 2 (1992), 156–61 and 302–04; Claim of Teyane (a Creek woman), ibid., 1842 Cherokee Claims, Going Snake District (1989), 317–18; Mission to the Cherokees Annual Report, American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, Vols. 23–26, 103; Evaluation of Cabbin Smith's widow Jinny, Nov. 18, 1836, RG 75, Cherokee Valuations, Georgia, T496, Reel 28, 83–4, GAs. The litany of complaints filled volumes in federal records but few were heard in Georgia courts. The extension of state law invalidated Cherokee testimony against whites.

Along with economic injury, physical threats menaced Floyd County Cherokees. "The usual scenes which our afflicted people experience are dreadfully increased," John Ridge wrote Ross in early 1833. "They are robbed and whipped by the whites almost every day."24John Ridge to John Ross, Feb. 2, 1833, in Moulton, ed., Ross Papers, Vol. 1, 259–60. Alex Tutt moved from the Etowah River into Tennessee, citing "abuse of himself and wife for cruel punishment inflicted upon them by the citizens of the state of Georgia in Floyd County."25Claim of Alex Tull, Chase, comp., Cherokee Claims, Saline District, Vol. 1, 207. According to Indian agent Cornelius Terhune, Georgians Joshua Keys and Jackson Morrison whipped Tutt, Benjamin Dikes stole his cotton and corn, and a man named Henderson appropriated his fields.26Cornelius Terhune, July 8, 1837, personal notes in possession of Donna Baldwin. I am grateful to Donna Baldwin for providing a copy of Terhune's notes from her family records. The white business partner of Major Ridge, George M. Lavender, thought his neighbor Knitts was wrongfully accused of stealing bacon from a storehouse. "I believe he will be proven innocent," Lavender wrote John Ridge, but Knitts was punished with 120 lashes, released, and then arrested again, which impelled him to emigrate. In his claim, Knitts declared, "I would never have left the land of my forefathers as it was dear to me and the land that I loved and I would never have left." He abandoned his home on the Oostanaula River "to be out of their reach."27George N. Lavender to John Ridge, May 3, 1836, in Battey, History of Rome, 212; Big Nitts Claim, Chase, comp., 1842 Cherokee Claims, Flint District, Vol. 1 (1991), 114–17. The suffering reported in Cherokee claims could not have escaped the attention of at least one of Rome's founders. In January 1834, founder William Smith became Floyd County sheriff with responsibility for property advertisements, land sales, lot possession, and maintaining peace and order.28Sec. of State Commission Book 277/34, p. 128, in "History," Floyd County Sheriff's Office, http://www.floydsheriff.com.

Cherokee County, Section 3, District 23, 1832. Map by surveyor John Harvey. Courtesy of the District Plats of Survey collection, Georgia Archives, University System of Georgia.

"Exceptional Opportunities" for the Founders

In addition to nurturing the intimidation of Cherokees, the confusion of squatters, the plethora of laws, and the ambition of men like Rome's founders, Georgia's unique policy of land distribution also succeeded in promoting white settlement. More than two thousand Floyd County lots were awarded to white Georgians, including veterans, widows of veterans, guardians of orphans, and individual household heads. The lottery guaranteed the mobility and speculation that ensured Cherokee displacement. Prize winners sold their winning tickets, purchased ownership grants from the state, sought buyers for their new land, or arrived by the wagonload at their designated property.29A review of lottery maps indicates a total of 2,100 Floyd County lots: Smith, Cherokee Lottery, 274–96. Local newspapers carried columns of advertisements for lots that became available for purchase in the Cherokee counties. Citizens with adequate funds, such as the founders, did not have to wait long for what they wanted.

Top, Cherokee County plat and land grant issued to Stephen Carter, 1834. Courtesy of the Ad Hoc collection, Georgia Archives, University System of Georgia. Bottom, John Ross House, Rossville, Georgia, 1952. Courtesy of the National Park Service.

The lottery wheel had been turning for two months when some of the property the founders desired became available. On January 18, 1833, the sixty-first day of the lottery, Stephen Carter of Fayette County won the lot where John Ross and his family lived.30Lot 244 in the 3rd Section of the 21st District: Gold and Land Lottery Register, 250. Ross's Head of Coosa possessions included his two-story house, sixty-five acres of cultivated fields, a kitchen, work house, smoke house, blacksmith shop, wagon house, stables, slave quarters, corn cribs, orchards, and a Coosa River ferry and landing.31Indian agent William Springer notified the governor in 1834 that Ross's improvements extended onto Lots 237 and 243 as well as across the Coosa River. His home was located in Lot 244: William G. Springer to Governor Lumpkin, Feb. 5, 1834, Hays, comp., Cherokee Letters, GAs, 264–65; Moulton, ed., Ross Papers, Vol. 1, 130. Estimates of the property's value exceeded $6,000 while the ferry was appraised separately at $10,000.32Cherokee Register of Valuations, RG 75, M 574, Reel 8, File 5, 501–02, National Archives. As his winning ticket increased in value, Carter waited to take possession of the Ross home. The ferry, however, was a more pressing matter, at least for Rome's founders. While Ross remained in residence, Philip Hemphill gained partial ownership of his ferry and landings, filing deeds in the Floyd County courthouse where he served as Inferior Court clerk. Hemphill subsequently sold a portion of his interest to Hargrove who, in turn, entered into partnership with William Smith to control the ferry's operations.33Roger Aycock, "Control of Floyd Ferries," Rome News Tribune, Nov. 28, 1971, 9.

The founders' acquisitions exemplify the economic and political interconnections that displaced Cherokees. Capitalizing on the opportunities provided by the lotteries, they also took advantage of state laws that targeted Cherokee occupation and created land markets for dexterous white Georgians. Long after Rome was settled, Wesley Shropshire recalled his 1834 visit to the town. "William Smith owned most of the land about Rome," Shropshire remembered, and "rode with me several days to buy land." When they found someone with three lots to sell, Smith "sent for Phillip Hemphill, thought he would take one, which he did," leaving the remaining two for Shropshire. The other founders were equally busy. According to Shropshire, Hargrove "owned the ferry landing" and Mitchell "owned the Ross place and land and sold it to Smith."34Wesley Shropshire to Editor, Dec. 1, 1891, reprinted in Roger D. Aycock, All Roads to Rome (Roswell, GA: W. H. Wolfe, 1981), 46. Shropshire was elected sheriff in 1838: Sec. of State Commission Book 277/34, in "History," Floyd County Sheriff's Office, http://www.floydsheriff.com. For such men, personal wealth facilitated the exploitation of the lottery system and the accumulation of Native possessions; state policy encouraged their ambition, supporting the establishment of homes, businesses, and even a city without concern for federal sanctions or Native residents. It was a combination that was disastrous for the Cherokees of Georgia.

Copy of Sketch for the Layout of Rome, Georgia, 1834. Drawing by Daniel R. Mitchell. Courtesy of Rome Area History Museum.

Day after day the lottery's whirling chits gave Cherokee land to acquisitive citizens. On February 8, 1833, another prize spun out to fan the ambitions rising among Rome's founders. Major Pierce (Pearce) of Hancock County won Lot 245, a property conforming to the idyllic tale of Hargrove and Mitchell's chance meeting with Hemphill. Bordering the Etowah River where its convergence with the Oostanaula formed the Coosa, the lot lay directly across the Oostanaula from Ross's home.35Pierce won Lot 245 in the 3rd Section of the 21st District on the 79th day of the drawing, Feb. 8, 1833: Gold and Land Lottery Register, 343. When the founders acquired Pearce's property, they designated it as the city center and set aside a portion of Ross's land across the river for future expansion. Mitchell sketched a plan for town streets and residential lots, leaving an unmapped area fronting the Etowah River for William Smith's eagerly anticipated racetrack.36Desmond, Georgia's Rome, 32. The Ross family lived less than a mile away.

"Ridding Georgia of this troublesome population"

As white Georgians mapped and planned and purchased, Cherokees found ways to resist state policy and citizen aggression. Ross maintained a strategy of challenging Georgia's belligerence through the courts. In August 1834, he informed the Nation's attorney, William H. Underwood of Rome, of threats to his residency. "The town lots on my premises," he wrote, "are advertised to be offered at public sale on the 26th." Lawyers had advised him "to apply for a Bill to enjoin these offenders" and "restrain further trespass."37John Ross to William H. Underwood, Aug. 12, 1834, in Moulton, ed., Ross Papers, Vol. 1, 300–01; Mary Young, "The Exercise of Sovereignty in Cherokee Georgia," Journal of the Early Republic 10, no. 1 (Spring 1990): 43–63. State newspapers of 1834 and 1835 carried numerous articles about the conflict between Cherokee Circuit Judge John W. Hooper and Lumpkin. Seeking an injunction to protect his property, Ross brought suit against founders Smith, Hargrove, Mitchell, Philip Hemphill, and John Lumpkin.38John Ross and Family v. Philip W. Hemphill, William Smith, Zachariah B. Hargrove, Daniel R. Mitchell, Terrell Mayo, and John H. Lumpkin, October, 1834, in Moulton, ed., Ross Papers, Vol. 1, 313. Roger Aycock states the suit was brought Aug. 16, 1834: Aycock, "Floyd Ferries," Rome News Tribune, Nov. 28, 1971. The suits were dismissed: Barron and Irwin, Attorneys' Claims, RG 75, E 235, 1834, National Archives. He emphasized to Underwood that such lawsuits "must go on with energy and earnestness" to assert the legitimacy of Cherokee rights.39Judge Hooper issued numerous injunctions on behalf of Cherokees. See Lumpkin, "Annual Message 1834," and Lumpkin to William N. Bishop, Dec. 23, 1834, Wilson Lumpkin, The Removal of the Cherokee Indians From Georgia, Vol. 1 (New York: Dodd, Mead and Co., 1907), 145–50, 271–3 (hereafter Lumpkin, Removal). The cases charted Ross's resistance as a political strategy. Although lawsuits faced near-certain dismissal, the use of judicial systems temporarily snarled the efforts of Georgians to appropriate properties, publicized the sophistication of the so-called savages, and created an enduring record of the Nation's struggle against Georgia's oppression.

Wilson Lumpkin, Governor of Georgia, ca 1838. Print by unknown artist. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3a17596/.

Outraged by judicial delays to his removal goal, Governor Lumpkin tried to block the injunctions, seeking their reversal and launching an investigation into the activities of the Superior Court judge who authorized them.40Founder Z. B. Hargrove represented the state in its investigation. House Resolution, Ga. Acts, 1834, 338–39; "The Hooper Case," The Southern Banner, May 20, 1835, 1–2, http://athnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu. Lumpkin's address to the legislature regarding Judge Hooper is reported in The Southern Banner Nov. 8, 1834, 2–3, http://athnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu. Hooper's term expired before the report, which supported his rulings, was released. In December 1834, he intensified pressure on resident Cherokees. To accelerate their dispossession, he appointed his aide, William N. Bishop, as Cherokee agent. Bishop commanded the Georgia Guard, which the state had established and armed in 1830 to maintain its sovereignty inside the Cherokee Nation. Consisting of about forty men from the Cherokee counties who ardently supported Lumpkin's policies, the Guard had appropriated a mission site for headquarters, established a crude jail, operated with no legal restraint, and reported directly to the governor. Since 1833, they had spied on Ross and his associates, arrested and dispossessed errant or vulnerable Cherokees, and protected treaty party members and their property from dispossession. "I am happy to learn your intention," Bishop had written Lumpkin in 1833, "of ridding Georgia of this troublesome population."41John Ridge asked the governor to exempt the property of treaty party members until they had emigrated: John Ridge to Wilson Lumpkin, Sept. 22, 1833, http://neptune3.galib.uga.edu; William Bishop to Wilson Lumpkin, Sept. 16, 1833, http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~gachatto/corr/cherokee.htm.

In a "private and confidential" letter enclosed with Bishop's appointment, Lumpkin denounced the "reprehensible" judicial challenges to state authority. He acknowledged that the language of the state's Cherokee legislation seemed "vague and ambiguous" but insisted its purpose remained obvious. The legislature and "our people," he argued, intend that "the rightful owners" be given "immediate possession" of Cherokee premises. Regardless of the "artifice of lawyers or the embecility [sic] of judges," Lumpkin welcomed responsibility for "discharging this duty."42Wilson Lumpkin to William N. Bishop, Dec. 23, 1834, in Lumpkin, Removal, Vol. 1, 272–73. Like Andrew Jackson, he denied the authority of the national and state judiciary, including jurists elected to office by Georgians. As Lumpkin realized, the elimination of legal redress left Cherokees with few options.

Claim by William N. Bishop for Land Owned by Chief John Ross, March 17, 1835. Courtesy of the Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

On March 17, 1835, Bishop recorded his execution of Lumpkin's "duty" in Rome. "As agent for the state of Georgia," he announced, "I have this day put the Legal claimant of Lot of Land No. 244 in the 23rd District of the 3rd Section in full and entire possession of the Same of which John Ross was the Indian occupant." The notice stated Ross had "forfeited his right of occupancy under the Existing Laws of this state."43William N. Bishop, March 17, 1835, in Moulton, ed., Ross Papers, Vol. 1, 333. Bishop's assertion alluded to legislation that transferred to lottery winners all lots in the possession of Cherokees who had agreed in 1819 to become private landowners and state citizens where their lots lay. John Ross had made such an agreement for a tract in Tennessee he never occupied. Like most who entered the 1819 agreement, he sold his reserved lot for a profit and moved elsewhere in the Cherokee Nation.

A witness recalled later that Ross was out of town when Bishop and Hargrove summoned William Smith, John Lumpkin, and others "to go over the Oostanaula River and put Mitchell in possession" of Ross's house. Ross's wife, Quatie, initially "refused to give possession" to the Georgians, but Bishop "ordered a bureau thrown outdoors." His tactics of intimidation prevailed. As "four men took hold of it," Quatie Ross relented, turned over the second floor of her home, and signed a pledge "to give the house up in ten days."44Shropshire to Editor, Aycock, All Roads, 45–6. She gathered her children and left for Cherokee Nation land in Tennessee. When Ross returned from Washington later in the month, he found his home occupied by Georgians who adhered to "the Existing Laws of this state," but not to those of the United States.

Across the landscape, Cherokees and whites could watch Georgia's uneven application of justice. Just north of Ross's, Major Ridge continued living in his Oostanaula River home for two more years, earning proceeds from his store and ferry until he chose to emigrate with his family and possessions. To the northeast, John Ridge remained at his Running Waters home for the same period, benefitting from plantation and Coosa River (Alabama) ferry income until shortly before his voluntary departure.45In a June 17, 1835 letter to Bishop, Lumpkin directed him to "be vigilant in protecting and defending John Ridge and his friends" and to arrest Ross if anyone could be found to "sign an oath against him": Lumpkin, Removal, Vol. 1, 356. After passage of the New Echota Treaty, federal officers also issued instructions to protect the Ridge properties. Ultimately, however, even the Ridges were dispossessed: see testimony of General John E. Wool, Sept. 4, 1837, reported in The Burlington Weekly Free Press, Feb. 9, 1838, 1, http://www.newspapers.com/image/76504046/?terms=Coosa. The governor instructed the Georgia Guard to hold in abeyance the winners of the Ridges' properties while ensuring the dispossession of Ross and his advocates. Such selective application of law marked the memories of the Cherokees expelled from Georgia. John Ross, leaving the gravesites of his father and infant child, and his "houses, farms, public ferries and other property," followed his family to Tennessee.46Ross's own account is in his "Memorial to the Senate and House of Representatives, June 21, 1836," Moulton, ed., Ross Papers, Vol. 1, 427–444, account of dispossession on 432–33. The exiled leader continued to govern the Nation, proclaim the Cherokee position in the national press, and lead embassies to Congress to seek relief from Georgia aggression. Meanwhile, Head of Coosa became available for the "splendid new city" of Rome.

Detail of Map of Floyd County, 1871. Map published by William Philllips. Courtesy of County Maps collection, Georgia Archives, University System of Georgia.

The Treaty of New Echota

Soon after the Ross dispossession, a Floyd County meeting served as a turning point in the removal crisis. In July 1835, John Ridge and federal agents called for a grand council of the Cherokee Nation at Running Waters, purportedly to determine the procedures for distributing federal annuities. The presence of enrolling agent Benjamin Curry and treaty commissioner John Schermerhorn, however, exposed its true purpose as presenting a removal treaty to as many Cherokees as possible. Summoned by Ross because of the vote on annuities, approximately four thousand men, women, and children from four states converged on John Ridge's expansive property. While waiting for the meeting to begin, they made camp, set up areas "for wrestling and other athletic exertions," and honed their stickball skills. In an atmosphere of civility strained by heavy rains and inadequate provisions, the treaty party assembled alongside Ross and the Cherokee National Council, agent Curry, commissioner Schermerhorn, US Army officers, translators, a recording secretary, and a few Georgians. Drumming their arrival, the Georgia Guard stationed themselves in two camps, one less than a mile away to the north and the other southward at Major Ridge's where the treaty commissioner was staying.47"Journals of Return John Meigs While Secretary to the Commissioners Authorized to Negotiate with the Eastern Cherokees, 1835," trans. Alice H. Meigs, John Meigs Collection, no. 83.01, Oklahoma City Historical Society Research Center, Oklahoma City, Ok (hereafter OCHS). The federal records pertinent to the Running Waters Council are in 25th Cong., 2nd Sess., Doc. 120, 396–447. The sights and sounds, crowded roadways, masses of people, smoke from fires, and odors of cooking must have drawn the notice of even the most preoccupied Floyd County citizens.

New Echota: Cherokee National Capital, Calhoun, Georgia, June 19, 2008. Photograph by Flickr user Ashe. Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND-2.0.

For three days the assembly listened to speeches by Schermerhorn, Curry, John and Major Ridge, and Ross. Schermerhorn read Jackson's letter to the Cherokee Nation, which John Ridge had suggested, promoting removal and promising its benefits. The commissioner next introduced a provisional removal treaty and explained each section to the hushed assembly. Finally, the annuity alternatives were presented. John Ridge sought a per capita distribution of the annuities while John Ross favored the custom of depositing the money into the national treasury. Signifying far more than an opportunity to express preferences regarding the distribution of money, the annuity question provided a public referendum on the two opposing leaders and their policies. Of the more than 2,553 men who voted, 114 endorsed Ridge's annuity proposal and the remaining 2,439 sided with Ross.48"Meigs Journals," OCHS. As a measure of each leader's strength, the meeting orchestrated by the Ridges and government agents had backfired. The annuity vote publicly confirmed the weakness of Ridge and his coalition and, instead, underscored the commitment of Cherokees to Ross and the National Council. To obtain a treaty, the state and federal governments would have to proceed without the Cherokee government and the majority of Cherokee citizens.

The Running Waters council was the last official gathering of the Cherokee Nation in Georgia. In December 1835, Major Ridge and treaty party members traveled to New Echota for a summit with Schermerhorn and removal operatives. Without the participation of any representatives of the Cherokee government, they signed the agreement ceding all southeastern Cherokee land and committing the Nation to removal within two years. John Ridge, absent from the meeting for a conference in Washington, added his signature as soon as Major Ridge presented the document to him.49Major Ridge headed the delegation that took the signed treaty to Washington, where his son John added his signature on Feb. 3, 1836: Wilkins, Cherokee Tragedy, 277–78. On May 23, 1836, Congress ratified the treaty, which Jackson promptly signed. The treaty gave Cherokees two years to emigrate voluntarily. After the deadline, forced removal would begin.

In this letter to Governor Lumpkin, John Ridge sought protection for the property of Major Ridge and treaty advocate Alexander McCoy two years before signing the Treaty of New Echota. Courtesy of the Georgia's Virtual Vault website, Georgia Archives, University System of Georgia.

While Ross vigorously condemned the agreement, a new wave of Georgians caught the scent of removal. Less than a month after ratification, John and Major Ridge implored "our friend" the president for protection from Georgians. "We are not safe in our homes," they grieved, "the lowest classes of the white people are flogging the Cherokees with cowhides, hickories, and clubs." As the majority of Cherokees had long experienced, the treaty party now "found our plantations either taken in whole or in part" regardless of "protestations of innocence and peace." Their persecutors extended beyond "the rabble" and included "even parties of the peace and constables," a condemnation of former allies like William Smith and Colonel Bishop. Beseeching Jackson to "write to the Governor of Georgia," the Ridges pleaded, "above all send us regular troops to protect us from these lawless assaults."50John Ridge and Major Ridge to Andrew Jackson, June 30, 1836, RG 75, M 234, Reel 80, frames 0488–89, National Archives. The treaty provision that guaranteed protection of the Cherokees until their departure had little effect on Georgians who welcomed another opportunity to disregard federal imperatives.

Agents of Expulsion

As conditions deteriorated among Cherokees, the federal government began preparing for their removal. General John E. Wool assumed operational command with headquarters near the Cherokee Agency in Tennessee, designating New Echota as the center for removal in Georgia. Sharing the goal of Cherokee expulsion, soldiers and civilians moved to the former Cherokee capital. Two Georgia militia companies mustered into federal service and erected barracks and stables out of wood from the Cherokee Council House. Having completed his final term as governor, Wilson Lumpkin found housing as one of two commissioners empowered to accept or reject Cherokee evaluations and spoilation claims. Rome citizen James Liddell replaced Lumpkin when he resigned to take a US Senate seat. As commissioners reviewed thousands of petitions for property compensation, Cherokees lined up for the rations and clothing the treaty provided the indigent. John Ridge took up temporary residence as chair of the Cherokee committee advising the commissioners about claims, endorsing or denying their validity, and identifying individuals capable of removing themselves without supervision. Disbursing officers traveled back and forth with bank funds, including a loan of $10,000 from Rome's new Western Bank of Georgia that was governed, in part, by the city's founders.51Sarah H. Hill, "Cherokee Removal Scenes: Ellijay, Georgia, 1838," Southern Spaces, https://southernspaces.org/2012/cherokee-removal-scenes-ellijay-georgia-1838; Lumpkin, Removal, Vol. 2, 85; "An Act to Incorporate the Western Bank of Georgia," Prince, comp., Georgia Digest, 123; Senate Report 277, 23rd Cong., 2nd Sess. (Washington, D.C.: Blair and Rivers, 1839), 94–6. The Western Bank's directors included Z. B. Hargrove, Philip W. Hemphill, and Daniel Mitchell: The Southern Banner, Aug. 19, 1837, 3, http://athnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu. With the collaboration of Georgians and the treaty party, the business of removal began.

Top, Cherokee moccasin, ca. 1830. Courtesy of Chieftains Museum/Major Ridge Home. Image provided by Sarah H. Hill. Bottom, Cherokee purse, pre-1840, made by a student at the Moravian Mission School, James Vann plantation, Georgia. Courtesy of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Chief Vann House Historic Site.

Floyd County citizens became appraising agents, carrying pens and notebooks from one house to another to assess properties Cherokees would be forced to abandon. Philip Hemphill and James Liddell began work in their assigned section on September 1, 1836, filling more than forty pages with notes of Cherokee possession and loss. Among prosperous households such as those of Ross and the Ridges, they examined dwelling houses, spring houses, stables, shops, kitchens, slave cabins, hen houses, fish traps, fenced lots, mills, orchards, and smoke houses. Their work took them to John Fields's inn, "a good stand at the forks of the road leading to Ross and Ridges homes" and Yonah Killer's ferry on the Oostanaula, the apple trees of Brush in the Water, Little Nelly's cook house, the garden lot of Susan Peacock, and Tarloke's loom house.52Cherokee Valuations, Georgia, RG 75, T496, Reel 28, frames 10, 20, 23, 31, 46, 55, GAs. From Vann's Valley past Head of Coosa and Running Waters, Dirt Town to Raccoon Town and Armuchee, and through Chattooga and Spicewood valleys, the agents eyed fields, farms, and homes, placing a value of eighty cents on each good peach tree and three dollars on every cleared acre of good land. They estimated most cabins at four dollars unless they had plank floors, shingle roofs, or brick chimneys that added a half dollar or more to the value. Earning four dollars a day as federal employees, Floyd County denizens moved from lot to lot assessing Cherokee economic worth.

In the adjacent section of Floyd County, Joseph Watters and Samuel Burns recorded more than one hundred additional pages of possession and loss. They repeatedly noted Cherokees had been divested of fields, homes, ferries, mills, livestock, money—everything they had built or cultivated. Dispossessions had begun soon after the extension of Georgia laws in 1830 and accelerated each year, becoming particularly widespread in 1836. It is little wonder the appraisers occasionally encountered resistance to their prying. On the Etowah River, Watters and Burns reported Chunahyahee or John Longfoot "refused to show his improvement, does not believe he will be paid for it." Nearby, Chuqualalagee, his mother, and brother "all refused to show any part of their improvements or give the number of their families." Their neighbors on either side had already been dispossessed. When the Floyd County evaluators finished their work in December, they turned over their records to James Hemphill, who delivered them to commissioner Lumpkin at New Echota.53Ibid., 66–7; Wilson Lumpkin and J. M. Kennedy to Benjamin F. Curry, Dec. 14, 1836, Lumpkin, Removal, Vol. 2, 77–8.

Regardless of evidence of the state's victory over the Cherokees—a ratified treaty, appraisal agents, Native dispossession, abandoned mission stations and schools, an expanding white population, the Georgia Guard, and federalized troops—many Georgians became more fearful, a reaction aggravated by the behavior and rhetoric of their leaders and an irresponsible press. "The Cherokees," warned the Macon Telegraph, "only wait a good opportunity to break out into open hostilities." According to the paper's unnamed sources, Cherokees were "abandoning their cornfields and cabins and making other movements plainly indicating sinister designs."54Reprinted in The Federal Union, June 2, 1836, 2, G-M Collection, AHC The Columbus Herald of August 2, 1836, passed along the fiction "the Ross party had risen in their wrath and were destroying all before them." Georgians, the paper threatened, should anticipate "a new scene of savage depredation" comparable to the Seminole and Creek removal wars.55Reprinted from The Columbus Herald in The Savannah Republican, Aug. 8, 1836, 3, http://savnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu. See also Sarah H. Hill, "To Overawe the Indians and Give Confidence to the Whites: Preparations for the Removal of the Cherokee Indians from Georgia," The Georgia Historical Quarterly 95, no. 4 (2011): 465–97. Knowing the treaty had been obtained from a dissident faction over the objections of the Cherokee government, many Georgians assumed the worst. Afraid of those they lived among and vastly outnumbered, they demanded armed intervention.

Fear and Force

Photograph of Daniel R. Mitchell, ca. 1830. Courtesy of Rome Area History Museum.

Introduced first in Floyd County, the militarization of the Cherokee homeland began in the two-year term of Governor William Schley soon after treaty ratification. Schley sent weapons to Floyd County in response to correspondence from James Hemphill. Persuaded by "several resolutions of the citizens of Floyd" conveyed by Hemphill, the governor believed "there was more danger to be apprehended" in Floyd and Walker counties "than any other part of the Cherokee Circuit." Schley took the additional step of ordering Hemphill to raise and station a battalion in Floyd County to prevent Creeks from entering the state and to "keep the Cherokees in check." The founders quickly joined the military initiative. Daniel Mitchell assembled a cavalry that included William Smith, Philip Hemphill, James Liddell, and Joseph Watters (who replaced Mitchell as captain in August). John Lumpkin became captain of one of Rome's new militia companies. By July, 200 men had set up headquarters on the Coosa River 18 miles from Rome. From the post they named Camp Scott (in honor of Creek removal commander Winfield Scott), the companies patrolled the Cherokee counties, expelled a few Creek refugees, and mistakenly arrested, then released, some resident Cherokees.56William J. W. Wellborn to William Schley, June 19, 1836, http://neptune3.galib.uga.edu; "Governor's Message," Nov. 8, 1836, in The Southern Banner, Nov. 19, 1836, 1–2, http://athnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu; James Hemphill to D. R. Mitchell, June 18, 1836, Copies 1, 2, 3, and 4, Louise Frederick Hays, comp., Georgia Military Affairs (1941), GAs, 123–24 (hereafter Hays, comp., GMA); Floyd County company elections May 28 and June 10, 1836, Vertical Files, Military, Floyd County, GAs; Gordon Burns Smith, History of the Georgia Militia, 1783–1861, Vol. 2 (Milledgeville, GA: 2000), 337.

Abandoned three months later, the ephemeral Camp Scott signifies the link Georgians made between fear and force in the removal era. Cherokees, by all reports, remained peaceful, continued to plant and build, and waited for Ross's instructions. Informants repeatedly told Governor Schley and his successor, George R. Gilmer, that Cherokees manifested no hostility. Nevertheless, from the executive office to individual households, Georgians feared a Cherokee uprising and demanded preemptive action. They sought weapons and arms for themselves and objected to the use of outside troops. As incoming federal troops enforced their responsibility to protect Cherokees until the removal deadline, Georgians became suspicious of the soldiers' loyalties. Commissioner Lumpkin insisted to the president, the enrolling agent, Wool, Schley, and Secretary of War Poinsett that removal forces in the state consist only of Georgians. The attitudes of federalized Tennessee troops and US Army officers, he wrote, insulted "every man who feels the true spirit of a Georgian."57Wilson Lumpkin to William Schley, Sept. 24, 1836, Lumpkin, Removal, Vol. 2, 49–50. Mistrust of outsiders spread through the Cherokee counties where federal troops were expected to serve. A Floyd County citizen complained to the governor that soldiers who were not Georgians "have become decidedly the Indians friend when ever they have entered the nation or they all come prejudiced against Georgia."58John T. Storey to George R. Gilmer, January 25, 1838, RG 4-2-46, File II Names, Folder 148, GAs. No other state suffered so much suspicion; no other state made such a demand. The months between ratification and removal were rank with tension between Cherokees and Georgians, and between Georgians and everyone else.

In the fall of 1837, Schley again militarized the Cherokee counties, calling for militia companies in each. He notified the new president, Martin Van Buren, that he intended to raise two regiments of Georgia troops who could "take the field at a moment's notice" and impress on "that savage and deluded people" the certainty of their expulsion. "I have deemed it my duty," he informed the president, "to protect from murder and rapine the unoffending citizens" of Georgia. Like Lumpkin, Schley argued for state militia rather than "any other species of troops" because their "wives, children, and property are the stake." Raising militia five months before the deadline, arming citizens who were already hostile to the Cherokees, and establishing a military force independent of federal authority did not diminish the anti-Indian rhetoric of the press, state leaders, or fearful citizens, and alarmed the federal administration. Secretary Poinsett lectured Schley that the president could not "perceive the propriety of sanctioning the measure at this time." Just as federal law failed to deter Lumpkin, however, the administration's objections did not dissuade Schley.59William Schley to J. R. Poinsett, Sept. 9, 1837, RG 107, M221, Reel 118, frame 875, National Archives; Poinsett to Schley, Sept. 20 and Oct. 11, 1837, 25th Cong., 2nd Sess., Doc. 120, 317–18, 328–29; "Cherokee Troops," The Southern Banner, Sept. 30, 1837, 2, http://athnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu.

Floyd County and its leaders played central roles in the revived military presence. The leader of the new militia regiment was Colonel Samuel Stewart of Rome, who raised ten volunteer companies "for the protection of the citizens of the Cherokee Country, and for the removal of Cherokee and Creek Indians."60"An Act to Provide for Protection and Removal," Prince, comp., Georgia Digest, 154–55. John Lumpkin distributed weapons to the Rome companies, collecting the arms left at Camp Scott the previous year.61Robert Ware to George Gilmer, Jan. 7, 1838, and W[illiam] F. Lewis to George R. Gilmer, Feb. 25, 1838, both in Hays, comp., GMA, Vol. 9, 5, 29. Documenting the county's increase in population and its enthusiasm for military action, Joseph Watters wrote from his home (named The Hermitage, honoring Andrew Jackson) that the Floyd County militias included five hundred officers and privates "lyable to bear arms."62Joseph Watters to George R. Gilmer, ibid., March 5, 1838, 69; Watters to Miller Grieve, May 23, 1838, in Hays, comp., Cherokee Letters, 723–24. The possibilities of combat tantalized men like Captain William F. Lewis, who informed the governor that his Floyd County company was impatient to "be in survis in order to keep down hostilities" and objected to orders "to hold our selvs in redenes" with "no prospect of survis." Additionally, suspicion of outsiders continued to taint perceptions of reality. Lewis told the governor his men found it "wors then all we ar to have other troops sent in to introod on our rights." Regardless of their eagerness or their presumed rights, the ten volunteer companies activated in April 1838 did not participate in Cherokee expulsion but instead "investigated all rumors of danger" identified in the "frequent petitions" received from Georgians in "different parts of the [Cherokee] Nation."63William F. Lewis to George R. Gilmer, March 26, 1838, in Hays, comp., GMA, Vol. 9, 84; Samuel Stewart to Charles J. McDonald, Feb. 26, 1841, http://neptune3.galib.uga.edu; Orders to Colonel Samuel Stewart, April 5, 1838, printed in The Western Georgian, April 21, 1838, 2, G-M Collection, AHC.

Lost property claim of Nah 'ny of Running Waters identifying the white man who stole her livestock, Georgia, 1837. Cherokee Indians Relocation Papers, MS 0927, Georgia Historical Society. Image provided by Sarah H. Hill.

While Schley was running (unsuccessfully) for reelection and promising to defend Georgians from Cherokee depredations, the treaty party emigrated. In March 1837, Major Ridge joined a departing group and left with his family, slaves, household goods, clothing, appraisal money, and, perhaps, a portion of "the prudent advances" commissioner Lumpkin made "to the wealthy and intelligent" in order to "remove opposition to the treaty among the most influential."64Wilson Lumpkin to C. A. Harris, March 22, 1837, Lumpkin, Removal, Vol. 2, 103–05. Ridge's lucrative store in Rome where Cherokees and Georgians had visited, traded, and fought in previous years remained in the possession of his white partners George Lavender and founder Daniel Mitchell. After completing advisory work at New Echota in late summer, John Ridge also emigrated, traveling first to Wills Valley, Alabama to settle business affairs. In addition to his slaves and two other families, Ridge's entourage consisted of his wife and their six children born in Rome, including two-year-old Andrew Jackson Ridge. From Alabama, the Ridge contingent detoured to Nashville to pay their respects to the former president, who had retired to The Hermitage. John Ridge's group arrived in Indian Territory in late November 1837 to find that "perfect friendship and contentedness prevail."65Wilkins, Cherokee Tragedy, 292–97, quotation on 298. If so, their new homeland presented a contrast to the one they had left in Floyd County. The Rome militia companies were trying to muster every week and federal troops were on the way.66Captain Lewis complained to Governor Gilmer about the requirement to muster every week: Lewis to Gilmer, March 26, 1838, in Hays, comp., GMA, Vol. 9, 84.

Erasing Cherokee Identity

The task of removing thousands of Cherokees from their homes while preventing their escape or revolt required a build-up of military and citizen support that began soon after ratification and continued past the removal deadline. Month by month, troops cleared woodland, muddied streams, rutted roads, and filled the air with sound and smoke. Ambitious Georgians set up stores and grog shops, rented rooms in their homes and oxen from their fields, drove wagons, shoed horses, ferried passengers, sold supplies, and worked as physicians and matrons. The work of removal interlaced the lives of local civilians and the hundreds of soldiers in their midst. When arrests began in late May 1838, more than two thousand men in twenty-nine Georgia companies had been mustered into federal service and stationed at fourteen posts. In accord with the demands of citizens such as Wilson Lumpkin, almost all the removal troops in the state were Georgians and under the direction of the state militia commander rather than a federal officer. In a nod to US concerns about local prejudices, however, all but two companies came from beyond the Cherokee periphery.67Hill, "Cherokee Removal Scenes," Southern Spaces. Contrary to state and federal policy, Captain Samuel Farris of Walker County commanded the companies in his own county; as removal began, Captain H. I. Dodson commanded a Tennessee company at Fort Hetzel in Ellijay. Farris's work is examined in Stephen Neal Dennis, A Proud Little Town: LaFayette, Georgia 1835–1885 (LaFayette, GA: Walker County Governing Authority, 2011).

Letter from John Means to George Gilmer, March 6, 1838. Courtesy of File II Names collection, Georgia Archives, University System of Georgia.

The first of two military stations in Floyd County was established in April 1838 in response to a local suggestion. Replying to Governor Gilmer's February inquiries, the Cherokee Nation's former attorney, Judge William H. Underwood, reported that he saw "no appearances or an intention on the part of the Indians to commence hostilities." Nonetheless, the judge thought it wise "to keep up a show of force" to intimidate the Cherokees. He advised Gilmer to "station one company on the line between Floyd and Cass Counties near General Miller on the Etowah River," a location not far from Underwood's home.68George R. Gilmer to James Gamble, Thomas McFarland, William Smith, James Hemphill, William H Underwood, and others, Feb. 13, 1838, RG 1-1-1, Governor's Letter Books, M240, Reel 35, frames 129–31, GA; William H. Underwood to George R Gilmer, Feb. 28, 1838, in Hays, comp., Cherokee Letters, 672–73. In early March, Gilmer ordered into service Captain John S. Means of Walton County, who received instructions to "take post in Floyd County near the dividing line between it and Cass County, and also near the Hightower [Etowah] River."69George R. Gilmer to William Lindsay, March 14, 1838, RG 1-1-1, Series 1, Governor's Letter Books, Box 13, 197, GAs; James Mackay to A. R. Hetzel, April 2, 1838, RG 92, Entry 357, Misc. Corr., Box 6, National Archives. Soon after, Means mustered in at New Echota with a company of sixty-five privates, three officers, and four servants (likely slaves), then advanced to a site on the Etowah River as Underwood had suggested. By April 15, soldiers were at work constructing a fort one mile east of General Andrew Miller's between the Etowah River and the nearly parallel Etowah road.70John H. Means to George R. Gilmer, April 15, 1838, Hays, comp., GMA, Vol. 9, 94. The fort site has been identified by the Georgia chapter of the National Trail of Tears Association through the meticulous work of former chapter president Jeff Bishop. Cherokees and Georgians lived nearby, scattered along the river and its tributaries.

Over the next month, company privates earned fifteen cents a day in extra-duty pay felling trees, clearing brush, digging trenches, making and installing pickets, and building store houses, a block house, stables, and a hospital. Almost all their tools—axes, ropes, chains, mattocks, shovels, hatchets, hammers, nails, files, and more—came by wagon over pitted roads from Tennessee headquarters eighty-eight miles away. In addition to the transport of construction materials, wagons creaked and groaned to the fort loaded with 200-pound barrels packed with thousands of pounds of bacon, salt, coffee, beans, soap, vinegar, candles, and flour.71See, for example, A. R. Hetzel to A. Cox, April 4, 1838, RG 350, Box 2, Vol. 2, National Archives; Hill, "Cherokee Removal Scenes," Southern Spaces. The supplies could hardly keep pace with the fort's increasing population. Dr. Eldridge W. Allen of Franklin County, who had just completed medical training, arrived to serve as post physician and on May 24, Captain Frederick W. Cook marched in with his Oglethorpe County infantry company, increasing the number of soldiers to 155 men. With removal just two days away, the privates in Means's company must have been relieved to see Cook's troops. They needed help finishing the blockhouse and the fort's entry gate.72Allen graduated from Transylvania University in 1837–38: Medical Thesis on "Acute Rheumatism," libguides.transy.edu/content.php?pid=522103&sid=4295169; RG 92, Entry 9, M745, Reel 13, Vol. 18, 254 and Vol. 26, 377, National Archives; RG 393, M 1475, Reel 1, frames 0319–22, National Archives and Records Administration (hereafter NARA).

William Graham voucher 139 payment for ferriage to William T. Price, May 29, 1838. RG 217, Entry 712, Box 1819, National Archives. Image provided by Sarah H. Hill.

Post quartermaster William Graham worked with Floyd County citizens as he built, supplied, and sustained the fort. To make flooring, he purchased thousands of feet of plank from John Johnston, one of the men who evicted Quatie Ross in 1835.73Shropshire to Editor, Aycock, All Roads, 45–6. From his home a mile from the post, John Miller sold Graham hardware for doors and gates and writing materials for keeping quartermaster records. Andrew Miller supplied oxen to haul logs and install the palisade walls. William T. Price, who owned two nearby lots, and Joseph Watters some ten miles away were among those selling thousands of bushels of corn and bundles of fodder for company horses as well as the horses, mules, and oxen that pulled wagons. Price crossed the Etowah River more than sixty times ferrying soldiers, horses, baggage, and wagons. Wilson R. Young allocated a room in his house for a sick soldier and Henry Frick sold the quartermaster a table and a desk, almost the only furniture in the simple fort. The names of numerous other Floyd County residents—James Hilton, Benjamin Penn, Stephenson Johnston, Benjamin Dykes, Samuel Morgan, Ezekial Graham, Nathanial Burge, and Zachariah Aycock—entered military records as citizens who made removal from Fort Means possible.74A. Cox Settled Account 4849, Box 1218, Entry 712, Abstract A, Sub Abstract 9, Subvouchers 1–15, and Voucher 143, Subvoucher 13; A. R. Hetzel Settled Account 6814, Box 1263, Vouchers 39 (April 16, 1838), 61 (April 21, 1838), 68 (April 25, 1838), and 6 (May 28, 1838), both Settled Accounts in Records of the Accounting Office, Treasury Department, Third Auditors Settled Accounts and Claims, March 10, 1836–April 21, 1845, National Archives. Profiting financially from the expulsion of Cherokees, Floyd County citizens sanctioned Georgia's policies.

A few days before the treaty deadline, post commanders estimated the number of Cherokees in a fifteen-mile radius of their position. Noting that he saw "no sign of hostility," Captain Means presented his survey on May 22 in terms that illuminate the reversal of Cherokee life in less than a decade. Rather than identifying Cherokees by name or even age and sex, he simply provided the total number of people for each cabin he saw. Additionally, he listed Cherokees as occupants of land belonging to white citizens rather than the reverse. Beginning with eight cabins and fifty unnamed Cherokees on "Mr. Putnam's plantation," Means noted thirty in four cabins on Mr. Williams's property and twelve in two cabins at Mr. Mann's. Crisscrossing the Etowah River, he reckoned Natives on the land of Fagin, Price, Lampkin, Wooly, Burgess, and Judge Underwood. He estimated those along the Oostanaula River on Joseph Watters's property and at George Lavender's. The landowners, "who are acquainted with them," assisted Means in his enumeration of the frightened obdurate Cherokees.75John S. Means to William Lindsay, May 22, 1838, RG 393, M1475, Reel 1, frames 0819–22, NARA. More than a military accounting, the survey provides a symbol of removal from Georgia. It consigned the land where Cherokees lived to the Georgians who acquired it and, in the process, erased Cherokee identity.

While Means prepared his fort and men, plans emerged for an additional post near Rome. Assuming the likelihood of "some very unpleasant occurrences," James Gamble had advised the governor to station soldiers in the Chattooga Valley "near the dividing line between Walker and Floyd [counties]." Thomas G. McFarland echoed Gamble's suggestion, adding that there was "a considerable number of Cherokees in that neighborhood and some of them very vicious."76Gamble and McFarland were among the men Gilmer consulted about the number of companies and their placement. James Gamble to George R. Gilmer, March 16, 1838, "Cherokee Removal Letters," www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~gachatto/corr/cherokee.htm; Thomas G. MacFarland to George R. Gilmer, April 2, 1838, in Edward Cashin, ed., A Wilderness Still the Cradle of Nature: Frontier Georgia (Savannah, GA: Beehive Press, 1994), 232. Nothing developed until the second week of May when hundreds of men mustered into federal service at New Echota and learned their assignments. Captain Stephen Malone, arriving with his "servant" Arram and a drafted company from Henry County, was promoted to colonel and ordered to set up the post that became known as Camp Malone.77Compiled Service Records, RG 94, Entry 57, Box 210, (Stephen Malone), National Archives. It seems probable he selected a site north of Rome and perhaps in the area recommended by Gamble and McFarland.78The northern site may also have been Georgia's 15th proposed post planned for Dade County "near Perkins" but never fully manned or utilized.

View of Posts & Distances in the Cherokee nation, to illustrate Maj. General Scott's operations, December 15, 1838. Map by Lt. Erasmus Darwin Keyes, approximating the locations of and distances between removal posts in the Cherokee Nation. Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.