Overview

What happened when the United States set about to remove the entire Cherokee Nation from the South? Who were the participants and how did they proceed? To document the process of Indian removal and restore the missing pieces of a lost history, Sarah H. Hill explores one location in Georgia where a reprehensible federal policy changed the lives and landscapes of Cherokees and Georgians.

Introduction

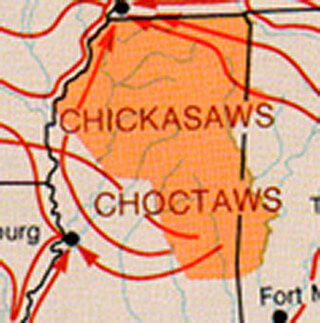

|

| Map of Main Indian Removal Routes from James W. Clay, Paul D. Escott, Land of the South (Birmingham, AL: Oxmoor House, 1989). |

On May 28, 1830 America’s long-standing policy of procuring Native lands for western expansion culminated in Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act. For the next five years the federal government cajoled, bullied, and bribed the southeastern Indian nations to emigrate west of the Mississippi River while the southeastern states asserted sovereignty over Indians and claimed rights to their land. No state was more belligerent than Georgia, justifying its demands for Indian removal by referencing its unique compact with the federal government to eliminate Indian title.1The unique 1802 Compact between Georgia and the federal government settled Georgia’s claim to its western land beyond the Chattahoochee River in return for a pledge to extinguish Indian title to lands within the state’s claimed boundaries. The Cherokee Nation’s claim to an overlapping portion was guaranteed by a series of treaties with the federal government. In 1835 the federal government succeeded in obtaining a treaty with unauthorized representatives of the Cherokee Nation, which Congress ratified on May 23, 1836. The New Echota Treaty allowed the Cherokees two years to remove voluntarily. While Principal Chief John Ross led numerous delegations to Washington to protest the treaty, the majority of Cherokees refused to emigrate. They waited and watched as the federal government established military posts, mustered state militia into federal service, and restrained the governments and citizens of the states from starting an Indian war.

The collision of states’ rights and federal imperatives over treaty obligations, land ownership, and the meaning of sovereignty resulted in the forced relocation of the entire nation of Cherokee Indians. Costly in terms of government expense, human suffering, and public trust, it was a conflict whose lessons were too soon forgotten.

|

| National Park Service, Cherokee removal routes, Trail of Tears National Historic Trail. |

Between May 26 and June 15, 1838, US soldiers rounded up and removed the citizens of the Cherokee Nation from Georgia. To prepare for its eviction of several thousand Cherokees, the army established fourteen removal posts in the state, clearing local woodlands and altering landscapes. Wagons carrying supplies carved permanent ruts in primitive roads while horses and oxen eliminated grasslands. Military campfires smoked through the nights and forges rang through the days, bending iron to the army’s needs. As whites found employment and markets in the military initiative, cash-poor local economies expanded and populations shifted. Cultures changed, whites replaced Cherokees, and towns emerged with new structures and residents.

The removal of Cherokees electrified Georgians’ emotions and transformed the northern portion of the state. Yet, as physical evidence of Georgia’s removal posts disappeared, the story of Cherokee expulsion from the state became muddled in confusion. For more than a century, accounts misstated post names, numbers, and locations as well as the numbers and activities of military companies.2One such example is George Gordon Ward’s The Annals of Upper Georgia Centered in Gilmer County (Nashville: The Parthenon Press, 1965) which misidentifies the companies and captains at Fort Hetzel and the local militia captain, assigns joint command of Cherokee removal to the three US officers who served sequentially, misstates the date removal began, and overstates the number of Cherokees sent from Fort Hetzel, the number removed from Gilmer County, and the number sent to Indian Territory. Incomplete narratives neglected the involvement of Georgians who supplied the posts, worked as laborers, and transported Cherokee belongings. They overlooked physicians, hospitals, and the precarious health of soldiers. They omitted the participation of Cherokees who earned government money by selling forage to the posts, translating for the military, or driving wagons to the Tennessee holding camps. They obscured the federal government’s protection of Cherokees in the months before removal and neglected the attention to discipline in the forts. They confused local militias with federalized troops and conflated the rapid expulsion of Cherokees from Georgia with their long summer of Tennessee internment.3Two recent studies provide useful correctives for two removal posts: Stephen Neal Dennis, A Proud Little Town: LaFayette, Georgia 1835–1885 (LaFayette, GA: Walker County Governing Authority, 2010), 191–313; John W. Latty, Carrying Off the Cherokee: History of Buffington’s Company, Georgia Mounted Militia (published by author, 2011). It is a pleasure to acknowledge the uncommon generosity of both authors and recognize Stephen Neal Dennis’s summaries and expert guidance through military records in the National Archives.

Inadequate documentation of the removal process led to simplified and sentimental accounts of villainous soldiers, helpless or hostile Cherokees, and greedy Georgia bystanders. Recent research into the details of Cherokee removal from Georgia reveals a more complex process, identifies participants at each post, documents their roles and activities, and establishes a calendar of events. Such new information neither absolves the federal government of its treachery in obtaining a removal treaty, dismisses the criminal aggression of individual Georgians, nor disregards the extraordinary loss the Cherokees experienced. Rather, the records provide substance and texture to a singular moment in history that serves as historical corrective and cautionary tale. The removal of the Cherokee Nation illuminates the consequences of strident disputes over states’ rights, federal authority, and the place of non-Americans in American society. The military records highlight the failure of Congress to provide adequate funds for an enormous and unnecessary military initiative. They document extensive preparations for the roundup of Cherokees and inadequate organization for their actual removal. Deep within the conflicts that wove and unraveled public policy, individual lives and places were forever changed.

As part of the emerging narrative, the story of Fort Hetzel in Ellijay serves as a microcosm of the removal initiative. The story begins with Ellijay’s significance to the Cherokees and to those who removed them.

Ellijay

|

| Location of Ellijay, Georgia, 2012. |

The Cherokee phrase elatse yi means green earth, suggesting that Ellijay promised bountiful resources to the Cherokees who settled there. In the eighteenth century more than one settlement bore the name, hindering efforts to determine when Cherokees established Ellijay in present-day Georgia. The town name appears on eighteenth-century maps in four different locations.4John Mitchell’s 1775 map, reprinted in part by John Swanton for the Bureau of American Ethnology, shows Ellijay north of Kittuwha, the Cherokee mother town in present-day North Carolina: "The Southeastern Part of the Present United States from the Mitchell Map of 1755," Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 73, Plate 6, back papers (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1954). James Mooney identifies four such towns, one in South Carolina on the Keowee River, one in North Carolina on Ellijay Creek of the Little Tennessee River, a third in Tennessee on Ellejoy Creek of Little River, and the fourth in Gilmer County, Georgia: James Mooney’s History, Myths, and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokees (Asheville, NC: Historical Images, Bright Mountain Books, 1992), 517. See also The Payne-Butrick Papers, ed. William L. Anderson, Jane L. Brown, and Anne F. Rogers, vol. 2 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010), 224. Francis Varnod, "A True and Exact Account of the Number and Names of All the Towns Belonging to the Cherrikee Nation," in Peter H. Wood, Gregory A. Waselkov, and M. Thomas Hatley, eds., Powhatan’s Mantle: Indians in the Colonial Southeast (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989), 62.

Adding to the confusion of early maps, eighteenth-century textual references do not clarify the time or place of Ellijay’s settlement. A 1721 census of Cherokee towns included "Elojay, Little" but did not specify a location.5Varnod, 62. In 1725 British trade emissary Colonel George Chicken stayed overnight in "Elejoy"about two miles from the Cherokee Middle Towns in present-day North Carolina.6"Journal of Colonel George Chicken’s Mission from Charleston, S.C. to the Cherokees, 1726," in Newton D. Mereness, ed., Travels in the American Colonies (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1916), 110–11, 126. The British expedition of Captain Christopher French may have gone through the same settlement visited by Chicken (but now called "Allijoy") as soldiers destroyed the Middle Towns in the 1760s.7Christopher French, "An Account of the Towns in the Cherokee Country with Their Strengths and Distance," in Journal of Cherokee Studies 2 (Summer 1977): 297; Christopher Gadsden, "A Particular Scheme of the Transactions of Each Day…from the 7th of June…to the 4th of July When They are Supposed to Return to the Dividings," Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. In the 1770s William Bartram’s list of forty-three Cherokee towns noted "Allagae" as a settlement located on "the waters of other rivers," those he had not traversed.8Bartram listed the Tennessee, Savannah, Tugalu, and Flint Rivers: Gregory A. Waselkov and Kathryn E. Holland Braund, eds., William Bartram on the Southeastern Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990), 88. See also Betty Anderson Smith, "Distribution of Eighteenth Century Cherokee Settlements," in The Cherokee Nation: A Troubled History, ed. Duane King (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1979), 46–60.

In the final years of the American Revolution a series of incursions against the Cherokees has tentatively linked Ellijay to a Georgia location. On July 26, 1782 Tennessee Colonel John Sevier took vengeance on Cherokees by destroying four towns in Georgia including Etowah, Vann’s Town, Coosawattee, and Oostanaula. Although Sevier is occasionally credited with the destruction of Ellijay as well, he left no journal of his expedition. Compounding the uncertainty, records collected closest to the events do not mention Ellijay as among or even proximate to the Georgia towns that Sevier attacked.9See J. G. M. Ramsey, The Annals of Tennessee to the End of the Eighteenth Century (1853. Reprint. Johnson City, TN: The Overmountain Press, 1999), 270–73. By the final decade of the 1700s, however, documents reveal that Ellijay now stood within the boundaries claimed by Georgia.10An unpublished history of the family of Samuel Smith mentions his visit to Ellijay in Georgia in the 1780s: "Something About Some Smiths: An Account of Part of the Samuel Smith Family Dating from 1730 and Ending 1969," 9. I am grateful to Jeff Bishop for providing me with a copy of this family history. Ellijay’s rebirth in different locations over a century of destruction and contraction points to its significance to the Cherokees as a name, place, and memory. It is likely that the descendants of Cherokees from earlier settlements called Ellijay relocated, finally, to present-day Georgia.

|

| Geological Map of Ellijay, Georgia and the Cohutta and Blue Ridge Mountains, 2012. Topographical data from the USGS. |

The significance of Ellijay to the story of removal from Georgia emerges in part from geography. In each of its elusive locations Ellijay was a mountain town. Just fourteen miles from the North Carolina line, Georgia’s Ellijay lies in an elevated valley south of two mountain ranges, the Blue Ridge and the Cohuttas. Peaks of two to four thousand feet arc skyward around and beyond the town. In the Blue Ridge to the northeast Turniptown, Rich, and Wolfpen Mountains rise some four thousand feet while the eastern Owltown and Walnut Mountains ascend twenty-one to twenty-six hundred feet. From the Cohuttas north and west of Ellijay, summits called Douglas, Demps and Turkey Mountains reach elevations of up to twenty-five hundred feet. Talona Mountain to the south is approximately two thousand feet high. Such enduring and demanding landforms shaped the lives of Cherokees who lived among them and secluded them, initially, from white settlement. Mountain Cherokees were the least familiar and most discomfiting to Georgians.

The region’s mountains and their numerous waterways restricted the availability of settlement areas for the Cherokees. The Ellijay River originates in northern peaks and descends rapidly for fifteen miles into the middle of the town bearing its name. The Cartecay River rushes from headwaters in the Blue Ridge on a northwest course of some fourteen miles to reach the settlement. The two rivers unite in Ellijay to form the Coosawattee that flows swiftly southwest toward Coosawattee Town, New Echota, and the heart of the Cherokee settlements in Georgia. Dozens of tributaries flow into these waterways, reshaping and sectioning the landscape. In the 1800s hundreds of Cherokees lived along both rivers and their tributaries, in homes and on farms thinly spread in narrow valleys. The mountain towns remained small, which further isolated these Cherokee citizens from the incursions of white trade, mission work, or the mission schools subsidized by the federal government.

The shoals and falls of the Ellijay and Cartecay Rivers testify to the area’s mountainous topography that limited the development of roads that would later be essential to removal. Georgia’s 1832 survey of Cherokee lands indicates a single road parallel to the Ellijay River on its west side. Occasionally crossing the river, the road ran north to Tennessee and south to the Talking Rock settlement on the Federal Road. A second road (unnoted on the 1832 survey) linked Ellijay to North Carolina. In 1834 a third road was established as a mail route to the town of Dahlonega to the southeast. In the spring of 1838 the military opened a fourth road to connect Ellijay to the Federal Road at Coosawattee Town to the west.11Cherokee County Section 2, District 11, District Plats of Survey, Survey Records, Surveyor General, RG 3-3-24, Georgia Department Archives and History (hereafter cited as GDAH); James B. Henson advertisement, Western Herald, March 21, 1834, and Report of Mail Routes, The Western Herald, April 18, 1834; James J. Field to A. R. Hetzel, 27 March 1838, RG 92, Entry 352, Box 3, National Archives (hereafter cited as NA). The restricted and difficult travel into and out of the mountain communities reinforced the seclusion of mountain Cherokees and reinforced a presumption of their hostility.

|

| Marion R. Hemperly, Map of Indian trails in Georgia before removal, Office of Indian Heritage, 1979. |

Ellijay’s topography contributed to the distinctions that set mountain Natives apart from all others. Among the combined 415 Cherokees living on the Ellijay and Cartecay Rivers, only two had white ancestry. The near-absence of white ancestry among mountain Cherokees suggests that they continued to speak their Native language and maintain traditional Cherokee gender roles, economies, and beliefs. Records show that they farmed smaller tracts, produced little surplus and seldom accumulated wealth.12See William G. McLoughlin and Walter H. Conser, Jr., "The Cherokee Censuses of 1809, 1825, and 1835," in William G. McLoughlin, Walter H. Conser, Jr., and Virginia Duffy McLoughlin, The Cherokee Ghost Dance: Essays on the Southeastern Indians, 1789–1861 (Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 1984), 215–250. With less arable land than elsewhere in the Cherokee Nation in Georgia, the thirty-seven Cherokee families on the Ellijay River cultivated a total of fewer than four hundred acres. Similarly, the twenty-three Cherokee households on the Cartecay River farmed fewer than three hundred acres. Farm size on the two rivers ranged from one acre (one household on the Ellijay) to eighty acres (one household on the Cartecay). No Cherokees on either river owned slaves, and none raised any crop but corn.13 "1835 Cherokee Census," Monograph Two (Park Hill, Ok: Trail of Tears Association Oklahoma Chapter, 2002), 41–42.

Restricted arability, small farms, and monoculture limited the economic development considered a hallmark of American civilization, supporting a stereotype of mountain Cherokees as unprogressive and, therefore, unable or unwilling to utilize land properly. Their language, physiology, and habits made them foreign to American citizens. Familiar to white Americans as the mountain Indians, they were the most conservative of the Cherokee Nation in Georgia, the most opposed to removal, and for those reasons, the most feared.

|

| Anthony Finley, Map of Georgia, 1824, from The New General Atlas, Birmingham Public Library Cartography Collection, digitized by the University of Alabama. |

The population of mountain Cherokees increased in the decades before removal as displaced citizens moved into remaining parts of the Cherokee Nation. In 1824 Chief Charles Hicks instructed Alexander McCoy and Nathan Hicks to identify families whose land had been ceded in recent treaties. "Begin at Ellijay Town," he wrote, and "take names of heads of families who reside perhaps above this old town who removed from ceded land in North Carolina."14Charles Hicks to Alexander McCoy and Nathan Hicks, 1824, MS 2033, Penelope Johnson Allen Collection, Hoskins Special Collections Library, University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Hicks’s letter points to displacement as one source of population increase in mountain towns. It also reveals the coalescing of mountain communities who were considered the most conservative. Such displacement, coalescence, and numerical increase added to rising anxiety among Georgians who impatiently and anxiously awaited Indian removal.

Most noted in records of Ellijay is the man called White Path (Nunnatsunega), a distinguished warrior who served with Andrew Jackson in the War of 1812. Like the town of Ellijay, White Path represented the conservative Cherokees who concerned Georgians and the federal government. A resident of Turnip Mine Town near Ellijay, he emerged as the leading spokesman for mountain settlements and, therefore, a figure known and feared by whites. In the 1820s, as Cherokees embraced various "civilizing" reforms of the federal government, White Path used the Ellijay town house to rail against departure from Cherokee traditions. His forceful opposition led to his 1825 exodus from the Cherokee National Council. By 1827 he had garnered enough support to assemble an alternative council in Ellijay with representatives from seven of the eight Cherokee districts. An alarmed missionary fumed that White Path and others were leading a "heathen party" determined to overturn new Cherokee laws and reject the proposed constitutional form of governance.15See Mooney’s History, 113–14; William G. McLoughlin, Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), 191–92, and Cherokees and Missionaries, 1789–1839 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984), 213–38.

Like many Cherokees, White Path ultimately yielded to the new directions taken in the Cherokee Nation. His charismatic resistance, however, had raised concern among white missionaries and other government agents. Ellijay now signified not just a town or a coalition of communities but a spirit of opposition and independence made manifest in White Path. Such significance would lead to the establishment in Ellijay of the first removal post in Georgia outside of military headquarters at New Echota.

|

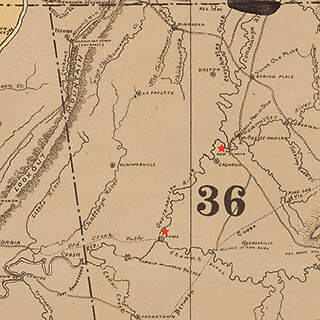

| A map of the second section of that part of Georgia now known as the Cherokee Territory, 1830, Library of Congress Map Collections, 82690523. Ellijay, in the 11th District, is not pictured on this map. |

By 1832 Georgia’s drive to expel the Cherokees had led to the state’s extension of sovereignty over the portion of the Cherokee Nation that lay within her claimed borders (1828–1830). Cherokee and American gold diggers were busily working mines across the so-called gold belt of Georgia while the US Army and, subsequently, the Georgia Guard policed mining activities (1830–1835). After President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act (1830), agents worked tirelessly to obtain a removal treaty from the Cherokees. Meanwhile, the state completed its survey and distribution by lottery of the Cherokee Nation’s land in Georgia (1831–1832). Ellijay now lay in the middle of Gilmer County, one of the ten new counties created by the legislature from the Cherokee Nation. In 1834, Ellijay became the Gilmer County seat.16In the same era Cherokees adopted a constitution establishing a republican form of government and a nation-wide judicial system (1827). Having declared their sovereignty and national boundaries the Cherokee Nation challenged Georgia’s actions in two Supreme Court cases (1830, 1832). The court declined to rule in the first case. Although the Cherokees prevailed in the second (Worcester v. Ga.), the federal government’s executive branch refused to enforce the decision.

Following the federal government’s failure to enforce the 1832 Supreme Court decision upholding Cherokee sovereignty, a few mountain Cherokees enrolled for voluntary emigration. Their departure encouraged agents like William Hardin, who optimistically announced to Georgia Governor Wilson Lumpkin "I think Ellijay has fallen." He described the settlement as "one of the largest villages in the upper part of the nation and where the opposition has hitherto been strongest."17William Hardin to Wilson Lumpkin, 29 March 1832, in Mrs. J. E. Hayes, comp., Cherokee Letters, Talks, and Treaties, GDAH, 340. While the emigration of approximately eleven mountain families did not signal the collapse of Cherokee opposition, Hardin was right that attitudes were diverging. A portion of the Cherokee Nation was abandoning the struggle against removal. The departure of Cherokees willing to emigrate underscored the resistance of those who remained, leaving a population that frightened Georgians and helped provoke the federal government into a massive removal buildup.18See Sarah H. Hill, "'To Overawe the Indians and Give Comfort to the Whites:' Preparations for the Removal of the Cherokee Nation from Georgia," Georgia Historical Quarterly 95, no. 4 (Winter 2011): 465–97.

Between the unenforced 1832 Supreme Court decision and the final expulsion of Cherokees in 1838, Georgians and Cherokees came into increasing conflict. The federal government retained responsibility for the protection of Natives while the state government attended to its citizens who won lottery rights to Cherokee land. Georgia law stipulated that lottery winners could take possession of their prizes where no Cherokees remained as occupants but untold numbers of Georgians disregarded the restrictions and appropriated lots.

|

| Cherokee Phoenix, New Echota, Georgia, April 10, 1828, Library of Congress, 97512373. Text from "Atrocious Injustice," May 18, 1833, is available from the Sequoyah Research Center. |

The May 18, 1833 Cherokee Phoenix recounts such an "Atrocious Injustice" in Ellijay where a lottery winner "entered the possession of Ootawlunsta" with loaded pistols and "drove the innocent Indian from his well cultivated field." Since Georgia courts would not accept Cherokee testimony against a Georgian, Cherokees like Ootaw-sa were left "without a home" or recourse to recover it.19"Atrocious Injustice," Cherokee Phoenix, May 18, 1833. See also Stephen Griffeth to George R. Gilmer, 25 February 1838, Georgia’s Virtual Vault, General Name File, Gilmer, George R., GDAH. For a story from the Georgians see "Indian Difficulty," a Western Herald, November 16, 1833 report that Cherokees killed workmen and burned a mill near Ellijay. The egregious behavior of such whites deprived numerous Cherokees of land, household goods, livestock, and personal wealth. In turn, Cherokee losses led to many thousands of post-removal claims for compensation from the federal government. Abuse by unlawful Georgians cost the federal government, colored Cherokee memories, and tarnished the state’s reputation.

In late December 1835 the federal government obtained a removal treaty from the Cherokees by negotiating with men who held neither Cherokee office nor authority. Following Senate ratification, President Jackson signed the treaty on May 23, 1836 and preparations for the removal of the Cherokee Nation began immediately. The president appointed Wilson Lumpkin, former governor and ardent advocate of Indian removal, as one of two commissioners to settle Cherokee claims for property they would have to abandon. Lumpkin set up office at the old Cherokee capital of New Echota in Georgia. From his military headquarters in Tennessee, the commander of Cherokee removal, General John Ellis Wool, directed the construction of storehouses at New Echota for the food and clothing offered to Cherokees in need. The work of the claims commissioners and presence of the distribution centers brought Cherokees from across their Nation to New Echota, necessitating the posting of troops. Within months the Cherokee Nation’s first capital became the largest of Georgia’s removal posts and headquarters for Cherokee removal from Georgia. By 1837 the name had changed to Fort Wool.

|

| Matthew Brady, Portrait of General John E. Wool, Still Picture Records Section, National Archives. |

Between treaty confirmation in May 1836 and the May 1838 deadline for emigration, the federal commanders of Cherokee removal summoned Georgia militia and volunteer companies to muster at New Echota and become federal soldiers for periods ranging from three to twelve months. When the removal deadline arrived, Georgia’s twenty-nine federalized companies were spread across the Cherokee landscape in fourteen military posts. Cherokees and Georgians watched the two-year buildup anxiously, the former hopeful that Chief John Ross could avert their removal and the latter fearful that the troops and military posts were inadequate for their protection.

The future commander at Fort Hetzel, Captain William E. Derrick of Dahlonega, raised the first Georgia company that was federalized for Cherokee removal. A veteran of the War of 1812 (and thus a former ally of White Path), Derrick was in his early fifties when he assembled the Lumpkin County Cavalry, described by one Georgian as "real mountain boys fit for any emergency."20John Shaw to Adj. General, 19 June 1836, RG 94, M567, Roll 131, Entry 12, S-241, NA. In accord with state authorization Derrick raised the company on Jan. 7, 1836: Georgia Military Affairs, Mrs. J. E. Hays, copier and indexer, vol. 8, 1836–1837 (Atlanta: WPA Project 5993, 1940), 47. On November 11, 1836 General Wool directed Derrick to bring the Cavalry to be mustered into federal service. Wool’s orders reveal the investment required for soldiers entering federal service. Privates and non-commissioned officers received "muskets and accouterments" but each commissioned officer had to bring a sword and, if possible, a pistol, as well as a horse, saddle, bridle, halter, saddle blanket, and martingale (tack that controls the horse’s head). Since the Army provided a clothing stipend rather than a uniform, Derrick was to make sure each man was clothed adequately and arrived with a blanket, overcoat, and at least one spur.21John E. Wool to William E. Derrick, 11 November 1836, RG 94, M567, Roll 154, Entry 12, W-138, NA; Wool to Derrick, 14 November 1836, and Thomas C. Lyon to Derrick, 21 November 1836, John E. Wool Papers, Box 52, File 19, Letter Book, July, 1836-April, 1837, New York State Library, NY (hereafter cited as Wool Letter Book, NYSL).

The Lumpkin County Cavalry then began the process of becoming, for the removal period, a US Army company. On Sunday, November 27, 1836 Derrick’s volunteers left Dahlonega for New Echota. Four days later US Major M. M. Payne inspected and mustered them into federal service. The unit consisted of four lieutenants, seven sergeants, five corporals, sixty-five privates, and one musician. Two stewards and a matron subsequently joined them to aid physician J. A. Bresan in the care of sick soldiers.22I am grateful to Stephen Neal Dennis for providing me with information about the composition of Derrick’s company. The composition likely varied from attrition due to illness or dismissal as well as the limited service periods of three or twelve months.

Assuming one of the most challenging responsibilities for the military, Private James J. Field became company quartermaster charged with ordering, distributing, and accounting for all subsistence, supplies, and forage. Field would record every item, whether ordnance, food, medicine, construction material, express message, or packet of fodder, that came into or departed from his post once the company reached Ellijay. The quartermaster records provide a detailed calendar of the process of developing and maintaining a military post. Additionally, they document the financial cost to the federal government of its determination to remove the Cherokee Nation.

Derrick remained at New Echota until October 1837, serving intermittently as post commander. During his eleven months at the developing facility, he participated in activities common to all military posts. He trained soldiers, maintained order, supervised the transport of government funds, oversaw construction and repair, and resolved conflicts. In their first weeks of federal service Derrick’s men constructed New Echota’s first officers’ quarters, parade grounds, guardhouses, stables, and barracks, the last of which were "erected at but a trifling cost to the department."23A. R. Hetzel to T. Crim, 5 January 1837, RG 92, Entry 350, Box 2, Vol. 1, Hetzel Letter Book, NA, 148; John E. Wool Order 23, 23 January 1837, RG 94, Entry 44, Vol. 13, 569, NA. Such activity provided useful training for the subsequent work at Fort Hetzel.

|

| Mountain Cherokee (untitled sketch). Ink drawing in the diary of Lt. John Wolcott Phelps, 1838, Tebeau-Field Library of Florida History and the Florida Historical Society, Cocoa, Florida. |

Derrick also witnessed the human cost that was unique to the military removal of the Cherokee Nation. He was at New Echota while the claims commissioners interviewed Cherokees who sought compensation. He saw, and perhaps knew, the agents hired by enterprising Cherokees and missionaries to contest the valuations of their property. He encountered Cherokee families seeking the food and clothing rations distributed to those in need. The aggression of hostile Georgians became his problem when Wool ordered him to investigate Cherokee complaints of property seizure, encroachment, theft, assault, and murder.24John E. Wool to William E. Derrick, 25 March 1837, Wool Letter Book, NYSL, 340; Wool to Derrick, 21 May 1837, RG 94, Entry 12, M567, Roll 154, W-214, NA. Officers like Derrick were meant to restrain but not antagonize Georgians, protect Cherokees but urge them to emigrate, and maintain peace among all parties. It was a position requiring equal measures of diplomacy and discipline, judgment and reason. It inevitably earned the resentment of both groups.

In late March 1837 Derrick engaged in a roundup of Natives when Wool ordered him to Coosawattee Town to seize Creeks who had sought refuge among the Cherokees. In an apparent expansion of military authority, Wool authorized Derrick to arrest and deport Cherokees who concealed or aided the Creeks or failed to assist him in their capture.25Wool Order 11, 22 March 1837, RG 92, Entry 357, Box 6, NA; John E. Wool to William E. Derrick, 25 and 28 March 1837, Wool Letter Book, NYSL, 339–40, 346–47. P. M. Wear to William E. Derrick, 30 March 1837, Wool Letter Book, NYSL, 340; H. B. Shaw to Joseph Byrd, 10 April 1837, RG 94, Entry 12, Roll 154, W-179, NA. Big Frog Mountain is north of Ellijay. After collecting just thirty-three Creeks (a number so small it earned Wool’s reproach), Derrick departed for "Frog Mountain in Gilmore County" to track down a reported two hundred more who had fled into the mountains.26P. M. Wear to William E. Derrick, 30 March 1837, Wool Letter Book, NYSL, 340; H. B. Shaw to Joseph Byrd, 10 April 1837, RG 94, Entry 12, Roll 154, W-179, NA. Big Frog Mountain is north of Ellijay. The assignment was Derrick’s first pursuit of Natives hiding in the Gilmer County wilderness. He would return to Frog Mountain the following year to complete his removal of Cherokees.

Federal troops served as both threat and guardian for the Cherokees. Called into service for the purpose of removing Indians, they were required to protect them until the treaty deadline. In late April and again in early May 1837 General Wool ordered detachments to investigate claims of illegal aggression against Cherokees in the mountains. He authorized soldiers to eject the intruders with a warning that if they again "interfered with the Indian on his property" they would be expelled from Gilmer County.27Charles Hoskins payment to Captain Buffington, May 16, 1837, Voucher 3, Subvoucher 58, Sub-subvouchers 15 and 24, A. R. Hetzel Account 2340, Box 1141, RG 217, Entry 712, NA (hereafter cited as Hetzel account number, Box number, NA). Evicting whites from the homes and farms of Walkingstick, Cryer, White Path, Hatchet, Christy, Alsey, Foster, Cricket, and Tonoe, the troops restored the Cherokee owners to their property. In addition, they obtained restitution from the whites who had stolen cattle from Taulater and Rachel Morris.28John W. Latty, Carrying Off the Cherokee: History of Buffington’s Company, Georgia Mounted Militia (Published by the author, 2011), 68. Wool’s insistence on protecting Cherokees and their belongings antagonized Georgians who disregarded state and federal laws. When Wool relinquished command in July 1837, his successor Colonel William Lindsay encountered similar offenses and comparable complaints that were increased by Georgians’ growing fear that the Cherokees were preparing for war.29Wool left to face court martial charges of preferential treatment of Cherokees in Alabama. Winfield Scott presided over and William Lindsay served on the court martial that exonerated Wool: "Proceedings of a Court of Inquiry Relating to Transactions of Brevet Brigadier General John E. Wool," American State Papers: Military Affairs 7: 533–71.

Anticipating a Cherokee uprising and unwilling to rely on federal troops, Governor William Schley authorized the so-called Cherokee counties to raise companies for the defense of citizens and removal of Indians. Removal, however, was a federal rather than a state responsibility. Schley justified his decision to the frustrated Secretary of War by insisting that "the savages" could act in concert and "murder thousands of men, women and children" before federal troops could assemble. White Path, according to the governor, had warned the Gilmer County Georgians "that the Indians would cut the throats of every white person in the county" before they were expelled. Within days of Schley’s assertion three newspapers repeated the rumor, heightening public fear.30William Schley to Joel Poinsett, 2 October 1837, RG 107, M221, Roll 118, G 503, NA; "Cherokee Troops," The Federal Union, October 3, 1837 (Milledgeville) notes that the same story was reported in the Southern Banner (Athens) and the Miner’s Record (Dahlonega).

As the governor defended himself and anxious Georgians passed along the allegations, Colonel Lindsay ordered Derrick to Ellijay to select a site "in the neighborhood of Jones’s" suitable for a military post.31Lindsay Order 15, 5 October 1837, RG 92, Entry 356, Box 6, NA.

Fort Hetzel

Lindsay’s decision to locate the fort in Ellijay directly confronted escalating tensions among Georgians and Cherokees. With previous war service and nearly eleven months of duty at Fort Wool, Derrick was the most experienced officer among the federalized troops in Georgia. He was surely considered the most competent to reassure the whites of Gilmer County, protect the Cherokees until the treaty deadline, and complete their peaceful removal immediately thereafter. In addition, his pursuit of Creek refugees in the Gilmer County mountains the previous year provided an advantageous familiarity with the area and, perhaps, the Cherokee and white occupants as well.

Derrick received his orders on Thursday, October 5, 1837 and led his mounted company to Ellijay soon after. The command to locate the post "in the neighborhood of Jones’s" took them to the Cartecay River near its junction with the Ellijay. Samuel Jones, like Derrick and the Lumpkin County Cavalry, came from Dahlonega where he had served as the county’s first sheriff. After moving with his family to Ellijay around 1835, he was elected sheriff and appointed road commissioner and Inferior Court justice.32Acts of the General Assembly, November–December, 1836, vol. 1, sequential number 143, p. 243; Mary B. Warren and Eve B. Weeks, eds., Whites Among the Cherokees, Georgia, 1828–1838 (Athens, GA: Heritage Papers, 1987), 199. His position as enforcer and adjudicator of laws in Gilmer County made him familiar to federal officers like Lindsay and to Georgians like Derrick.

The process of siting and naming the Ellijay post highlights the lack of direction given to post commanders and their resulting autonomy to make certain kinds of decisions. Rather than determining the precise location for his post Derrick called on a quartermaster at the New Echota garrison to select a suitable site. Colonel Abraham Cox subsequently wrote that he had difficulty finding "level ground sufficient to set the encampment in." Although he thought the site provided the necessary access to wood, water, and forage, Cox considered it "objectionable from a military point of view." The uneven terrain and scarcity of roads were likely causes of concern, particularly since the courthouse and town buildings stood a mile distant on the other side of the Ellijay River. Having given Cox responsibility for selecting the site, Derrick then invited him to provide its name. Cox decided to call the post Fort Hetzel in tribute to his supervisor Abner Reviere Hetzel, who was stationed in Tennessee as the acting quartermaster for the Cherokee removal army.33Cox had arrived in Gilmer County to determine the availability and cost of forage when Derrick called on him to locate the post. The plan for forts has not been found. A. R. Hetzel to Major Cross, 7 October 1837, RG 92, Entry 350, Box 2, 85, NA; A. Cox to Hetzel, 21 October 1837, RG 92, Entry 352, Box 3, NA. The area Cox selected for the post is now East Ellijay. After choosing the site and name, Cox returned to New Echota.

|

| Fort Marr Blockhouse, Benton, Tennessee, March 2009. This is the last surviving remnant of a Tennessee removal-era fort. |

Derrick’s men then repeated the kind of work they had undertaken in their early months of service at New Echota. On the ‘somewhat objectionable’ military site they erected barracks, officers’ quarters, storage buildings, stables, blockhouses, a hospital, and a coal-burning forge. Construction continued through March 1838 when they completed the picket or stockade around the fort by hanging its gate.34James J. Field payment to Luther Wallis, March 23, 1838, Voucher 18, Subvoucher 25, Sub-subvoucher 6, Hetzel 3933, Box 1194, NA. The records of their work illuminate the process undertaken by the federal government to prepare for the removal of the Cherokee Nation. Each day Fort Hetzel quartermaster James J. Field issued pay vouchers to soldiers and citizens who built, supplied, and maintained the post. In addition to service pay soldiers earned extra money constructing the picket and guard house, assisting in the quartermaster’s office, distributing forage, delivering express messages, shoeing horses, and burning "coal kill," the residue of coal fires at the forge.

Georgians, including neighboring Samuel Jones, earned government money by transporting supplies, providing forage, making furniture (including bunks for the barracks and the gate to the fort), driving horse and ox teams, housing express riders, carrying messages, and repairing wagons. Local storekeepers like Coke Ellington sold items to "the U. S." ranging from blankets and sealing wax to blank books and frying pans.35A. R. Hetzel payment to William Johnston, Nov. 23, 1837, Voucher 7, Subvoucher 34, Hetzel 3507, Box 1102; James J. Field payment to Benjamin Griffith, Dec. 7–8, 1837, Voucher 16, Subvoucher 30, Sub-subvoucher 1, and to S. W. Wood, Dec. 31, 1837, Voucher 16, Subvoucher 30, Sub-subvoucher 4, both in Hetzel 3507, Box 1182; Field payment to Joel Abney, Feb. 5, 1838, Voucher 10, Subvoucher 15, Sub-subvoucher 1, to George Brock, Feb. 20, 1838, Voucher 10, Subvoucher 15, Sub-subvoucher 9, to J. Johnston, Feb. 22, 1838, Voucher 10, Subvoucher 15, Sub-subvoucher 11, and Extra Duty Pay Roll and Muster Roll, Feb. 1838, Voucher 10, Subvoucher 15, Sub-subvoucher 16, all in Hetzel 3933, Box 1193, all in NA; Ward, Annals of Upper Georgia, 583–87; Lawrence L. Stanley, A Little History of Gilmer County (Published by the author, 1975), 10–12. Civilian support proved essential to the construction and maintenance of the post and, therefore, to removal itself. Establishing a fort in a mountainous area with few roads and little commerce engaged Georgia’s citizens, changed the face of the countryside, and boosted local economies. The impact of removal on the local economy as well as that of the national war industry can hardly be overstated.

In late March, Quartermaster Field reported that he had opened a road (doubtless by expanding an existing trail) between Fort Hetzel and Coosawattee Town on the Federal Road in order to shorten the delivery of goods.36James J. Field to A. R. Hetzel, 27 March 1838, RG 92, Entry 352, Box 3, NA. The only wagon way cut explicitly for Cherokee removal from Georgia, the road came into near-daily use. The supplies that arrived from Fort Cass and Fort Wool from October 1837 through July 1838 document the scope of the Cherokee removal process by detailing the goods and services required for the military posts. Fort Hetzel received flour, pork, coffee, and sugar, plus vinegar and salt for preservatives. Food packed in 200-pound barrels was placed in storehouses until distribution. Each day soldiers drew rations of flour to make their own bread. Lacking vegetables as well as beef, subsistence at Fort Hetzel barely met the military standard for diet.37The daily ration per soldier was eighteen ounces of flour for bread, twenty ounces of beef, and portions of vinegar and salt. The 1832 regulation substituted four ounces of coffee and one of sugar for the issue of spirits: Louis C. Wilson, "Feeding Our Soldiers," The Quartermaster Review, May–June, 1928, www.qmfound.com; Luther D. Hanson, Quartermaster Museum, personal communication, 8 March 2012. More than eight hundred pounds of candles and six hundred of soap completed the list of subsistence goods. Limited in variety, the supplies arrived in sufficient quantities to necessitate periodic repair of the fort’s storage facilities.

While shipments frequently included construction materials, ordnance, and hospital supplies, the deliveries of subsistence exceeded all others in quantity and frequency. A single wagon arrived in October with twelve barrels containing more than two thousand pounds of flour that apparently lasted through the following month. In December the amount of flour jumped to sixty barrels or twelve thousand pounds, followed by January deliveries that exceeded twenty-five thousand pounds. Although subsequent quantities diminished, flour continued to arrive until the completion of Cherokee removal. In March, as an infantry company joined the post, the men received some six hundred pounds of rice as well, surely a welcome relief.38See for example A. R. Hetzel payment to James W. Erwin, Oct. 20, 1837, Voucher 1, Subvoucher 27, Hetzel 3507, Box 1182; A. Cox payment to F. C. Peterson, Dec. 3, 1837, Voucher 16, Subvoucher 24, to J. A. Hutton, Dec. 4, 1837, Voucher 16, Subvoucher 1, and to F. C. Peterson, Dec. 18, 1837, Voucher 16, Subvoucher 11, all in Hetzel 3507, Box 1181; Hetzel payment to Jonathan Thomas, Voucher 1, Subvoucher 8, Cox payment to F. C. Peterson, Jan. 9, 1838, Voucher 3, Subvoucher 1, Hetzel payment to Elijah Shipley, Jan. 10, 1838, Voucher 1, Subvoucher 9, and to Silas Morgan, Jan. 10, 1838, Voucher 1, Subvoucher 10, all in Hetzel 3933, Box 1192; Hetzel payment to Richard McFall and Henry Richards, Jan. 17, 1838, Voucher 1, Subvoucher 15, to Thomas McCarty, Jan. 17, 1838, Voucher 1, Subvoucher 16, and to Robert Smith, Jan. 18, 1838, Voucher 1, Subvoucher 21, all in Hetzel 6814, Box 1260; Hetzel payment to Jesse Billingsley, March 31, 1838, Voucher 16, Subvoucher 106, Hetzel 3933, Box 1292, all in NA.

Other wagons brought more than seven thousand pounds of bacon, including one shipment of sides, joints, and "joles" (jowels) that arrived just days before the removal deadline. In conformity to the army’s 1832 mandate to distribute sugar and coffee in place of its customary issue of whiskey rations, the post received as a substitute more than two thousand pounds of sugar and nineteen hundred pounds of coffee.39Wilson, "Feeding Our Soldiers," 1–9. For pork see A. R. Hetzel payment to William Johnston, Nov. 23, 1837, Voucher 7, Subvoucher 34, Hetzel 3507, Box 1102; Hetzel payment to Robert Smith, March 5, 1838, Voucher 16, Subvoucher 6, to James Walker, March 5, 1838, Voucher 16, Subvoucher 7, and to G. W. Graves, March 13, 1838, Voucher 16, Subvoucher 21, all in Hetzel 3933, Box 1192; Hetzel payment to James Shadle, May 10, 1838, Voucher 44, Hetzel 6814, Box 1262, all in NA. For sugar and/or coffee see A. Cox payments to F. C. Peterson, Dec. 3 and 18, 1837, Voucher 16, Subvoucher 24, and Voucher 3, Subvoucher 1, both in Hetzel 3507, Box 1181; Hetzel payment to James Walker, March 5, 1838, Voucher 16, Subvoucher 7, to Robert Smith, March 31, 1838, Voucher 16, Subvoucher 87, and to Jesse Billingsley, March 31, 1838, all in Voucher 16, Subvoucher 106, Hetzel 3933, Box 1192, all in NA.

In addition to the supplies that came from Fort Cass and Fort Wool, the quartermaster procured thousands of bushels of corn and bundles of fodder from Georgians living near Fort Hetzel. The horses for Derrick’s company and the oxen that hauled materials at the fort required daily rations that provided Georgians as well as occasional Cherokees with a reliable forage market through the entire removal period. Quartermaster Field followed orders to canvass the area to determine the availability of forage and to contract for all he could "before it becomes known that so large a supply will be required." One January order directed the acquisition of seven thousand bushels of corn and "hay or fodder in proportion" at a cost of over five thousand dollars.40A. R. Hetzel to J. J. Field, 25 January 1838, RG 92, Entry 350, Box 2, Hetzel Letter Book, vol. 2, 107–08, NA. By the first week of May, Field had purchased all the available forage in the area. His department was in debt and he was "much harassed by government creditors" who had become "loud and clamorous in their demands upon him for payment."41V. M. Campbell to A. R. Hetzel, 16 April 1838, RG 92, Entry 352, Box 3, NA. Insufficient and delayed funding for the quartermaster service at the Georgia posts highlights the inadequacies of the arrangements for Cherokee removal.

|

| J. C. McRae, engraver, and J. Kelly, printer, Portrait of George R. Gilmer, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, New York Public Library. |

While the federal government’s military preparations proceeded, the state launched its own initiative. In late January 1838 Jonathan O. Price complied with the most recent state order to raise a local company to protect Georgia citizens and remove the Indians. Describing Gilmer County residents as "much alarmed," Price warned recently-elected Governor George R. Gilmer that the "Indians say they would rather fight than go, and Creeks have joined them." He solicited arms and ammunition, imploring Gilmer to "call the company into camps to prepare a fort."42Hayes, comp., Letters, Talks, Treaties, GDAH, 659. Assembled by state rather than federal order, Price’s mounted company was never federalized and did not participate in the removal of Cherokees. The sixty-four Gilmer County men served as a home guard under a parallel military command. Regulation of such companies fell beyond federal control, discomfiting the federal officers and increasing tension between state and federal authorities. Eager to expel Indians, the home guards seldom understood that removal was not their prerogative. Their subsequent pension and bounty claims for service in the "Cherokee Wars" contributed to the confusion that has long characterized Cherokee removal history.

The heated rhetoric of Gilmer County whites points to a rising panic that led to assertions of Cherokee hostility and a demand for military intervention by the state. Anticipating that the "blood of our wives and children will be spilt in grate quantitys," William Cole claimed the "Indians say they are not going" and "the whites have to leave." Benjamin Griffith described increasingly "bold and saucy" Cherokees who were supposedly stashing corn in the mountains in preparation for a siege. Jonathan Price passed along rumors that "an old Indian living in the mountains" had assembled a magazine and that Cherokees were supplying fugitive Creeks. He asserted that the number of mountain Cherokees increased daily as refugees arrived from other parts of the Nation. All agreed that the Cherokees were making no preparations for removal and many construed Cherokee impassiveness as a prelude to war.43William Cole to George Gilmer, 1 March 1838, RG 1-1-5, Box 19; B. Griffith to George Gilmer, 27 February 1838 in Hayes, comp., Letters, Talks, Treaties, 680; Jno. Price to George Gilmer, 5 May 1838, RG 1-1-5, Box 19, all in GDAH.

Derrick repeatedly investigated reports of hostility on both sides, with the assistance of Cherokee interpreters such as John Tucker and John and David Kell. As he continued to uphold Cherokee rights, citizens protested to the governor that Derrick was protecting Cherokees and making decisions based on "testimony wholly Indian."44James J. Field payment to John Tucker, Jan. 30, 1838, Voucher 3, Subvoucher 15, Sub-subvoucher 4, Hetzel 3933, Box 1192; Field payment to John Kill, Feb. 10, 1838, Voucher 10, Subvoucher 15, Sub-subvoucher 7, and to David Kell, Feb. 20, 1838, Voucher 10, Subvoucher 15, Sub-subvoucher 10, both in Hetzel 3933, Box 1193, all in NA; A. J. Hansell to George Gilmer, 24 February 1838, Georgia’s Virtual Vault, General Name File, Hansell, A. J., GDAH. Immersed in fear and rumor, Gilmer County whites took little comfort from the presence of Derrick’s company and the fortified post in their midst. The arrival in mid-March of Captain H. I. Dodson’s Tennessee unit of eighty infantrymen did not diminish their escalating concern. William Cole complained that troops were stationed "at the most inconvenient they could have chosen," an echo of Colonel Abraham Cox’s assessment when he selected the post’s location.45Dodson’s was the only non-Georgia company that served in the removal of the Cherokee Nation from Georgia. A. R. Hetzel to John J. Field, 14 March 1838, RG 92, Entry 350, Box 2, Hetzel Letter Book, 214; Hetzel payment to Hiram Grimmett, March 30, 1838, Voucher 16, Subvoucher 78, Hetzel 3933, Box 1192, both in NA. As removal approached the citizens "were much alarmed and forted [stockaded] in several places." They frequently called on Derrick as well as Jonathan Price for protection that proved unnecessary.46William E. Derrick to Abraham Eustis, 4 June 1838, RG 393, M1475, Roll 1, frames 0539–40, NA.

|

| Matthew Brady, Portrait of Winfield Scott, circa 1861, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. |

In April General Winfield Scott replaced Lindsay as commander of the Cherokee removal army and promptly divided the Cherokee Nation into three military districts. Eight of the fourteen posts in Georgia lay in the Middle Military District under the command of Militia General Charles R. Floyd. Six posts, including Fort Hetzel, were assigned to the Eastern District headquartered in North Carolina and commanded by U. S. General Abraham Eustis. A fifteenth post, planned for the state’s northwestern corner as part of the Western District, was never established.

On May 17 an army report listed twenty-three removal posts in four states. The tally identified Fort Hetzel as fifty-seven miles from Fort Cass with one mounted and one infantry company totaling 150 federalized troops under Derrick’s command. Beginning on May 20, Derrick sent detachments to the surrounding Cherokee communities to post or read General Scott’s order for peaceful surrender. On May 26, pursuant to orders that coordinated the military expeditions in Georgia, the men of Fort Hetzel began rounding up the mountain Cherokees.47"Volunteer Posts and Stations of the Army of the Cherokee Nation," 17 May 1838, RG 393, M1475, Roll 1, frames 256–57; James J. Field payment to Jake (Jesse?) Ratley, May 21, 1838, Voucher 131, Subvoucher 4, Sub-subvoucher 11, and Express Packet, Hetzel 6814, Box 1265, all in NA. The onset of removal from Georgia was delayed until General Charles R. Floyd arrived to take command of the Middle Military District.

Removal

|

| Cherokee basket and lid, double woven of river cane and dyed with walnut, early 1800s, Georgia, Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. |

Just as the warnings of impending arrest had not prepared Cherokees for the events of May 26, their notorious aversion to removal had not prepared the military for their resistance. "They run in every instance where they have the lest [sic] opportunity," Derrick acknowledged with surprise. To entice surrender from those who evaded capture he had "broken their familys in such a way that I think the outstanding numbers will come in," a strategy that effectively traumatized the prisoners. Derrick’s comment that he lacked "sufficient numbers to guard them scattered as they were" reveals the roundup procedure. Soldiers separated into detachments to collect prisoners in small groups and remained with them until every available soldier stood guard over a household or neighborhood.48William E. Derrick to W. S. Worth, 28 May 1838, RG 393, M1475, Roll 1, frames 0408–09, NA.

The haste of the roundup undermined the federal government’s plan to allow Cherokees to gather their possessions as they were arrested. Derrick’s men captured Cherokees as they were fleeing empty-handed into the mountains. Rather than escorting captives back home to collect their belongings, soldiers brought them directly to Fort Hetzel. Derrick explained that his men "could not bring off their property at the time the news would have spread like litning." With speed and stealth the soldiers gathered "425 or perhaps 450" mountain Cherokees in two days, "as many as I can manage with the force that I command."49Ibid. Derrick’s brief description, one of the few surviving first-hand reports, sketches the roundup of Cherokees as sudden, intense, and absolute. It was a terrifying moment that entered accounts of Cherokee removal as a description of the entire process.

Derrick’s initial report reveals that two years of anticipating Cherokee removal had not resulted in sufficient military organization. His supervisor, General Abraham Eustis, had not arrived at his command post in North Carolina when the roundup began. Lacking instructions about the disposition of his prisoners, Derrick felt "at a loss to know how to get them to Calhoun [Fort Cass]." He pointed out the difficulty of "getting wagons here" to haul prisoners and their belongings, and emphasized his need for wagons and time "to collect their little plunder" before removing Cherokees from the state.50Ibid. Scott instructed Derrick to send his prisoners "as early as may be consistent with humanity" by using the captured Indian ponies for transportation. On receipt of the order Derrick snapped to a quartermaster that he was "at a loss to know how the Indian horses is to be subsisted" in the absence of forage and grass. The detailed planning that produced a swift and effective roundup had failed to provide for the enormous task of transporting thousands of Cherokees and their belongings from the state of Georgia.51W. J. Worth to William E. Derrick, 29 May 1838, RG 93, M1475, Roll 1, frame 0436, and Derrick to A. R. Hetzel, 1 June 1838, RG 92, Entry 352, Box 3, both in NA.

In addition to the information that the Cherokees had not been permitted to gather their belongings, Derrick’s report exposes another failure in the round up. To induce fugitives to come into the fort he made certain to arrest "the principle headmen in this part of the district," Old Hemp, Young Duck, and Kingfisher. Yet he failed to convey to his men the federal directive to leave White Path’s family alone. Still the leader of the mountain Cherokees, the venerable White Path was in Washington with Chief John Ross trying to negotiate a new treaty and postponement of removal. General Scott had apparently intended to shield the families of the Cherokee negotiators but Derrick acknowledged that one of his lieutenants "did not understand the orders" and mistakenly arrested White Path’s family. Derrick "proposed to the old lady to send them home" but the family refused, choosing instead to remain with the other captives.52William E. Derrick to Abraham Eustis, 4 June 1838, RG 393, M1475, Roll 1, frame 0539, NA. Old Hemp’s name as given does not appear on the 1835 census; Young Duck and Kingfisher lived on Sceare Corn Creek: "1835 Cherokee Census," 40.

|

| Robert Lindeux, The Trail of Tears, 1942, in the Woolaroc Museum, Bartlesville, Oklahoma, from the Granger Collection. |

By the first week of June five hundred prisoners were camped at Fort Hetzel waiting for wagons from Fort Cass. Eustis had arrived at his North Carolina post and assumed command over Derrick and other leaders in the Eastern Military District. Preparing to return to Frog Mountain in pursuit of Cherokee fugitives, Derrick wrote Eustis that "they seem well satisfied now and I don’t apprehend we shall have much trouble to collect them hereafter." Perhaps his perceptions were accurate for ultimately he captured and sent 884 Cherokee prisoners from Fort Hetzel, nearly twice his original estimate and one of the highest numbers of captives from Georgia.53William E. Derrick to Abraham C. Eustis, 4 June 1838, and Derrick to J. H. Simpson, 25 June 1838, both in RG 393, M1471, Roll 1, frames 0539–40 and 0752-54, NA.

Derrick’s letter from Fort Hetzel partially undercuts the allegations of indifferent military discipline at the posts in Georgia. General Scott received information that Derrick had employed unauthorized troops to serve with him, a reference to Captain Jonathan Price’s militia company. In response to Scott’s demand for an explanation Derrick stated that one of his detachments "fell in with Captain Price" while scouting but no military action or service had resulted.54William E. Derrick to Abraham Eustis, 4 June 1838, RG 393, M1475, Roll 1, frame 0539, NA. Years later a member of Derrick’s company testified that he heard Derrick say he wanted Captain Price "to assist him in capturing the Indians:" John W. Griffith to Ebeneezer Fain, 3 February 1857, card file (Griffith, John W.), GDAH. The unidentified report to Scott and quick challenge to Derrick points to previously unnoted attention to the behavior of soldiers at the Georgia posts.

There was, however, an additional question to be resolved. Scott charged Derrick with "treating a Cherokee woman with cruelty," an accusation that provoked his emphatic denial. Asserting "there is not a man in the Cherokee Nation more respected by the Indians than myself" Derrick claimed he had "treated them with that attention and kindness their situation requires." He acknowledged that "one of my men, in taking some prisoners, had to knock down a squaw" but explained that she had struck at the soldier with "a large stone," then tried to take his gun. Believing the soldier to be "a very correct young man" who would "do nothing wrong intentionally," Derrick defended the soldier’s behavior. He immediately "reproved him" and took no further action. "I don’t think the lick was struck amiss at the time," he commented to Eustis. Considering Derrick’s description "a satisfactory explanation of his conduct" Eustis did not pursue the matter.55Abraham Eustis to W. J. Worth, 5 June 1838, RG 393, M1475, Roll 1, frames 0536–37, NA.

Missing from either the charge or defense are details such as Scott’s source of information, the soldier’s general behavior, the victim’s age or condition, the presence or absence of children or elders, force of the soldier’s retaliation, severity of the victim’s injury, or observations by other soldiers or prisoners. In time, such incidents of abuse would become part of the Cherokees’ collective memory of removal from Georgia, a shared recollection exacerbated by the attitudes evident in Derrick’s facile explanation and Eustis’s quick absolution.56Ward’s often-problematic history of Gilmer County includes an unattributed story congruent with Derrick’s report. It reports the arrest of a Cherokee mother whose "violent protestations" in Cherokee could not be understood by the soldiers. Subsequently learning through a translator that her young children had fled to the woods the soldiers took her back to collect the children: Ward, Annals of Upper Georgia, 58.

Between Derrick’s initial roundup of Cherokees on May 26 and the final exodus of captives on June 24, soldiers collected the prisoners’ belongings for transport to Tennessee. Initially hampered by the military’s failure to provide wagons, Derrick earned Scott’s commendation "for your humane effort in attempting to secure the property of the Indians."57W. J. Worth to William E. Derrick, 29 May 1838, RG 393, M1475, Roll 1, frames 0436–37, NA. On May 30 nine wagons left the post "hauling the effects of Cherokee emigrants from Ellijay to the Cherokee Agency" in Tennessee. Two more left on June 10 and a third detachment of seven wagons and four drivers departed on June 12 and arrived at the Agency on June 21. Additional wagons bearing "Cherokee effects" followed in July, August, and September, totaling twenty-five wagons filled with Cherokee possessions, or up to twenty-five thousand pounds of goods. Natives Drowning Bear, John Sanders, and Huckleberry were among the haulers earning $5 per day for each five-horse wagon they drove.58Richard A. Gabriel and Karen S. Metz, "Logistics and Transport," A Short History of War: The Evolution of Warfare and Weapons (Strategic Studies Institute, USAF War College, 1992), http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/gabrmetz/gabr000a.htm; unnumbered vouchers from RG 217, Entry 525, NA, assembled as Cherokee Trail of Tears Primary Sources from the National Archives, Box 266/Acct. 2589M, Box 281/Acct. 3136J and J2, and Box 282/Acct. 3136K, Sequoyah Research Center, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, AR. (hereafter cited as SRC). Gabriel and Metz write that horses replaced oxen as early as the Assyrian Wars when commanders learned that a five-horse wagon team could carry the same weight as a single-ox cart, which was one thousand pounds.

On June 25 Derrick announced that few Cherokees remained in Gilmer County and Georgia citizens no longer felt apprehension.59William E. Derrick to J. H. Simpson, 25 June, 1838, RG 393, M1475, Roll 1, frames 0752–54, NA. The pace of activities at the fort quickly subsided. Quartermaster Field issued pay vouchers to two Georgians who hauled in Cherokee corn, perhaps to forage the mounted company’s horses. He paid Moses Greer to make bunks for the sick soldiers in the post hospital. On July 12 Joseph Holden was paid to auction off all remaining quartermaster stores, a public event that left empty structures on a desolate landscape. The week following the auction Derrick returned with his company to New Echota for dismissal. Col. M. M. Payne, who had mustered his company in the winter of 1836, completed the discharge of all Georgia troops on July 19. Men of the federal removal army in Georgia returned to civilian life, eligible for bounty land for their military service.60James J. Field payments to Franklin Hale and James Hale, June 16 and 17, 1838, Voucher 11, Subvouchers 2 and 3, to Moses Greer, July 2, 1838, Voucher 10, Subvoucher 2, and to Joseph Holden, July 12, 1838, Voucher 10, Subvoucher 5, all in Hetzel 6814, Box 1261; M. M. Payne to R. Anderson, 19 July 1838, RG 393, M1475, Roll 1, frames 1037–38, all in NA.

As the soldiers mustered out of the army, Ellijay citizens fulfilled a remaining obligation of the federal government to compensate Cherokees for their household goods. Samuel Jones, in whose neighborhood Fort Hetzel was placed, was appointed to collect and sell Cherokee belongings left in Gilmer County. He and Jonathan D. Chastain began work on October 1 and finished twenty-seven days later, earning four dollars per day for dispensing with Cherokee possessions. They delivered the sales money to Fort Cass for shipment to the Indian Commissioners in Washington who were responsible for its distribution to the Cherokees.61Unnumbered vouchers from RG 217, Entry 525, NA, Cherokee Trail of Tears Primary Sources, Box 490, SRC. The completion of their work erased remaining evidence of Cherokee occupation in the Georgia mountains.

Captain Jonathan E. Price and his Ellijay militia disbanded in July and spent the next nineteen years trying to collect service pay from the federal government for work they undertook for Governor Gilmer and the state. As part of their efforts they, like many Georgians, increasingly recalled the imperative of their service as a defense against warlike and hostile Cherokees. In 1892 they or their widows were declared eligible for military pensions for service in the "Cherokee disturbances."62William Henry Glasson, History of Military Pension Legislation in the United States(PhD diss., Columbia University, 1900), 64–66. The "disturbances" remain filed under the category "Indian Wars."

|

| J. S. Clark, Former Cherokee landscape, Ellijay, Georgia, December 2006. |

According to local accounts "the severely simple fort" stood until about 1868.63Ward, Annals of Upper Georgia, 56. The sketch provided in Ward’s book "based on careful research by the Author and artist Robert C. Adams" depicts a stockade surrounding one building and omits all other structures known to have been part of the post (guard house, storage houses, stables, hospital, and forge). The sketch thus minimizes the impact the fort’s appearance likely had on Cherokees. Gradually, Fort Hetzel and its role in the removal of the Cherokee Nation from Georgia receded into shadow and silence. In the absence of physical evidence and adequate documentation, the narrative of Cherokee removal from Georgia became sufficiently vague to simplify a complex story and accommodate any historical interpretation. Emerging details reveal its complexities and call for a deeper engagement of a singular historical tragedy. They point to greater ambiguity in the choices available to the Cherokees who found a brief measure of justice in the federal government’s protection of their rights until the removal deadline. They reveal the federal government’s failure to anticipate the scope of the removal initiative, which amplified its human, emotional, and economic costs. They illuminate the development of alternative narratives as Georgians ignored federal prerogatives, capitulated to emotional rhetoric, and sought comfort with arms and aggression. They bring to light the missing names and locations, activities and events, attitudes and motivations that make the history of Cherokee removal from Georgia a living and relevant discourse for the present. It is time to restore the missing pieces and set the record straight.

About the Author

Sarah H. Hill earned her doctorate in American Studies at Emory University and is author of Weaving New Worlds: Southeastern Cherokee Women and their Basketry. Dr. Hill is an independent scholar in Atlanta and is currently writing a book on the removal of the Cherokee Nation from Georgia.

Recommended Resources

Anderson, William L., ed. Cherokee Removal, Before and After. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1991.

Banner, Stuart. How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005.

Garrison, Tim Alan. The Legal Ideology of Removal: The Southern Judiciary and the Sovereignty of Native American Nations. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2002.

Hill, Sarah H. "'To Overawe the Indians and Give Comfort to the Whites:' Preparations for the Removal of the Cherokee Nation from Georgia," Georgia Historical Quarterly 95, no. 4 (Winter 2011): 465–97.

———. "East is East and West is West: Cherokee Women After Removal," Journal of Cherokee Studies 20 (1999).

Norgren, Jill. The Cherokee Cases: The Confrontation of Law and Politics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1996.

Littlefield, Daniel F., and James W. Parins, Encyclopedia of American Indian Removal. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Imprint of ABC-CLIO, 2011.

McLoughlin, William G. Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Perdue, Theda and Michael D. Green, eds. The Cherokee Removal: A Brief History with Documents. Boston: St. Martin's Press, 2005.

Links

Garrison, Tim Alan. "Cherokee Removal." In The New Georgia Encyclopedia.

http://www.newgeorgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-2722&hl=y.

———. "Worcester v. Georgia (1832)." In The New Georgia Encyclopedia.

http://www.newgeorgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-2720.

Similar Publications

| 1. | The unique 1802 Compact between Georgia and the federal government settled Georgia’s claim to its western land beyond the Chattahoochee River in return for a pledge to extinguish Indian title to lands within the state’s claimed boundaries. The Cherokee Nation’s claim to an overlapping portion was guaranteed by a series of treaties with the federal government. |

|---|---|

| 2. | One such example is George Gordon Ward’s The Annals of Upper Georgia Centered in Gilmer County (Nashville: The Parthenon Press, 1965) which misidentifies the companies and captains at Fort Hetzel and the local militia captain, assigns joint command of Cherokee removal to the three US officers who served sequentially, misstates the date removal began, and overstates the number of Cherokees sent from Fort Hetzel, the number removed from Gilmer County, and the number sent to Indian Territory. |

| 3. | Two recent studies provide useful correctives for two removal posts: Stephen Neal Dennis, A Proud Little Town: LaFayette, Georgia 1835–1885 (LaFayette, GA: Walker County Governing Authority, 2010), 191–313; John W. Latty, Carrying Off the Cherokee: History of Buffington’s Company, Georgia Mounted Militia (published by author, 2011). It is a pleasure to acknowledge the uncommon generosity of both authors and recognize Stephen Neal Dennis’s summaries and expert guidance through military records in the National Archives. |

| 4. | John Mitchell’s 1775 map, reprinted in part by John Swanton for the Bureau of American Ethnology, shows Ellijay north of Kittuwha, the Cherokee mother town in present-day North Carolina: "The Southeastern Part of the Present United States from the Mitchell Map of 1755," Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 73, Plate 6, back papers (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1954). James Mooney identifies four such towns, one in South Carolina on the Keowee River, one in North Carolina on Ellijay Creek of the Little Tennessee River, a third in Tennessee on Ellejoy Creek of Little River, and the fourth in Gilmer County, Georgia: James Mooney’s History, Myths, and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokees (Asheville, NC: Historical Images, Bright Mountain Books, 1992), 517. See also The Payne-Butrick Papers, ed. William L. Anderson, Jane L. Brown, and Anne F. Rogers, vol. 2 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010), 224. Francis Varnod, "A True and Exact Account of the Number and Names of All the Towns Belonging to the Cherrikee Nation," in Peter H. Wood, Gregory A. Waselkov, and M. Thomas Hatley, eds., Powhatan’s Mantle: Indians in the Colonial Southeast (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989), 62. |

| 5. | Varnod, 62. |

| 6. | "Journal of Colonel George Chicken’s Mission from Charleston, S.C. to the Cherokees, 1726," in Newton D. Mereness, ed., Travels in the American Colonies (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1916), 110–11, 126. |

| 7. | Christopher French, "An Account of the Towns in the Cherokee Country with Their Strengths and Distance," in Journal of Cherokee Studies 2 (Summer 1977): 297; Christopher Gadsden, "A Particular Scheme of the Transactions of Each Day…from the 7th of June…to the 4th of July When They are Supposed to Return to the Dividings," Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. |

| 8. | Bartram listed the Tennessee, Savannah, Tugalu, and Flint Rivers: Gregory A. Waselkov and Kathryn E. Holland Braund, eds., William Bartram on the Southeastern Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990), 88. See also Betty Anderson Smith, "Distribution of Eighteenth Century Cherokee Settlements," in The Cherokee Nation: A Troubled History, ed. Duane King (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1979), 46–60. |

| 9. | See J. G. M. Ramsey, The Annals of Tennessee to the End of the Eighteenth Century (1853. Reprint. Johnson City, TN: The Overmountain Press, 1999), 270–73. |

| 10. | An unpublished history of the family of Samuel Smith mentions his visit to Ellijay in Georgia in the 1780s: "Something About Some Smiths: An Account of Part of the Samuel Smith Family Dating from 1730 and Ending 1969," 9. I am grateful to Jeff Bishop for providing me with a copy of this family history. |

| 11. | Cherokee County Section 2, District 11, District Plats of Survey, Survey Records, Surveyor General, RG 3-3-24, Georgia Department Archives and History (hereafter cited as GDAH); James B. Henson advertisement, Western Herald, March 21, 1834, and Report of Mail Routes, The Western Herald, April 18, 1834; James J. Field to A. R. Hetzel, 27 March 1838, RG 92, Entry 352, Box 3, National Archives (hereafter cited as NA). |

| 12. | See William G. McLoughlin and Walter H. Conser, Jr., "The Cherokee Censuses of 1809, 1825, and 1835," in William G. McLoughlin, Walter H. Conser, Jr., and Virginia Duffy McLoughlin, The Cherokee Ghost Dance: Essays on the Southeastern Indians, 1789–1861 (Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 1984), 215–250. |

| 13. | "1835 Cherokee Census," Monograph Two (Park Hill, Ok: Trail of Tears Association Oklahoma Chapter, 2002), 41–42. |

| 14. | Charles Hicks to Alexander McCoy and Nathan Hicks, 1824, MS 2033, Penelope Johnson Allen Collection, Hoskins Special Collections Library, University of Tennessee, Knoxville. |

| 15. | See Mooney’s History, 113–14; William G. McLoughlin, Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), 191–92, and Cherokees and Missionaries, 1789–1839 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984), 213–38. |

| 16. | In the same era Cherokees adopted a constitution establishing a republican form of government and a nation-wide judicial system (1827). Having declared their sovereignty and national boundaries the Cherokee Nation challenged Georgia’s actions in two Supreme Court cases (1830, 1832). The court declined to rule in the first case. Although the Cherokees prevailed in the second (Worcester v. Ga.), the federal government’s executive branch refused to enforce the decision. |

| 17. | William Hardin to Wilson Lumpkin, 29 March 1832, in Mrs. J. E. Hayes, comp., Cherokee Letters, Talks, and Treaties, GDAH, 340. |

| 18. | See Sarah H. Hill, "'To Overawe the Indians and Give Comfort to the Whites:' Preparations for the Removal of the Cherokee Nation from Georgia," Georgia Historical Quarterly 95, no. 4 (Winter 2011): 465–97. |

| 19. | "Atrocious Injustice," Cherokee Phoenix, May 18, 1833. See also Stephen Griffeth to George R. Gilmer, 25 February 1838, Georgia’s Virtual Vault, General Name File, Gilmer, George R., GDAH. For a story from the Georgians see "Indian Difficulty," a Western Herald, November 16, 1833 report that Cherokees killed workmen and burned a mill near Ellijay. |

| 20. | John Shaw to Adj. General, 19 June 1836, RG 94, M567, Roll 131, Entry 12, S-241, NA. In accord with state authorization Derrick raised the company on Jan. 7, 1836: Georgia Military Affairs, Mrs. J. E. Hays, copier and indexer, vol. 8, 1836–1837 (Atlanta: WPA Project 5993, 1940), 47. |

| 21. | John E. Wool to William E. Derrick, 11 November 1836, RG 94, M567, Roll 154, Entry 12, W-138, NA; Wool to Derrick, 14 November 1836, and Thomas C. Lyon to Derrick, 21 November 1836, John E. Wool Papers, Box 52, File 19, Letter Book, July, 1836-April, 1837, New York State Library, NY (hereafter cited as Wool Letter Book, NYSL). |

| 22. | I am grateful to Stephen Neal Dennis for providing me with information about the composition of Derrick’s company. The composition likely varied from attrition due to illness or dismissal as well as the limited service periods of three or twelve months. |

| 23. | A. R. Hetzel to T. Crim, 5 January 1837, RG 92, Entry 350, Box 2, Vol. 1, Hetzel Letter Book, NA, 148; John E. Wool Order 23, 23 January 1837, RG 94, Entry 44, Vol. 13, 569, NA. |

| 24. | John E. Wool to William E. Derrick, 25 March 1837, Wool Letter Book, NYSL, 340; Wool to Derrick, 21 May 1837, RG 94, Entry 12, M567, Roll 154, W-214, NA. |

| 25. | Wool Order 11, 22 March 1837, RG 92, Entry 357, Box 6, NA; John E. Wool to William E. Derrick, 25 and 28 March 1837, Wool Letter Book, NYSL, 339–40, 346–47. P. M. Wear to William E. Derrick, 30 March 1837, Wool Letter Book, NYSL, 340; H. B. Shaw to Joseph Byrd, 10 April 1837, RG 94, Entry 12, Roll 154, W-179, NA. Big Frog Mountain is north of Ellijay. |

| 26. | P. M. Wear to William E. Derrick, 30 March 1837, Wool Letter Book, NYSL, 340; H. B. Shaw to Joseph Byrd, 10 April 1837, RG 94, Entry 12, Roll 154, W-179, NA. Big Frog Mountain is north of Ellijay. |