Overview

Andrew Denson reviews Steve Inskeep's Jacksonland: President Andrew Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and a Great American Land Grab (New York: Penguin Press, 2015).

Review

In May 2015, journalist Steve Inskeep wrote an op-ed for the New York Times arguing that nineteenth-century Cherokee leader John Ross should be featured on the opposite side of the twenty-dollar bill from Andrew Jackson. Jackson contributed greatly to the expansion and development of the United States, Inskeep noted, but this "nation-building" occurred with devastating costs for Native peoples, whom he fought as a military commander and displaced using the Indian Removal policy during his presidency. As Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, Ross counted among Jackson's vocal adversaries. Placing Ross on the nation's currency, Inskeep implied, would represent a measure of symbolic justice. Inskeep suggested putting Ross on one side of the bill, with Jackson on the other.

In Jacksonland, Inskeep offers the book-length equivalent of his op-ed. He narrates Cherokee Removal through the lives and careers of Jackson and Ross, presenting parallel biographies. He charts Jackson's rise from frontier lawyer and land-speculator to military commander and national politician and details Ross's life as a Cherokee merchant, slave-owning planter, and tribal leader. Inskeep describes the state of Georgia's campaign to expel the Cherokee people amid the national debate over removal policy, one of the most significant and contentious issues of Jackson's first term as President. As Principal Chief, Ross led the Cherokee Nation's resistance to removal, a campaign fought on multiple fronts: on Native lands, in political arenas, in the local and national press, and in federal court. When these efforts failed, Ross led his people west and began the work of rebuilding the Cherokee Nation in Indian Territory. Ross and Jackson's stories are well-known, and Jacksonland offers little new or surprising material. Writers popular and academic have long served up Cherokee Removal as a measure of an emergent nation's moral capacity.1Significant works include William G. McLoughlin, Cherokees and Missionaries, 1789–1839 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984); William G. McLoughlin, Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986); Thurman Wilkins, Cherokee Tragedy: The Ridge Family and the Decimation of a People, rev. ed. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1986); Cherokee Removal: Before and After, ed. William L. Anderson (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1991); Jill Norgren, The Cherokee Cases: The Confrontation of Law and Politics (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1996); Theda Perdue, Cherokee Women: Gender and Culture Change, 1700–1835 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998); Tim Alan Garrison, The Legal Ideology of Removal: The Southern Judiciary and the Sovereignty of Native American Nations (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2002); Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green, The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears (New York: Viking, 2007). Inskeep tells much of this familiar story effectively, reminding readers that the creation of the South and its flourishing slave society relied upon the violent expulsion of indigenous peoples.

Right, Major General Andrew Jackson, Philadelphia, ca. 1820. Portrait by Thomas Sully, engraving by James B. Longacre. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, loc.gov/item/96521560/.

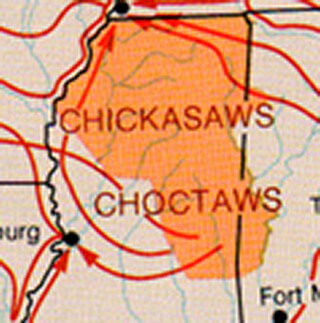

Inskeep presents Jackson as a crucial architect of the antebellum South. He suggests that the key moment of Jackson's early career was not the Battle of New Orleans, where he defeated the British, but his earlier command of militia in the Creek War of 1813–1814. In this brutal conflict, Jackson suppressed Creek nativists known as Red Sticks, later forcing the cession of more than twenty million acres of land in what became Alabama and southern Georgia. This episode epitomized Jackson's ruthlessness and his compulsion to expand American territory. He made this portion of the southeast into "Jacksonland," beginning his lifelong project of turning Indian homelands into US possessions.

John Ross also participated in the Creek War, joining a Cherokee force that fought the Red Sticks as allies of the United States. For Inskeep, Ross's service represents the effort of some Cherokees during this period to accommodate an expanding American republic. This work involved cultural, economic, and political adaptations, rewarding Cherokees with the public image of a "civilized tribe." In the years after the Creek War, as Jackson pursued public office, Ross emerged as a significant Cherokee tribal leader. He participated in the early nineteenth-century creation of a Cherokee national government, a process that culminated in the drafting of the 1827 Cherokee Constitution. Ross then became chief executive of that government in 1828, the same year Jackson won the White House.

With Ross and Jackson both occupying offices of leadership, Inskeep narrates the struggle over Indian Removal. He details the state of Georgia's campaign of violence and harassment against Cherokees and the national debate over the Indian Removal Act. He notes the work of middle-class white women who sought to prevent its passage. He describes Cherokee efforts to defend themselves in the US Supreme Court and Jackson's refusal to enforce the Court's ruling. At times, Inskeep's reliance on biography becomes a liability. He implies that Jackson was the main author of the removal policy, rather than one powerful advocate among many. Inskeep further suggests that removal was novel in the late 1820s, rather than an approach to Indian relations that dated to the beginning of the century. With his focus largely on the nation's capital and Jackson's presidency, Inskeep makes removal too much the president's story, erasing complexities of antebellum political life.

A more significant problem lies in Inskeep's inattention to Cherokee history and culture. For a book that names a Cherokee leader in its subtitle, Jacksonland offers remarkably little information on how Cherokee people lived, thought, or conducted their political affairs. Readers learn what land meant to white Americans in the South, but Inskeep pays scant attention to Cherokees' relationship with their homeland. He notes the creation of a Cherokee national government, but writes little about the political traditions among Cherokees that made the emergence of that government such a remarkable and contentious development. The Cherokees become a racial minority within the United States, rather than members of an indigenous polity seeking to protect itself against an invading empire.

In Jacksonland's strongest sections, Inskeep surveys the many ways Jackson merged service to the United States with his personal financial interests. As military leader and federal treaty commissioner, Jackson opened millions of acres of Native American land to non-Indian settlement. Making profitable use of inside information, Jackson, his friends, and his political allies secured some of the best properties, growing wealthy on the gold-rush economy of the cotton boom. In the antebellum era, national defense and wellbeing always involved real estate and market agriculture. For Americans like Jackson, the common good required the erasure of Indian peoples as landowners and their replacement with white settlers (and, in the South, their black slaves). The United States could secure freedom and economic opportunity for its white citizens only by expelling indigenous communities. That men like Jackson profited from coerced treaties illuminates the connections among capitalism, nineteenth-century conceptions of American nationhood, and the forceful dispossession of Native peoples.

The best aspect of Inskeep's book may be its title—or rather the idea of America and the South implied by the term "Jacksonland." The United States is Andrew Jackson's country, a nation born in violent conquest. The early republic did not expand naturally into empty western lands. People like Jackson created the United States from the territory of other nations. The essence of American national identity lies not only in the high-minded principles of the Revolution, but in the volatile mixture of aggressive capitalism, white supremacy, and violence epitomized by Old Hickory. Who better to adorn the twenty-dollar bill?

About the Author

Andrew Denson is graduate program coordinator and associate professor of history at Western Carolina University. He teaches courses on Native American and United States history and participates in WCU's Cherokee Studies program. Denson is author of Demanding the Cherokee Nation: Indian Autonomy and American Culture (University of Nebraska Press, 2004).

Recommended Resources

Text

McLoughlin, William G. Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Norgren, Jill. The Cherokee Cases: Two Landmark Federal Decisions in the Fight for Sovereignty. Reprint. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2003.

Perdue, Theda and Michael D. Green. The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears. New York: Viking, 2007.

Wilentz, Sean. The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln. New York: W. W. Norton, 2005.

Web

Andrew Jackson Foundation. Andrew Jackson's Hermitage: Home of the People's President. http://thehermitage.com.

Hicks, Brian. "The Cherokees vs. Andrew Jackson." Smithsonian Magazine, March 2011. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-cherokees-vs-andrew-jackson-277394/.

Jaffee, David. "Visual Evidence in Jacksonian America." Picturing U.S. History. http://picturinghistory.gc.cuny.edu/visual-evidence-in-jacksonian-america/.

National Institutes of Health and Human Services. US National Library of Medicine. "Native Voices: Native Peoples' Concepts of Health and Illness." https://www.nlm.nih.gov/nativevoices/.

National Museum of American History. Smithsonian Institute. "Eastern Indian Wars." The Price of Freedom: Americans at War. http://amhistory.si.edu/militaryhistory/exhibition/flash.html.

Ohlheiser, Abby. "Why is Andrew Jackson on the $20 bill? The answer may be lost to history." Washington Post, June 17, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2015/03/06/why-is-andrew-jackson-on-the-20-bill-the-answer-may-be-lost-to-history/.

Public Broadcasting Service. American Experience Series. We Shall Remain. Documentary, 2009. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/weshallremain/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Significant works include William G. McLoughlin, Cherokees and Missionaries, 1789–1839 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984); William G. McLoughlin, Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986); Thurman Wilkins, Cherokee Tragedy: The Ridge Family and the Decimation of a People, rev. ed. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1986); Cherokee Removal: Before and After, ed. William L. Anderson (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1991); Jill Norgren, The Cherokee Cases: The Confrontation of Law and Politics (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1996); Theda Perdue, Cherokee Women: Gender and Culture Change, 1700–1835 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998); Tim Alan Garrison, The Legal Ideology of Removal: The Southern Judiciary and the Sovereignty of Native American Nations (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2002); Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green, The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears (New York: Viking, 2007). |

|---|