Overview

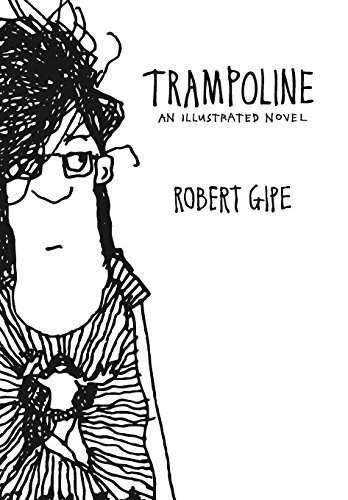

Carter Sickels reviews Robert Gipe's illustrated novel Trampoline (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2015).

Review

Since the late nineteenth century, Appalachia has been exploited, sensationalized, or deeply romanticized across literature, art, and popular culture. The "local color" authors after the Civil War depicted stereotypes of the region that still endure; think of the toothless, bearded hillbilly with a jug of moonshine, or simple folks carving wood or making quilts. A hundred years later, James Dickey's Deliverance didn't help things— portraying Appalachian people as menacing, stupid, and inbred. The damaging stereotypes of Appalachia persist, as Emily Satterwhite explains in Dear Appalachia: Readers, Identity, and Popular Fiction Since 1878: "Appalachia in the national geographic imaginary . . . has largely remained an essentialist vision of the region—white, rural, poor or working-class mountain people with highly specific cultural traditions that range from quilts and handmade crafts to moonshining and snake handling" (3).

But perhaps as we move into the twenty-first century, the many complicated, rich, and diverse depictions of Appalachia that shatter these stereotypes will take a more prominent place in the national imagination. In particular, Appalachian literature is vast, and encompasses a wide range of voices and subjects. Some of Appalachian literature's most acclaimed and best-known authors include James Still, Harriette Simpson Arnow, Wendell Berry, Jim Wayne Miller, Denise Giardina, and Lee Smith. Younger Appalachian authors include Silas House, Ann Pancake, Amy Greene, and David Joy, among many others. Appalachian authors of color including Nikky Finney, Crystal Wilkinson, Jacinda Townsend, and Frank X Walker dispel pervasive beliefs that Appalachia is white and homogenous. These many diverse voices of Appalachia challenge the idea of a singular Appalachian experience or identity, and Robert Gipe's Trampoline now joins the rich tapestry of Appalachian literature.

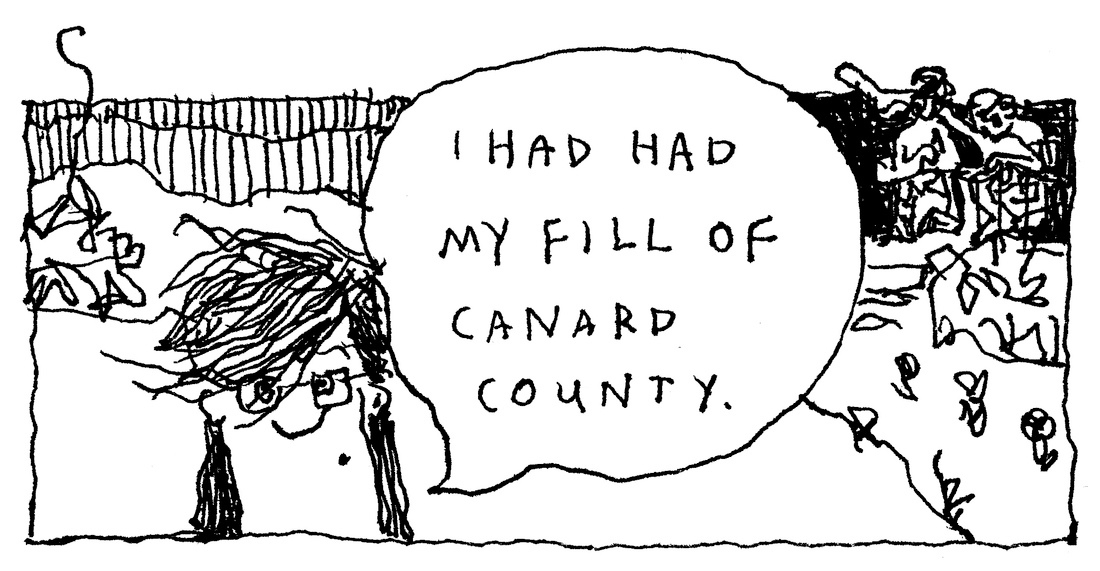

"I had had my fill of Canard County," fifteen-year-old Dawn Jewell proclaims in the opening cartoon panel of Trampoline (1). Canard County is a fictional county in Eastern Kentucky. It's rural, poor, and white. Coal mining, unemployment, drug addiction, and religious fervor dominate the landscape and the culture. It is, in other words, straight-up Appalachia. But as Trampoline embraces its Appalachian-ness, it also questions commonly held notions of what it means to be Appalachian. Its combination of prose narrative and quirky illustrations delivers a unique storytelling form, and the insightful, hilarious, and honest protagonist Dawn Jewell makes Trampoline unforgettable.

Appalachian literature commonly explores themes of place, community, and identity. In Trampoline, Canard County is both a source of chaos and comfort for Dawn, and it's deeply tied to her family—it's impossible to separate the two. Most of Dawn's family lives in the region, but don't offer much stability—a ragged bunch of cousins and "outlaw" uncles and family friends with wonderful names, by the way: Crater, Decent, Pickle, Cinderella, Big Jan. Dawn rarely sees her flighty mother who started "grieving out of a Heaven Hill bottle" after Dawn's father was killed in a mining accident, and she fights constantly with her brother (35). Her aunt June now lives in Kingston, Tennessee, in a "hippie" community; after she disentangled herself from the family, she had to "build herself a fortress of solitude" (220). And, yet, June admits that she misses the family "racket." Most of the time Dawn stays with her grandmother, who is leading a grass-roots effort to petition the governor to stop the stripmining of Blue Bear Mountain, which rises behind the family's home place. Her grandmother is the most stable, and heroic, member of the family.

Trampoline explores the tenacity of ties—in the ways that they offer love and protection, and the ways in which they suffocate. Dawn reaches a point of exhaustion and clarity when she crashes her uncle's car and everything spills out from the glove box; she envisions herself as "the cowboy in the movie when he gets trapped under his horse, except instead of a horse I was trapped under a pile of my family's shit" (42).

Trampoline is a story about Appalachia, and a coming-of-age tale about a teenager trying to find her voice. Dawn wants to figure out who she is and where she belongs. It's refreshing to read an Appalachian novel in which the protagonist is a smart and sharp-tongued young woman who doesn't mince words. Discussing other kids at school, Dawn attests, "The retardation around here staggers the mind" (129), and she describes a classmate's eyes as "dull as social studies, and she had no idea men had been to the moon" (166). Dawn is as tough as Ree Dolly in Daniel Woodrell's Winter's Bone, but not as grim—her wry humor brings a note of levity to the narrative, reminiscent of Gurney Norman's Kinfolks. Dawn's world is difficult, but not hopeless or humorless.

The characters in Trampoline may be Appalachian, but that doesn't mean they fit neatly into any particular mold. Dawn, for example, isn't interested in making quilts or playing a fiddle. She prefers punk to bluegrass, and wears black nail polish. When she hears a Black Flag song for the first time, something awakens in her: "The guitars sounded like power tools being run too hard. I'd never heard such before" (3). She drinks liquor, gets in fights, and cuts school. "I was a freak, soft and four-eyed," Dawn describes herself (70). Trampoline celebrates weirdness and difference. Dawn falls for dorky Willett Bilson—a chubby guy with a drooling problem, whom she first hears over the radio waves. Bilson deejays at his family's community radio station out of Tennessee and plays punk records. He's smart and kind, and like Dawn, a misfit: "Willet stood in front of me, breathing through his mouth, and I wanted to squeeze his big soft head. The feeling was new and strange" (258).

The hand-drawn illustrations, over two hundred of them, emphasize Dawn's strong, memorable voice, and give us a picture of what she looks like, or at least how she views herself—her big messy hair that later turns into a mowhawk, her glasses, and exaggerated chin. Trampoline isn't a traditional graphic novel; the drawings slip in and out of the narrative prose. The comic panels typically depict Dawn speaking; they add intimacy and emphasis to her voice, and give readers another way to hear her. As the illustrations let readers get a look at Dawn, she looks back at the reader, redirecting the gaze.

Just as coal mining has indelibly impacted the Appalachian landscape, it haunts the pages of Appalachian literature. In Trampoline, Dawn's grandmother leads the fight to stop the stripmining of Blue Bear Mountain. The novel takes place in 1998 (we don't find this out until late in the narrative), when mountaintop removal coal mining, an extreme version of the already devastating stripmining, was growing more prevalent. The novel foreshadows the intense fights between coal supporters and environmentalists that occurred as more massive MTR operations amped up across Appalachia. In a mountaintop removal operation, the coal company uses millions of tons of explosives to blast the mountain, removing up to six hundred feet off the mountain in order to get to the coal seams. The "overburden," which includes the mountains and toxic mining waste, is then dumped into streams and valleys. The valley fills "have buried more than two thousand miles of headwater streams and polluted many more," according to the environmental organization Appalachian Voices. In addition, "Mountaintop removal mining has destroyed more than five hundred mountains, encompassing more than one million acres of central and southern Appalachia" (Appalachian Voices). The mining has not only destroyed mountains and diverse forests, but ruined drinking water, caused flash floods, forced people to leave their ancestral homes, and cut jobs (since mining companies have mechanized, they need fewer miners). Despite the loss of jobs and the destruction of the land, loyalty to the coal companies still runs high; the industry's strong hold over minds and hearts persists.

As the granddaughter of a "treehugger," Dawn doesn't win many friends at a high school where most of the students have family working for the coal company and Friends of Coal stickers decorate the principal's office. When she stands up for her grandmother at a community meeting, Dawn gets pulled into the fight and—somewhat reluctantly—emerges as an environmental spokesperson.

Gipe doesn't sidestep the complexity of coal mining in the region, or the volatile emotions. For example, at a party in Kingston, populated by "hippie enviro fighters," Dawn recognizes that the Christmas lights depend on electricity and coal (222). At this same party, Dawn also learns about the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, and about the history of her people—Appalachians who have been fighting the coal companies since the '60s, including the famous Widow Combs who sat down in front of bulldozer to stop strip-mining, and Uncle Dan Gibson, who held off the coal company with a shotgun. The region's lack of options and the citizens' lack of power make employment complicated, as Dawn realizes about her uncle and cousin, both coal miners: "They loved it here, and they had to tear it up to stay" (226).

As coal companies destroy the mountains and family homes, pill addiction ravishes communities across Appalachia. In Trampoline, drugs quell sadness and boredom; the novel foreshadows how the drugs' hold over a place and people will intensify. During the late '90s and early 2000s, Oxycoden started to enter Eastern Kentucky, and Gipe captures its looming presence in an illustration of the word in all capital letters; Dawn says, "It was the first time I ever heard the word." (302). Prescription pill addiction, and oxy in particular, hit Eastern Kentucky hard. Recently, many users have been turning to heroin, the cheaper alternative. In 2013, there were estimates of over a thousand deaths from opioid overdoses in Kentucky.

Dawn glimpses this impending devastation, and already knows how addiction wrecks families and destroys lives. Her mother steals money from her and from Dawn's grandmother, and tries to exploit Dawn's injury to obtain a prescription. Gipe doesn't romanticize or vilify his drug-addicted characters, but just presents them as they are: "There were new gaps between her teeth" (38). Gipe depicts the complex reality of loving an addict—the endless cycle of anger and heartache, such as in one poignant scene when Dawn's stoned mother climbs up a tree, and the family gathers around trying to coax her back down safely: "We were scared for her, but her buzz brought a tiredness, an about-wore-out-ness to our worry" (85). The moment exhibits fear and anxiety, but also tenderness as Dawn looks up at her mother: "She waved at me. Light flooded her from behind. In a way, I did not want her to come down. I was glad to see her so high up. She had not escaped, but she was closer" (86).

Gipe doesn't paint a romanticized picture of Appalachia, but he also doesn't exploit the region. He writes from inside. His ear for dialogue is outstanding. He writes the way people talk. When characters say, "Daggone… You're worser than me" (2), and "they's beer and pop in the cooler" (94), the dialogue doesn't make the characters sound uneducated. Instead, the vernacular dialect sounds natural and authentic, and makes you feel like you're in the room with the characters. Dawn says, "I wadn't done" (16), "I seen broken glass" (31), and "They all knew then Pickle was going to go ahead and get redneck" (99). Her dialect never undermines her sharp, often poetic observations, but reinforces their authenticity.

Gipe's prose delights with its directness and surprising, fresh images. For example, at the town meeting, where people have gathered to speak in favor or against coal mining, Gipe describes the government people in their suits: "The state people sat like prizes at a carnival game, eyes wide and blank, stuffed pink monkeys, green hippopotamuses piled too close together. Every once in a while they would take a note, but not that often" (12). Page after page demonstrates Gipe's imaginative prose, such as this wonderful line: "The skinned trees stood gray and clear like old people talking, no word wasted" (175). Or, when Hubert comes to pick up Dawn at the police station, "He looked like somebody in some low-ceiling white-light don't give-a-shit-how-bright-things-are church. Had he raised up a rattlesnake above his head and started speaking in tongues I wouldn't have been surprised" (195). Gipe takes overused Appalachian motifs, and defamiliarizes them in ways that are fresh and often hilarious.

Gipe is funny but not cynical, and compassionate without falling into sentimentality. Even when Dawn longs for a simpler time, the nostalgic yearning isn't cloying or sentimental, as in this moment when she thinks about her papaw Houston: "I could see him in my mind, surrounded by his music, fire going in the stove, not like pioneer days, not that old feeling, but like something you couldn't find no more in the world today" (58). Gipe doesn't sidestep the dire effects of poverty and addiction in a place where there just aren't many options. The world captured in these pages is often painful and often dark, but also lit by wry humor and tenderness. Gipe is a generous writer, and he gives his characters the gift of change and openness. There is a grace these characters possess, like fat Denny climbing so fast up the tree, like a bear, to save Dawn's mother. Trampoline portrays Appalachia at its most complex, heartbreaking, and beautiful.

About the Author

Carter Sickels is author of the novel The Evening Hour (New York: Bloomsbury, 2012), a finalist for the 2013 Oregon Book Award and the Lambda Literary Debut Fiction Award. He is recipient of the 2013 Lambda Literary Emerging Writer Award, a project grant from Oregon's RACC, and an NEA Fellowship to the Hambidge Center for the Arts. He's been awarded fellowships or scholarships to Bread Loaf Writers' Conference, the Sewanee Writers' Conference, and the MacDowell Colony. He is editor of the anthology Untangling the Knot: Queer Voices on Marriage, Relationships, and Identity. Carter is assistant professor of Creative Writing at Eastern Kentucky University and teaches in the Bluegrass Writers Studio low residency MFA program.

Cover Image Attribution:

"I was never going to get out from under this place," © Robert Gipe, 2015. Originally published in Trampoline (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2015), 58. This material is used by permission of Ohio University Press, www.ohioswallow.com.Recommended Resources

Text

Biillings, Dwight B., Gurney Norman, and Katherine Ledford, eds. Back Talk from Appalachia: Confronting Stereotypes. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1999.

House, Silas and Jason Howard, eds. Something's Rising: Appalachians Fighting Mountaintop Removal. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2009.

McNeil, Bryan T. Combating Mountaintop Removal: New Directions in the Fight Against Big Coal. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2011.

Norman, Gurney. Kinfolks:The Wilgus Stories. Frankfort, KY: Gnomon Press, 1977.

Pancake, Ann. Strange as This Weather Has Been. Berkeley, CA: Shoemaker & Hoard, 2007.

Rash, Ron. Above the Waterfall. New York: Harper Collins, 2015.

Satterwhite, Emily. Dear Appalachia: Readers, Identity, and Popular Fiction Since 1878. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2011.

Sickels, Carter. The Evening Hour. New York: Bloomsbury, 2012.

Woodrell, Daniel. Winter's Bone. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2006.

Web

Applachian Symposium 2015. Berea College Loyal Jones Appalachian Center. https://www.berea.edu/appalachian-center/as15/.

Appalachian Voices. http://appvoices.org/.

Baird, Sarah. "Stereotypes Of Appalachia Obscure A Diverse Picture." NPR Code Switch. April 6, 2014. http://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2014/04/03/298892382/stereotypes-of-appalachia-obscure-a-diverse-picture.

Finn, Scott. "The Front Porch: Who's to Blame for Appalachia's Drug Addiction?" West Virginia Public Broadcasting. May 29, 2015. http://wvpublic.org/post/front-porch-whos-blame-appalachias-drug-addiction.

Inside Appalachia. West Virginia Public Broadcasting. http://www.npr.org/podcasts/381443598/inside-appalachia.

Looking at Appalachia. http://lookingatappalachia.org/.

Williamson, Kevin D. "Appalachia: The big white ghetto." The Week. January 24, 2015. http://theweek.com/articles/452321/appalachia-big-white-ghetto.

Film

Winter's Bone. DVD. Directed by Debra Granik. Lionsgate, 2010.