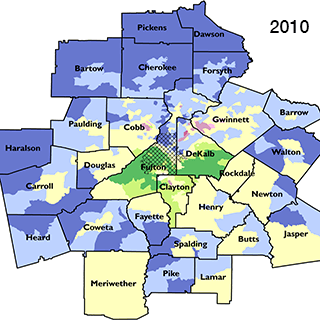

Overview

This publication pairs a video presentation featuring Jim Grimsley speaking about How I Shed My Skin: Unlearning the Lessons of a Racist Childhood (Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books) with John Howard's review of the book. In a series of video clips, Jim Grimsley talks about writing his memoir, reads an excerpt, and answers questions during a February 17, 2015, event hosted at Emory University. John Howard responds to Grimsley's memoir of growing up in eastern North Carolina.

Presentation and Review

Civil rights narratives often empower and embolden, promoting faith in possibilities, hope for rectifying inequities. More sober assessments show that, though we've come a long way—thanks to mighty black struggle and interracial coalition—there's still far to go. Honoring local achievements while warning of persistent injustice, Jim Grimsley's bold memoir of a racist white upbringing forecloses sentimentality with resolute honesty, charting slow, hard-earned change and the author's ongoing efforts to unlearn the lessons of childhood. Integration's chief foe, he suggests, is the hardwired racism of "good people" (72)—a phrase you'll never hear in the same way again.

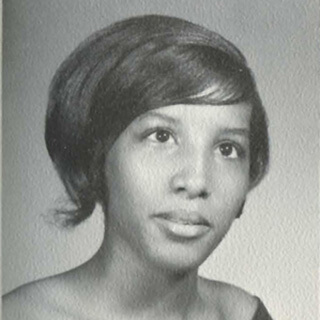

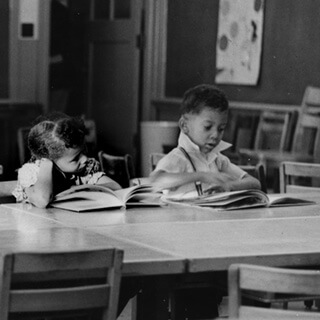

In 1966, Jimmy Grimsley, thirty other white students, and three new African American classmates Rhonda, Ursula, and Violet forged a "tepid and partial desegregation" (40) of their sixth grade classroom in rural Jones County, North Carolina, where public schools officially desegregated under a begrudging gradualist "Freedom of Choice" plan. Describing himself as "a good little racist" (18), Jimmy was the first to hurl an epithet at chubby Violet. When she spoke back with poise and pride, giving as good as she got, Grimsley began the most important educational journey of his life: unlearning entrenched habits of race and gender. "Skin color and difference" (ix), as he labels them, were linked to the body, its desires, sexual norms, and deviances. Grappling with his own sense of difference, Jimmy was more willing than most to question dominant structures of white authority and racial inequality.

Quizzical, effeminate, a hemophiliac forbidden boys' rough play, Jimmy remembers thriving after his working-class family moved into the town of Pollocksville where he could walk to the library and read widely. He absorbed novels and teen magazines, and caught glimpses of new classmates Rhonda and Ursula's Ebony and Jet. He credits the media, including television, with introducing him to dominant racist, as well as emergent anti-racist, representations: Bill Cosby's role in I Spy and Nichelle Nichols's in Star Trek. Remembering his sixth-grade self, Grimsley appears perplexed, since "adults rarely explained" (8) the unprecedented circumstances of judicial desegregation, speaking only in "coded, guarded" (10) language.

|

| Photograph of a young Jim Grimsley, age 11, Jones County, North Carolina, 1966. Courtesy of Algonquin Books. |

The transformations from sixth to seventh grade, from lackadaisical Mr. Vaughn's class to the precise Mrs. Ferguson, from foe to friend of black classmates, helped expose southern white culture's feigned warmth, courtesy, and piety. While hindsight affords Grimsley insight into the significance of his middle school years, at the time—about most matters of importance—Jimmy "had no idea" (6) and had never imagined the stark realities that delineated his racial experience.

Just when I, as a reader, suspect Grimsley is overstating his youthful naiveté—characterizations of "the Southerner" clanging, only occasionally qualified by "white"—he unearths racism's roots with brute force. In the chapter "The Learning," Grimsley shows how bias, seemingly timeless and naturalized in nursery rhymes, in fact, emanates from adults' repetitive aggressive assertions of supremacy. If racist verses structure childhood games—sung on playgrounds, chanted outside churches—a vast repertoire of nigger jokes reveals how entrenched and persistent white anxieties remain, situating prejudice in the here and now. This repertoire documents a cruel and pernicious counterpart to the long, affirmative tradition of African American trickster tales. With grace, Grimsley retells not a single joke, nary a punch line. He nonetheless explains their gruesome logic, pinpointing their myriad implications. In short, his father's and friends' jokes are variations on the theme of inferiority, castigating blacks as lazy, ugly, smelly, dirty, sloppy, unruly, faulty, sorry. Seemingly told in jest, they united whites around racist ideology. "When we laughed at the joke[s], we accepted the premise" (79).

Though Grimsley remembers hearing these jokes in many places—"at a country store or a service station, places where men talked to other men" (79)—he recalls local churches as teaching the worst lessons. There, racist discourse flowed between adults, between Sunday School and worship services, as well as mid-week meetings, at both the Baptist and Methodist churches he attended. Grimsley's chapter "Divinely White" spotlights the broad influence of Jim Crow Christianity's supremacist symbolism. He repeats no clichés about the most segregated hour of the week—that was a given. Instead, he writes that "the stratification . . . went beyond this" (93), beyond the small-town hierarchies ranging from Pentecostal to Episcopalian. "The Christian Bible" he adds, "depicted God's son as a white-wooled lamb, God's adversary as a prince of . . . darkness, salvation as a cleansing that leads to shining whiteness. God, Christ, and all the angels wore white. Death and sin were robed in black" (94). Regardless of what was preached from the pulpit—about Ham, about biblical justifications of slavery—Grimsley remembers the so-called good book making the racist points, over and over, with crude color-coded metaphors.

|

|

| Location of Jones County in North Carolina (top) and location of Pollocksville in Jones County, North Carolina (bottom). Maps by Southern Spaces, 2015. |

Faithfully reporting his county's dismal history of Native expulsion and African slavery, sexual assaults on black women and lynchings of black men, Grimsley implicitly denounces violence, hatred, and ignorance. More so, How I Shed My Skin carefully and candidly calibrates levels of fear and knowing among his fellow white southerners. As he demonstrates, whites with disabilities in Jones County, including his father, rejected chin-up resilience and vented their rage at African Americans. At the other end of a narrow spectrum, Grimsley has no truck with milquetoast liberalism. As he testifies, "nearly every white person I have spoken to about this time [said] 'We were not allowed to use the word "nigger" in my family.' One should remember," Grimsley instructs, "that most Southern mothers also proscribed such words as shit, fuck, and cunt, often to no effect whatsoever" (87–88). The power of How I Shed My Skin lies in its ability to illuminate the many inequalities ingrained beneath a veneer of pervasive politeness.

In addition to racism, Grimsley connects the dots of sexism, homophobia, and other categories of difference, notably class. As in many southern jurisdictions unable to afford one good school system, much less two, when Jones County consolidated its black and white facilities, white parents birthed a segregation academy. A new sort of dual system emerged. Grimsley, his siblings, and other poor whites remained in the public schools. There, his aesthete's sensibilities rarely connoted queerness, and he was seldom bullied. In the majority-black high school, tracked into the majority-white college-prep curriculum, Grimsley observes integration in some spaces: the football field, the stands, post-game dances, and the smoking patio. He notices and worries about classmates involved in discreet biracial romances. While he expects violent reprisals for color-line transgressions, none materialize. His white friend Mercy, who dated black student body president Andy, simply abandons her drunken father's home and moves in with other relatives. Determined to get out, all three students survive high school and end up at Chapel Hill. After graduating from the University of North Carolina, Grimsley migrates to the queer mecca of New Orleans.

By memoir's end, Violet (one of the three students who integrated Grimsley's middle school, the one who spoke back to him with such confidence) has conspicuously dropped out of the narrative, even as Grimsley documents a tentative multiracial circle of friends. At Jones Senior High, black students stage walkouts after a white teacher spouts racist slurs and a black teacher's job is threatened. But against elder white prophesies, desegregation doesn't incite an apocalypse. Students adjust, and the conflicts between insensitive white teacher-administrators and their black charges are managed, although not resolved.

In How I Shed My Skin's conclusion, Grimsley is one of only two white graduates to attend his fortieth high school class reunion. There, a black preacher first tells a joke at his expense then makes an anti-Semitic comment—southern religiosity (whether black or white) again unmasked. Still, the author sounds a hopeful note, crediting Violet with opening his mind in middle school.

I find most compelling Grimsley's recollections of song and dance. Dances were a rare site of integration in motion, on the ground, at the gym, after ballgames: a democracy on the dance floor. Though his "church taught that dancing was of the devil," he enjoyed "moving to music" (193). Grimsley "never danced with a boy in high school, or dated" one (198), "but when I was dancing I understood that I was one of many, not so different, not apart from the rest" (199). Only in these utopian moments does this highly individualistic autobiography gesture toward Mab Segrest's powerful collectivist Memoir of a Race Traitor from 1999.

|

In contrast to the dance floor, the gospel chorus remained color-coded. Inherited from the all-black high school, the chorus had no white members after consolidation. In a shrewd, subtle critique of Hollywood happy endings that play to audience expectations, Grimsley notes that, as a novelist or screenwriter, he might have invented a scene in which he sings alongside Violet, "proving that the separation between the races could one day be conquered" (225), systemic racism overcome by one-to-one biracial friendships. Instead, Grimsley as memoirist is frank as ever, realistic and sorrowful, acknowledging the slow pace of change and the maudlin appeal of instant reconciliation. His meditation on genre morphs into a stunning dialectic on the individual and collective, the loner-outsider desiring connection: "I would like to have lived in the world where I could have sung in that chorus, where what mattered would have been only the way my voice blended with the others, and the sound we made. I think I could have added to the music" (227).

Refusing easy redemption songs, Jim Grimsley yearns for communion. While his sexuality sets him apart—venturing to New Orleans and beyond, rarely to return—his yearning evidences a desire to be a part, to take part, his hopes steadfast in collective, common humanity. With piercing, instructive honesty, How I Shed My Skin revisits a painful time and place—different, yet not so different from the here and now—to show how racism's unexamined habits take deep and early hold.

About the Authors

John Howard is professor of American Studies at King’s College London. He is the author of Concentration Camps on the Home Front: Japanese Americans in the House of Jim Crow (2008) and Men Like That: A Southern Queer History (1999), both from the University of Chicago Press.

Jim Grimsley is professor of practice in English and Creative Writing at Emory University. He is the author of four previous novels, among them Winter Birds, which won the 1995 Sue Kaufman Prize for First Fiction from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and received a special citation from the Ernest Hemingway Foundation; Dream Boy, winner of the American Library Association GLBT Award for Literature (the Stonewall Prize) My Drowning, a Lila-Wallace-Reader’s Digest Writer’s Award winner; and Comfort and Joy.

Recommended Resources

Text

Banes, Ruth A. "Autobiography." In Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, edited by Charles Reagan Wilson and William Ferris, 19–22. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989. http://docsouth.unc.edu/southlit/autobio.html.

Boles, John B, ed. Shapers of Southern History: Autobiographical Reflections. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004.

Crews, Harry E. A Childhood: The Biography of a Place. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995.

Folkenflik, Robert, ed. The Culture of Autobiography: Constructions of Self-Representation. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 1993.

Inscoe, John C. Writing the South through the Self: Explorations in Southern Autobiography. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011.

Parcel, Toby L. and Andrew J. Taylor. The End of Consensus Diversity, Neighborhoods, and the Politics of Public School Assignments. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Parramore, Thomas C. Express Lanes and Country Roads: The Way We Lived in North Carolina, 1920–1970. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983.

Tullos, Allen. Alabama Getaway: The Political Imaginary and the Heart of Dixie. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011.

Wallach, Jennifer Jensen. Closer to the Truth Than Any Fact: Memoir, Memory, and Jim Crow. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010.

Web

Gleaves, Dayna Durbin. "A Record of School Desegregation: Conduct Your Own Oral History Project." Learn NC: K-12 Teaching and Learning from the UNC School of Education. http://www.learnnc.org/lp/pages/2709.

Brock Historical Museum of Greensboro College. "J. C. Price School, If These Walls Could Talk: An Oral History Project." Greensboro College. https://www.greensboro.edu/museum-jcprice.php.

Center for Oral Histoy and Cultural Heritage. "The Oral History Digital Collection." The University of Southern Mississippi. http://digilib.usm.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/coh.

Documenting the American South. "Oral Histories of the American South: Race and Education K-12." University Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. ttp://docsouth.unc.edu/sohp/browse/themes.html?theme_id=1&category_id=11&subcategory_id=74.