Overview

In this excerpt from Finding Purple America: The South and the Future of American Cultural Studies (University of Georgia Press, 2013), and a newly written afterword, Jon Smith tells of his efforts to create a garden—small-scale art for the long haul—in Birmingham, Alabama.

Red Mountain Garden

|

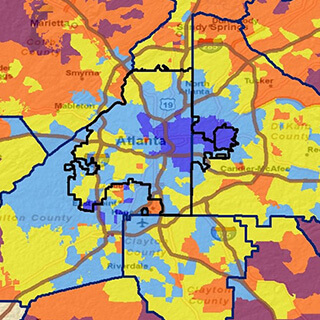

| Location of Smith's house, Birmingham, Alabama. Copyright GoogleMaps, 2013. |

My backyard garden is sited on the steep north slope of Red Mountain in Birmingham, Alabama, about sixty vertical feet down from the ridgeline and about 250 feet above downtown.1We now live in North Vancouver, British Columbia, but—since we moved during the Great Recession—we were unable to sell our Birmingham house. I have opted, therefore, to continue using the present tense and referring to the place as "our house," especially because we own no other: in North Vancouver, we are renters. In front of our home extends a suburban landscape of half–century-old houses. There is not a front porch in my entire neighborhood; whether despite or because of this, the homes—which I might generously describe as "midcentury modern"—exude a remarkable kind of 1950s optimism not ordinarily associated with the South, and from every window in the front of our house we can see, on a clear fall day, between five and fifteen miles. (Even in the post-bubble Los Angeles real estate market, this would be a multimillion-dollar view. We bought the place in 2003 for $137,000.) In the winter, when the leaves have finally fallen from the white oaks, the view includes the modern downtown skyline. Behind and above us, however, Red Mountain is too steep to build on, so there's nothing but second-growth hardwood forest and a few limestone outcrops between us and the condominiums at the top of the ridge. Through the woods just behind our lot, about twenty feet above the house, runs the old grade for the Birmingham Mineral Branch of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, which carried iron ore from the mines that still angle down into the narrow seam of ore-bearing sandstone that runs along the ridge. Today, it's a footpath that intersects, three-tenths of a mile to the east, a paved section called the Vulcan Trail, which itself runs, closed to motor vehicles, exactly a mile to the base of the Vulcan statue. In 1924, when America's leading landscape architecture firm, Olmsted Brothers, put together their proposal A System of Parks and Playgrounds for Birmingham, they recommended this area be part of a "radical expansion" of Green Springs Park (now George Ward Park) at the base of the mountain.2Olmsted Brothers, A System of Parks and Playgrounds for Birmingham: Preliminary Report upon the Park Problems, Needs, and Opportunities of the City and its Immediate Surroundings (Birmingham: Park and Recreation Board of Birmingham, 1925), 12. Reprinted by the Birmingham Historical Society, 2005. "It is worth while," they wrote, "also to provide parks of the mountain type—places where people can climb, can enjoy the wild woods, and can enjoy that sense of freedom and expansion, in contrast to the restrictions of a city, which comes with the contemplation of distant and spacious views, even though in detail these views may be largely over urban districts. Because of its height and its nearness to the city, the Red Mountain ridge is particularly fitted to this purpose."3Ibid., 20. Because the iron mines were still running at full tilt, Olmsted Brothers realistically anticipated the land would be difficult to obtain. They were right. Our neighborhood, initially Lebanese, was built shortly after the mines shut down; the city purchased the steepest section, a strip about two hundred feet wide, less because of civic foresight than because real estate developers couldn't use it. Fortuitously, that strip is today poised to become part of an extensive network of linear parks across the metropolitan region.

|

| Birmingham skyline through the white oaks. Birmingham, Alabama, March 21, 2008. Photograph by Jon Smith. |

The site is thus classically liminal, on the threshold between city and forest, automobile grid and curving mountainside. Deranged by the mountain, parallel grid lines converge here: below our house, Twenty-second Avenue intersects Twenty-first. We float on red Alabama clay between service and industry, between Birmingham's present skyline of banks and hospitals and its past mine railroad, between midcentury modern houses and neighborhood and second-growth woods that seem much older. More: Red Mountain is almost the last ridge of the great Appalachians running nearly the length of the eastern United States. Topographically if not quite culturally, Birmingham sits where the post-plantation Deep South in which I lived and worked from 1995 to 2010 meets the Appalachian South near which I grew up. When in Absalom, Absalom!, Faulkner's Thomas Sutpen falls Miltonically from the (West) Virginia mountains into the Virginia tidewater, "descending perpendicularly through temperature and climate," the landscape he plummets through on his way down—the Piedmont Virginia of Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe, all of whom would have been alive as he passed through—looks surprisingly like Birmingham's.4William Faulkner, Absalom, Absalom! In William Faulkner, Novels 1936–1940, ed. by Joseph Blotner and Noel Polk (New York: Library of America, 1990), 111.

Edward O. Wilson claims we are hardwired to want to live in places like this one. Across cultures, he argues, "people prefer to look out over their ideal terrain from a secure position framed by the semi-enclosure of a domicile. Their choice of home and environs, if made freely, combines a balance of refuge for safety and a wide visual prospect for exploration and foraging."5Edward O. Wilson, The Future of Life (New York: Vintage, 2003), 135. Yi-fu Tuan phrases the balance more elegantly: "Place is security, space is freedom: we are attached to the one and long for the other."6Yi-Fu Tuan, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977), 3.

|

| Start of the raised vegetable bed, with Virginia bluebells lining the path, Carolina silverbell and wildflower patch with Trillium cuneatum in foreground, Alabama snow-wreath left of the bench, and Rhododendron 'Maxecat' at bottom left corner. Birmingham, Alabama, March 30, 2008. Photograph by Jon Smith. |

From the start, and quite unavoidably (given the glory of the site), I imagined my garden as site-specific art, a celebration of both place and space. What I wanted—my wife, far the more experienced gardener, ceded the yard to me, as I was obviously obsessed with it—was a seamless transition from the retro-modern ambience of the house to the woodlands above: a garden that would understand and embody "seeming oppositions as sustaining relations."7Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002), 166. The hardscape of the yard made achieving this goal much easier: near the house rose a series of whitewashed terraces, their walls still in good condition, with a set of concrete steps heading up toward the gate in the chain link fence. But the steps stopped about two-thirds of the way up; here there were still terraces, but separated by slopes rather than walls, and the path curved around to the right before angling back up the slope to the gate. Outside the gate, the natural curves of the hillside had remained, and we discovered a lush, level area with a limestone outcrop just below the footpath. When we moved in, all of this was overgrown with vines and all the invasive (sometimes botany employs political discourse, too) non-native species mentioned above—mercifully minus kudzu but plus mimosa. Our discovery that the fence even had a gate was the result of an almost archaeological investigation.

Unlike my midwestern in-laws, my parents (a North Carolinian and a New Yorker) were not gardeners; to follow my "family recipe" would have been to plant a few flowering dogwoods (classic understory plants) in full Virginia sun, fail to water them enough, and watch them "mysteriously" die.8Apparently they were not alone. As the leading book on dogwoods puts it: "Take a typical understory plant like C. florida that thrives in the partly shady wood with nice rich organic soils all moist and acidic. Once the plant leaves the nursery for that long trunk ride to its new home, the game is just about over. Despite all encouragement and direction, most homeowners run right home and find the sunniest, driest, and nastiest site with the poorest excuse for soil available to them." See, Paul Cappiello and Don Shadow, Dogwoods (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2005), 32. Instead, I spent hours and hours online and poring over books checked out from the Birmingham Botanical Gardens library. When I started, I had four or five general ideas, each of which stayed with me through the process, and which I hoped to weave into a seamless whole. I wanted some plants that were native to this area, chiefly to blur the boundary between the public park behind the house and our yard, but also to begin to diversify the ecosystem in the woodland park since even the native species that had recolonized that area over the past half century were still far less diverse than what had once been there. (I also wanted plausible deniability since I was, in a few places, planting on city property, practicing what David Tracey and Richard Reynolds, among others, call "guerrilla gardening.") I wanted to attract and sustain birds, butterflies, and other wildlife, and I had a certain fantasy, drawing on German Schrebergärten and English garden allotments, of the kind of public European footpath that people garden right up to. Second, I wanted plants that reminded me of Appalachian and Piedmont Virginia as much as the site itself did: the classic exile's garden.9For what is quite possibly the definitive treatment of diasporic gardening, see Sarah Casteel's remarkable recent book Second Arrivals (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2007). Third, since the house, with its wide eaves and long, low midcentury-modern form, drew on a vaguely East Asian stylistic language, near it I wanted plants with a Chinese or Japanese provenance—daphnes, gardenias, camellias, lacecap hydrangeas. (While there were several evergreen azaleas already on the property, however, I was not tempted to add to their number.) Fourth, somewhere under the power-line easement out back where I could see it from my study window, I wanted a small, tropical-looking area full of huge leaves and bright color all summer. Part of this was my nod to the more irreverent and ebullient traditions of African American southern gardening and yard art; part, too, was my nod to global warming, since, defying stereotypical notions of unchanging "place," Birmingham has rather firmly moved in the past fifteen years from USDA Zone 7 to Zone 8.10On December 19, 2006, the National Arbor Day Foundation—hardly a political organization—published, based on the past fifteen years' climate data, its independent revision of the USDA's 1990 map of climate hardiness zones (arborday.org/media/zones.cfm), reinforcing what gardeners had been experiencing—"on the ground," as it were—for some time. I have invested a significant part of my career arguing for certain shared features of the United States and global Souths, and in addition I did want a small eruption of Martha Schwartz-y "artificiality," even if only in the form of decidedly "out of place" shrubs and perennials, since, for example, the bright-orange plastic garden bench in the Design Within Reach catalog was, for two Alabama college professors, not within reach at all. Hence cannas, Formosa lilies, ginger lilies, Hydrangea aspera, a bougainvillea experiment, lobelias, a deciduous Ashe's magnolia—the latter two, native but tropical-looking, to tie the tropical and native areas together. I even put in a couple of Sabal 'Birminghams,' a hardy cultivar one of whose ancestors is almost surely the cabbage palm (Sabal palmetto), the state tree of Florida and South Carolina. (Since I could only afford young plants, they simply look, even now, like large gladioli.) In the drought that ran from 2006 to the end of 2008, the worst in recorded history, when plants native to central Alabama themselves struggled, I learned to overcome my resistance to yuccas, several of which—some native to Alabama, others introduced from Mexico, whose climate we may have begun to borrow—now lend their strikingly sculptural presence to key focal points of the garden. In the late summer of 2007, I installed by my downspouts six rain barrels. Half an inch of rain yields 330 gallons, which, hand-carried up the slope, can keep my ornamental shrubs alive from two to four weeks.

|

| Young hedge of Rhododendron 'Maxecat,' piedmont azaleas to the left of the hedge. Birmingham, Alabama, April 8, 2008. Photograph by Jon Smith. |

Insofar as the garden abutted a public pedestrian thoroughfare, what I wanted, too, was a sense of surprise for those pedestrians who happened upon it. Though polemical, Lucy Lippard's definition of public art as "accessible art of any species that cares about, challenges, involves, and consults the audience for or with whom it is made, respecting community and environment" is helpful here.11Lucy Lippard, The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society (New York: The New Press, 1997), 264. Frankly, as a modernist I'm not much concerned with accessibility, and, at the risk of sounding overly literal about it, most people seeing the garden from that direction will have had to walk at least half a mile to do so. My garden—small-scale art for the long haul, as Lippard would say—is inevitably about motion too. For now, the footpath behind it serves as an unmarked spur of the paved Vulcan Trail. Precisely because at present the trail doesn't "go" anywhere, many of the people on it are first-timers. Six hundred yards from the paved section, after a shady stretch through invasive English ivy behind our neighbors', the curious come across the spray of native rhododendrons that is slowly forming a flowering evergreen screen between the trail and our property. A break in the row reveals three stone steps (edged in spring with Virginia bluebells) descending into a small garden with mountain laurel, deciduous native azaleas, bottlebrush buckeyes, Alabama snow-wreath, smooth and oakleaf hydrangeas, American beautyberry, a sourwood and a silverbell tree, atamasco lilies defining the curve of a limestone outcrop, Stokes' aster, foamflower, Indian pinks, a few trilliums (T. cuneatum) that were already on the site, and a host of other small native flowers gleaned from Jefferson County's annual landfill digs. Closer to the terraces are my wife's rosebushes (increasingly shaded out as the woods behind continue to grow) and a pair of fastigiate Graham Blandy boxwoods mock-pretentiously guarding the gate in the chain-link fence. In future years, I'd hoped to make the footpath truly pass through, instead of just alongside, a subtly landscaped area, with redbuds, dogwoods, red buckeyes, and, someday, American chestnuts all brightening the woods above the trail. Ideally, people would not realize the area is landscaped at all.12Louise Wrinkle's Mountain Brook garden, often cited in works like Sally Wasowski with Andy Wasowski, Gardening with Native Plants of the South (Boulder, CO: Taylor Trade, 1994), is a model here, or was until she paved her creekside walkway with asphalt. (In some cases, creating such an illusion is not difficult because people are not always very observant. In 2004, a group of non-neighborhood-residents calling themselves "Friends of the Vulcan Trail," on an annual and officious "trail-clearing" mission, veered several yards off the trail to destroy two of my rhododendrons, not to mention a small tree belonging to one neighbor and a mahonia belonging to another.) But the real impulse behind this sort of restorative gardening is what Ken Druse calls "giving back" in The Passion for Gardening: Inspiration for a Lifetime (New York: Clarkson Potter, 2003), 97–143. It's a different aesthetic and ethic from Schwartz's, which I deploy elsewhere in the garden. (Why choose?) Schwartz, notes Tim Richardson, "does not try to manipulate the natural landscape in a subtle way, bending it to her ends by using nature's own palette of trees, shrubs, and flowers. For Schwartz, such an approach is lazy or even dishonest, since her argument is that even the notion that unsullied 'nature' exists out there is patently false," see Tim Richardson, ed., The Vanguard Landscapes and Gardens of Martha Schwartz (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2004), 7. Like most dogmatism, such orthodox postmodernism can overstate its point. Habitat restoration, subtly aestheticized or not, isn't about pretending unsullied nature exists, it's about ameliorating some of the sullying.

|

| Workers clearing powerline easement, Hydrangea arborescens 'Annabelle' in foreground. Birmingham, Alabama, July 5, 2007. Photograph by Jon Smith. |

Two steps inside the gate in the fence, just where the natural curves of the mountainside give way to the terraced slopes planted with hydrangeas and brugmansia, hellebores and ginger lilies and crested iris, a previous owner—I could never have done this—had bolted through the trunks of two young pine trees to create a frame for an outdoor swing, though when we moved in no swing hung from the 4x4s fixed there. We purchased by mail and assembled one made of—globalization strikes again—sustainably harvested teak. And it is here at night, especially in winter when the mosquitoes are gone and the view is unobstructed by oak leaves, that we will sit and look out over the city of a million people in which we live. Often I can see the glow of my computer monitor through the study window; from the roof above it, the DSL connection over which most of the plants in this garden were researched and ordered runs up the telephone line to the row of poles behind us. This is where I most want to sit, the most liminal place in the whole liminal site. My physical pleasure—visual, auditory, and tactile—in the urban space is inseparable from my pleasure in the place from which I view it. And this latter pleasure is complex.13Partly because of gardening's perceived distance from urban youth subcultures and electronic media, no scholarly cultural studies treatment of its pleasures exists, and the afterword below is not intended to fill that void. For an impressionistic meditation intended to "inspire" other gardeners, see Druse, The Passion for Gardening. Like the bodily pleasure of swing dancing noted by V. Vale, it's been partly the pleasure, after hours each week in front of that monitor (and of students!), of hauling eighty-pound chunks of sandstone to make steps, of spreading compost, of planting and tending mountain laurel and silky stewartia (the latter, I confess, unsuccessfully).14V. Vale, Swing! The New Retro Renaissance (San Francisco: RE/Search Publications, 1998). Yet it is not and, unlike swing dancing, has never been, hip, and while I tend to buy my plants not from big-box chains but from smaller local nurseries or places like Woodlanders in South Carolina (for southeastern native plants), or Greer Gardens in the Pacific Northwest (for rhodies), or several of the edgier nurseries run by globetrotting "plant hunters" (Plant Delights, Yucca Do, or Heronswood when it was run by Dan Hinkley), it isn't consumption as protest. In fact, despite a significant cash outlay, it's not really reducible to consumption, any more than the pleasure of running is reducible to the pleasure (or hassle) of buying running shoes. And though I have consulted gardening books from the 1940s, 1950s, and early 1960s, even laying out a garden incorporating plant combinations and design philosophies favored in those decades does not feel like wearing vintage. As separate, living organisms (i.e., as the Real), all but the most ancient individual plants resist the artifactuality, perhaps even the implicit narcissism, of a skinny tie or, for that matter, a postwar Danish credenza.15"I wonder," asks Tom Rooks, a landscape designer in Michigan extensively quoted by Druse, "what do people do who are in love with things that are completely man-made? Like people who are in love with cars? What we're in love with is so complex and so never-ending, you can never feel you've done everything or learned everything about it." Druse, The Passion for Gardening, 22. Druse's own metaphor that nature is "the senior partner in this collaboration" is schmaltzy but accurately depicts the basic ontological sense that gardening can resist fetishism. Ibid., 232.

Even ten years ago, most critics of southern culture—ignoring the DSL connection and the urban setting—would have discussed my garden labors, if pressed, as evidence of my southern "sense of place," my "attachment to the land," and so on. Confusing me, perhaps, with Walker Percy, others might alternately have read all this as tragically "post-southern": removed from the land of my ancestors, thrust into a world of postmodern space, I desperately attempt to reestablish connection, to re-create place. Conversely, many postmodern geographers, still under the spell of what Edward Soja happily calls "the Edge City maxim, that every American city is growing in the fashion of Los Angeles," would have simply ignored the site, and potentially all Birmingham's parks as well, considering Birmingham, if at all, as a kind of poor man's or proto-Atlanta, itself a kind of poor man's or proto-Los Angeles of simulacra and abstract capitalist space.16Edward W. Soja, Postmetropolis: Critical Studies of Cities and Regions (Madden, Massachussetts: Blackwell, 2000), 401. For the classic postmodern-geography treatment of Atlanta, see Charles Rutheiser, Imagineering Atlanta: The Politics of Place in the City of Dreams (New York: Verso, 1996). Neither approach suffices.

Afterword: The View from British Columbia

In 2010, my wife and I moved to North Vancouver, British Columbia. By 2012, our Birmingham garden was no more. We had been unable to sell the house in the depressed US market, and the folks to whom we were able to rent it were lovely people but in no sense gardeners. (Nor could we have expected them to be.) Scores of plants, including virtually all the rhododendrons, died from lack of watering; others were shaded out by weeds. To make matters worse, sometime in early 2012, a crew from the city of Birmingham came down the trail with a backhoe on some sort of trail widening mission, got the backhoe stuck, and destroyed many more plants in the process of extricating it. For no apparent reason, they also went twenty feet out of their way to cut down my sourwood tree, which had gotten about twelve feet tall. A few plants—generally, those native not simply to "the South" or Alabama, but to Jefferson County in particular—do still thrive back there. The Alabama snow-wreath I planted by the limestone outcrop likes the location so much it has suckered all over the place, almost blocking access to the path. The Piedmont azaleas, bottlebrush buckeyes, oakleaf hydrangeas, and three cultivars of Hydrangea arborescens are all still there, if you know where to look. But for the most part, the garden has been swallowed back up into the mix of invasive plants and second-growth forest that was there before I started the project. Inside the fence, meanwhile, most of the non-native hydrangeas are gone. In fact, when we do put the house on the market next year, we've been told we will have to do considerable work just to restore its "curb appeal."

Part of me wants to interpret all this metaphorically, to read my desiccated, neglected garden as a slightly accelerated version of the Deep South as a whole, whose fate in fifty years as a result of anthropogenic global warming is on track to be, in a single word from NASA climatologist James Hansen, "desertification." After all, how easy it would be—and, I argue in Finding Purple America, how unethical—to fall into pleasant, moralizing tears over my garden as a figure for such a loss, to adapt old southern studies' endlessly replicable melancholia to yet another Lost Cause! Conversely, how easy to lay, from the safe distance of western Canada, the problem at the feet of "the South," so that the whole mess could be attributed to those pickup-driving, coal-burning yahoos, the exception to some putatively eco-virtuous blue-state nation? Both narratives, however, represent their own kinds of obvious mythmaking, their own fantastic "jukeboxes" (in the terms of the book).

Instead, as soon as we got to North Vancouver, I started another garden. Among the more conventional roses, peonies, dahlias, and crocosmia, it contains what may be the only longleaf pine seedling in British Columbia.

About the Author

Jon Smith is associate professor of English at Simon Fraser University. He is the coeditor with Deborah Cohn of Look Away! The US South in New World Studies (Duke University Press, 2004) and the author of Finding Purple America: The South and the Future of American Cultural Studies (University of Georgia Press, 2013). He has been a certified master gardener in Alabama and is currently one in British Columbia.

Recommended Resources

Text

"New Birmingham Ordinance Encourages Urban Gardens." WBRC, April 30, 2013.

http://www.myfoxal.com/story/22123015/new-birmingham-ordinance-encourages-urban-gardens.

Smith, Jon. Finding Purple America: The South and the Future of American Cultural Studies. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2013.

Sultana, Selima and Joe Weber. "Journey-to-Work Patters in the Age of Sprawl: Evidence from Two Midsize Southern Metropolitan Areas." The Professional Geographer 59, no. 2 (2007): 193–208.

Wasowski, Sally with Andy Wasowski. Gardening with Native Plants of the South. Boulder, CO: Taylor Trade, 1994.

Web

Birmingham Urban Garden Society

http://bugs_people.tripod.com/BUGS/.

Jones Valley Teaching Farm

http://jonesvalleyteachingfarm.org.

USDA PLANTS Database

http://plants.usda.gov.

Similar Publications

| 1. | We now live in North Vancouver, British Columbia, but—since we moved during the Great Recession—we were unable to sell our Birmingham house. I have opted, therefore, to continue using the present tense and referring to the place as "our house," especially because we own no other: in North Vancouver, we are renters. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Olmsted Brothers, A System of Parks and Playgrounds for Birmingham: Preliminary Report upon the Park Problems, Needs, and Opportunities of the City and its Immediate Surroundings (Birmingham: Park and Recreation Board of Birmingham, 1925), 12. Reprinted by the Birmingham Historical Society, 2005. |

| 3. | Ibid., 20. |

| 4. | William Faulkner, Absalom, Absalom! In William Faulkner, Novels 1936–1940, ed. by Joseph Blotner and Noel Polk (New York: Library of America, 1990), 111. |

| 5. | Edward O. Wilson, The Future of Life (New York: Vintage, 2003), 135. |

| 6. | Yi-Fu Tuan, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977), 3. |

| 7. | Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002), 166. |

| 8. | Apparently they were not alone. As the leading book on dogwoods puts it: "Take a typical understory plant like C. florida that thrives in the partly shady wood with nice rich organic soils all moist and acidic. Once the plant leaves the nursery for that long trunk ride to its new home, the game is just about over. Despite all encouragement and direction, most homeowners run right home and find the sunniest, driest, and nastiest site with the poorest excuse for soil available to them." See, Paul Cappiello and Don Shadow, Dogwoods (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2005), 32. |

| 9. | For what is quite possibly the definitive treatment of diasporic gardening, see Sarah Casteel's remarkable recent book Second Arrivals (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2007). |

| 10. | On December 19, 2006, the National Arbor Day Foundation—hardly a political organization—published, based on the past fifteen years' climate data, its independent revision of the USDA's 1990 map of climate hardiness zones (arborday.org/media/zones.cfm), reinforcing what gardeners had been experiencing—"on the ground," as it were—for some time. |

| 11. | Lucy Lippard, The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society (New York: The New Press, 1997), 264. Frankly, as a modernist I'm not much concerned with accessibility, and, at the risk of sounding overly literal about it, most people seeing the garden from that direction will have had to walk at least half a mile to do so. |

| 12. | Louise Wrinkle's Mountain Brook garden, often cited in works like Sally Wasowski with Andy Wasowski, Gardening with Native Plants of the South (Boulder, CO: Taylor Trade, 1994), is a model here, or was until she paved her creekside walkway with asphalt. (In some cases, creating such an illusion is not difficult because people are not always very observant. In 2004, a group of non-neighborhood-residents calling themselves "Friends of the Vulcan Trail," on an annual and officious "trail-clearing" mission, veered several yards off the trail to destroy two of my rhododendrons, not to mention a small tree belonging to one neighbor and a mahonia belonging to another.) But the real impulse behind this sort of restorative gardening is what Ken Druse calls "giving back" in The Passion for Gardening: Inspiration for a Lifetime (New York: Clarkson Potter, 2003), 97–143. It's a different aesthetic and ethic from Schwartz's, which I deploy elsewhere in the garden. (Why choose?) Schwartz, notes Tim Richardson, "does not try to manipulate the natural landscape in a subtle way, bending it to her ends by using nature's own palette of trees, shrubs, and flowers. For Schwartz, such an approach is lazy or even dishonest, since her argument is that even the notion that unsullied 'nature' exists out there is patently false," see Tim Richardson, ed., The Vanguard Landscapes and Gardens of Martha Schwartz (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2004), 7. Like most dogmatism, such orthodox postmodernism can overstate its point. Habitat restoration, subtly aestheticized or not, isn't about pretending unsullied nature exists, it's about ameliorating some of the sullying. |

| 13. | Partly because of gardening's perceived distance from urban youth subcultures and electronic media, no scholarly cultural studies treatment of its pleasures exists, and the afterword below is not intended to fill that void. For an impressionistic meditation intended to "inspire" other gardeners, see Druse, The Passion for Gardening. |

| 14. | V. Vale, Swing! The New Retro Renaissance (San Francisco: RE/Search Publications, 1998). |

| 15. | "I wonder," asks Tom Rooks, a landscape designer in Michigan extensively quoted by Druse, "what do people do who are in love with things that are completely man-made? Like people who are in love with cars? What we're in love with is so complex and so never-ending, you can never feel you've done everything or learned everything about it." Druse, The Passion for Gardening, 22. Druse's own metaphor that nature is "the senior partner in this collaboration" is schmaltzy but accurately depicts the basic ontological sense that gardening can resist fetishism. Ibid., 232. |

| 16. | Edward W. Soja, Postmetropolis: Critical Studies of Cities and Regions (Madden, Massachussetts: Blackwell, 2000), 401. For the classic postmodern-geography treatment of Atlanta, see Charles Rutheiser, Imagineering Atlanta: The Politics of Place in the City of Dreams (New York: Verso, 1996). |