Overview

Lynn Weber writes about the challenges faced by Hurricane Katrina evacuees displaced to Columbia and West Columbia, South Carolina, in this essay adapted from her article "When Demand Exceeds Supply: Disaster Response and the Southern Political Economy," Displaced: Life in the Katrina Diaspora, ed. Lynn Weber and Lori Peek (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012).

|

Introduction

Before Hurricane Katrina struck in late August of 2005, the Gulf Coast states of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama had among the highest levels of race, class, and gender inequality and the worst quality-of-life indicators in the nation for their poor, people of color, and women. The extreme inequality in these states reflects a white southern legacy of a government/elite/corporate alliance that promoted slavery and the plantation system; post-slavery agricultural peonage; the convict lease system; concentrated agribusiness; and nonunion, low-wage labor.1V. O. Key, Jr., Southern Politics in State and Nation (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1949); Joel Williamson, The Crucible of Race: Black and White Race Relations in the American South (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984); Michael Goldfield, The Color of Politics: Race and the Mainsprings of American Politics (New York: New Press, 1997); Jeffrey S. Lowe and Todd C. Shaw, "After Katrina: Racial Regimes and Human Development Barriers in the Gulf Coast Region," American Quarterly 61, no.3 (September 2009): 803-827.

Strengthened during the political realignment of the 1980s, this alliance, which historically defined the white southern governing philosophy, now threatens to dominate the nation as a whole. Often labeled "neoliberal," and yet fundamentally conservative (or reactionary), this governing philosophy calls for cutting social spending deeply, including spending on welfare programs and benefits, and selling off government assets and functions to private corporations, while reducing or eliminating regulations on profit accumulation.2Lowe and Shaw; Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2007).

One outcome of the widespread application of this governing model has been rising inequality across the nation, but especially in the historically poor and racially divided South. Despite hopes that the influx of Hurricane Katrina recovery money into the Gulf Coast states would improve the status of the disadvantaged and ameliorate inequalities, the emerging consensus is that the storm and the response to it simply exacerbated these preexisting social ills.3Lowe and Shaw; Klein; Lynn Weber, "Intersectionality, Gender, and Health: What Katrina Reveals," (paper presented at Social Science & Medicine, Gender & Health Special Issue Workshop: Relational, Biosocial, and Intersectional Approaches, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, 2010); Mark M. Smith, Camille, 1969: Histories of a Hurricane (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011).

|

| Map showing route from New Orleans, Louisiana to Columbia and West Columbia, South Carolina, 2012. |

This essay presents findings from a study of Katrina evacuees' reception in Columbia and West Columbia, South Carolina. Interviews with residents, volunteers, service providers, and evacuees reveal how people coming to and living in these two southern locales—seven hundred miles away from New Orleans—responded to and made sense of the massive disaster of Hurricane Katrina and the resettlement it precipitated. When Katrina's evacuees came to South Carolina, they entered a state that had the same high levels of poverty and poor quality-of-life indicators as New Orleans and the Gulf Coast. But in part because South Carolina had more systematically and comprehensively embraced neoliberal governing ideas than had even other southern states, evacuees to South Carolina negotiated post-disaster displacement in a place where affordable housing, public transportation, and employment options are among the least available in the nation and where social welfare policies and benefits are among the nation's most restrictive, punitive, and least generous. The story of the evacuees' reception in South Carolina highlights the ways in which political, economic, and social conditions in cities and towns across the US affected their ability to respond to Katrina and the ways that the crisis itself magnified the long-term consequences of government disinvestment in such critical needs as infrastructure, social programs, and services.

I begin with a brief overview of the socioeconomic-political context of the Midlands South Carolina region, including Columbia and West Columbia, and a description of the initial reception of Katrina evacuees in September 2005. Then, after describing data collection, I analyze the reception and resettlement processes associated with housing, transportation, and social welfare benefits and the impact of these processes on the evacuees. Finally, I present evidence that the evacuees' reception in the Midlands was also shaped by, and locally understood in relation to, the region's history of race relations and its experience with other recent migrants: Latinos, Eastern Europeans, and Somali Bantu refugees.

Columbia and West Columbia, South Carolina

|

| Map showing the Midlands of South Carolina, 2012. Columbia, the state capital, and West Columbia are in the Midlands region of the state. |

The South Carolina Midlands is situated in the center of the state, less than two hours from the Upstate area of Greenville and the growing suburbs of Charlotte, North Carolina, and the Low Country, including Charleston. Columbia, the capital of South Carolina, lies in the Midlands and is the largest city in the state, with a population of approximately 123,000 within city limits and of over 700,000 for the Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA). Major employers include government, healthcare, the University of South Carolina, and the largest US Army training base in the nation, Fort Jackson.

West Columbia, a largely working-class town of thirteen thousand in adjacent Lexington County, is separated from Columbia by the Congaree River. In the early nineteenth century, West Columbia was established as a mill town that housed workers who ferried across the river to work in Columbia's textile mills, until the first bridge was built in 1827. A century of textile production in Columbia ended in 1996 with the closing of the Olympia and Granby Mills and their later transformation into apartment complexes, grocery stores, museums, and art galleries. West Columbia has become home to Columbia's growing workforce, University of South Carolina students, and young professionals and their families because it has more affordable housing than Columbia. West Columbia and its neighboring communities of Cayce and Springdale (the West Metro Area) also host a major hospital, the regional airport, and a variety of storage and distribution facilities and employers, including United Parcel Service.

|

| Map of Columbia, West Columbia, Cayce, and Springdale, South Carolina, 2012. ©OpenStreetMap contributors, CC-BY-SA. |

Table 1 presents some demographic characteristics of Columbia, West Columbia, and, where comparable data are available, New Orleans and the United States. Data on poverty and median household income for 2000 demonstrate some basic similarities among the three Southern cities. All have poverty populations ranging from 4.4 (West Columbia) to 11.3 (New Orleans) percentage points above the national median and household incomes ranging from $10,853 (Columbia) to $14,861 (New Orleans) below the national median for all groups—Blacks, Whites, and Hispanics. Hispanics in West Columbia appear to have both higher numbers in poverty and higher household incomes than Hispanics or Blacks in Columbia or New Orleans, figures that likely reflect the larger number of earners in a single household in West Columbia.

Table 1 also presents population change data based on local government surveys conducted in 2006.4Central Midlands Council of Governments, Region Report: West Metro Area, 3, no. 1 (Spring 2006), http://www.centralmidlands.org/pdf/caycewcola06.pdf (accessed February 17, 2011). The data illustrate the more rapid growth of West Columbia, increasing by 8.5 percent since 1990 while Columbia increased by only 5.5 percent. More important, in the last two decades, the population of West Columbia, as in much of the South, has undergone major transitions in race, ethnicity, and class composition—a significant increase in African Americans and in documented and undocumented Hispanics.5Center for Research on Women, Across Races & Nations: Building New Communities in the US South (Memphis, TN: University of Memphis, 2006); State of South Carolina Commission for Minority Affairs, "South Carolina Hispanic/Latino Report" (Columbia: South Carolina Commission on Minority Affairs, 2006), http://www.state.sc.us/cma/data/FINDINGS%20REPORT2006.pdf (accessed February 21, 2011); Heather A. Smith and Owen J. Furuseth, Latinos in the New South: Transformations of Place (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2006). By 2004, South Carolina's Hispanic population had the fourth fastest rate of increase in the country, and since 1990, Lexington County (including West Columbia) has consistently been among the ten South Carolina counties with the highest Hispanic population.6Brenda Vander Mey and Ashley W. Harris, "Latino Populations in South Carolina, 1990-2002," working paper (Clemson, SC: Department of Sociology, Clemson University, 2004).

| Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the United States, New Orleans, West Columbia, and Columbia | ||||

| United States | New Orleans | West Columbia | Columbia | |

| % Individuals Below Poverty, 2000 | ||||

| Total | 12.4 | 23.7 | 16.8 | 22.9 |

| White | 6.7 | 11.0 | 11.4 | 9.8 |

| Black | 23.5 | 33.8 | 33.0 | 26.1 |

| Hispanic | 22.0 | 21.9 | 32.7 | 13.2 |

| Median Household Income, 2000 | ||||

| Total | $41,994 | $27,133 | $31,000 | $31,141 |

| White | $44,687 | $40,049 | $34,558 | $39,877 |

| Black | $29,423 | $24,461 | $18,813 | $21,393 |

| Hispanic | $33,676 | $28,545 | $34,558 | $31,079 |

| Total Population * | ||||

| 1990 | 12,541 | 116,405 | ||

| 2006 | 13,604 | 112,819 | ||

| % Change, 1990–2006 | 8.5 | 5.5 | ||

| Hispanic Population | ||||

| % of Total Population, 1990 | 0.6 | 1.8 | ||

| % of Total Population, 2006 | 7.3 | 3.5 | ||

| % Change, 1990–2006 | 1116.0 | 94.0 | ||

| Black Population | ||||

| % of Total Population, 1990 | 14.9 | 45.8 | ||

| % of Total Population, 2006 | 18.6 | 45.3 | ||

| % Change, 1990–2006 | 24.8 | -1.0 | ||

| White Population | ||||

| % of Total Population, 1990 | 84.1 | 51.8 | ||

| % of Total Population, 2006 | 76.1 | 50.0 | ||

| % Change, 1990–2006 | -9.5 | -3.5 | ||

| * Sources: US Census Bureau, "Demographic Profile Highlights," American FactFinder (Washington, DC, 2000), accessed January 16, 2011, http://factfinder.census.gov/legacy/aff_sunset.html. Data for United States; Columbia, SC; West Columbia, SC; and New Orleans, LA. Since census data are not available for West Columbia beyond 2000, 2006 population data for Columbia and West Columbia are from Central Midlands Council of Governments, Complete Demographic Summary Report (2007), accessed January 16, 2011, http://centralmidlands.org/pdf/west_columbia.pdf and http://centralmidlands.org/pdf/columbia.pdf. | ||||

From 1990 to 2006, the Hispanic population in West Columbia grew by over one thousand percent, while the Hispanic population of Columbia, just across the river, grew by only ninety-four percent.7For a variety of reasons, the Hispanic population is undercounted by census enumerators. The most common factors associated with undercount of Hispanics in the census include complex household makeup or cultural differences in defining households, individual/family mobility, legal (authorized versus unauthorized) status, fear or distrust of government, and language barriers. See Elaine Lacy, "Mexican Immigrants in South Carolina: A Profile" (Columbia: University of South Carolina, 2007). Likewise, West Columbia's African American population grew by 24.8 percent, while Columbia's declined by one percent. As the presence of people of color increased in West Columbia, the white population declined by 9.5 percent, although it still constituted three-fourths of the total. Whites maintain strong political dominance, holding seven of the eight city council seats, as well as the mayoral and city-administrator positions.

The Reception of Katrina Evacuees

|

| Michael Rieger/FEMA, Hurricane Katrina evacuees board an aircraft for evacuation at New Orleans airport where FEMA had set up operations, Louisiana, September 2, 2005. |

In the weeks after Katrina hit the Gulf Coast, the South Carolina Midlands became an emergency relief center for relocation efforts. Columbia received over four thousand families, some ten to fifteen thousand people. Arriving by airplanes some ten days after the hurricane, the 2,053 evacuees to Columbia were among the last to leave New Orleans. Most had spent days in shelters or on highway overpasses before the evacuation, had left their hometown involuntarily, and had no earlier connection to South Carolina.8Bret Kloos, Kater Flory, Benjamin L. Hankin, Catherine A. Cheely, and Michelle Segal, "Investigating the Roles of Neighborhood Environments and Housing-based Social Support in the Relocation of Persons Made Homeless by Hurricane Katrina," Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community 37, no. 2 (2009): 143-154. For the first six months, the displaced were largely accommodated in hotels, but by the end of February 2006, all who remained had moved into rental houses and apartments or to Section 8 housing. Eighteen months after their arrival, eight hundred families in the Midlands area were still receiving FEMA assistance. West Columbia was the receiving site for many of the displaced both during their hotel stays and as they moved to more permanent housing arrangements.

Political leaders in South Carolina made the initial decision to receive evacuees, including the 2,053 airlifted out of the New Orleans area. Congressman James Clyburn (D-SC), the ranking African American and then the majority whip in the US House of Representatives, and Bob Coble, Columbia's mayor at the time, organized the local response, calling on about forty leaders from city government, social services, education, labor, the nonprofit sector, business, law, healthcare, and religion to meet and coordinate activities. The coalition of Midlands leaders and volunteers that emerged to manage the reception named itself South Carolina Cares. Dubbing the evacuees "South Carolina's guests," the coalition developed a model with three core elements:

- creating a one-stop point of entry/reception center-designed to address all of the "guests"' immediate needs, including making contact with family members, FEMA registration, healthcare, schools for the children, clothes, food, and legal advice and assistance

- placing evacuees in hotels and apartments paid for with private funds raised by South Carolina Cares, not in shelters

- matching hotels and individual evacuees with volunteer "hosts" to assist in the relocation.

|

| Andrea Booher, Evacuee Umberto Romero gathers food and necessities at the distribution center at the Chalmette Recovery Center set up following Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans, Louisiana, October 22, 2005. |

When Gulf Coast residents began arriving, especially the airlifted group, they were disoriented and upset, having not been told where they were being taken. Many were sick and had gone days without access to food, clean water, and regular medications for chronic conditions. All were under intense psychological strain. South Carolina Cares arranged for food to be donated and delivered to the hotels and provided shuttle buses to and from the center. The reception center operated for two months, and local agencies ran two centers for four more months. Among the people we interviewed who had worked in or had been received by South Carolina Cares, the overwhelming consensus was that the center and the initial reception were a success. People's immediate needs were met, and the evacuees were treated with dignity and respect. Research conducted during the early reception period suggested that the evacuees were largely satisfied with the social climate in the hotels and surrounding neighborhoods and with their "host" relationship, and that each of these factors had positive effects on mental health (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety).9Ibid.

Studying Katrina's Displaced in South Carolina

By 2007-2008, I had been involved for five years with colleagues in Women's and Gender Studies at the University of South Carolina in a program of community-based participatory action research in West Columbia. Because many of Katrina's displaced had been "temporarily" housed in West Columbia in 2005 and still resided there, and because the initial relocation and reception process locally had been largely deemed a success, I initiated a study of the local context of reception. How did West Columbia residents receive the displaced? And conversely, how did Katrina's evacuees experience Columbia and West Columbia?

|

| Displaced project researchers visiting a displaced University of New Orleans scholar's FEMA trailer, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2005. Lynn Weber is furthest to the left. |

Three major sources of in-depth interviews inform this project: interviews with forty-eight black, white, and Hispanic English-speaking and twenty-one Spanish-speaking community leaders and residents of West Columbia; twenty-three people who led and worked in the Midlands relocation efforts; and twelve evacuees residing in West Columbia. Interviews lasted between forty-five minutes and two hours and were conducted between May 2007 and September 2008.10Trained graduate-student research assistants and I conducted the interviews, and participants provided informed consent beforehand. All interviews were audiotaped, professionally transcribed, and coded for analysis. Details of the study's methodology are published in Lynn Weber, "When Demand Exceeds Supply," Displaced: Life in the Katrina Diaspora (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012), 84-86.

Katrina's displaced came to understand that the conditions of life and the resources available to them in Columbia and West Columbia were tied to an inhospitable history of state governance. Although Columbia is a Democratic stronghold, West Columbia is in one of the most solidly Republican counties in the state. Further, Republicans have dominated South Carolina politics since the 1960s. The state is one of the most conservative in the union. The governor's office and both branches of the legislature are controlled by conservative Republicans—a fact that has made the state a testing ground for national Republican-Party policies designed to lead the nation toward extreme conceptions of free market capitalism and social conservatism.11Laura R. Woliver, "Abortion Conflicts, City Governments and Culture Wars: Continually Negotiating Coexistence in South Carolina," in Culture Wars and Local Politics, ed. E. Sharpe (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1999), pp. 21-42; Laura R. Woliver, The Political Geographies of Pregnancy (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002).

In a state that in February 2009 had the nation's highest unemployment rate, Governor Mark Sanford, then head of the Republican Governor's Association, led the charge of southern governors to oppose President Obama's American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, better known as the stimulus bill. Twice he refused the portion of the stimulus over which he had authority, especially objecting to increases in unemployment and Medicaid benefits that the state might have to continue two years later without federal aid.12Richard Fausset, "South Carolina's Governor May Turn Down Stimulus Money," Los Angeles Times, February 21,2009; Editorial, "Courting Disaster in South Carolina," New York Times, March 30, 2009. This stance reflected a long history in South Carolina of enacting unusually punitive social welfare policies and diminishing social spending to support the poor and working classes, including investments in affordable housing and public transportation. Housing subsidies, food stamps, child welfare benefits—all paid less and/or had stricter eligibility requirements than in New Orleans. Public transportation, at least as necessary in South Carolina, was less available than it had been in New Orleans.

Housing

|

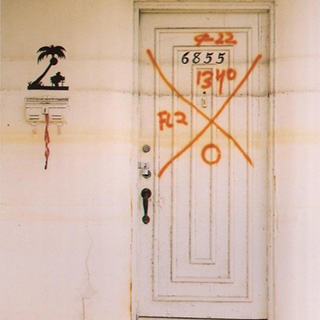

| Lynn Weber, Hurricane Katrina damage (above) and Signs about housing demolition (below), Lower Ninth Ward, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2005. |

|

Well before Katrina and before the US housing/mortgage crisis officially began in 2007, local, regional, and national housing and economic policies had contributed to a serious shortage of affordable housing along the Gulf Coast and in the evacuee receiving cities across the nation.13Sheila Crowley, "Where Is Home? Housing for Low-Income People after the 2005 Hurricanes," in There Is No Such Thing as a Natural Disaster: Race, Class, and Hurricane Katrina, ed. C. Hartman and G. D. Squires (New York: Routledge, 2006), pp.121-166. For middle class home owners displaced to South Carolina, finding temporary housing, dealing with insurance companies and the government, and deciding on their long-term housing plans were stressors that, though extreme and prolonged, were nonetheless surmountable for most. But the housing crisis was doubly intensified for low-income New Orleanians, especially the elderly and people with disabilities who had rented or lived in subsidized housing.

New Orleans and the entire Gulf Coast placed the lowest priority on rebuilding rental housing units, fifty-two thousand of which were destroyed by the storm. By 2010, five years after Katrina, all four of the city's major public housing complexes, formerly home to five thousand residents, had been destroyed or slated for destruction. Years after Katrina, tens of thousands of low-income displaced people still cannot return to New Orleans because there is no place to return to. Several of our respondents expressed sentiments similar to a thirty-five-year-old African American evacuee who had found part-time employment in Columbia. When asked in April 2008 if he had been back to New Orleans, he said, "I'm just waiting to see what the outcome's going to be. I wanna see how they rebuild New Orleans as far as the people. That's what I wanna see. Yeah, I'm just waiting for the rebuilding of New Orleans."

On the other hand, Columbia and West Columbia had an affordable housing crisis of their own that had been exacerbated by a 10 percent cut in Section 8 housing vouchers (339 vouchers) between 2004 and 2006, a cut attributed to funding formula flaws.14Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Housing Vouchers Funded in South Carolina under Pending Proposals, November 1, 2006, http://www.cbpp.org/files/11-1-06hous-sc.pdf (accessed February 17,2011). Further, in 2004, the West Columbia City Council blocked a developer's proposal to build a low-income apartment complex in the city. The developer and the National Association of Home Builders sued the city in 2005 on the grounds that the decision affected minorities unfairly. The city paid $600,000 in 2008 to the developer to settle the suit—without a requirement that the complex be built.15John O'Connor, "West Columbia Accused of Blocking Apartments," The State, February 18, 2005; Tim Flach, "West Columbia Paying Out $600.000," The State, March 4, 2008; Tim Flach, "Builders Urge More Attention to Low-Income Homes," The State, March 13, 2008.

A manager for the local housing authority described not only the situation when the displaced arrived but also its deterioration since:

South Carolina Emergency Management thought we could just go and take people in, and I said, "You've got to be kidding me." I said, "You don't understand." At that time, we had about seventeen hundred units of housing. Maybe about 1,650 is what we had gotten down to, but we were seven hundred units down [from demolition/rebuilding projects in process]. We had about five thousand on our waiting list at that time [2005], and my waiting list right now, as of January 14, 2008, just hit ten thousand. So I've got about five thousand units of housing that I can either do through the voucher or the public housing program, but a waiting list of ten thousand. So it's the highest in the thirty years I've been here. It's gonna be three to four years if you apply today.

|

| Columbia Housing Authority, Cayce public housing, Cayce, South Carolina, 2012. |

Evacuees living in public housing in New Orleans were eligible for public housing in South Carolina. But eligibility and availability are two different things. And many people cannot afford housing officially designated as "affordable." In 2006 the fair market rent for a two-bedroom apartment in South Carolina was $615 per month. The wage necessary to afford this two-bedroom apartment was estimated to be $11.82 per hour for a person working a forty-hour week.16Child Welfare Leagues of America, "South Carolina's Children 2008," http:// www.cwla.org/advocacy/statefactsheets/2008/southcarolina.htm (accessed February 17, 2011). Yet with the exception of registered nurse, the eight highest-growth jobs in South Carolina that year were unlikely to provide full-time, year-round employment. And five of those eight high-growth jobs—food prep and serving workers, waiters and waitresses, janitors and cleaners, retail salespeople, office clerks—provided wages below $11.82 per hour.17South Carolina Department of Commerce, "High-Growth Jobs in South Carolina: Labor Market Information," July 2008, http://www.workforcesouthcarolina.com/media/3163/highgrowthjobs072008.pdf (accessed February 21, 2011).

Beginning in fall 2005, FEMA periodically issued lists of families still eligible for housing assistance. Each time the lists came out, some families were left off even though local caseworkers and the displaced themselves knew they were still eligible. In September 2007, two years after their displacement, eighty families in the area still received housing subsidies. After having demonstrated a continued need for housing assistance and having re-qualified several times, these remaining families were told that they were going to be "weaned" from subsidies over the next eighteen months. Beginning in March 2008, the families were asked to pay $50 toward the monthly rent and to increase that amount by $50 per month up to $250 or one-third of their gross monthly income. By April 2008, the rolls had been reduced from eighty to forty families. While most were still in apartments, some found individual homes to rent, one a trailer, and one a Habitat for Humanity home. Ten moved to HUD foreclosure homes, living rent-free but with the possibility of removal at any time without notice. And some, facing eviction, returned to New Orleans to uncertain employment and housing options.

All of the evacuees we interviewed lived in Section 8 apartment complexes in West Columbia. And all but one were concerned about their long-term ability to afford to stay in the apartment, especially as their contribution to the rent was to increase. People with disabilities and on fixed incomes lamented that they paid higher rents in Columbia than in New Orleans. According to one white woman, even though she and her husband, both living with disabilities, liked the apartment in West Columbia, the rent was $650 a month—more than double what they had paid in New Orleans. As long as the FEMA or the Katrina Disaster Housing Assistance Program (KDHAP) emergency housing programs were paying the rent, she was satisfied. But at the time of her December 2007 interview, the "weaning" plan had begun. Several months later she and her husband had been evicted and had returned to New Orleans after housing assistance ran out.

In March 2008, three months after an initial interview, one of our research team members talked with another respondent at the homeless shelter in Columbia. A middle-aged white man who had had great difficulty finding employment, he was also evicted when full housing assistance ran out. In New Orleans, he had worked in a laundry for a homeless shelter. He described his plight and what he saw on the horizon for the nation:

I worked there in the daytime. I'd get up at 5:00, going to work 5:30, get done at 4:00. I would do the laundry for the homeless. I never thought of me being homeless, never, and yet I lost my house because the insurance company wouldn't cover it. . . . [I've] never been homeless, and it shocked me. I always had a good job. I had three jobs and that's all gone. It wiped it all out. I believe with all this banking crap that happened, there's gonna be a lot of people out of work, a lot of people, and where are they gonna put 'em?

Transportation

Critically needed in West Columbia, public transportation is abysmally inadequate. A United Way needs- assessment in 2004 cited transportation as the most significant barrier to health and human services in the Midlands.18United Way of the Midlands, Facing Facts: United Way of the Midlands Update for 2004: A Study of Issues That Shape Our Region (Columbia, SC: United Way of the Midlands, 2004). In 2002, the Central Midlands Regional Transit Authority (CMRTA) was created as a public entity to manage and operate bus and paratransit services. At the time, projections were that it would not be fiscally solvent after 2009 without significant infusions of funds from local governments of Richland County, including Columbia, and the West Metro Area.19Shalama Jackson, "Lexington County—Public Transportation Dilemma—Bus Service Cuts Thwart Disabled," The State, February 2, 2007; Shalama Jackson, "Funding the Transit System: Low Ridership Might End Services-Lexington County," The State, June 5, 2007.

In 2006, facing drastic cuts, the CMRTA unsuccessfully petitioned city and county governments in Columbia, Richland County, and the West Metro Area for a dedicated source of funding from each municipality. By 2008, reduction in bus routes brought low ridership, since the few routes remaining were not workable for those who most needed them. West Columbia's mayor and city council cited the low ridership as evidence that the service was "not needed" and as justification for continuing to opt out of CMRTA support.20Ibid.

For Katrina's displaced, transportation posed major problems. A middle-aged woman with disabilities described her lack of familiarity with West Columbia and the transportation obstacles confronting her:

Oh, it changed a lot 'cause when I was in New Orleans, I could get out. I know New Orleans like I know the back of my hand. Here I don't unless I got a way to get around, and that I don't have. Unless I pay five dollars for a cab—five dollars I don't have all the time. See, some people can get a ride for nothing. I can't unless I come up with some money . . . and I can't afford it.

Others echoed her frustration: "We don't have no transportation." "I travel much further to go to work." "Here it's too hard to find a job 'cause the stores and everything are two miles away." " . . . everything is spread out, and the bus service sucks."

|

| Central Midlands Regional Transit A Bus Routes, Columbia, South Carolina, and surrounding areas. West Columbia, South Carolina, the area to the west of the Columbia River, is underserved by the metropolitan region's public transit system. |

|

| New Orleans Regional Transit Authority system map, New Orleans, Louisiana, and surrounding areas. In contrast to the New Orleans public transit system, the Columbia, South Carolina system "was an absolute nightmare" for many Hurricane Katrina evacuees. |

Service providers in the Midlands heard that story many times. One described the biggest challenge facing the displaced as "public transportation . . . everything is so spread out. We're not a major city. We're a large town in a rural state. And we don't have—get on the bus for seventy-five cents and go everywhere you need to go." A housing authority worker said:

That was the biggest complaint that we had from the clients in that they were so used to the New Orleans transportation system that coming here was an absolute nightmare. They couldn't believe that there were so many areas that they had no transportation to get to. You'd go and find a place to live, but . . . you'd be stranded out there.

We had one client one night who was staying in a hotel out by the airport [West Metro Area]. He was a computer programmer. He got a job with Blue Cross/Blue Shield. . . . Of course, that's twenty-five miles or twenty miles or whatever, which required two different bus transfers. . . . So evidently, he got off on Two Notch Road at the wrong bus stop and had no idea where he was—had nobody he knew he could even call. . . . It was like in October or November, and it was cold, and a policeman finally stopped and said, "Where are you?" He had that nervous breakdown, all of a sudden it just came crashing on him.

The transportation problems for evacuees were so extreme that one who had a car and a job, began fighting local authorities to increase bus service to the West Metro:

I'm trying to help to fight for the bus line to get back here. . . . There is no buses back here at all for these poor people. And how do you take a bus off a line that goes to a hospital? So they got two buses come back here twice a day, early in the morning and then from four to seven at night. So that's what? That's two trips per bus.

A self-described "old rebel" who began his commitment to community activism in the civil rights movement of the 1960s, this evacuee earned the title of "Mayor" when he and others lived for months in hotels, because of the way that he advocated for and with them. He became particularly adamant about access for people with disabilities, some of whom miss work because there are too many wheelchair riders for the spaces on the bus and the routes run too infrequently.

The lack of public transportation drastically changed the lives of the chronically disabled who require regular medical visits. One evacuee needed dialysis three times a week in a place that could not be reached by bus from his home, requiring a fifty-dollar cab ride. Missing treatments because of the lack of transportation, he was forced to visit the emergency room several times. An elderly African American couple, both living with disabilities, described becoming very isolated and depressed. "Getting around," they said, was the hardest thing about Columbia. We “can't get around." They described typical days as sitting in the apartment. They could not afford to return to New Orleans and wondered what would happen when the rent subsidies ran out.

The lack of public transportation also made finding employment especially difficult for low-income displaced. Single mothers seeking work lacked affordable, accessible childcare. In New Orleans, those who lived in particular neighborhoods for years had many more options. One caseworker described a client's difficulties that she said were characteristic of several others:

This woman lives in an apartment complex, and behind her complex, she can literally walk her kids to daycare. She works at a hotel that is within walking distance. She has a neighbor who helps her watch her kids when she has to work late. But her income doesn't cover living expenses for herself and her four-year-old daughter. She already works full-time and overtime when she can. If the woman moves closer to less expensive child care, transportation to her job becomes an issue. No aid is available from any source to address clients' needs for transportation to employment.

Social Welfare and the Safety Net

Since all Deep South states share high poverty rates, low socioeconomic status, and poor health, evacuees who were welfare recipients in New Orleans expected to receive similar benefits when they applied in South Carolina. What they soon realized, however, was that South Carolina—in part because of its extremely conservative, neoliberal economic and social policies—is much more restrictive than New Orleans. A recent study of public assistance in South Carolina summarized the state's harsh position on welfare:

South Carolina's Family Independence Program [FIP, its TANF program] is one of the strictest, least generous, and most work-oriented welfare programs in the country. While most states have adopted the federal five-year time limit on assistance, South Carolina imposes time limits of 24 months of participation in a ten-year period and five years in a lifetime. . . . After the fourth month of employment, only the first $100 in monthly earnings is disregarded; beyond that, benefits are reduced by 32.4 cents for each additional dollar. The meager benefits levels, low disregard, and high reduction rate mean that families lose their eligibility for cash assistance after earning just a small amount of money.21David C. Ribar, Marilyn Edelhoch, and Qiduan Liu, South Carolina Food Stamp and Well-Being Study: Transitions in Food Stamp and TANF Participation and Employment among Families with Children (United States Department of Agriculture, April 2006), http://hdl.handle.net/10113/32788 (accessed February 16, 2011).

In 2005, the maximum monthly benefit for a family of three with no other income was $241 per month. FIP benefits in South Carolina are so low that a family of three with full benefits and no other income qualifies for the maximum food stamp allotment—$349.22Ibid. In 2003, a family of three receiving only FIP and food stamps was at 27.8 percent of the federal poverty level. No child support is provided for FIP recipients, and benefits are disallowed for children conceived while a parent receives FIP. South Carolina ranks fiftieth in per capita child welfare expenditures per month and forty-sixth in overall child welfare.23Child Welfare Leagues of America, "South Carolina's Children 2008," http:// www.cwla.org/advocacy/statefactsheets/2008/southcarolina.htm (accessed February 17, 2011).

As a result of the confluence of limited funding, strict qualification criteria, and a high poverty population, there were already long waiting lists to obtain subsidized housing and welfare benefits in South Carolina. "The Mayor," active in advocating for mass transit, recounted problems with people who resented the Katrina evacuees' preferential treatment in welfare services—even if the services were for only a short time:

A lot of people here was upset with us because they felt that we were getting treated, getting treatments that they should've gotten. . . . like far as for housing and stuff like this. Far as for food stamps, some of these people had been on the list for months and months and months and years and years.

Having to re-qualify without documentation and personal records and doing so in a state that provided less support meant that many evacuees on public assistance had much more difficult experiences than in New Orleans. "I'm having problems about my food stamps," said one disabled woman, as she compared her experiences:

And then sometimes I have it hard paying my utilities because I have so many bills to pay. This month paying all my bills doing everything, I had seventy dollars left to go a whole month on. I cannot go on just seventy dollars. I need help with that. I've called these organizations, a lot of them say we don't have the funds for this, we don't have the funds for that, but I'm trying to do the best I can, you know. So I'm trying to get somebody to help me with my utility bill.

. . . Back in New Orleans I was getting the same thing on SSI [Supplemental Security Income] that I'm getting now, but I was getting more food stamps, see, and I'm not getting it here . . . I feel if we're disabled, why don't you pay our utility bills for us because you know we can't do it out of that small little check and try to pay rent too. We can't do it.

Two case managers expressed shock at how much assistance some evacuees had received in New Orleans. Their comments illustrate the go-it-alone orientation that guides the state's programs:

South Carolina is not so forthcoming with saying, "Here's your welfare check. Here's your food stamps." I mean we had a lot of people who received assistance in New Orleans and were not able to get it here because they didn't meet the criteria under South Carolina's laws.

They received a ridiculous amount of money in food stamps, and then they come here and there's—the criteria is very different . . . and it was like, "Okay," and . . . I mean, I'm looking at them thinking, "What prevents you, really, from getting a job?"

West Columbia in Transition

Besides negotiating difficulties of housing, transportation/spatial location, and social services, evacuees to West Columbia entered a large town undergoing significant change in its racial and ethnic makeup—rapid growth of the Latino, mostly Mexican, population, and increases in the African American population and in young white and black families. In our interviews with West Columbia leaders and residents, these changes were characterized as unsettling by some, a challenge by others, and a welcome addition by still others.

Although Katrina's displaced to West Columbia were almost solely black and white United States citizens, many of West Columbia's leaders framed their perceptions of Katrina evacuees in the context of recent working-class and low-income migrants from Mexico, Central America, Russia, and Somalia. In many of their comments, they made connections between the ability and desire of West Columbia to incorporate new migrants and the perception of strains on an already stressed social infrastructure. In the words of a white woman adult education teacher:

I think people get along fairly well, but I think there's a clearer line between African Americans and whites. . . . Some of the older community are very much not liking the growth of the Hispanic population. . . . I think, again, the older population is resentful for maybe the shift in the population and perceived problems the shift has brought, and they [Hispanics] have brought shifts, and they've brought a need for infrastructure in the sense of federal housing, more use of the hospital system, more department of social services—and those entities promptly have been stretched or challenged with the movement of the population. . . . All in all, the shift will help; it'll help the community grow—and change isn't bad. . . . But it does tax your infrastructure if it's not prepared to handle it.

Others said that Hispanics were not accepted as they "should be" and that they were struggling. West Columbia natives put these struggles in a national context, arguing that the problems are not just local ones. Like many cities, West Columbia is experiencing a transnational migratory stream that is affecting the local society in many ways. As an extension agent, herself mixed-race, described it:

I'll tell you who exactly is working in the West Columbia Wal-Mart are Russian immigrants. . . . They do all the cleaning and the maintenance. They come in in crews. So there's a strong Russian population in West Columbia. I don't know where they're living. I wasn't aware of that at all. He [my husband who manages a Wal-Mart] said they did speak English . . . but they would spend the night at Wal-Mart cleaning, buffering the floors . . . because you don't have to be able to speak English to buffer floors. So that's definitely a competition for the Hispanic market and anybody that's looking for a minimum wage job.

Few people knew about Russian immigrants in West Columbia. Most were aware, however—because their relocation to South Carolina received so much media attention—that 125 Somali Bantu families were resettled in West Columbia and its neighboring communities in 2004, as part of a US State Department plan.24Jenny Burns, "No Pressure: Bible Belt Families Welcome Muslim Refugees,"The State, March 12, 2004; Joy Woodson, "Open Arms Missing to Greet Refugees: Sponsors Lacking as Charities Welcome Persecuted People to New Lives in Columbia," The State, August 24, 2006; Joy Woodson, "Yesterday's Refugee, Tomorrow's Architect," The State, April 20, 2007. West Columbia and Cayce were among the few locations in the country (including Holyoke, Massachusetts) actually opposed to their resettlement.25"Federal Agency Calls Off Bantu Resettlement in Cayce," The State, October 9, 2003; "US City Refuses to Admit Somali Bantu Refugees," The State, October 13, 2003.

This resistance remains vivid in the minds of leaders in West Columbia, most of whom were not involved in the opposition but who felt the negative publicity was a problem. When discussing how West Columbia would receive Katrina’s displaced, over one-third of local leaders compared the displaced either to the Bantu or to the much larger Hispanic migration or to both.

When we asked about the challenges posed if Katrina's displaced chose to remain permanently in West Columbia, comments such as the following, which came from a white male director of a school program, were common:

We made it through the Bantu and life went on, so same here. . . . The challenge is that we already have a plate full of those with social services needs, and I'm sure some people say well, why do I want to bring more of that into my area? What for? We have enough problems.

While local leaders pondered the strain on social services, the evacuees in West Columbia had daily contact with Latino migrants, many of whom lived in the same apartment complexes. Yet this contact did not lead to mutual understanding and support—in large part because language and cultural barriers made communication impossible. Only one of the twenty-one Latinos we interviewed had any knowledge of or contact with Katrina's displaced—because he cleaned in a hotel where many evacuees resided.

Even in the same apartment complex, the isolation felt by Katrina's evacuees seemed heightened by the presence of Latinos, whom they could not understand. One African American couple, lamenting their isolation from familiar people and places, discussed how the presence of Hispanics heightened their feeling of being "cut off" in West Columbia. When asked about friends they had made, the husband said they hadn't made any: "Most people around here is Spanish. They say 'Hey' and move on." A similar response came from a white male evacuee: "Making friends? I don't know nobody around here. . . . They're all Mexican."

The Continuing Disaster

Since the political realignment of the 1980s, the South has led the nation in implementing the conservative economic and social policies that now largely structure the conditions of life across much of the United States. Southern states have vigorously embraced these policies: privatization/outsourcing of government functions, reduced taxes, especially on the wealthy, deregulation of business, and deep cuts in social spending. South Carolina has been more aggressive than even other southern states in reducing taxes, limiting infrastructural supports for public life, and severely restricting and dismantling social welfare programs. Consequently, the most vulnerable of Katrina's displaced found West Columbia and Columbia, South Carolina, to be a particularly harsh environment.

In expressing concern about strains on the infrastructure and social services, many West Columbia natives framed their response to the Katrina evacuees in the context of Somali refugees and Hispanic immigrants. In addition to experiencing difficulties in making a life for themselves in West Columbia, the evacuees also met resentment from some of the local poor, whose wait for housing and social services was extended because the evacuees received priority.

In part because they recognized that the federal government was failing in its response to Katrina, people in the South Carolina Midlands worked hard to provide a welcome for their "guests." Hundreds of people volunteered, and local leadership committed not just to receive the displaced people of Katrina, but to do so with respect—to contradict the disrespect and inhumane response of the federal and state governments. But because volunteer work cannot be sustained for extended periods, the basic needs of healthy and thriving communities—jobs, healthcare, housing, transportation—cannot adequately be met without reliable, substantive, and ongoing government engagement.

|

| Illustrator's depiction of the Midlands Housing Alliance Transitions Center, 2011. |

The most destitute of Katrina's survivors displaced into the Midlands' social, economic, and political landscape made visible the harshness of the economic and social policies embraced by South Carolina's political leadership as well as the extent of existing social needs. When hotel rooms, meals, and clothes were made available to the displaced, people already homeless in Columbia showed up too. The heightened awareness of existing problems and the success of South Carolina Cares led a coalition of business leaders and homeless advocates to propose a $15 million center for the city's approximately sixteen hundred homeless that is modeled on the Katrina reception center. Although they faced substantial political opposition—particularly around the proposed location—the new, multiservice Transition Center opened in 2011.26Adam Beam, "Group Plans 15 Million Dollar Homeless Center," The State, June 26, 2008; Adam Beam, "Neighbors to Fight Homeless Shelter," The State, October 5, 2008.

The experiences of Katrina's displaced in South Carolina highlight the ways in which conservative social and economic policies have rendered our cities incapable of dealing with the ongoing needs of poor populations and have weakened our infrastructure and support networks. Because they are unequipped to deal with their own poor, Deep South cities are not equipped to deal with displaced disaster survivors for an extended time. Despite the phenomenal outflow of generosity, time, and expertise from individuals to international aid groups, Katrina remains a disaster—for both the poor still in New Orleans and the poor in the Katrina diaspora.

Acknowledgments

|

| Map of research locations of contributors to Displaced: Life in the Katrina Diaspora. Lynn Weber conducted research in Columbia, South Carolina. |

This article is adapted from "When Demand Exceeds Supply: Disaster Response and the Southern Political Economy," Displaced: Life in the Katrina Diaspora, ed. Lynn Weber and Lori Peek (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012), 79–103. Thank you to the University of Texas Press for permission to publish this piece.

In addition to recognizing the important and multifaceted assistance of the SSRC Research Network in providing feedback at all phases of this project, I wish to thank the graduate assistants who worked tirelessly on these research projects. For conducting interviews, Steve Hardin, David Asiamah, Manju Tanwar; for coding, data analysis, and other research, Jenny Castellow, Beth Fadeley, Uma Kandasarny, Christina Griffin, Joanne Rinaldi Stevenson. Finally, I greatly appreciate feedback on the manuscript from the Women's and Gender Studies core faculty reading group and especially from DeAnne Messias, who gave me advice throughout the process.

This research was partially supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant CMMI-0623991. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

About the author

Lynn Weber is professor of psychology and women's and gender studies at the University of South Carolina in Columbia. She is co-editor with Lori Peek of Displaced: Life in the Katrina Diaspora (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012), from which this essay is adapted.

About the Katrina Bookshelf Series

|

The University of Texas Press is proud to introduce the Katrina Bookshelf Series, Kai Erikson, Series Editor.

In 2005 Hurricane Katrina crashed into the Gulf Coast and precipitated the flooding of New Orleans. It was a towering catastrophe by any standard. Some 1,800 persons were killed outright. More than a million people were forced to relocate, many for the remainder of their lives. A city of 500,000 was nearly emptied of life.

If measured by the number of lives it claimed, Katrina does not qualify as the worst disaster in our history. But it was far and away the most destructive disaster in our national experience when one considers the amount of damage it did not only to the physical and social landscapes of the Gulf region but also to the nation more generally. And it was far and away the most telling disaster in our national experience. Katrina stripped away the outer surface of our social structure and showed us what lies underneath—a grim look at race, class, and gender in these United States.

It is crucial to get this story straight so that we may learn from it and be ready for that stark inevitability, the next time. When seen through a social science lens, Katrina is almost the perfect storm in terms of informing us what the real human costs of a disaster are and helping prepare us for the blows that we know are lurking just over the horizon.

A number of studies of Katrina have appeared since the event. Most were brief glances at some fragment of that immense disaster rather than rich, in-depth portraits of it, and many rode the crest of Katrina's celebrity for the time it was in the news. The Katrina Bookshelf Series, by contrast, is the result of a national effort to bring experts together in a collaborative program of research on the human costs of the disaster. The program itself was supported by the Ford, Gates, MacArthur, Rockefeller, and Russell Sage Foundations, and sponsored by the Social Science Research Council. This is the most comprehensive social science coverage of a disaster to be found anywhere in the literature. It is also a deeply human story being told here.

Recommended Resources

Adams, Vincanne, Taslim van Hattum and Diana English. "Chronic Disaster Syndrome: Displacement, Disaster Capitalism, and the Eviction of the Poor from New Orleans." American Ethnologist 36, no. 4 (November 2009): 615–636.

Angel, Ronald J., Holly Bell, Julie Beausoleil, Laura Lein. Community Lost: The State, Civil Society, and Displaced Survivors of Hurricane Katrina. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Masquelier, Adeline. "Why Katrina's Victims Aren't Refugees: Musings on a 'Dirty' Word." American Anthropologist 108, no. 4 (December 2006): 735–743.

Walser, Jim. "Government in South Carolina: Taking Care of Business." Southern Changes 6, no. 3 (1984). http://beck.library.emory.edu/southernchanges/article.php?id=sc06-3_003.

Weber, Lynn and Lori Peek, ed. Displaced: Life in the Katrina Diaspora.Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012.

Links

Latino Populations in South Carolina, 1990–2002

http://www.sph.sc.edu/cli/documents/vandermey%20working%20paper.pdf.

Map of Katrina's Diaspora

http://www.nytimes.com/imagepages/2006/08/23/us/24katrina_graphic.html.

Migration Patterns and Mover Characteristics from the 2005 ACS Gulf Coast Area Special Products

http://www.census.gov/newsroom/emergencies/additional/gulf_migration.html.

Similar Publications

| 1. | V. O. Key, Jr., Southern Politics in State and Nation (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1949); Joel Williamson, The Crucible of Race: Black and White Race Relations in the American South (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984); Michael Goldfield, The Color of Politics: Race and the Mainsprings of American Politics (New York: New Press, 1997); Jeffrey S. Lowe and Todd C. Shaw, "After Katrina: Racial Regimes and Human Development Barriers in the Gulf Coast Region," American Quarterly 61, no.3 (September 2009): 803-827. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Lowe and Shaw; Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2007). |

| 3. | Lowe and Shaw; Klein; Lynn Weber, "Intersectionality, Gender, and Health: What Katrina Reveals," (paper presented at Social Science & Medicine, Gender & Health Special Issue Workshop: Relational, Biosocial, and Intersectional Approaches, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, 2010); Mark M. Smith, Camille, 1969: Histories of a Hurricane (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011). |

| 4. | Central Midlands Council of Governments, Region Report: West Metro Area, 3, no. 1 (Spring 2006), http://www.centralmidlands.org/pdf/caycewcola06.pdf (accessed February 17, 2011). |

| 5. | Center for Research on Women, Across Races & Nations: Building New Communities in the US South (Memphis, TN: University of Memphis, 2006); State of South Carolina Commission for Minority Affairs, "South Carolina Hispanic/Latino Report" (Columbia: South Carolina Commission on Minority Affairs, 2006), http://www.state.sc.us/cma/data/FINDINGS%20REPORT2006.pdf (accessed February 21, 2011); Heather A. Smith and Owen J. Furuseth, Latinos in the New South: Transformations of Place (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2006). |

| 6. | Brenda Vander Mey and Ashley W. Harris, "Latino Populations in South Carolina, 1990-2002," working paper (Clemson, SC: Department of Sociology, Clemson University, 2004). |

| 7. | For a variety of reasons, the Hispanic population is undercounted by census enumerators. The most common factors associated with undercount of Hispanics in the census include complex household makeup or cultural differences in defining households, individual/family mobility, legal (authorized versus unauthorized) status, fear or distrust of government, and language barriers. See Elaine Lacy, "Mexican Immigrants in South Carolina: A Profile" (Columbia: University of South Carolina, 2007). |

| 8. | Bret Kloos, Kater Flory, Benjamin L. Hankin, Catherine A. Cheely, and Michelle Segal, "Investigating the Roles of Neighborhood Environments and Housing-based Social Support in the Relocation of Persons Made Homeless by Hurricane Katrina," Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community 37, no. 2 (2009): 143-154. |

| 9. | Ibid. |

| 10. | Trained graduate-student research assistants and I conducted the interviews, and participants provided informed consent beforehand. All interviews were audiotaped, professionally transcribed, and coded for analysis. Details of the study's methodology are published in Lynn Weber, "When Demand Exceeds Supply," Displaced: Life in the Katrina Diaspora (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012), 84-86. |

| 11. | Laura R. Woliver, "Abortion Conflicts, City Governments and Culture Wars: Continually Negotiating Coexistence in South Carolina," in Culture Wars and Local Politics, ed. E. Sharpe (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1999), pp. 21-42; Laura R. Woliver, The Political Geographies of Pregnancy (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002). |

| 12. | Richard Fausset, "South Carolina's Governor May Turn Down Stimulus Money," Los Angeles Times, February 21,2009; Editorial, "Courting Disaster in South Carolina," New York Times, March 30, 2009. |

| 13. | Sheila Crowley, "Where Is Home? Housing for Low-Income People after the 2005 Hurricanes," in There Is No Such Thing as a Natural Disaster: Race, Class, and Hurricane Katrina, ed. C. Hartman and G. D. Squires (New York: Routledge, 2006), pp.121-166. |

| 14. | Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Housing Vouchers Funded in South Carolina under Pending Proposals, November 1, 2006, http://www.cbpp.org/files/11-1-06hous-sc.pdf (accessed February 17,2011). |

| 15. | John O'Connor, "West Columbia Accused of Blocking Apartments," The State, February 18, 2005; Tim Flach, "West Columbia Paying Out $600.000," The State, March 4, 2008; Tim Flach, "Builders Urge More Attention to Low-Income Homes," The State, March 13, 2008. |

| 16. | Child Welfare Leagues of America, "South Carolina's Children 2008," http:// www.cwla.org/advocacy/statefactsheets/2008/southcarolina.htm (accessed February 17, 2011). |

| 17. | South Carolina Department of Commerce, "High-Growth Jobs in South Carolina: Labor Market Information," July 2008, http://www.workforcesouthcarolina.com/media/3163/highgrowthjobs072008.pdf (accessed February 21, 2011). |

| 18. | United Way of the Midlands, Facing Facts: United Way of the Midlands Update for 2004: A Study of Issues That Shape Our Region (Columbia, SC: United Way of the Midlands, 2004). |

| 19. | Shalama Jackson, "Lexington County—Public Transportation Dilemma—Bus Service Cuts Thwart Disabled," The State, February 2, 2007; Shalama Jackson, "Funding the Transit System: Low Ridership Might End Services-Lexington County," The State, June 5, 2007. |

| 20. | Ibid. |

| 21. | David C. Ribar, Marilyn Edelhoch, and Qiduan Liu, South Carolina Food Stamp and Well-Being Study: Transitions in Food Stamp and TANF Participation and Employment among Families with Children (United States Department of Agriculture, April 2006), http://hdl.handle.net/10113/32788 (accessed February 16, 2011). |

| 22. | Ibid. |

| 23. | Child Welfare Leagues of America, "South Carolina's Children 2008," http:// www.cwla.org/advocacy/statefactsheets/2008/southcarolina.htm (accessed February 17, 2011). |

| 24. | Jenny Burns, "No Pressure: Bible Belt Families Welcome Muslim Refugees,"The State, March 12, 2004; Joy Woodson, "Open Arms Missing to Greet Refugees: Sponsors Lacking as Charities Welcome Persecuted People to New Lives in Columbia," The State, August 24, 2006; Joy Woodson, "Yesterday's Refugee, Tomorrow's Architect," The State, April 20, 2007. |

| 25. | "Federal Agency Calls Off Bantu Resettlement in Cayce," The State, October 9, 2003; "US City Refuses to Admit Somali Bantu Refugees," The State, October 13, 2003. |

| 26. | Adam Beam, "Group Plans 15 Million Dollar Homeless Center," The State, June 26, 2008; Adam Beam, "Neighbors to Fight Homeless Shelter," The State, October 5, 2008. |