Overview

In 1859, one of the largest sales of enslaved people in US history took place at the Ten Broeck Race Course, now an obscured landscape, on the outskirts of Savannah, Georgia. Four hundred and twenty-nine enslaved persons from the Butler plantations near Darien were sold in an event remembered as "The Weeping Time." Despite the prevalence of historic monuments in the US South, memorials to slavery are rare or recent arrivals. Not until 2008 did the city of Savannah and the Georgia Historical Society place a marker near the site of the sale. In this essay, Kwesi DeGraft-Hanson examines how this once hidden landscape can be re-imagined into Savannah's historic memory through archival research, oral history, physical observations of the landscape, and the art of mapmaking.

Introduction

The blades of grass on all the Butler estates are outnumbered by the tears that are poured out in agony at the wreck that has been wrought in happy homes, and the crushing grief that has been laid on loving hearts.

—Mortimer Thomson (Philander Doesticks)1Q. K. Philander Doesticks, "Great Auction Sale of Slaves at Savannah, Georgia, March 2d and 3d, 1859," The New-York Tribune, March 9, 1859, 8.

Fitzhugh Brundage has noted that the contemporary term used to describe how people remember and articulate their history is "historical memory," an imprecise recollection not of "fixed images of the past that [they] retrieve intact through acts of memory," but "memory as an active, ongoing process of ordering the past," a "product of intentional creation."2W. Fitzhugh Brundage, The Southern Past: A Clash of Race and Memory (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005), 4. Historical memory is a dynamic, active, ordering of the past. We remember selectively and parochially.

In The Southern Past, Brundage examines black and white southern historical memory. Immediately after the Civil War, southern whites assuaged their defeat by claiming and dominating not only public spaces with monuments to the Confederacy, but utilized history departments and college faculty to inscribe their version of a paternalistic, elite culture of their colonial and antebellum past. Brundage contrasts this white spatial aggression with black remembrances and their methods of enshrining their version of historical memory. Black teachers and schools—as well as public parades like Juneteenth and Emancipation Day celebrations—allowed blacks to, if even temporarily, lay claim to civic spaces typically already appropriated by whites.

|

| Detail of Pierce Mease and Frances Kemble Butler from a daguerreotype. |

Many US landscapes occupied and used during the era of enslavement remain unmemorialized, carrying no sign or evidence that these places were as significant to the geography of enslavement as European ports such as Lisbon, Liverpool, Nantes, and Copenhagen, where ships were outfitted for the trade. Or as significant as the forts, castles, and settlements in the African interior or along the coast that were points of origin or holding areas.3Kwesi DeGraft-Hanson, "The Cultural Landscape of Slavery at Kormantsin, Ghana." Landscape Research 30, no. 4 (October 2005): 461. Or as important to the Atlantic slave economy as were destination coasts, warehouses, slave marts and plantations in the Americas—plantations such as those of the Butler family, among the most productive in the US South. Pierce Butler (1744–1822), the original proprietor, was an associate of Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, Aaron Burr, and Alexander Hamilton, and a signer of the US Constitution.

In 1859, one of the largest sales of enslaved people in US history took place at the Ten Broeck Race Course, now an obscured landscape, on the outskirts of Savannah, Georgia. At the behest of Pierce Mease Butler (1810–1867), 429 enslaved persons from the Butler plantations near Darien were sold in an event known and remembered as "The Weeping Time."

Because of the size of this sale, its effects upon those who were sold and their descendants, and the extent to which it inflamed the tensions leading to the Civil War, the Ten Broeck Race Course is an important cultural landscape and a place of heartbreak.4Keith H. Basso, Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language among the Western Apache (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996). Yet it was not until 2008 that the city of Savannah and the Georgia Historical Society placed a marker near the site of the sale.5The precise sale site is a quarter mile away, and not visible, from the commemorative marker. The significance of the Weeping Time sale and how the Ten Broeck Race Course came to be marked is the subject of this essay.

Landscapes are dynamic, challenging to envision when few vestiges remain. They have to be "read" in different ways, using various methods to decipher their past.6Richard Muir, Approaches to Landscape (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1999). Landscape is an "accumulation," an accrual of the social and material changes of its inhabitants as well as geographical changes and accretions.7D. W. Meinig, ed., The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes: Geographical Essays (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), 7. In spite of the mutability of landscape, it is often possible to unearth and retrieve hidden histories. Augmenting archival research with oral history, physical observations of the landscape, and the work of numerous scholars, reimagining the Ten Broeck site brings commemorative attention to those who were sold there.

The Weeping Time

On the second and third days of March 1859, absentee Georgia planter Pierce Mease Butler of Philadelphia had arranged for the sale of 429 enslaved in Savannah to pay off enormous gambling debts, recoup stock market losses, and stay solvent.8Butler resided mainly in Philadelphia, but spent a few months out of some years visiting his Georgia plantations inherited from his maternal grandfather, Major Pierce Butler. The major's will stipulated that for his grandson(s) to inherit his properties they had to change their last name from Mease, to Butler. For brief biographic details of both Mease Butler and Major Butler, see The New Georgia Encyclopedia (http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-617); for complete biographic information about the Butler family, see Malcolm Bell, Jr., Major Butler's Legacy: Five Generations of a Slaveholding Family (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1987). Because Butler visited the plantations infrequently, he depended on overseers like Roswell King, Sr., and his son Roswell, Jr., for daily management. Between them, the two Kings managed the Butler plantations in succession, from 1803 through the 1840s, serving three generations of Butlers. The people to be sold constituted almost half of the total 919 bondsmen and women held on two coastal Georgia plantations Butler owned with Gabriella, his brother John's widow. This disastrous, ill-fated sale was known as "The Weeping Time," an apt expression of the angst and anguish that this sale caused the enslaved who were separated from their loved ones.9Bell, Major Butler's Legacy, 339. See also, Africans in America, a 1998 PBS documentary, online at www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia.

Pierce Butler had the impending sale advertised continuously in The Savannah Republican, The Savannah Daily Morning News, and in contemporary newspapers throughout the southeastern states by Joseph Bryan (1812–1863), Savannah's largest and most notorious slave-dealer. According to historian Malcolm Bell, Bryan "had a virtual monopoly of the coastal Georgia slave trade."10Bell, Major Butler's Legacy, 511. The advertisement that Bryan published in The Savannah Republican began on February 8 and ran daily, except on Sundays, through March 3, the last date of the slave sale.

|

| A detail from Joseph Bryan's initial advertisement for the Butler "Sale of Slaves," The Savannah Republican, Tuesday, February 8, 1859. |

His advertisement in The Savannah Republican on February 8, 1859 reads:

FOR SALE. LONG COTTON AND RICE NEGROES.

A Gang of 460 Negroes, accustomed to the culture of Rice and Provisions; among whom are a number of good mechanics, and house servants. Will be sold on the 2d and 3d of March next, at Savannah, by JOSEPH BRYAN. Terms of Sale—One-third cash; remainder by bond, bearing interest from day of sale, payable in two equal annual instalments, to be secured by mortgage on the negroes, and approved personal security, or for approved city acceptance on Savannah or Charleston. Purchasers paying for papers. The Negroes will be sold in families, and can be seen on the premises of JOSEPH BRYAN, In Savannah, three days prior to the day of sale, when catalogues will be furnished. *** The Charleston Courier, (daily and tri-weekly;) Christian Index, Macon, Ga; Albany Patriot, Augusta Constitutionalist, Mobile Register, New Orleans Picayune, Memphis Appeal, Vicksburg Southern, and Richmond Whig, will publish till day of sale and send bills to this office.

"The premises of JOSEPH BRYAN" referred to Bryan's holding and trading pen on Savannah's Johnson Square. Inspection of the enslaved would have begun on February 26, the very day Bryan introduced another, modified ad about the impending slave sale in both The Savannah Republican and The Savannah Daily Morning News. Bryan changed the venue to the "Race Course," and reduced the number of persons for sale:

Mortimer Thomson (1831–1875), a reporter for the New-York Tribune, travelled to Savannah and infiltrated the buyers, pretending to be interested in purchasing enslaved people. During the sale, Thomson made "cautious bids" to prevent being discovered.11Ibid., 332. He wrote "Great Auction Sale of Slaves at Savannah, Georgia, March 2d and 3d, 1859," published in The New-York Tribune, on March 9 under his pseudonym, Q. K. Philander Doesticks. He described the expectant atmosphere in Savannah:

For several days before the sale every hotel in Savannah was crowded with negro speculators from North and South Carolina, Virginia, Georgia, Alabama, and Louisiana, who had been attracted hither by the prospects of making good bargains. Nothing was heard for days, in the bar-rooms and public rooms, but talk of the great sale . . .12Doesticks, "Great Auction," 4.

According to Doesticks, the race course where the "Great Auction Sale of Slaves" took place was situated "about three miles from the city, in a pleasant spot, nearly surrounded by woods." The site adjoined the Central of Georgia railroad.13Doesticks, "Great Auction," 12–13; Bell, Major Butler's Legacy, 329; Daina Ramey Berry, "'We'm Fus' Rate Bargain'; Value, Labor and Price in a Georgia Slave Community," The Chattel Principle: Internal Slave Trades in the Americas, ed. Walter Johnson, (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004), 65.

The enslaved were brought up from the Butler rice plantation, a 1,500-acre island in the Altamaha River estuary adjacent to Darien, Georgia, and from Butler's nearby cotton plantation, Hampton, on the north end of Saint Simons Island. They arrived in groups, by steamer and rail, several days before the sale and were sent to the Ten Broeck Race Course, where they were "quartered in the sheds erected for the accommodation of the horses and carriages of gentlemen [who attended] races."14Doesticks, "Great Auction," 9. Also, Bell, Major Butler's Legacy, 329.

After four days of prodding and inspection by prospective buyers, the enslaved suffered through the two-day sale. Some stood stoically, resignedly, attempting to keep their dignity, while buyers poked, pinched, and fondled them, looked into their mouths, insisted they bend over or extend their limbs, and searched for 'ruptures' or 'defects' that might affect their future productivity.15Doesticks, "Great Auction," 5, 19. Doesticks described the buyers as "generally of a rough breed, slangy, profane and bearish," including some "fast young men," "rough backwood rowdies" and also "[w]hite neck-clothed, gold-spectacled, and silver-haired old men." Pretend-buyer Doesticks recorded the facts of the sale, and his observations of the emotional impact on the men, women, and children (including thirty babies), who were sold for a sum of $303,850.16Ibid., 21, 27, 28.

Parents were separated from children, and betrothed from each other. Among the many wrenching stories Doesticks describes is that of a young, enslaved man, Jeffrey, twenty-three years old, who pleaded with his purchaser to also buy Dorcas, his beloved:

I loves Dorcas, young mas'r; I loves her well an' true; she says she loves me, and I know she does; de good Lord knows I loves her better than I loves any on in de wide world—never can love another woman half so well. Please buy Dorcas, mas'r. We're be good sarvants to you long as we live. We're be married right soon, young mas'r, and de chillum will be healthy and strong, mas'r and dey'll be good sarvants, too. Please buy Dorcas, young mas'r. We loves each other a heap—do, really, true, mas'r."17Ibid., 22, 23.

Realizing that his love alone would not impress his new "mas'r," Jeffrey tried to appeal to his purchaser's business sense by "marketing" his own prospective bride, in a desperate hope that they might be together:

Young mas'r, Dorcas prime woman—A1 woman, sa. Tall gal, sir; long arms, strong, healthy, and can do a heap of work in a day. She is one of de best rice hands on de whole plantation; worth $1,200 easy, mas'r and fus rate bargain at that."18Ibid., 22–23.

What is evident is the humanity of Jeffrey, Dorcas, and all the others seemingly commoditized by this sale. Jeffrey makes clear his love for Dorcas, and his plans for a future with her—a family that would include children, if even they would all be enslaved. Given the uncertainty of slavery, with its immanence of impending loss and unpredictable futures, Jeffrey felt that his best odds were to help broker his sweetheart's sale, and to suggest her market value.19On how the system of slavery often "check-mated" the enslaved, forcing them to make desperate choices, see Toni Morrison, Beloved (New York: Plume, 1987). In Beloved, Sethe slits her own young daughter's throat, killing her to prevent her being returned to the plantation from which she and her children had escaped. Morrison based her character on the true story of Margaret Garner (1834–1858). For an account of the Garner story, see: Steven Weisenburger, "A Historical Margaret Garner," accessed November 1, 2022, http://mullinspld.weebly.com/uploads/1/9/7/9/19799485/mgarner_history.pdf.

Jeffrey's new owner considered purchasing Dorcas until he realized that she was to be sold in a family of four, and could not be purchased independently. When Jeffrey's entreaties came to nothing and Dorcas was bought by someone else, he walked away and grieved, consoled in silence by a circle of his enslaved friends.20Doesticks, "Great Auction," 24, 25. Jeffrey and Dorcas were separated, ironically, because Pierce Butler had required that, to the extent possible, the enslaved be sold in "families."

In "'We'm Fus' Rate Bargain': Value, Labor, and Price in a Georgia Slave Community," Daina Ramey Berry explains that "Because [Jeffrey and Dorcas] were not married, there was no chance that they would be sold as a family." She points to the desperation that leads Jeffrey to suggest a purchase price for his beloved. While planters and agents were purchasing slaves "based on economic interest," the enslaved approached the auction block "with overt manipulation and covert strategies to maintain family ties . . . to try to keep relatives and loved ones together."21Berry, "'We'm Fus' Rate Bargain'", 67, 68.

Doesticks also tells of Daphne, a young woman who was wrapped in a shawl when ordered to mount the auction block. Buyers, bothered that they were thwarted from making "a thorough examination of her limbs," insisted that Daphne expose herself to their full scrutiny, one asking, "Who is going to bid on that nigger, if you keep her covered up? Let's see her face." Mr. Walsh, the auctioneer, spoke to the 200 buyers gathered at the platform and let it be known that Daphne had "been confined only fifteen days [earlier]," and that he felt "on that account she was entitled to the slight indulgence of a blanket, to keep from herself and child the chill air and the driving rain."22Doesticks, "Great Auction," 14, 21. A week after Daphne had given birth she, her husband, and their other small child, along with other enslaved, were sent up to Savannah from the Butler plantations. The family sold for $2,500.23Berry, "'We'm Fus' Rate Bargain'", 66.

In revealing emotions experienced by the enslaved, Doesticks paid particular attention to facial expressions and body language:

On the faces of all was an expression of heavy grief; some appeared to be resigned to the hard stroke of Fortune that had torn them from their homes, and were sadly trying to make the best of it; some sat brooding moodily over their sorrows, their chins resting on their hands, their eyes staring vacantly, and their bodies rocking to and fro, with a restless motion that was never stilled; few wept, the place was too public and the drivers too near, though some occasionally turned aside to give way to a few quiet tears.24Doesticks, "Great Auction," 10.

Resignation mixed with dignity and pain to tide the enslaved over during this wrenching transition from one place, and one bondage, to another:

The expression on the faces of all who stepped on the block was always the same, and told of more anguish than it is in the power of words to express. Blighted homes, crushed hopes and broken hearts was the sad story to be read in all the anxious faces. Some of them regarded the sale with perfect indifference, never making a motion save to turn from one side to the other at the word of the dapper Mr. Bryan, that all the crowd might have a fair view of their proportions, and then, when the sale was accomplished, stepped down from the block without caring to cast even a look at the buyer, who now held all their happiness in his hands.25Ibid., 19.

The "Weeping Time" brought much anguish to the enslaved. Families, who had been together for all of their lives on Butler's Island or Hampton, were torn apart and dispersed; many of them never saw each other again. The Butler enslaved were dispersed all over the southern states. The heavens seemed to weep in empathy as the four dry days during which buyers inspected the enslaved gave way to a brooding storm; it rained "violently," and the "wind howled" for the two days of sale, letting up only after the last person had been sold.26Bell, Major Butler's Legacy; Doesticks, "Great Auction," 13. Outside the advertisements, the Savannah newspapers offered cursory mention that the sale had taken place as planned. Slavery and slave sales were a way of life and livelihood in Savannah, and much of the US South. After Mortimer Thomson's Tribune article was published in the North, Savannah Morning News editor, William T. Thompson (1812–1882) castigated Doesticks as a spy, intimating that next time he came South, he would not get away.27Bell, Major Butler's Legacy, 312.

Detailing the callousness and heartlessness of slavery, Doesticks' published exposé was a political blow to the South, at a time of escalating sectional animosity. Like the arrival of the vessel Wanderer—which in November 1858 landed on Jekyll Island near Savannah—the last shipment of African captives brought to Georgia—the Ten Broeck sale exacerbated tensions between northern and southern states.28For the story and controversy surrounding the Wanderer, see Tom Henderson Wells, The Slave Ship Wanderer (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1967); also, Erik Calonius, The Wanderer: The Last American Slave Ship And The Conspiracy That Set Its Sails (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2006). See also Henry R. Jackson, The Wanderer case; the speech of Hon. Henry R. Jackson of Savannah, Ga., (Atlanta: E. Holland, 1891). The last documented shipment of enslaved Africans brought to the United States was disembarked at Mobile, Alabama in 1859 from aboard the schooner Clotilde, http://www.archives.gov/southeast/exhibit/popups.php?p=2.5.2, accessed September 12, 2008.

After the Civil War, some of the Butler enslaved returned to the plantations where they had been born or raised, where they felt most connected, in search of friends and families. Descendants of the Butler enslaved still live in Darien, Brunswick, St. Simons Island, and vicinity. Other Butler descendants can be found in Savannah, Charleston, Memphis and New Orleans, where the Butler slave sale was advertised, and in smaller nearby towns. Narratives of the "Weeping Time" have persisted among some African Americans of the Georgia Low Country.29Mills B. Lane, Neither More Nor Less Than Men: Slavery in Georgia: A Documentary History (Savannah: Beehive Press Library of Georgia, 1993). The efforts of Monifa Johnson, a contemporary resident of Savannah who was aware of this history, led to her city's commemorating the site.

Sale by Sale

The sales that took place throughout the antebellum southern states were horrific experiences for the enslaved. They were boisterous, raucous affairs involving buyers, brokers, and enslaved people. Walter Johnson's study of slave markets, focused on New Orleans (location of the largest US markets in the first half of the nineteenth century), shows how sales involved the traders' machinations and deceptions, the buyers' perceptions and intentions, and the enslaved person's efforts to influence who purchased them.30Johnson, Soul by Soul, 2, 117–134. Johnson argues that enslaved people were neither passive nor ever fully commoditized; rather, that they were keenly aware of what persons and qualities slaveholders were seeking and used that knowledge to their advantage; feigning ill-health or lack of energy to disinterest buyers they perceived to be harsh masters; appealing to other buyers to purchase them and their loved ones.31Ibid, 164, 165, 179, 214.

Ultimately the majority of enslaved persons were sold to whomever selected them. "In the slave market," writes Johnson, "slaveholders and slaves were fused into an unstable mutuality which made it hard to tell where one's history ended and the other's began. Every slave had a price, and slave communities, their families, and their own bodies were suffused with the threat of sale, whether they were in the pens or not. And every slaveholder lived through the stolen body of a slave."32Ibid, 214. What sets the sale at Ten Broeck apart from the countless other sales of enslaved persons in the antebellum South is its magnitude. The anguish and separations were multiplied for the enslaved; more families, more couples, more children were violated.33See Doesticks. Bell captures the emotions and frustrations of the enslaved in the chapter: "The Weeping Time." See also Berry, "'We'm Fus' Rate Bargain'", 64, for a discussion on the slaves' perspectives, and the social impact of this slave sale.

If Pierce Mease Butler and the sale of enslaved people he ordered hastened the advent of the Civil War, his former wife, Frances Anne (Fanny) Kemble (1809–1893), may have influenced the war's outcome. Four years after Ten Broeck, and at the height of the Civil War, Kemble published a journal she had written fifteen years earlier, when she and Butler resided for three months at Butler Island and Hampton plantations. Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838–1839, published in London and New York in 1863, was a blistering exposé of plantation slavery and mentioned many of the enslaved sold in 1859. Kemble had advocated for the general welfare of the enslaved while she lived on the Butler plantations. Her Journal, among other provocations, prompted Mortimer Thomson's (Doesticks's) account to be reprinted in 1863 as: What Became Of The Slaves On A Georgia Plantation? Great Auction Sale Of Slaves At Savannah, Georgia, March 2d & 3rd, 1859. A Sequel to Mrs. Kemble's Journal. It is unclear who published it, likely the New-York Tribune. In what one writer has called "a sensation little short of that which followed the appearance of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin," Kemble's Journal affected British sentiment, perhaps turning away some financial and military assistance from the Confederacy.34For a synopsis of both sides of this controversy, see the Editors' Introduction pages by John A. Scott, in Frances A. Kemble, Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838–1839, ed. and introduction John A. Scott (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1961), l-lii.

Hidden Landscapes of Slavery

The natural and human landscape of the Georgia and Carolina coasts was drastically changed after the Civil War, a result of military devastation, the collapse and reorganization of agricultural production, and the slow and uneven emergence of capitalist modernization. "By the end of the nineteenth century," writes environmental historian Mart Stewart, "the old plantation agricultural landscape had been replaced by a patchwork of small farms and open land, port towns and market gardens, and sea island hunting reserves and vacation retreats."35Mart A. Stewart, "What Nature Suffers to Groe": Life, Labor and Landscape on the Georgia Coast, 1780–1920 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1996): 194. And see Charles S. Aiken, The Cotton Plantation South since the Civil War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998). Yet, even now, on surviving "plantations," the big house may be extant, but few structures directly related to the enslaved—dwellings, barns, and mills—remain.36See Michael Vlach, Back of the Big House; The Architecture of Plantation Slavery (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1993). Replaced, reordered, and erased sites of habitation and work constitute hidden and obscured landscapes of enslavement.

Concomitant with hidden landscapes of enslavement are the similarly obscured personal histories or narratives of the long-ago enslaved. These narratives are often couched in the landscape as cultural, material fragments and as oral histories. Crucial to understanding the regional and national cultural histories, the retrieval process requires interrogating hidden landscapes as archives.

Theodore Rosengarten has noted that at Middleton Plantation on the Ashley River near Charleston, South Carolina, there are no extant records or signs to indicate where dwellings of enslaved people existed.37John Beardsley, Art and Landscape in Charleston and the Low Country: A Project of Spoleto Festival USA, with contributions by Roberta Kefalos and Theodore Rosengarten; principal photography by Len Jenshel. (Washington, DC: Spacemaker Press, 1998), 30. At Butler Island in the Altamaha estuary of coastal Georgia, which at its peak held over 500 enslaved people, no visible markers provide evidence of dwellings or of a slave hospital that existed on a plantation site inhabited from 1793 until well after the Civil War.38Theresa Singleton has stated that by the 1880s, Butler Island was no longer inhabited. See her The Archaeology of Afro-American Slavery in Coastal Georgia: A Regional Perception of Slave Household and Community Patterns (PhD diss., University of Florida, 1980), 56. The interpretation of such landscapes can begin with archival records and progress to the physical landscapes. Lists in planter family papers reveal personal information about the enslavers and the enslaved. Plantation rice landscapes disclose irrigation channels, levees separating fields from adjacent rivers, and the gridded network of canals and fields, including the characteristic "trunks" that allowed water on and off.39See Sam B. Hilliard, "The Tidewater Rice Plantation: An Ingenious Adaptation to Nature," in Coastal Resources, Geoscience and Man, 12, ed. H.J. Walker. (Baton Rouge: The School of Geoscience, Louisiana State University, 1975): 62. Pierce F. Lewis, "Axioms for Reading the Landscape" in The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes: Geographical Essays, 12. For a comprehensive work on reading the landscape, see Richard Muir, Approaches to Landscape (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1999) and The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes. See William G. Thomas III, "The Countryside Transformed." Landscapes are written on, erased, and re-inscribed by succeeding cultures. Architecture, agriculture, war, pillage, famine, and pollution are cultural inscriptions archived in the land, over time.

The palimpsestic nature of landscapes—their ability to be inscribed, erased and re-inscribed—allows them to be read for their secrets.40Lewis, "Axioms for Reading the Landscape," 12. Plantation slavery produced significant changes along the Carolina and Georgia coasts. Enslaved laborers cleared swamps thick with cypress groves and matted vegetation, creating rice plantations replete with dikes to regulate water-flows from adjacent rivers via irrigation canals. Enslaved people also cleared wooded landscapes for cotton production. Following the post-Reconstruction era, new activities of agriculture, industry, and urbanization altered the plantation landscapes. Envisioning earlier landscapes is an act of changing and remaking, accompanied by biases, preferred visions (literally and figuratively), environmental knowledge, and conceptual frameworks.41Stewart, "What Nature Suffers to Groe": Life, Labor and Landscape on the Georgia Coast, 1780-1920, 12.

Like landscape, the institution of slavery was subject to dynamic change. William Dusinberre's Them Dark Days: Slavery in the American Rice Swamps, a grim recounting of the plantation system, depicts the extreme changes in the labor force and lives of enslaved people. Dusinberre examines a handful of plantations, including Butler Island. His work substantiates Kemble's, narrating the brutality and degradation of both rice and cotton plantations.

Dusinberre shows how enslavement was always in dynamic flux. Plantation ownership changed, as did the labor force, as well as overseers with their particular management regimens of combating the vagaries of tide and weather. The "miasmic" rice plantations had "frightful" infant mortality rates: over half of all enslaved children born at Butler Island perished before their sixth birthday; sixty percent died before age sixteen. Dusinberre recounts the labor and sexual demands imposed on enslaved women whose health was "shattered by the field work required of them until soon before, and again soon after, their frequent pregnancies."42Dusinberre, Them Dark Days, 235, 237, 239.

With the high infant and child mortality rates, the summer malarial fevers, the deaths from drowning and venomous snake or alligator attacks, and deaths from severe floggings and punishments meted out most rice fields, like Butler Island plantation, were killing fields; so much so, that some rice planters had to import slaves from their interior cotton plantations in order to maintain their Lowcountry labor requirements.43Mart A. Stewart, personal communication, August 2009. A motion picture film that dealt with the Vietnam/Cambodia war popularized the term "killing fields."

In his environmental history "What Nature Suffers to Groe": Life, Labor and Landscape on the Georgia Coast, 1780–1920, Mart Stewart describes the dynamism of many plantations, including the Butler family's. In the plantation South, writes Stewart, man attempted to dominate or control nature, and he succeeded only temporarily and only by harnessing and coercing slave labor. Following the Civil War, the planters' ability to coerce labor and attempt to dominate nature was lost. Nature's rivers, floods, freshets and hurricanes countered efforts to subdue land and tides to narrow agricultural purposes. Stewart argues that the plantations that were created were a result of socially dynamic forces, and that the enslaved created counter-landscapes in their own spaces—different in scale and order from the sites worked under coercion.44Stewart, "What Nature Suffers to Groe".

The work of environmental historian Linda Nash complements Stewart. While nature does not have "agency," in that it does not have "intentionality," Nash concludes that human agency is influenced and shaped by nature and environment—"that so-called human agency cannot be separated from the environment in which that agency emerges."45Linda Nash, "The Agency of Nature or the Nature of Agency?" Environmental History 10, no. 1 (2005): 69.

"For those who found themselves in this location, both slaves and planters," writes Nash, "the characteristics of the Georgia landscape suggested certain alternatives. To put it simply, tidewater rice cultivation could be imagined on the Georgia coast but not in the Colorado desert . . . What we might label planters' (or slaves') "intentions" were always under adjustment.46Ibid, 69. In other words, it was not merely the particular techniques of rice cultivation but the very ability to envision those techniques that emerged when planters and enslaved interacted with the tidewater lowlands.

Initially part of the "Indian Lands" when General Oglethorpe and his cohort arrived in the Savannah area in 1733, the future site of Ten Broeck Race Course became part of a plantation, Vale Royal, owned by a succession of owners. Known as "Oglethorpe's race track," it was definitely used for riding in the late 1790s. By the late 1850s, it was a refurbished horse-racing track under the leadership of Charles Lamar, proprietor of the ship, the Wanderer, and the president of the Savannah Jockey Club. The Ten Broeck sale of enslaved persons is the major event shaping the memory of this place, a "stream braided from the old and new," from plantation landscape and horse racing track. Now, in the ongoing mutability of landscape, it is part industrial site with a plywood manufacturing company, part elementary school site, and is bisected by a highway.47The statement that there was a riding track at the site of the Ten Broeck race course in the 1790s is from Keber, "Sale of Pierce M. Butler's Slaves; March 2–3, 1859. Ten Broeck Race Course," Georgia Historical Society, Unpublished paper, 2007, 2; Stewart, "What Nature Suffers to Groe."

Where I Enter

Growing up in Ghana (the former Gold Coast), West Africa, in the coastal towns of Accra and Cape-Coast, I was often within ten miles of one of the twenty-odd surviving forts and castles strung along the country's Atlantic littoral. At age fourteen I visited Cape Coast Castle, built by Swedes in 1653 and eventually taken over by the British in 1665. From the tour guide, I learned of the men and women who had been kidnapped, bought and sold, and shipped as captives from the castle. In the castle's dank dungeons, I could smell traces of the enslaved, trapped in time and space; the mixed odors of sweat and human excreta exist there today. Fifteen miles from Cape-Coast Castle is Elmina Castle, begun in 1481 by the Portuguese—the first European fortification on the West African coast. Although these two castles were major sites in the geography of Atlantic slavery, I was oblivious to much of this history while I lived in Ghana.48The dates given for Cape Coast castle are from: K. J. Anquandah, Castles and Forts of Ghana. (Paris: Atalante: Ghana Museums and Monuments Board, 1999).

I came to the United States for graduate studies in landscape architecture, and learned to appreciate designed spaces and the natural environments of the Georgia and South Carolina coasts. I am married to an African American from Savannah, and our first jobs out of college took us to Charleston. Travelling and working in the Low Country, I became interested in tabby, a colonial concrete made from equal proportions of oyster shells, water, lime (from burning oyster shells), and sand. Researching tabby led to an interest in plantations and the enslaved, when, in 1997, I recognized some distinctly Ghanaian (Gold Coast) names embedded in Malcolm Bell's Major Butler's Legacy: Five Generations of a Slaveholding Family. I recognized Akan (Gold Coast) names in a chapter about enslaved of the former Butler plantations. Though the orthography of some of the names was different from current Ghanaian names, the differences were slight, and actually served to recall names I was familiar with, and elicited in me a kinship with these former enslaved people. My knowledge of the harsh conditions that the enslaved endured, and the fact that their labors and contributions were not only unrequited but largely without memorialization led me to think about commemorations of hidden, erased and silent landscapes of slavery.

Searching for Ten Broeck

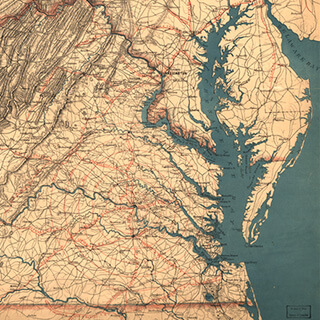

I was surprised that people I queried in Savannah knew nothing about the Ten Broeck sale. I searched archives for period maps of Savannah and Chatham County, examined written documents that might refer to the race course site or to events that took place there, and traveled in search of the site. I studied maps, images, histories and news articles of Savannah produced from 1734 through the present, but concentrated my focus on the period 1845 through 1875. Since at least three written sources indicated that the Ten Broeck Race Course was "three miles" west of Savannah on the Central of Georgia Railroad, my hope was to find maps that would show enough land area in enough detail to allow identification.49Doesticks, "Great Auction"; Bell, Major Butler's Legacy, 329; Fraser, Savannah in the Old South, 310.

My research yielded graphic and textual information and led me to people who knew about the site's history through research and oral history. Research at Emory University's Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Book Library (MARBL) and at the Georgia Historical Society (GHS) archives in Savannah yielded maps from the 1730s through the nineteenth century, documenting the site of the sale, including one that actually locates the Ten Broeck Race Course. At MARBL, I viewed maps of Savannah dating back to 1734, when the city was taking form. Georgia, a slave-free state at its inception, legalized slavery in the 1750s. Rice plantations flourished along the Savannah River. The city expanded its boundaries on all sides. With copies of maps in hand, I searched for the race course and the Central of Georgia Railroad, commissioned in the mid-1830s.50Thomas Gamble, "A History of the Municipal Government of Savannah from 1790 to 1901," in Report of Hon. Herman Myers, Mayor, Together With The Reports Of The City Officers Of The City Of Savannah, Ga., For The Year Ending December 31, 1900: To Which Are Added The Commercial Statistics Of The Port, Reports Of Public Institutions, Ordinances Passed During The Year 1900, And A History Of The Municipal Government Of Savannah from 1790 to 1901 (Savannah, 1901), 170–177. The Central of Georgia Company was organized in December 1833; however, exact dates for when portions of rail lines were constructed are sketchy. Gamble (1901) is an excellent, but tedious source. See also, Ron Wright, "History of the Central of Georgia Railway," Central of Georgia Railway Historical Society, http://cofg.org/index.php?option=com_content/&task=view&id=77&Itemid=43, accessed August 11, 2006.

In the 1818 plan of Savannah with the squares James Oglethorpe laid out, Johnson Square (where slave dealer Joseph Bryan would one day have his slave pen and office) is faintly discernible just south of the Savannah River and the "Exchange" (north is to the bottom of the page, and west is at the reader's right hand). To the west of 'West Broad Street,' and not too far from the Savannah River and 'Indian Street' on this map, is a label for 'Bryan Street,' named after an earlier (related) Joseph Bryan, "benevolent friend of [James] Oglethorpe, who came [from South Carolina] with four of his sawyers in 1733 and gave their labor free for two months."51Gamble, "A History of the Municipal Government of Savannah from 1790 to 1901," 38.

Bryan Street runs adjacent to Johnson Square. This map shows the west area of the city as agricultural lands. "Yamacraw" and "Indian St." allude directly to First Nations/Native American tenure on the land. Discussing Savannah's history, Thomas Gamble, writer, historian and Mayor of Savannah (1933–1937 and 1939–1945), writes that in 1766 "The city is increased by two suburbs; the one to the west is called Yamacraw, a name reserved from the Indian town formerly at this place, of which the famous Thamachaychee [Tomochichi] was the last king."52Ibid., 33.

Earlier eighteenth-century maps clearly indicated that these were "Indian lands." The area that was to become the Ten Broeck Race Course is not in the image, but is further to the west in the area shown (by dots) as vegetated. Fifty years later, Savannah's growth and prosperity is evident in J.B. Hogg's 1868 map, which shows the city's expanded boundaries in 1868. The racecourse location is not captured in this map. At the west side of the city (north is to the bottom of the page), the words: "CENTRAL RAILROAD DEPOT" are evident adjacent to the intersection of Liberty and West Broad Streets; and the rail tracks are visible heading west toward Macon, their immediate destination. The racecourse would be located an equal distance west from the edge of the image as the depot is to the east, situated along the Central of Georgia lines.

The racecourse was most likely named for Richard Ten Broeck (1812–1892), of Albany, New York, an avid horseman and racing promoter throughout the country.53For information on Richard Ten Broeck and his horse racing exploits, see John Dizikes, Sportsmen and Gamesmen (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981), 124–157; also John Dizikes, Yankee Doodle Dandy: The Life and Times of Tod Sloan (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), 104–106. An electronic search of historical newspapers, using the Ten Broeck name, unearthed an article in the Spirit of the Times, published in New York, January 17, 1857:

I knew that a Charles Augustus Lafayette Lamar (1824–1865), a former Savannah police chief and ardent secessionist, had been indicted in 1859 by the US government for importing enslaved Africans in the Wanderer case. The Africans that Lamar brought to nearby Jekyll Island, then to Savannah, were among the last shipments of enslaved Africans to North America, and definitely the last such shipment to Georgia. These Africans from the Congo area were brought aboard the Wanderer, a fast, sleek galley outfitted to accommodate the enslaved and to out-run naval ships patrolling the high seas. A Savannah jury acquitted Lamar of federal charges. I was surprised to find his name connected in 1857 with the Ten Broeck Race Course and site of the 1859 slave sale.

Landscape and Memory

In November 2007, at the Georgia Historical Society Archives in Savannah, I learned that a former Georgia College and State University history professor, Martha Keber, had preceded me in the search for the Ten Broeck Race Course. The city of Savannah commissioned her in September 2006 to document the history of the racecourse and sale site as part of the implementation of a comprehensive neighborhood redevelopment plan, the West Savannah Revitalization Plan (WSRP), and the city's decision to commemorate the slave sale.54Allynne Tosca Owens, City Planner, City of Savannah, personal communication, March 2, 2009. The city's actions were prompted by Monifa Johnson, a niece of Mayor Otis Johnson, who knew about the sale, and shared that knowledge with Allynne Tosca Owens, the WSRP project manager, when she realized that West Savannah was to undergo redevelopment. Owens, a city planner, thought the historical facts warranted a public research project, an idea supported by Mayor Johnson and city manager Michael Brown. Monifa Johnson recalls hearing about the slave sale from her grandfather who sometimes made statements like, "here is where Pierce Butler's slaves were kept." "There were always people on the west side of Savannah," Johnson says, "who knew about the slave sale." Growing up, she heard "tidbits here and there" that she later followed up.55Monifa Johnson, personal communication, March 2, 2009. In his book, Neither More Nor Less Than Men: Slavery in Georgia: A Documentary History (Savannah: Beehive Press Library of Georgia, 1993), Mills B. Lane prints Doesticks' account of the auction sale of slaves.

Keber and her husband Robert made an application on February 20, 2007, to the Georgia Historical Society (GHS) on behalf of Savannah for a historical marker to commemorate the 1859 sale of enslaved persons. The GHS presented the proposed marker to Savannah's Monument and Sites Committee, and subsequently to the full Savannah City Council on August 2, 2007. The proposed placement of the marker was at 2053 Augusta Avenue, a site acquired by Savannah for this purpose.56Allynne Tosca Owens, personal communication, November 2007; Owens, personal communication, July 10, 2008. See also the online archive of the Savannah City Council Meeting minutes, Aug. 2, 2007, http://www.ci.savannah.ga.us/Cityweb/minutes.nsf/80A034128361E60E85257337004B72AF/$file/08-02-2007.pdf, 10–14. Accessed, November 2007, and July 15, 2008.

In 2007, Keber produced an unpublished seven-page document, "Sale of Pierce M. Butler's Slaves; March 2–3, 1859. Ten Broeck Race Course," as the necessary historical background to accompany the marker request. Keber's paper mentions that horse racing on the site later called the Ten Broeck Race Course probably dates to the 1790s, when "gentlemen tested their best mounts on a sandy track," a mile in length, and a "rounded rectangle in shape."57Keber, "Sale of Pierce M. Butler's Slaves," 2. She writes that the 1872 Platen map, an amalgam of several earlier maps, "gives the clearest image" of the course, though "its precise location on Louisville Road is unclear." Keber annotated a recent, undated Savannah City map, and shows (by an oval) the general area of the race course location. Keber's map (north is to top of page) shows the Ten Broeck Race Course site bounded by the contemporary streets of Abbot St. (east), Louisville Rd. (south), railroad tracks parallel to Hopper St. (west) and Old Lathrop and Augusta Avenue to the north. At the Georgia Historical Society, she had also found 1890s photographs of some Savannah Jockey Club members at the Ten Broeck Race Course. These photographs (which I also reviewed) provided images of the course, grandstand, and other structures and corroborated Doesticks's article and The Spirit of the Times. I met and talked with Dr. Keber in February 2008 in Savannah about our mutual work on the race course and her published history of West Savannah.58Martha L. Keber, Low Land and the High Road: Life and Community in Hudson Hill, West Savannah, and Woodville Neighborhoods (Savannah: The City of Savannah's Department of Cultural Affairs, 2008).

Honing In

On the maps that I reviewed at MARBL and GHS, Louisville Road and Augusta Road were visible; Louisville Road runs adjacent and parallel to the Central of Georgia Railroad tracks. Using each map's scale, I measured three miles from the outer limits of Savannah along the Central of Georgia tracks. The triangular area bounded by Augusta and Louisville roads was almost always at the three-mile mark. Even prior to seeing the 1872 Platen map, I was convinced that the racetrack was in the immediate vicinity, but where was its exact location?

This excerpt from the Platen map shows a "Race Course" three miles west of Savannah, adjacent to the Central of Georgia. The Savannah River (and north) is to the bottom of the page. Louisville Road and the Central of Georgia tracks parallel each other as the dark central spine in the image (oriented south-west to north-east). Augusta Road is the diagonal that appends Louisville Road. That the race course is so clearly delimited is as exciting as the multiple cultural layers evident in the map. Former plantation names and attendant boundaries are inscribed, as are hydrologic features. Immediately adjacent to the Savannah River (bottom of image), the words 'Vale Royal,' 'Glebeland,' 'McAlpine,' 'Hermitage' and 'Retreat' are discernible; these were plantations.

The land that became the Ten Broeck Race Course was once part of the Vale Royal Plantation. According to Keber, the thousand-acre Vale Royal plantation "consisted of the land bounded by the Savannah River, Fahm Street on the east, Augusta Avenue to the south, and what is today West Lathrop Avenue." Originally granted to Pickering and Thomas Robinson in the 1750s, Vale Royal was purchased by Joseph Clay in 1782; "In the 1790s Clay added the distinctive triangular plot of land between Louisville road and Augusta road to Vale Royal."59Ibid., 2, 3.

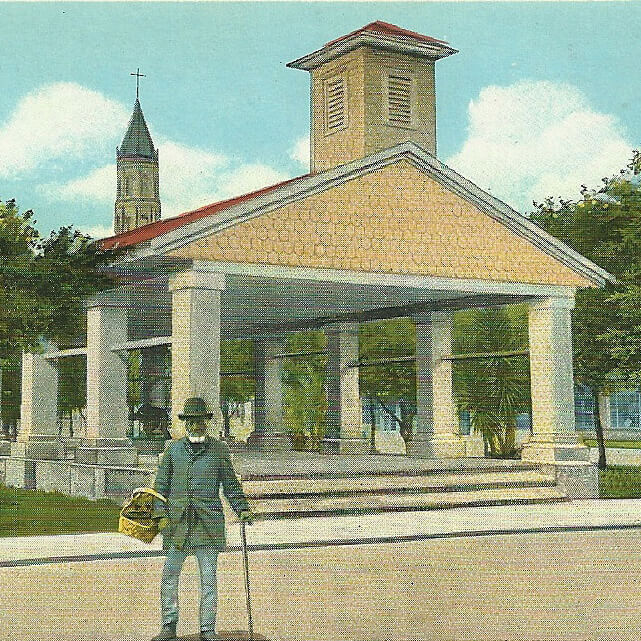

The palimpsest of near-faded and faint dashed lines amid bold city lines and plots excoriated in grid form show in this map alone, the nearly 140 years of Euro- and African-American settlement. Old trails, possibly used by American Indians, became the roads of colonial Americans; Augusta Avenue appears on very early Savannah maps as a trail. Images of several Savannah Jockey Club members from the 1890s, obtained from GHS, show the racetrack and structures: a covered grandstand to one side of the track, shed-like buildings on one side of the "turns" in the track, and smaller (likely timekeeper's) raised platforms. The 1872 Platen map shows two rectangular structures adjacent to the straight stretch of the racetrack, on the north side. These structures are most likely a seating grandstand and covered stables. Doesticks writes that prior to the slave sale, for four days while under inspection by buyers, and for two days during the actual sale, the enslaved were kept in sheds typically used for the horses. He mentions that the slave sale, however, took place in the grandstand:60Doesticks, "Great Auction," 14; for other details of the sale, see also Bell, and Berry, "'We'm Fus' Rate Bargain.'"

This morning they were all gathered into the long room of the building erected as the "Grand Stand" of the Race Course, that they might be immediately under the eye of the buyers. The room was about a hundred feet long by twenty wide, and herein were crowded the poor creatures, with much of their baggage, awaiting their respective calls to step upon the block and be sold to the highest bidder. . . . The room in which the sale actually took place immediately adjoined the room of the Negroes, and communicated with it by two large doors. The sale room was open to the air on one side, commanding a view of the entire Course. A small platform was raised about two feet and a half high, on which were placed the desk of the entry clerks, leaving room in front of them for the auctioneer and the goods.61Doesticks, 14. Mary Beth D'Alonzo (1999) utilizes two of the GHS images of the Savannah Jockey Club in her book on Chatham County streetcars and provides corroborative information in her captions: "The Ten Broeck Race Course was a 1-mile long, horse-racing track at the Fairgrounds of the Agricultural and Mechanical Association of Georgia, located 2.5 miles west of Savannah on the Augusta Road." Mary Beth D'Alonzo, Streetcars of Chatham County (Charleston: Arcadia Press, 1999), 104. My research revealed that a Mrs. Lamar had sold 62 plus acres to the Agricultural and Mechanical Association of Georgia in 1872.

The specific location of the sale can be identified on the actual landscape because of Doesticks' report, the 1872 Platen map, and the 1890s image of the grandstand. A scaled drawing showing the racetrack and the grandstand superimposed on a current aerial photograph (with geographic coordinates) situates the exact slave sale site.

Charles Augustus Lafayette Lamar and "the Weeping Time"

At the GHS, I also searched for "Charles Lamar," and "Ten Broeck," trying to find what, if any, connection Lamar had to the Weeping Time. I discovered a deed, dated 1872, for the sale of the racecourse lands, sold by Mrs. Caroline Lamar, "widow and executrix of C. A. L. Lamar," to the Agricultural and Mechanical Association of Georgia. The Association utilized the Ten Broeck Race Course site for agricultural fairs and allowed the continuation of horse racing there. The deed below shows the four pages from the deed of sale, which indicates that Charles Lamar acquired the property "known as the Race Track" from Ebenezer Jencks according to a deed dated January 31, 1857. This earlier deed strongly suggests that Charles Lamar may have had something to do with the renaming of the site as the Ten Broeck Race Course, since prior to his purchase it was known as "Oglethorpe's Race Track," "Jencks' Old Track" or simply the "Race Track." An advertisement in The Savannah Republican on January 4, 1857, refers to races at the "Ten Broeck course," and this, prior to the inaugural Ten Broeck race, mentioned in the newsmagazine Spirit of The Times as having occurred on January 7, 1857. It is plausible that Lamar was involved in the plans and actions to acquire, reconstitute and name the race track site prior to the inaugural race, and the recording of his purchase of the race course on January 31, 1857.62Specifically, Caroline Lamar sold 62 6/10 acres adjacent to Louisville Road, and an additional forty-five acres south of Augusta Road, and north of "Oglethorpe's Race Track," to the Association, for eight thousand dollars.

Plausibly, slave dealer Joseph Bryan, in anticipation of a large turnout for his sale, reached out to Lamar and requested the use of the Ten Broeck Race Course; alternatively, Lamar may have proffered the racecourse site near Savannah; open, but with stables to house the enslaved, and accessible by Louisville and Augusta roads, and by the Central of Georgia Railroad.

After the archival discoveries at GHS in Savannah, I visited the site of the former racecourse and found it mostly erased and hidden. Bifurcated by highway I-516, half the site is behind walls and a chain-link fence—currently part of a lumber yard owned by The Bradley Plywood Corporation.63Site ownership ascertained from a personal conversation with Tosca Owens, Planner, City of Savannah, November 2007. Owens is the planner who worked behind the scenes to ensure that redevelopment plans for West Savannah would not any longer disregard or be silent about the slave sale at the Ten Broeck Race Course. Across I-516, the other half of the race course site is now part of Bartow Elementary School. The trees shown are very likely growing in the infield of the former race course. At the southeast corner of the former Ten Broeck Race Course site is a paved section of Abbot Street, from which one can see the Central of Georgia railroad tracks.

Commemoration Day

Place reverberates with the history of its unique past. "Place stays, not only in Rememory," writes Toni Morrison, "but out there in the world."64Morrison, Beloved, 43, 44. Nothing brings tangibility to history like walking on the terrain where events took place. On a sunny, calm morning, March 3, 2008, I was present near the former Ten Broeck Race Course location where Savannah and Georgia Historical Society officials unveiled a marker commemorating the slave sale, exactly 149 years earlier.65For journalistic coverage of the commemoration, see Linda Sickler, "Marker honors 'Weeping Time'; Slave sale historical marker is dedicated," Connect Savannah Online, March 11, 2008. http://www.connectsavannah.com/gyrobase/Content?oid=oid%3A6873, accessed October 11, 2008. See also Steve Herrick, "'Weeping Time' Park - Savannah, GA," Waymark, August 14, 2008. http://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WM4EVX, accessed October 11, 2008. See also the Georgia Historical society website for the announcement of the marker, and an embedded interview by the GHS director re: the marker, http://www.slavevoyages.org/, accessed October 11, 2008. The commemoration site is approximately a thousand feet to the northeast from the actual slave sale location. It is a small, triangular lot at the intersection of Augusta Avenue and Dunn Street that the city of Savannah purchased, designed, and developed as a pocket park for the memorial. The site features a few small trees, an existing large oak tree, and lawn grass traversed by a walkway. The marker reads:

Largest Slave Sale in Georgia History:

The Weeping Time

One of the largest sales of enslaved persons in US history took place on March 2-3, 1859, at the Ten Broeck Race Course 1/4 mile southwest of here. To satisfy his creditors, Pierce M. Butler sold 436 men, women, and children from his Butler Island and Hampton plantations near Darien, Georgia. The breakup of families and the loss of home became part of African-American heritage remembered as "the weeping time." The event was reported extensively in the northern press and reaction to the sale deepened the nation's growing sectional divide in the years immediately preceding the Civil War.

Erected by The Georgia Historical Society and the City of Savannah

The mood at the commemoration was pensive, expectant, and quiet. The atmosphere was reminiscent of a funeral with conversations in hushed tones. While most of the assembled were African-Americans, a racially diverse gathering had come to pay their respects to those who had been sold in 1859. Dr. Keber recounted the events, personalities, and range of feelings surrounding the sale. Todd Groce, executive director of the Georgia Historical Society, said that he had received a phone call asking, "Why are you doing this? Why are you putting a marker in that neighborhood? All it will do is stir up anger and resentment." Groce replied, "What we are doing today is being honest about the past."

The day's most stirring comments came from Savannah Mayor Johnson, an African American, who decried the events responsible for the commemoration. He also noted how remarkable it was for a descendant of enslaved Americans to be mayor of this historic city. Johnson wrestled with "a number of emotions," including "anger, over the inhumanity that took place on this site." He had recently met a descendant of one of the Butler enslaved sold at the Ten Broeck Race Course, who told him how it "tore up the family." "Race remains a factor in all decisions made in this country," concluded Johnson. "We're a long way from the Weeping Time, but we have a long way to go."

In Race and Reunion, historian David Blight writes that African Americans were sidelined from the fiftieth anniversary celebrations of the Emancipation. Their only participation in the events at the Gettysburg reunion was to pass out mess kits and blankets. The purposes of the Civil War had been rewritten, with slavery and the fate of blacks scripted out of the narrative:

The war was remembered primarily as a tragedy that forged greater unity, as a soldier's sacrifice in order to save a troubled, but essentially good, Union, not as the crisis of a nation in 1913 still deeply divided over slavery, race, competing definitions of labor, liberty, political economy, and the future of the West . . . It was a white man's experience and a white nation that the veterans and the spectators came to celebrate in July 1913. Any discussion of the wars' extended meanings in America's omnipresent 'race problem' was simply out of place.66David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001), 386, 387.

White reunification, Blight explains, joined hands with white supremacy in "an unblinking celebration," as whites and blacks remained unknown to each other across the divides of separated societies and an anguished past.67Ibid., 391, 397. At the commemoration day ceremonies for the Weeping Time, it was evident that this was a reunion of sorts but a far cry from that at Gettysburg described by Blight.

An Online Commemoration—the Ten Broeck Site Re-imaged

To depict the actual site of the sale, I worked with GIS specialist Michael Page, Geospatial Librarian, of Emory University, and Kyle Thayer, Emory graduate student in Computer Science, to create a composite map and attendant 3-D images at the culmination of this research project, using the aerial photographic software Google Earth, the computer-aided design software AutoCAD, and a three-dimensional design software, Lightwave. Initially, a racecourse meeting the specifications of Ten Broeck was drawn using AutoCAD. Track width and all pertinent dimensions, including the location of the finish line, were obtained with assistance from the Keeneland Equestrian Library in Lexington, Kentucky, and from Belmont Park, home of the New York Racing Association in Elmont, New York. The computer-generated racetrack, with attendant grandstand, was imported into a mapped contemporary image of the site area of the former racecourse. Ultimately, our composite map was created from interrogating and analyzing a historic plat of the Ten Broeck racecourse site, historic maps of Savannah and Chatham county, 1890s photographs of the Savannah Jockey Club members at the Ten Broeck Race Course, and a contemporary aerial photograph of the site.

|  |

| Detail showing Ten Broeck Race Course location, from "Map of part of Chatham County, State of Georgia showing property lines in the environs of Savannah, from the latest surveys," 1897. | Plat of Ten Broeck Race Course site, Savannah, Georgia, 1907. Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society Archives. |

A 1907 plat labeled as the "Plan of the lands of the Agricultural and Mechanical Association [of Georgia] old Ten Broeck Race Course" which I located at the GHS, was scanned, adjusted to the same scale as an aerial photo image of the current site, and imported into a composite image. The 1907 plat shows Augusta Avenue as the northern boundary of the site, and Louisville Road as the southern boundary. Both roads are still in the same locations, and it was relatively easy to see exactly where the plat fit over the contemporary site image. The superimposed map shows I-516 bisecting the site of the former racecourse. To the right of the highway is the current Bartow Elementary School; on the left is the Bradley Plywood Company.

Three historic maps were utilized as guides for the location and orientation of the re-imaged Ten Broeck Race Course site. The 1872 Platen map showed the location of the racecourse between Louisville road and Augusta Avenue. The location from the 1872 Platen map was congruent with the Ten Broeck site's boundaries depicted by the 1907 plat. Prior to creating the composite map, another search was conducted to find other maps that would corroborate the Platen map. At the University of Georgia's map library, I located a map from 1897 labeled, "Map of part of Chatham County, State of Georgia, showing property lines in the environs of Savannah, from the latest surveys." This map showed an oval in the vicinity of Louisville Road and Augusta Road, and a label: "TENBROOK RACECOURSE." This was definitive proof of the racecourse's location at the site, and it corroborated both the 1872 Platen map and the 1907 plat.

A trip to the City Engineers' offices in Savannah yielded a map that most clearly shows the Ten Broeck Race Course. A detail from the Blandford map—created in 1890 after almost a decade of work by Texan Robert A. Blandford, under commission from the City of Savannah—corroborates the earlier maps found during this research and shows an oval track, the words "Ten Broeck Race Course," and importantly, the location of the grandstand—the lieu de memoire of the 1859 sale. The Blandford map locates the grandstand slightly west of center, adjacent the north section of the racetrack, and shows a pathway leading from east of the grandstand through entrance gates to Augusta Avenue.

The detailed map also shows topographic and hydrologic features, labels the "Central Railroad," and even includes mile-markers along both the railroad and Louisville road below the railroad. The mile markers indicate that the racecourse is approximately 2.5 miles west of Savannah, corroborating Doesticks' account of 1859. The Blandford map even shows a fence around the site, and other building structures in addition to the grandstand. The level of engineering detail suggests that this is a very accurate map, and one that our composite map can borrow from in confidence.

The composite image shows the racecourse site from 1859 in juxtaposition to the contemporary site (2023), the approximate location of the former racecourse, and its accompanying grandstand where the enslaved were sold in 1859. The re-imaged, angled buildings at the northwest corner of the track are located in reference to the 1872 Platen map, which was closest in time to the 1859 sale. This most likely approximates the Ten Broeck Race Course site of 1859.

Identifying the location of the grandstands at the former Ten Broeck Race Course with as much specificity as possible allowed the sale of the Butler enslaved to be tied to an almost exact location. Doesticks was clear that the sale was conducted from the long room of the grandstand at the Ten Broeck Race Course. He wrote that the sale room was open on one side, allowing views to the racetrack. The composite map allows an almost exact location of the sale to be identified in the contemporary landscape—on the Bradley Plywood Corporation's property, a quarter mile away from the GHS marker.

Prior to re-imaging the Ten Broeck Race Course grandstand of 1859, historic images of race track grandstands were investigated, and distinctive characteristics borrowed. The 1870 image of the grandstand at Long Branch, Monmouth County, New Jersey, shows some seating covered, and some open to the elements. This image also shows windows, suggesting rooms, mostly used for concessions, underneath the grandstands. It is likely that such rooms existed underneath the Ten Broeck grandstand that Doesticks referred to as the slave holding, and sale, rooms. It also shows the cone-roofed judges' booths astride the racetrack. An 1865 Winslow Homer sketch of Saratoga, New York's racecourse and grandstand shows a tarp-topped grandstand, and racing enthusiasts, some under, and others outside, the covered area. A postcard image, likely from the early 1900s, of a racetrack in Maxwellton, St. Louis, Missouri shows clearly the judges' booths, the fencing that kept spectators off the horse track, and spectators standing in the open. A 1973 image from Ak-Sr-Ben Race Track in Omaha shows a grandstand with a sloping roof. Comparing the Winslow Homer sketch of 1865 to this more contemporary image, it appears that the general structure of horse race grandstands have not changed much; they are open air structures, partially covered, and may have rooms below the stands.

Based on the reviewed images of horse tracks and grandstands, and on Doesticks's description that there were rooms in the grandstand, at least one measuring 100 x 20 feet, an image of a grandstand was created using Lightwave, a computer software. The view shows a grandstand with partially covered seating, the horse racing track, and judges booths adjacent the track. The location of the re-imaged grandstand in juxtaposition to the current landscape and buildings is telling. Behind the re-imaged grandstand is the entrance drive into the current Bradley Plywood Corporation property, suggesting that the former grandstand (the actual sale) site is to a visitor's immediate left upon entry into the Bradley compound from the north entrance gate. The actual site of memory—the grandstand, the lieu de memoire—should be marked. Its approximate coordinates are: Latitude: N 32° 5' 12.4332" Longitude: W 81° 7' 49.5444". The dark, shadowed area on the ground floor underneath the grandstand in the three-dimensional image of the re-imaged site suggests the room that Doesticks mentioned: "The room in which the sale actually took place immediately adjoined the room of the Negroes, and communicated with it by two large doors. The sale room was open to the air on one side, commanding a view of the entire course . . ."

A final trip to Savannah, in January 2010 in search of the deed of sale from Ebenezer Jencks to Charles Lamar, referred to in the deed of sale between Lamar's widow Caroline and the Agricultural and Mechanical Association of Georgia yielded the deed, replete with a sketch of the Ten Broeck racetrack site. The sketch map shows bearings and distances which help confirm the site's location. The south boundary of the site has a bearing: S 76 ¾ E. 40.34. This means that the direction of the line which represents this edge of the property is 76 degrees and 45 minutes (3/4 of 60mins) east from true South, at a distance of 4034 feet. Surveyors of that era used 100-foot-long chains as standard units of measurement, so a distance of 4034 feet would be recorded as 40.34 chains. The west boundary had a bearing of S 14 ½ W, at 1576 feet. The north boundary's bearing was N 76 E at 40.30 (4030 feet). The east boundary's bearing was N 14 ½ E, at 1543 feet.

Space Emptied and Peopled

Michel Foucault writes that if we listen, we will hear the abundance of history trapped or wedged in the spaces of "words without language"—spaces "peopled and empty at the same time." The search for the Ten Broeck Race Course attempts to "lend an ear" to the "dull sound[s] from beneath history," the hidden history of one landscape of slavery.68Michel Foucault, History of Madness, ed. Jean Khalfa; trans. Jonathan Murphy and Jean Khalfa (London: Routledge, 2006), xxxi–xxxii. Research led through archives and onto the landscape. The site of perhaps the largest sale of enslaved persons in North America, although erased, hidden, and silent, endures in the narratives and historical memories of some Savannah residents. The Ten Broeck sale site is one of many silent, erased, or hidden landscapes of enslavement—tangible places to be rediscovered, re-narrated, re-imaged, and recreated for their historical importance. In listening, I have heard the murmurs of the landscape, empty and peopled at the same time, haunted by those who were sold here.69Ibid., xxxi–xxxii.

Acknowledgements

This work has benefited from numerous people. The author would like to acknowledge especially the following that helped in diverse ways with this essay: Dr. Allen Tullos, editor, and the editors at Southern Spaces—Sarah Toton, Katie Rawson, Franky Abbott, and Mary Battle; the anonymous readers for Southern Spaces; Dr. Michael Moon, Emory University Professor, and my fall, 2007 cohort in Dr. Moon's Foundations course; Naomi Nelson, Kathy Shoemaker, Lloyd Busch, Betsy Patterson and Michael Page, Emory Libraries; Dr. Martha Keber; Allynne Tosca Owens, City of Savannah Department of Economic Planning; Monifa Johnson; David Anderson and Derrick Hillery, Chatham County Department of Engineering; Tom Hardaway, UGA Map Library; all the staff of the Georgia Historical Society, and Kyle Thayer.

Recommended Resources

Text

Aiken, Charles S. The Cotton Plantation South Since the Civil War. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Anquandah, K. J. Castles and Forts of Ghana. Paris: Atalante Ghana Museums and Monuments Board, 1999.

Bancroft, Frederick. Slave Trading in the Old South. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996.

Basso, Keith H. Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape And Language Among The Western Apache. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996.

Beardsley, John (with contributions by Roberta Kefalos and Theodore Rosengarten, principal photography by Len Jenshel). Art and Landscape in Charleston and the Low Country: A Project of Spoleto Festival USA. Washington, DC: Spacemaker Press, 1998.

Bell, Malcolm Jr. Major Butler's Legacy; Five Generations of a Slaveholding Family. Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1987.

Blight, David W. Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001.

Brundage, W. Fitzhugh. The Southern Past: A Clash of Race and Memory. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005.

Calonius, Erik. The Wanderer: The Last American Slave Ship and the Conspiracy That Set Its Sails. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2006.

Carney, Judith. Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivation in the Americas. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

D'Alonzo, Mary Beth. Streetcars of Chatham County. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Press, 1999.

DeGraft-Hanson, Kwesi. "The Cultural Landscape of Slavery at Kormantsin, Ghana." Landscape Research 30, no. 4 (2005): 459–481.

Dizikes, John. Sportsmen and Gamesmen. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1981.

Dusinberre, William. Them Dark Days; Slavery in the American Rice Swamps. Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 2000.

Fraser, Walter J. Savannah in the Old South. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2003.

Hayden, Dolores. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995.

Hilliard, Sam B. "The Tidewater Rice Plantation: An Ingenious Adaptation to Nature." Coastal Resources, Geoscience and Man, 12, (1975): 57–66. ed. H.J. Walker. Baton Rouge, LA: The School of Geoscience.

Johnson, Walter, ed. The Chattel Principle: Internal Slave Trades In The Americas. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004.

Kemble, Frances Anne. Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838–1839. ed, John A. Scott. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1961.

Lane, Mills B. ed. Neither More nor Less than Men: Slavery in Georgia: A Documentary History. Savannah: Beehive Press, 1993.

Littlefield, Daniel C. Rice and Slaves: Ethnicity and the Slave Trade In Colonial South Carolina. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1981.

Meinig, D.W. ed. The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes; Geographical Essays. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Morrison, Toni. Beloved, A Novel. New York: Plume, 1987.

Muir, Richard. Approaches to Landscape. Lanham, MD: Barnes & Noble, 1999.

Nash, Linda. "The Agency of Nature or the Nature of Agency?" Environmental History, 10, no. 1 (2005): 67–69.

Phillips, U. B. American Negro Slavery. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994.

Singleton, Theresa Ann. The Archaeology of Afro-American Slavery in Coastal Georgia: A Regional Perception of Slave Household and Community Patterns. University of Florida: PhD Diss., 1980.

Smith, Julia Floyd. Slavery and Rice Culture in Low Country Georgia 1750–1860. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1985.

Stewart, Mart A. "What Nature Suffers to Groe": Life, Labor and Landscape on the Georgia Coast, 1780–1920. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1996.

Vlach, John Michael. Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

Wells, Tom Henderson. The Slave Ship Wanderer. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1967.

Web

"Africans in America, America's Journey through Slavery." PBS. 1999. www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/.

Baily's Magazine of Sports and Pastimes, Volume 8. London: A.H. Baily & Co., 1864. Book digitized by Google. http://books.google.com/books?id=dB0GAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA55&dq=richard+ten+broeck#PPA54-IA2,M1.

Berry, Stephen W. II. "Butler Family." The New Georgia Encyclopedia. 2002. www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-617.

"Enslaved People of Butler Island." Georgia Historical Society. March 4, 2019. https://georgiahistory.com/ghmi_marker_updated/enslaved-people-of-butler-island/.

Herrick, Steve. "Weeping Time" Park - Savannah, GA." Waymarking. August, 14, 2008. http://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WM4EVX.

Keyes, Allison. "The ‘Clotilda,’ the Last Known Slave Ship to Arrive in the U.S., Is Found." Smithsonian Magazine. May 22, 2019. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/clotilda-last-known-slave-ship-arrive-us-found-180972177/.

SlaveVoyages. Accessed April 19, 2023. http://www.slavevoyages.org/.

Sickler, Linda. "Marker Honors 'Weeping Time': Slave Sale Historical Marker is Dedicated." Connect Savannah Online. March 11, 2008.

http://www.connectsavannah.com/gyrobase/Content?oid=oid%3A6873.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Q. K. Philander Doesticks, "Great Auction Sale of Slaves at Savannah, Georgia, March 2d and 3d, 1859," The New-York Tribune, March 9, 1859, 8. |

|---|---|

| 2. | W. Fitzhugh Brundage, The Southern Past: A Clash of Race and Memory (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005), 4. |

| 3. | Kwesi DeGraft-Hanson, "The Cultural Landscape of Slavery at Kormantsin, Ghana." Landscape Research 30, no. 4 (October 2005): 461. |

| 4. | Keith H. Basso, Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language among the Western Apache (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996). |

| 5. | The precise sale site is a quarter mile away, and not visible, from the commemorative marker. |

| 6. | Richard Muir, Approaches to Landscape (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1999). |

| 7. | D. W. Meinig, ed., The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes: Geographical Essays (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), 7. |

| 8. | Butler resided mainly in Philadelphia, but spent a few months out of some years visiting his Georgia plantations inherited from his maternal grandfather, Major Pierce Butler. The major's will stipulated that for his grandson(s) to inherit his properties they had to change their last name from Mease, to Butler. For brief biographic details of both Mease Butler and Major Butler, see The New Georgia Encyclopedia (http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-617); for complete biographic information about the Butler family, see Malcolm Bell, Jr., Major Butler's Legacy: Five Generations of a Slaveholding Family (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1987). Because Butler visited the plantations infrequently, he depended on overseers like Roswell King, Sr., and his son Roswell, Jr., for daily management. Between them, the two Kings managed the Butler plantations in succession, from 1803 through the 1840s, serving three generations of Butlers. |

| 9. | Bell, Major Butler's Legacy, 339. See also, Africans in America, a 1998 PBS documentary, online at www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia. |

| 10. | Bell, Major Butler's Legacy, 511. |

| 11. | Ibid., 332. |

| 12. | Doesticks, "Great Auction," 4. |

| 13. | Doesticks, "Great Auction," 12–13; Bell, Major Butler's Legacy, 329; Daina Ramey Berry, "'We'm Fus' Rate Bargain'; Value, Labor and Price in a Georgia Slave Community," The Chattel Principle: Internal Slave Trades in the Americas, ed. Walter Johnson, (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004), 65. |

| 14. | Doesticks, "Great Auction," 9. Also, Bell, Major Butler's Legacy, 329. |

| 15. | Doesticks, "Great Auction," 5, 19. |

| 16. | Ibid., 21, 27, 28. |

| 17. | Ibid., 22, 23. |

| 18. | Ibid., 22–23. |