Overview

In an earlier commentary for Southern Spaces, Dorothy Moye described the widespread use of the X-code, an iconic graphic applied by search-and-rescue teams in 2005 post-Katrina New Orleans. Here, in a virtual exhibition, Moye presents X-code images selected from the work of more than twenty-five photographers in the intervening five years. Visually striking and emotionally compelling, the X-code speaks through its sheer numbers, its rhythmic repetition across the curving network of city streets, its narrative traces of ciphered messages, and its graphic directness.

"Katrina + 5: An X-code Exhibition" was selected for the 2009 Southern Spaces series "Documentary Expression and the American South," a collection of innovative, interdisciplinary scholarship about documentary work and original documentary projects that engage with regions and places in the US South.

Introduction

In the five years since August 29, 2005, when Hurricane Katrina wreaked havoc along the entire Gulf Coast and the subsequent failure of New Orleans’ levee system altered the history and the face of the city, thousands of professional and amateur photographers have sought to corral their memories and impressions of Katrina and its aftermath. Torrents of still and moving images speak to the immensity of the event that poet and New Orleans resident Andrei Codrescu refers to as “the most photogenic disaster in American history since the Civil War.”1Codrescu, Andrei, cover blurb for Jane Fulton Alt, Look and Leave: Photographs and Stories from New Orleans’s Lower Ninth Ward. Center for American Places at Columbia College Chicago, 2009.

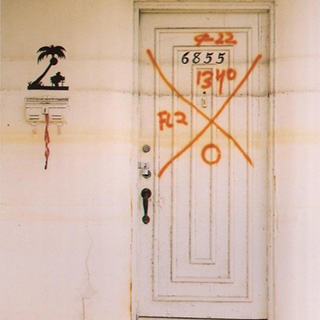

The virtual exhibition presented here revolves around one iconic form in the visual landscape of Katrina in New Orleans—variants of the X-code left by searchers as they systematically covered the city, critically pertinent markings applied to visited houses and buildings. “Paint fades, archives endure,” reads a promotional poster from the Hurricane Digital Memory Bank.2http://hurricanearchive.org/. The Hurricane Digital Memory Bank uses electronic media to collect, preserve, and present the stories and digital record of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. George Mason University’s Center for History and New Media and the University of New Orleans, in partnership with the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History and other partners, organized this project. Displaying three progressively fainter versions of the ubiquitous spray-painted signs that greeted residents returning to the city, the poster solicits electronic recollections for the Memory Bank as it features the X-code graphic that became an indelible symbol on the streets of New Orleans after Katrina. Although outdoors the codes are fading and disappearing, the X-code photographs, recorded by anyone in the vicinity during the last five years with a camera, constitute a documentary archive with tales to tell.

The enigmatic X-code messages could appear threatening in their mystery, especially upon structures of personal significance to the viewer, while the cumulative power of thousands of these markings communicated the enormous scale of what had occurred. In addition to wind and water damage, infrastructure destruction, uncertainty about the fate of family, neighbors, and friends, and a complete disruption of familiar life, the appearance of the codes added another unknown—a mysterious graphic with alphanumeric markings spray-painted on homes, schools, businesses, and places of worship. Some residents immediately deciphered their meanings. There were also interpretations available such as a New Orleans Times-Picayune's September 17, 2005, front-page article.3Perlstein, Michael, “For Tales of Life and Death, the Writing’s on the Walls,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, September 17, 2005, p.1. Too often, though, the message sent was not the message received. Finding an X-code on his home, University of New Orleans professor Frederick Barton spoke for many when he commented, "That first day and for many thereafter, we did not understand what the mark meant. In fact, I am not sure that I do yet."4Barton, Frederick. E-mail correspondence, November 24–25, 2008.

Artist Elyse Defoor described her first visit back to the city in early 2006: “Instead of being macabre symbols X-ing out all presence, the Xs were in fact a coding system used by the search and rescue teams. . . . The discovery that what I had perceived to be marks of annihilation were in fact useful tools did not diminish the visceral experience of seeing those Xs scrawled across my beloved city. For me, they will always be stigmata of immense loss and unexpected death." 5Defoor, Elyse. E-mail correspondence, May 8, 2008.

How did others interpret the X-code?

". . . there was something almost biblical about those markings on all the front doors around here. . ."6Rose, Chris. "Badges of honor: Part historic preservation, part act of defiance, the spray-painted markings of Katrina rescue workers remain prominently displayed on many reoccupied New Orleans homes." New Orleans Times-Picayune, July 24, 2007.

“. . . conjuring a cross between the Vévé signs of voudun and a kind of military coroner's occupation.”7Spitzer, Nick. E-mail correspondence, June 16, 2009.

“Now each house bore runic signs in orange spray paint. . .”8Piazza, Tom. Why New Orleans Matters, New York: Regan Books, 2005, 125.

“Ah, the X—truly the most powerful symbol, for better or worse, that we have, I think.”9Smith, Barbara Lee. E-mail correspondence, September 15, 2009.

“For Tales of Life and Death, the Writing’s on the Walls”10Perlstein, loc.cit.

“. . . end-of-the-world eerie.”11Baker, Ellen. E-mail correspondence, August 27, 2009.

“. . .alarming . . . invasive . . .a violation . . .lawless graffiti . . . disrespectful . . .”12These are words and phrases that cropped up repeatedly in varied conversations.

The images gathered in this virtual exhibition entertain all these interpretations and more. Those recorded in 2005 and 2006 were most often found on grievously damaged properties. Some stakeholders returning were disturbed by the memories and symbolism, and quickly painted over, scrubbed and scraped off the codes, or discarded the offending graphics as they replaced doors, windows, or siding. Others were later removed as a concession to appearances for insurance purposes. Some residents made a conscious decision to retain the codes as part of the provenance of that structure or a memorial to the event. Shrine-like tableaux incorporate some X-code markings. Still others remain as unwitting testimonials on neglected, deteriorating structures barely touched since 2005, default memorials and commentaries.

The repetition of the X-code on house after house after house on mile after mile after mile of streets composed a powerful architectural narrative during the weeks following the storm as they appeared on structures spanning the socioeconomic mix of the city. “This [official graffiti] was the now-famous ‘X’ in a fluorescent orange or yellow that on the Caribbean-style color schemes of the homes in New Orleans made for some startling graphics,” recalls New Orleans artist Thomas Mann. “I began documenting these signs immediately and continue to do so. I found these markings to be visually interesting and full of import."13Mann, Thomas. Storm Cycle: An Artist Responds to Hurricane Katrina. Bellevue, Washington: Bellevue Art Museum, 2006, 7.

Codes Decoded

Mann was on vacation when the storm struck on August 29, 2005, so, like viewers all over the world, he watched television coverage of the unfolding tragedy in his city. He captured a screen image of a reporter sketching the official code in a notebook while explaining the search process.

Cynthia Scott's photo provides a clear illustration of the code in Faubourg Marigny in 2005. In addition to its adherence to the manual’s instructions, it stands out because, as the artist observes, “It appears the search team made an effort to coordinate their markings with the color scheme already in place.”

Although there is an official code system outlined in the Urban Search & Rescue team manuals used since the early 1990s, the code was not familiar to most citizens. With some 80% of New Orleans’ structures marked, the code commanded unprecedented attention.14http://www.fema.gov/, Urban Search and Rescue (US&R) Response System Field Operations Guide, FEMA, September 2003 (US&R-2-FG), p. 56.

Single slash drawn upon entry to a structure or area indicates search operations are currently in progress. The time and TF identifier are posted as indicated.

Crossing slash drawn upon personnel exit from the structure or area.

Distinct markings will be made inside the four quadrants of the X to clearly denote the search status and findings at the time of this assessment.

The marks will be made with carpenter chalk, lumber crayon, or duct tape and black magic marker.

LEFT QUADRANT — US&R TF identifier

TOP QUADRANT — Time and date that the TF personnel left the structure.

RIGHT QUADRANT — Personal hazards.

BOTTOM QUADRANT — Number of live and dead victims still inside the structure.

["0" = no victims]

The most striking portion of the code is the lower quadrant of the X, denoting the number of survivors or bodies.

Urban Search & Rescue (US&R) task forces, certified by FEMA, are highly trained first responders, who specialize in response to structural collapse, and who may be deployed in disasters either by FEMA or by sponsoring states. There are twenty-eight US&R task forces throughout the United States. While the codes are specified as their communication tool, in the chaos following the storm, first responders from other agencies often used a variant of the code, improvised their own, or may not have marked at all.

Another frequently encountered graphic is the X (or slash) in a square. This code is also an official US&R marking warning of structural instability and is diagrammed in the FEMA manual.15Ibid., p. 54

National Urban Search and Rescue Response System

Structure is accessible and safe for search and rescue operations. Damage is minor with little danger of further collapse.

Structure is accessible and safe for search and rescue operations. Damage is minor with little danger of further collapse. Structure is significantly damaged. Some areas are relatively safe, but other areas may need shoring, bracing, or removal of falling and collapse hazards. The structure may be completely pancaked.

Structure is significantly damaged. Some areas are relatively safe, but other areas may need shoring, bracing, or removal of falling and collapse hazards. The structure may be completely pancaked. Structure is not safe for search and rescue operations and may be subject to sudden additional collapse. Remote search operations may proceed at significant risk. If rescue operations are undertaken, safe haven areas and rapid evacuation routes should be created.

Structure is not safe for search and rescue operations and may be subject to sudden additional collapse. Remote search operations may proceed at significant risk. If rescue operations are undertaken, safe haven areas and rapid evacuation routes should be created. Arrow located next to a marking box indicates the direction to the safe entrance to the structure, should the marking box need to be made remote from the indicated entrance.

Arrow located next to a marking box indicates the direction to the safe entrance to the structure, should the marking box need to be made remote from the indicated entrance. Indicates that a HAZMAT condition exists in or adjacent to the structure. Personnel may be in jeopardy. Consideration for operations should be made in conjunction with the Hazardous Materials Specialist. Type of hazard may also be noted.

Indicates that a HAZMAT condition exists in or adjacent to the structure. Personnel may be in jeopardy. Consideration for operations should be made in conjunction with the Hazardous Materials Specialist. Type of hazard may also be noted.

The mysterious TFW Code

A different form of code seen frequently in the Upper Ninth Ward, is the mysterious TFW code. There continues to be much speculation about the identity of the search team who left these markings. There are two forms of this code—one is a simple spray-painted lettering of TFW with the date, as seen in Andrea Booher's image above of guardsmen, taken on September 20.

Thomas Mann's photographs shows another more elaborate TFW iteration, a circular format with a date and information, plus a version of the TFW expanded into TFWldcts.

Jane Fulton Alt’s photograph shows a similar circular configuration, but without the expansion to Wldct.

How is this code interpreted? The exact meaning is a source of great speculation among residents and visitors, and after five years this speculation is taking on the dimensions of an urban legend. Here are a few guesses:

Toxic Flood Water

Totally Full of Water

Texas Fish & Wildlife

Tennessee Fish & Wildlife

Totally (x-rated)

Team Forth Worth

Task Force Wyoming

Task Force Wildcat

Fire department personnel told Bob Thomas, director of the Center for Environmental Communication at Loyola University, that this code stands for Task Force Wildcat.16Thomas, Robert A. E-mail correspondence, June 22, 2010. But not everyone agrees with this interpretation. “Amazing how hard it is to find info,” said Thomas four-and-a-half years later. “But—while they were doing the S&R, no one was even thinking of keeping records.” Jackson Barracks historian Thomas M. Ryan, LTC (ret) of the Louisiana National Guard (LNG), reports, “My source indicates that TFW was the mark used by Task Force Wyoming which coincides with my post-K memory bank. Hope that this helps.”17Ryan, Thomas M. LTC (ret). E-mail correspondence, June 27, 2010. Another LNG source confirms this interpretation. However, an online publication dated September 19, 2005, identifies the elusive group as a combination of the West Virginia and Oregon National Guards, signing themselves as TFW (Task Force Wildcat).18Sydenstricker, Capt. L. Paula, 153rd Mobile Public Affairs Detachment, "West Virginia National Guard Plays Vital Role in the Infantry Mission," Defense Video & Imagery Distribution System (dvids), http://www.dvidshub.net/news/3054/west-virginia-national-guard-plays-vital-role-infantry-mission, September 19, 2005

KEN

Structures marked with KEN were specifically searched for bodies by Kenyon International Emergency Services, a Texas company that provided mobile morgue services. The codes indicate that two bodies were removed from this structure on October 2, 2005. The date confirms that the morgue service was still operating thirty-four days after the storm.

Other markings

“Cans of DayGlo spray paint were handed out by FEMA to second and third responders,” reports historian Douglas Brinkley. "The primary goal was to mark in bright red or orange which buildings had been searched and whether bodies were found."19Brinkley, Douglas, The Great Deluge: Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans, and the Mississippi Gulf Coast. New York: Harper Perennial, 2007. (First published 2006, William Morrow.) When these self-deployed teams and individuals marked, the meaning of the resulting spontaneous codes usually left town with the painters.

Frederick Barton describes encountering a unique interpretation of the code: “At the time of our first return to the city, we assumed the mark on our exterior wall was planned—the tail indicated hurricane damage and distinguished itself from other marks that FEMA used to indicate earthquakes or fire or other kinds of disasters. Now, however, I suspect the tail had no meaning whatsoever and was just the product of a guardsman standing on uneven ground and trying to make a circle that he didn't do correctly.”20Barton, loc. cit.

Probable interpretations of other commonly seen markings:

NE – the structure was Not Entered

SELA – Southeast Louisiana (a search unit)

F/W – seen most often with animal rescue markings and is believed to indicate that Food and Water were left for pets.

0 A, 0 D – no one was found, alive or dead

3 LV, or 3 L – 3 live persons found

HSUS—Humane Society of the United States

SPCA—Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals

Codes Elsewhere

X-codes have been used in responding to disasters across the country through the years. Informal speculation is that they were developed after the California earthquakes in the early 1990s. My first awareness of these markings was in 1999 in Greenville, North Carolina, after devastating floods from Hurricane Floyd’s torrential rains had inundated the eastern half of that state destroying many properties near creeks and rivers. More documentation of the codes used elsewhere followed a March 15, 2008 tornado in Atlanta, Georgia, when a variant of the spray-painted code was used sparingly in the affected Cabbagetown neighborhood,and in 2008 when Hurricane Ike hit the Texas Gulf coast.

First Responders

Photographers contracted by FEMA in August, September, and October of 2005 took the images in the following slide show. They accompanied the Urban Search & Rescue teams searching the city, often in boats.21All images marked "FEMA News Photo" are works of a Federal Emergency Management Agency employee, taken or made during the course of an employee's official duties. As works of the US federal government, all FEMA images are in the public domain.

The earliest dated codes and photographs are August 30, 2005, by Marvin Nauman and Jocelyn Augustino, documentation that the Urban Search and Rescue teams were at work in some parts of the city the day after the storm had passed.

FEMA-contracted photographers with their authorized access captured images of codes applied to rooftops when these would have been the only visible portions of a home. They captured images of personnel painting the codes, leaving notices explaining the search in mailboxes, entering to search, of codes on structures that had floated to the middle of streets or landed atop vehicles, of boats on roofs and pieces of houses jumbled together, of successive lines marking where the water had settled, and the wreckage left behind when the water had receded. Their archives are remarkable for their on-the-scene immediacy. This slide show proceeds in chronological order, according to FEMA dating.

Maps of New Orleans

Two maps from the Community Data Center illustrate how New Orleanians think spatially about their city. The New Orleans Planning Districts map roughly corresponds to popular designations of city geography. The titles for these planning districts are used for the organization of the images that follow.

The second map, Neighborhoods in Orleans Parish, indicates the familiar neighborhood names included within each planning district. For example, the Bywater Planning District includes the Bywater, St. Claude, Florida Avenue, Desire, St. Roch, and Marigny neighborhoods.

In considering New Orleans map directions, the local cardinal points, rather than North-South-East-West, are usually described as Riverside-Lakeside-Upriver-Downriver, although sometimes Uptown-Downtown are substituted. It is a local convention that simplifies directions that defy logic—for example, Algiers on the West Bank, is actually southeast of the French Quarter.

Campanella’s map of flood depths uses approximately the same neighborhood designations as those above and helps to interpret the variations in the flood’s effects between neighborhoods.

Lower Ninth Ward, 2005–2006

The hurricane's and flood's catastrophic effects on the Lower Ninth Ward were chronicled extensively by the media. This neighborhood of generational families and homeowners is bordered by both the Industrial Canal and the Mississippi River. A breach in the Industrial Canal levee near the Claiborne Avenue bridge was responsible for a tidal wave of rushing water destroying all in its path. The word "Lower" in Lower Ninth Ward does not refer to elevation, but designates that the area is below, or downriver from the Industrial Canal (the Upper Ninth is above, or upriver from the Canal).

FEMA-contracted photographers and a few others with special access worked in the area in the early post-storm days. Photographer Jane Fulton Alt recorded her impressions in November during time off while she served as a counselor in the Look and Leave program. She accompanied homeowners on their first—and sometimes only—emotional trips back into the neighborhood to inspect their properties. Her off-time pilgrimages through the same territory documented what she had seen.

Hurricane Rita followed close on the heels of Katrina and the city felt the effects of the edge of that storm on September 22, 2005. Portions of the Lower Ninth reflooded and there followed a second round of searching and marking. Some buildings bear several sets of markings, layers of dates and data. In these photographs, as well as those from Lakeview and St. Bernard, the positions of houses, cars, boats, trees, and other objects testify to the furor of the water's force.

One house, three photographers

Before it was demolished and removed, at least three photographers documented this home swept from its foundations by the Industrial Canal levee breach: FEMA's Andrea Booher in October, Jane Fulton Alt in November, and Lauren Tilton in January.

Each photographed the house from a different angle, but with the prominent coding of several searches recorded. Booher's close-up of a memorial message and a mourning wreath illustrates a spontaneous breaking of the code with a personal message from friends and relatives, clarifying the layered information to emphasize that some of the occupants did not survive.

Street Scene: Lizardi and Dauphine Streets, Holy Cross

Ian J. Cohn photgraphed three residences clustered around the intersection of Lizardi and Dauphine Streets in the Holy Cross neighborhood, a microcosm of the Lower Ninth Ward.

Street Scene: North Rampart Street and Jourdan Avenue, Holy Cross

Also in Holy Cross, Cohn recorded these houses near the North Rampart Street and Jourdan Avenue intersection.

Top left, Tree in house near N. Rampart Street. Top center, 4812 N. Rampart Street near Jourdan Avenue. Top right, 1005–1007 Jourdan Avenue. Bottom left, 1009 Jourdan Avenue near N. Rampart Street. Bottom right, 715 Jourdan Avenue near Royal. Holy Cross, New Orleans, Louisiana, November 4, 2005. Photographs by Ian J. Cohn. © Ian J. Cohn.

Street Scene: Forstall Street, Holy Cross to Lower Ninth Ward

Following Forstall Street from near the Mississippi River in Holy Cross into the northern end of the Lower Ninth Ward, Ian Cohn provides a view of moving down a street paralleling the Industrial Canal.

By early 2006 access to the Lower Ninth was less restrictive and photographers recorded structures that appeared untouched since the code painters had left their marks. Cohn photographed the same home in September of 2006 that Brian Gauvin had captured the preceding October, still canted against the trees and utility poles. Still untouched buildings that had floated from their foundations were scattered across the landscape. Vehicles lay atop and beneath wandering houses. Refrigerators hung suspended on power lines. Random items were strewn and abandoned before ruined houses. There were grim and hopeful animal rescue markings, defiant messages of identity, and always the code.

Lakeview, 2005–2006

The force of the storm surge traveled through Lake Ponchartrain, breached the 17th Street Canal, and devastated the upper middle class neighborhood of Lakeview. Developed in the twentieth century on drained and filled-in swamp and marshland, Lakeview is one of the city’s younger neighborhoods as well as one of the lowest points in the entire metro area. Less visible in the media reporting of the storm than the Lower Ninth Ward, Lakeview’s homes and residents were no less drastically affected by the levee failures. As in other neighborhoods, homes were built within yards of the levee walls (the rise visible behind the homes in the top left and bottom right images.)

Street Scene: Near the 17th Street Canal Levee breach

Street Scene: Near West End and Veterans Boulevards

Moving through a section of Lakeview, Brian Gauvin photographed several structures near the intersection of West End and Veterans Boulevards.

Scenes of devastation here are similar to those of other neighborhoods, except that the architecture is more recent, many structures are larger, and the water lines are much more visible.

Street Scene: West End Boulevard, Lakeview

Moving down West End Boulevard, Ian J. Cohn photographed several residences.

Street Scene: West End and Harrison Boulevards

Brian Gauvin and Ian J. Cohn photographed the same house near West End and Harrison Boulevards approximately six weeks apart.

Probably applied from a boat, the X-code between the windows dated September 8 is high above the water lines. Cohn’s image shows a later-dated code on the front door, indicating a second crew visited on September 24, after Gauvin's photograph, perhaps to check areas that were inaccessible earlier. The November 4 photo shows the mud line clearly delineated.

Gentilly

Gentilly’s flooding came from all sides—the Industrial Canal on the east, but primarily from the London Avenue Canal that runs through the center of the area, with failed levees on both east and west banks. Like Lakeview, this is one of the more recently developed parts of the metro area, with most structures dating from the twentieth century. The flood here was more than ten feet deep and covered many of the ranch-style homes. When slowly receding waters drained away, catastrophic mold and mildew proved as damaging as moving water.

In this neighborhood there is a photograph (slide 12) by Collette Fournier showing a code not recorded elsewhere—a factory wall shows a slash with a circle. The X was not completed and the circle indicates that a team left the building without completely searching it.

Before and After in Gentilly

In 2005 Lauren Tilton photographed a church with a toppled steeple and a code marked from boat height. She returned to the same location in 2010 to record a repaired steeple base and a fading code.

Bywater, 2005–2006

The Bywater district, known alternately as the Upper Ninth Ward, encompasses six diverse neighborhoods. The riverside neighborhoods on higher ground, Bywater and Faubourg Marigny, with their vivid architectural palettes (and a contrasting spectrum of markings), were not as drastically affected by floodwaters as neighborhoods such as St. Roch and St. Claude in the lakeside direction. Standard codes and unusual notes ("Bunny gone" and "1 chicken rescued") are interspersed with official notices from FEMA threatening impossible-to-meet deadlines. Search notations continued into October.

Richard Campanella wrote of discovering the code on his Bywater home, and his attachment to the graphic: “I first saw our X upon returning to our house on September 14, twelve days after my wife and I fled the flooded city. The sight startled me: blood red, perfectly centered, on the pastel pink facade of a 112-year-old house. A professional graphics designer could not have created a more perfect icon of the Katrina catastrophe: striking, well proportioned, loaded with relevant information without being noisy, hectic yet methodical. It was so ugly, it was nearly beautiful.

“I conserved my X for over two years as a historical relict (much to the consternation of my wife), but finally painted it over in December 2007 when rumors circulated that insurance companies were passing actuarial judgments on houses based on visual evidence of their occupancy . . . It pained me to paint it over, but honestly I haven't missed it since. Perhaps I over read its symbolic importance; perhaps I let the pragmatic trump the abstract . . . or perhaps time is softening the searing memories of that time.”22Campanella, Richard. E-mail correspondence, February 2, 2010.

Voudou references

Observers have compared the codes to voudou23Louisiana French spelling. Alternates forms: voudun, vodou, voodoo. markings, and specifically to vévés (linear symbols used to summon spirits in voudou’s religious ceremonies).24Saint-Lot, Marie-Jose Alcide. Vodou, a Sacred Theatre: The African Heritage in Haiti. Coconut Creek, Florida: Educa Vision, 2003, 105. Cynthia Scott contrasts a structural instability code to both a hieroglyph and a voudou pictograph. Paul Conlan has photographed what is probably an authentic vévé next to a Marigny home’s X-code.

New Orleans East

New Orleans East (or Eastern New Orleans) was developed near the lakefront on large swaths of low-lying reclaimed wetlands in the second half of the twentieth century. During Katrina the area was inundated from several sources, including the notorious MR GO canal (Mississippi River Gulf Outlet) on its southern border. New Orleans East straddles the I-10 entrances to the city approaching from the east. The devastation on both sides of the freeway, of see-through apartment complexes, deserted shopping centers, and blue-tarped homes greeted motorists entering the metro area for several years following the storm.

The photographers working in New Orleans East captured images of devastated churches, abandoned apartments, and returning residents. American Studies scholar Lynnell Thomas (slide 6) links a photograph of her own home’s X-code to her neighborhood homeowners’ association website in Kingswood Subdivision, chronicling the mutual support of a recovering community.

Mid-City

Mid-City's name describes its location. Bayou St. John, a natural stream without levees is the only waterway in Mid-City. It overflowed with storm surge entering from Lake Ponchartrain. Much of the area's flooding, however, resulted from influx from the Industrial Canal and the levee breaks affecting Lakeview and Gentilly.

Famed Canal Street and its businesses, schools, places of worship, and surrounding residential areas suffered varying depths of flooding. Geological features running through the area such as the slightly higher Metairie and Esplanade ridges took on much lower water levels.

Street Scenes: Moss Street, Faubourg St. John

In 2010 Cynthia Scott recorded several residences on Moss Street bordering Bayou St. John, providing a microcosm of Faubourg St. John, a neighborhood recovering, but with gaps.

Uptown

The neighborhoods encompassed by the Uptown Planning District were diversely affected—the farther away from the river the more likely the flood damage. The natural levee of the Mississippi River provides a geological advantage, and the higher ground in the crescent that follows the river's curve is often referred to as the Sliver by the River or the Isle of Denial.

Late in the year many New Orleanians celebrated Christmas 2005 away from home, but a few residents constructed X-codes from Christmas lights (slide 4). Broadmoor is an Uptown area that did flood. In 2007 historic preservation students from University of North Carolina at Greensboro worked with the Broadmoor Community Center to document several affected historic buildings.

St. Bernard Parish

Just downriver from the Lower Ninth Ward, St. Bernard Parish is subject to the same types of natural and unnatural hazards. The MR GO and Intracoastal Waterway are just north of the parish's residential areas and these waterways funneled storm surge at such a rate that there were levee breaks as well as severe overtopping. Walls of water descended on the small-town and suburban landscape, resulting in devastating damage.

Two photographs in this slide show display a different X-code—a brilliant yellow placard with a red X, indicative of a St. Bernard Notice and Order of Involuntary Demolition. A photograph of a two-story home (slide 17) by Christina Bray shows the standard code next to the placard. A 2010 photograph (slide 22) by Dorothy Moye shows the placard as the only marking on a house scheduled for demolition. The owners of the home in Bray's photograph successfully appealed their notice.25Text of Involuntary Demolition notice: NOTICE & ORDER of INVOLUNTARY DEMOLITION Address: (handwritten) No repair, rehabilitation, reconstruction, or maintenance activity is apparent at this address. This Property appears to be abandoned! This structure has been identified as and declared by the St. Bernard Parish Government to be a public health and safety hazard and INVOLUNTARY DEMOLITION ORDERED. To object to INVOLUNTARY DEMOLITION the owner, or another person with proper legal interest in this property, must file a written appeal with the St. Bernard Parish Department of Community Development, #261 Judge Perez Drive, Chalmette, La. The written appeal must provide a plan for the start of or proof of actual repair, rehabilitation, or maintenance of this structure. Involuntary Demolition will be delayed only when an appeal is being considered and stopped only if appeal is granted. Date Posted: (Handwritten) Posted by: (handwritten) Other: (handwritten)

French Quarter

The French Quarter occupies the high ground of the city, with the natural levee of the Mississippi the obvious choice for the eighteenth century European settlers.

Under constant debate is the fate of the Iberville Projects, public housing adjacent to the French Quarter and the Central Business District.

Lower Ninth Ward, 2007–2010

By 2007 very little rebuilding had happened in the section of the Lower Ninth Ward most devastated by the levee break. Clearing of debris left vacant lots and front steps that led nowhere, while hundreds of deteriorating structures remained untouched. Handmade street signs were the norm, although floated houses blocking streets had been removed. Photographers visiting for the first time were shocked to see how much remained to be done. Those who had visited before could detect small differences, with activities of nonprofit and community groups the most visible.

In 2008 renovations were under way and changes were apparent in the Holy Cross section of the Lower Ninth. The flooding there had not been as devastating and more houses remained standing, though waiting for attention. X-code markings were fading, but still evident. Also in the fall of 2008 and early 2009 a major art invitational, Prospect.1, brought art installations and accompanying traffic into the Lower Ninth Ward. A conceptual installation by Berlin artist Katharina Grosse used an abandoned Holy Cross home as a canvas to depict an inferno with the house’s code untouched (slides 12 and 13).

In 2010, approaching the fifth anniversary of the storm, the Holy Cross neighborhood has benefitted more visibly from renovation and rebuilding than the other areas of the Lower Ninth. Clear signs of life contend with still significant numbers of slowly deteriorating structures. There are clusters of new homes near the largest levee break, including several spectacular structures from Brad Pitt's Make It Right project.

Lakeview, 2007–2010

From the bulldozed remains of old houses in Lakeview new ones have arisen, renovated homes have been elevated to meet insurance demands, and new levee walls are in place in one of the lowest spots in the New Orleans area. There are still gaps in the façade, with vacant lots as well as derelict and see-through buildings, but by the end of 2008 there were few X-codes to be found.

Before and After in Lakeview

Lauren Tilton illustrates the before and after of two 40th Street locations. The first photo, taken in November of 2005 shows houses whose float paths were blocked by a tree and a utility pole. The same location, shot in March, 2010, is a vacant lot.

Tilton also recorded the changes at 446 Spencer Avenue from 2006 to 2010.

Bywater, 2007–2010

The Bywater and Marigny neighborhoods are among the city’s most rapidly gentrifying. They also seem to be the locations that have preserved their codes most carefully. The codes are fading but, as noted by Chris Rose in a 2007 column, they are often displayed as “. . . badges of honor.”26Rose, op. cit.

Rose describes an art work by Erica Larkin who created a permanent provenance in wrought iron: “Farther down the block, at the corner of Montegut and Chartres, the glass sculptor Mitchell Gaudet's home is adorned with an iron replica of the existing glyph, superimposed over the original painted marking, a bold statement of intent to never let the memory fade away.”27Ibid. “One of the better examples of embracing the X for its symbolic meaning,” adds Richard Campanella.28Campanella, Richard. E-mail communication August 31, 2009.

Larkin created the duplicate code for Gaudet as a Christmas gift in 2005. She was shocked by the reaction of some neighbors who resented the reminder, but has since received commissions to replicate X-codes for other survivors.29Larkin, personal conversation, June 15, 2010.

Joel Lowy, of Washington, DC, recalls his 2008 photographs of the Bywater: “All photos were taken on a beautiful spring Sunday morning in May. . . Many of the marks were not painted over, despite both time and obvious new repairs. Each is a badge of courage to the emergency workers and residents. Reminiscent, for me, of the NY and DC response to 9/11.”

Before and After in Bywater

Two residents of the St. Roch neighborhood in front of a gutted house in 2006. The second image in 2010 shows the house now boarded up.

Joel Lowy and Dorothy Moye photographed the same location in Bywater almost two years apart. By 2010, it appears from the debris pile that restoration has begun.

Three Spaces Over Time

Repeat visits to three locations by several photographers reveal the progressions of three sites over the five years since Katrina.

The Mount Carmel Missionary Ministries at the corner of Forstall and Galvez Streets in the Lower Ninth Ward has attracted photographers since early post-Katrina. Stewart Harvey showed the sturdy brick building as a backdrop to demolished houses looking north on Forstall Street in February 2006 (slide 1). The Mount Carmel Missionary Ministries sign is visible still hanging above the front door. In March, Paul Conlan recorded the church’s hand-lettered sign asking, “Can these bones rise again?” next to the X-coded window (a stained glass Jesus).30Full text of the sign in front of Mount Carmel Missionary Ministries building: Restoration: Can these bones live? O ye dry bones hear the word of the Lord! Can these bones live? These bones shall live; and ye shall know that I am the Lord! So I prophesied. (Side) Lower 9th Ward. Ezekiel 37:1–7, Apostle Arthal Thomas He remarked on the chaotic interior, with jumbled furnishings attesting to the force of the water that swept through the building.

By January 2007 light filtered through colored glass windows on a starkly beautiful interior that had been gutted and cleaned. In 2008 the windows were boarded over and the X-code disappeared. The exterior signs remained, although their locations changed occasionally.

In June 2009 it was startling to see a new white paint job, with volunteers’ colorful handprints on windows and the door. The Jesus window now bore a smiley face. A year later the new paint job was beginning to weather, and the deteriorating sign still asked its question. The Mount Carmel Missionary Ministries sign had disappeared.

Board and Battered

Ian J. Cohn, a New Orleans native, has returned to the city repeatedly to assist in his family's recovery, each time photographing a house at 726 Lizardi Street in Holy Cross.

Canal Boulevard, Lakeview

A classic Art Deco-style home on Canal Boulevard in Lakeview demonstrates a progression toward renewal.

The front door displayed a textbook X-code, completely contained on the period door and marked with successive water lines. Christina Bray's photograph of the door in 2007 is such a good example that it has been licensed for use by HBO for the montage of images in the opening credit of the TV series Treme. The house sat untouched for almost another year, before being gutted, with the coded door in place. By February 2009, the sparkling white restoration was for sale with a new front door; the original door had disappeared. In June 2010 the house was a home, occupied and again a part of the street’s life.

Conclusion

The X-code has become by default a visual icon of post-Katrina New Orleans. Loved or hated, threatening or comforting, a source of survival pride or a negative mark to be obliterated, easily interpreted or enigmatic, a striking graphic or disrespectful graffiti, a major issue or a minor annoyance—all of these reactions persist. In 2010 the remaining markings, even those deliberately preserved, are severely fading and sometimes eroding into “ghost codes.”

These "ghost code" examples, with their distinctive fading pattern the result of some unknown chemistry, leave only a shadow of their original marks. This process of disappearance, as with the other gradually disappearing codes, is comparable to ways that pieces of the past slide into history and memory.

This online exhibition has noted varied reactions to the painted codes, as well as the unprecedented volume of the marks across the city. For more than ten years, search-and-rescue personnel have used the X-code system in many situations nationally, but never to the extent deployed in New Orleans. More recently, in response to complaints of after-effect damage of spray-painted messages on the housing stock, search-and-rescue workers have developed a new tool for marking—a fluorescent sticker to be applied to a door or window, conveying the same information as the painted X-code.31Crawford, Capt. Mike, Maryland Task Force One. E-mail correspondence and telephone conversation, April 20–21, 2009. In future disasters, search and rescue personnel will abandon the painted graphics used after Katrina, and proceed stocked with stacks of low-residue stickers and felt-tipped markers, their progress through the streets marked by a trail of fluorescent rectangles applied to the least damageable surfaces they can find. This practical and more manageable protocol for communication will no doubt have fewer side effects, but from a visual point of view, can never achieve the apocalyptic graphic impact seen in post-Katrina New Orleans.

The documentation of the X-code in New Orleans tells one small piece of the Katrina story. A straightforward reaction to the visual power of the coding has morphed into other stories yet to be fully developed—an examination of the impact of repetition on the visual experience, and the principles of expression underlying coded messages, to name only two. Photographs record the visual impact of repetition and the visceral power of the X, but they do not explain it. We are left to react, ponder, and interpret. The body of documentation leads us to consider the meaning of coding in everyday life. It demonstrates how in tragic circumstances markings that are inadvertently interpreted as symbols can haunt our memory, or how an official graphic repeated endlessly tells a story or morphs in our perception into found art. On one level, it celebrates heroism and memorializes lives. On other levels, the code continues to invite further investigation. On many levels, the X-code leaves us haunted and New Orleans unique.

About the Curator

Dorothy Moye is a Decatur art consultant and a former resident of New Orleans who has retained ties to and an ongoing fascination with the city. Her current project on post-Katrina search-and-rescue building markings is a response to the haunting visual impact of the thousands of these markings after the storm, many of which remain even five years later. Despite years of organizing exhibitions and other large-scale arts projects, Katrina + 5: An X-code Exhibition is Moye’s first virtual exhibition. A preliminary article on the project is at http://www.southernspaces.org/2009/x-codes-post-katrina-postscript. Moye holds membership in numerous arts organizations, both local and national. She graduated from UNC–Greensboro and North Carolina State University in Raleigh with degrees in sociology.

About the Photographers

Jane Fulton Alt, Evanston, Illinois. Fine art photographer and clinical social worker. Alt participated as a counselor with the Look and Leave program November 2005, accompanying Lower Ninth Ward residents on their first limited visits back to their homes. Her book, in which many of these photographs first appeared, is Look and Leave: Photographs and Stories From New Orleans's Lower Ninth Ward (Center for American Places at Columbia College Chicago, 2009). http://janefultonalt.com

Ellen Luckett Baker, Atlanta, Georgia. Author and owner of The Long Thread. Baker visited New Orleans for the first time in early 2008 and found the x-codes “end-of-the-world eerie.” http://thelongthread.com/

Christina Bray, Decatur, Georgia. Artist and youth minister. Bray has been traveling regularly to New Orleans since Katrina participating in the Episcopal Diocese of Louisiana’s Rebuild program in the city. http://christinabray.com/home.html

Richard Campanella, New Orleans, Louisiana. Geographer and author, assistant research professor, Department of Earth & Environmental Sciences, Tulane University. Campanella’s two most recent books, Geographies of New Orleans: Urban Fabric Before the Storm and Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans, illuminate the geographical and social difficulties as well as the rewards of life in a precariously sited urban area. http://tulane.edu/sse/eens/richard-campanella.cfm

Ian J. Cohn, New York, New York. Photographer, designer, and architect. Cohn is a native of New Orleans and states, “My intent in taking the pictures was both documentary as well as ‘artistic,’ but the documentary part is based on the concept that I was there to bear witness.” His blogs on returning visits to the city are insightful journals of days immediately post-Katrina. http://www.diversity-nyc.com/

Paul Conlan, Newnan, Georgia. Photographer, member of New Orleans Photo Alliance, Atlanta Photography Group, and and the Roswell Photographic Society. Conlan specializes in southern subjects. http://www.fstopblues.com/-/fstopblues/about.asp

Elyse Defoor, Atlanta, Georgia. Studio artist. Defoor has emotional ties to New Orleans and has responded to the post-Katrina experience with a multi-media exhibition titled X.U.ME. http://elysedefoor.com/

FEMA photographers: Jocelyn Augustino, Andrea Booher, Patricia Brach, Win Henderson, Patsy Lynch, Bob McMillan, Marvin Nauman, Alberto Pillot, and Liz Roll.

Collette Fournier, Spring Valley, New York. Photographer and member of Kaimonge Photography Collective. Fournier’s work is the result of a Kaimonge grant to cover post-Katrina events. http://www.kamoinge.com/collettevfournier.htm

Brian Gauvin, New Orleans, Louisiana. Photographer. Gauvin’s first post-Katrina images are among the earliest included in the exhibition and convey an on-the-scene immediacy.

Stewart Harvey, Portland, Oregon. Photographer. Harvey had begun a photography series on New Orleans in 2003, and on his first post-Katrina return he struggled to make sense of the visual chaos and devastation. His focus eventually became the character of the people who had survived this experience. http://www.stewartharveyphoto.com

Herbert H. Hill, Pullman, Washington. Chemistry professor, Washington State University. Hill reunited with old friends to work on a Rebuild project in New Orleans in 2009. http://analytical.chem.wsu.edu/faculty/hillh.

Constance Lewis, Atlanta, Georgia. Fine art photographer and gallery owner, independent curator. Lewis’s curatorial projects include the founding of Opal Gallery, an Atlanta based artist collective: and, exhibitions in Paris, San Francisco, and Atlanta. Her most recent book project, Oraien Catledge: Photographs (University Press of Mississippi) will be released this year.

R. Joel Lowy, Silver Spring, Maryland. Lowy is a biomedical researcher who knows what it’s like to miss New Orleans and enjoys calas, BBQ oysters, and funk.

Thomas Mann, New Orleans, Louisiana. Artist and gallery owner. Mann was able to gain early access to the city in order to stabilize his Magazine Street gallery. His exhibition Storm Cycle: An Artist Responds to Hurricane Katrina was created as an immediate response to the storm and has been traveling since 2005. http://www.thomasmann.com/

Gigi O’Shea, Decatur, Georgia. Elementary school teacher and New Orleans co-adventurer.

Liza Politi, New York, New York. Producer, actor, teacher and photographer. Politi photographed a series centering on the first anniversary of the storm. http://www.lizapoliti.com/

Megan Privett, Siler City, North Carolina. Privett was a graduate student in historic preservation at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro in 2007 and participated in a class project of digital documentation of four historic buildings in New Orleans. She now works as a historic preservation specialist.

Shari Seltzer, Westfield, New Jersey. Artist. Seltzer and her son visited New Orleans for the first time in early 2010 with a rebuilding group. They worked in the Lower Ninth Ward and the codes they saw as they traveled through reminded them of the Biblical story of Passover. http://web.archive.org/web/20100910022812/http://blogservices.net/ss/index.php

Cynthia Scott, New Orleans, Louisiana. Artist. Scott has photographed extensively in her Faubourg St. John neighborhood, and produced numerous installations and sculptures from post-Katrina debris. http://Cynthiascott2000.com

Kathy Shorr, New York, New York. Photographer. Shorr founded the Summer in the City Project, which brings adolescent girls from disadvantaged communities in New Orleans to New York for an experience in art, culture, and fun. http://www.kathyshorr.com/

Lynnell Thomas, New Orleans, Louisiana, and Boston, Massachusetts. Assistant Professor of American Studies at University of Massachusetts-Boston. Thomas identifies herself as part of the Katrina Diaspora, and her recent research focus is on the racial components of Louisiana tourism. Her New Orleans East subdivision website is http://web.archive.org/web/20100904030649/http://thekingswoodassociation.com/id4.html

Lauren Tilton, New Orleans, Louisiana and New Haven, Connecticut. Tilton has recently completed an assignment as Virtual Classroom Coordinator at the World War II Museum in New Orleans, and is a PhD student in American Studies at Yale University.

Tyler and Lane Turkle, Tallahassee, Florida. Artists. The father and daughter Turkles have been photographing in New Orleans since 2007. They see their collaborative work as useful in the recovery of the neighborhoods they document, and have returned several times to continue their series. Collectors of their New Orleans images purchase by way of a donation to the rebuilding program of their choice. http://www.tylerturkle.com/

Acknowledgments

The curator would like to thank those who have helped to bring this project to this stage. Special thanks to Allen Tullos, Frances Abbott, and the staff of Southern Spaces who have continued to believe in the value of this project; my family, especially Todd, Rachel, Will, and Sarah Moye who have always had the resources I needed at any given moment; Agnes Scott College intern Leslie Burhenn who assisted in organizing more than five hundred images; friends and colleagues who helped to visualize how to tell this story, including Tom Mann, Amy Landesberg, Rob Amberg, Judith Schonbak, and the twenty-five photographers who are a part of this exhibition; Elaine and John Clements who have never failed to say, “Welcome Home,” when I arrived in the city to enjoy their unfailing hospitality; and the amazing and inspiring people of New Orleans who have been showing me how to keep it real for most of my life.

Publication Update

In the spring and summer of 2018, Southern Spaces updated this publication as part of the journal's redesign and migration to Drupal 7. Updates include image, slideshow, and text link adjustments, as well as revised recommended resources and related publications. For access to the original layout, paste this publication's url into the Internet Archive: Wayback Machine and view any version of the piece that predates March 2018.

Recommended Resources

Text

Alt, Jane Fulton. Look and Leave: Photographs and Stories from New Orleans’s Lower Ninth Ward. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2009.

Antoine, Rebecca, ed. Voices Rising: Stories from the Katrina Narrative Project. New Orleans, LA: University of New Orleans Press, 2008.

Brinkley, Douglas. The Great Deluge: Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans, and the Mississippi Gulf Coast. New York: Harper Perennial, 2006.

Campanella, Richard. Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans. Lafayette: University of Louisiana Press, 2008.

Horne, Jed. Breach of Faith: Hurricane Katrina and the Near Death of a Great American City. New York: Random House, 2006.

Maklansky, Steven, ed. Katrina Exposed: A Photographic Reckoning. New Orleans, LA: New Orleans Museum of Art, 2006.

Piazza, Tom. Why New Orleans Matters. New York: Regan Books, 2005.

Polidori, Robert and Jeff L. Rosenheim. Robert Polidori: After the Flood. Göttingen, Germany: Steidl, 2006.

Rose, Chris. 1 Dead in Attic: After Katrina. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007.

Web

“From the Graphics Archive: Mapping Katrina and Its Aftermath.” New York Times, August 25, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/08/25/us/mapping-katrina-and-aftermath.html.

Hurricane Digital Memory Bank. Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, George Mason University (Fairfax County, Virginia). 2005–2017.

http://hurricanearchive.org.

The New Orleans Index. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, August 29, 2011.

https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-new-orleans-index.

Romaguera, Christopher. “Spray-Painted FEMA X Still Marks the Storm in New Orleans.” Curbed. August 19, 2015. https://www.curbed.com/2015/8/19/9929170/fema-x.

Spitzer, Nick. "This Is Not My Beautiful House: Act Four: The Long Way Home." This American Life, Episode 297. September 16, 2005.

https://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/297/this-is-not-my-beautiful-house.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Codrescu, Andrei, cover blurb for Jane Fulton Alt, Look and Leave: Photographs and Stories from New Orleans’s Lower Ninth Ward. Center for American Places at Columbia College Chicago, 2009. |

|---|---|

| 2. | http://hurricanearchive.org/. The Hurricane Digital Memory Bank uses electronic media to collect, preserve, and present the stories and digital record of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. George Mason University’s Center for History and New Media and the University of New Orleans, in partnership with the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History and other partners, organized this project. |

| 3. | Perlstein, Michael, “For Tales of Life and Death, the Writing’s on the Walls,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, September 17, 2005, p.1. |

| 4. | Barton, Frederick. E-mail correspondence, November 24–25, 2008. |

| 5. | Defoor, Elyse. E-mail correspondence, May 8, 2008. |

| 6. | Rose, Chris. "Badges of honor: Part historic preservation, part act of defiance, the spray-painted markings of Katrina rescue workers remain prominently displayed on many reoccupied New Orleans homes." New Orleans Times-Picayune, July 24, 2007. |

| 7. | Spitzer, Nick. E-mail correspondence, June 16, 2009. |

| 8. | Piazza, Tom. Why New Orleans Matters, New York: Regan Books, 2005, 125. |

| 9. | Smith, Barbara Lee. E-mail correspondence, September 15, 2009. |

| 10. | Perlstein, loc.cit. |

| 11. | Baker, Ellen. E-mail correspondence, August 27, 2009. |

| 12. | These are words and phrases that cropped up repeatedly in varied conversations. |

| 13. | Mann, Thomas. Storm Cycle: An Artist Responds to Hurricane Katrina. Bellevue, Washington: Bellevue Art Museum, 2006, 7. |

| 14. | http://www.fema.gov/, Urban Search and Rescue (US&R) Response System Field Operations Guide, FEMA, September 2003 (US&R-2-FG), p. 56. |

| 15. | Ibid., p. 54 |

| 16. | Thomas, Robert A. E-mail correspondence, June 22, 2010. |

| 17. | Ryan, Thomas M. LTC (ret). E-mail correspondence, June 27, 2010. |

| 18. | Sydenstricker, Capt. L. Paula, 153rd Mobile Public Affairs Detachment, "West Virginia National Guard Plays Vital Role in the Infantry Mission," Defense Video & Imagery Distribution System (dvids), http://www.dvidshub.net/news/3054/west-virginia-national-guard-plays-vital-role-infantry-mission, September 19, 2005 |

| 19. | Brinkley, Douglas, The Great Deluge: Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans, and the Mississippi Gulf Coast. New York: Harper Perennial, 2007. (First published 2006, William Morrow.) |

| 20. | Barton, loc. cit. |

| 21. | All images marked "FEMA News Photo" are works of a Federal Emergency Management Agency employee, taken or made during the course of an employee's official duties. As works of the US federal government, all FEMA images are in the public domain. |

| 22. | Campanella, Richard. E-mail correspondence, February 2, 2010. |

| 23. | Louisiana French spelling. Alternates forms: voudun, vodou, voodoo. |

| 24. | Saint-Lot, Marie-Jose Alcide. Vodou, a Sacred Theatre: The African Heritage in Haiti. Coconut Creek, Florida: Educa Vision, 2003, 105. |

| 25. | Text of Involuntary Demolition notice: NOTICE & ORDER of INVOLUNTARY DEMOLITION Address: (handwritten) No repair, rehabilitation, reconstruction, or maintenance activity is apparent at this address. This Property appears to be abandoned! This structure has been identified as and declared by the St. Bernard Parish Government to be a public health and safety hazard and INVOLUNTARY DEMOLITION ORDERED. To object to INVOLUNTARY DEMOLITION the owner, or another person with proper legal interest in this property, must file a written appeal with the St. Bernard Parish Department of Community Development, #261 Judge Perez Drive, Chalmette, La. The written appeal must provide a plan for the start of or proof of actual repair, rehabilitation, or maintenance of this structure. Involuntary Demolition will be delayed only when an appeal is being considered and stopped only if appeal is granted. Date Posted: (Handwritten) Posted by: (handwritten) Other: (handwritten) |

| 26. | Rose, op. cit. |

| 27. | Ibid. |

| 28. | Campanella, Richard. E-mail communication August 31, 2009. |

| 29. | Larkin, personal conversation, June 15, 2010. |

| 30. | Full text of the sign in front of Mount Carmel Missionary Ministries building: Restoration: Can these bones live? O ye dry bones hear the word of the Lord! Can these bones live? These bones shall live; and ye shall know that I am the Lord! So I prophesied. (Side) Lower 9th Ward. Ezekiel 37:1–7, Apostle Arthal Thomas |

| 31. | Crawford, Capt. Mike, Maryland Task Force One. E-mail correspondence and telephone conversation, April 20–21, 2009. |