Overview

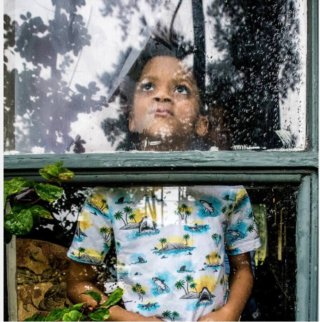

In a series of thirty-three photographs taken in North Carolina and Mississippi, Tom Rankin evokes two years of everyday, extraordinary "Covid weather," affirming through images the fullness of wonders and contradictions close to home.

We can all remember when the Covid reality fully hit, that moment when we were forced to confront the stark news and the hard arrival of abrupt change. I remember exactly where I was standing when it all sunk in. I was photographing in Mississippi in early March 2020, on spring break from teaching at Duke, my near annual pilgrimage to get back to making pictures. I had been washing my hands incessantly as I drove from North Carolina to Mississippi, always keeping sanitizer close, trying to puzzle out how to respond to the invisible, infectious threats, and how to stay safe and productive. Like so many photographers, I was trying to make images of the visible and invisible viral effects of this unknown storm. Mostly photographing outside, I worked to try to understand and accept this gathering mystery. An email arrived announcing that spring break would be extended another week, all Duke classes would move on line, and with that began a collective retreat into the virtual and isolated refuge of distance. We would stay at six feet and farther, adapt and adjust, do whatever needed to be done.

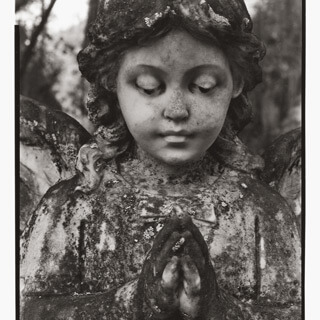

There are no truly universal feelings about the shared experience of Covid, but there is, I believe, a collective impression that we’ve all experienced a tangle of time, a displacement from the normal markers and seasons, a confronting of the inequities that accompany a pandemic, a fuller view of vulnerability and mortality. Amidst the diversity of ways we’ve managed the many interruptions and anxieties, the unknowing and the seeming to know, there’s shared understanding of a narrowing and shortening of our movements, maps, and itineraries. Through it all I’ve photographed. Sometimes in direct response to covid—with a sense that there’s something rare and exceptional about the moment—and at other times just doing what I always do.

I’ve come to understand that any photograph made during Covid is a ‘Covid photograph.’ To be sure, I recognize that some images made over the last couple of years are directly observing a response to Covid. Images of health care workers, vaccine researchers, shuttered businesses and empty offices, empty stands at athletic events, all of those and more are deeply identified with the pandemic. But so are all the other images, photographs made with full recognition of our altered routines and attitudes, the lightness and darkness that we observe having shifted. There is no way to separate the act of making pictures from a recognition of the injuries caused by the weather that surrounds. The Covid weather tightened our geography, led to a perspective that sees closer and perhaps with more intimacy, intended or not. Anytime we find ourselves looking at a singular sameness, we hope for deeper clarity and precision of sight. If there is hopefulness here, it is in the realization that there’s forever more to see in the most ordinary; another way to compose, to transform the world into an image, to confront the temporal luminance before us in an otherwise dimming day.

There is a recognizable evil tyranny in assuming that our worlds never fall apart, in taking the day-to-day for granted. We like to think we know better (“Here today, gone tomorrow,” and all that). Whatever we know doesn’t prevent us from the familiar condition that when at home the protagonist so often wishes to be away, and when away the deepest wish is often to be at home. Making pictures throughout Covid has been energized by an acceptance of a shrinking physical daily terrain, of being isolated in smaller places. My reply was to busy myself by affirming through images the fullness of wonders and contradictions close to home.

Photographers—and photographs—get all they have from embracing the darkness and light equally, shadows adjacent to highlights, contrast next to flatness, what is present alongside what has gone, low fertile valleys juxtaposed with the dry peaks. The opposites are coequal and mutually dependent, elemental to how we see. The last line from Psalms 139:12 is “the darkness and the light are both alike to you.” Alike, I argue, in that both arrive daily, and perpetually offer us a frontier to explore, render, and move to reveal, a time and place to take full visual advantage of the mystery and the uknown.

About the Author

Tom Rankin is Professor of the Practice of Art and Documentary Studies at Duke University where he directs the MFA in Experimental and Documentary Arts. For fifteen years he was director of the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke. His books include Sacred Space: Photographs from the Mississippi Delta (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1993); Deaf Maggie Lee Sayre: Photographs of a River Life (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1995); Local Heroes Changing America: Indivisible (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2000); One Place: Paul Kwilecki and Four Decades of Photographs from Decatur County, Georgia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013); and Goat Light (Durham, NC: Horse and Buggy Press, 2021) coauthored with Jill McCorkle. His photographs have been collected and published widely and included in numerous exhibitions. A frequent writer and lecturer on photography, culture, and the documentary tradition, he is the general editor of the Series on Documentary Arts and Culture with the University of North Carolina Press.

Public Health in the US and Global South is a collection of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications examining the relationship between public health and specific geographies—both real and imagined—in and across the US and Global South. These essays raise questions about the origin, replication, and entrenchment of health disparities; the ways that race and gender shape and are shaped by health policy; and the inseparable connection between health justice and health advocacy.

Beginning in 2022, the series expands to include 1000-word blog posts, as well as longer commentaries, essays, articles and media productions that address the public health and political implications of the COVID-19 pandemic from multiple viewpoints. The series editor for Public Health in the US and Global South is Mary E. Frederickson.