Overview

In Drifting into Darien: A Personal and Natural History of the Altamaha River, Janisse Ray provides an ecological and personal account of the largest river in Georgia. In this excerpt, Ray tells the story of James Holland, a crabber from Darien, Georgia, and founding member of the environmental organization Altamaha Riverkeeper. Nancy Marshall's photographs accompany Ray's text.

"James Holland, Riverkeeper: Environmental Protection along the Altamaha" was selected for the 2011 Southern Spaces series "Landscapes and Ecologies of the US South," a collection of innovative, interdisciplinary publication about natural and built environments.

Essay

|

| Nancy Marshall, Moon over Darien River, Georgia, 2010. |

I have a story about a crab that started a movement. It is about a river that is stunning in its magnitude and in its biodiversity. It is about a man who turned his tenacious mind and undistracted gaze upon that body of water and decided that he would clean it up, and who, in the process, became somebody he never dreamed of being. The story is about the creation of a group of advocates in a part of the United States that had not known environmental advocacy, and a litany of successes that built an environmental ethic and caused this deeply beloved sedimentary river to run cleaner out of Georgia, into the sea.

The story is one of the transformation that is possible if one wakes up to the beauty and wonder of the earth, if one fears not, if one follows the path of his or her heart. The story of the transformation possible if people join together and decide to protect something they love. With love, many things are possible.

In a boat at the mouth of the Altamaha River sat James Holland, around him the sea boiling, an eight-foot tide meeting thousands of gallons of fresh water minute by minute. The air was diaphanous with salty mist, like a veil. A finger of white sand reached out from Little St. Simons Island as if to calm the waters, and on that arm of firmament crowded ruddy turnstones, yellowlegs, oystercatchers, and willets.

Below, in the calmness and silence of the gray depths, a male blue crab carried his girl. She had molted and they had mated and for forty-eight hours he was carrying her, right-side-up and forward, and when her shell hardened he would release her, and she would begin her migration back into the salt, beautiful swimmer, with a cargo of two million eggs.

Many of which, for some reason, would not survive.

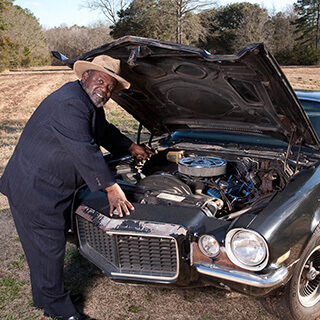

|

| Nancy Marshall, James Holland, Altamaha River, Georgia, 2010. |

The boat carried Holland, like the river water carries nutrients to feed the plankton. Like the ocean carries salt. Holland was working these waters, motoring in his old boat from float to float he recognized so well. Every trip was a connect-the-dots; he hauled up the traps and took from them the crabs he was allowed to take, returning the rest to forage through the delta mud.

The numbers in the coolers spoke: they were falling, 300 pounds, 225, 175. Every year they fell—he remembers 1,500 pounds easily from one hundred traps in a day.

When Holland got hungry, he cut the engine and rested on the waters, dolphins in the foreground, pelicans diving headfirst, waves tapping the craft in a kind of SOS. "Do you see what is happening?" they were saying in their insistent language. The sky ever changed. The estuary stretched from the river, its bed a channel, a tablet upon which the water records what is happening to Georgia, from the first bubbles of spring water in the piedmont, to the confluence, to the fanned-out delta. On the other side of Holland lay the wide and faltering ocean.

Holland had no idea that his life was about to change permanently and that for the rest of his days he would become a voice for wild places and wild things. In a way this was a natural progression. Holland had been a warrior before, a marine, and he knew how to fight.

Like the spark of life the female blue crab carries in her orange sponge, an idea began in him. The voice of the voiceless spoke, and sitting in the rocking boat, eating a tuna sandwich, drinking warm coffee, he began to listen. Willet, willet, willet, the voice said. To watch it simply vanish is a sin against God.

Get up, James, the voice said. The sun is already high in the sky. Stand up.

You are a big man, you are strong, you have two hands capable of doing anything. You have a great mind. I have given you eyes to see and ears to hear. But I have given you something more, James, something special. What I have given you is a heart big enough to care, with room enough to love even the blue crab, which every day you hold in your big hands and admire.

When he reached land and stood up, the ground trembled.

In the 1940s, a little boy who did not understand much of what was happening in his world retreated to a creek near Cochran, Georgia, to sail leaf boats, to build dams, to swim, and to fish. That was James Holland. He will not talk much about what happened to this little boy, because some of it he would rather forget. The river was with him from the start.

|

| Nancy Marshall, Altamaha River, Georgia, 2010. |

Years later, after a career in the Marines and another in food services, after a family was mostly raised and gone, after twenty-five years in a boat in the hot sun, healing from all that had happened, laboring to forget, drawing up traps, worrying some about money, he came home to the river that knew him when he was a boy, lost and found. The river found him, and then he returned and found it.

First there was a language to learn that had not been his own. It was not "sook," not "gas line," not "Doboy Sound," not "robust redhorse." This new language had long, scientific, technical, academic, political words, and lots of initials. DNR, EPD, PSP, OVC, SMZ, MOA, BMP. He had to learn it all, he who had never had a chance to go to college, who had known nothing except hard work all his life.

By God, he would understand what the people who had the river by the throat were saying. He learned more than he ever thought possible. He could have been a biologist. He could have been a lawyer. He could have been a writer. He could have been a public official.

But James Holland was needed on the ground, on the water. He was needed in public meetings, standing in front of the people.

Poor people live up and down this river. We work for years to buy a johnboat. Some of us are badly educated, even ignorant. We throw car tires and deer carcasses in the creeks. We dump trash and other bad stuff in. We cut down trees.

But if we could understand a car engine, we could understand a river system, and for it to run it needs all its parts, and the parts have to be clean, in good working order, and they need fuel.

We needed to know how to translate all this.

Industry takes advantage of our ignorance, our silence, our consuming worries. It takes the fish, it takes the forests, it dumps copper and arsenic into the water, it erects coal plants that fill the air with mercury that drifts down into the river. It tries to build poultry processing plants, it schemes waste incinerators and biomass plants.

In a poor region of the country, with a citizenry poorly educated about the environment, the river's time had come. Altamaha Riverkeeper was born, and Holland became the first actual, official Riverkeeper. Membership grew exponentially. The years passed and Holland traveled through the watershed, ferreting out lawlessness, ringing the bells of the people supposed to be regulating and protecting the watershed. There was a lawsuit, another lawsuit, another lawsuit. The federal judges were sympathetic to the law.

I've seen lots of activists at work and I've never seen anybody mobilize people the way Holland did. Maybe it's that he's clear about what he wants and he demands it. One thing I've noticed: he makes a lot of phone calls. Even when he could do a task alone with less effort, he takes time to involve people on many levels. He reaches out to people through their established friends. He worries with a problem until he has an idea. He finds someone who can help him. He asks for help. If he's told no, he asks again or finds someone else.

At 8:30 one Sunday morning many years ago, for example, my phone rang. "Were you sleeping?" Holland boomed.

|

| Nancy Marshall, Big Cypress, Altamaha River, Georgia, 2010. |

"No," I said. "I was lying in bed, reading."

"I was laying in bed at 4:00 a.m. this morning, waiting until I could get to work," he said. "You're crabbing today?"

"Yep," he said. "Heading out now. But listen, I have a favor. I just talked to my first cousin. Her husband is a professor in Athens. Which shows that all my folks didn't turn out like me. She'll get our press release to the university newspaper. I want you to mail it to her."

"Ok," I said, and jotted down the address.

"And include a short note," said Holland, "to let my cousin know that a human being sent it."

A lot got done in ten years. Holland was out front, but behind him was Deborah Sheppard, the staunch and steady executive director who had left an Atlanta activist career to live on the coast, writing grants and press releases and doing the thankless work of keeping the whole ship afloat. She filled in Holland's gaps. She backed him up. They were a dynamic duo.

After a few years I began to notice something. In addition to the photos of destruction that Holland would send by e-mail, copying everybody he thought might help on every travesty, he began to e-mail pictures of beautiful things, wild things, rare things, endangered things: tiger swallowtail butterflies, wood storks constructing nests, raccoons washing food, water hyacinth, gulf frittillaries, sparring bucks, roseate spoonbills, sunning alligators, four wood ducklings on a log. As the years passed, the photos became more beautiful and more numerous. In the end, I think, the travesty was too much even for Holland's calm, rational, Marine-trained mind, too much for his immensely capacious heart. He couldn't keep focusing on tragedies.

"Even when I was seeing the degradation, I saw that beauty was still there," he said. "I found out that the most beautiful flowers on God's earth are around wetlands."

After ten years, Holland retired. On his last official day on the job, in May of 2010, he called to tell me that the City of Jesup was dumping raw sewage again, the mess visible around the pipe, stringing in the trees. There were more condoms than you can believe, he said. Every year they do it, he said. We talk to them and talk to them and they keep doing it.

|

| Nancy Marshall, Altamaha River, Georgia, 2010. |

For his retirement, people came from up and down the river, from within the watershed and without, to honor him, and to thank him. They came from Tattnall County, Appling County, Wayne County, Toombs, Jeff Davis, McIntosh, Telfair. They came from Atlanta, Savannah, Macon, Athens. They thanked him for being a champion of rivers, conqueror of polluters and destroyers, defender of wild things, campaigner for justice.

"What you gave us was hope," I told him. "You made us want to fight. You were a warrior and you were fighting and we fell in step beside you. You inspired us. You performed miracles in front of our eyes."

From Holland I learned that transformation is possible. Watching him was watching the monarch emerge from her cocoon and take off over the tips of the milkweed.

Holland gave the Altamaha River a fighting chance. He gave it and its people the greatest gift a person could give, life itself, through eleven years of ceaseless labor and unflinching dedication to a grand corner of creation that is the Altamaha watershed.

Holland was the first Riverkeeper. But not the last. He simply started it all. It is a movement that is unstoppable.

Success is hard to measure. But I believe that water quality in the basin has improved steadily, incrementally, one part per million at a time, since Altamaha Riverkeeper lodged like a grain of sand in a clam and grew to become a pearl.

About the Author

Janisse Ray was born in Baxley, Georgia in 1962 and graduated from the M.F.A. program at the University of Montana in 1997. She currently resides in the Altamaha Community of Reidsville, Georgia and teaches in the MFA program at Chatham University. She has published poetry and non-fiction books, including Ecology of a Cracker Childhood (1999).The excerpt "James Holland, Riverkeeper: Environmental Protection along the Altamaha" comes from Janisse Ray's Drifting into Darien: A Personal and Natural History of the Altamaha River (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011).

About the Photographer

Nancy Marshall is a native Atlantan now living in McClellanville, South Carolina. She received her M.F.A. in Photography from Georgia State University School of Art and Design in 1996. Her work is widely exhibited and collected. Marshall's awards include the National Endowment for the Arts/Nexus Grant for Book Arts, a Southern Arts Foundation Fellowship for Photography, an Emory College Excellence in Teaching Award for the Humanities, and a fellowship with the Ossabaw Island Genesis Project.

Recommended Resources

Cerulean, Susan, Janisse Ray and Laura Newton, eds. Between Two Rivers: Stories from the Red Hills to the Gulf. Tallahassee, FL: Heart of the Earth, 2004.

McGregor, Jerrilyn. Wiregrass Country. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1997.

Morrison, Carlton. Running the River: Poleboats, Steamboats & Timber Rafts on the Altamaha, Ocmulgee, Oconee & Ohoopee. St. Simons Island, GA: Saltmarsh Press, 2003.

Murphy, Reg. "The Easy Ways of the Altamaha." National Geographic, January 1998.

Ray, Janisse."Waiting for the Tide: Creating an Environmental Community in Georgia." Orion Afield, Summer 1999.

———. Ecology of a Cracker Childhood. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 1999.

———. Wild Card Quilt: The Ecology of Home. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2004.

———. Pinhook: Finding Wholeness in a Fragmented Land. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2005.

———. A House of Branches. Nicholasville, KY: Wind Publications, 2010.

———. Drifting into Darien: A Personal and Natural History of the Altamaha River. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011.

Rogers, George A. and R. Frank Saunders, Jr. Swamp Water and Wiregrass: Historical Sketches of Coastal Georgia. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1984.

Links

Altamaha Historic Scenic Byway, Georgia Department of Transportation

http://www.dot.ga.gov/travelingingeorgia/scenicroutes/Pages/default.aspx.

Altamaha Riverkeeper

http://www.altamahariverkeeper.org/index.asp.

Altamaha River Partnership

http://www.altamahariver.org/.

Center for a Sustainable Coast

http://www.sustainablecoast.org/.

Conserve Water Georgia

http://www.conservewatergeorgia.net/.

Environmental Education Alliance (EEA)

http://www.eealliance.org/.

Georgia Department of Natural Resources

http://www.gadnr.org/.

Georgia Info, Georgia Digital Library

http://georgiainfo.galileo.usg.edu/altamahariver.htm.

Georgia River Network

http://www.garivers.org/other-georgia-rivers/altamaha-river.html.

Lower Altamaha Historical Society

http://www.loweraltamahahistoricalsociety.org/index.php.

The Nature Conservancy

http://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/regions/northamerica/unitedstates/georgia/placesweprotect/georgia-altamaha-river.xml.