Overview

In this photo essay set in mining communities of southern West Virginia and eastern Kentucky, Earl Dotter seeks out changes in consumption and leisure, healthcare, coal mining practices, and the environment that have occurred since he first photographed in the region in 1968. The lives of Dotter's Appalachian subjects and the impact of the coal industry on landscapes continue to be central themes in his work. All photographs taken by Earl Dotter from 2005–2006.

"Coalfield Generations" is part of the 2008 Southern Spaces series "Space, Place, and Appalachia," a collection of publications exploring Appalachian geographies through multimedia presentations.

Introduction

Taking pictures in conjunction with Volunteers In Service To America (1968-1970), then continuing with Miners for Democracy and the United Mine Workers Journal, Earl Dotter was one of the first to document miners' fights for better healthcare, pensions, working and living conditions. As his work expanded to the textile and fishing industries, Dotter maintained an emphasis on the multi-faceted, dangerous, and detrimental conditions facing rank-and-file workers and their families. In the photo essay featured here, Dotter continues his attention to miners, having photographed some individuals, such as black lung pioneer Dr. Donald Rasmussen, for decades, and families, such as the Hipshires of Logan County, West Virginia, for generations.

"Coalfield Generations: Health, Mining, and the Environment" presents images taken in 2005 and 2006 during Dotter's trips to towns in eastern Kentucky and southern West Virginia. He documents transformations in the mining industry, including health and safety initiatives and technological changes. Selected images from this essay have appeared in two exhibitions at Wheeling Jesuit University: "The Genesis of Downtown: Logan-Welch West Virginia Urban Coalfield Life, The Photographs of Russell Lee and Earl Dotter, 1946 and 2006" and "Our Future in Retrospect: Coal Miner Health in Appalachia."

"Coalfield Generations" provides new images, organizing them around themes that Dotter has explored for three decades: Town Life, Health Issues and Healthcare, Working at the Mines, and Mining and the Environment. The accompanying commentary from a 2008 interview with Southern Spaces provides insight into his work.

Downtown Logan apartment dwellers. Logan, WV, 2006.

In Town Life, Dotter photographs residents in eastern Kentucky and southern West Virginia as they go about daily lives and leisure pursuits. He visits a local swimming pool, a baseball field, family gardens, a supermarket, and a Wal-Mart built on a strip mine bench, using each setting to highlight the ways in which commerce and consumption are transforming the mountain landscape.

Health Issues and Healthcare acknowledges the prevalence of chronic disease in the region, including black lung, but also such illnesses as heart problems, diabetes, and hypertension. Dotter distinguishes generational differences in miners' healthcare: retired and actively-working miners have benefit plans with affordable access to local care, while many working-age coalminers have been laid off, leaving them with few, if any, healthcare options.

Working at the Mines sketches the contemporary coal industry and life in the mines. While technological advances have made work safer, Dotter records the aftermath of catastrophes, such as the 2006 Sago Mine disaster. His images of laid-off and out-of-work miners suggest current tensions between miners and coal company management.

Mining and the Environment delves into surface mining processes and their impact on Appalachia's mountains, waterways, and landscapes. Heavy coal trucks and erosion damage the region's roadways, contributing to dangerous driving conditions and automobile fatalities. Dotter also finds a new generation of volunteers coming to the region to test water quality and assess the environmental costs of industrial mining.

Town Life

Connecting with people in specific places lies at the heart of Dotter's project of documenting miners. The photographs in this section sample daily life in the coalfields, from family reunions and baseball parks to changing patterns of consumption and town structures. Through his photographs of the everyday, Dotter challenges stereotypes of Appalachia while calling attention to contemporary problems.

Changes in the coal industry have affected the area in myriad ways, some of them depicted in these images. While coal keeps the lights on, businesses like Wal-Mart are becoming the major employers. When mines close and the number of miners decreases, company housing may deteriorate, be abandoned, or replaced by mobile homes. But this is not just a story of desolation: homes remain, with hanging plants and wind chimes. A consistent element of Dotter's work locates his subjects' effects on their communities despite difficult conditions.

Dotter's work chronicles other concerns in these coalfield towns, particularly problems of health — obesity, tobacco use, and disability. Due to automobile accidents, work-related accidents, and substance abuse, disability rates are high here. Working conditions, unemployment rates, and poor roads also take their tolls.

Many of Dotter's photographs of daily life tell stories of consumption, particularly the ubiquity of tobacco and the epidemic of obesity. Sugar-laced soda is a constant in this area as demonstrated by the women on their porch, the boy at the baseball game, the man in the grocery store, and the RC sign that announces Whitesburg, Kentucky. Other photos in this series feature outdoor pursuits such as gardening and fishing. In the captions below, Dotter speaks about some of these images.

Earl Dotter

Employment: Wal-Mart has become West Virginia's largest employer. That's a pretty surprising statistic in light of the impact the coal economy has had on West Virginia for generations. That this Wal-Mart is situated on a strip mine bench underscores the irony. Jobs that used to be in the mines are moving to corporate big box stores like Wal-Mart.

Community: Downtowns that used to be a hub of community life in the coalfields are also impacted in a major way by the movement of commerce to national chains and big box stores. You see adjacent to the Wal-Mart a Holiday Inn Express. We've all probably stayed in that kind of hotel, but back in the days when I was a shooter for the United Mine Workers Journal, I would stay in the Pioneer Hotel in downtown Logan, which supported the downtown of that county seat town.

Consumption: It's a fact that throughout our society, families often need two wage earners. If one adult in a family setting would be largely responsible for the garden, someone also needed to take a job at Wal-Mart or a local fast food restaurant at a minimum wage to support a modest lifestyle. There's a wave of diabetes throughout the coalfields that relates to the food consumption habits of coal mining families. In following shoppers at the local supermarket, I saw heavy emphasis on prepackaged food, on soda pop, and items low in food value. That's a difference that's glaring.

Diet and obesity: My conception of an Appalachian individual when I first came to the coalfields during the war on poverty was a lean, gaunt, skinny individual. Today obesity is a major issue in the coalfields. Lifestyle changes, even the mechanization of work, have altered the physique and the health of mining folks that I rub shoulders with. Diet plays an important role. Used to be most folks had garden plots outside their homes in these company towns, but that's almost history. The older generation still puts them out, but not so much the current working population.

Changes in housing structures: My photos of buildings are emblematic of the change that's occurred from the days when I regularly stumbled upon intact coal camps in the 1970s. That was at the end of an era. Today I return to Dehue, West Virginia, just outside the county seat of Logan in Logan County, and find just a bare field with a prep plant being built on that site. Where I can, I show the old and the new in juxtaposition — in McRoberts there's the newer mobile home, trailer, against the falling-down row of old camp houses with the mountain in the background. That picture is useful in showing the difference.

Health Issues and Healthcare

This sequence of photographs begins in Appalachian clinics, highlighting the emblematic mining disease black lung, as well as the rise of diabetes. Healthcare, its quality and access, has changed thanks to the work of people like Dr. Donald Rasmussen; however, health problems still trouble coalfield communities. There is a physician shortage and patients often have to travel considerable distances on poor roads to reach healthcare providers. Lack of adequate insurance also impedes disease prevention and treatment, particularly as the coal industry restructures, laying off younger workers and leaving them and their families without medical coverage.

Chronic and rapidly increasing rates of obesity-related diseases, as illustrated in the first pictures in this series, are the result of changing working conditions, lifestyle choices, and consumption patterns.

Although black lung is not as prevalent as it was twenty years ago, the remaining pictures in this series attest to its persistence among miners. Dr. Rasmussen, pictured administering care and in his office, has worked with miners since the 1960s, collaborated with lawmakers on legislation for black lung compensation. The final two pictures evoke earlier generations of black lung through the remembrance of two miners' fathers.

Problems associated with older generations of miners, such as a lack of healthcare providers, under-nutrition, inadequate medical benefits, and black lung treatment, have improved; however, new diseases, particularly those relating to consumption and to changing working conditions, are causing new problems. In his 2008 interview with Southern Spaces (excerpted below), Dotter discusses some images and issues in more detail.

Earl Dotter

Changes in healthcare: The whole healthcare system has changed to a great extent. The miners who are actively working continue to have a fairly useful health benefit plan that provides them with healthcare and with medications. They have local providers, their own physicians, or their primary care facilities in their communities to access. What's different is there are so many coalminers of working age who have been laid off and left high and dry and whose health benefits soon disappear. I profiled a local UMWA worker who was so impacted in Kanawha County, West Virginia. There were coalminers in their fifties and late forties who had lost their jobs at a mine where they had worked for fifteen or eighteen years, just short of retirement and of being eligible for lifetime healthcare. One miner had lost his house and was sleeping in the local union hall. I followed him to a free clinic in Clay County, some distance away, where he was getting medication for hypertension, heart problems, and early-onset diabetes.

Healthcare also becomes a major issue when coal companies purchase facilities, shut down the operations, lay off the miners, then reopen under new corporate settings. These new companies do not rehire the miners who were active under the previous contract. Instead of hiring the local workers who have worked in a mine for generations, the new management will employ workers who drive fifty, sixty miles from adjacent counties to work in that facility. That's a strategy that plays on the fact that miners are not all working from the same community that was adjacent to the mines.

Generations of miners: This project was an opportunity for me to reconnect with the next generation of coalminers that I had worked with back in my days with the UMW Journal. The cover of my book, The Quiet Sickness featured the photograph of Lee Hipshire, a deep miner who had died of black lung at the age of fifty-seven. I had met several of his sons at the time I photographed Lee. This exhibit gave me the opportunity to look up his sons who were still working in the coalmines. I found Lee Hipshire, Jr., and another brother who was working at the mountaintop removal site in Boone County. I was able to profile their family life some forty years since my initial coverage with the Mine Workers Journal.

Distance and healthcare: One of the problems that leads to severe cases of illness is the distance residents have to travel to healthcare facilities. Because it's a high cost item to have to travel these days from a remote location to a health care facility, health problems tend to get addressed later rather than sooner in the coalfields. This leads to higher rates of cancer, diabetes, and other chronic diseases.

Pioneer black lung doctor, Donald R. Rasmussen says, "The disease continues to be a problem at smaller mines in the region." Beckley, WV, 2005.

On Dr. Donald Rasmussen: To the extent you have a network within the coalfields, you can open doors that would not ordinarily be available. I knew Doc Rasmussen back in 1978 and he appreciated the work that I did in that era when I was active in not only helping miners but also advocating improvements in state and federal mining dust laws and compensation law. He appreciated the fact that I was returning three decades later to resume my documentation of his work with black lung victims.

Working at the Mines

In the 1970s, Dotter worked in the coalfields as a photographer for the United Mine Workers Journal. In these photographs, he returns to the working lives of miners. Particularly, he documents changes that have occurred since his earlier engagement with these communities. In the first four images, he outlines contemporary economic, technological, and organizational factors that have altered the face of mining in Appalachia. Symbolized by shuttered union halls with poignant graffiti, the decline of UMWA membership undermines worker control over relations with coal companies. Such control is necessary to combat the changing dynamics of power in the labor force. Coal companies employ legal strategies, such as bankruptcy reorganization, to trim down their labor forces and replace career miners with new ones. Many career miners find themselves without jobs and without the pensions and benefits they worked a lifetime to earn. Although the UMWA has taken some measures to fight these company strategies in court, its dwindling numbers render such struggles difficult.

Another factor hurting union membership is the general downsizing of the labor force with the advent of new surface mining technologies that replace a large mining workforce with a smaller group of machine operators. In the Appalachian region, surface mining technologies for mountaintop removal impact the economy most profoundly. Dotter captures these shifts in technology that have diminished the labor force in a series of images about miners in Boone County, West Virginia. The small group of miners posed with their dragline bucket suggests the impact of mountaintop removal technologies. Later images of individuals operating and repairing machinery testify to the decreased number of working miners.

Dotter's images of new technologies also illustrate the advances in mine safety. In his photograph of the miner operating a roof bolting machine, he points out improvements that allow miners more support in the mine and less proximity to coal dust agents. These are step towards healthier working environments. Yet, these advances have not eliminated mining tragedies, such as the 2006 Sago Mine disaster, and their tragic consequences for miners and their families. Through images of disaster hearings, Dotter documents these human losses. Below, Dotter discusses changes in working at the mines.

Earl Dotter

Technological advances in mining: One of the things that is quite different is the fact that there are fewer workers in a mine today than when I first went underground in 1973. I see longwall mining operations, and one worker is at the shear — a football field length long machine that traverses the coal face shearing off the coal. There's just one individual and all that coal is spilling onto an automated belt. That's different. Roof-bolting is a much, much more secure job than it used to be because of these machines that hydraulically support the roof where the roof-bolt is being inserted, so the miners are much better protected than they used to be. The continuous mining operator operates the machine with a remote control device further back from the face so he's much less at risk from roof falls as well as from respirable dust. Those are just a few examples.

Mining disasters: My picture-taking strategy is to include family members, spouses, and younger children in the tragic settings because they are devastated by these events. I feel that viewers of the photographs have a better way of relating to the loss when they see other family members included in the scene. For instance, the pictures of the family members at the Sago Mine Disaster hearing in 2006 holding pictures of their lost father and showing the grief that overwhelms them. I feel that these photographs should be seen by individuals outside of the community because I want them to have ways to identify with the tragedy.

Miners' livelihoods: This photo shows the mine-worker community expressing the stress at their livelihood being at risk, and all that represents — healthcare, a decent income, housing. The backdrop is a house that this miner had acquired. It was designed by a program of Yale architects to provide affordable and substantial rebuilt housing for coal field residents in Cumberland, Kentucky. While this miner was still active and working, he was expressing concern about his neighbors' losing their jobs and their homes.

The UMWA: The shuttered union hall is symptomatic of the decline of unionized coal mining in Appalachia. It is under siege. The mine workers union, in its entirety of active miners, is the size of a large local of the Teamsters — around forty thousand today. That's ten percent of what it was when I was first involved with the reform movement in the 1970s. So the shuttered local union hall is a profound symbol for the decline of the UMWA. Its viability is mostly in its retirement protections and the health benefits it offer retirees. Significant political support continues those protections, but active miners who are members of UMWA are far fewer today.

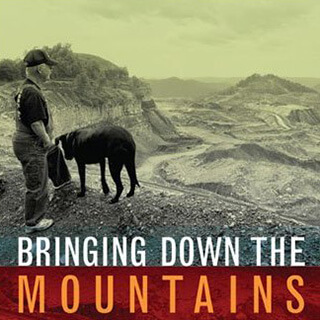

Mining and the Environment

In this series of photographs about the impact of new surface mining techniques on the environment, Dotter captures the threat that mountaintop removal strip mining poses to the natural environment, residents and their communities, and constructed features such as roadways. Initial images portray the mountaintop removal process in progress, as miners operating dragline shovels remove the overburden covering a coal seam on a mountaintop in Boone County, West Virginia. A vertical shot captures the devastation of the natural skyline and the proximity of the ecosystem's upheaval to a nearby residential community in McRoberts, Kentucky. Dotter's images follow the process of coal extraction and removal as trucks haul mined coal from mountaintop sites and deposit it on rail cars and barges leaving the region. The proximity of these operations to waterways highlights questions about water pollution at sites like the Kanawha Coal Load Out Facility in Montgomery, West Virginia.

Another group of images depicts valley fill waste impoundments, where coal companies dump refuse from mountaintop removal and coal extraction. Dotter's images capture the shroud of privacy in which such sites exist with warning signs, as well as the ways in which coal sludge and other waste erode land and water. Such impoundments threaten towns with waste disaster devastation (as happened in Martin County, Kentucky in 2000) because of the sheer volume of refuse dumped there. New generations of environmentalists protest these conditions in the Appalachians. Dotter highlights these activists in images of Raleigh County, West Virginia, home of the Brushy Fork Sludge Impoundment — more than seven billion gallons of coal slurry sitting precariously above schools and homes.

Dotter reveals the damage that large machine coal operation exacts on the built environment through images of roads destroyed by the constant traffic of treacherously overloaded coal trucks. Coupled with an endemic disregard for seatbelt use in the region, these unsafe routes contribute to traffic accidents and dangerous travel conditions. Dotter talks about the contemporary impact of mining on the environment in excerpts from the 2008 interview, below.

Earl Dotter

Mountaintop removal: Of course, strip mining goes back to the 1950s in Appalachia on a much smaller scale. But with the emergence of larger machinery and the mountaintop removal technique, the impact is hard to miss today. Communities where there is no coal are spared and remain with their beautiful mountaintop skyline, but it's not hard to find that skyline interrupted dramatically when you go to a hollow that has several seams of coal that have been accessed by removing the overburden and moving that overburden into the only available location in the hollows that are adjacent to that mountaintop. That has impacted runoff and created dramatic incidents such as occurred in Martin County, Kentucky eight years ago and other communities that you hear about on a smaller scale. I worry that we'll have another hundred-year storm like the Buffalo Creek flood and the impact of that will be quite severe because of what has occurred with mountaintop removal.

Dangerous roads: Fifteen percent of adults in McDowell County are disabled and I think that relates to a number of situations: dangerous workplaces, dangerous highways, risky lifestyle at various ages. You travel secondary roads and you see these memorials put up by family survivors of accidents where relatives have lost their lives on a hairpin turn. You see overloaded coal trucks plowing head-on into cars with families inside, and you see individuals who are intoxicated behind the wheel. There are problems that need to be addressed with healthy eating and healthy living.

Activism: This new generation of environmental activists came from all over the United States—mostly the eastern United States—but there were kids from New England, from the South, and they were working with a local activist who was concerned, most specifically, with a school built under a very significant mine-waste impoundment — and a very large coal silo built almost immediately behind this school. These activists had scientific backgrounds and were doing tests of water quality in the area. They had other expertise that they were sharing with locals. It's not too different from my era when VISTA and Appalachia volunteers were on the scene providing specific expertise and assistance when requested.

Acknowledgements

Frances Abbott, Katie Rawson, and Sarah Toton contributed the written portions of this piece.

About the Photographer

Since 1968, Earl Dotter has photographed miners in Appalachia. Trained at the School of Visual Arts (1967-1968), Dotter became interested in photography, publishing his early work in New York magazine. In 1968, he joined VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America), working with miners and their families in Cookville, Tennessee. In 1972, Dotter became a staffer of the mine-reform newspaper, The Miner's Voice, before photographing for the United Mine Workers of America's United Mine Workers (UMW) Journal. Dotter documented miners' health and safety conditions as well as the changing aspects of miners' lives. Leaving the UMW Journal in 1977, he continued to photograph the Appalachian coalfields, as well as Carolina textile towns and other sites of hazardous work, producing his 1996 exhibit, "The Quiet Sickness: A Photographic Chronicle of Hazardous Work in America," and a 1999 exhibit, "Appalachian Chronicle, 1969-1999: The Photographs of Earl Dotter." Dotter has won numerous awards for photojournalism and contributions to the labor movement.

Recommended Resources

Text

Abramson, Rudy. "Mountaintop Removal: Necessity or Nightmare?" Now and Then: The Appalachian Magazine 18 (Winter 2001): 20–24.

Amberg, Rob. "'Photographs of Lasting Value': An Interview with Earl Dotter." Southern Quarterly 34.1 (Fall 1995).

Baldwin, Fred D. "Access to Care: Overcoming the Rural Physician Shortage." Appalachia: Journal of the Appalachian Regional Commission 32 (May–August 1999): 8–15.

Barnett, Elizabeth et al. Heart Disease in Appalachia: An Atlas of County Economic Conditions, Mortality, and Medical Care Resources. Morgantown, WV: Prevention Research Center, West Virginia University, 1998.

Barry, Joyce. "Mountaineers Are Always Free? An Examination of the Effects of Mountaintop Removal in West Virginia." Women’s Studies Quarterly 29 (Spring/Summer 2001): 116–130.

Bauer, William M, and Bruce Growick. "Rehabilitation Counseling in Appalachian America." Journal of Rehabilitation 69.3 (2003): 18-24.

Bell, Fred and Laurance J. Donnelly. Mining and its Impact on the Environment. New York: Routledge, 2006.

Burns, Shirley Stewart. Bringing Down the Mountains: The Impact of Mountaintop Removal on Southern West Virginia Communities. Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University Press, 2007.

Casto, James E. "Rx for the Rural Health-Care Shortage." Appalachia: Journal of the Appalachian Regional Commission 29 (September–December 1996): 22–27.

Derickson, Alan. "The Role of the United Mine Workers in the Prevention of Work-Related Respiratory Disease, 1890-1968." In The United Mine Workers of America: A Model of Industrial Solidarity?, edited by J. Laslett. 224–238. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996.

Dotter, Earl. The Quiet Sickness: A Photographic Chronicle of Hazardous Work in America. American Industrial Hygiene Association, 1998.

Ellis, Betty. A Comprehensive Bibliography of Health Care in Appalachia. Lexington, KY: Appalachian Center of the University of Kentucky, 1988.

Fox, Maier B. "Afterword: Prospects for the UMWA." In The United Mine Workers of America: A Model of Industrial Solidarity?, edited by J. Laslett. 545–554. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996.

Freese, Barbara. Coal: A Human History. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing, 2003.

Gaventa, John. Power and Powerlessness: Quiescence and Rebellion in an Appalachian Valley. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1980.

Gaventa, John, Barbara Ellen Smith, and Alex Willingham. Communities in Economic Crisis: Appalachia and the South. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990.

Johnnsen, Kristin, Bobbie Ann Mason, and Mary Ann Taylor-Hall. Missing Mountains: We Went to the Mountaintop but It Wasn't There. Nicholasville, KY: Wind Publications, 2005.

Montrie, Chad. To Save the Land and People: A History of Opposition to Surface Coal Mining in Appalachia. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Mulcahy, Richard. "A New Deal for Coal Miners: The UMWA Welfare and Retirement Fund and the Reorganization of Health Care in Appalachia." Journal of Appalachian Studies 2 (Spring 1996): 29–52.

———"Power of Illness & the Promise of Health in Appalachia." Now and Then: The Appalachian Magazine 17 (Spring 2000).

Rasmussen, Donald L. "Black Lung in Southern Appalachia." The American Journal of Nursing 70.3 (1970).

Reece, Erik. Lost Mountain: A Year in the Vanishing Wilderness. New York: Riverhead Books, 2006.

Stewart, Kathleen. A Space on the Side of the Road: Cultural Poetics in an "Other" America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996.

Witt, Matt. Photographs by Earl Dotter. In Our Blood: Four Coal-Mining Families. New Market, TN: Highlander Research and Education Center, 1979.

Web

Amberg, Rob and Earl Dotter. "The Engaged Observer." Southern Changes 17.2 (1995).

http://southernchanges.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/sc17-2_1204/sc17-2_003/.

“Bringing Down the Mountains.” West Virginia Highlands Conservancy

http://www.wvhighlands.org/Pages/BDTM.htm.

"Coal, Industry, Labor, Railroads, Transportation." Appalachian Studies Bibliography, 1994–2004.

http://www.libraries.wvu.edu/bibliography/coal.htm.

“Coal Mining.” Environmental Literacy Council.

http://www.enviroliteracy.org/article.php/1122.html.

Film

Harlan County, USA. 1976 dir. Barbara Kopple.

Justice in the Coalfields. 1995 dir. Anne Lewis.

To Save the Land and People. 1999 dir. Anne Lewis.