Overview

Elliott J. Gorn reviews Darryl Mace's In Remembrance of Emmett Till: Regional Stories and Media Responses to the Black Freedom Struggle (University of Kentucky Press, 2014).

Review

|

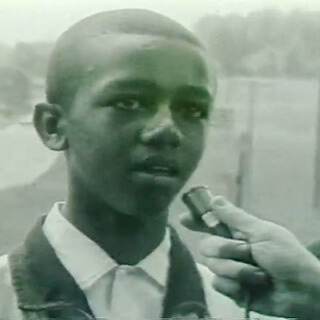

Emmett Till continues to torment our imaginations. How could two (and almost certainly more) grown men, veterans, over six feet tall, see a fourteen year old kid as such a threat to "the southern way of life" that they tortured and killed him? How could a Mississippi court exonerate them? The story haunts us still, and more important, it haunted a whole generation of people, especially those who became activists in the Freedom Struggle.

Darryl Mace's In Remembrance of Emmett Till: Regional Stories and Media Responses to the Black Freedom Struggle is the latest installment in the growing shelf of books about the Till murder and its aftermath. (Truth in reviewing: I'm at work on a book about Till too.) Mace's book is by turns useful, clear, thoughtful, and frustrating.

Mace argues that the murder of this Chicago youth—who whistled at a white woman at a crossroads grocery store in Money, Mississippi, in August 1955 and was lynched for it—catalyzed men and women into an irresistible movement for change. He's right; so many people roughly of Till's age when he was murdered look back at his death and the acquittal of his killers as a formative moment in their lives, from Anne Moody to Muhammad Ali, from Stokely Carmichael to Congressman John Lewis. Mace is not the first to suggest this, but the point bears repeating.

In Remembrance of Emmett Till is structured around newspaper and magazine coverage of the murder, funeral, trial, and their aftermath. More precisely, Mace argues that there were significant differences in how print media covered the events based on section of the country—Midwest, Northeast, Southeast, and West Coast. He also gives plenty of space to African American journalism, sometimes folded into his geographical schema (the Chicago Defender is a midwestern publication, the California Eagle a western one), but sometimes, more appropriately, as a category of its own.

Mace's sectional differences are significant, but perhaps overblown. After all, few newspapers sent reporters to Mississippi. Most simply edited and reprinted wire service stories, then added a comment on the opinion page and a letter to the editor or two. So it is a little striking that Mace generalizes, for example, that "readers in Seattle and Denver were somewhat sympathetic to the Till family, while readers in San Francisco were largely disinterested in the Till case" (124). His footnotes cite one letter each from the sympathetic towns, none from the disinterested one. Or again, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette published two very pointed letters to the editor after the "not guilty" verdict, which leads Mace to conclude, "Such letters made it clear that most people were tired of business as usual when it came to cases of racial violence" (105). From two letters?

|  |  |

| Coverage of the Emmett Till trial in Jet, September 22, October 6, and October 13, 1955. | ||

There are further problems with inferring sectional opinion from newsprint. First, as Mace's own evidence shows, the tone of newspaper coverage changed depending what part of the story was being covered. For example, northeastern print media largely ignored Till's murder, but once the trial began, gave harsh condemnation of the South and its people and institutions. Such subtlety often gets lost. Worse, Mace too easily picks up the moralistic tone of some editorialists' condemnations of the white South in which all are hopelessly benighted and racist. It is certainly true that even liberal editors like Greenville's Hodding Carter circled his wagon with the others against northerners' assaults on his adopted state, especially those coming from deeply segregated towns like Chicago and New York. But at his least cautious, Mace questions whether any sincere anger or regret about Till's murder could issue from an area of the country so steeped in racism.

What is so tragic about the Till story is not that southerners were uniformly hateful or at least indifferent. Outrage followed the initial reports of the murder. But outrage soon gave way to caution and sectional defensiveness. The tragedy of the story comes from the fact that people like Hodding Carter knew better, were truly horrified by the viciousness of the crime, but were not so horrified that they failed to defend Mississippi's honor. More important, they soon downplayed the viciousness of Till's killing to defend "the southern way of life," which is to say segregation. They loved justice, but when push came to shove, they loved segregation—or more precisely, they feared integration—more.

So Mace is right that Till's killing blurred nuances between liberals and conservatives. But that needs to be explained, not explained away. For example, Mace is so determined to show a thoroughly racist South that it is impossible for him to credit the prosecutors with anything but bad faith. He isn't wrong about the racism—read the trial transcript and it's clear that lead prosecutor Gerald Chatham couches his case in classic racial paternalism. But most participants, such as James Hicks who covered the trial for several African American newspapers, Murray Kempton of the New York Post, and even Emmett's mom Mamie Till-Mobley, praised the prosecutors. The attorneys were rushed (the trial took place three weeks after the murder), had inadequate resources, made mistakes, but clearly they wanted convictions, and wanted them badly. Why did they not ask for the death penalty? Because they knew that no white jury would send the defendants to their deaths. They argued the case with the very opposite of indifference, with unmistakable passion. The trial judge too, Curtis Swango, was mostly quite fair, according to contemporary accounts, black and white, northern and southern.

That fairness is part of the tragedy too. Good intentions were beside the point. Observing proper judicial forms didn't matter. Twelve white men simply would not convict someone of their ilk of murdering an African American, especially when most of the evidence came from blacks themselves. The Till trial was a classic example of institutional racism. Feelings of good will or fairness or paternal generosity were useless; the outcome was all but preordained in a political and legal system built up over generations.

There are other problems with In Remembrance of Emmett Till. Sometimes Mace is downright sloppy with details. For example he describes J. W. Milam shooting Emmett Till in the back of the head (133). Milam did shoot Till, but just above the ear, as Mace reveals elsewhere. Or, Mace describes Clenora Hudson-Weem's 1994 Emmett Till: Sacrificial Lamb of the Civil Rights Movement as the book that "resurrected" the study of the case (136), but he fails to mention (or even to list in his biography) Stephen J. Whitfield's 1988 book A Death in the Delta: The Story of Emmett Till.1Cleonora Hudson-Weems, Emmett Till: Sacrificial Lamb of the Civil Rights Movement (Boston: Bedford, 1994); Stephen J. Whitfield, A Death in the Delta: The Story of Emmett Till (New York: The Free Press, 1988). Mace also repeats Mamie Till-Mobley's belief that Emmett didn't whistle at Carolyn Bryant (148). Emmett stuttered, and whistling was a trick he sometimes used to break through his impediment. But those who were in the store, Till's cousins, have been clear and consistent through the years that what they heard was a wolf-whistle.

Sometimes the problems with In Remembrance of Emmett Till go beyond details. For example, two books preceded Mace's on the subject of newspaper coverage: Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff's Pulitzer Prize winning The Race Beat, and Davis W. Houck and Matthew A. Grindy's Emmett Till and the Mississippi Press.2Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff, The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006); Davis W. Houck and Matthew A. Grindy, Emmett Till and the Mississippi Press (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2008). Mace notes the former in passing and gives the latter no attention, even in his bibliography. This is important because both books explicate the vagaries of news reporting by race and place. Or again, Mace describes Carolyn Bryant's testimony before the court—Till, she said, asked her for a date, grabbed her hand, put his arm around her waist, used a word so obscene she couldn't repeat it, and finally let out his famous wolf-whistle. Mace of course is right that Bryant's claims were highly suspect, that even if everything she said was true it was no excuse for murder, and that most newspaper coverage was quite uncritical of her. But he ought to tell us too that the prosecutors vigorously objected to the jury hearing Carolyn Bryant, arguing that whatever took place in Money, Mississippi, on Wednesday had no legal bearing on a kidnapping and murder four days later. Judge Swango agreed, and he refused to let the jury hear her testimony. And that too didn't matter in the final verdict.

In Remembrance of Emmett Till adds to our knowledge of that terrible lynching and its aftermath. The author gives us fresh insight into the relationship between media, race, and the justice system. He reminds us just how important the Till murder and trial were for the future of the Freedom Struggle. If the book isn't always as precise as it might be, Mace still helps keep this story alive in all of its horror.

About the Author

Elliott J. Gorn is the Joseph Gagliano Professor of American Urban History at Loyola University Chicago. His books and articles embrace multiple aspects of urban and American culture, particularly the history of various social groups in American cities since 1800.

Recommended Resources

Text

Henderson, Carol E., ed. America and the Black Body: Identity Politics in Print and Visual Culture. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2009.

Houck, Davis W., and Matthew A. Grindy. Emmett Till and the Mississippi Press. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2008.

Hudson-Weems, Clenora. Emmett Till: Sacrificial Lamb of the Civil Rights Movement. Boston: Bedford, 1994.

Metress, Christopher. The Lynching of Emmett Till: A Documentary Narrative. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2002.

Pollack, Harriet, and Christopher Metress, editors. Emmett Till in Literary Memory and Imagination. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2008.

Roberts, Gene, and Hank Klibanoff. The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation. New York: Knopf, 2006.

Till-Mobley, Mamie, and Chris Benson. Death of Innocence: The Story of the Hate Crime That Changed America. New York: Random House, 2003.

Whitfield, Stephen J., and Thomas H. Wirth. A Death in the Delta: The Story of Emmett Till. New York: Free Press, 1988.

Web

Curry, Connie. "Son Ham's Hat." Southern Changes 15, no. 2 (1992), 15-17.

http://southernchanges.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/sc14-2_1204/sc14-2_004/?keyword=Son%20Ham%27s%20Hat.

"The Murder of Emmett Till," American Experience, Public Broadcasting Service. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/till/.

"The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till: New Documentary Uncovers Evidence in 1955 Murder," Democracy Now, June 15, 2005. http://www.democracynow.org/2005/6/15/the_untold_story_of_emmett_louis.

"Civil Rights: The Emmett Till Case." Eisenhower Presidential Library, Museum and Boyhood Home, Abilene, Kansas. Presidential Libraries System, National Archives and Records Administration. http://www.eisenhower.archives.gov/research/online_documents/ civil_rights_emmett_till_case.html.

Video

Nelson, Stanley. American Experience: The Murder Of Emmett Till, Documentary, WGBH Educational Foundation, Boston, 2003. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1-X4is9jMYk.

Beauchamp, Keith. The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till, Documentary, Velocity/Think Film, 2006.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bvijYSJtkQk.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Cleonora Hudson-Weems, Emmett Till: Sacrificial Lamb of the Civil Rights Movement (Boston: Bedford, 1994); Stephen J. Whitfield, A Death in the Delta: The Story of Emmett Till (New York: The Free Press, 1988). |

|---|---|

| 2. | Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff, The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006); Davis W. Houck and Matthew A. Grindy, Emmett Till and the Mississippi Press (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2008). |