Overview

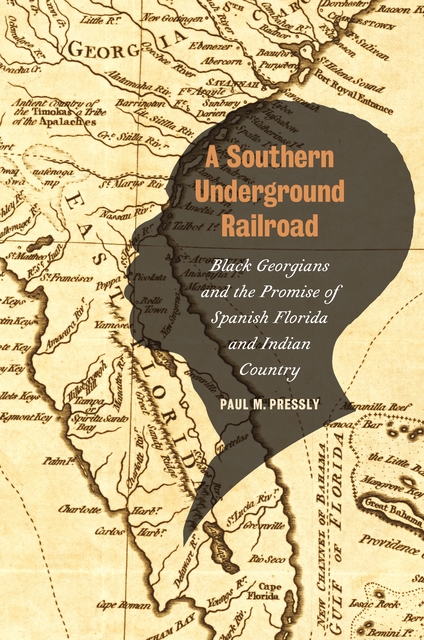

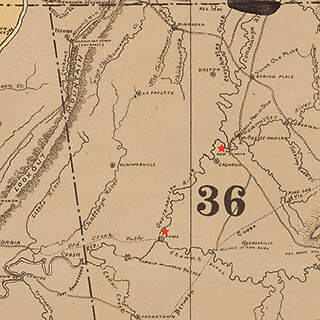

Thomas Hallock reviews Paul M. Pressly's A Southern Underground Railroad: Black Georgians and the Promise of Spanish Florida and Indian Country. (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2024). This book in UGA's Early American Places series is available in print formats, ebook, and via open access in a Manifold edition. For the benefit of readers, Hallock's review provides links directly to particular chapters, maps, and illustrations of the Manifold online book.

Prospect Bluff is one of the more remote historic sites you may ever visit. Perched upon the banks of Florida's Apalachicola River, the old fort is roughly an hour by car from Tallahassee. To get there, drive due west from the Florida capital, down Highway 20. Hang a left at SR65, south towards the Gulf, passing Dollar General towns like Telogia, Wilma, and Sumatra. Cross endless rows of slash pine, and rare red cockaded woodpecker habitat, then make a right at Gadsden Road. Technically the site is closed. Hurricanes shut down the federally protected landmark in 2023, and a gate blocks the dirt road that leads to the fort, though you can walk the remainder. Bring insect repellant. Any discomfort is rewarded by sylvan beauty and the sheer significance of the place. Here, during the long freedom struggle, self-emancipated Blacks organized as a semi-autonomous society, forging community in the piney woods by a stunning blackwater river, joining the British military in the wake of the combined 1812/Creek War. They met opposition, of course. Anxious to stop the flow of enslaved people from the southern borderland, Andrew Jackson ordered Edmund Pendleton Gaines to attack. In 1816, a hot cannonball struck the magazine, not too far from the Apalachicola, and the wooden fort went down in flames. Many of the survivors died, while others stole back into Florida's swampy frontier.

The attack on Prospect Bluff holds center stage in the ninth and final chapter of Paul M. Pressly's impressive study, A Southern Underground Railroad, a heroic effort to recover the nuances of a rich yet impossibly complicated subject — the "southern underground railroad" of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Florida. Former director of the Ossabaw Island Education Alliance, on coastal Georgia, Pressly understandably starts his study from the Atlantic barrier islands. While Gullah-Geechee people have long been cast as archetypes of preservation, as isolates holding African traditions alive, Pressly emphasizes mobility and freedom, telling a story of routes rather than roots. People of African descent, held captive in Georgia, worked through networks of communication and navigated braided channels of freedom across the St. Mary's River. Pressly teases out stories that largely occurred off-record, against the tangled status of liminal and contested landscape. A Southern Underground Railroad, in short, undertakes an extremely difficult task: to recover the stories of people who left a sparse written archive, from sources kept by those who sought to suppress them, from a milieu that typically falls outside the standard historiographic narrative of the early republic.

You have to work to get to this place. Whether academically or physically, we must actively recover the centrality of early Black Florida — because we know the stories are out there, even as the history hides in plain sight. All too often, scholars defer to default citation of Jane Landers, Black Society in Spanish Florida (1999), acknowledging past research without pushing the narrative forward. Others might recognize Kenneth W. Porter or Canter Brown, Jr. But the "southern" or "saltwater" underground railroad has never been secret. Joshua Giddings chronicled the Black roots of the Seminole War in his overlooked classic, The Exiles of Florida (1858), while Albery Allson Whitman twinned the two themes in an underappreciated epic, The Rape of Florida (1885). As early as the 1560s, with the founding of St. Augustine, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés would partly justify the invasion la Florida as halting a means to the flight of enslaved Caribbean people here. So why the gaps? Stories of self-emancipated people reach us today from the edges of the historical record, overshadowed by a nationalist narrative in the US, and almost always coming from the documentation left by enslavers and oppressors — not by those who found freedom themselves. These stories must be sought out.

Pressly's exceptionally well researched study works largely from examples. He begins in 1781, with nine individuals on a dock at Ossabaw Island. Led by an expert seaman known as Hercules, the nine freedom-seekers sailed one-hundred miles south to St. Augustine, where they found protection under the British military. Pressly pieces together this story from notices in the Georgia Royal Gazette. By situating a single granular case against broader trends, then alongside corroborating scholarship from elsewhere, Pressly completes a patchwork recovery. The remainder of the book moves chronologically, from the mid-eighteenth century to the Seminole War, when the United States' invasion of a weakened Spanish Florida brought a close to this still-overlooked "underground railroad."

Pressly sets up a tale of two cities, Savannah and St. Augustine, separated by the mazy floodplain of the St. Mary's River. He emphasizes that in negotiating their southern path to freedom, individuals and groups asserted their liberty both apart from white intervention and with full knowledge of broader political movements. "Far from passive individuals," Pressly writes, "they were well aware of the geopolitical landscape, and the enslaved people were ready to seize the moment when the time seemed ripe to make a break for the freedom offered by Spanish Florida to fugitives from British colonies" (12). In chapter two, "The Journeys of Mahomet," Pressly uses the life of an African-born and (presumably) Muslim individual of that name "as a measure of the type of man" (35) who chose maroonage, as well as the "noteworthy presence of women" in a flight that "underscores their determination and courage" (47). Pressly returns to the example of Hercules, who "offers a map for navigating the full spectrum of the landscape for Black people in revolutionary Savannah" (54). Hercules faced any number of options during the Revolutionary conflict, though amidst the disruption, he and other Black fugitives laid the groundwork that would provide freedom for decades to come.

"Entangled Borders" revisits the colonial boundary line of the St. Mary's River during Florida's second Spanish period (1783-1821), when "East Florida and southern Georgia evolved into one large zone of transition," in which "weak central authority" opened the space for "fugitives to find a path forward toward a new life" (76-77). Those escaping bondage often did so in groups, led by a skilled waterman over international boundaries, and the effort required careful planning and fortitude. The Spanish crown had long granted a modicum of rights to free Blacks, and the draw of a more liberated and permeable Florida generated anxiety in what is now the southern United States. Pressly’s chapter, "A Maroon in the Revolutionary South," recounts the "exploits of a man named Titus," whose choices "illuminate several faces of maroonage on the Georgia and Florida coasts and the fluidity of the borders" between them (94). These choices were exceedingly complicated; Titus was a "dancer" (102), having fled Georgia's Ossabaw Island yet remaining close to family and on the fringes of the plantation. His story illustrates a central theme of A Southern Underground Railroad: freedom amidst connection, runaways who were "connected with the realities of the Atlantic world" (111). This should come as no surprise, yet it bears restating: maroonage was complex.

These complexities are visible in the careers of two white men who thrived along the boundaries — John (or Juan) McQueen and William Augustus Bowles. Son of a Charleston merchant, schooled in England, and returning to South Carolina as a sea captain, McQueen swapped sides as economic needs suited him; in 1791, he emigrated to Florida and declared allegiance to Catholic Spain, taking 280 enslaved people with him. An even more bizarre episode involved William Augustus Bowles, a Loyalist who schemed to establish an Indian-British State of Muskogee. The conditions for boundary crossing lead Pressly to one of the more vexing problems of the book, the status of free Blacks among Native people.

In these intercultural cases especially, readers of a certain age may find in Pressly's monograph a southern version of Richard White's Middle Ground (1991). As with White's Ohio Valley, new and provisional identities were forged on an unstable borderland, where no single imperial power held control; on a still-contested frontier, individuals acted upon surprising possibility — then, in the decades after the War of 1812, the middle ground closed. A Southern Underground Railroad draws out the impossibly complicated intersections between chattel slavery and Native American life. After the Revolution, Creek conceptions of slavery shifted from kinship to commodification. Who, then, was a war captive and who was a slave? When Native people attacked a plantation, on which side would captive Blacks fight? Responses varied. Many Black Georgians "were horrified at the thought" of entering "a new form of slavery" among the Creeks (139); yet where most "Black people resisted capture," others "saw the arrival of warriors as an opportunity to break out of their oppressive condition" (140, 141). This historical landscape defies pat explanations. Drawing from an archive that is decidedly committed to perpetrators, Pressly unpacks stories still "wrapped in mystery" (145), reconstructing negotiations that escaped not only "the most determined [white] planters" (149), but no doubt the historian himself! An achievement of this book is threading a coherent narrative from this documentary labyrinth.

Pressly turns the study further south, to Florida, where Black Georgians saw "their best hope for securing freedom" among Seminole "migrants who trickled in from different spaces and for different reasons" (156). In defining the relationship between Black and Native life, Pressly must concede to an historiographic aporia: the impossibility of generalizing any one kind of relation, particularly from documentary evidence left mostly by whites. Would people of African descent on the Florida frontier be classified as freedom seekers, Black Seminoles, or as maroons? Scholars have "puzzled over" what terms to use (158), and the years from 1803 to 1812 especially, defined by a "diversity of conditions," must be understood with a "delicate balance" (175).

This "distinctly unsettled moment" (180) comes to a close with the US war against the Seminoles, the conflict that brings Pressly to Prospect Bluff. The book’s final chapter reviews the beginnings of this four-decade conflict (roughly, 1812 to 1858). Among the many stories, Pressly traces the fate of freedom seekers (or Black Seminoles, or maroons — any one term is not fully correct) from the Florida Panhandle, to encampments along the Suwannee River, to the "Angola" colony along Tampa Bay. Pressly’s brief Conclusion traces the closing of this southern middle ground, noting that while "the taming of a troublesome borderland for white Southerners was far from complete," the "outcome [was] no longer in doubt." (205). This four-page ending to a such a remarkably detailed study signals something of a disappointment. A Southern Underground Railroad collects case studies, rarely diving into methodology in any overt way, and as the book's short closing note reveals, Pressly rarely points to methodological concerns.

Coming at it from the perspective of a literary critic, and not a historian, I found this book about sandy Florida to be a bit theory-poor. The Conclusion belies that weakness. Keeping within an entrenched narrative, Pressly explains how the Southeast "offers a vital link" between Black Emancipation and the American Revolution. The story of Black Floridians "marks the passing of the torch of liberty from the generation of the Revolution to those who belonged to the era of the Underground Railroad, a grand connecting arc that stretches over a forty-year period" (208).

But I would have liked a stronger takeaway. The default to a national narrative feels unsatisfying precisely because conventional methodologies and storylines fail to cohere. The first problem is evidentiary. How does one reconstruct events from escaped people, while relying upon documents by their captors? What other source materials can one consider — oral traditions, art, non-sequential histories? Or, if the documentary record leaves the historian bereft, why not lean into speculation? Pressly's more satisfying moments are when he settles on "puzzling." And lastly, where does a study such as this one lead us today? Following a far more visible trail of print sources, historians of slavery rightly trace a storyline from national liberty to a literature of social reform to Emancipation. But as Langston Hughes wrote, in different context: "I wonder if it's that simple." When, in the United States, will we let the margins define the center? As we remain a nation prone to sliding backwards, where past gains have proven to be far from definitive, would it not be far more effective to take the half-steps, ambiguities, and blended allegiances as normative? These are, as Pressly documents, far more difficult pockets of ambiguity to unpack. They exist off the usual tourist map. They take us down county routes and dirt roads, not to well-marked interstate exits. The many stories of Black Floridians during this period remain to be written. It will take continued efforts, such as A Southern Underground Railroad, to draw them out.

About the Author

Thomas Hallock received his PhD from New York University. He is the author of From the Fallen Tree: Frontier Narratives, Environmental Politics and the Roots of a National Pastoral, 1749–1826 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003) and the co-editor of Early Modern Ecostudies: From the Florentine Codex to Shakespeare (New York: Palgrave Macmilian, 2008), William Bartram, the Search for Nature's Design: Selected Art, Letters and Unpublished Manuscripts (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010), and Travels on the St. Johns River: John and William Bartram (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2016). He recently published a series of travel and place-based essays that explain why he loves teaching the American literature survey, A Road Course in Early American Literature: Travel and Teaching from Atzlán to Amherst (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2022). In 2023, Southern Spaces published Hallock's multi-media article, "Draining Paradise: A Tour of Salt Creek in St. Petersburg, Florida."

Cover Image Attribution:

Earthworks at Prospect Bluff. Photo copyright by Thomas Hallock, 2025. Used by permission.Recommended Resources

Text

Blackhawk, Ned. The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023.

DuVal, Kathleen. Native Nations: A Millennium in North America. New York: Random House, 2024.

Landers, Jane. Black Society and Experience in Spanish Florida, 1565-1821. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999.

White, Richard. Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Web

Giddings, Joshua R. (1858). The Exiles of Florida: or, The Crimes Committed by Our Government against the Maroons, who Fled from South Carolina and other Slave States, Seeking Protection under Spanish Laws. Columbus, Ohio: Follett, Foster and Company, 1858.

https://archive.org/details/exilesoffloridao00gidd

Porter, Kenneth Wiggins; Amos, Alcione M.; Senter, Thomas P. (1996). The Black Seminoles: History of a Freedom-Seeking People. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1996.

https://archive.org/details/blackseminoleshi0000port

Whitman, Albery llson. Twasintas's Seminoles, or, Rape of Florida. St. Louis: Nixon-Jones Printing Co., 1890,

https://archive.org/details/twasintasssemino00whitrich