Overview

Fifty years after the fall of Sài Gòn, Vietnamese refugees reflect on their harrowing transnational migration histories. This essay features one remarkable journey—Humanitarian Operation refugees, formerly incarcerated in re-education camps and refugee detainment facilities, resettling in Nashville, Tennessee.

2025 marks fifty years since the fall of Sài Gòn and the communist takeover of Laos, Cambodia, and Việt Nam. While Vietnamese American communities commemorate this anniversary year of the loss of their former country, many Americans have little interest in revisiting this history or learning its lessons. Still wrenching in the minds of Vietnamese American refugees, the policy decisions of the subsequent Vietnamese state notoriously included the development of re-education camps and the incarceration of former government officials and civil servants. An enduring legacy of the post-Việt Nam War era, the cruel treatment of re-education camp detainees shaped the forced migration of thousands of former Southern Vietnamese political prisoners.

Many South Vietnamese sought new identities as they resettled in locations such as California, Texas, Washington State, Louisiana, and the DC metro area including Maryland and northern Virginia. Perhaps surprisingly, Tennessee also became home to generations of Vietnamese refugees and immigrants with intense transnational migration histories. One family’s story is that of my own, whose refugee experience does not follow the typical timeline of helicopter escapees and boat people. Rather, as Humanitarian Operation arrivals, my family’s history offers an illuminating narrative.1This essay draws upon excerpts from an oral history conducted by the author with Đỗ Phương Anh Linh in November 2020, as well as stories from March 2025 told by his younger sister, Đỗ Phương Anh Thư.

My grandfather, Đỗ Phương Anh, was born on July 3, 1935, in the Quảng Bình province of Central Việt Nam during the French Colonial period. In the late fifties and early sixties, Phương Anh was required to complete mandatory military service for young men in their twenties. A former teacher of Vietnamese literature and theology, he paused his teaching career in 1965 at Trường Trung Học Võ Tánh located in Nha Trang to serve as a lieutenant in the Army of the Republic of Việt Nam (Lục Quân Việt Nam Cộng Hòa), more familiarly known as the South Vietnamese Army. South Việt Nam’s government facilitated mass military mobilization in response to intense war escalation and the deployment of US combat troops. This meant my grandfather would leave his academic job to travel with his family to the provincial city of Sa Đéc. There, he was the military’s paymaster, responsible for distributing wages to the soldiers in the South Vietnamese Army, and was also a logistics officer, managing the local squad’s resources and supplies. He completed his assignment in 1970 and was allowed to return to his teaching position in Nha Trang.

As combat intensified, North Vietnamese forces encroached into South Việt Nam, forcing Phương Anh and his family to relocate to Sài Gòn in April 1975. During the following months, the collapse of the South Vietnamese government led to the detainment of former military personnel and civil servants. Upon his return to Nha Trang in May 1975, my grandfather was confronted by communist officials, arrested, and sent to a re-education camp. Too traumatic and horrific for him to recount, my grandfather’s stories and experiences in those camps are lost to time. Yet, the terrors he saw there would manifest perniciously. Years later, when family members brought up plans to return and visit Việt Nam, in total outrage, my grandfather exclaimed that he would never return to a country where he had experienced such atrocities.

Upon his release in 1982, marking seven years of incarceration, my grandfather faced eviction from his family home in Sài Gòn, forcing him, my father, his siblings, and my grandmother, Lê Thị Kim Hoa, to relocate to government-owned housing. A family of eight, they were crowded into a small, worn-out city property that had no furnishings and limited access to electricity. My father, Đỗ Phương Anh Linh, was born on August 6, 1964, in the city of Nha Trang of southern Việt Nam. Being the oldest son meant he would bear too soon the burden of standing in as the man of the house because of my grandfather’s incarceration. While Phương Anh was in the re-education camp, my grandmother and my father were the only two family members old enough to find jobs. However, neither of them could find decent-paying work in densely-populated Sài Gòn, especially while it was undergoing systematic economic changes as well as recovering from a disastrous war. Circumstances became dire as my father’s family grappled with extreme poverty and starvation. Yearning for new beginnings and exhausted from the suffering and hardship in their homeland, my father’s family decided that they needed to flee to the United States.

At their first getaway attempt, my grandfather and father, together with fifty-three other people, sought to escape Việt Nam by a fishing boat. After seven days of traveling on the South China Sea, commonly known as the East Sea or Biển Đông, a storm caused the boat to malfunction and forced a landing on nearby Côn Sơn island, once a part of French Indochina, but now claimed by the Vietnamese government. Everyone aboard was detained in the island’s prison. My father, age sixteen, was sentenced to one year of jail; my grandfather faced three years. Like many other prisons and detention camps in Việt Nam, conditions were horrible because of food scarcity, compact and crowded living facilities, forced intense physical labor, and a lack of sanitation.

Following my father’s release from the island prison in 1983, he returned to his family in Sài Gòn for a few days before attempting again to escape by boat. This time he travelled without family members to the small city of Cà Mau, where he joined with some seventy other people. Shortly after embarking, the ship’s poor condition caused it to flood. Cast up on a jungle shore, my father tried to find his way back to Sài Gòn, but was stopped by law enforcement at Cà Mau’s city border. He was detained and imprisoned again, this time in Cây Gừa, a local camp.

After months, my father was allowed to return to Sài Gòn and join his family. My grandfather remained imprisoned. The family’s income was left to my grandmother and father. For the following six months, my father’s job was driving people around the city on a cyclo, a three-wheel bicycle taxi. But he, and my grandmother, who sold bowls of sticky rice on the streets, were unable to earn enough to sustain the family and its small children.

After six months in Sài Gòn, my father and his ten-year-old younger brother, Đỗ Phương Anh Tuấn, attempted another escape. With almost no money they made it to Mỹ Tho to board a Mekong River boat that they hoped would take them to the coast. If they could reach the beaches, my father thought he could figure out a way to flee. As the boat drifted downriver, my father realized that the people who sold him the tickets were scammers. The boat was over-crowded and in a dangerously poor condition. The deck began filling with Mekong water. Everyone screamed in panic and fear, forcing the captain to make an emergency landing at a small island. Here, my father and his brother tried to hide in the jungle brush from soldiers and policemen. In the middle of the night, soldiers monitoring the island caught my father’s younger brother, age ten. My father had no choice but to turn himself in. They were sent to a nearby jail. Once the police determined that they were attempting to escape the country, they were sent to another island prison and subjected to forced physical labor. Sentenced for a year and a half, my father was required to harvest rice for ten hours a day in Việt Nam's hot and humid climate. Among other tasks, Anh Tuấn herded ducks into cages for selling in the farmers’ market. Only a child, he was released early. My father continued to be held.

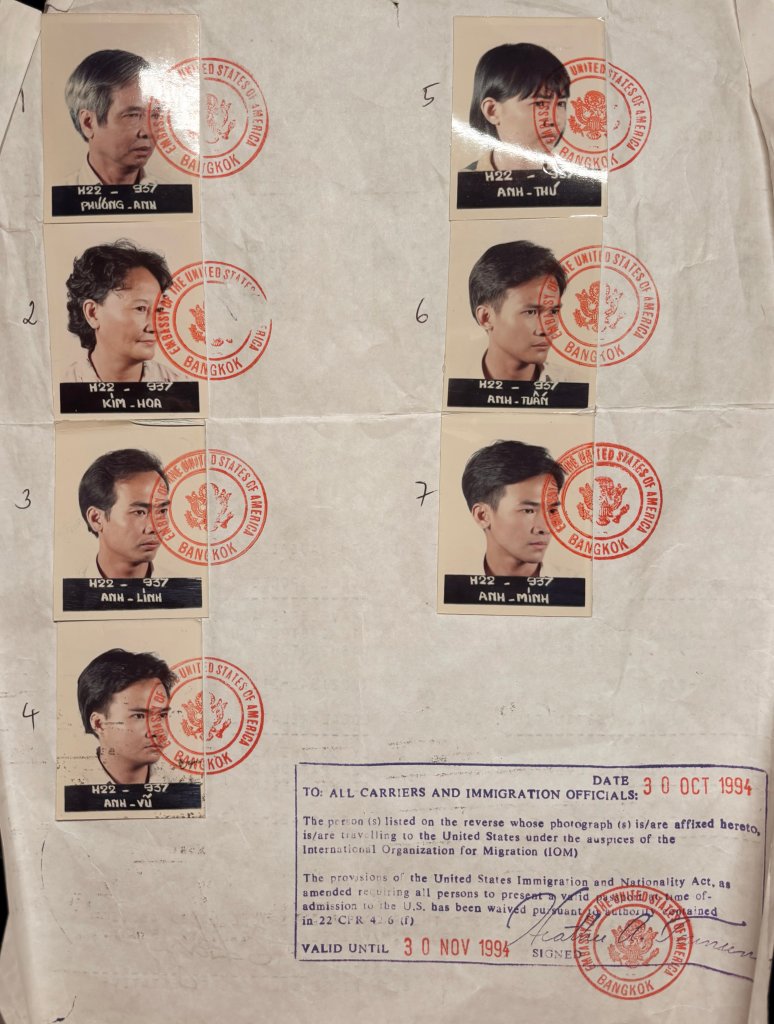

In the early 1990s, the United States began the Humanitarian Operation Program that allowed formerly imprisoned civil servants to seek political asylum. For everyone in my father’s family to be accepted into this program, they had to provide documentation of their time spent within the re-education camps. There was also much paperwork with the US Embassy concerning their applications for a passport and their medical history. After having gone through extended hardship, my father, Đỗ Phương Anh Linh, embarked on this life-changing journey.

In the final weeks of November 1994, my father, his parents, and all five of his siblings flew to Baltimore to reunite with his aunt, Đỗ Thị Kim Liên, and her family. Having lived in Maryland for about twenty years, Liên, and her husband, Lý Văn Đích, arrived in the United States among the initial waves of refugees following the fall of Sài Gòn. At the Baltimore airport, Đích welcomed his relatives and drove them to the family’s residence in Silver Springs. They immediately found work (for around five dollars an hour) at the dollar stores and laundry mats owned by their cousin, Lý Trang.

It had only been three months since my father arrived in Silver Springs when his uncle, Đỗ Quang Châu, phoned and convinced him to move to Tennessee. Châu, more familiarly known as Father Peter, was the former head pastor of St. Martha’s Catholic Church, the first Vietnamese American parish in the Nashville area. After enduring invasive investigations by Việt Nam’s communist government intent on locating the Catholic Church’s financial accounts and stored funds, Father Peter escaped Việt Nam in 1978 by boat and settled in a refugee camp in Thailand. His mother was sponsored in Cookeville, Tennessee, about an hour-and-a-half east of Nashville. To reunite with her, Father Peter flew from Thailand to Tennessee, officially beginning his religious service to a newly emergent Vietnamese Catholic community. Father Peter sought to establish a church where the Vietnamese could worship in their native language. In the nineties, Vietnamese Catholics were constantly relocated and displaced from various churches across the city, with parish staff falsely alleging that the Vietnamese refugees trashed the facilities. Father Peter ultimately led the construction of a new Catholic church in Ashland City that would be the cultural and spiritual hub for local Vietnamese American Catholics for two decades.

When Father Peter contacted my father, he spoke about the Nashville area’s lower cost of living along with its growing job market. My father was dubious, so he went alone to see for himself. He immediately found work at the Sunday School Publishing Board, a Baptist publishing company that created textbooks for churches in middle Tennessee. Father Peter had close connections with the board’s owner, opening the door for many Vietnamese refugees to work there. As Silver Springs, Maryland, became increasingly more crowded with Vietnamese migrants, the ability to find employment had become difficult. The language barrier for Vietnamese refugees meant they were all competing for similar jobs that required minimal English-speaking skills. In Nashville, it was easier to find work, especially physical labor jobs, that required little to no English. My father’s family was convinced that moving to Nashville was their best plan of action, and after six months they joined him there.

At the time, my father was living with his uncle, Đỗ Hữu Đề, who also worked with the Sunday School Publishing Board. Đề was formerly a police chief in the South Vietnamese government. He had previously traveled to the United States, before the war, to study in a police training academy before returning to his family in Việt Nam. Like many other civil servants in the South following the Việt Nam War, Đề was relocated to a harsh and torturous re-education camp. Đề stayed in this camp for ten years, facing starvation and exhaustion from intense physical labor. He was eventually allowed to leave Việt Nam and came to the United States in 1993, a year before my father’s family. Because of his previous studies in the US, Đề was proficient in English, making him a resource and translator among the Vietnamese immigrants. Đề also taught many Vietnamese, including my father and his siblings, how to drive.

My father’s family’s resettlement in Nashville began with a short stay with their Uncle Đề. Father Peter’s advice proved true, demonstrated by the ease with which everyone found employment. Their new jobs varied from working at the Sunday School Publishing Board, a hammer production site, and an electronic assembling company. Their incomes ensured enough financial stability for the family to move out of Đề’s home into a nearby apartment complex. My father and his siblings applied to Nashville State Community College to attain associate degrees. After about two years of clocking into their jobs, keeping up with their coursework, and all the while learning English, the family had saved enough for a major milestone—purchasing a house in West Nashville, where they continue to reside. Finishing their programs at Nashville State, my father and all of his siblings except for his sister transferred to local universities such as Tennessee State and Middle Tennessee State.

By the time most of the family earned degrees (my father’s was in computer science), they had lived in the United States for over five years, the minimum residency to apply for citizenship. They believed this was important, and necessary, because of the legal rights and protections. They saw the right to vote as the most valuable privilege of gaining citizenship, a freedom they were not afforded under Việt Nam’s communist regime. The United Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) approved their applications and set appointments for their citizenship test – which included a short written section and an oral examination on US history and civics. They all passed on their first tries and were naturalized at a local courthouse in 2000.

Next, my father returned to Việt Nam to marry his long-distance girlfriend, my mother. He helped her get a green card and become a permanent resident. They travelled back to the US in October of 2001 where they were expecting a baby boy. Through countless obstacles and tribulations, my mother and father were finally able to settle and raise a family.

The new life in Tennessee presented challenges and opportunities. The growing Vietnamese population in Nashville found it difficult to attain the varieties of fresh produce, fermented sauces, and particular meat cuts used in their traditional cooking, creating a sense of nostalgia and longing for their beloved dishes.2There are few reliable sources to estimate how many Vietnamese people live in Nashville. As of July 2023, 3.5% of the population in the Nashville-Davidson metropolitan area identifies as Asian (approximately 24,000 people). https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/nashvilledavidsonmetropolitangovernmentbalancetennessee/PST045223 Many Asian groceries in Nashville were owned by Lao refugees and immigrants, none that regularly carried the items desired by the Vietnamese. My father and his family took on the challenge of opening a grocery store—now one of the oldest Vietnamese-owned establishments in the area. Along with hoping to fulfill the demand for Vietnamese foods, they wanted to ensure that if any of the siblings were to ever be unemployed, they would have a safety net at the family business. Opening on September 15, 2000, the Đỗ family named their business Bách Thảo Market to represent the diverse selection of fragrant herbs, root vegetables, and leafy greens for sale.

Opening a family business came at a substantial cost. Cleaning out their bank accounts and maxing out credit cards, the Đỗ’s took on a major risk. Driving a box truck fifteen hours each way between Tennessee and Texas, my father was responsible for retrieving two to three pallets of produce and goods that would be sold at Bách Thảo. He carried pillows and blankets with him to create a makeshift truck bed at rest areas on the interstate. My father drove weekly to Texas for seven to eight years until a specialized produce distributor opened in Memphis. In June 2017, Bách Thảo Market was renamed to Little Sài Gòn Market to advertise towards an American clientele, who my family believed would more easily associate Sài Gòn with Vietnamese products versus the less familiar Bách Thảo. Little Sài Gòn Market remains in operation today, owned by Đỗ Phương Anh Thư and Đỗ Phương Anh Minh, the youngest daughter and son among my father’s siblings.

Fifty years after the fall, Vietnamese refugees devastated by war, incarcerated for “re-education,” and displaced to unexpected locations across the United States have created vibrant cultural enclaves. They leave enduring legacies in their new homes, often unknowingly, through simply keeping alive the memories of their motherland. My family’s resilient history, one stream in an intricate Vietnamese American diaspora, suggests the complexity of refugees’ stories and lived experiences—as well as the necessary work of recovering and interpreting this history.

About the Author

Anhhuy Do is a graduate student in history at Princeton University. Born and raised in Nashville, he is an aspiring scholar of Vietnamese refugees and Asian American history in the US South.

Cover Image Attribution:

Photo courtesy of Anhhuy Do.Recommended Resources

Text

Huynh, Jennifer. Suburban Refugees: Class and Resistance in Little Saigon. University of California Press, 2025.

Joshi, Khyati Y. and Jigna Desa. Asian Americans in Dixie: Race and Migration in the South. University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Lipman, Jana. In Camps: Vietnamese Refugees, Asylum Seekers, and Repatriates. University of California, 2020.

Nguyen, Phuong Tran. Becoming Refugee American: The Politics of Rescue in Little Saigon. University of Illinois Press, 2017.

Vu, Roy. Farm-to-Freedom: Vietnamese Americans and Their Food Gardens. Texas A&M University Press, 2024.

Web

Oral Histories:

University of California, Irvine. "Viet Stories: Vietnamese American Oral History project." https://calisphere.org/collections/36/.

Texas Tech University: The Vietnam Center and Sam Johnson Vietnam Archive. "The Oral History Project of the Sam Johnson Vietnam Archive." https://www.vietnam.ttu.edu/oralhistory/.

Vietnamese Heritage Museum. "Oral History: 'Re-education' Camp Survivor." https://vietnamesemuseum.org/our-projects/oral-history/re-education-camp-survivor/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | This essay draws upon excerpts from an oral history conducted by the author with Đỗ Phương Anh Linh in November 2020, as well as stories from March 2025 told by his younger sister, Đỗ Phương Anh Thư. |

|---|---|

| 2. | There are few reliable sources to estimate how many Vietnamese people live in Nashville. As of July 2023, 3.5% of the population in the Nashville-Davidson metropolitan area identifies as Asian (approximately 24,000 people). https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/nashvilledavidsonmetropolitangovernmentbalancetennessee/PST045223 |