Overview

Scott L. Matthews reviews Berkley Hudson's O. N. Pruitt’s Possum Town: Photographing Trouble & Resilience in the American South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2022).

In 1971, a Walker Evans retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art inspired critic Hilton Kramer to reflect on the Evan's enduring influence: "For how many of us, I wonder, has our imagination of what the United States looked like and felt like in the nineteen-thirties been determined not by novel or play or a poem or a painting or even by our own memories, but by a work of a single photographer, Walker Evans."1Kramer quoted in Tom Rankin, "'The Injuries of Time and Weather,'" Southern Cultures 13, no. 2 (2007): 9. Swap out "the United States" for "the US South," and insert some of Evans's contemporaries, including Dorothea Lange, Jack Delano, Ben Shahn, Marion-Post Wolcott, and Margaret Bourke-White, and Kramer's point becomes even more apt. They all photographed a diverse cross section of the United States for various publications and New Deal programs, such as the Farm Security Administration, but the small-town, rural South was the site and subject of their most recognized work. The vivid immediacy of their photographs—and their ubiquity in magazines, books, and exhibits—has made it possible to think of them as surrogates for personal experience and memory. As a cultural imaginary, a "Documentary South," has often served as "the thing itself," a persuasive counterpoint to popular culture ventriloquisms. As Margaret Bourke-White wrote of You Have Seen Their Faces, her 1930s photo-text book about rural poverty, it "may not be the South of song and story, but it is the South that you bring back on sheets of Panchromatic film."2Jonathan A. Silverman, For the World to See: The Life of Margaret Bourke-White (New York: Viking Press, 1983), 80.

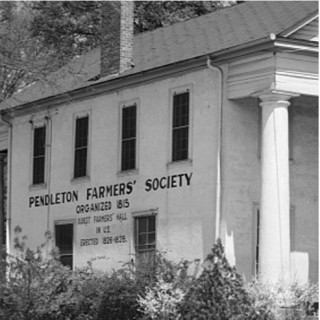

The reality is that up until about 1971, if residents of southern cities, towns, or farms thought about the role of photography, most would not have considered (or known of) Bourke-White or Evans. However, they may have been aware of locals who pursued photography as a profession, a passion, or perhaps both by creating snapshots made with Brownies and other Kodaks. Many of these photographers owned their own studios or made photographs for local publications and other purposes. Their portraits and photographs of street scenes, church services, rural life, and landscape often resembled an album whose intended audience was also its subject. Each town and city seemed to have its acknowledged "picture man" or woman, people such as Mike Disfarmer of Heber Springs, Arkansas; Paul Kwilecki of Decatur County, Georgia; Hugh Mangum of Durham, North Carolina; J. W. Otts of Hale County, Alabama; O. N. Pruitt of Columbus, Mississippi; Paul and Layfette Buchanan of western North Carolina; Sam F. Vance, Jr. of Kernersville, North Carolina; Bayard Wooten of New Bern and Chapel Hill, North Carolina; T. R. Phelps of southwest Virginia; Rufus W. Holsinger of Charlottesville, Virginia; and many others.

Black community photographers in the South, including P. H. Polk of Tuskegee, Alabama, Richard Samuel Roberts of Columbia, South Carolina, and Rev. Lonzie Odie Taylor of Memphis, Tennessee, played particularly important roles during the Jim Crow era when Black photographers were largely excluded from the staffs of national magazines and many New Deal agencies, including the FSA. Gordon Parks was the FSA's only Black photographer during the agency's eight-year existence between 1935 and 1943, serving as a Rosenwald fellow for one year in 1942. Black photographers documented aspects of Black life, particularly middle-class life, that white photographers ignored or could not access. Their photographs ultimately transcended their local purposes and created what bell hooks has called "a counterhegemonic world of images" that rebutted the racist caricatures found in popular culture and in the work of some white photographers.3bell hooks, Art on My Mind: Visual Politics (New York: The New Press, 1995), 57.

For most Black and white community photographers, local demands and conventions of circulation limited the reach of their images. That has changed in recent years thanks to the work of some dogged historians and archivists. Knowledge about local photographers has grown since the 1970s when scholars, partly under the influence of new social history and ethnographic movements, began retrieving and saving photographers' archives from oblivion and writing life histories. More recently, libraries have digitized some of these archives, making them more accessible to scholars and the public. Presses have published exquisite books about local photographers that combine beautiful layouts with insightful scholarship. The "Documentary Arts and Culture" series of University of North Carolina Press presents stunning books that chronicle the lives and work of a few of these photographers: One Place: Paul Kwilecki and Four Decades of Photographs from Decatur County, Georgia edited by Tom Rankin; Where We Find Ourselves: The Photographs of Hugh Mangum, 1897–1922 edited by Margaret Sartor and Alex Harris; O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town: Photographing Trouble and Resilience in the American South by Berkley Hudson.4Examples of books and articles on some of the local photographers mentioned in this review essay include, Julia Sully, Disfarmer: The Heber Springs Portraits, 1939–1946 (Danbury, NH: Addison House, 1976); Ann Hawthorne, The Picture Man: Photographs by Paul Buchanan (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993); David Moltke-Hansen, "Seeing the Highlands: Southwestern Virginia through the Lens of T. R. Phelps," Southern Cultures 1, no. 1 (1994): 23–49; Belena S. Chapp, et al, Through These Eyes: The Photographs of P. H. Polk (Newark, DE: University Gallery, University of Delaware, 2001); Ralph E. Lentz, II, W. R. Trivett, Appalachian Pictureman: Photographs of a Bygone Time (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2001); Rob Amberg, Sodom Laurel Album (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); Rah Bickley, "Sam F. Vance, Jr. 'Character-Taker': The Faces of Small-Town and Rural North Carolina, 1930s–1940s," Southern Cultures 13, no. 2 (2007): 78–94; Tom Rankin, One Place: Paul Kwilecki and Four Decades of Photographs from Decatur County, Georgia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013); Margaret Sartor and Alex Harris, Where We Find Ourselves: The Photographs of Hugh Mangum, 1897–1922 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018); James T. Campbell and Elaine Owens, Mississippi Witness: The Photographs of Florence Mars (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2019); Thomas L. Johnson and Phillip C. Dunn, A True Likeness: The Black South of Richard Samuel Roberts, 1920–1936 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2019); Berkley Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town: Photographing Trouble & Resilience in the American South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2022).

Decades in the making, Hudson's extraordinary book explores the life and work of Otis Noel Pruitt (1891–1967), a white Mississippian who between the 1920s and 1950s served as the "de facto documentarian" for Lowndes County, Mississippi, its seat, Columbus (nickname Possum Town), and surrounding towns and countryside in the northeastern part of the state. An emeritus professor of journalism at the University of Missouri, Hudson grew up in Columbus in the 1950s and knew Pruitt as the "picture man." Pruitt photographed important family gatherings at the "rambling, two-story Victorian filled with Pekingese and antiques" where Hudson's grandmother lived. His photographs adorned the walls of Hudson's childhood home. In the 1970s, as a student journalist and photographer, Hudson began working with friends from Columbus—including photographer Birney Imes, photographer and folklorist Mark Gooch, David Gooch, and Jim Carnes—to track down and acquire Pruitt's archive of 88,657 negatives and 2,000 glass plates, which they donated to the Wilson Library at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill in 2012.5Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 2–5.

Hudson selected nearly two hundred images from Pruitt's sprawling archive to feature in O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town. They are thoughtfully sequenced to tell a coherent and dichotomous story of "Trouble & Resilience." On their own, Pruitt's evocative and deeply disturbing photographs make this a remarkable book, but it's Hudson's poignant writing and his personal connections to Pruitt, Columbus, and its people that make the book especially valuable.

In a series of short interspersed essays, Hudson tells a history of Columbus and Lowndes County, Mississippi and reveals narratives behind some of the photographs Pruitt made. Hudson weaves his research and memories with the memories of others he or his colleagues interviewed, including people featured in the photographs or their descendants, as well as Pruitt's. These voices bring life and death into the photographs. With emotional resonance, they turn abstractions (race, class, gender, place) into a nexus of experiences and relationships. They prod us to reconsider interpretations of photographs we think we know.

Born on a farm in south central Mississippi, O. N. Pruitt came of age while Eastman Kodak was popularizing photography. The introduction of affordable and portable box cameras, such as the Brownie, around the turn of the century transformed "one of the most envied accompaniments of high birth"—family portraits—into an almost common possession.6"Old Photographs," The Living Age, 279, December 13 (1913): 689. Pruitt bought his first camera to make pictures of his young children. Before long he was using his Brownie 122 to photograph timberland for landowners looking to sell. By 1915, he was a full-time photographer. To hone his craft and make himself more marketable, he studied for a year at the Illinois School of Photography in 1916. When he returned to Mississippi, he opened his own studio in the town of Newton near his birthplace. Three years later, he and his family moved ninety miles northeast to Columbus where he began working at the studio of a German immigrant named Henry Emil Hoffmeister. In 1921, Pruitt bought out his boss and began establishing himself as the area's premier photographer.7Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 9.

As a businessman, Pruitt made studio portraits of Black and white people while the police and insurance companies paid him for photographs of homicide and lynching victims, car accidents, and damage and deaths from natural disasters. Pruitt roamed the area's streets and backroads on his own as a documentary artist. He had an expansive eye and a knack for recording habits and rituals from cradle to grave. He photographed infants in his studio and the dead in their caskets, baptisms and executions, fox hunts and "freak" shows, cotton farmers and Klan rallies, Black Sunday School classes, and Kiwanis Club members in blackface. "His photographs," writes Hudson, "capture scenes of the ordinary graces of everyday life, ethnic identity, and race relations as well as brutal power, full of excruciating suffering." They offer a vivid "photobiography of a time and place" from the perspective of a white photographer living in the Jim Crow South.8Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 1, 9–11. What these photographs document most of all, however, is the pervasive situation of racial segregation and white domination.

Irony and contradiction saturate Pruitt's persona and his depiction of Lowndes County's segregated society. A member of "the white male Columbus power structure," he was a gregarious man who said and wrote nothing about his photographic interests or inspirations; he faithfully attended Sunday school and enjoyed telling "smutty jokes"; he was a good ole' boy who loved to hunt and fish and who used his camera to cross the color-line by making beautiful, sometimes intimate, portraits of Black clients, including the president of the local NAACP. Even the use of his most widely recognized photograph was paradoxical. Some whites turned his 1935 image of two Black lynching victims into postcards, while the Chicago Defender published it under the caustic heading "White Civilization." Three decades later, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) used the same photo in a voting rights poster.9Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 10–11, 13.

Columbus sits astride two recognized ecoregions: the last undulations of Appalachia, known in the area as the Tombigbee Hills, roll north and east of town while a band of fertile Black Belt prairieland spreads south and west. Between 1920 and 1960, the years Pruitt photographed there, the town's population grew from 10,501 to 24,771, all the while having an almost equal number of Black and white residents. The guidebook published by Mississippi's Federal Writers' Project in 1937 romanticized Columbus as "a comfortable old-tree shaded town" with homes "characteristic of the lavish ante-bellum period in which they were built. It is the junction of the Old South with the New, with gracious lines of Georgian porticos forming a belt of mellowed beauty about a modern business district." On the northside of town, the "Negro section," sat "low-roofed, red frame houses . . . festooned with wisteria and shaded by umbrella chinaberry trees and tall, brightly colored sunflowers."10Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 19. The everyday inequalities and racist terror missing in the guidebook descriptions can't help but edge their way into the photos of Pruitt.

Hudson acknowledges that his study of the conservative Pruitt, who photographed him in the segregated world of his youth, helped him find "connections to my life—unknown, unconscious, or purposefully hidden. With this project, I learned heartrending stories I wish someone had told me long ago." From the photographs, Hudson "learned about executions and lynchings that my mother and father knew about but never mentioned. I learned about baptisms in the 1920s and 1930s in the Tombigbee River where Black and white church groups gathered in a measure of biracial Christian harmony. As children, my mother and my uncles went to these on Sunday afternoons near their home and a few blocks from where I one day would live."11Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 5 and 7.

Despite his personal ties and long work on the project, Hudson avoids turning his study of Pruitt's images into an awakening memoir. As he writes in the opening chapter, "The stories embedded here do not simply belong to me. . . . I alone cannot tell the stories of Pruitt's photographs. That requires a collective effort of reflection and conversations among all kinds of people with all kinds of backgrounds and beliefs."12Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 5. The power of O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town comes from the interplay and juxtaposition of Hudson's own stories of Pruitt's photographs with those of people whose backgrounds and experiences are, or were, unlike his own.

In the essay "Catfish Alley Fire," which accompanies Pruitt's book-cover photograph of the same title, Hudson braids his history of Columbus's former "one-block-long strip of flourishing Black businesses," with the memories of Black and white residents. The effect turns the photograph into a palimpsest of overlapping and competing stories. Although a Black business district, white men visited Catfish Alley to play poker, eat fish and barbeque, and drink illegal whiskey. Some later romanticized it in their memories, portraying it as a place redolent of fried fish and moonshine where the proprieties of middle-class life could be left behind. "Drink whiskey and eat fish," one white man remembered, "That's about all it was to it." But for Black businessman Edward C. Bush, Catfish Alley was a place of Black economic and cultural independence, a refuge from the worst of Jim Crow's indignities.13Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 110–111.

Pruitt's "Catfish Alley Fire" photograph represents some small portion of the tension between these two sets of memories. Taken about 1940, it shows people congregating on the street to watch the fire department respond to a blaze that's out of view. It's an allusive image, a "tableau of street theater," Hudson writes, that corrals the contradictions of Jim Crow into one city block. Black and white, mostly men, stand in the vicinity of a sign for a "Colored Café" and stare at the fire looming beyond the left frame. It's the rare event that breaks the everyday, but in their proximity, Black and white are distanced, alienated, from each other. The fire hoses snaking along the street form cordons and ligatures, markers of segregation and the ties that bound Black and white together despite it.14Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 110–111.

The hose can also be read as a rope, a symbol of the white supremacist violence—real and threatened—that runs through Pruitt's photographs in this book. Possum Town opens with a series of beautiful portraits of Black and white sitters and images that illuminate the landscape. Then, abruptly, Hudson presents a photograph of a Black boy with a bloodied nose and blood-stained shirt. He stares straight at Pruitt, wounded but impassive or perhaps stunned to see a camera pointing at him. The white boy over his left shoulder holds a nearly clinched left fist that correlates with the blood dripping from the Black boy's right nostril. The white boy's face conveys a mixture of satisfaction and reluctance as if the white men who stand behind him had goaded him into the fight for their more evident pleasure. The Black bystanders seem variously engaged and uneasy, perhaps tempering their deeper feelings about the bloodshed because of the presence of white men and because they know that this fight, even involving youths, is a species of the violence whites used to maintain power. Hudson's decision to juxtapose this image with a pastoral photograph of two white men standing in a field of oats on the opposite page suggests how suddenly "trouble" can shatter the façade of tranquility and how quickly some want to forget it.15Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, x.

Hudson's book includes two photographs that frame white killings of Black men. The first, on a left-facing page, from 1934, shows James Keaton, a Black man, standing at the gallows with white officials who will soon carry out his execution by hanging. On the opposite page appears one of Pruitt's 1935 photographs of the bodies of Bert Moore and Dooley Morton hanging from a tree following their lynching by a mob. These images are preceded by two photographs of different blackface minstrel shows performed by white youths and Kiwanis Club members and one image of the Klan marching at night through Columbus and passing in front of the photographer's studio. By placing these photographs immediately before the images of executions, Hudson suggests how ritualized theatrical and physical violence conspire, how one enables the other in white racism's bloody crucible.16Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 149–161.

Hudson's accompanying essay to these photos provides another layer of context. In a section on Keaton's execution, Hudson explains the historical significance of Pruitt's photograph: it was the last time officials carried out a "legal" execution by rope hanging in Mississippi. An all-white, all-male jury convicted Keaton of killing a white gas station owner, although a white woman who worked nearby said he was innocent and that she knew who the actual killer was. Keaton, it turns out, was prosecuted by future US Senator and arch segregationist, John Stennis, who implored the jury to convict and "help advance civilization by removing this cancer."17Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 152–153.

Pruitt's photograph of Keaton at the gallows looks like a re-creation of a scene from some macabre play, which, of course, it is in a sense. Most of the men, including Keaton, feign grins except for the official on the far right who stares at Pruitt's camera with stern self-importance and smugness. Spectators peer from below and behind the scaffold, including through a courthouse window where, in one case, the camera's flash caused a man's eyes to emit a spectral glow. Hudson calls this a "tableau vivant, a living picture, at the death's moment," though it's also a tableau mort, one Pruitt took in service of white supremacy. Though not pictured, Black people, including preachers, writes Hudson, were present outside the courthouse when Pruitt made the photograph at 2 a.m. on May 25. "On the courthouse lawn for hours before the execution, they had sung spirituals through the night." Hudson's sentence evokes the Black presence while stressing their physical absence from a cropped and sanitized image.18Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 152–153.

Just over a year later, in July 1935, Pruitt, at the request of the sheriff, photographed Bert Moore and Dooley Morton hanging from an oak tree after a white mob lynched them in a churchyard eight miles south of Columbus. Unlike the Keaton execution image, only one white man appears here and he kneels with his back to the camera, "gathering their pant legs into a grasp," Hudson writes, "apparently to keep the bodies steady for the photograph."

The photograph remains Pruitt's most recognized and widely circulated, and its divergent uses have mirrored the contradictions of its creator. White supremacists made it into postcards, while Nazis used or referenced it as propaganda to expose American barbarism, as did the Black press, including the Chicago Defender, Jet, and Afro World. In the 1960s, SNCC used the photograph on posters to promote voting rights in Mississippi. More recently, it was used in the 2016 documentary, I Am Not Your Negro, by Raoul Peck based on an unpublished James Baldwin manuscript, and in a 2021 CNN special about Marvin Gaye's song, "What's Going On."19Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 155 and 213.

Thanks to Hudson's book, the public can now see and interpret this photograph in light of Pruitt's broader archive, or at least a portion of it. The extraordinary range of Pruitt's photographs, and the vivid stories Hudson tells about them, offers readers a unique opportunity to see the relationship between the quotidian habits and brutal horrors of life in a Mississippi Black Belt town during the depths of Jim Crow. Seen alongside the work of contemporary Black community photographers such as Richard Samuel Roberts and Rev. L. O. Taylor, Possum Town can also shed light on how whiteness and the strictures of segregation result in an archive that obscures as much as it reveals. So far, librarians at UNC, Chapel Hill, where Pruitt's work is located, have only been able to digitize a small portion of Pruitt's massive collection. As more images become available for public access in the future, other curators can build their own chronicles of Pruitt's work on Hudson's remarkable foundation.

About the Author

Scott L. Matthews is a professor of history at Florida State College at Jacksonville. He is author of Capturing the South: Imagining America's Most Documented Region (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018) and "John Cohen in Eastern Kentucky: Documentary Expression and the Image of Roscoe Halcomb During the Folk Revival."

Cover Image Attribution:

Church Halloween party during World War II. Photograph by O.N. Pruitt.Recommended Resources

Text

Civil Rights Congress. We Charge Genocide: The Historic Petition to the United Nations for Relief from a Crime of the United States Government Against the Negro People. New York: International Publishers, 1952.

Hudson, Berkley. "O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town: The 'Modest Aspiration and Small Renown' of a Mississippi Photographer, 1915–1960." Southern Cultures 13, no. 2 (2007): 52–77.

Latus, Janine. "Possum Town in Black and White." Humanities 43, no. 1 (2022).

Matthews, Scott L. Capturing the South: Imagining America's Most Documented Region. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Rankin, Tom. One Place: Paul Kwilecki and Four Decades of Photographs from Decatur County, Georgia. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2013.

Web

"2 Negroes lynched by Mississippi Mob; Deputy Sheriff Overpowered as He Takes Men From Columbus for Safekeeping." The New York Times. July 16, 1935. https://www.nytimes.com/1935/07/16/archives/2-negroes-lynched-by-mississippi-mob-deputy-sheriff-overpowered-as.html.

Arnold, T., Ayers, N., Madron, J., Nelson, R., Tilton, L., Wexler, L. Photogrammer. https://photogrammar.org/about

Auslander, Mark. "Contesting the Roadways: The Moore's Ford Lynching Reenactment and a Confederate Flag Rally, July 25, 2015." Southern Spaces. August 19, 2015. https://southernspaces.org/2015/contesting-roadways-moores-ford-lynching-reenactment-and-confederate-flag-rally-july-25-2015/ .

Christensen, Lauren. "'From the Dustbin of History,' a Photo Archive of the Jim Crow South." The New York Times. March 10, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/10/books/review/o-n-pruitt-possum-town.html.

Liles, Lindsey. "The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of Possum Town." Garden & Gun. January 24, 2022. https://gardenandgun.com/slideshow/the-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly-of-possum-town/.

Rankin, Tom. "Reframing Resistance: A Review of Freedom Now!" Southern Spaces. December 15, 2015. https://southernspaces.org/2015/reframing-resistance-review-freedom-now/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Kramer quoted in Tom Rankin, "'The Injuries of Time and Weather,'" Southern Cultures 13, no. 2 (2007): 9. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Jonathan A. Silverman, For the World to See: The Life of Margaret Bourke-White (New York: Viking Press, 1983), 80. |

| 3. | bell hooks, Art on My Mind: Visual Politics (New York: The New Press, 1995), 57. |

| 4. | Examples of books and articles on some of the local photographers mentioned in this review essay include, Julia Sully, Disfarmer: The Heber Springs Portraits, 1939–1946 (Danbury, NH: Addison House, 1976); Ann Hawthorne, The Picture Man: Photographs by Paul Buchanan (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993); David Moltke-Hansen, "Seeing the Highlands: Southwestern Virginia through the Lens of T. R. Phelps," Southern Cultures 1, no. 1 (1994): 23–49; Belena S. Chapp, et al, Through These Eyes: The Photographs of P. H. Polk (Newark, DE: University Gallery, University of Delaware, 2001); Ralph E. Lentz, II, W. R. Trivett, Appalachian Pictureman: Photographs of a Bygone Time (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2001); Rob Amberg, Sodom Laurel Album (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); Rah Bickley, "Sam F. Vance, Jr. 'Character-Taker': The Faces of Small-Town and Rural North Carolina, 1930s–1940s," Southern Cultures 13, no. 2 (2007): 78–94; Tom Rankin, One Place: Paul Kwilecki and Four Decades of Photographs from Decatur County, Georgia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013); Margaret Sartor and Alex Harris, Where We Find Ourselves: The Photographs of Hugh Mangum, 1897–1922 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018); James T. Campbell and Elaine Owens, Mississippi Witness: The Photographs of Florence Mars (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2019); Thomas L. Johnson and Phillip C. Dunn, A True Likeness: The Black South of Richard Samuel Roberts, 1920–1936 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2019); Berkley Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town: Photographing Trouble & Resilience in the American South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2022). |

| 5. | Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 2–5. |

| 6. | "Old Photographs," The Living Age, 279, December 13 (1913): 689. |

| 7. | Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 9. |

| 8. | Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 1, 9–11. |

| 9. | Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 10–11, 13. |

| 10. | Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 19. |

| 11. | Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 5 and 7. |

| 12. | Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 5. |

| 13. | Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 110–111. |

| 14. | Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 110–111. |

| 15. | Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, x. |

| 16. | Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 149–161. |

| 17. | Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 152–153. |

| 18. | Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 152–153. |

| 19. | Hudson, O. N. Pruitt's Possum Town, 155 and 213. |