Overview

Evan C. Rothera reviews Carl Lawrence Paulus's The Slaveholding Crisis: Fear of Insurrection and the Coming of the Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2017).

Review

Warning the governor of Kentucky that the white South stood on the brink of destruction in 1860, secession commissioner Stephen F. Hale wrote that Lincoln's election "inaugurates all the horrors of a San Domingo servile insurrection, consigning her citizens to assassinations and her wives and daughters to pollution and violation to satisfy the lust of half-civilized Africans."1Charles B. Dew, Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War, Fifteenth Anniversary Edition (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2016), 120. Hale sent his letter to Governor Beriah Magoffin of Kentucky. Hale's letter appeared nearly seventy years after the Haitian Revolution began and fifty-five years after Haiti won independence from France. Nevertheless, as Carl Lawrence Paulus demonstrates in The Slaveholding Crisis: Fear of Insurrection and the Coming of the Civil War, Hale's lurid images and graphic language resonated with many white southerners fearful about the lessons a free black republic might hold for the nearly four million people held in chattel bondage in the United States.

The contention that "the fear of a revolt—or revolution—being mounted by the enslaved became a defining characteristic of the slaveholding South" is not new (3). One of the strengths of The Slaveholding Crisis is its broad survey of the antebellum period through the perspective of American exceptionalism, which, according to Paulus, proslavery leaders "defined as the ability to employ either a congressional or states' rights approach to defend and perpetuate the institution of slavery" (5). Planters utilized the ideology of US uniqueness to attack anyone who attempted to interfere with slavery by accusing abolitionists of being dupes of the scheming British. The spatial dimensions of Paulus's book are noteworthy as he considers how Haiti, the British West Indies, Texas, and Mexico influenced slaveholder and abolitionist thought, US domestic politics, and ideas about the role of the United States in the world. The Slaveholding Crisis is certainly not the first book to pursue these influences; nevertheless, Paulus examines how each of these places, in turn, helped shape the development of ideas about American exceptionalism.

![Incendie du Cap [Burning of Cape Francais], Saint-Domingue, 1820. Frontispiece by unknown creator. Originally published in Saint-Domingue, ou Histoire de ses revolutions (Chez Tiger, 1820). This image is a frontispiece from a history of the Haitian Revolution, published in France about ten years before US planters took action to suppress slave rebellions on a federal scale. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in public domain. Incendie du Cap [Burning of Cape Francais], Saint-Domingue, 1820. Frontispiece by unknown creator. Originally published in Saint-Domingue, ou Histoire de ses revolutions (Chez Tiger, 1820). This image is a frontispiece from a history of the Haitian Revolution, published in France about ten years before US planters took action to suppress slave rebellions on a federal scale. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in public domain.](https://i0.wp.com/southernspaces.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Rothera_002_RevolteGeneral.jpg?ssl=1)

Incendie du Cap [Burning of Cape Francais], Saint-Domingue, 1820. Frontispiece by unknown creator. Originally published in Saint-Domingue, ou Histoire de ses revolutions (Chez Tiger, 1820). This image is a frontispiece from a history of the Haitian Revolution, published in France about ten years before US planters took action to suppress slave rebellions on a federal scale. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in public domain.

In 1789, many US citizens gloried in the spread of the ideals of the American Revolution to Europe. France seemed poised on the brink of becoming a "sister republic" and revolutionary optimism spread like wildfire. As the French Revolution became more radical, its ideas ignited the Caribbean and, in turn, revolution in Haiti petrified white people in the United States. "White racial communion," asserts Paulus, "trumped American ideological conflict between the Federalists and the Jeffersonian Republicans and the leadership of the first two political parties in the United States shared a similar reaction to the black revolution in the West Indies" (15). At times, Paulus lacks nuance in explaining the complexity and subtlety of the US-Haiti relationship. He also neglects significant recent work by Garry Wills and Ronald Angelo Johnson about the mutually beneficial relationship between the United States and Haiti in the late 1790s.2Garry Wills, "Negro President": Jefferson and the Slave Power (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 2003); Ronald Angelo Johnson, "A Revolutionary Dinner: US Diplomacy toward Saint Domingue, 1798–1801," Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 9, no. 1 (Winter 2011): 114–41; and Ronald Angelo Johnson, Diplomacy in Black and White: John Adams, Toussaint Louverture, and Their Atlantic World Alliance (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2014). Jefferson wanted nothing to do with Haiti. President John Adams and Timothy Pickering, his secretary of state, on the other hand, negotiated a treaty and developed strong bilateral relations with Toussaint Louverture. Paulus contends that South Carolina congressman Robert Goodloe Harper fretted about a potential invasion from the French West Indies, although he also worked with Pickering and Adams to support Louverture. Harper introduced Haitian envoy Joseph Bunel to various members of Congress so Bunel could convince politicians that Louverture had no interest in fomenting insurrection.3Compare Paulus, The Slaveholding Crisis, 23–24 and Johnson Diplomacy in Black and White, 58–67.

Revolutionaries carried ideas throughout the Atlantic World and spread ferment from one location to another. And so, it seems, did refugees. The arrival of French refugees from Haiti to the United States in the 1790s increased slaveholder fears as "the specter of Haiti's successful revolution appeared in everyday life" (20).4For other studies of the Haitian Revolution's impact on the United States see Ashli White, Encountering Revolution: Haiti and the Making of the Early Republic (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010) and James Alexander Dun, Dangerous Neighbors: Making the Haitian Revolution in Early America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016). Virginia slaveholders became apprehensive about black Virginians, both free and enslaved. Numerous historians have argued that slaves proved adept at transmitting information among themselves.5Although Paulus does not cite Julius S. Scott, "The Common Wind: Currents of Afro-American Communication in the Era of the Haitian Revolution" (PhD diss., Duke University, 1988) or Janet Polasky, Revolutions without Borders: The Call to Liberty in the Atlantic World (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015), both offer extended analysis of networks of communication among enslaved and free people throughout the Atlantic World. Certainly, Haitian events influenced rebellions in the United States.6Matthew J. Clavin, Toussaint Louverture and the American Civil War: The Promise and Peril of a Second Haitian Revolution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010). Revolution in the French West Indies "likely inspired Gabriel [Prosser] and his fellow insurrectionists to secure emancipation through violence" (29). Like Washington and Louverture, Gabriel, when he led a slave rebellion in Richmond in 1800, chose the title of general, not king. Haiti also played a "noteworthy role" in Denmark Vesey's 1822 uprising (42).

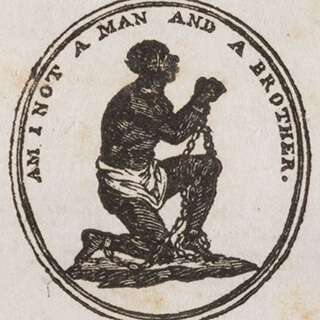

Paulus tends to depict planters as a homogenous class, not distinguishing between those who lived on the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts and in other slaveholding areas. Paulus might have considered whether planters in Tennessee and Missouri, or other landlocked states, were as obsessed with revolutions in the Caribbean as their counterparts in South Carolina and Louisiana. Geography may have created different ideas about revolutions, but this remains uncertain and, in any case, is not his book's major concern. Although terrified of revolt, planters believed northerners would suppress any rebellion and refuse to allow the slaughter of white people. Proslavery ideologues, however, soon began questioning this assumption. The postal system facilitated the distribution of incendiary abolitionist material such as David Walker's Appeal. Slaveholders expressed disgust when mayor Harrison Gray Otis of Boston refused to punish Walker. Otis distanced white Bostonians from Walker's radicalism and condemned his pamphlet, but this proved cold comfort to agitated slaveholders who "cared very little for Bostonian sympathies" (56). Nat Turner probably knew little about Walker's Appeal, but that did not stop planters from portraying Walker as the evil genius behind Turner's 1831 rebellion in Virginia. In response, slaveholders abandoned the "necessary evil" defense of slavery in favor of the "positive good" argument and sought to punish abolitionists. Planters began to fear that they could no longer count on northerners to protect them in the case of a slave rebellion.

Title page of Appeal, Boston, Massachusetts, 1830. Book by David Walker. Published by David Walker. Courtesy of Johns Hopkins University Sheridan Libraries, archive.org/details/walkersappealinf00walk/page/n4.

Paulus argues that a weighty change occurred in the 1830s: most planters "no longer saw a weak national government as key to slavery's perpetuation" and determined that "the South required more than the Constitution and its abstract protections" (90). President Andrew Jackson vowed to halt the antislavery mailing campaign and stop abolitionists from utilizing the postal system to drown the southern states in antislavery literature and periodicals. Jacksonian officials such as postmaster general Amos Kendall allowed the censorship and destruction of mail. The House of Representatives enacted James Henry Hammond's "Gag Rule" and tabled all antislavery petitions. Space, and control over space, mattered very much to planters, who no longer saw abolitionists as "moralists who, so consumed by their beliefs, did not understand the consequences of their actions." Rather, they believed them to be "evil enemies who purposely wanted to kill whites in the South indirectly by provoking slave revolt" (124). Some people in the northern states echoed these ideas and joined planters in denouncing abolitionists as traitors in league with Great Britain.

Emancipation in the British West Indies in 1833 increased US proslavery paranoia. Most planters believed Britain's plan of gradual, compensated emancipation would destroy West Indian economy and society. They also worried about their own future in a world where freedom seemed to be on the rise, and slavery on the defensive; perhaps they might end up like feckless Caribbean planters. Planters found some encouragement elsewhere. Some greedily turned their eyes toward Texas, a republic that had won independence from Mexico in 1836.7Paulus's analysis would have been strengthened by considering the essays in Jesús F. de la Teja, ed., Tejano Leadership in Mexican and Revolutionary Texas (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2010). Presidents Jackson, Van Buren, and Harrison shied away from Texas annexation, but President John Tyler and Secretary of State Abel Parker Upshur believed that Texas was a winning issue that could help Tyler secure a second term in 1844. Upshur argued that slavery helped guarantee US exceptionalism and worked to make Washington "the epicenter of proslavery power" (151). Parker and Tyler believed that the proslavery movement should use the levers of government power.

Senator Robert J. Walker of Mississippi became the voice for Texas annexation, framing it as "colonization without the cost." He and others "had no qualms saying that Texas, as a new member of the Union, would funnel black Americans away from the free states" (163). Walker's argument proved powerful, especially during the election of 1844, but also double-edged. "Northern Democrats who voted to approve annexation did not forget the proslavery guarantee from Robert Walker. They came to expect Texas to serve as a funnel for black population to move southward, away from their homes and cities" (166).8Paulus suggests the planter elite lost power in the 1840s. This contradicts a recent account of how politically powerful southerners created an aggressive foreign policy of slavery. See Matthew Karp, This Vast Southern Empire: Slaveholders at the Helm of American Foreign Policy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016), reviewed in Southern Spaces at https://southernspaces.org/2018/slaveholding-empire-southerners-federal-authority-and-slave-power-abroad. Walker's notion of Texas as a safety valve proved enticing to many northern Democrats and Paulus ably demonstrates the importance of space and place in driving political issues in the United States.

The fallout from Walker's argument became apparent in congressional debates over David Wilmot's 1846 Proviso barring slavery and involuntary servitude from any lands acquired from Mexico. Paulus's language becomes too exuberant when he asserts, "some members stood agape as the seemingly torpid monster of sectionalism rose back to life in the United States Capitol" (173). His analysis in previous chapters demonstrates that sectionalism was hardly torpid. Still, he is correct that the Wilmot Proviso had a potent impact on national politics. Many white southerners felt slighted, but they misread northern minds. Votes by northern Democrats in favor of the Proviso "had less to do with slavery and more to do with the black population of the United States" (185). Northerners remembered Walker's promises. They expected Texas to absorb black people and for new territory to be reserved for white men and their posterity. Proslavery ideologues, on the other hand, believed the Wilmot Proviso to be "the first step in the Abolitionist Power's plan to destroy the slave states and the plantation owners who governed them, not just the institution of slavery" (189). In addition, the proslavery movement turned against American exceptionalism. During the 1850s, southern radicals "came to believe that the exceptional nature of the Constitution had fallen by the wayside" (220). Ultimately, throughout the Secession Winter of 1860–1861, they repeatedly declared that the Constitution no longer protected them and, instead, represented "the provenance of their ruination" (234).

Throughout The Slaveholding Crisis, Paulus uses "American" to refer to the United States rather than the Americas, a practice he shares with many historians. This is troubling in a book that analyzes connections between the United States and the world. For instance, he writes: "The proslavery movement convinced itself that the South could not chance the fate of an American version of Toussaint rising in America while a Republican president held the reins of the military" (9). Paulus does not discuss other slaveholders in the Americas, save British planters. If he had, he might have considered whether slaveholders in Cuba, Brazil, and other countries developed similar exceptionalist ideas or suffered from similar fears. He could have been attentive to another spatial dimension—slaveholders in other geographies of the Americas.

Paulus also tends to be overly broad in his assessment of "proslavery southerners" (8)—there were plenty, after all, who never gave up on the Union. Secessionists exerted a mighty effort over many years to convince people to leave the Union and many never accepted their logic. Stephen F. Hale's lurid words, cited at the beginning of this review, captured a deep-seated fear seven decades in the making and resonated with the plantation South. But such sentiments proved unable to push Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, or Delaware out of the Union and it took the firing on Fort Sumter and Lincoln's call for troops to cause Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Tennessee to secede. These matters aside, The Slaveholding Crisis offers a thought-provoking analysis of how space and place drove slaveholders to refine their ideas about American exceptionalism and, ultimately, leave the Union.

About the Author

Evan C. Rothera is a lecturer in the Department of History at Sam Houston State University. His current book manuscript analyzes civil wars and reconstructions in the United States, Mexico, and Argentina between 1860–1880.

Cover Image Attribution:

Dessalines à la Crête-à-Pierrot, Haiti. Illustration by unknown creator. Originally published in Justin Chrysostome Dorsainvil’s Manuel d'histoire d'Haïti (Portu-Principis, 1934). Courtesy of MANIOC, University of the West Indies.Recommended Resources

Text

Clavin, Matthew J. Toussaint Louverture and the American Civil War: The Promise and Peril of a Second Haitian Revolution. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010.

Dun, James Alexander. Dangerous Neighbors: Making the Haitian Revolution in Early America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Geggus, David P., ed. The Impact of the Haitian Revolution in the Atlantic World. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2001.

Karp, Matthew. This Vast Southern Empire: Slaveholders at the Helm of American Foreign Policy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

Matthewson, Tim. "Jefferson and the Nonrecognition of Haiti." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 140, no. 1 (1996): 22–48.

———. A Proslavery Foreign Policy: Haitian-American Relations during the Early Republic. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2003.

White, Ashli. Encountering Revolution: Haiti and the Making of the Early Republic. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010.

Web

Early Caribbean Digital Archive. Northeastern University (Boston, MA). Accessed January 18, 2019. https://ecda.northeastern.edu.

Brown, Vincent. "Slave Revolt in Jamaica, 1760-1761." (Vincent Brown, 2012)

Foreman, Nicholas. "The History of the United States' First Refugee Crisis." Smithsonian Magazine. January 5, 2016. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/history-united-states-first-refugee-crisis-180957717/.

Gaffield, Julia. "Haiti and the Atlantic World." Accessed January 24, 2019. https://haitidoi.com/.

Haiti Collection. John Carter Brown Library (Providence, RI). Accessed January 18, 2019. https://archive.org/details/jcbhaiti&tab=collection.

Haiti: Miscellaneous Collections. The New York Public Library Digital Collections (New York, NY). Accessed January 18, 2019. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/haiti-miscellaneous-collections.

"The Haitian Revolution." Slavery and Remembrance. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Accessed January 18, 2019. http://slaveryandremembrance.org/articles/article/?id=A0066.

Rose, Christopher. "The Haitian Revolution." 15 Minute History. Podcast. February 6, 2013. https://15minutehistory.org/2013/02/06/episode-11-the-haitian-revolution/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Charles B. Dew, Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War, Fifteenth Anniversary Edition (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2016), 120. Hale sent his letter to Governor Beriah Magoffin of Kentucky. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Garry Wills, "Negro President": Jefferson and the Slave Power (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 2003); Ronald Angelo Johnson, "A Revolutionary Dinner: US Diplomacy toward Saint Domingue, 1798–1801," Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 9, no. 1 (Winter 2011): 114–41; and Ronald Angelo Johnson, Diplomacy in Black and White: John Adams, Toussaint Louverture, and Their Atlantic World Alliance (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2014). |

| 3. | Compare Paulus, The Slaveholding Crisis, 23–24 and Johnson Diplomacy in Black and White, 58–67. |

| 4. | For other studies of the Haitian Revolution's impact on the United States see Ashli White, Encountering Revolution: Haiti and the Making of the Early Republic (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010) and James Alexander Dun, Dangerous Neighbors: Making the Haitian Revolution in Early America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016). |

| 5. | Although Paulus does not cite Julius S. Scott, "The Common Wind: Currents of Afro-American Communication in the Era of the Haitian Revolution" (PhD diss., Duke University, 1988) or Janet Polasky, Revolutions without Borders: The Call to Liberty in the Atlantic World (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015), both offer extended analysis of networks of communication among enslaved and free people throughout the Atlantic World. |

| 6. | Matthew J. Clavin, Toussaint Louverture and the American Civil War: The Promise and Peril of a Second Haitian Revolution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010). |

| 7. | Paulus's analysis would have been strengthened by considering the essays in Jesús F. de la Teja, ed., Tejano Leadership in Mexican and Revolutionary Texas (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2010). |

| 8. | Paulus suggests the planter elite lost power in the 1840s. This contradicts a recent account of how politically powerful southerners created an aggressive foreign policy of slavery. See Matthew Karp, This Vast Southern Empire: Slaveholders at the Helm of American Foreign Policy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016), reviewed in Southern Spaces at https://southernspaces.org/2018/slaveholding-empire-southerners-federal-authority-and-slave-power-abroad. |