Overview

Elena Conis examines competing narratives of DDT to find a more complicated story of local American values, beliefs, and ideas about health and environment in the history of this pesticide during and immediately after World War II.

Public Health in the US and Global South is a collection of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications examining the relationship between public health and specific geographies—both real and imagined—in and across the US and Global South. These essays raise questions about the origin, replication, and entrenchment of health disparities; the ways that race and gender shape and are shaped by health policy; and the inseparable connection between health justice and health advocacy. Selected from a competitive group of submissions, these pieces offer new perspectives on the multiple meanings of health, space, and the public in the US and Global South. The series editor for Public Health in the US and Global South is Mary E. Frederickson.

Introduction

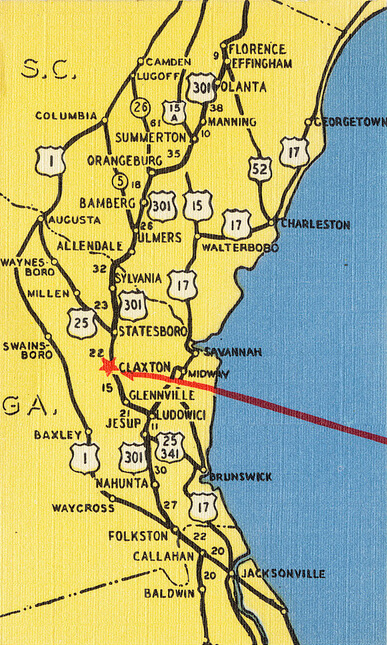

Early in 1949, Dottie Colson wrote to the National Health Council in New York City for advice on how to start a "real health movement" in her hometown. Colson believed that use of the pesticide DDT in her rural community outside of Claxton, Georgia, was causing grave harm, and that she and her neighbors had a right to be spared its effects. She described her own sensitivity to the chemical, her daughter's unyielding sore throat, the illness that had struck the family's dairy cows, and the loss of their baby chicks and honeybees. The harm to livestock, fowl, and bees, along with an endless stream of doctors' bills, threatened the family with financial ruin. In Colson's telling, DDT was destroying their lives.1Letter from Mrs. H.J. Colson to The National Health Council, January 31, 1949, Folder: T-47: Toxicology–Economic Poisons–Insecticides–Mrs. Plyler & Colson, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. More than that, as one of her neighbors put it, DDT was destroying a way of life, as it made small farms unsustainable and eroded the good health and cooperative spirit that were the backbone of rural communities such as theirs.2Letter from Mrs. B.C. Plyler to Hon. Herman Talmadge, August 17, 1950, Folder: Plyler and Colson, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives.

Colson's crusade against DDT began in 1945, the same year the pesticide emerged from the Second World War as an American miracle. First synthesized by an Austrian chemist in the late-nineteenth century, DDT's powers as a pesticide weren't discovered until World War II. By the time the war ended, it was credited with saving millions in Europe and the Pacific theater from insect-borne diseases, and the US Army proclaimed it the "war's greatest contribution to the future health of the world."3"DDT Seen for Public by Spring," Atlanta Journal, August 6, 1945, 18. Just a few months after the war's end in Europe, DDT became commercially available in the US. It was quickly and enthusiastically deployed in liquid and powder form against insect pests across the country, especially in the South, where health departments and agricultural interests hailed it as an authentically American "wonder drug" poised to bring the "magic" it had worked against diseases such as malaria and typhus abroad back home.4"Seminole Uses Wonder Drug to Fight Malaria," Atlanta Journal, March 13, 1945; "Danger – DDT," Georgia's Health 25, no. 4 (1945): 4.

But a countervailing narrative of DDT also emerged. Local media warned of DDT's potential to kill not only harmful insects but "the innocent and beneficial" as well, and to upset "the complex balance of nature."5"Use Care With DDT, Farmers Are Warned," Atlanta Journal, August 1, 1945, 12. At the same time, citizens like Colson and her neighbors circulated complaints about their personal encounters with the chemical and fought to keep it off their land and out of their homes. As they contacted state officials, local and federal lawmakers, and the pesticide manufacturers, they decried the widespread use of DDT as an infringement on their right to property and livelihood, an un-Christian cause of human suffering based on an irresponsible ignorance of the chemical's harm.

This essay recounts the story of one community's fight against DDT in the years immediately after its introduction to the US market, in order, first, to demonstrate that DDT's reception in this period was more troubled than the chemical's historiography generally allows, and, second, to insert a more complicated story of local American values, beliefs, and ideas about health and environment into the often-told global histories of DDT during and immediately after World War II. The pesticide's use in peacetime raised health and environmental concerns not urgent during wartime. In this new context, scientific knowledge about the chemical's range of effects appeared fragmentary and difficult to synthesize, and varying assessments of DDT's hazards to people and environments became challenging to reconcile. Conversations about the chemical and its use pointed up tensions between the assessment of risk in wartime and in peace; among professionals responsible for individual and public health; and between a lightly regulated industry and the government bodies charged with mitigating the consequences of its products' various uses. As these conversations took place, DDT acquired a layered symbolism: it remained a wartime miracle to most, even as to others it became the tool of a government in service to big-capital interests. Additionally, DDT's widespread, national visibility—fostered by wartime media attention and postwar advertising and promotion—was critical to the symbolism the pesticide acquired, and had paradoxical consequences for its reputation and, potentially, for its persistence on the US market in the decades after the war.

The Problem with Claxton

In the mid-1940s, Dottie Colson and her blacksmith husband Henry, along with daughters Hazel and Dorothy, lived on a small farm off newly paved Highway 280, which paralleled the railroad that ran from Savannah to Cordele. It was an ideal place to live; as Colson's neighbor—and sister—Mamie Ella Plyler put it, "No farm could be more conveniently situated, as we have paved highway outlets to all towns, are on Georgia Power line, mail delivery, telephone, [and] school bus and several passenger buses pass each way daily which take on or let off passengers at our door."6Letter from Mrs. B.C. Plyler to Prince Preston, September 7, 1950, Folder: T-47: Toxicology-Economic Poisons-Insecticides-Mrs. Plyler and Colson, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. This folder of letters contains evidence that other Claxton residents shared the sentiments and experiences documented by Colson and Plyler. This evidence includes a petition signed by a group of Claxton residents and pesticide surveys completed by residents. This essay draws predominantly on the letters written by Colson and Plyler, however, as their letters, in particular about a half-dozen very lengthy ones, contain the most detailed accounts of the community's experience. The bulk of these letters are in the records of the Department of Health; very few are in the records of the Department of Agriculture. The existing letters, however, indicate that the Claxton residents wrote to multiple government agencies, at all levels, across the state and in Washington, DC. But the stretch of highway outside of Claxton was not their first choice of residence. In 1942, the US Army had bought the land they then lived on, roughly forty miles southeast of Claxton, to expand Camp Stewart for an antiaircraft artillery training center and prisoner of war facilities.7A. M. De Quesada, A History of Georgia Forts: Georgia's Lonely Outposts (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2011), 107–109. Plyler later wrote that they moved with "chin up" in service of their country, even as the place they relocated to "took advantage of this forced exile of families" with inflated land prices that ultimately came with added costs.8Letter from Mrs. B.C. Plyler to Prince Preston September 7, 1950.

For Plyler, the problem with Claxton became apparent in March of 1945, when she fell ill. She later recorded that she had developed severe sores in her mouth and throat and a persistent "irritation" of the head that didn't give way until fall. Plyler's husband "B.C." and daughters Betty and Martha suffered similarly. Before long, she noted that their symptoms were seasonal: they set in when the "big land owners" who owned the fields surrounding her home began "spraying" their crops at the end of winter, and they let up when the spraying season ended in October. The sprays and dusts coated everything on the Plyler farm: cow pasture, vegetable garden, fruit trees, chicken coops, open feed boxes and water pans, clothes and bedding hung out on the line, and everything and everyone in the house if the windows were open when the spraying began. Moreover, the Plylers' chickens were dying, and their livestock were sick, too.9Ibid.

At first neither Plyler nor Colson knew what was being sprayed over the fields adjacent to their farms. But their suspicion quickly landed on DDT. During the war, DDT had earned fame for its ability to bring epidemics to a dramatic halt or prevent them entirely. It had saved war-torn Naples from typhus, soldiers in the Pacific from malaria, and troops in every theater from bed bugs, lice, and more.10Edmund Russell, War and Nature: Fighting Humans and Insects with Chemicals from World War I to Silent Spring (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 127–129, 155. National news outlets carried the word that the "magic insect powder" was "one of the greatest scientific discoveries" of the war and nothing short of a "miracle."11"DDT," Washington Post, August 1, 1945, 6; "DDT," Time, June 12, 1944; "Doubts DDT Caused Bay Fish Deaths," Washington Post, August 23, 1945, 3. In Plyler and Colson's home state, local papers echoed the message, calling DDT a "wonder insecticide" and the "Chemical That Saves Millions."12"DDT May End Malaria When War Needs End," Atlanta Constitution, May 13, 1945, 5B; Frank Carey, "Chemical That Saves Millions," Augusta Chronicle, December 4, 1944, 7.

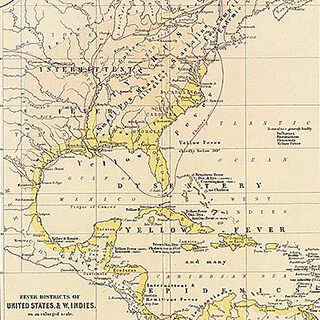

Colson and Plyler did not hear about DDT solely in dispatches from abroad. Before the war was over, DDT had been put to use in the Southeast's malaria belt, which included their home state.13Despite the fact that malaria rates were at historic lows in the early 1940s, the war had, according to historian Margaret Humphreys, brought new attention to the devastation wrought by the disease abroad, "and the crisis climate spread to the American South." Margaret Humphreys, Malaria: Poverty, Race, and Public Health in the United States (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 140. In 1942, the federal government had established the Malaria Control in War Areas (MCWA) agency, headquartered in Georgia and tasked with creating malaria-free zones around military sites. Two years later, the agency's head convinced Congress to authorize an expansion of their programming; the agency's "Extended Program" wouldn't focus solely on war areas, but on all malaria-prone areas across a dozen southern states. The program's main tool in rural areas was DDT, and in its first year, MCWA sprayed more than half a million homes. In Georgia, the health department boasted that only Arkansas had deployed more DDT.14"Mosquito Proofing," Georgia's Health 26, no. 8 (1946): 2; "Danger - DDT," Georgia's Health 25, no. 4 (1945): 4. The success helped inspire a second DDT-driven campaign in Georgia, against typhus; the state had among the highest rates of the disease in the nation.15The Department of Health's anti-typhus campaign was multi-pronged: it involved extermination, elimination of food sources, and rat-proofing of buildings. However, the dusting of rat runs with DDT took center stage in the department's dispatches about the effort. See for example, "DDT's Typhus Role," Georgia's Health 26, no. 8 (1946): 1; "Typhus Takes a Tumble," Georgia's Health 26, no. 5 (1948): 1; "5 Tons of DDT Received Here," Augusta Chronicle, November 21, 1945, 10; "Health Officers Will Spray DDT," Augusta Chronicle, December 2, 1945, 7. Soon, Georgia was also spraying and dusting rat "runs," municipal dumps, dairies, abattoirs, freezer-locker plants, sausage-manufacturing facilities, and more with DDT, all in a continued effort to eliminate the array of insects suspected of carrying infectious disease.16Communicable Disease Center Technical Development Division, Savannah, Georgia, "Summary of Activities," No. 12, October–December 1947, Headquarters and Branch Reports, Box 2, Record Group 442, The National Archives at Atlanta; Georgia Malaria Control in War Areas Carter Memorial Laboratory Savannah, "Summary of Activities," May 1945, Folder: MCWA Carter Memorial Lab; Savannah, GA 1946, 1945, Historical Files, Box 2, Record Group 442, National Archives at Atlanta.

Surviving health department records do not indicate that Claxton was among the towns where homes or businesses were sprayed as part of the Extended Program, although Claxton residents did record seeing DDT delivered to the local health office (and health officers' own letters confirm this). Surviving records of the state's Department of Agriculture document that Claxton and neighboring Evans County were sprayed with DDT sometime before the end of 1947, likely in an effort to control the white-fringed beetle, a nursery and crop pest.17Maps Index Cards, DDT Spray Program, March–November 1947, Record Group 13, Subgroup 2, Series 41, Box 1, Department of Agriculture, Georgia Archives; Hal Allen, "Air War Set in Macon Area on White-Fringed Beetle," Macon Telegraph, July 15, 1946, 1; "Battle against Beetle Mapped: Middle Georgia Counties Are Put under Quarantine," Macon Telegraph, Sept 25, 1946, 1. In the years after the war, DDT's uses rapidly evolved from predominantly public-health oriented to predominantly agricultural. In the wetlands and wildlife refuges to the east of Claxton, between Claxton and Savannah, the MCWA's Technical Development Branch laboratory (along with the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the US Department of Agriculture) carried out extensive tests on DDT's toxicity to animals in the wild and in the lab.18United States Public Health Service Malaria Control in War Areas Carter Memorial Laboratory, "Work Project Outlines," 1946, Headquarters and Branch Reports, Box 2, Record Group 442, National Archives at Atlanta; Summary of Activities No. 7, Communicable Disease Center Technical Development Division, Savannah, Georgia, July–September 1946, Headquarters and Branch Reports, Box 2, Record Group 442, National Archives at Atlanta. In the mid-1940s, then, Claxton residents would have been very familiar with both news and sight of DDT spread in and around their communities, whether as a dust or spray, by hand or by plane.

It was airplane application that proved so troubling to the residents of Claxton. As Pete Daniel describes in Toxic Drift, aerial pesticide application in the Deep South first began in the 1920s, when World War I aircraft were retrofitted with dispensers and cranks. Over the course of that decade, using planes to spread insecticides such as calcium arsenate and Paris green became more and more common on big cotton plantations.19Pete Daniel, Toxic Drift: Pesticides and Health in the Post-World War II South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press in association with Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, 2005), 48–50. Two decades later, the Second World War similarly—and further—propelled the practice as chemical warfare fogging tanks fitted to the bomb racks of fighter planes were filled with DDT emulsions and sprayed over southern Europe, North Africa, and Asia, sometimes dosing entire islands.20See for example Frank M. Snowden, The Conquest of Malaria: Italy, 1900–1962 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006), 199. After the war, some US farmers bought surplus planes, rigged them with spraying equipment, and coated their crops—sometimes with older pesticides, and sometimes with the new, synthetic ones developed for the war effort, including DDT.21Russell, War and Nature: Fighting Humans and Insects with Chemicals from World War I to Silent Spring, 162; "DDT Available for Civilian Use Early Next Week," Washington Post, July 27, 1945, 1. When Claxton residents saw rigged planes loading pesticides on Highway 280 (which the planes often used as a landing strip), and when they saw the planes flying low to coat the neighboring fields of tomatoes, peanuts, tobacco, and other crops owned by the "big land owners" who lived in town, they quickly concluded the planes were spreading DDT. They had no direct proof that the spray was DDT, but what else, as Plyler put it, could "come over like big clouds of billowy smoke from a locomotive, so dense it casts a shadow as it passes between us and the sun"?22Letter from Mrs. B.C. Plyler to Prince Preston, September 7, 1950.

In a petition sent to the director of Georgia's Department of Health, the governor, both Georgia senators, and their congressman, a dozen Claxton residents recalled a time "when all the dusting and spraying was done by the shaking of dusts by hand from a flour sack held over plants, or a hand operated sprayer, or an implement mule drawn." Such methods, they added, insured that the "insecticides stayed in the area they were being applied on." But in the new era of farming, they wrote, more and more farmers, especially the wealthier ones who lived in town and cultivated their hundreds of acres from afar, treated their fields using aerial crop dusters and sprayers. With "any breeze blowing," the sprays and dusts blew into small farmers' homes and onto their vegetables, pastures, chicken yards, and laundry lines. This practice, the residents argued, was causing "poisoning of humans" and "endangering life."23Petition submitted to Georgia Department of Public Health, October 24, 1950, Folder: T-47: Toxicology–Economic Poisons–Insecticides–Mrs. Plyler & Colson, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. And they were powerless to stop it.

The petition called on the health department to exercise its "authority" to restrict "the uses of, and methods of applying, insecticides in residential areas," based on the fact that the chemicals caused "distressing symptoms, acute suffering and even death in humans and other warm blooded farm animals and fowl."24Ibid. This last charge was not based on personal observations alone, although Colson and Plyler in particular listed such observations in great detail in years' worth of letters to state and federal officials. Rather, it relied just as much on the group's—and especially Colson's and Plyler's—dogged investigations into DDT and other "economic poisons" (as insecticides were called) of the postwar era.25Insecticides in the pre- and immediate postwar period were dubbed economic poisons for the fact that they were known poisonous substances used for economic benefit. The ubiquity of DDT in wartime and postwar news reports and advertising, along with its enthusiastic and widespread use in postwar state public health and agricultural programs, initially focused the Claxton residents' suspicion on DDT as a cause of their suffering. When they began to look into expert literature on the chemical more closely, they easily found evidence that appeared to prove it was harming their health—and they didn't have to dig very deep to find it.

Spraying interior of Italian houses with 10% DDT and kerosene for malaria control, 32nd Field Hospital, Unit B Installation, February 26, 1945. Image by Flickr user Otis Historical Archives National Museum of Health and Medicine. Creative Commons license CC BY 2.0.

Before drafting the petition with her neighbors, but after failed attempts to enlist the Department of Commerce, the Highway Patrol, and the Civic Aeronautics Administration to halt the aerial spraying of DDT on her land, Dottie Colson had reached out to Lester Petrie, the Director of Industrial Hygiene at the Georgia Department of Public Health.26Dottie Colson's first meeting with Lester Petrie is mentioned in a letter she wrote to him later, in the summer of 1948. Letter from Mrs. Henry J. Colson to Lester Petrie, June 30, 1948, Folder: T-47: Toxicology–Economic Poisons–Insecticides–Mrs. Plyler & Colson, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. I have found reference to contact with the transportation and trade agencies listed here, but I have not found the letters themselves. Colson hoped that Petrie could analyze samples of soil from her property, so that she could prove, once and for all, what had been sprayed on it—and what was making her sick. Her first letter to him betrayed a clear sense of frustration, as well as the assumption that despite DDT's reputation as a "wonder drug," it and the other economic poisons were not being sprayed for her health, but were certainly harming it. "I have tried to be very nice to all who are interested in using these poisons in an effort to save crops," she told Petrie, "yet when I find they are affecting the health of myself and my family, I feel I am justified in wanting to know more about them.27Letter from Mrs. H.J. Colson to Lester Petrie June 30 1948, Folder: T-47: Toxicology–Economic Poisons–Insecticides–Mrs. Plyler & Colson, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives.

In ensuing correspondence, Petrie shared department bulletins and press releases with Colson, and Colson, in turn, shared state laws and information she collected from scientific journals, private physicians, insecticide manufacturers, and "reliable farm papers."28Letter from Mrs. H.J. Colson to Dr. G.D. Lunsford, July 12, 1948, Folder: T-47: Toxicology–Economic Poisons–Insecticides–Mrs. Plyler & Colson, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. Petrie engaged in an ongoing pursuit of detailed information on the toxicity of the new economic poisons, DDT included, as evidenced by the countless letters he wrote to manufacturers and federal scientists asking for safety data. Despite this shared cause, however, Petrie very quickly reached the limits of his patience with Colson's demands—not only for information, but for antidotes, investigations, and state enforcement of safer spraying practices. To Colson, it was the health department's duty to protect the health of every Georgia resident. To Petrie, his duty was to preserve the health of the state by encouraging practices and policies based on the most recent scientific evidence. And there simply was no evidence of a threat to the state's health.

However, in the case of individual complaints about the newer economic poisons, Petrie found himself vexed. The chemicals' rapid commercial release after the war and the confidential nature of their wartime development meant that he had limited access to information about their safety and use; moreover, most of the information he did have access to, on DDT in particular, reflected the health and safety standards of military, not civilian use. He certainly had no antidotes, and he had only limited powers of enforcement over insecticide use.29These were provided in the "Economic Poisons Act," adopted in 1950 to regulate the sale, distribution, and transportation of new insecticides and application devices and enforced by the Department of Agriculture. He did have the power to investigate health threats, but aside from the Claxton complaints, no evidence suggested anything to investigate. Neither wartime research nor DDT's extensive use in the campaigns against malaria and typhus in Georgia had indicated any harm to health. The sole evidence comprised a series of case reports of DDT poisonings and deaths published across a range of US and European medical journals and all attributed to extraordinarily high doses of the insecticide. In one report, a group of starving war prisoners mistook DDT for flour and baked bread with it; those who ate the most bread suffered lasting neurological damage, but all survived.30Richard M. Garrett, "Toxicity of DDT for Man," Journal of the Medical Association of Alabama 17, no. 2 (1947): 74-76. Petrie could find no specific evidence that an incidental, ongoing, exposure like that faced by the residents of Claxton should cause any individual harm—even as Colson and Plyler assured him that the many physicians they consulted were sure that insecticides were behind their ill health.

"I have a great deal of sympathy for Mrs. Colson because of her alleged problems with regard to the killing of her bees, her personal hypersensitiveness to some of the dusts," Petrie wrote to a colleague in Washington, DC, but he found it suspicious that the "only" other complaint about DDT came from her sister.31See for example Letter from Lester Petrie to H.N. Graning, March 4, 1949, Folder: T-47: Toxicology–Economic Poisons–Insecticides–Mrs. Plyler & Colson, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. Department of Health files indicate that this was not true. To Petrie, the Claxton health problems were "all in their own minds."32Letter from Dr. L. Petrie to Dr. G.G. Lunsford, August 19, 1948, Folder: T-47: Toxicology–Economic Poisons–Insecticides–Mrs. Plyler & Colson Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. Over and over, state officials dismissed Colson's and her neighbors' claims about DDT and other insecticides. And yet the complaints the Claxton residents made echoed the DDT cautions and warnings expressed in news coverage of the chemical, and throughout government and scientific reports, documents, and publications on DDT. As one news clipping service noted, "not a few" of the tens of thousands of DDT-related articles published just after the war "cautioned the public against its sinister and unknown dangers."33H.H. Stage, "Facts and Fallacies About DDT," Mosquito News 6, no. 1 (1946): 1. Many of these admonitions came from official sources and carried the message that DDT was a toxic chemical potentially destructive of nature and harmful to humans.

"Double-Edged Sword"

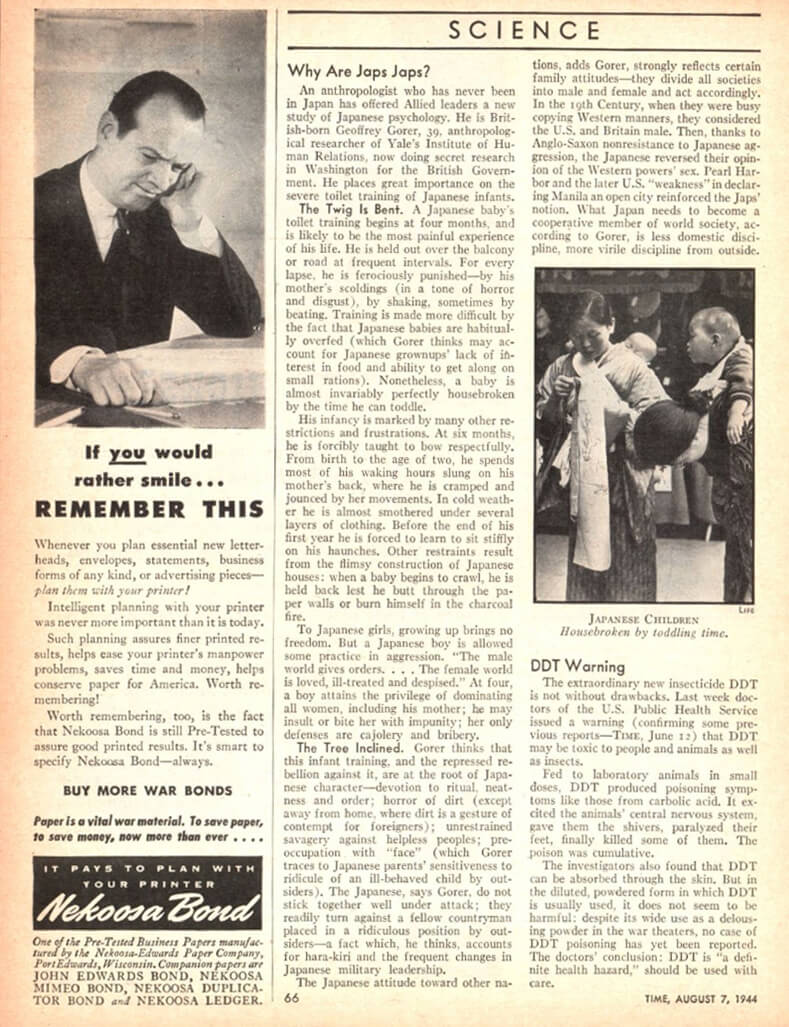

DDT Warning, August 7, 1944. Scan by Time magazine archive. Originally published in the August 7, 1944, issue of Time magazine, page 66.

Such concerns were not hidden. When the Washington Post announced, on its front page, the US Army War Production Board's decision to allow the sale of surplus DDT to civilians in 1945, the article's first sentence informed readers that the Board "warned against 'use of it to upset the balance of nature.'"34"DDT Available for Civilian Use Early Next Week," Washington Post, 1. The second sentence spoke of hazards to users and risks associated with DDT residues on products (even as the article then went on to promise the chemical's future use in paints, plaster, and construction materials to make homes insect-proof). A month after Time magazine enumerated DDT's "amazing" properties, it ran an article, "DDT Warning," describing the "poisoning symptoms" produced in laboratory animals in "small doses"—shivers, paralysis, and occasionally death—along with evidence that the poison was "cumulative." DDT, the article concluded, "is 'a definite health hazard.'"35"DDT Warning," Time, August 7, 1944. The "double-edged sword" served as a popular metaphor for DDT, a weapon that would "rid your home of mosquitoes, flies, and vermin, but the price may turn out to be high in human health and life."36Jane Stafford, "Insect War May Backfire," Science News Letter, August 5, 1944, 90; Bob Jones, "DDT: Handle with Care," Better Homes and Gardens, November 1945, 10.

Local coverage did not always mirror the national news outlets. The Atlanta Journal, Atlanta Constitution, and Augusta Chronicle openly discussed DDT's risks and benefits, but the Macon Telegraph did not report on DDT until it was used against the White Fringed Beetle. The Savannah Morning News largely limited its coverage to developments in DDT research at the local MCWA branch. Nonetheless, many of the cautionary themes found in national reporting appeared in local media, including the double-edged sword. An Augusta Chronicle editorial compared DDT to the atomic bomb, not to convey its impressive nature (as DDT ads often did), but to emphasize that it "kills the innocent and beneficial as well as the obnoxious…and kills a lot of things which we do not want to kill."37Editorial, "Use DDT Intelligently," Augusta Chronicle, August 24, 1945, 4. Other reports made DDT's threat to nature even clearer. News reports in Georgia and neighboring states warned that "a single concentrated application destroys birds"; "even dilute applications are dangerous to fish"; and that, since the pesticide might be killing Georgia's wrens, robins, and mocking birds, "perhaps it would be just as well to leave DDT on probation for a while."38"DDT Available for Home Use within 30 Days, Agencies Say," Atlanta Journal, August 22, 1945, 5; Editorial, "Poisoning the Birds," Atlanta Journal, November 14, 1946; "DDT and Fish," Augusta Chronicle (Reprint from The Columbia (S.C.) State), July 12, 1947, 4. Papers quoted the Tennessee Valley Authority's health director saying that DDT's "potentialities" to cause "biological imbalance are very considerable."39"DDT May End Malaria When War Needs End," Atlanta Constitution; "DDT Insecticide Destroys Pests," Augusta Chronicle, June 3, 1945, 5B.

Channing Cope, farm editor and columnist for the Atlanta Constitution, vividly captured ambivalence toward DDT's release. When he brought home his first containers of the poison, Cope spread an emulsion on his home's doors, windows, walls, cracks, and crevices; on the shoulders of his cat Dinty; the back of his pig Pinky; the throats and legs of his mules; and the walls of his milking barn. As a final test, he coated his Scotch terrier with DDT dust. The next morning he was convinced: DDT was a wonder, but it also frightened him. For "we must remember, too, that DDT will kill the bees and that means that it will kill the clover (which means, too, that it will kill off our livestock). It will destroy the fruit crops which are dependent on the bee for pollenization! It will kill of most of the flowers for the same reason and will wipe out many of our vegetables." It's a great "tool for our betterment," he concluded, but it "has the power to ruin us."40Channing Cope, "DDT Experiment Proves Successful," The Atlanta Constitution, August 29, 1945, 7. This was no minor warning from the great popularizer of the insidious kudzu vine. Derek H. Alderman, "Channing Cope and the Making of a Miracle Vine," Geographical Review 94, no. 2 (2004): 157–177.

Cope's worries about pollinators formed part of a common refrain about DDT. "Farmers, truck growers, and victory gardeners," advised a Georgia health department engineer, should "wait and see" what agricultural experts ultimately decided about DDT's "potential to destroy…bees and other pollen carriers," before using it on their own land.41Steed, "Play Safe with DDT," Atlanta Journal Magazine, November 4, 1945, 22–23. The state entomologist ran notices that DDT "might have a deadly effect on Georgia's bee industry."42"Use Care with DDT, Farmers Are Warned," Atlanta Journal, August 1, 1945. Atlanta papers reported complaints of Florida beekeepers about DDT spray programs—and that Georgia beekeepers were "disturbed" that "DDT kills bees as readily as roaches."43Steed, "Play Safe with DDT," Atlanta Journal Magazine, 22–23; "Macdill to Test DDT for Mosquitoes," Atlanta Journal, August 5, 1945, 12. Such warnings, crucial to Georgia agriculture, were far from buried: "DDT Kills Bees, Other Insects, Helpful to Man," ran an Augusta Chronicle front-page headline in August of 1945.44A.P., "DDT Kills Bees, Other Insects Helpful to Man," Augusta Chronicle, August 28, 1945, 1.

Another Atomic Bomb?, Chicago, Illinois, 1945. Cartoon by Carl Somdal. Originally published in Chicago Daily Tribune (August 24, 1945). Courtesy of Chicago Tribune Archives.

Writing to Petrie from her home in Claxton, Plyler said she had read that the Georgia Beekeepers Association's vice president attributed the death of his bees to insecticides sprayed on a field near his home.45Letter from Mrs. B.C. Plyler to Lester Petrie, December 4, 1950, Folder: T-47: Toxicology–Economic Poisons–Insecticides–Mrs. Plyler & Colson, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. The loss was bad enough, but Plyler also saw something more egregious embedded in DDT's harm to beneficial insects: a form of economic injustice. It simply wasn't right, in her view, "to kill one man's bees to make another man's peanuts."46Ibid. Colson didn't need proof from the papers to argue that the poisoning of bees had far-reaching implications. "Half" of her family's bees had died since the neighboring landowners began spraying DDT, and because of bees' dual roles as honey producers and pollinators, the Colsons' ability to make a living was compromised.47Letter from Mrs. H.J. Colson to Lester Petrie, June 30, 1948; Letter from Mrs. H.J. Colson to The National Health Council. Colson, too, saw something more egregious and injurious to livelihood in DDT's insect-killing powers. She had become certain, through her own illness, that "any poison strong enough to kill or damage honey bees is surely strong enough to affect people who are susceptible to such things."48Letter from Mrs. H.J. Colson to Lester Petrie, June 30, 1948. And, noted Plyler, "How about the honey after the insecticide was blown all over it? Somebody ate it."49Letter from Mrs. B.C. Plyler to Lester Petrie, December 4, 1950.

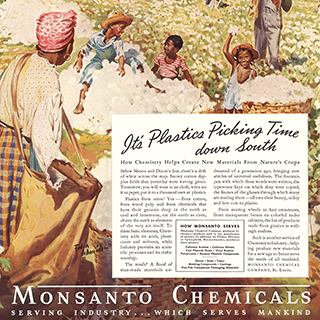

Federal DDT experiments conducted at the Savannah River Migratory Wildlife Refuge a few years earlier had focused expressly on the chemical's effects on bees (along with other insects, reptiles, and birds).50"Work Project Outlines 1946," United States Public Health Service Malaria Control in War Areas Carter Memorial Laboratory, Headquarters and Branch Reports, Box 2, Record Group 442, National Archives at Atlanta. Bees warranted special attention because they were, as one MCWA bulletin reflecting on the Extended Program put it, "so vitally concerned in the pollination of so many commercial crops."511944–45 Malaria Control in War Areas, Federal Security Agency, US Public Health Service, Headquarters and Branch Reports, Box 2, Record Group 442, National Archives at Atlanta. Even DDT-maker Monsanto expressed reservations about the chemical's "shadowy side"—meaning its detrimental effects on bees.52"Monsanto Makes DDT," Reprint from Monsanto Magazine, DDT, Vol. 1, September 1944, Folder: DDT Reports Vol 1 & 2, Box 3, Record Group 442, National Archives at Atlanta. Despite citizens' letters as well as government scientists' and manufacturers' acknowledgements of the problem, Georgia's health department responded with Machiavellian reassurances. To a Georgia man concerned about consuming honey in a region where cotton plants had been sprayed "following heavy poisoning schedules," Petrie replied that he had nothing to worry about—but not because the poisons weren't harmful.53Letter from Oscar E. Cole to State Department of Health, August 29, 1949, Folder: Toxicology – TEPP, DDT, ETC. Economic Poisons, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. The plants were likely sprayed with DDT or benzenehexachloride and sulphur, Petrie responded, and the DDT in particular was so toxic to honey bees that the bee feeding on such plants "does not even get back to the hive."54Letter from Lester Petrie to Oscar E. Cole, August 29, 1949, Folder: Toxicology – TEPP, DDT, ETC. Economic Poisons., Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. The public didn't have to worry about consuming the toxic spray carried by bees, that is, precisely because the spray's extreme toxicity to bees acted as a safety barrier protecting humans from consuming the same poison.

Such twisted reassurances had little effect on Colson and Plyler, both of whom saw themselves (and in Colson's case, her daughters) as uniquely susceptible to DDT-induced illness. From existing letters, it's unclear if this is how they felt from the start, or whether they developed this idea in response to official dismissals of their claims, or in response to what they read in the DDT-related literature they acquired. As local health director W.D. Lundquist put it, by 1949 they had amassed "volumes of articles, pamphlets and practically all information available on the subject of D.D.T.," likely giving them better access to information than he had.55Letter from Dr. W.D. Lundquist to Dr. L. Petrie, June 25, 1949, Folder T-47: Toxicology–Economic Poisons–Insecticides–Mrs. Plyler & Colson Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. When Lundquist met with Claxton residents and reviewed their collected materials, he found himself in the same information vacuum that posed such a problem for Petrie. He noted that while most of the articles and reports in Colson's and Plyler's possession stated that DDT was dangerous, and could be uniquely harmful to those who were sensitive, "none of them actually point out [specific] instances nor can I find what D.D.T. is supposed to do in the way of symptoms in the sensitive."56Ibid. The contents of Colson's and Plyler's collected materials can be reconstructed from their letters, and included articles from the Progressive Farmer, other farm papers, Georgia newspapers, pamphlets from manufacturers, government releases and bulletins, and journal articles.

The scientific literature contained frustratingly oblique references to individual variability in susceptibility to DDT: experiments demonstrated that the pesticide killed some rat ectoparasite species but not others, and studies on lab rodents had shown that individuals of the same species could be susceptible to DDT while others were not.57"Program Information," n.d. (1950–1953), Headquarters and Branch Reports, Box 3, Record Group 442, National Archives at Atlanta; Manuscript: Acute and Subacute Toxicity of DDT, June 21, 1944, Folder: Woodard, G., Nelson, AA., and Calvery, H.C., "Acute and Subacute Toxicity of DDT," A1 10, Box 12, Record Group 88, National Archives at College Park. Such studies offered little guidance to Lundquist and Petrie, precisely because they had emerged from a scientific paradigm developed to ensure the safety of industrial workers exposed to chemicals in high, ongoing workplace doses; their conclusions were a puzzle when applied "outside of the factory," as historian Linda Nash has observed.58Linda Lorraine Nash, "Purity and Danger: Historical Reflections on the Regulation of Environmental Pollutants," Environmental History 13, no. 4 (2008): 651–658. Industrial hygiene, or toxicological, experiments on animals sought to determine the chemical level a species safely "tolerated" without causing debilitating or permanent injury or death; they left no room for individual-level intolerance, apart from allergies. Evidence determined lethal doses and carcinogenic doses—not, necessarily, a chemical's more subtle or rare effects, which were of little interest to a profession responsible for ensuring workers' productivity.

Protection for Health and Property

In disbelief that government health workers could know so little about the chemicals that were their charge, Plyler pointed Lundquist and Petrie directly to literature from DDT makers that stated that "repeated exposure may without warning cause prolonged susceptibility to very small doses or exposures."59Letter from Mrs. B.C. Plyler to Dr. L. Petrie, December 14, 1950, Folder: T-47: Toxicology–Economic Poisons–Insecticides–Mrs. Plyler & Colson Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. Lundquist replied that he "sincerely believed" that insecticide dusts could irritate "some people," but his doubt that Claxton residents had received high enough doses to "poison" them reflected his allegiance to the tenets of industrial hygiene, a profession responsible for, but without answers to, the problem of the public's chemical exposures.60Letter from Dr. W.D. Lundquist to Dr. G.G. Lunsford, July 17, 1948, Folder: T-47: Toxicology–Economic Poisons–Insecticides–Mrs. Plyler & Colson Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. Instead, Lundquist and others resorted to character judgment—and misogyny. The health department's director of local operations, Guy Lunsford, attributed Colson and Plyler's symptoms to their "overanxious" nature and believed that Colson in particular was motivated by money, since she had reportedly spoken with a lawyer who suggested she had a winnable case.61Ibid. Lundquist nonetheless questioned all the local doctors he could find, in a quest to uncover and confirm other reports of "hypersensitive" individuals—but he found none.62Ibid. He wrote to Petrie in frustration in August 1948: "I wish that the State Department could have these cases tested for sensitivity to these chemicals so as to prove or disprove once and for all their claims and convictions."63Letter from Dr. W.D. Lundquist to Dr. L. Petrie, August 13, 1948, Folder: T-47: Toxicology–Economic Poisons–Insecticides–Mrs. Plyler & Colson Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. But such tests did not exist, and there was nothing in the literature, as the health experts saw it, to prove or disprove Colson's and Plyler's claims.

In fact, the lack of substantive and applicable evidence about the harmful effects of exposure to the new economic poisons was consuming a sizable portion of health department energy. Petrie may have dismissed Colson's and Plyler's claims in correspondence with his colleagues, but his files indicate that his division of the state health department was engaged in an ongoing, though often fruitless, campaign for clues and data about insecticide toxicity from other state health departments and from insecticide manufacturers themselves. He wrote to the US Army's Industrial Hygiene lab for help with the "problem of poisoning caused by organic insecticides," figuring that since so many of them were developed as war gas poisons the Army could share its experience "combating and investigating" them. (The organic insecticides included the organochlorines, such as DDT, and the organophosphates, which included parathion.) Petrie asked the USDA for every piece of information on labeling guidelines. He wrote to chemical companies, asking them to add tracers to their insecticides so state health officers could figure out which sprays were causing which illnesses—and which deaths. A response from Monsanto's medical director summed up the reason why the companies would never do this: it would cost too much.64Letter from R. Emmett Kelly to Dr. L. Petrie, August 4, 1950, Folder: Toxicology Economic Poisons-General-1951, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives.

Petrie also wrote to other state health departments to collect information on poisonings and related laws. The result was a collection of harrowing stories of insecticide poisonings that he kept in his files: the woman who died within hours after eating blackberries bordering a recently sprayed cotton field; the deaths of pilots who flew cotton-dusters; the tenant farmer found collapsed in a sprayed tobacco field; the ten-year-old boy who died after swigging from a whiskey bottle he found in the crotch of a tree, not knowing it contained pesticide; the two children who died after making mud pies with "fruit spray"; the six-year-old boy who died when "plant spray" spilled on his leg; and many others.65News clipping: "Spray Poison Kills Two Tots," March 17, 1954, Folder: Toxicology-General, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives; News clipping: "Poisonous Spray Kills Boy 6," n.d., Folder: Toxicology-General, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives.

The sprays in these cases were sometimes identified, sometimes not. Those most often responsible for the worst poisonings didn't contain DDT, but parathion and TEPP (tetraethyl pyrophosphate). The latter insecticides emerged, like DDT, from wartime research, but they belonged to a different class of far more acutely toxic chemicals; toxicity tests showed that a single drop of TEPP in the eye could be fatal. Spared the fanfare of DDT, their harms went largely unnoticed by the public—and appear to have been mapped onto DDT instead. When Petrie sent a safety bulletin to local health departments and county agents with detailed warnings about the "new insect sprays," the resulting local news stories carried headlines such as "Farmers Warned DDT is Harmful"—but rarely referred to the other insecticides by name.66News Clippings: "Economic Poisons Bulletin," November 1950, Folder: N-16: Newspaper Clippings-Insecticides, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. News items based on Petrie's bulletin ran in the Covington News, Quitman Free Press, Polk County Times, Millen News, Cobb County Times, Hawkinsville Dispatch and News, Jesup Sentinel, Dalton News, Early County News, Cedartown Standard, Morgan County News, Abbeville Chronicle, Daily Tifton Gazette, Carroll County Georgian, and elsewhere. When the other insecticides were mentioned, they often were described in comparison to DDT: one percent of parathion was described as more potent than a five percent DDT preparation; toxaphene was described as sixteen times as toxic as DDT.67News Clipping: "Despite Warnings of Government Agencies Deadlier Chemicals for Insecticides Are Released Each Year," Durham Herald, NC, October 20, 1949, Folder: N-16: Newspaper Clippings-Insecticides, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. As a household name, DDT became the touchstone for the new class of synthetic economic poisons, which had paradoxical implications for its reputation: the worst traits of more acutely toxic insecticides were projected onto it even as it was described as relatively safe among the new insecticides.

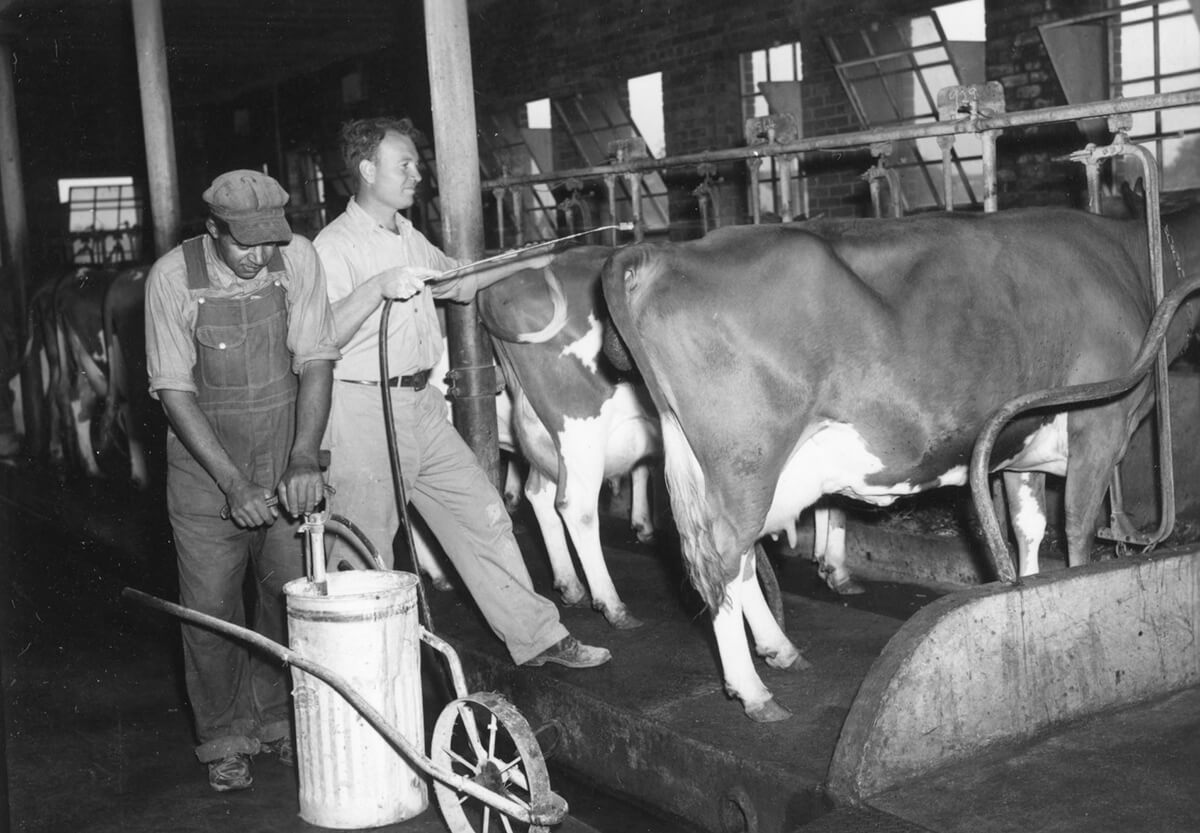

Petrie's preoccupation with the acutely poisonous organophosphate insecticides offered another reflection of the professional norms of industrial hygiene. The pesticides causing rapid onset of symptoms and death captured the attention of the state health department—especially since some had the capacity to be fatal in strikingly small doses. DDT caused few deaths, and while toxic to the nervous system, required a very large dose before symptoms of poisoning set in. Yet unlike the organophosphates, DDT accumulated in bodies, building up in fat tissue and leading to scientific concerns that its toxic effects compounded with accumulation. This property was known, and publicized, from early on: Time had notified readers in 1944 that DDT's "poisoning" properties were "cumulative."68"DDT Warning," Time. The Atlanta Journal Magazine, too, warned readers against getting DDT dust or solution on their hands precisely because the insecticide's toxic effects to humans "may be cumulative."69Steed, "Play Safe with DDT," 22–23. As studies of lab rodents and dogs had shown, DDT also was passed along in milk. Colson told Petrie these properties had her very worried. From what she read, she knew the farm's eggs and milk contained DDT.70Letter from Mrs. H.J. Colson to Lester Petrie, January 29, 1949, Folder: T-47: Toxicology–Economic Poisons–Insecticides–Mrs. Plyler & Colson, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. From what she experienced, she knew DDT had the capacity to cause illness, because of the days when insecticide blew into her sister's cow lot while her children milked. When they drank the milk, their mouths and throats "burned, hurt, and swelled."71Letter from Mrs. B.C. Plyler to R.H. Fetz, April 27, 1951, Folder: T-47: Toxicology–Economic Poisons–Insecticides–Mrs. Plyler & Colson, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives.

Representing the professional norms of industrial hygiene and employing the rationale of proven-benefits-to-the-many outweighing reported-risks-to-the-few, state health officials responded to Colson and Plyler. Regional medical director Lundquist said that he had had the opportunity to "closely observe the effects of DDT in five different counties" and had never heard of anyone saying that DDT made them sick. Spraying had occurred in fifty other Georgia counties, affecting "hundreds of thousands of people," commented Lundquist, and "several hundred men in the State" worked as sprayers, "who are thoroughly covered or soaked with the chemicals at the end of each day's operations."72Letter from Dr. W.D. Lundquist to Mr. G.O. Hohwer August 19, 1948, Folder: T-47: Toxicology–Economic Poisons–Insecticides–Mrs. Plyler & Colson, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. If DDT hadn't made them sick, it couldn't make anyone sick. Petrie, to prove the same point, sent Colson an article from the Journal of the American Medical Association describing the hundreds of thousands of lives saved when the US Army dusted the people of Naples in 1943. "There were no serious cases of impaired health," he told her, "nor any deaths reported as being attributed to DDT as a result of this experience." The same message was conveyed in a Federal Security Agency release he shared with her, issued after a 1949 national scare about DDT in milk, which reminded Americans that DDT had "contributed materially to the general welfare of the world" without "ever" causing human sickness due to the DDT itself.73Federal Security Agency Public Health Service, Washington, DC Memorandum, April 1, 1949, Folder: T-47: Toxicology–Economic Poisons–Insecticides–Mrs. Plyler & Colson Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. Generally, federal documents on the pesticide, such as this one, attributed DDT-related illnesses to the solvents used to emulsify it, and not the DDT itself. Colson's and Plyler's assertions of individual risk were invalidated by state and even global benefit, and by the fact that so many people had withstood high-dose exposures seemingly without incident.

For Colson, however, there were a few problems with this reasoning. Population statistics and the experiences of spray operators that suggested DDT was safe meant nothing in the case where someone was uniquely sensitive to the chemical—as Colson believed she and her daughters were. "It is unfortunate indeed," Colson told Petrie, "to be one of the proven few that DDT is so very poisonous to."74Letter from Mrs. H.J. Colson to Lester Petrie, January 29, 1949. Without directly articulating it, she expressed a sentiment then circulating among experts discussing DDT's widespread use after the war: as the chemical's deployment shifted from military to civilian use, its benefits and risks needed weighing anew, but all too often, this calculation was not done.75Russell, War and Nature: Fighting Humans and Insects with Chemicals from World War I to Silent Spring, 158–164. Risks tolerable in wartime were often intolerable in times of peace, and she counted her own insecticide sensitivity among the latter. Moreover, as one of the "few," Colson felt she was being asked to sacrifice her health for the convenience and wealth of others. She and her family had readily given up their former home and moved to Claxton to make room for Camp Stewart's expansion. But by failing to stop the spread of insecticides over her land, her government, she felt, was remiss in its duty to guarantee all a "reasonable amount of protection for health and property," she wrote. "I believe the Constitution gives us this much."76Letter from Mrs. H.J. Colson to Mr. J.G. Townsend, August 20, 1949, Folder: T-47: Toxicology–Economic Poisons–Insecticides–Mrs. Plyler & Colson, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives.

Plyler, meanwhile, voiced an additional objection to health department dismissals. In years of protest against DDT, she had consulted with countless doctors, written to agencies in Washington, visited with representatives of chemical companies, and interviewed people all over southeastern Georgia.77Letter from Mrs. B.C. Plyler to Prince Preston, September 7, 1950. Her inquiries turned up plenty of stories of DDT skepticism and harm: to the boy who died from eating sprayed berries; the pastor and the farmer whose cows were killed; the cotton farmer who refused to use it anymore; the merchants who said insecticides made them sick; and the war veteran who told her that DDT "might not have hurt the guy putting it out but sure hurt the ones who had to live in it."78Memorandum, Evans County, by Guy G. Lunsford, n.d., Folder: T-47: Toxicology–Economic Poisons–Insecticides–Mrs. Plyler & Colson, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives; Letter from Mrs. B.C. Plyler to Lester Petrie, December 4, 1950. Not every story Plyler cited contained a clear reference to DDT, but DDT was the only chemical mentioned by name in any story. Not every story Plyler collected contained a clear reference to DDT, but it was the sole insecticide she mentioned by name. She came to doubt the assertion that hundreds of thousands of people had been exposed to DDT "without having registered any complaint."79Ibid. Instead, she believed their complaints simply hadn't been registered.

A Form of Economic Injustice

Over the course of their five years of letter writing, Plyler became increasingly invested in publicizing not just the harms of DDT, but the tragedy of postwar shifts in the economy and governance that her fight against the chemical had revealed. The economic poisons may have protected crops, but this agricultural advantage came at a significant cost to the health of livestock and people. When a small land owner felt this effect, she argued, he abandoned the hazardous substances. The "big land owner," by contrast, lived in town, never felt the effects and shielded himself from insecticide-related losses. "He sends out a crop dusting plane…he doesn't even risk a mule in it. If his mule got sick or died, he would be the loser, but if the negro or poor white man is made sick" he never has to pay the bill. Georgia, it was clear to her, had three classes—"the rich man, his hands, and the little land owner"—and only the first of these stood to survive. The others would "soon be extinguished if they and all their possessions are covered with insecticides beginning in March and continuing into October every year."80Letter from Mrs. B.C. Plyler to Lester Petrie, December 4, 1950. Plyler hoped someday to tell this story in a series of articles for national publication. She had already decided on a title: "This Is Georgia."81Letter from Mrs. B.C. Plyler to Prince Preston, September 7, 1950. I have no evidence that Plyler wrote professionally, but according to the 1940 census, she completed two years of high school. Her activism—and that of her sister—may be a function of their Southern Methodist upbringing: ancestry records accessible online suggest that their paternal grandfather was married in the Sand Hill Methodist Church in Tattnall, GA. On Southern Methodist women's tradition of involvement in social reform movements, see Paul Harvey, Freedom's Coming: Religious Culture and the Shaping of the South from the Civil War through the Civil Rights Era (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 75–77; Samuel S. Hill and Charles H. Lippy, Encyclopedia of Religion in the South (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2005), 845.

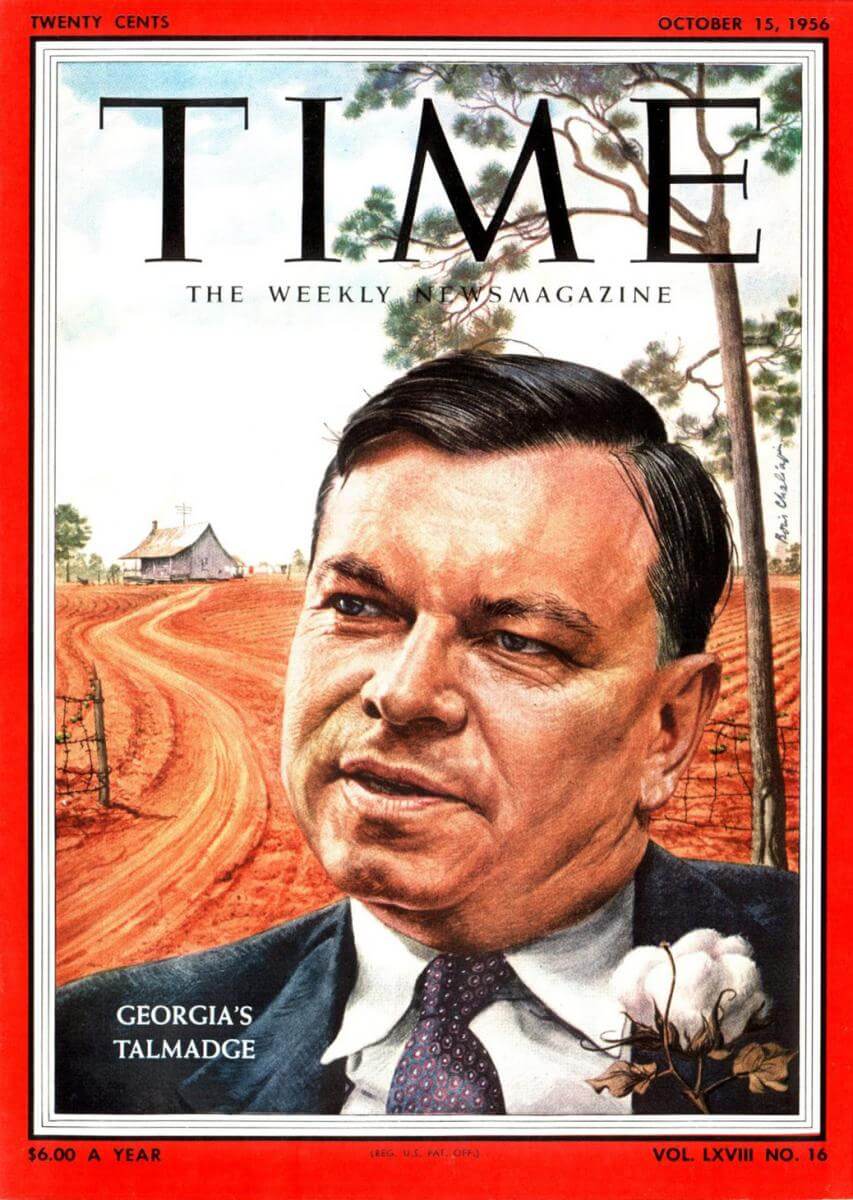

In a letter to Georgia governor Herman Talmadge in 1950, Plyler wrote that her battle against DDT had convinced her that her government had abandoned its "Christian" duty to its citizens. Families were being "herded out of God's open country"—in her case, first to serve the war effort, and now to suit big landowners. She described a cooperative way of life that existed only on small farms, and that depended on conditions that allowed parents, children, cows, pigs, chickens, and vegetable and flower gardens to thrive. Agents of the state had abetted big landowners in eliminating the "happy experiences of comradeship from which many of the fundamentals needed in the making of happy, useful citizens have their beginning," she told Governor Talmadge. "Can we hope to enjoy good health in Georgia and have this happiest opportunity?" she asked. Or must we "be poisoned to death in our own homes?"82Letter from Mrs. B.C. Plyler to Hon. Herman Talmadge, August 17, 1950. Underline in original.

Plyler's letter spoke to larger changes. Drawn by abundant natural resources and state governments promising low-wage and non-unionized labor and cheap (or free) land, military installations sprang up and expanded, and a host of industrial operations migrated into the South.83James C. Cobb, Selling of the South: The Southern Crusade for Industrial Development, 1936–90 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1993). Rural population declined while the farms that remained grew larger.84Christopher J. Bosso, Pesticides and Politics: The Life Cycle of a Public Issue (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1987), 23. The new economic poisons accelerated the shift to monoculture farms, a trend that came with the promise that industrial agriculture was the best way to feed the nation—and the world.85Ibid., 26–30. Plyler longed for a sense of neighborliness that she felt was the hallmark of small farms. As Christopher Bosso notes, pre-war biological pest control depended upon a cooperative ethos among farmers and an "active government role." In the postwar era, chemical pest control favored a farmer's "individualized mastery of his particular chunk of nature, a mastery requiring little, if any, government meddling."86Ibid., 32. By spraying, each farmer had no need to think beyond the borders of his or her own land. Plyler perceived a flaw in this logic: as new chemicals promised benefits for the many, they introduced threats into the shared physical environment in a cultural setting which exhorted everyone to think only of themselves. Plyler hoped for a government that would act as a check on these transformations, as there was no law or regulation protecting individuals from sprays that drifted, unwanted, onto their own land. When Congress passed the Federal Insecticide Fungicide and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) in 1947, however, it simply placed government in the role, as Bosso has put it, of "authoriz[ing] the manufacture, sale, and use of products carrying potential hazards to the public health and environment."87Ibid., xii. Plyler certainly would have agreed with the characterization that DDT poisoned people in their own homes and that government sanctioned the practice instead of stopping it.

Not all the "billowing clouds" blowing over the small farms of Claxton were DDT. By the time Plyler wrote her plea to Governor Talmadge, she and her neighbors had confirmed that neighboring property owners were using DDT—but they were also using pesticides containing parathion, copper, and arsenic. Plyler's most recent doctor's visit had led to a diagnosis of arsenic poisoning.88The Claxton residents had found a label from an insecticide container that a local merchant claimed to have sold to the "big land owners;" it contained 20% DDT, but the merchant also reported selling the owners other sprays, too. Letter from Mrs. B.C. Plyler to Prince Preston, September 7, 1950. The health department responded to the diagnosis by launching an investigation involving clinical and laboratory testing—something the Claxton residents had requested all along. Petrie's office sampled well water and urine, testing parents, children, and neighbors. The tests came back negative.

Later in that fall of 1950, Colson experienced her old symptoms on a visit to the Claxton health office, and a neighbor told her that she had seen a leaking container of DDT and chlordane—another new economic poison (and relative of DDT)—on the office's back porch. Colson's conviction that DDT was at the root of her community's problems returned. So did Plyler's, after a similar experience visiting a shop in a nearby town. Their conviction was about more than symptoms. To the Claxton residents, DDT was not just a health threat, but a symbol of a changed nation, a distant entity that did not have their small-farming community's best interests in mind, cared nothing for the sacrifices it had made during the war, and now prioritized big-capital interests over those of hardworking citizens, in the process destroying a way of life.

An Unexplored Archive

Early in 1945, before DDT had become available to the American public, The Saturday Evening Post ran an article on its discovery, battle victories, and inherent dangers, written by Brigadier General James Stevens Simmons, chief of preventive medicine for the US Army. It was Simmons who called DDT "the War's greatest contribution to the future health of the world," and while he wrote that its myriad possible benefits were "sufficient to stir the most sluggish imagination," he also described the chemical's "alarming" toxicity and its potential to "disturb vital balances in the animal and plant kingdoms."89James Stevens Simmons, "How Magic Is DDT?," Saturday Evening Post, January 1, 1945, 18–20. Despite its tempered tone, Simmons' article has been cited repeatedly by historians, as well as other scholars and writers, as evidence of the American public's wholehearted reception of DDT as the US emerged from the war—and for the better part of the two decades that followed.90See for example James Whorton, Before Silent Spring: Pesticides and Public Health in Pre-DDT America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1974), 248; Russell, War and Nature, 124; Thomas Dunlap, DDT, Silent Spring, and the Rise of Environmentalism (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008); Will Allen, The War on Bugs (White River Junction, VT.: Chelsea Green Publisting, 2008), 171. As historian William Cronon has written, "Until 1962"—the year Rachel Carson's pesticide exposé Silent Spring was published—"Americans were far more inclined to regard DDT as a miracle than as a menace."91Dunlap, DDT, Silent Spring, and the Rise of Environmentalism, x.

Several historians who have studied DDT's story in depth, including Thomas Dunlap, Edmund Russell, and David Kinkela, acknowledge the ambivalence of Simmons's account.92Russell, War and Nature, 125; Dunlap, DDT, Silent Spring, and the Rise of Environmentalism, x; David Kinkela, DDT and the American Century: Global Health, Environmental Politics, and the Pesticide That Changed the World (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 31. And yet, the historiographic conclusion that has emerged from analyses of DDT discourse in the postwar years is that early DDT cautions and warnings were quickly abandoned in light of the pesticide's promise as a tool of technological modernization in the context of postwar exuberance.93Kinkela, DDT and the American Century, 7. Dunlap claims that for a decade after DDT came on the commercial market, "only two groups paid much attention to it: the economic entomologists who recommended sprays and the public health officials who regulated residues on food."94Dunlap, DDT, Silent Spring, and the Rise of Environmentalism, 29. And Russell argues that debates among experts about how best to weigh the benefits and risks of DDT as it moved from military to civilian use were hidden from view of the public.95Russell, War and Nature, 158–164.

The letters written by the residents of Claxton, Georgia, suggest that this was not the case. There's no doubting the enthusiasm displayed for DDT immediately after the war, when headlines called it "dynamite" and "magic"; popular writers dreamed of a day without "roaches in the cupboard" and "ants in the sugar"; and drugstores sold out of their stock before the chemical even arrived.96John K. Terres, "Dynamite in DDT," New Republic, March 25, 1946, 415–416; Simmons, "How Magic Is DDT?."; Truman McMahan, "DDT," Colorado County Citizen (TX), September 27, 1945; "Small Amount of DDT Put on Sale Here," Washington Post, August 18, 1945, 2. But cautiousness and circumspection abounded, too. Warnings about the risks DDT posed to humans, animals, and nature appeared repeatedly and prominently in the national and local press. Although historian James Whorton, among others, has argued that early warnings about DDT were "generally dismissed as hysteria," when the historical record broadens beyond expert and institutional sources, it does not uniformly support this view.97Whorton, Before Silent Spring, 250. A notable fraction of reporters, county agents, and farmers took early warnings seriously. And the letters of Claxton residents indicate that warnings were within easy reach of the self-described "housewife" of a blacksmith, the "housewife" of a small farmer, and their neighbors in a locale with direct exposure to DDT.

Black Flag Insect Killer advertisement from the June 19, 1950 issue of Life magazine. Scan by Flickr user clotho98. Creative Commons license CC BY-NC 2.0.

The Claxton letters may turn out to be unique. They may also turn out to be the tip of an unexplored archive. Colson, Plyler, and their neighbors did not (as far as I have found) publish letters to the editor in local or national papers. The extant record of their correspondence with state and federal health and agricultural officials and politicians is also fragmentary. But its existence indicates that the experience of individuals who encountered DDT may shift historical thinking about the chemical's storied dramatic change of fortune between the mid 1940s and the late 1960s. It also indicates that it's worth looking for and at more obscure sources yet to find the voices of spray operators, farm hands, migrant agricultural workers, merchants, and small farmers like the Colson and Plyler families, who may have received DDT, and its class of postwar chemicals, with as much ambivalence and precaution as many privileged experts did, if not more. Lastly, this record supports—and sheds light on—otherwise offhand references to popular resistance to DDT spraying operations in government and other expert sources. MCWA records of the Extended Program of malaria eradication, for instance, mention "occasional refusals to having houses sprayed" in South Carolina and Arkansas.98See for example Malaria Control in War Areas, Federal Security Agency, US Public Health Service. They say nothing of refusals in North Carolina, even though that state's health journal reported that some householders were "dubious" of DDT spray teams and that ten percent of homes turned away the teams on their first visit.99Jens A. Jensen, "The DDT Residual Spraying Program for Malaria Control in North Carolina," The Health Bulletin 60, no. 10 (1945): 12–14. Opposition to DDT existed from the start, but its extent, contours, and meanings as yet remain unexamined.

In part, this open question remains because much of the historiography of DDT assumes what experts in the 1940s (and some historians of later decades) assumed: that early objections to DDT represented "hysteria," a word itself suggesting dismissal of DDT objections because of the identity of the individuals voicing them. Colson and Plyler were accused of being "overanxious," and the DDT problems they perceived "all in their minds," even as male newspaper columnists, county agents, beekeeper association heads, and scientific authors who raised identical concerns were not similarly accused. Of course, Colson and Plyler's DDT critique went further than theirs. Many of DDT's critics worried that the insecticide could adversely affect health and nature; Colson and Plyler expressed certainty that it did. They also tied the chemical's use, and the laws and regulations supporting its use, to larger problems they perceived in the postwar political and economic order. For this, they faced gendered character attacks. Their experience presaged the orchestrated opposition that Rachel Carson encountered after the publication of Silent Spring, and that other female activists striving to draw a connection between environmental contaminants and human ill health faced in the decades that followed.100Linda J. Lear, Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature, 1st ed. (New York: H. Holt, 1997), 430; Elizabeth D. Blum, Love Canal Revisited: Race, Class, and Gender in Environmental Activism (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2008), 54–55.

Colson and Plyler were literate, educated, and empowered enough to voice their objections to DDT and all that it symbolized to them. They were also white. Well before DDT drifted over their homes, however, it was sprayed inside the homes of black families in rural Georgia and Arkansas' cotton country and in a village of sugarcane laborers in Puerto Rico. The spraying was part of a set of federal experiments (for which little record seems to exist) upon which broader use of DDT in the war and afterward was based. An article on the Arkansas experiments describes the "field site" as a place where "ninety-five percent of the houses are of tenant or sharecropper type, shotgun-construction, newspaper lined, and inhabited by Negroes making only a marginal living."101"DDT May Control Malaria," Science News Letter, December 30, 1944, 418. A report on the Georgia experiments notes that DDT left "negligible" markings on the walls, in homes that were so "crowded" with furniture and belongings it was difficult to spray.102Letter from S.W. Simmons to Porter A. Stephens, DDT Reports, Vol. 1, July 4, 1944, Folder: DDT Reports Vol. 1 & 2, Historical Files, Box 3, Record Group 442, National Archives at Atlanta. The decision to test the spray in their homes was undoubtedly supported by the observation that in the South, blacks had a higher prevalence of malaria than whites—not that justifications were needed in a time when blacks were routinely experimented on without consent. This differential value of lives troubled Plyler about the use of DDT after the war, when landowners subjected poor and black hands to the spray but wouldn't "risk a mule" in it. And this differential makes it all the more important to seek new sources on the nation's response to DDT during and after the war.

The second time North Carolina's spray teams passed through the communities targeted by the MCWA's Extended Program, just one percent of homes turned them away. Margaret Humphreys, in her study of malaria in the South, takes this as evidence of overwhelming popular acceptance of DDT, and as an indication that DDT's effectiveness put a shine on its reputation and paved the pesticide's way.103Humphreys, Malaria, 148. Passing references to resistance in the historical record often get read this way, as nothing more than proof that the American public happily doused itself in DDT in exchange for a pest-free existence. But lay resistance to DDT, even if official sources suggest it affected "just" one percent of the population, is worth further examination for two reasons. First, resistance may not have been as minor as recorded. Even if DDT doubters comprised a minority of Americans, such small numbers may belie important differentials along lines of race, income-level, gender, or occupation. Experiences of illness through chemical exposure eroded Colson's and Plyler's acceptance of DDT, but so did their feelings of frustration over what they perceived as a new relationship between citizen wealth and power and the government's failure to check imbalances in that power in the postwar years. Small numbers also say little to nothing about how acceptance took root across lines of race, class, and other factors, and whether it was secured not solely through jingoism and faith in technology, but through historically determined traditions of subservience to institutions of power. DDT's acceptance, of course, was built not just on its performance in war, but on the basis of the preliminary tests in "negro shacks" and plantation workers' homes.104Malaria Control in War Areas, Federal Security Agency, US Public Health Service; Letter from S.W. Simmons to Porter A. Stephens, DDT Reports, Vol. 1, July 4, 1944, Folder: DDT Reports, Vol. 1 & 2, Historical Files, Box 3, Record Group 442, National Archives at Atlanta.

Second, even if the opinions expressed in the Claxton letters (and embedded in the actions of people who turned DDT-wielding health officers away from their homes) represented a minority view, they retain value yet. For they offer insight into a transformative moment in American society, government, medicine, and public health—and insight into how that transformation was experienced in at least one corner of the South.105Historian Michael Willrich makes a similar argument about Progressive Era anti-vaccinationists in Michael Willrich, Pox: An American History (New York: Penguin Press, 2011). The Claxton residents' letters reveal a group of citizens disaffected by new patterns of wealth, the behavior of industry, and the growing distance of government, and frustrated by science's promises combined with lack of answers. Their push-back against technological developments, frustration with public health experts, and demand that government exercise greater authority to protect its citizens supports the argument that DDT debates of the 1940s presaged debates and events of the 1960s.106Russell makes the argument that expert debates about DDT did just this. See Chapter 8 in War and Nature: Fighting Humans and Insects with Chemicals from World War I to Silent Spring. Such sentiments formed a bridge between older forms of social activism and organized movements that led to the banning of DDT in the US later in the twentieth century.

Acknowledgments

Emory University's University Research Committee, the Chemical Heritage Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Emory University History Department supported the research and writing of this essay. The author thanks Carrie Crawford, Terrence Greer, Abigail Li Holst, Hays Hopkins, and Abigail Meert for invaluable research assistance and the anonymous reviewers for comments and suggestions.

About the Author

Elena Conis is a faculty member in the Graduate School of Journalism at the University of California, Berkeley and the Department of Anthropology, History, and Social Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco and author of Vaccine Nation: America's Changing Relationship with Immunization (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015). She is currently working on a book about the history of DDT.

Cover Image Attribution:

Fogging machine photograph courtesy of Flickr user Ken Hodge, ca. 1962. Creative Commons license CC BY 2.0.Recommended Resources

Text

Allen, Will. The War on Bugs. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2008.

Daniel, Pete. Toxic Drift: Pesticides and Health in the Post-World War II South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press in association with Smithsonian Institution, 2005.

Dunlap, Thomas. DDT, Silent Spring, and the Rise of Environmentalism. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008.

Kinkela, David. DDT and the American Century: Global Health, Environmental Politics, and the Pesticide That Changed the World. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Russell, Edmund. War and Nature: Fighting Humans and Insects with Chemicals from World War I to Silent Spring. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Whorton, James C. Before Silent Spring: Pesticides and Public Health in Pre-DDT America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1974.

Web

Charles, Dan. "How GMOs Cut the Use of Pesticides – and Perhaps Boosted it Again." NPR. September 1, 2016. http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2016/09/01/492091546/how-gmos-cut-the-use-of-pesticides-and-perhaps-boosted-them-again.

Cone, Marla. "Toxic Pesticide Banned after Decades of Use." Scientific American. August 18, 2010. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/toxic-pesticide-banned-after-decades-of-use/.

Conis, Elena, Michal Meyer, Bob Kenworthy, et al. "DDT: The Britney Spears of Chemicals." Audio Blog Post. Distillations. Chemical Heritage Foundation. February 2, 2016. https://www.chemheritage.org/distillations/podcast/ddt-the-britney-spears-of-chemicals.

Conis, Elena and Chemical Heritage Foundation Beckman Center. "#FellowFriday: Elena Conis." Storify. Accessed September 14, 2016. https://storify.com/ChemHeritage/fellowfriday-elena-conis.

"DDT—A Brief History and Status." US Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed September 14, 2016. https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/ddt-brief-history-and-status.

"Pesticide-Induced Disease Database." Beyond Pesticides. Accessed September 14, 2016. http://www.beyondpesticides.org/resources/pesticide-induced-diseases-database/overview.

"Southern Region." National Centers for Environmental Information. Accessed September 14, 2016. https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/rcsd/southern.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Letter from Mrs. H.J. Colson to The National Health Council, January 31, 1949, Folder: T-47: Toxicology–Economic Poisons–Insecticides–Mrs. Plyler & Colson, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Letter from Mrs. B.C. Plyler to Hon. Herman Talmadge, August 17, 1950, Folder: Plyler and Colson, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. |

| 3. | "DDT Seen for Public by Spring," Atlanta Journal, August 6, 1945, 18. |

| 4. | "Seminole Uses Wonder Drug to Fight Malaria," Atlanta Journal, March 13, 1945; "Danger – DDT," Georgia's Health 25, no. 4 (1945): 4. |

| 5. | "Use Care With DDT, Farmers Are Warned," Atlanta Journal, August 1, 1945, 12. |

| 6. | Letter from Mrs. B.C. Plyler to Prince Preston, September 7, 1950, Folder: T-47: Toxicology-Economic Poisons-Insecticides-Mrs. Plyler and Colson, Box 3, Record Group 26, Subgroup 4, Series 21, Georgia Archives. This folder of letters contains evidence that other Claxton residents shared the sentiments and experiences documented by Colson and Plyler. This evidence includes a petition signed by a group of Claxton residents and pesticide surveys completed by residents. This essay draws predominantly on the letters written by Colson and Plyler, however, as their letters, in particular about a half-dozen very lengthy ones, contain the most detailed accounts of the community's experience. The bulk of these letters are in the records of the Department of Health; very few are in the records of the Department of Agriculture. The existing letters, however, indicate that the Claxton residents wrote to multiple government agencies, at all levels, across the state and in Washington, DC. |

| 7. | A. M. De Quesada, A History of Georgia Forts: Georgia's Lonely Outposts (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2011), 107–109. |

| 8. | Letter from Mrs. B.C. Plyler to Prince Preston September 7, 1950. |

| 9. | Ibid. |