Overview

Tom Rankin reviews Martin A. Berger's Freedom Now! Forgotten Photographs of the Civil Rights Struggle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013).

Review

I remember well seeing Charles Moore's fire hose photographs from Birmingham in my hometown newspaper, the Louisville Courier-Journal. Six-years old in 1963, I had little understanding of the day's news, but it was impossible not to notice the violent spray of water knocking and pinning down black protesters. How could water and firemen be so harsh? A week or so later I probably saw the same photograph again, this time as a spread in Life magazine, the only mail I eagerly awaited and poured over, admittedly just for the photographs. No image became more iconic, no place more marked by photographs than Birmingham in the days of Bull Connor's hoses and dogs. Martin A. Berger's fine book, Freedom Now! Forgotten Photographs of the Civil Rights Struggle revisits those canonical images with compelling interpretations while broadening and deepening our vision through a much fuller collection of imagery of the struggle.

Berger's book may be seen by some as a corrective to the narrow visual history of the civil rights movement. If not a corrective, Berger has certainly offered an important augmentation, one that is essential in understanding the movement from multiple perspectives, including the life and nature of documentary news photography. As he argues so effectively in his "Introduction: The Case for a New Canon," our impressions of the movement are rooted in and defined by the perceived need of photographers and picture editors to "offer stark, morally unambiguous narratives" of injustice, images that might urge action. Additionally, many of those same image-makers and publishers were drawn to photographs that affirmed that whatever solutions to racial injustice might be persued, they "need not lead to social disorder," to quote Berger.1Martin Berger, Freedom Now! Forgotten Photographs of the Civil Rights Struggle (Berkley: University of California Press, 2013), 10. The images of the time often depicted activists as victims of white oppression—as often they were—conveying the message that the power and keys to change rested with interventions of white citizens.

The publishing of a particular photograph—for example, Charles Moore's "Firemen Use High-Pressure Hoses against Protesters, Birmingham, Alabama, May 3, 1963" (24–25)—could often lead to the reproduction of that same photograph in multiple places, over and over, year after year. This meant that while picture-makers expanded the view of the civil rights movement for daily readers through their decisive and determined work, over time some images that came to 'define' the movement, narrowed the perspective through their repeated publication. Berger's work interrogates the limitations of this visual history, and creatively and effectively introduces an expanded, more nuanced visual chronicle of the civil rights struggle. An image like Matt Herron's, "Fire Bomb Watch, Mileston, Mississippi, June 1, 1964" stands in sharp contrast to those that portray black activists as victims of white resistance. Quiet in tone and certainly not a hard news moment that front-page editors would reach for, this photograph suggests local black resistance, self reliance, and the ways in which people in Holmes County, Mississippi, guarded their essential and beloved community center. Throughout Freedom Now!, Berger provides revealing context of the 'place' of the photographs in the moment and in the history of the movement, interpreting what information rests within the frame of a given photograph and acknowledging that much of what we need to know to understand these images lies outside the frame. In Herron's Mileston image in the community center we, as viewers, are in the room, "protected by the vigilant pair."2Ibid, 74. Just as we must hear a diversity of voices to understand the movement in a particular place, we must see imagery beyond the narrow canon to fully appreciate the complexity of the time and the struggle. The combination of Berger's image selection and his carefully researched narrative does just that.

Just as we often take the same picture over and over, we also frequently see in our mind's eye a single historical frame that is akin to the limitation of knowing a place only through a predictable selection of postcards on a drugstore display rack. What we are always challenged to discover is what Walker Percy has called a "sovereign vision," a view of the movement made up from an expanded and enriched collection of photographic expression.3Walker Percy, "The Loss of the Creature," in Message in a Bottle (New York: Picador, 1975), 46–63. "While all collections of photographs present a partial and subjective picture of their subjects," writes Berger, "they are not all equally flawed."4Berger, Freedom Now!, 14. Regardless of the veracity of a particular photograph depicting the factual and emotional truth of a moment, individual photographs are but fleeting slivers of time cropped from a vast historical narrative. This is even truer from the reflective and researched lens of history. Thus Berger's work builds out the image bank and lets the complexity of the visual record challenge simple assumptions about the civil rights movement, allowing the canonical imagery to encounter and sit in juxtaposition with revelatory photographs not often seen.

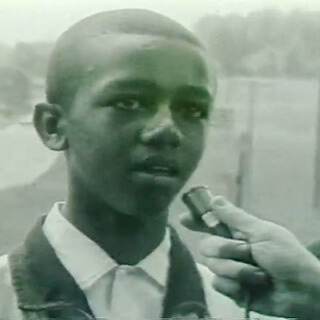

One of the most powerful and revealing of the 'new' images is, tellingly, from an unidentified photographer. "Women Resisting Arrest, Birmingham, Alabama, April 14, 1963" (96 and book cover) offers the opposite view of the black activist as victim of white authority. In this image the woman under arrest is doing all she can to wrestle free, including attempting to bite one of three policemen. Berger explains that this image was published in a best-selling segregationist pamphlet in an attempt to discredit the behavior of black activists. It was also published in Jet magazine where it questioned the unjust use of force on a woman while also applauding her stern resistance. The blurred motion in the image, perhaps a challenge for photojournalism editors at the time, communicates powerfully the moment's and the movement's violence and cacophony. That the photographer and the woman are unidentified reinforces the power of bringing such forgotten images into the public realm. Whatever converging reasons might have limited its publication in 1963 and the years following, the power and tenacity of "Woman Resisting Arrest" make it required viewing in any full visual history of the movement, seen within and alongside the familiar depictions of key events and known figures. This is the triumph of this book and the compelling argument of Berger's careful curatorial reimagining of how to view the civil rights struggle. Additional imagery will no doubt be recommended as complements to this stirring record, bearing additional witness to the power and nuance of the narratives revealed through the photographic evidence of the movement.

About the Author

Tom Rankin is professor of practice of art and documentary, director of the MFA program in experimental and documentary arts at Duke University. His books include Sacred Space: Photographs from the Mississippi Delta (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1993), Deaf Maggie Lee Sayre: Photographs of a River Life (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1995), Local Heroes Changing America: Indivisible (New York: W.W. Norton, 2000), and One Place: Paul Kwilecki and Four Decades of Photographs from Decatur County, Georgia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013) among others. Rankin writes frequently about photography and the documentary tradition and his photographs have been widely exhibited.

Recommended Resources

Text

Berger, Martin A. Seeing through Race: A Reinterpretation of Civil Rights Photography. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013.

Berger, Maurice. For All the World to See: Visual Culture and the Struggle for Civil Rights. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

Kelen, Leslie G. This Light of Ours: Activist Photographers of the Civil Rights Movement. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2012.

Percy, Walker. "The Loss of the Creature." In Message in a Bottle: How Queer Man Is, How Queer Language Is, and What One Has to Do With the Other, 46–63. New York: Picador, 1975.

Roberts, Gene and Hank Klibanoff. The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation. New York: Random House, 2006.

Web

Civil Rights 101: Civil Rights Chronology. The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. The Leadership Conference Education Fund. 2015. http://www.civilrights.org/resources/civilrights101/.

"For All the World to See: Visual Culture and the Struggle for Civil Rights." Center for Art, Design and Visual Culture, University of Maryland and Baltimore County, in partnership with the Smithsonian National Musuem of African American History and Culture, 2010–2013. Online Exhibition curated by Maurice Berger. http://www.umbc.edu/cadvc/foralltheworld/intro.php.

"Forgotten Photographs of the Civil Rights Struggle." The Daily Beast, January 20, 2014. http://www.thedailybeast.com/galleries/2014/01/20/forgotten-photographs-of-the-civil-rights-struggle.html.

"The civil rights movement in photos." CNN.com, April 8, 2014. http://www.cnn.com/2014/04/07/us/gallery/iconic-civil-rights.