Overview

Anne Mitchell Whisnant reviews Tammy Ingram's The Dixie Highway: Road Building and the Making of the Modern South, 1900–1930 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

Review

|

Tammy Ingram explores both more and less than the history of the Dixie Highway, built between 1915 and 1926 as a six-thousand-mile loop from Chicago and other Lake Michigan towns to Miami Beach and back. Dixie Highway foregrounds the political challenges in conceiving and creating an integrated, cross-country road in an era when the United States lacked a coordinated system of federal or state funding or planning for road building and when the affected states (especially in the South) had little to no bureaucratic, professional, or labor infrastructure to help plan, build, or manage such projects.

As a vehicle for examining America's transportation and modernization politics at a key moment of the country's rail-to-auto transition, the Dixie Highway project is quite useful. Passing through ten states on both sides of the Mason Dixon line, the highway invites comparison of how politics at the state level shaped transportation debates. Spanning the years during which the first federal aid highway acts were passed, a major war reshaped and reframed transportation needs, and automobile ownership surged, the Dixie Highway's story illuminates many of the planning, construction, and maintenance challenges of twentieth century highway network development.

Ingram opens with a discussion of the nation's chaotic transportation system at the dawn of the twentieth century, noting that until the advent of the automobile, roads and railroads coexisted uneasily. Railroads received considerable congressional investment and dominated long-distance and even regional travel and freight transit. Meanwhile, an anemic "spokes-on-a-wheel" system of ill-funded, mostly unimproved local-destination roads filled in the gaps from farm to railroad depot and enabled horse and wagon travel where railroads didn't go.

Ingram recounts how farmers and merchants chafed at the railroads' control over freight cost and time schedules and at the difficulties of navigating poor surrounding road infrastructure. By the late nineteenth century, road development partisans began to coalesce into a national "Good Roads" movement. A weak federal Office of Road Inquiry was established in 1892, but had no real authority or budget. Federal promises in the 1890s to develop an elaborate Rural Free Delivery system failed to materialize. Dixie Highway details how Good Roads activism (fueled by a fragile coalition of farmers, businessmen, and the nascent automobile industry) accelerated nationwide after 1910 when affordable automobiles vastly expanded the potential for an upgraded road network to present a viable alternative for long-distance travel. Good Roads activists began to lobby for a federally-funded highway system, and, after 1914, planning for the Dixie Highway commenced.

The idea for the highway, Ingram notes, came from Indianapolis automotive headlights manufacturer Carl Fisher, who had plowed his fortune into the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, and later into promoting long-distance roads, including the earlier Lincoln Highway. The Dixie Highway—one of a number of "marked trails" of this era—would join existing local roads into a long-distance highway linking north and south. Not coincidentally, it would connect the metropolitan North with Fisher's new real estate venture in the mangrove swamps of south Florida—Miami Beach. Despite Fisher's self-interested agenda, the idea attracted broad support from farmers, businessmen and tourism promoters, automobile enthusiasts, and state officials. The Dixie Highway Association, founded in 1915 by Fisher and other businessmen, spearheaded their lobbying and planning efforts.

|

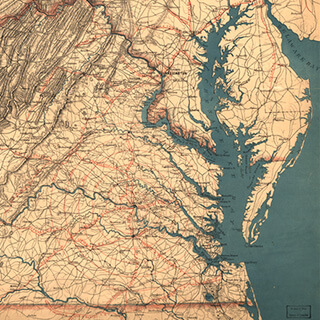

| Outline of the Dixie Highway, The Dixie Highway Association, 1915-1927. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. |

Bringing Dixie Highway to fruition at this moment when there was no political consensus about road building proved arduous. Ingram explains how disagreements erupted over routing, state and gubernatorial power to designate routes, and concerns about funding and labor sources. At a major meeting in Chattanooga in 1915 "[e]veryone wanted to be involved in planning the Dixie Highway," Ingram quips, "but no one knew how to do it" (76).

In Ingram's narrative, the thorniest questions concerned the need for federal money and more centralized state control. Having inaugurated the project by raising insufficient funds from counties, after 1915 the Dixie Highway Association joined the growing national chorus calling for federal highway aid. Such efforts spurred passage of the first Federal Aid Road Act in 1916 with, Ingram notes, the strong support of southern congressmen. The Act, limited in scope, mandated creation of highway departments in states that wanted to receive federal funds, but lacked other provisions that would have allowed it more fully to support efforts like the Dixie Highway.

Ingram presents World War I as a key turning point. The war bolstered the new state highway departments and calls for expanded federal involvement in road building by revealing the severe limitations of both the nation's railroad and highway infrastructure (which could not handle increasing truck traffic). Advocates of the Dixie Highway and similar routes began to cast their projects as national defense investments rather than just commercial or tourist amenities.

Meanwhile, the growth of domestic tourism during wartime spurred demand not only for road improvements, but also for standardized signage, maps, and travel guides. One wishes that Ingram had explored drivers' early experiences on the Dixie Highway in relation to the larger politics.

The country moved haltingly towards a national highway system. While the Dixie Highway Association advocated "expert engineering, paid labor, and modern machinery" (131) for road construction, many southern states remained committed to a chain gang labor system using (mostly) black convicts. Although the chain gang system was inefficient and ineffective in building quality roads, Ingram says that southern states clung to it as a pillar of (localized) racial control, as well as a way to avoid levying new fees or issuing road-building bonds.

Ingram writes that even after passage of an enhanced Federal Aid Highway Act in 1921, "[t]raditional racial politics collided with the modernizing impulses of the Good Roads Movement along the Dixie Highway" (132). Rifts opened in the movement, and progress on the highway lagged. But national sentiments were changing. In the 1920s, the roads movement culminated in the Bureau of Public Roads' designation of a national system of numbered federal highways. This system subsumed named routes like the Dixie Highway and, Ingram observes, "symbolized a significant transfer of power from local governments to a new centralized highway administration run by unelected state and federal bureaucrats" (174).

Meanwhile, in Georgia, the impulses to retain local control and resist bond- or license-driven statewide funding of highway construction reigned supreme. Ingram details how voters in the 1926 gubernatorial election elevated a pay-as-you-go advocate and highway department critic to the top of state government. "In many ways," Ingram concludes, the race "placed the massive success of the Dixie Highway campaign up for a popular vote, and it lost" (192).

In other southern states, too, "voters recoiled at the power and the cost of the state and federal institutions necessary to implement actual road construction" (193). This sentiment, Ingram argues—relying on data from South Carolina only—prevailed across the South until the 1950s, when the 1956 Federal Aid Highway Act mandated the interstate system based on the centralized, coordinated, national road building ideas that had underlain the Dixie Highway.

In using the Dixie Highway's history to map the contours of early twentieth century US highway politics, Ingram's book is successful. Yet, even on its own terms, the book feels partial and incomplete.

|

| Logo for the Georgia Dixie Highway Association and 90-mile Yard Sale. © Dixie Highway 90-Mile Yard Sale, 2015. |

The most significant shortcoming is that, while positioning itself as a history of the cross-country interstate "Dixie Highway," substantial parts of the book focus on internal politics in just one state: Georgia. Ingram defends this choice on the basis that Georgia had more Dixie Highway mileage than most other states, was heavily populated but poorly served by improved roads, was the "gateway to Florida" (10, 58), and provides a useful window into larger debates about centralization, planning, funding, and labor.

Dixie Highway's tendency to use Georgia as a proxy for "the South" seems unwarranted, as does the contention that attitudes in "the South" (towards highway expansion or anything else) were generally shared, uniquely shaped by racism, or differed fundamentally from those elsewhere. Discussions of problematic systems in Georgia (e.g. chain gang labor) find no parallel explorations or robust comparisons to labor or funding arrangements in other Dixie Highway states. What were the differences? Besides the chain gang, did other racial (or class) dynamics play out elsewhere along the Dixie Highway (e.g. in terms of route, travelers, accommodations, etc.)?

Regarding attitudes toward state-sponsored highway building, North Carolina's history presents a productive counter-narrative. In the early 1920s, that state issued bonds for an aggressive state-managed road construction program, bucking prevailing trends in Georgia, Virginia, and other southern states and earning the state the "Good Roads" moniker. Although North Carolina had only a small piece of the Dixie Highway, its distinctly different approach to road building finds little representation in Ingram's analysis of "the South."

Equally troubling is the absence from the narrative of Florida, a major Dixie Highway state and the road's southern destination. With the highway a key to south Florida's 1920s real estate and tourism boom (and with both state and private developers sponsoring other road projects like the Tamiami Trail and Tampa's Gandy Bridge), how did Florida state politics compare with Georgia's, where the social and economic context was very different? Ingram makes only cursory attempts at linkages between southern states but implies a broad consensus: "white southerners viewed the creation and expansion of a new highway bureaucracy with a mixture of enthusiasm and caution" (163).

|

| Dixie Highway in the Tampa Bay region. Photograph by the Burgert Brothers, 1925. Courtesy of Burgert Brothers Collection of Tampa Photographs and the University of South Florida Tampa Library, Florida Studies Center Gallery, Image 167. |

The book's conceptualization of key components of Dixie Highway history also betrays the expansive title. Ingram affords scant attention to those who traveled the highway, the expansion of tourism or commerce along the road, anything related to the road's effects on property owners, or the cultural and social dynamics of road development beyond their impact on construction-related state political debates. Dixie Highway's potential to use the road's history to explicate "the making of the modern South" is limited.

The work's potential is also limited by the constraints of the book as a mode of presentation. Could a topic such as highway history be better executed in a media rich, online format? Especially with regard to the Dixie Highway's fundamentally spatial stories of alternative routes, travel, urban-rural divides, state-based differences, and a massive physical transformation of a large swath of the US landscape, readers would benefit from interactive, dynamic maps (showing the halting progress of construction); layered geo-referenced overlays (that would relate the highway, now largely vanished, to the present landscape); infographics (comparing funding, labor, improved road mileage, and other factors across the states, and allowing visualization of regional differences); and plentiful video and images (postcards, advertisements) from the Dixie Highway's golden era.

There are now many models for web and video interpretation of spatial and highway histories; see, for instance, the 2013 film, Paving the Way: The National Park-to-Park Highway, which presents the history of a contemporaneous project to the Dixie Highway or my own Driving Through Time: The Digital Blue Ridge Parkway project. Tools like Neatline, DH Press, and others permit geospatial presentation of historical materials. Given the possibilities, Dixie Highway's selection of some twenty images (concentrated in the chapter on World War I) and limited set of maps (some of which—crucially the 1926 national highway system map on pages 190–191, and the official Dixie Highway map, which appears only on the dust jacket—are very difficult to see) seems unequal to the task.

One hopes, given these exciting possibilities, that Tammy Ingram's Dixie Highway could spur further examinations in multiple formats of this crucial transitional period in American transportation history.

About the Author

Anne Mitchell Whisnant is adjunct associate professor of history and American studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She also serves as deputy secretary of the faculty in the office of faculty governance. Her publications include Super-Scenic Motorway: A Blue Ridge Parkway History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006). Whisnant is the scholarly advisor for "Driving Through Time: The Digital Blue Ridge Parkway in North Carolina," a grant-funded digital, geospatial history collection developed collaboratively with the Carolina Digital Library and Archives, part of the UNC libraries system.

Recommended Resources

Text

Colombo, Jesse. "The 1920s Florida Real Estate Bubble." The Bubble Bubble, June 26, 2012. Accessed December 23, 2014. http://www.thebubblebubble.com/florida-property-bubble/.

Lowry, Amy Gillis and Abbie Tucker Parks. North Georgia's Dixie Highway. Mount Pleasant, SC: Aracadia Publishing, 2007.

Mormino, Gary R. Land of Sunshine, State of Dreams: A Social History of Modern Florida. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2008.

Whisnant, Anne Mitchell. Super-Scenic Motorway: A Blue Ridge Parkway History. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Whisnant, David E. and Anne Mitchell Whisnant. Small Park, Large Issues: DeSoto National Memorial and the Commemoration of a Difficult History. National Park Service Southeast Region, 2007.

Web

"Cruising the Dixie Highway." Chattanooga Public Library. http://chattlibrary.org/local-history/exhibits/start/cruising-dixie-highway.

"Driving Through Time: The Digital Blue Ridge Parkway." University of North Carolina Libraries. http://docsouth.unc.edu/blueridgeparkway/.

Video

"PAVING THE WAY: The National Park-to-Park Highway." Directed by Brandon Wade. Accessed December 23, 2014. http://pavingtheway.tv/video.html