Overview

Diana McClintock reviews Gordon Parks: Segregation Story, a photography exhibit of both well-known and recently uncovered images by Gordon Parks (1912–2006), an African American photojournalist, writer, filmmaker, and musician. The exhibit is on display at Atlanta's High Museum of Art through June 21, 2015. All photographs appear courtesy of The Gordon Parks Foundation.

Review

|

| Children at Play, Mobile, Alabama, 1956. Photograph 37.002 by Gordon Parks. Courtesy of and copyright by The Gordon Parks Foundation. |

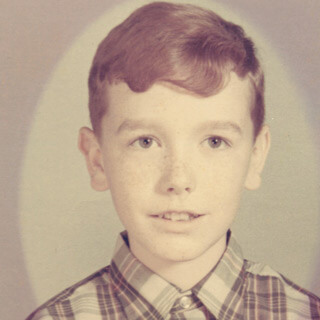

A grandfather holds his small grandson while his three granddaughters walk playfully ahead on a sunny, tree-lined neighborhood street. A middle-aged man in glasses helps a girl with puff sleeves and a brightly patterned dress up to a drinking fountain in front of a store. Five girls and a boy watch a Ferris wheel on a neighborhood playground. Shot in 1956 by Life magazine photographer Gordon Parks on assignment in rural Alabama, these images follow the daily activities of an extended African American family in their segregated, southern town. When they appeared as part of the Life photo essay "The Restraints: Open and Hidden" however, these seemingly prosaic images prompted threats and persecution from white townspeople as well as local officials, and cost one family member her job. The calm demeanor of Parks's subjects belies the injustice of the "separate but unequal"1Charlayne Hunter-Gault, "Doing the Best We Could with What We Had," in Gordon Parks: Segregation Story (Göttingen, Germany: Steidl, with the Gordon Parks Foundation and the High Museum of Art, 2014), 8–10. Hunter-Gault uses the term "separate but unequal" throughout her essay. conditions of their lives in the Jim Crow South: the girl drinks from a "colored only" fountain, and the six African American children look through a chain-link fence at a "white only" playground they cannot enjoy. "Out for a stroll" with his grandchildren, according to the caption in the magazine, the lush greenery lining the road down which "Old Mr. Thornton" walks "makes the neighborhood look less like the slum it actually is. Like all but one road in town, this is not paved; after a hard rain it is a quagmire underfoot, impassable by car."2Robert Wallace, "The Restraints: Open and Hidden," Life Magazine, September 24, 1956, reproduced in Gordon Parks, 106.

Parks took more than two-hundred photographs during the week he spent with the family. All but the twenty-six images selected for publication were believed to be lost until recently, when the Gordon Parks Foundation discovered color transparencies wrapped in paper with the handwritten title "Segregation Series." Gordon Parks: A Segregation Story, on view at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta through June 21, 2015, presents the published and unpublished photographs that Parks took during his week in Alabama with the Thorntons, their children, and grandchildren.

|  |  | ||

| Untitled, Shady Grove, Alabama, 1956. Photograph 37.005 by Gordon Parks. Courtesy of and copyright by The Gordon Parks Foundation. | Untitled, Alabama, 1956. Photograph 37.066 by Gordon Parks. Courtesy of and copyright by The Gordon Parks Foundation. | Ondria Tanner and her Grandmother Window-shopping, Mobile, Alabama, 1956. Photograph 37.007 by Gordon Parks. Courtesy of and copyright by The Gordon Parks Foundation. |

Parks's extensive selection of everyday scenes fills two large rooms in the High. Wall labels offer bits of historical context and descriptions of events with a simplicity that matches the understated power of the images. For example, one of several photos identified only as Untitled, Shady Grove, Alabama, 1956, shows two nicely dressed women, hair neatly tucked into white hats, casually chatting through an open window, while the woman inside discreetly nurses a baby in her arms. Centered in front of a wall of worn, white wooden siding and standing in dusty gray dirt, the women's well-kept appearance seems incongruous with their bleak surroundings. Children at Play, Alabama, 1956, shows boys marking a circle in the eroded dirt road in front of their shotgun houses. In Untitled, Alabama, 1956, displayed directly beneath Children at Play, two girls in pretty dresses stand ankle deep in a puddle that lines the side of their neighborhood dirt road for as far as the eye can see. In Ondria Tanner and her Grandmother Window Shopping, Mobile, Alabama, 1956, a wide-eyed girl gazes at colorfully dressed, white mannequins modeling expensive clothes while her grandmother gently pulls her close. The lack of overt commentary accompanying Parks's quiet presentation of his subjects, and the dignity with which they conduct themselves despite ever-present reminders of their "separate but unequal" status in everyday life, offers a compelling alternative to the more widely circulated photographs of brutality and violence typical of civil rights photography.

|

| Outside Looking In, Mobile, Alabama, 1956. Photograph 37.008 by Gordon Parks. Courtesy of and copyright by The Gordon Parks Foundation. |

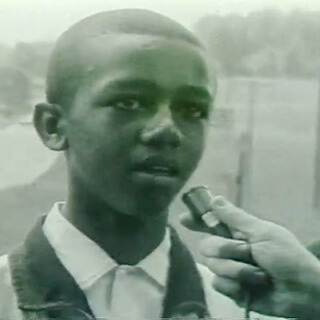

In the exhibition catalogue essay "With a Small Camera Tucked in My Pocket," Maurice Berger observes that this series represents "Parks'[s] consequential rethinking of the types of images that could sway public opinion on civil rights."3Maurice Berger, "With a Small Camera Tucked in My Pocket," in Gordon Parks, 12. His full-color portraits and everyday scenes were unlike the black and white photographs typically presented by the media, but Parks recognized their power as his "weapon of choice" in the fight against racial injustice.4Ibid. Furthermore, Parks's childhood experiences of racism and poverty deepened his personal empathy for all victims of prejudice and his belief in the power of empathy to combat racial injustice. His photograph of African American children watching a Ferris wheel at a "white only" park through a chain-link fence, captioned "Outside Looking In," comes closer to explicit commentary than most of the photographs selected for his photo essay, indicating his intention to elicit empathy over outrage.

However powerful Parks's empathetic portrayals seem today, Berger cites recent studies that question the extent to which empathy can counter racial prejudice—such as philosopher Stephen T. Asma's contention that human capacity for empathy does not easily extend beyond an individual's "kith and kin."5Ibid. Clearly, the persecution of the Thornton family by their white neighbors following their story's publication in Life represents limits of empathy in the fight against racism.

|

| Mr. and Mrs. Albert Thornton, Mobile, Alabama, 1956. Photograph 37.003 by Gordon Parks. Courtesy of and copyright by The Gordon Parks Foundation. |

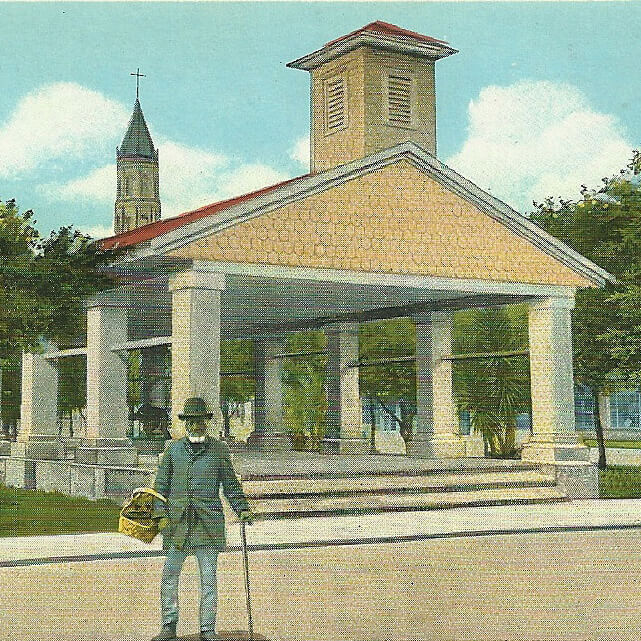

Parks's Life photo essay opened with a portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Albert Thornton, Sr., seated in their living room in Mobile. Above them in a single frame hang portraits of each from 1903, spliced together to commemorate the year they were married. Mrs. Thornton looks reserved and uncomfortable in front of Parks's lens, but Mr. Thornton's wry smile conveys his pride as the patriarch of a large and accomplished family that includes teachers and a college professor. Photos of their nine children and nineteen grandchildren cover the coffee table in front of them, reflecting family pride, and indexing photography's historical role in the construction of African American identity.

As a relatively new mechanical medium, training in early photography was not restricted by racially limited access to academic fine arts institutions. African Americans Jules Lion and James Presley Ball ran successful Daguerreotype studios as early as the 1840s. During and after the Harlem Renaissance, James Van der Zee photographed respectable families, basketball teams, fraternal organizations, and other notable African Americans. Thomas Allen Harris, director of the 2014 documentary Through a Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People, recalls the importance of photography to his own family:

Photography was a means of unifying our extended family . . . one generation with the next. . . . My grandfather's living room was a gallery; filled with the images of famous Black leaders as well as the images of our forbearers, interspersed with his own photos. . . . Like grandfather's stories describing his great grandparents making their way out of slavery and building their lives into something despite the pervasive and crippling racial barriers they faced, the legacy of these photographic images proudly showed us who we were.6Thomas Allen Harris, interviewed by Craig Phillips, "Thomas Allen Harris Goes Through a Lens Darkly," Independent Lens Blog, PBS, February 13, 2015, http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/blog/thomas-harris-goes-lens-darkly.

|

| Department Store, Mobile, Alabama, 1956. Photograph 37.011 by Gordon Parks. Courtesy of and copyright by The Gordon Parks Foundation. |

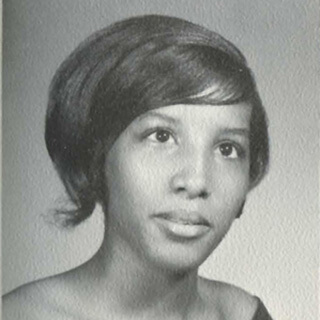

Parks mastered creative expression in several artistic mediums, but he clearly understood the potential of photography to counter stereotypes and instill a sense of pride and self-worth in subjugated populations. Berger recounts how Joanne Wilson, the attractive young woman standing with her niece outside the "colored entrance" to a movie theater in Department Store, Mobile Alabama, 1956, complained that Parks failed to tell her that the strap of her slip was showing when he recorded the moment: "I didn't want to be mistaken for a servant. Dressing well made me feel first class. I wanted to set an example."7Berger, 15. Parks's presentation of African Americans conducting their everyday activities with dignity, despite deplorable and demeaning conditions in the segregated South, communicates strength of character that commands admiration and respect. The headline in the New York Times photography blog Lens, for Berger's 2012 article announcing the discovery of Parks's Segregation Series, describes it as "A Radically Prosaic Approach to Civil Rights Images."8Maurice Berger, "A Radically Prosaic Approach to Civil Rights Images," Lens, New York Times, July 16, 2012, http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/07/16/a-different-approach-to-civil-rights-images/. It is precisely the unexpected poetic quality of Parks's seemingly prosaic approach that imparts a powerful resonance to these quiet, quotidian scenes.

About the Author

Diana McClintock is associate professor of art history at Kennesaw State University and was previously an associate professor of art history at the Atlanta College of Art. Prior to entering academia she was curator of education at Laguna Art Museum and a museum educator at the Municipal Art Gallery in Los Angeles. McClintock's current research interests include the examination of changes to art criticism and critical writing in the age of digital technology, and the continued investigation of "Outsider" art and new critical methodologies. McClintock also writes for ArtsATL, an open access contemporary art periodical.

Acknowledgments

Southern Spaces thanks The Gordon Parks Foundation and the High Museum of Art for their assistance with this review. All images courtesy of The Gordon Parks Foundation.

Recommended Resources

Text

Gordon Parks Foundation and the High Museum of Art. Gordon Parks: Segregation Story. Göttingen, Germany: Steidl, 2014.

Kennedy, Randy. "'A Long, Hungry Look': Forgotten Parks Photos Document Segregation." New York Times, December 24, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/28/arts/design/gordon-parks-photos-document-segregation.

Parks, Gordon. Voices in the Mirror. New York: Doubleday, 1990.

Parr, Ann, and Gordon Parks. Gordon Parks: No Excuses. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, 2006.

Stange, Maren. Bare Witness: Photographs by Gordon Parks. Milan, Italy: Skira, 2006.

Willis, Deborah, and Barbara Krauthamer. Envisioning Emancipation: Black Americans and the End of Slavery. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012.

Willis, Deborah. Family History Memory: Recording African American Life. New York: Hylas, 2005.

———. Reflections in Black: a History of Black Photographers, 1840 to the Present. New York: W. W. Norton, 2000.

Web

Berger, Maurice. "A Radically Prosaic Approach to Civil Rights Images." Lens, New York Times, July 16, 2012. http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com//2012/07/16/a-different-approach-to-civil-rights-images/.

The Gordon Parks Foundation. "Archive." http://www.gordonparksfoundation.org/archive.

Phillips, Craig. "Thomas Allen Harris Goes Through a Lens Darkly." Independent Lens Blog, PBS, February 13, 2015. http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/blog/thomas-harris-goes-lens-darkly.

Video

Harris, Thomas Allen. Through a Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People. Documentary, 2014.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Charlayne Hunter-Gault, "Doing the Best We Could with What We Had," in Gordon Parks: Segregation Story (Göttingen, Germany: Steidl, with the Gordon Parks Foundation and the High Museum of Art, 2014), 8–10. Hunter-Gault uses the term "separate but unequal" throughout her essay. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Robert Wallace, "The Restraints: Open and Hidden," Life Magazine, September 24, 1956, reproduced in Gordon Parks, 106. |

| 3. | Maurice Berger, "With a Small Camera Tucked in My Pocket," in Gordon Parks, 12. |

| 4. | Ibid. |

| 5. | Ibid. |

| 6. | Thomas Allen Harris, interviewed by Craig Phillips, "Thomas Allen Harris Goes Through a Lens Darkly," Independent Lens Blog, PBS, February 13, 2015, http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/blog/thomas-harris-goes-lens-darkly. |

| 7. | Berger, 15. |

| 8. | Maurice Berger, "A Radically Prosaic Approach to Civil Rights Images," Lens, New York Times, July 16, 2012, http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/07/16/a-different-approach-to-civil-rights-images/. |