Overview

Chenoa Flippen reviews Sarah Mayorga-Gallo's Behind the White Picket Fence: Power and Privilege in a Multiethnic Neighborhood (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

Review

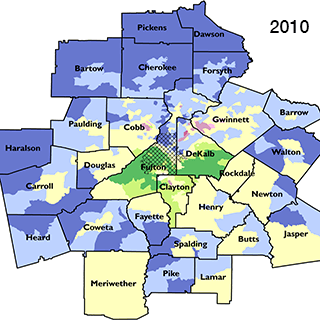

Sarah Mayorga-Gallo's Behind the White Picket Fence explores how race, class, and ethnicity shape daily life and power sharing in "Creekridge Park," a pseudonymous multiethnic neighborhood located in Durham, North Carolina. In the early twentieth century, the neighborhood was predominantly white working- and middle class, but as the housing stock aged in the late 1980s, more African American families gained access. Creekridge Park also experienced an influx of Latino immigrants after 2000, as the overall Latino population of Durham grew rapidly. With a mix of single-family homes and apartment complexes built during different periods, the neighborhood was home to 1,570 people in 2010, among whom 34 percent were non-Hispanic white, 39 percent were black, and 26 percent were Hispanic. At that time, 66 percent of residents were renters.

Given the demographics, one might suppose that Creekridge Park represents a well-integrated racial and ethnic neighborhood. However, drawing on interviews, surveys, and participant observation, Mayorga-Gallo, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Cincinnati, argues against the "tyranny of proportionality," or the over-reliance on statistical measures of neighborhood diversity and integration (6). Nominal integration does not equate with power and resource sharing, equal status, or reciprocity in relationships; rather, closer examination of the everyday interactions among residents reveals how seemingly benign and race-neutral practices perpetuate inequality.

A central theme of Behind the White Picket Fence is that middle-class whites utilize many resources to maintain power while simultaneously extolling the virtues of their multiethnic environment. Deploying what Mayorga-Gallo terms a "diversity ideology," whites extol the neighborhood's funky charm and eclectic mix of housing and population (race, ethnicity, class, sexual orientation, and family type), and yet maintain mostly homogeneous friendships and make little effort to include or address the needs of minority residents (23, 55–57). Mayorga-Gallo likens diversity ideology to colorblind racism,1Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, Racism without Racists: Color Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2013). a concept predicated on the notion that intentions, not outcomes, are what matter: valuing diversity is considered enough, even if behaviors, structures, and institutions reproduce inequality. This ideology allows white residents to celebrate progressiveness while failing to promote meaningful inclusion.

Creekridge Park Demographics. Map by George Mayorga. From Behind the White Picket Fence: Power and Privilege in a Multiethnic Neighborhood by Sarah Mayorga-Gallo. Copyright © 2014 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher. www.uncpress.unc.edu.

According to Mayorga-Gallo, Creekridge Park's local neighborhood association illustrates this dynamic. Its membership, comprised almost exclusively of white homeowners, is far from demographically representative of the neighborhood. Rather than understanding the lack of minority representation as undermining their legitimacy, association members rationalize it as the tendency for minority residents to be renters and less invested in the neighborhood. By emphasizing the universality and neutrality of the organization, and insisting that they work to better the neighborhood for all residents, board members excuse themselves from considering the fundamental importance of inclusion. Mayorga-Gallo illustrates how the association's promotional practices are a key source of minority underrepresentation. The quarterly neighborhood newsletter is distributed door-to-door for single-family homes, but not to apartments; events are announced via an email listserv and are seldom advertised in Spanish. Such practices tend to exclude renters and residents of color. Aware of these limitations, and occasionally voicing the need for correction, board members take no action; instead, they create an all-white space that discourages broader participation.

Mayorga-Gallo also argues that white homeowners, many of whom are recent additions to the neighborhood, not only assume they are entitled to mandate local norms but, because of race and class power, actively do so. The resulting "white codes" dictate appropriate behavior, producing mostly mono-racial social networks and maintaining a high degree of social distance despite physical proximity (59, 92–93). Accordingly, white owners opposed higher density additions and pursued more stringent construction standards as part of a greening initiative; meddled in how their neighbors treated their dogs; entered others' yards to pick up trash; set the terms for participating in the community garden; and were often patronizing to lower-class neighbors. They pursued neighborhood watch programs, cultivated a close relationship with the police, and were quick to resort to formal methods of addressing complaints (particularly by calling the police), rather than privileging face-to-face interactions with neighbors.

These seemingly non-racial practices produce highly racialized outcomes. For African Americans, living in Creekridge Park brings material benefits at the cost of social isolation and everyday insensitivities. Gentrifying upgrades to commercial spaces alienate low-income blacks. Mayorga-Gallo's findings suggest that Latino residents are often more quiescent, attributing their lack of interaction with neighbors to language barriers, rather than to social exclusion. However, their second-class status is reinforced when they participate in neighborhood events.

Behind the White Picket Fence ends with a call to action. Mayorga-Gallo argues that statistical integration should not be an ultimate goal for researchers or policy makers. The relationship between proximity and equity is not fixed. Instead, diversity can reinforce white privilege just as easily as it can promote equity and justice. She urges us to reframe the conversation about racial inequality from one about good and bad individuals to one about power, privilege, and outcomes. It is not enough to say that everyone is welcome at neighborhood meetings; Mayorga-Gallo calls for active minority recruitment and inclusion, balancing the interests of homeowners against those of renters.

Mayorga-Gallo's multifaceted insights contribute importantly to the topics of colorblind racism and urban ethnography—which rarely examines non-poor neighborhoods or those outside of central cities. Understanding white middle-class practices of exclusion is essential to understanding residential segregation and urban poverty. Moreover, Behind the White Picket Fence features a diversity of voices. Mayorga-Gallo interviewed long-time residents and newcomers, moved beyond the black-white binary to include Latinos, and spoke with owners and renters.

Future work could build on Mayorga-Gallo's analysis to link her findings with larger institutional contexts. Even if proximity does not foster diverse friendships or inclusion in neighborhood associations, it can promote meaningful social change if it boosts the tax base and contributes to school desegregation. Durham often loses middle-class residents to Chapel Hill or to other parts of the metro region with lower percentages of racial and class-based diversity. Desegregating residential neighborhoods is central to the goal of educational integration, which has suffered setbacks in recent years. There is intense and growing interest in how families weigh the characteristics of homes, neighborhoods, and schools when deciding where to live.2Annette Lareau and Kimberly Goyette, eds., Choosing Homes, Choosing Schools (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2014). Mayorga-Gallo observes that few Creekridge whites send their children to the local elementary school, which is predominantly minority, opting instead for charter or private schools. A sustained critique of the ways diversity ideology plays out would be a valuable extension of Behind the White Picket Fence, delving into the processes by which white parents rationalize valuing diversity on the block but not, for example, in the classroom.

About the Author

Chenoa Flippen is associate professor of sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. She completed her Ph.D. in sociology at the University of Chicago. Her research addresses the connection between racial and ethnic inequality and contextual forces at the neighborhood, metropolitan, and national levels.

Recommended Resources

Text

Brown, Leslie. Upbuilding Black Durham: Gender, Class, and Black Community Development in the Jim Crow South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Gill, Hannah. The Latino Migration Experience in North Carolina: New Roots in the Old North State. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Hirsch, Arnold R. Making the Second Ghetto: Race and Housing in Chicago 1940–1960. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Web

Phil Bost. Durham Hoods Interactive Map. http://durhamhoods.com/.

John Chesser. University of North Carolina Charlotte Urban Institute. Division of Academic Affairs. Hispanics in North Carolina. http://ui.uncc.edu/story/hispanic-latino-population-north-carolina-cities-census.

The City of Durham Demographics. Demographics. https://durhamnc.gov/386/Demographics.

Durham County Library. Durham Civil Rights Heritage Project. http://durhamcountylibrary.org/exhibits/dcrhp/.

United States Census. Durham Quick Facts. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/37/37063.html.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, Racism without Racists: Color Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2013). |

|---|---|

| 2. | Annette Lareau and Kimberly Goyette, eds., Choosing Homes, Choosing Schools (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2014). |