Overview

In this essay, Andrew M. Busch discusses the histories of segregation and gentrification in Austin, Texas's Eastside and examines the rise of New Urbanism in the development of the Eastside's Eleventh Street corridor. Busch ends with a call for spatial justice in which Austin's community development would be more inclusive.

Greetings from Austin

In July of 2011 Bon Appétit named Franklin Barbecue of Austin, Texas, the best barbecue restaurant in America. As one of the flagship businesses in an area of the city undergoing significant redevelopment Franklin (which began as a food truck three years earlier) had recently moved into a building on East Eleventh Street, adjacent to downtown across Interstate 35. Franklin Barbecue helped enhance the city's wider reputation while locally it helped the reputation of the central Eastside. The white-owned Franklin took the former space of Ben's Long Branch Barbecue, an African American–owned business operating since the 1980s; African Americans had served barbecue at this site since at least the early 1960s. The corridor, formerly the hub of black commerce and social life during the era of segregation, fell into blight and disrepair in the 1970s and sunk into deeper trouble by the 1980s as residents of means and local businesses fled. In the 1990s the Austin Revitalization Authority (ARA) was formed as a non-profit to assist in the commercial development of the neglected neighborhood as well as to renew historic buildings and homes to maintain architecture consistent with the area's heritage. In 1997 the ARA declared the area a slum, making it eligible for Section 108 Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).1Much of the early history of the ARA was marred by questionable real estate practices and stacking of the ARA board by councilman Eric Mitchell and his group of connected developers and politicians. Mitchell did not include any neighborhood representatives on the first ARA board. See A. D., "ARA Board Member Helps Himself," Austin Chronicle, January 12, 1996, http://www.austinchronicle.com/news/1996-01-12/530368/; Mike Clark-Madison, "The ARA Myth: Empty Promises on the Eastside," Austin Chronicle, June 20, 1997, http://www.austinchronicle.com/news/1997-06-20/529133/. After completing the Central East Austin Master Plan, which called for 140,000 square feet of mixed-use development, the ARA and the city acquired over $9 million in CDBGs to initiate revitalization. Almost all development took place along the Eleventh Street corridor.2Crone Urban Design Team, "New Visions of East Austin: Central East Austin Master Plan," Report, 1999, courtesy AHC.

Although development in the East Eleventh Street corridor began slowly, by the mid-2000s the area's importance to the city's Eastside efforts and to the downtown was apparent. Eleventh Street is one of only two downtown streets that bridge I-35, the physical barrier between minority and Anglo neighborhoods since its completion in 1962. People coming from downtown to East Eleventh do not have to pass underneath the highway. Signs displaying the East End slogan "Local Spoken Here" invite consumption along the corridor. A gateway arch laden with the Texas Star welcomes traffic from downtown. The cityscape here appears more modern, newer, and cleaner than much on the Eastside. Multiple use zoning allows for architecture consistent with New Urbanism: higher density, mixed use, better public transport and bike lanes, historic districts, and heritage-based public spaces. The area has undergone significant demographic change as middle class whites and upscale businesses have moved in.3Ryan Robinson, "Top Ten Demographic Trends in Austin, Texas," http://www.austintexas.gov/page/top-ten-demographic-trends-austin-texas, accessed December 18, 2014. Robinson is the city's demographer.

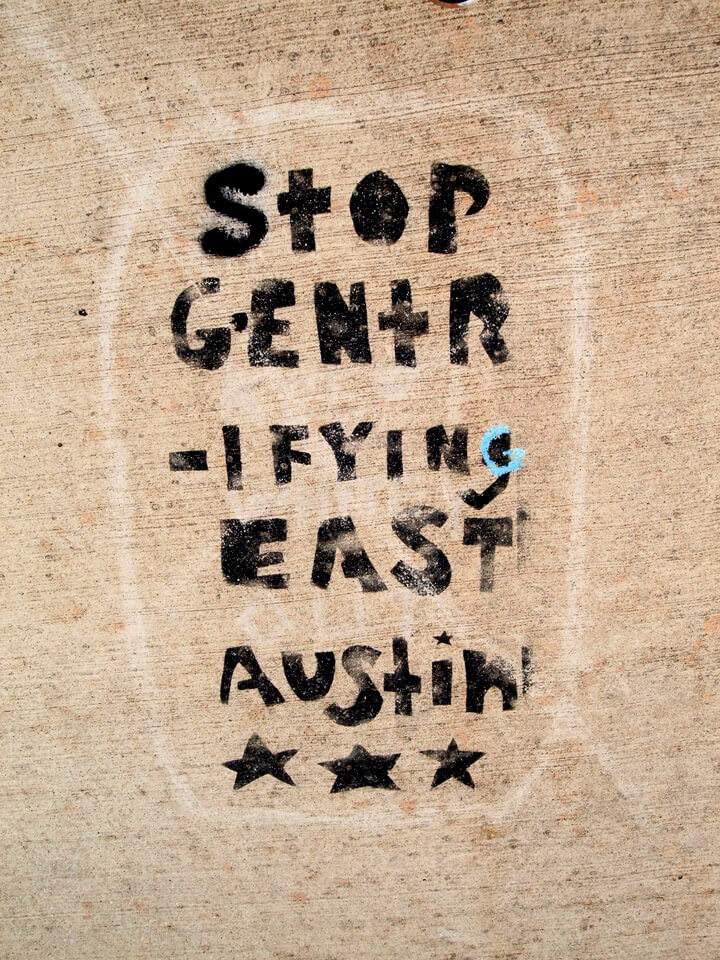

New Urbanism became the architecture of gentrification and redevelopment in Austin.4For theories of New Urbanism, see Peter Katz, The New Urbanism: Towards an Architecture of Community (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994); Congress for the New Urbanism, Charter of the New Urbanism (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000); Andres Duany, Jeff Speck, with Mike Lydon, The Smart Growth Manual (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010); Andres Duany, Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream (New York: North Point Press, 2001). Since the late 1990s, two trends are evident. First, there is new interest in urban space, lifestyles, and consumption preferences in a city long defined by suburbanism. Second, municipal leaders and real estate developers recognized the potential for significant increases in exchange values—and property taxes—by refurbishing parts of the neglected urban core. Since the 1980s, many US cities have become more entrepreneurial in attracting investment and stimulating development in areas deemed undervalued.5David Harvey, "From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation of Urban Governance in Late Capitalism," Geografiska Annaler 71. no. 1, Series B (1989): 3–17; Jason Hackworth, The Neoliberal City (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007); Gerald Dumenvil and Dominique Levy, Capital Resurgent: Roots of Neoliberal Revolution, trans. Derek Jeffers (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004). In Austin, gentrification and rising rents have forced displacement in neighborhoods that for decades housed the city's highest concentrations of African American and Latino residents.

The most deleterious outcome of gentrification is its effect on existing social cohesion, which is much more important for vulnerable and historically segregated neighborhoods of color where residents have fewer relocation options and are more dependent on the neighborhood for social structure than are residents of middle class neighborhoods.6John Betancur, "Gentrification and Community Fabric in Chicago," Urban Studies 48, no. 2 (2011): 383–406; Mark Davidson, "Spoiled Mixture: Where does State-led 'Positive' Gentrification End?," Urban Studies 45, no. 12 (2008): 2385–2405; Neil Smith, The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City (London: Routledge, 1996). Poorer minorities are more vulnerable to rent hikes and increased costs and are more dependent on place for community than wealthier groups. They also tend to understand community in terms of place, especially in historically segregated locations.7John R. Logan and Harvey Molotch, "Homes: Exchange and Sentiment in the Neighborhood," in Urban Fortunes: The Political Economy of Place (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987): 99–146; David Harvey, "Flexible Accumulation through Urbanization: Reflections on 'Post-Modernism' in the American City," in Post-Fordism: A Reader (Oxford: Blackwell, 1995): 361–386; Cynthia Horan, "Community Development, Racial Empowerment, and Politics," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 594 (2004): 158–170. Although gentrification is in some sense a function of market changes, political and economic disparities in the allocation of municipal capital undergird the relationship between gentrification and spatial justice in Austin. While the city uses public money to attract investment, subsidize more expensive development in East Austin, and generate tax revenue, it does not adequately invest to provide subsidies for affordable housing for long-term and disadvantaged neighborhood residents, many of whom have been forced out of Central East Austin or have lost friends and family to displacement.

The Austin example augments existing research on gentrification which seeks either to explain and critique the process or tell stories of change from residents' perspectives.8Important recent on gentrification process include Jason Hackworth and Neil Smith, "The Changing State of Gentrification," Journal of Economic and Social Geography 92, no. 4 (2001): 464–477; Rowland Atkinson and Gary Bridge, eds., Gentrification in a Global Context: The New Urban Colonialism (New York: Routledge, 2005); Loretta Lees, "Gentrification and Social Mixing: Towards an Inclusive Urban Renaissance?" Urban Studies 45, no. 12 (2008): 2449–2470. Studies emphasizing residents' perceptions include Japonica Brown-Saracino, A Neighborhood that Never Changes: Gentrification, Social Preservation, and the Search for Authenticity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009); Lance Freeman, There goes the 'Hood: Views of Gentrification from the Ground Up (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006). The literature on gentrification in Austin links the city's emphasis on environmental sustainability as a competitive advantage to externalities that displace vulnerable groups and generate or exacerbate socioeconomic inequality.9Eliot M. Tretter, "Contesting Sustainability: 'SMART Growth' and the Redevelopment of Austin's Eastside," International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37, no. 1 (January 2013): 297–310; Joshua Long, "Constructing the Narrative of the Sustainability Fix: Sustainability, Social Justice, and Representation in Austin, Texas," Urban Studies (December 2014): 1–24; Eugene J. McCann, "Inequality and Politics in the Creative City-Region: Questions of Livability and State Strategy," International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 31, no. 1 (March 2007): 188–196; Elizabeth J. Mueller and Sarah Dooling, "Sustainability and Vulnerability: Integrating Equity into Plans for Central City Redevelopment," Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 4, no. 3 (2011): 201–222; Emily Skop, "Austin: A City Divided," in The African Diaspora in the United States and Canada at the Dawn of the 21st Century, ed. John Frasier, Joe T. Darden, and Norah F. Henry (New York: Academic Publishing, 2009); Eric Tang and Chunhui Ren, Outlier: The Case of Austin's Declining African American Population (Austin: University of Texas Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis, 2014). Austin's experience also calls into question several recent studies which argue that gentrification has fewer negative outcomes on poor or minority neighborhoods than previously assumed.10Ingrid G. Ellen and Katherine M. O'Regan, "Gentrification and Low Income Neighborhoods: Entry, Exit, and Enhancement," Regional Science and Urban Economics 41, no. 2 (March 2011): 89–97; Jacob P. Vigdor, "Is Urban Decay Bad? Is Urban Revitalization Bad Too?" Journal of Urban Economics 68, no. 3 (2010): 277–289; J. Peter Byrne, "Two Cheers for Gentrification," Howard Law Journal 46, no. 3 (2003): 405–432. In this article, my approach draws from traditional perspectives: the production side, which understands gentrification as part of the larger forces of capital that transform and restructure urban physical landscapes11Foundational works on production side gentrification include Neil Smith, "Towards a Theory of Gentrification: A Back to the City Movement by Capital, not People," Journal of the American Planning Association 45, no. 4 (October 1979): 538–548; "Gentrification and Uneven Development," Economic Geography 58, no. 2 (April, 1982): 139–155; and The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City (New York: Routledge, 1996).; and the consumption side, that views consumer preference as the driving force.12David Ley, "Alternative Explanations for Inner-City Gentrification: A Canadian Assessment," Annals of the Association of American Geographers 76, no. 4 (December, 1986): 521–535; and The New Middle Class and the Remaking of the Central City (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996). Middle class consumers, developers, and planners view New Urbanism as environmentally-friendly architecture that reflects sustainable urban lifestyles. Longtime residents, most of whom are minorities and many of whom are economically disadvantaged, regard New Urbanism as producing new urban spaces that undermine the sustainability of their neighborhoods. While the former group focuses on how the built landscape enhances sustainability by lessening pollution and energy use and moving development away from pristine natural areas, the latter group seeks to explain gentrification’s deleterious socioeconomic effects on vulnerable populations.

Studying locally or regionally specific aspects of gentrification uncovers correlations between spatial reorganization, urban political economy, and historical experience. Two circumstances particular to Austin are important. Compared to most US cities, Austin historically had a much less fluid racial geography: de facto segregation was more intense and less driven by exchange values in the era before gentrification began. Furthermore, gentrification in Austin was initiated in the 1990s by the municipal government as a response to increased regulation of development on the city's western periphery, formerly a main area of growth, at the behest of the city's environmental movement. In 2000, Central East Austin had a poverty rate over 45 percent and over 95 percent of residents were black or Latino.13Elizabeth Sobel, "Austin, Texas: The East Austin Neighborhood" (Report of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2007).

New Urbanism plays a symbolic role in neighborhood change with some of its proponents viewing gentrification uncritically or positively. Long-term residents of the central Eastside often linked New Urbanism's architecture and zoning changes with potential gentrification, requiring neighborhood groups to act defensively rather than as agents of positive social change. Once gentrification began, the already meager neighborhood resources available increasingly went to defend against demographic change and upscale development. New Urbanism can mean one thing for Austin residents who are likely to be displaced as property values and taxes rise, but something else for Austin's middle class residents and consumers.14Andres Duany, one of the principle architects of New Urbanism and perhaps its most famous proponent, celebrates gentrification. See Duany, "Three Cheers for Gentrification!: It Helps Revive Cities and Doesn't Hurt the Poor," American Enterprise (April 2001): 38–39; Martin Boddy, "Designer Neighborhoods: New Built Residential Development in Non-Metropolitan UK Cities—the Case of Bristol," Environment and Planning A 39, no. 1 (January 2007): 86–105.

Beginning with a discussion of the East Eleventh Street corridor as it exists today, this essay moves into a brief history of racial geography in Austin before addressing the political and economic factors that drove investment. Engaging with architectural theory, a subsequent section examines how New Urbanism and historical preservation altered the cityscape. Following Tom Slater's call to study working class displacement and resistance to gentrification, the essay concludes by asking how Austin residents and neighborhood groups approached gentrification, its symbols and causes, and its relationship to political and economic drivers of urban transformation.15Tom Slater, "A Literal Necessity to be Replaced: A Rejoinder to the Gentrification Debates," International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 32, no. 1 (March 2008): 212–223; and "The Eviction of Critical Perspectives from Gentrification Research," International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 30, no. 4 (December 2006): 737–757.

New Urbanism and the Symbolic Economy on East Eleventh Street

Pragmatically, producing urban space depends on the deployment of capital and labor. But city building also requires symbols and signs indicating who is accepted in a place and who is not, what should be visible and what should not. Developers used New Urbanism on Eleventh Street and along the Eastside to signal middle class consumption space. Producing a sense of local history and diversity was also important to the Austin Revitalization Authority's effort. The city lowered taxes for the redevelopment of historical structures. The earliest projects redeveloped buildings such as two structures dating from the late nineteenth century, the Haenhel Building and the Arnold Bakery, which were refurbished and rented to businesses. The next projects were larger live-and-work facilities featuring retail on the ground floor with living spaces above and taking advantage of zoning variances intended to increase density and public activity along the corridor. The tallest buildings were only four stories.16Brant Bingamon, "Old Homes=New Yuppies," Austin Chronicle, July 19, 2002. For symbolic economy, see Sharon Zukin, The Culture of Cities (New York: Blackwell, 1995).

While the ARA used New Urbanism to reinvigorate an urban corridor, the outcome was a new space for private investment catering to middle class, mostly white, tastes. Designating buildings for preservation zoning within New Urban developments hastened neighborhood change. A number of scholars have criticized New Urbanism's complicity with capital in creating exclusionary spaces and "geographies of otherness," which reinforce or replicate spatial divisions.17K. Till, "Neotraditional Towns and Urban Villages: The Cultural Production of a Geography of 'Otherness.'" Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 11, no. 6 (1993): 709–732; Peter Marcuse, "The New Urbanism: The Dangers so Far," disP: The Planning Review 36, no. 140 (2000): 4–6; Eugene McCann, "Neotraditional Developments: The Anatomy of a New Urban Form," Urban Geography 16, no. 3 (1995): 210–233; Robyn Dowling, "Neotraditionalism in the Suburban Landscape: Cultural Geographies of Exclusion in Vancouver, Canada," Urban Geography 19. no. 2 (1998): 105–122. In general, these studies examine New Urban developments on open space or in suburban locations rather than in urban cores undergoing transformation. Although they generally point to the exclusionary architecture and high prices associated with New Urbanism, they do not link it to gentrification. Austin's urban corridor development demonstrates this connection.

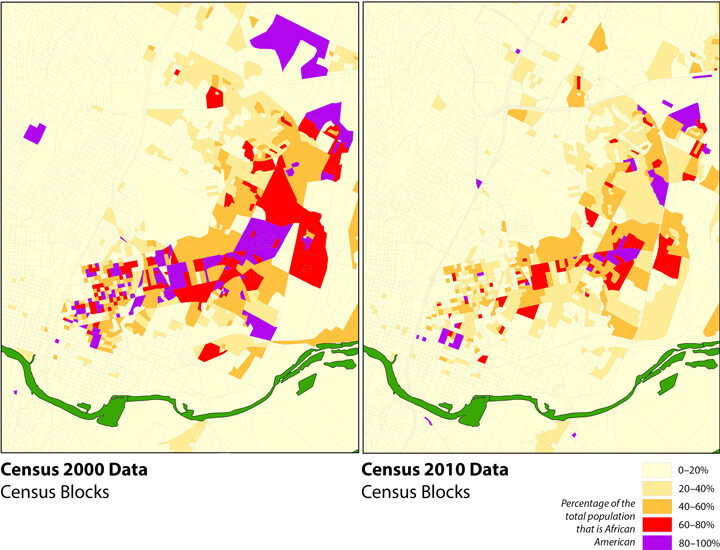

According to the ARA, Eleventh Street's understated design "reflects the way the street was originally developed," incorporating local history into the corridor.18Crane Urban Design Team and Austin Revitalization Authority, "New Visions of East Austin: Central East Austin Master Plan," (Austin: Austin Revitalization Authority, 1999). Public space is incorporated over a three-block span. Wider sidewalks encourage pedestrians. Federal funds went to build bus stops and bike lanes and widen streets to promote public transportation. The most symbolic public spot in the corridor is Urdy Plaza, an open, art-decorated space that honors the African American heritage of the district and longtime Austin African American leader, Charles Urdy. Local African American artist John Yancy and his team created a tile mural called "Rhapsody" depicting African American jazz musicians (a nod to the cultural history of the street as part of the chitterling circuit), as well as a scene that appears to be taken from the neighborhood's interracial origins in the late nineteenth century. The historical Ebenezer Baptist Church, organized in 1875 and built in 1885 on the Eastside, takes its place in the background. While the mural is emblematic of a proud African American history in central East Austin, it also evokes a present in which African Americans have a much smaller presence here. In census district one, which includes Central East Austin as well as a large portion of historically African American East Austin, the number of African American residents declined by 3,711 (14.5 percent) from 2000 to 2010.19City of Austin, "District 1 Demographic Profile," http://www.austintexas.gov/sites/ default/files/files/Planning/Demographics/District_1_demographic_profile_2000_2010.pdf, accessed March 18, 2015. Core areas closer to downtown experienced more intense African American population loss.20City of Austin, "Changing African American Landscape—Eastern Core," http://www.austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/files/Planning/Demographics/ afam_change00_10_eastern_core.pdf, accessed March 18, 2015. The area is marketed as historically relevant in accord with Austin's new urban tastes, yet the new neighborhood reflects starkly different demographics and consumer preferences. The past is not problematized by the public art; heritage representations aim to fix identity and promote a sense of pride rather than acknowledge the problems of memorializing social domination. As older residents and businesses leave, the segregationist past seems less relevant while the happy representations of jazz and interracial community remain.

As with other urban spaces made safe for revitalization, condominiums and upscale shops in the Eleventh Street corridor use the language of new urbanity. Because Austin lacks the industrial infrastructure common to many gentrified neighborhoods in older cities, there is little nostalgia about urbanity here and few structures representing a vibrant past. Rather, the emphasis falls upon the consumption preferences of new dwellers. The recently-built East Village Lofts suggests a neighborhood in New York City. Equally important is the imagined "village in a city," where the idealized community of a small village is incorporated with the amenities and excitement of urbanity. The ARA centered this concept in its master plan for Central East Austin in 1999, imagining the corridor as an "urban village," "a place for higher intensity mixed-use development that can build on the present and historical strengths of the corridor" to revitalize the area.21Crane Urban Design Team and Austin Revitalization Authority, "New Visions of East Austin: Central East Austin Master Plan." This village-in-a-city identity is also found in the slogan used on a now-defunct aggregate living development called Paloma Austin: "The Pinnacle of 'boutique urban living.'"

Urban boutique suggests a neighborhood of exclusive shops and trendy condos, the antithesis of suburban tract housing and big box stores, but requiring a clearing of undesirables. Making urbanity trendy has meant the removal of what was once considered urban: working class minority populations and the shops and stores which served them, homeless people, and ugly structures, all lumped together as blight. Urban boutique replaces existing stores and services that cater to poorer consumers—which encourages them to move.22For a recent analysis of "boutiquing" in New York see Sharon Zukin et al., "New Retail Capital and Neighborhood Change: Boutiques and Gentrification in New York City," City and Community 8, no. 1 (March 2008): 47–64. In a city where historical urbanity connoted segregation and poverty, there was little about the neighborhood deemed worthy of retaining.

The ARA has also adopted a language reflecting the commercial character of the corridor as well as new urban consumption preferences featuring local chains of production, images of community, and environmental sustainability. In conjunction with the Austin Independent Business Alliance, the ARA adopted the slogan "Local Spoken Here" as its theme for its East Eleventh Street small businesses. The slogan attempts to attract urban consumers interested in the sustainability associated with locality and local economic vitality. But it also changes what is "local," bringing in businesses catering to newer residents. Wine shops, trendy restaurants, designer stores, and the like mark the neighborhood for upscale consumption. The ARA also began promoting a new moniker for the area. Instead of "Eastside," the product of eighty years of segregation, the ARA calls the corridor the "East End," signifying a continuum between downtown and a more general coming together of the central city. The East End also has historical significance as the name of the multiethnic neighborhood in the early twentieth century before institutional segregation took hold.

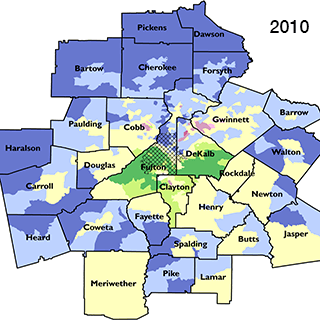

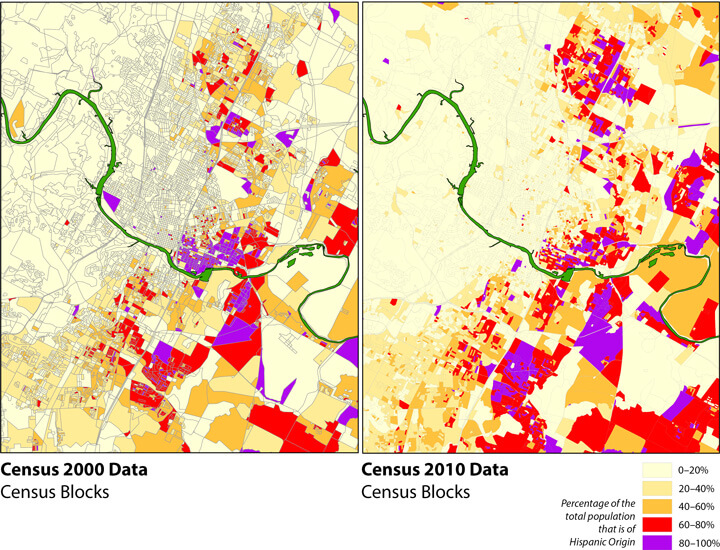

The symbolic reclamation of the East End as a viable part of the city's fabric signaled demographic changes that affected a much larger portion of the central Eastside. The goal of the ARA's public-private development was to increase investment. The Eleventh Street corridor opened up the area to grassroots gentrification, new single-family homes, condominiums, apartment complexes, and other commercial developments on the central Eastside. Between 2000 and 2010 formerly African American neighborhoods experienced intense demographic and economic changes. All four census tracts north of Seventh Street and south of Manor Road adjacent to I-35 experienced between 18 and 31 percent increases in white population between 2000 and 2010.23"Change in the White Percentage of Total Population, 2000 to 2010," (map), http://www.austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/files/Planning/Demographics/ travis_t2000_change_whit_core.pdf, accessed August 11, 2015. The same area experienced heavy African American outmigration, averaging 15.6 percent loss across the four tracts.24City of Austin, "Tract Level Change, 2000 to 2010, Total Population, Race and Ethnicity," spread sheet, http://www.austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/files/Planning/Demographics/ Tract_level_2000_to_2010_change.xlsx, accessed August 11, 2015. Along with increased development, the Anglo inmigration has had dramatic effects on property taxes. In the five years between 2000 and 2005, property taxes in the 78702 zip code, which covers the entire central Eastside from I-35 to Airport Boulevard and the Colorado River to Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, increased by over one hundred percent.25"Single Family Taxable Value: Percent Change, 2000 to 2005," (map), http://www.ci.austin.tx.us/demographics/downloads/sf_tax_perc.pdf, accessed September 27, 2011. The overall population on the central Eastside has also grown significantly younger, and the size of households has decreased dramatically as younger people without children have replaced families.26Ryan Robinson, "The Top Ten Big Demographic Trends in Austin, Texas," City of Austin, Planning and Zoning Department, http://www.austintexas.gov/demographics/, accessed August 11, 2015.

Race, History, and Geography in Austin

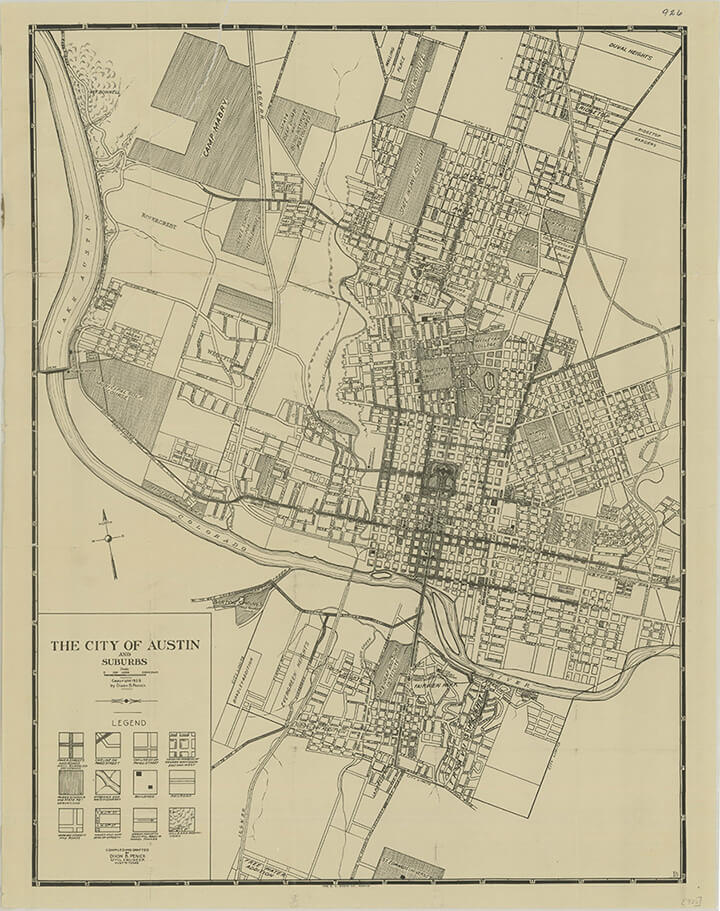

Austin's 1928 city plan imagined an urban space integrated with pastoral landscapes, the pristine University of Texas campus, and the state capitol grounds. Planners strongly discouraged industry, preferring to highlight features characteristic of a city whose primary activities were government and education: pleasant climate, natural beauty, cultural opportunities, and a relatively educated population. The primary function of the 1928 plan was to spatially segregate as much of the urban-industrial city as possible.27Koch and Fowler Consulting Engineers, "A City Plan for Austin, Texas," report, 1928. Courtesy of Austin History Center (AHC).

More significantly, and like other southern urban planning initiatives of the Jim Crow era, the plan also segregated racial minorities.28The chamber of commerce recommended engineers Koch and Fowler because of their success in instituting de facto segregation in the Dallas plan. See "John E. Surratt to Mr. W. E. Long," November 5, 1926/Long (Walter E.) Papers/Box 19/Folder, "City Plan Sept. 1926-Oct. 1927"/AHC; Kessler Plan Associates, "Needed City Planning Legislation," n.d./Long (Walter E.) Papers/ Folder, "City Plan Sept. 1926–Oct. 1927"/AHC; E. A. Wood, Dallas Morning News, August 8, 1926. As de jure segregation was illegal in Texas, planners used zoning and "separate but equal" legislation. They also simply removed African American services—schools, parks, and libraries—from neighborhoods designated as "white." The master plan bluntly stated that "there has been considerable talk in Austin, as well as other cities, in regard to the race segregation problem. This problem cannot be solved under any zoning law known to us at present. Practically all attempts at such have proved unconstitutional."29Koch and Fowler, "A City Plan," 58. At the time, according to plan, African Americans lived in small pockets throughout all the city's neighborhoods, with concentrations in Wheatville and Clarksville,30Clarksville, the first colony of free African Americans in Texas, remained unincorporated by the City of Austin and almost entirely African American well into the 1970s as the city literally grew around it. Much of the neighborhood remained without municipal services well into the 1970s as well, and streets were not paved. Since then, Clarksville has gentrified and is now one of Austin's most expensive neighborhoods. just northwest of downtown, and in the area east of East Avenue adjacent to downtown. To sidestep the constitutional issues posed by de jure segregation, consulting engineers Koch and Fowler recommended that the city relocate segregated facilities to one district and cut off facilities to minorities in all other parts of the city. By locating African American schools, parks, and municipal necessities in just one area, the "segregation problem" would take care of itself. They referred to this method of forced relocation as "an incentive to draw the negro population to this area."31Quoted in Koch and Fowler, "A City Plan," 57. While de facto segregation was already well underway and racially restrictive covenants were common in Austin's middle class subdivisions, the plan institutionalized racial segregation. The area became known as the Eastside.

The policy implementations were swift and effective. City records demonstrate that almost all African Americans were relocated to the Eastside by 1940. The African American school in Wheatsville, operating for sixty years, closed in 1932, and black population dropped from 16 percent of the census tract in 1930 to less than 1 percent by 1950. Residents who remained in Clarksville, the oldest free African American community in Texas, had no access to municipal facilities and the city made no improvements there until well into the 1970s. Although the plan did not mandate Latino segregation, similar forces coalesced to push the majority of Austin's Mexican American population into the neighborhood just south of the African American one. In 1939, the city of Austin built some of the first public housing units in the United States: the Santa Rita Courts designated for Latinos. Chalmers Court for whites and Rosewood Courts for blacks were similarly built in largely segregated neighborhoods.32Austin completed the first federally-funded public housing projects in the United States in 1938—one each for whites, Mexican Americans, and African Americans. Latinos did, however, remain more dispersed throughout areas in South Austin and on the outskirts of the city, but very few lived in white West Austin. Racially restrictive covenants and federally-sponsored mortgage discrimination kept both African Americans and Mexican Americans out of West Austin neighborhoods.33For restrictive covenants, see Eliot M. Tretter, Austin Restricted: Progressivism, Zoning, Private Racial Covenants, and the Making of a Segregated City (Report to the Institute for Urban Policy and Research Analysis, 2011); "Digital HOLC Maps," Urban Oasis, http://www.urbanoasis.org/projects/holc-fha/digital-holc-maps/, accessed November 15, 2013.

Despite segregation and unequal services, most accounts of African American and Latino life in Austin from the 1930s through the 1950s portray a generally positive period marked by high levels of community cohesion and a relatively vigorous economic life defined by small businesses and networks of familial and neighborhood support. Despite municipal negligence in nearly every aspect of life, segregation brought minority populations together and kept relatively high levels of economic diversity in Eastside neighborhoods.34See, for example, an interview with former Austin City Council member Charles Urdy in "East Austin Gentrification," Austin Now, KLRU, http://www.klru.org/austinnow/archives/gentrification/index.php, accessed August 31, 2011; Ben Wash, interview with the author, March 30, 2007; "Ben's Long Branch Bar-B-Q," Southern Foodways Alliance Southern BBQ Trail, http://www.southernfoodways.org/interview/bens-long-branch-bar-b-q/, accessed August 12, 2015; Anthony Orum, Power, Money and the People: The Making of Modern Austin (Austin: Texas Monthly Press, 1987), 184–186; "East Austin: Gentrification in Motion,"/Street (Oliver) Papers/Box 1/Folder 5/AHC. In 1951, there were over fifty black-owned businesses in the African American commercial corridors along Eleventh and Twelfth Streets.35J. Mason Brewer, A Pictorial and Historical Souvenir of Negro Life, Austin, Texas, 1950–1951: Who's Who and What's What (Austin, TX, 1950), courtesy BCAH, University of Texas at Austin.

Adding incentives to force minorities to the Eastside, the city improved segregated facilities during the 1930s, including funding a large public park, building a library, and improving all-black Anderson High School.36Orum, Power, Money, and the People, 192–194. Although public housing in Austin was strictly segregated and not intended to house the city's poorest residents, it was welcomed by minorities.37Ibid., 132–135. Yet major disparities in quality of life existed between East and West Austin. Minority residents were consistently subject to poorer, more dangerous living conditions, had less access to jobs and education, less mobility, were far more vulnerable to health problems, and were not considered part of mainstream economic, political, or social life in Austin.38Andrew M. Busch, "Building 'A City of Upper-Middle Class Citizens': Labor Markets, Segregation, and Growth in Austin, Texas, 1950–1970," Journal of Urban History 39, no. 5 (September 2013): 975–996.

Urban renewal projects dramatically altered the Eastside landscape during the 1960s. Until that point, the city held almost all power to determine the quality of structures, neighborhoods, or public facilities, providing Eastside residents with little input into the fate of their neighborhood. Language and images distributed by the Austin Urban Renewal Agency (AURA) assuaged what little opposition to urban renewal remained among Anglo Austinites.39Austin Urban Renewal Authority, "Slum Districts," (n.d., pamphlet)/Vertical File, "Austin, Texas—Industry (Cities)/BCAH; Elsworth Mayer, "5 Areas up for Urban Renewal," Austin in Action 7, no. 8 (March 1966); "Rx for Cities: Urban Renewal," (n.d., pamphlet)/Vertical File, "Austin, Texas—Industry (Cities)/BCAH. AURA simply needed to declare fifty percent of the structures in any given area "dilapidated beyond reasonable rehabilitation" or otherwise blighted in order to condemn the entire area. As the municipal government did not historically consider zoning important in East Austin, and since it was extremely difficult for minorities to acquire loans to buy or improve property, a large number of structures on the Eastside were deemed substandard.40Joe R. Feagin and Robena Jackson, "Delivery of Services to Black East Austin" (report to the University of Texas, n.d.); City of Austin Human Rights Commission, "Housing Patterns Study of Austin, Texas" (report, 1979), 123–171. All five major urban renewal projects in Austin affected the Eastside, and two focused exclusively on the Central Eastside neighborhoods of Kealing and Glen Oaks. The University of Texas used eminent domain laws to secure land in East Austin for a physical plant and new athletic facilities while dispossessing dozens of African American families. Large tracts of the central Eastside were razed; it is unclear exactly how many acres were redeveloped or residents dislocated, but as of June 1966, nearly one thousand acres were scheduled for clearance or rehab in East Austin; at least 250 of those acres were in central East Austin, a majority African American neighborhood.41"W. W. Collins to J. J. Pickle," June 7, 1966/Folder, "Urban Renewal Administration—Department of Housing and Urban Development"/Box 95-112-66/Papers of J. J. Pickle/BCAH. Well over one thousand residents were dislocated during this 1960s expansions, and many more were later relocated during the UT expansion in the 1980s.42Rudolph Williams, "Now is the Time for Justice!" Austin Chronicle, letter to the editor, June 12, 2007.

Most Eastside properties were not zoned residential; industry and commercial spaces were often interspersed with residential homes. Properties often had multiple uses, which also lowered their values. Absentee landlords often took advantage of weak municipal zoning and building code enforcement to let rental houses fall into disrepair. Infrastructure on the Eastside was practically non-existent; most residential streets remained unpaved into the 1960s and 1970s, and flooding remained a major concern well after that. Municipal investment was also scant. East Austin had far less park space than any other area of the city, as well as problems with street lights, garbage collection and informal dumps, and poor sidewalks.43Elizabeth J. Mueller & Sarah Dooling, "Sustainability and Vulnerability: Integrating Equity into Plans for Central City Redevelopment," Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 4, no. 3 (2011): 201–222. Page 208 discusses the difficulty of receiving loans for East Austin residents. See also City of Austin Human Rights Commission, "Housing Pattern Survey of Austin, Texas" (report, 1979); "The Life and Legacy of Mr. Oliver B. Street"/Street (Oliver) Papers/Box 1/Folder 1/AHC; Dale Carrington, "Mrs. Zamarripa say East Austin 'Victim of Poor Zoning,'" La Fuerza, April 11, 1974. For infrastructure see Carolyn Babo, "Land Owners Get 30-day Deadline to Clear Debris," Austin American, September 19, 1973; Brenda Bell, "Progress Moves Slowly," Austin Citizen, July 30, 1974; Patricia Yznaga, "East Austin: Let Me Show You the Streets," Daily Texan, November 21, 1979; Carrington, "Mrs. Zamarripa."

In the decades after urban renewal, the central Eastside endured a sharp and concentrated rise in poverty and crime, as residents of means moved further east and northeast. Although the neighborhood's central location gave residents access to many other areas, the central Eastside actually became more economically and socially segregated from the rest of the city after de jure segregation ended. A decade after urban renewal, poverty was still endemic to historically minority neighborhoods in central East Austin. In 1970, the central Eastside had a poverty rate of 37.5 percent. In 1977, 87 percent of central East Austin was deemed "low income" by the Community Development Block Grant application for that year.44City of Austin, "1977 Third Year Housing and Community Block Grant Application" (report, 1977), 32. By 1990, the rate of poverty had grown to 52 percent—in a city with one of the highest rates of economic growth in the United States during the 1980s and 1990s.45City of Austin Department of Planning, "Strategies for the Economic Revitalization of Central Austin," 25; 2007 Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Study of East Austin, "Austin, Texas: the East Austin Neighborhood," accessed on October 4, 2010, http://frbsf.org/cpreport/docs/austin_tx.pdf. Stats appear to be taken from census data. In 1988, for example, INC. magazine named Austin the best city for business in the United States; Census Information, "Changing African American Landscape—Eastern Core," http://www.austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/files/Planning/Demographics/ afam_change00_10_eastern_core.pdf, accessed August 12, 2015, demonstrates almost no concentrations of African American population in central Austin (between the Colorado River and US 183) of Interstate Highway 35 in 1990 or 2000. See for example, the neighborhood group East Austin Survival Task Force, "E.A.S.T Force: Urban Removal," which estimates drops in Latino residents in the neighborhood south of First Street beginning in the 1950s and continuing throughout the 1970s/Folder 27/Subject File, "Neighborhood Groups N1900"/AHC.

A steady increase in crime and poverty in central East Austin, especially in African American neighborhoods, was accompanied by an outmigration of minority citizens to other areas around the city. Between 1970 and 1976, Census Tract 8 in central East Austin, which was 97 percent minority, lost 1,976 residents and 446 families, a 14.8 percent decline in both categories.46City of Austin Department of Planning, "Strategies for the Economic Revitalization of Central Austin," (Preliminary Report, 1978), 19–20. Outmigration continued steadily throughout the 1990s as African Americans moved north and east from central East Austin. African American inmigration was almost non-existent in West Austin through 2000.47Census Information, "Changing African American Landscape—Eastern Core," demonstrates almost no concentrations of African American population in central Austin (between the Colorado River and US 183) of I-35 in 1990 or 2000. http://www.austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/files/Planning/Demographics/ afam_change00_10_eastern_core.pdf, accessed August 12, 2015. Real estate values in central Eastside neighborhoods also declined relative to the city as a whole. Even though overall values appreciated, in 1970 the median value of an owner-occupied unit in Census Tract 8 was 67 percent of the city average; by 1976 the median value was just 51 percent of the city average.48City of Austin Department of Planning, "Strategies for the Economic Revitalization of Central Austin," (Preliminary Report, 1978), 32. Finally, family income in central East Austin declined both in real dollars and relative to the city average between 1970 and 2000. In 1970 central East side median household income was 54 percent of the city's median household income. By 2000, the figure was down to 32 percent.49City of Austin Department of Planning, "Strategies for the Economic Revitalization of Central Austin," (Preliminary Report, 1978), 25; 2007 Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco study of East Austin, "Austin, Texas: the East Austin Neighborhood," http://frbsf.org/cpreport/docs/austin_tx.pdf, accessed October 4, 2010.

Demographic and economic data, as well as qualitative surveys, suggest that living conditions in central East Austin declined between 1970 and the 1990s.50K. Anoa Monsho, "From East Austin to East End: Gentrification in Motion," The Good Life (November, 2004)/Folder, "Text Materials"/Box 3/Austin Revitalization Authority Papers/AHC. Already a marginalized area, central East Austin underwent a process where residents of means, many local businesses, and jobs moved out; other residents were displaced; and little investment occurred. Austin's racial geography cut central Eastside residents off from jobs and equal education opportunities even as task forces and community development groups were funded by the city. By the mid-1990s, however, patterns of investment began to shift based on Austin's new focus on environmental sustainability and infill development. The city's business and political elites had encouraged suburban development to attract high tech white collar workers for decades and began efforts to claim central urban space under the same high tech banner in the 1990s.

Political Economic Transformation and the Reintegration of the East End

From the 1920s to the 1990s, the Eleventh Street Corridor and most of the central Eastside was essentially a city within a city, largely separate from greater Austin. As one journalist wrote in 1998, "it's the typical Eastside story, the reflex of a town that's been trained for years to see East Austin as a vast, one-dimensional alien ghetto from highway to horizon."51Mike Clark-Madison, "New Urban Sagas," Austin Chronicle, October 16, 1998. By the mid-1990s, however, political economic forces encouraging central city redevelopment in Austin proved too difficult for city leaders and development interests to ignore, and they sought to shift the geography of investment and development to central Austin in an effort to expand profit. Environmental and overdevelopment pressures, new international planning discourse, large perceived rent gaps, and the emergence of a policy dedicated to the cognitive-cultural economy52Allen J. Scott, "Capitalism and Urbanization in a New Key? The Cognitive-Cultural Dimension," Social Forces 85, no. 4 (June 2007): 1465–1482. Scott describes the cognitive cultural economy as one found in cities and defined by leading diverse sectors in high tech, neo-artisanal manufacturing industries, service functions, and cultural-products industries. This is one way Austin leaders and some scholars describe the city, and policies to nurture these sectors are prevalent in Austin. led Austin leaders to transform the urban landscape.

Austin developed rapidly during the postwar era of suburbanization's apogee. Lacking large industrial production facilities, the city's leading economic activities related to state government, the University of Texas, and increasing research and development, all of which employed a mostly white collar, middle class labor force. Because of zoning, ample space on the periphery, a paucity of public transportation, and perceived social benefits, development was almost exclusively suburban. Low density, single-use tract developments in the western and northern portions of the metro region dominated the housing market. Larger businesses that emerged during this period tended to locate in agglomerations on this urban periphery, including a science and research cluster anchored by the university's Balcones Research Center nine miles northwest of downtown. A series of regional shopping malls as well as smaller strip malls emerged. With the arrival and emergence of high tech firms, Austin's pace of growth increased markedly in the 1970s and 1980s.

Grassroots environmental groups emerged in the 1970s to promote responsible development as the built environment spread rapidly across outer Austin and over the Barton Creek Watershed and Edwards Aquifer, two important sources of drinking water, as well as leisure sites. In the following decade the citywide Save Our Springs Alliance (SOS) coalesced from numerous smaller neighborhood groups and the Austin Tomorrow public planning initiative. Outer suburbs were taking municipal resources away from more centrally-located middle class Anglo neighborhoods, and a new expressway threatened central western neighborhoods. The SOS Alliance sought to slow what they perceived to be rampant and environmentally damaging residential and commercial development in much of western Austin.53William S. Swearingen, Environmental City: People, Place, Politics, and the Meaning of Modern Austin (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010).

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, SOS fought bitterly with developers, and often the city, especially about proposed developments over the Edwards Aquifer Recharge Zone (EARZ), which fed Barton Springs and supplied much municipal drinking water. Contention grew to the extent that one journalist wrote, "since the beginning of the fight over water quality this town has been a battleground between real estate developers and those who would rather swim than shop."54Kayte VanScoy, "Bonding over the Bonds: Council's Dreams come True," Austin Chronicle, May 8, 1998, http://www.austinchronicle.com/news/1998-05-08/523430/. Suburban tract developers saw the land over the aquifer as prime because of its natural beauty, location on the edge of the Hill Country region, and proximity to Austin's information technology agglomeration to the northwest. Following referendums forced by SOS in 1991, the city passed a series of zoning ordinances making development over the aquifer more difficult. Battles between environmentalists and developers, led by the Real Estate Council of Austin, ensued over the next five years. By 1997, the city had elected the "Green Council," made up of longtime Austin environmentalists, with Kirk Watson as mayor. Austin environmentalist and author William Swearingen sees this election as the moment when quality of life advocates finally and convincingly dispatched the development-oriented growth coalition, saving the city's sense of place from destruction while ensuring responsible growth.55Swearingen, Environmental City, 164–174.

Mayor Watson and his city council began a campaign for "smart growth," an urban planning movement endorsed by President Clinton that encouraged blending quality of life with environmental protections and economic development initiatives. The smart growth movement in city and regional planning was an attempt to create policies that promoted and rewarded the implementation of New Urban designs: pedestrian-friendly, mixed use, transit-oriented, filled with open spaces, and humanly scaled.56Andres Duany, Jeff Speck, and Mike Lydon, The Smart Growth Manual (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010). The American Planning Association adopted its principles following the UN Conference on Environment and Development in 1992. In Austin, smart growth was understood as a means to protect the environment as a place of beauty and recreation while mitigating, but not destroying, economic and demographic growth by directing it into already-existing areas.57In the 1970s the public planning initiative Austin Tomorrow designed a development plan that attempted to funnel growth to the north and south of the existing city rather than expand east and west. The plan was never adopted into law.

The most immediate concern for Watson was protecting undeveloped land in the hills west of Austin, which would preserve Barton Springs, control development over the aquifer, and assuage concerns from environmentalists. With development curtailed along much of city's western periphery, the council outlined a Smart Growth Initiative (SGI) to transform the central Eastside using New Urbanist principles. As part of the new Desired Development Zone (DDZ), a centrally located section of the city that was already largely built and could manage higher levels of density, the central Eastside would benefit from tax breaks, subsidies, and infrastructural improvements designed to make development more attractive and promote investment. The incentives were a boon for developers who now had less access to the upscale western suburbs.

The central Eastside also had economic advantages associated with the geography of gentrification, large discrepancies (called rent gaps) between the existing and potential value of property. The idea of a rent gap was proposed by geographer Neil Smith in 1979 to explain why gentrification occurs. Smith proposed that once ground rents (or real estate prices) get low enough in an area relative to potential ground rents, developers, profit-seeking individuals, and real estate interests will purchase land in that area and perhaps refurbish the property to close the rent gap. Since areas close to city centers have relatively high potential ground rents and very low existing ground rents, the potential for profit is high in centralized, dilapidated neighborhoods where property is cheap. Municipalities often incentivize redevelopment in such areas because they can collect more taxes from property that is worth more; this is significant in Austin where valuable, centrally-located property is occupied by the state government and university—entities that pay no property tax.58Neil Smith, "Towards a Theory of Gentrification: A Back to the City Movement by Capital, not People," Journal of the American Planning Association 45, no. 4 (October 1979): 538–548

In the late 1990s and into the new millenium, Austin political leaders devised a growth strategy to attract the "creative class," knowledge workers that would be attracted to the amenities, cultural opportunities, and lifestyles associated with the urban core.59Carl Grodach, "Before and After the Creative City: The Politics of Urban Cultural Politics in Austin, Texas," Journal of Urban Affairs 34, no. 1 (2012): 81–97. For more on the creative class, see Richard Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class: And how it's Transforming Work, Leisure, Community, and Everyday Life (New York: Basic Books, 2002). The city passed a $712 million bond package in 1998, most of which was directed at improving infrastructure, flood control, and creating economic incentives for businesses relocating to the DDZ.60Mike Clark-Madison, "Bonds Election Cliffs Notes," Austin Chronicle, October 23, 1998; "Naked City," Austin Chronicle, November 13, 1998; Jenny Staff, "Speed Up with Downtown," Austin Chronicle, December 11, 1998. By early 1999 the city approved two large scale high tech relocations to the downtown area; the city also approved plans for a live-work-play condominium complex adjacent to one of the office and research facilities and initiated a cultural facelift by fast tracking new bars, restaurants, shops, and clubs. The new downtown would cater to the urban tastes of the creative class.61Dulan Rivera and Bill Bishop, "High Tech Companies Leading the Charge Downtown," Austin American Statesman, March 3, 2000/Vertical File, "Austin, TX—Neighborhoods and Neighborhood Groups (2—misc.)"/BCAH; Kevin Fullerton, "If You Build it . . . What Dreams May Come," Austin Chronicle, February 5, 1999. Smaller high tech firms used incentives to relocate to the central Eastside near the Eleventh Street corridor as well, and a number of small multi-use condo complexes arose on the Eastside south of Eleventh Street from 2000 to 2006. Real estate values, ground rents, and property taxes spiked adjacent to these new developments, and property values were affected dramatically in the entire neighborhood.62Barbara Wray, "Developers, Builders now Look to East Austin," Austin Business Journal, December 3, 2000; Welles Dunbar, "How Not to Gentrify: HRC Asks for Eastside Moratorium," Austin Chronicle, November 4, 2005; Diana Welsh, "Naked City," Austin Chronicle, April 8, 2005; Ryan Robinson, "Income and Neighborhood Planning Areas," 2006, http://www.ci.austin.tx.us/demographics/downloads/income_npas_collection.pdf, accessed December 18, 2014.

New Urbanism and New Urbanity in Austin

New Urbanist architecture and its legal accouterments—mixed use zoning and historical preservation—projected Austin's new urbanity, catering mostly to white, upper middle class preferences and erasing aspects of the older urbanity. Sharon Zukin has argued that the urban "symbolic economy" operates by making certain groups feel unwelcome in some spaces while appealing to the taste of others.63Zukin, The Culture of Cities, 3–15. Symbols of change can force community groups to focus more on defending their neighborhoods than on improving them. Why was New Urbanism such a potent symbol of gentrification for residents in East Austin, and why did it mark space for upscaling and demographic transformation?

New Urbanism has drawn criticism for reproducing elite landscapes even as it articulates the importance of mixed income developments. Prototypical new urban "towns," such as Seaside and Celebration (both in Florida), evoke traditional architectural styles that reflect social and economic exclusion by reproducing a romanticized version of the traditional human-scale town of the late nineteenth century: walkable, denser than single-use suburbs, and with lots of public space. But they tend to be socioeconomically exclusive and racially homogenous.64Celebration, Florida, for example had a median family income of $92,334 and was 1.5 percent African American in 2010. "Celebration CDP, Florida," accessed March 18, 2015, http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/12/1211285.html. According to Neil Smith, New Urbanist architectural style located in certain public spaces can both create and mimic sanitized suburban aesthetics.65Neil Smith, "Which New Urbanism? The Revanchist 90s," Perspecta 30, Settlement Patterns (1999): 98–105. Residents do not have to drive to upscale malls to shop; the same boutiques are accessible by foot.

At its core mixed use zoning is an aesthetic change. Unlike older neighborhoods, where properties were developed and redeveloped independently over time, New Urban developments are usually comprehensively planned and developed in the same style. They give the appearance of being dropped into an existing landscape because they are built all at once. In a sense they are removed from their surroundings, not a part of the urban fabric as much as an island within it. "Within the design concepts and site plans of new urbanism," argues Smith, "the world can be made safe for a self-conscious liberalism."66Ibid., 104. New Urbanism allows predominately white residents to feel progressive, urbane, and environmentally friendly while providing the security and exclusivity associated with suburban living.

New Urbanism in Austin focused on redevelopment and increased economic activity, functioning in the city's larger gentrification narrative to influence decisions about what needs to be removed and what can stay or be redeveloped. "Urban decline, street crime, and 'signs of disorder,'" continues Smith, "are here galvanized into a single malady." The entire landscape must be "sanitized."67Ibid., 100. Unattractive buildings, criminals, homeless people, and poor residents are all subject to erasure. In Austin, new urbanity has included a strong increase in the policing of homeless populations, particularly downtown and on the central Eastside. While crime has dropped dramatically in the East Eleventh Corridor since redevelopment began, the range of people who have access to public space there has also been severely curtailed. Who can consume in upscale boutiques and restaurants given the average income level of long-term neighborhood residents? Redevelopment often expresses revanchist notions of race and class associated with urban renewal in cities like New York and Los Angeles.68Ibid; Neil Smith, The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City (New York: Routledge, 1996); Mike Davis, City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles (New York: Vintage Books, 1992). One Eastsider summed up the tone by writing that supporters of New Urbanism had "put droves of Austin 'people' on the 'endanger/extinct' list" by forcing them from targeted areas.69Rick Hall, letter to the editor, "Economic Cleansing," Austin Chronicle, April 2, 1999.

The increasing price of real estate and land in the developed areas and adjacent properties constitutes perhaps the most obvious way New Urbanism sets gentrification in motion. A recent study by the Urban Land Institute found that New Urban design alone can raise real estate prices dramatically.70Mark J. Eppli and Charles, C. Tu, Valuing the New Urbanism: The impact of the New Urbanism on Prices of Single Family Homes (Washington, DC: Urban Land Institute, 1999). Property taxes also rise too quickly and dramatically for marginalized residents to endure. In 2004 a Human Rights Commission study found that approximately 70 percent of foreclosures in Austin occurred on the Eastside and recommended a ninety-day moratorium on new projects.71In 2000 approximately 15 percent of Austin residents lived on the Eastside; less than half of those lived on the central Eastside. Dunbar, "How Not to Gentrify." A University of Texas study found that land values in one Eastside neighborhood, which housed a high concentration of the city's New Urban projects, rose 400 percent between 1998 and 2004. Property taxes increased by 123 percent.72Dunbar, "How Not to Gentrify." The average housing cost in the central Eastside rose 250 percent between 2000 and 2007, from $77,000 to $195,000.73 Katherine Gregor, "Developing Stories," Austin Chronicle, November 9, 2007. Even housing deemed affordable in transitional neighborhoods often excluded working class Eastside families. In 2005, the affordable housing baseline was set at $56,000, 80 percent of Austin's median household income; the average household income among minorities in Austin was roughly half that in 2000.74Amy Smith, "Eddie on the East Side: HB 525," Austin Chronicle, March 4, 2005. Racial change was obvious as real estate values and property taxes increased; between 2000 and 2010 the proportion of minority residents declined by at least 15 percent in every neighborhood on the central Eastside. "Austin's Smart Growth planning is a land grab," protested a letter writer to the Austin Chronicle, "a purge of lower income Austinites" from their traditional neighborhoods.75Rick Hall, "Austin's War on the Poor," Austin Chronicle, December 29, 2000.

Long term residents of the central Eastside were keenly aware that New Urbanism would likely fracture their neighborhoods, and they often pointed to existing examples of displacement. As precedent, Rudolph Williams, president of the Organization of Central East Austin Neighborhoods (OCEAN) discussed the appropriation of East Austin space by the University of Texas in the 1980s. He pointed to the "development of high-rent condos and townhomes encircling our neighborhoods" as evidence of the forces that were pushing the "minority community" further east.76Rudolph Williams, letter to the editor, "Now is the Time For Justice!" Austin Chronicle June 12, 2007. Latina activists also associated new urban architecture with gentrification. People in Defense of Earth and her Resources (PODER) leader Susana Almanza had a similar understanding of the new condominium/retail complexes characteristic of New Urbanism: "PODER and generations of Mexican-American residents did not ask for the development of new condos or lofts" on the Eastside. Residents in Eastside neighborhoods signed petitions against new zoning measures that allowed for commercial mixed use zoning characteristic of New Urbanist development.77Susana Almanza, letter to the editor, "Speaking Up," Austin Chronicle, December 2, 2005. Other Eastsiders felt the new businesses represented transformation and displacement. One wrote that, "Most of these projects cater to affluent, white, young professionals. The housing units (aka condos and lofts) are overpriced, and the small coffee shops and businesses (art galleries) don't appeal to us because they were not made to serve us."78Ana Vilalobos, letter to the editor, "In Favor of PODER," Austin Chronicle, December 2, 2005. "Smart Growth equals gentrification," wrote another. "If it didn't it wouldn't work!"79David Smith, letter to the editor, "Grow Up Austin," Austin Chronicle, October 22, 1999. Activists identified consumption opportunities as a key aspect of gentrification and recognized that new businesses were not intended to serve long-term residents.

Local commentators recognized that zoning rules allowing for New Urban development and historic preservation were essential aspects of urban transformation and the greatest threat to neighborhood cohesion.80Welles Dunbar, "Zoned Out," Austin Chronicle, February 8, 2008. They were also the city's best tools for creating a lucrative redevelopment landscape. By 2004, Austin had the most generous subsidies for historically zoned (H-Zoning) properties of any US city, offering large tax abatements for residential and commercial properties.81Mike Clark-Madison, "New Rules for Old Buildings: The Historic Tax Force," Austin Chronicle, April 2, 2004. PODER leaders and neighborhood residents understood historic preservation zoning as a strategy that favored buildings over people and linked tax abatements to intensified gentrification. Anita Quintanilla pointed to the irony of her former neighborhood becoming nicer and the building of a Mexican American Culture Center occurring "at the same time that the Mexican community is being torn apart and pushed out due to gentrification."82Anita Quintanilla, "Cultural Center of their Own," Austin Chronicle, December 2, 2005. Almanza's work persuaded the city to create a task force which found that H-Zoning engendered gentrification by increasing values and costs, but it forestalled gentrification by preventing demolition of buildings and preserving neighborhood character. By imagining gentrification as primarily affecting buildings, the task force made Almanza's point more obvious.83Brant Bingamon, "PODER vs. H-Zoning: Ready for Round Two?" Austin Chronicle, November 1, 2002; Brant Bingamon, "Old Homes = New Yuppies?"Austin Chronicle, July 19, 2002.

Residents also felt that Vertical Mixed Use (VMU) zoning changes became instruments of gentrification. The key zoning type the city developed as part of the Smart Growth Initiative was VMU, which legalized mixed use condo/retail/office space in areas of the desired development zone. As Austin planning commissioner Ben Heismath announced in 1999, "'density' isn't the bad word it was five years ago." But in most of Austin, Heismath claimed, "urbanity in building is against the law."84Mike Clark-Madison, "Mapping the Future," Austin Chronicle, December 3, 1999. Suburban style subdivisions with neighborhood associations in West Austin made mixed-use illegal. Here neighborhood plans kept density levels low to ensure a preponderance of single family homes in single use residential neighborhoods. But in central East Austin rezoning property was key to increasing density and property taxes. PODER leaders were acutely aware of the relationship between increased density, mixed use zoning, and gentrification, and they fought against zoning changes that allowed for densification at every opportunity.

Spatial Justice, Sustainability, and the Possibilities for Inclusive Neighborhood Development

Municipally-sponsored gentrification in Austin must be understood as the latest manifestation of spatial injustice rather than as a new phenomenon. Since the early twentieth century racial segregation and the control of minority populations through land use has characterized much policy and practice. Municipal authorities moved minorities around the city in ways that benefitted white citizens, the University of Texas, and the interests of capital accumulation. The social segregation of the early twentieth century gave way to institutionally-motivated segregation and removal in the post-WWII decades. Over the last two decades gentrification has created a third type of segregation, characterized by displacement rather than containment and by accumulation through dispossession rather than though social and institutional discrimination. Neighborhoods suffering from socioeconomic as well as spatial discrimination are fracturing as they become too expensive for longtime residents. Austin has heavily invested in remaking the Eastside for private investment but has done little to mitigate the negative externalities that undermine neighborhood cohesion and support structures for vulnerable residents.

The return of capital to the Eastside reflects an Austin image propagated by developers, environmentalists, and city officials, each with distinct but related reasoning. The concept of sustainability has become a driving force in Austin's development and is related to its increasing prominence as a livable, prosperous, and desirable metro region in an era of increasing competition for investment. Recent city planning literature has pointed to sustainability as a hallmark of Austin's attractiveness and as an important part of quality of life for residents—so much so that "'sustainability' [is] the central policy direction of the ImagineAustin Comprehensive Plan."85See for example, page seven of the Imagine Austin Comprehensive Plan, adopted by the Austin City Council on June 15, 2012. The plan acknowledges Austin's racial history (not racial geography), but views sustainability primarily as an environmental/resource issue. The inner city is marketed as prime recreational and commercial space for younger adults and creative workers, and spaces of consumption are more upscale and varied. The region's robust business and demographic growth, even during recent global downturns, speaks to its sustainability as an emerging metropolis. For environmentalists, sustainability indicates an increasing quality of life via protected natural spaces and water, as well as the related effort to increase density and green building in the urban core. They are also invested in Austin's image and in the benefits of having a larger number of natural spaces integrated into the urban fabric or a short distance away. The Austin Recreation Commission slogan signals this ideal: "Cultural Places, Natural Spaces."

The new spatial arrangements in Austin do not account for the needs of all neighborhoods and populations, however. Gentrification is about much more than housing. It is the leading edge of a municipally-sponsored new urbanity, where the central city is remade to attract people who consume more, pay more taxes, and desire urban lifestyles. New Urbanism provides a complementary architecture imagined as environmentally sustainable and properly dense, walkable, reliant on mass transit, and close to downtown. Issues of sustainability, however, are rarely imagined as applying to poor and working class populations of Austin.

Since the 1970s the federal government has moved towards privatized, market-based models to meet the demand for low income housing. Little federally-subsidized public housing has been built.86Edward G. Goetz, New Deal Ruins: Race, Economic Justice, and Public Housing Policy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2013). Historically, private developers have failed to meet market demands for low income housing in Austin.87Busch, "Building 'A City of Upper-Middle Class Citizens.'" Cities are increasingly forced to create solutions to shortages but are also dedicating more resources to attracting investment than ever before. Gentrification is often an outcome of this entrepreneurial urban policy. So, how can the city protect and empower those threatened by rising costs associated with gentrification? How can it create more equitable housing policies and subsidize low income participation? What can be learned from other cities? In New York City, rent stabilization and vouchers have helped to mitigate the negative effects of gentrification.88Elvin Wyly, Kathe Newman, Alex Schafran, and Elizabeth Lee, "Displacing New York," Environment and Planning A 42, no. 11 (2010): 2602–2623. In Portland, community forums give voice to vulnerable residents coping with gentrification and provide a space for dialogue between long-term residents and newcomers.89Emily M. Drew, "Listening through White Ears: Cross Racial Dialogues as a Strategy to Address the Racial Effects of Gentrification," Journal of Urban Affairs 34, no. 1 (2012): 99–115.

In Austin, the city offered to subsidize developers who included lower cost units in their buildings, but the subsidies failed to match the profit developers could make by charging full price for each unit.90Mike Clark-Madison, "Naked City," Austin Chronicle, July 30, 2000, http://www.austinchronicle.com/news/2000-06-30/77787/; Dunbar, "How Not to Gentrify." In some new Eastside developments the city has subsidized low income residents with taxes on big box stores, but those rarely help the poorest residents. Perhaps the city should take a more direct approach to managing dislocation. What if it froze property taxes for qualified residents in areas undergoing rapid appreciation? Gentrification has greatly increased tax revenues on the Eastside, but the city as a whole has seen nearly 40 percent average increases in property taxes since 2008.91James Quintero, "Austin Homeowners See Continued Property Tax Increases" (report for the Texas Public Policy Foundation, August 12, 2014), http://www.texaspolicy.com/center/local-governance/blog/austin-homeowners-see-continued-property-tax-increases. Austin is also one of the fastest growing US cities, with 3 percent population growth and a staggering 6.3 percent growth in its economy in 2012, the best among the 102 largest US markets.92See, for example, Morgan Brennan, "America's Fastest Growing Cities," Forbes, January 23, 2013. Forbes named Austin its fastest growing city in 2012. See also Greg Barr, "Austin's Economy Named No. 1 in the Country," Austin Business Journal, October 24, 2013. This rate of growth puts the city in a position to assist vulnerable residents with tax freezes, rent control measures, or subsidies for rental assistance.

African Americans have lost population share in Austin every decade since 1920 and experienced decline from 2000 to 2010, even as the city as a whole grew by 20 percent. Austin is one of the few metro regions in the US with a higher percentage of African Americans in suburbs than in the central city—and poverty in Austin's suburbs rose by 143 percent between 2000 and 2011, the second fastest increase in the US. Urban African American household incomes continue to lag, averaging only half the household income of whites. The city as a whole has a poverty rate of around 23 percent; a majority of those in poverty are people of color. In some Eastside neighborhoods, poverty is 2000 percent greater among African Americans than among whites.93"Austin, Texas (TX) Poverty Rate Data: Information about Poor and Low Income Residents," http://www.city-data.com/poverty/poverty-Austin-Texas.html, accessed July 15, 2013. For suburban poverty, see "Study: Poverty in Austin Suburbs Rises Sharply," accessed July 15, 2013, http://www.keyetv.com/template/cgi-bin/archived.pl?type=basic&file=/news/features/top-stories/stories/archive/2013/05/45blYPXT.xml#.UeQgg5Z32ZQ. These statistics indicate that, despite economic growth and an overall strong quality of life, Austin is not a particularly sustainable place for its historically disadvantaged residents. Socioeconomic bifurcation results from historical discrimination and a political geography that aligned minorities with undesirable urban functions and spaces. As urbanity becomes popular in Austin, the people long associated with negative urbanism are forced out. Austin's politicians, planners, and business elites must recognize that preserving and sustaining disadvantaged communities, and not just their buildings and spaces, needs to be central to any meaningful sustainability agenda. Unless policy changes it is likely that significant displacement will continue.

About the Author

Andrew M. Busch is visiting assistant professor of American studies at Miami University (Ohio). In 2011, he received his PhD from the University of Texas at Austin. His current project, "City in a Garden: Race, Progressivism, and the Environment in Making Modern Austin, Texas," investigates the development of Austin, Texas, and the ways that ideologies of the natural and the urban shaped the race and class geography of the city. The manuscript is under contract with the University of North Carolina Press. His future projects include a study of the relationship between urban renewal and gentrification and a book on environmental inequities in the American South.

Recommended Resources

Text

Barna, Joel Warren. "The Rise and Fall of Smart Growth in Austin." Cite 53 (2002): 22–25. http://offcite.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2010/03/ TheRiseAndFallOfSmartGrowthInAustin_Barna_Cite53.pdf.

Cantú, Tony. "Eastward Expansion: Real Estate Prospecting on the Eastside." Austin Chronicle, April 10, 2015. http://www.austinchronicle.com/news/2015-04-10/eastward-expansion/.

Congress for the New Urbanism. Charter of the New Urbanism. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000.

Duany, Andres, Jeff Speck, and Mike Lydon. The Smart Growth Manual. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010.

Grodach, Carl. "Before and After the Creative City: The Politics of Urban Cultural Politics in Austin, Texas." Journal of Urban Affairs 34, no. 1 (2012): 81–97.

Katz, Peter. The New Urbanism: Towards an Architecture of Community. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994.

Long, Joshua. "Constructing the Narrative of the Sustainability Fix: Sustainability, Social Justice, and Representation in Austin, Texas." Urban Studies (December 2014): 1–24.

McCann, Eugene J. "Inequality and Politics in the Creative City-Region: Questions of Livability and State Strategy." International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 31, no. 1 (March 2007): 188–196.

Mueller, Elizabeth J. and Sarah Dooling. "Sustainability and Vulnerability: Integrating Equity into Plans for Central City Redevelopment." Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 4, no. 3 (2011): 201–222.

Smith, Neil. "Which New Urbanism? The Revanchist 90s." Perspecta 30 (1999): 98–105.

———. The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City. New York: Routledge, 1996.

Skop, Emily. "Austin: A City Divided," in The African Diaspora in the United States and Canada at the Dawn of the 21st Century, edited by John Frasier, Joe T. Darden, and Norah F. Henry. New York: Academic Publishing, 2009.

Solomon, Dan. "Demolished East Austin Piñata Shop Is the New Center of Austin's Gentrification Debate." Texas Monthly. February 2015. http://www.texasmonthly.com/daily-post/demolished-east-austin-pi%C3%B1ata-shop-new-center-austins-gentrification-debate.

Tang, Eric, and Chunhui Ren. Outlier: The Case of Austin's Declining African American Population. Austin: University of Texas Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis, 2014.

Tretter, Eliot M. "Contesting Sustainability: 'SMART Growth' and the Redevelopment of Austin's Eastside." International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37, no. 1 (January 2013): 297–310.

Web

"Austin Revealed," Many Rivers to Cross. KLRU. 2013. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/partner-content/partner-content-klru-austin/.

Civic Summit. "East Austin Revealed." KLRU. 2014. http://www.klru.org/episode/civic-summit/east-austin-revealed/.

Emery, Michael. "East Austin Gentrification." Spotlight Report: Austin NOW. KLRU. http://www.klru.org/austinnow/archives/gentrification/.

Ramirez, Elena. "The Women of PODER have Empowered East Austin to Fight Injustice." Spotlight Report: Austin NOW. KLRU. http://www.klru.org/austinnow/archives/PODER/PODER.php.

Zehr, Dan. "Inheriting Inequality." Austin American-Statesman. 2014. http://projects.statesman.com/news/economic-mobility/index.html.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Much of the early history of the ARA was marred by questionable real estate practices and stacking of the ARA board by councilman Eric Mitchell and his group of connected developers and politicians. Mitchell did not include any neighborhood representatives on the first ARA board. See A. D., "ARA Board Member Helps Himself," Austin Chronicle, January 12, 1996, http://www.austinchronicle.com/news/1996-01-12/530368/; Mike Clark-Madison, "The ARA Myth: Empty Promises on the Eastside," Austin Chronicle, June 20, 1997, http://www.austinchronicle.com/news/1997-06-20/529133/. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Crone Urban Design Team, "New Visions of East Austin: Central East Austin Master Plan," Report, 1999, courtesy AHC. |

| 3. | Ryan Robinson, "Top Ten Demographic Trends in Austin, Texas," http://www.austintexas.gov/page/top-ten-demographic-trends-austin-texas, accessed December 18, 2014. Robinson is the city's demographer. |