Overview

Robert Goddard reviews Matthew Mulcahy's Hubs of Empire: The Southeastern Lowcountry and British Caribbean (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014).

Review

|

Any historical account requires a framing device—temporal, thematic, or geographical—establishing the scope of enquiry. A Caribbean history typically invokes fairly settled geographical parameters that delimit the area to insular territories of the Caribbean Sea, with occasional forays into the Guianas and Suriname. While a geographical imaginary can be intuitive and helpful, this emphasis on the Caribbean Sea sometimes obscures meaningful continuities. William Faulkner, for example, influenced iconic Caribbean writers Derek Walcott and Édouard Glissant and also made a pronounced impact on South American writer Gabriel García Márquez.1Valérie Loichot, Orphan Narratives: The Postplantation Literature of Faulkner, Glissant, Morrison, and Saint-John Perse (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2007). It is salutary to occasionally violate these framing devices—their utility notwithstanding—in the interest of restoring obscured linkages and connections.

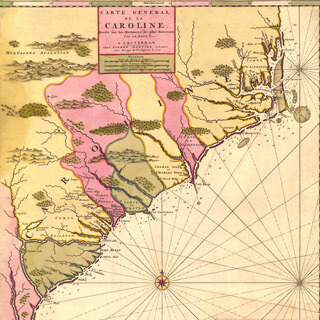

Matthew Mulcahy's Hubs of Empire: The Southeastern Lowcountry and British Caribbean does precisely this, presenting what became Carolina rice country as part of the Anglophone Caribbean's plantation zone. The founding of a settlement that became Charleston, South Carolina, by a group of planters from Barbados in the 1670s functions as the analytical core of the book. This migration between the British Caribbean and the Lowcountry establishes important continuities as the Barbadians brought with them their slaves, planting practices, capital, and racial ideologies.

This is not an entirely novel project, as the links between the Caribbean and the Carolinas are well known; systematic analyses of these connections date at least to Jack Greene's Barbadian cultural hearth thesis from the 1960s.2Jack P. Greene, "Colonial South Carolina and the Caribbean Connection," in Jack P. Greene, Imperative Behaviors and Identities: Essays in Early American Cultural History (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1992), 68–86. Neither is Mulcahly's the only recent book on the subject, joining Paul Pressly's excellent On the Rim of the Caribbean.3Paul M. Pressly, On the Rim of the Caribbean: Colonial Georgia and the Atlantic World (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2013). But Hubs of Empire is a remarkably well-accomplished synthesis. To successfully undertake a project of this kind requires mastering a vast secondary literature on the ecology of the area, its pre-Columbian traces, imperial rivalries between Spain, France, and Great Britain, alongside an understanding of the origin and evolution of the plantation system and its attendant slave societies. And to do a thorough job, one cannot ignore the endless and sometimes intense debates that both inform and deform historical interpretation. All this Mulcahy does superbly: he surveys these literatures comprehensively and presents the historiographies nimbly and with admirable balance. In particular, Mulcahy addresses several controversial topics in a clear and balanced way, among them the introduction of rice culture to the Carolinas. One group of scholars argues that African slaves imported to the Lowcountry had prior knowledge of rice culture and it was this expertise that made possible the plantation society of the Carolina Lowcountry. Another group has examined the empirical evidence and finds no evidence that the slaves imported to the Lowcountry came from rice-growing areas of Africa. Central to this controversy are issues of ideology and method that animate research in Atlantic World Studies: were slaves merely the passive objects of history or did they actively shape their own destinies?4David Eltis, Philip Morgan, and David Richardson, "Agency and Diaspora in Atlantic History: Reassessing the African Contribution to Rice Cultivation in the Americas," American Historical Review 112, no. 5 (2007): 1329–1358; Walter Hawthorne, "From 'Black Rice' to 'Brown': Rethinking the History of Risiculture in the Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Atlantic," American Historical Review 115, no. 1 (2010): 151–163. Mulcahy finds a middle ground between these starkly different explanations for the origins of rice culture, one that documents contributions from both Africa and Europe in a way that strikes me as balanced yet well supported by the evidence.

|

| Barbados, South Carolina, USPS The American Revolution Bicentennial commemorative stamp, 1976. © United States Postal Service. |

By reframing the history of coastal Carolina, Mulcahy succeeds in rendering "both the Lowcountry and the islands less anomalous within the larger context of colonial British America" (8). This is a very important contribution and helps balance typical presentations of US history that tend to interpret colonial history as the inevitable springboard to the formation of the United States.5Jack P. Greene, "Colonial History and National History: Reflections on a Continuing Problem," William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, 64, no. 2 (January 1, 2007): 235–250. Adopting this Greater British Caribbean frame, Mulcahy shows how Carolina rice culture was more Caribbean than Virginian: the Carolinas and the Caribbean were characterized by larger plantations, wealthier planters, more imbalanced ratios of whites to blacks, and deadlier disease environments than tobacco plantations further north. Mulcahy is also scrupulous enough to note important differences between the Carolinas and the Caribbean: the task system of labor organization central to rice plantations marks a salient distinction to the gang labor system of the sugar islands.

Although Hubs of Empire is excellent, I would have liked for Mulcahy to extend his temporal frame. His narrative covers the early colonial period to the American Revolutionary War. There are good reasons for doing this, especially as Mulcahy describes the coastal Carolinas and the English islands as the Greater British Caribbean. After 1776, the Carolinas joined the American bid for independence while the islands did not. Another reason for this is the book's inclusion in the series Regional Perspectives on Early America put out by Johns Hopkins University Press. But the cultural continuities between the Carolinas and the Caribbean continued well after US independence, begging for an extended analysis through the fall of plantation agriculture in the decades following World War II. The coastal stretch from Savannah to Wilmington remains, even today, quite different from the adjacent piedmont.

|

| Slaves of the Rebel General Thomas F. Drayton, Hilton Head, South Carolina, 1862. Photograph by Henry P. Moore. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-04324. |

Since the 1790s, The piedmont has been dominated by an ethos shaped by Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian strains of Protestant belief that eschew drinking, card playing, gambling, and other activities considered outside the realm of Christian behavior.6Charles Reagan Wilson, "Overview: Religion and the US South," Southern Spaces, March 16, 2004, https://southernspaces.org/2004/religion-and-us-south/. The coastal areas, in contrast, seem to embrace a more Caribbean manner, where social life readily includes alcohol. The architectural styles of the Caribbean and coastal Carolinas offer other important points of comparison, shaped by similar environmental constraints that exercise powerful influence on modes of living and organizing space. Even linguistically, the cultural continuities between the British Caribbean and the Carolina coast warrant further examination. Mulcahy notes that "the development of pidgin and creole languages occurred throughout the region" and that the "ongoing importance of African languages and the distinct creole languages that emerged over time was yet another factor distinguishing slave culture in the Greater Caribbean from the Chesapeake" (134). There is a respectable body of opinion that supports Mulcahy's larger thesis in arguing that Gullah did not develop autonomously but was rather an outgrowth of creole imported into Carolina as part of the migration from Barbados in the late 1600s.7See Frederic G. Cassidy, "Barbadian Creole: Possibility and Probability," American Speech 61, no. 3 (Autumn, 1986): 195–205. Cassidy's view is challenged by Ian F. Hancock, "Gullah and Barbadian: Origins and Relationships," American Speech 55, no. 1 (Spring, 1980): 17–35.

Overall this is a fine book: balanced, comprehensive, and well written. The story of colonial America needs to be reinserted into its original context, that of the Atlantic World. Later continental ambitions, encapsulated in the term "Manifest Destiny" have produced a distorting lens for the understanding of early America. The use of texts like Hubs of Empire is critical to the recuperation of this historical experience shared alike by what became the United States and its Caribbean neighbors in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

About the Author

Robert Goddard is senior lecturer and director of the Latin American and Caribbean Studies Program at Emory University.

Recommended Resources

Text

Greene, Jack P. Imperatives, Behaviors, and Identities: Essays in Early American Cultural History. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1992.

Pressly, Paul M. On the Rim of the Caribbean: Colonial Georgia and the Atlantic World. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2013.

Rushforth, Brett and Paul Mapp. Colonial North America and the Atlantic World: A History in Documents. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009.

Web

Barbados and the Carolinas Legacy Foundation. http://www.barbadoscarolinas.org.

Caribbean Studies Association. http://www.caribbeanstudiesassociation.org.

"On the Water: Living in the Atlantic World, 1450–1800." Smithsonian National Museum of American History. http://amhistory.si.edu/onthewater/exhibition/1_1.html.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Valérie Loichot, Orphan Narratives: The Postplantation Literature of Faulkner, Glissant, Morrison, and Saint-John Perse (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2007). |

|---|---|

| 2. | Jack P. Greene, "Colonial South Carolina and the Caribbean Connection," in Jack P. Greene, Imperative Behaviors and Identities: Essays in Early American Cultural History (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1992), 68–86. |

| 3. | Paul M. Pressly, On the Rim of the Caribbean: Colonial Georgia and the Atlantic World (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2013). |

| 4. | David Eltis, Philip Morgan, and David Richardson, "Agency and Diaspora in Atlantic History: Reassessing the African Contribution to Rice Cultivation in the Americas," American Historical Review 112, no. 5 (2007): 1329–1358; Walter Hawthorne, "From 'Black Rice' to 'Brown': Rethinking the History of Risiculture in the Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Atlantic," American Historical Review 115, no. 1 (2010): 151–163. |

| 5. | Jack P. Greene, "Colonial History and National History: Reflections on a Continuing Problem," William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, 64, no. 2 (January 1, 2007): 235–250. |

| 6. | Charles Reagan Wilson, "Overview: Religion and the US South," Southern Spaces, March 16, 2004, https://southernspaces.org/2004/religion-and-us-south/. |

| 7. | See Frederic G. Cassidy, "Barbadian Creole: Possibility and Probability," American Speech 61, no. 3 (Autumn, 1986): 195–205. Cassidy's view is challenged by Ian F. Hancock, "Gullah and Barbadian: Origins and Relationships," American Speech 55, no. 1 (Spring, 1980): 17–35. |