Overview

In this online exhibition catalog, Dorothy Moye presents and comments upon the textile art of Gwendolyn Ann Magee (1943–2011). This catalog accompanies the exhibition at the Gatewood Gallery of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (September 11–November 8, 2014). Magee's extraordinary work includes a series of vivid, often harrowing, narrative quilts based on James Weldon Johnson's anthem "Lift Every Voice and Sing."

|

| Lift Every Voice and Sing, 2004. © Gwendolyn A. Magee. Pieced, quilted, stitched, and appliquéd fabrics, with cording. 41.5"x53". Courtesy of Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Photography: Dave Dawson Photography. |

Introduction

The art flows through me, but does not belong to me alone. It speaks for those who have no voices, whose voices have been ignored, whose voices have been silenced. It relates history and circumstances that must not be forgotten.

—Gwendolyn Ann Magee, ArtistRarely does an individual who has experienced oppression and prejudice find the means of expressing her experience with such masterful skill, in such an appropriate medium, and with such an embracing, uplifting tone.1Bradley, Betsy. "Acknowledgments," in Journey of the Spirit: The Art of Gwendolyn A. Magee, ed. René P. Barilleaux (Jackson, MS: Mississippi Museum of Art, 2004), 3.

—Betsy Bradley, Director, Mississippi Museum of Art

|

| Lift Every Voice and Sing, 1900. Poem by James Weldon Johnson. Music by John Rosamond Johnson. Courtesy of Emory University Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library. |

An extraordinary artist working in fiber, Gwendolyn Ann Jones Magee (1943–2011) produced powerful abstract and narrative works in the medium of quilts. Magee's art, which she came to in midlife, was informed by her childhood in a creative home, her education in the social sciences, participation in the civil rights movement, careers in social work and business, and her experiences as a wife, mother, and grandmother.

A native of High Point, North Carolina, Magee lived most of her adult life in Mississippi. Educated in the public schools of High Point, she graduated from the Woman's College of the University of North Carolina (WCUNC), now the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNCG). This essay, exhibition, and accompanying programming sponsored by the art department of UNCG brings Magee home and helps to raise awareness of her work. In the same spirit of homecoming, the High Point Museum will exhibit selections of Magee's work following the Greensboro exhibition, December 5, 2014–February 21, 2015.

Lift Every Voice and Sing: The Quilts of Gwendolyn Ann Magee features twelve works based on James Weldon Johnson's transformative lyrics, set to music by his brother John Rosamond Johnson, and often referred to as "The Negro National Anthem." The quilt exhibition and this essay feature the twelve pieces as a cohesive body of work in narrative sequence. The exhibition also includes selected works that emphasize Magee's development through the expression of her social concerns and the evolution of her technical skills.

Fascinated with Color

|

| Gwen Magee, 1947. Courtesy of Estate of Gwendolyn A. Magee. |

Magee's childhood and early adult years in the Triad area of North Carolina contributed to the passionate voice she brought to her art. Edith Mayfield Wiggins, a childhood and college friend, remembers young Gwen Jones spinning endless stories and imaginative flights of fancy.2Edith Mayfield Wiggins, telephone conversation with author, July 10, 2014. Hers was a childhood surrounded by art publications and crafts in various media, and included museum trips to New York with her adoptive mother, schoolteacher Annie Lee Jones.3Roland Freeman, "Journey of the Spirit: The Art of Gwendolyn A. Magee," in Barilleaux, Journey of the Spirit. Fascinated with color, Magee recalled trying to dig into paper with crayons to achieve the depths and intensities that could match the pure hues in her mind's eye.4Gwendolyn A. Magee, oral history interview with Larry Morrisey, March 29, 2007. Courtesy of SouthArts. The power of color became a signature of her mature work.

Another influence throughout Magee's childhood and youth that affected her later work was the pervasive presence of "Lift Every Voice and Sing":

I well remember singing it at the beginning of almost every elementary and high school assembly program and at community activities. . . . It speaks to our heritage of slavery and oppression, as well as of our hope for equality, freedom, and justice.5Eleanor Dugan, "The Power of a Series: Gwen Magee Finds Inspiration in an Anthem," Quilting Quarterly, Journal of the National Quilting Association 30, no. 3 (Fall 2001).

I grew up with this song. It's been a major part of my life. All the way through school, we would sing it in assemblies, and sometimes daily in some of my classes. I can remember from about the age of four going with my mother to community programs or events and hearing it. For me, it's a powerfully emotional song, because it deals with pride, cultural heritage, and a clear recognition of all the difficulties African Americans have faced over the centuries.6Magee quoted in Freeman, "Journey of the Spirit."

In the fall of 1959, Gwen Jones, as a new graduate from William Penn High School in High Point, entered the Woman's College of the University of North Carolina in nearby Greensboro. Three years earlier JoAnne Smart and Betty Ann Davis had broken the color barrier at the all-white women's school. Although there were not violent protests or grandstanding in the schoolhouse door, the transition was not easy. Alice Joyner Irby, the newly appointed director of admissions, recalls touring the state, "searching for other black women who could succeed at WC. The women needed to be tough, smart, and ambitious to withstand the volatile culture they'd potentially face."7Sarah Perry, "A Place of Distinction: Woman's College in Greensboro," Our State: North Carolina, January 2014, http://www.ourstate.com/womans-college-greensboro/. By the time Jones and her four freshman cohorts arrived on campus they found themselves segregated in one section of one dormitory, and the target of discrimination, both subtle and not.8Magee, on her college years, quoted in Freeman, "Journey of the Spirit." The school was desegregated but not fully integrated.

|

| Gwendolyn Ann Jones, 1963. Photo from Woman's College of the University of North Carolina yearbook, Pine Needles. |

During Gwen Jones's college years, 1959–1963, Greensboro was a center of civil rights activities, best known as the site of the Woolworth's sit-ins initiated by four North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University (A&T) students9Known as the Greensboro Four, the A&T freshmen were Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair, Jr. (later known as Jibreel Khazan), and David Richmond. in February 1960. Advised by WCUNC administrators not to participate in the local demonstrations, between 1962–1964 Jones along with other students, black and white, targeted businesses adjacent to the campus and eventually prevailed in integrating the neighborhood movie theater and restaurants. Full integration did not occur until after she had graduated.

In a 1990 interview, Dr. M. Elaine Burgess, one of Magee's most influential professors in her major, sociology, recalled the action:

The kids were the ones that were doing it. They were brave. And they were so disciplined because they were frightened 'cause the Ku Klux Klan would come rolling up. They were never in danger, but they didn't know. You know, those early days—those young southern girls. That was a pretty big step. . . . I felt they did a nice job. And they organized it.10Oral history interview with M. Elaine Burgess, 1990, Martha Blakeney Hodges Special Collections and University Archives, University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

After her 1963 graduation with a BA in sociology, Jones continued graduate study in social science at Kent State and Washington universities, working as an assistant with various research projects. She did not pursue a graduate degree, but took a fieldwork assignment. All of these experiences helped sharpen the consciousness that would inform her art.

In 1969 Gwen married Dr. D. E. Magee, an ophthalmologist she met during fieldwork in Mound Bayou, Mississippi. After Dr. Magee completed his residency in Philadelphia, the couple moved to Jackson, Mississippi, where they established careers and raised their two daughters, Kamili and Aliya. Although she had continued during the passing years to practice a variety of craft media while employed with Xerox, Merrill Lynch, and other corporate and minority placement programs, Magee decided in 1989 that she should learn to quilt in order to create reminders of home for her college-bound daughters. She discovered her artistic voice in the fiber arts, swiftly mastering quilting and surface design techniques through which she powerfully expressed herself and engaged an audience.

|  | |

| Gwen Magee at work on her abstract design Bolero. Photography by J.D. Schwalm and The Clarion-Ledger, 2001. | Gwen Magee at work with her daughter Kamili Magee Hemphill and Grandson Ellington Hemphill. Photo courtesy of Roland L. Freeman, 2014. |

Gwen Magee's first works in traditional quilting soon moved into abstract designs, and then references to African culture through the use of textile and design traditions. She reveled in and fine-tuned her fascination with the intensity and interplay of color. As she developed her skills, techniques, composition, and color management, she was also laying the groundwork for a transition in subject matter. As she studied quilting periodicals she discovered the narrative work of other African American quilters, which inspired a growing dissatisfaction with her own work as lacking in cultural relevance and significance. The artist challenged herself to create work satisfying to an audience of one, herself, responding to her need to deal with her own history and heritage. Her vision expanded to include her concern with social justice and African American heritage in the creation of extraordinary textile narratives.11Magee and Morrisey.

Lift Every Voice and Sing: The Quilts of Gwendolyn Ann Magee

The exhibition, Lift Every Voice and Sing: The Quilts of Gwendolyn Ann Magee, includes examples of the artist's work created concurrently with the title series (2001–2011) that illustrate the strengths of her approach. Although Magee's first ventures into quilting had expressed affirmative emotions toward domestic life, she understood the toughness of the subjects she chose to address as her narrative direction developed, and did not flinch from the use of powerful imagery. "I am fully aware," she blogged in 2009, "that the dissonance is palpable between this medium through which my art finds expression and the subject matter that it articulates. I know that the quilt form usually is associated with feelings of warmth, comfort, serenity and security and that my subject matter often is harsh, intense, somber and frequently brutal. However, viewers of the art frequently convey to me that they find the work to be compelling, evocative, meaningful and riveting."12Gwendolyn A. Magee, "Gwendolyn Magee in Her Own Words", Subversive Stitchers: Women Armed with Needles, February 6, 2009, http://subversivestitch.blogspot.com/2009/02/gwendolyn-magee-in-her-own-words.html.

"Shocking Quilts: We Show You the Controversial Patchwork" read the cover of a 2009 Quilter's Home magazine that included some of Magee's narrative works. The Washington Post commented on the resulting kerfuffle over censorship after a few traditional quilt shops, including the Jo-Ann Fabrics chain, refused to carry the issue:

"Some of the images are disturbing—and moving—like quilter Gwen Magee's Southern Heritage/Southern Shame, which depicts five lynching victims hanging in front of a Confederate flag. . . . Magee says that the contrast between her soft fabrics and her harsh social messages is exactly what makes her work effective. She did see a letter from one guy protesting her quilts, asking, 'Who would want to cuddle under such a thing?' 'He had no concept that this wasn't that kind of quilt,' Magee says."13Monica Hesse, "Quilting Magazine Exposes Craft's Risque Underside," Washington Post, March 5, 2009, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/03/04/AR2009030403994.html.

Southern Heritage/Southern Shame

This was my response to the failure of a referendum to remove the Confederate battle emblem from the Mississippi state flag.

—Gwen Magee

|

| Southern Heritage/Southern Shame, 2001. © Gwendolyn A. Magee. Pieced, quilted, and appliquéd fabrics, with cording. 22.5"x32.5". Collection of Michigan State University Museum, East Lansing, Michigan. Purchased with funding from the MSU Office of Research and Graduate Studies and the MSU Foundation. Photography © 2014 Roland L. Freeman. |

This multilayered quilt, with its narrative elements and use of transparencies to create layers of meaning, is now in the collection of the Michigan State University Museum. The Confederate battle flag is overlaid with silhouettes of lynched bodies, but the left side of the work is deceiving—at first glance viewers may try to blink away a fog or a smudge. But suddenly, through Magee's skilled use of materials, a figure emerges and the shadowy, hooded figure leaps into view.

Five Years Hard Labor

In blisteringly hot sun, chain gang prisoners break rocks under the watchful eye of an armed guard and his dog.

—Gwen Magee

The Mississippi Museum of Art commissioned Five Years Hard Labor for The Mississippi Story, a selection of more than three hundred objects from its permanent collection of work by artists from around the state. Magee's narrative features one notorious element of Mississippi history, a chain gang, in a highly textured work.

This work combines techniques and design elements characteristic of Magee's style: diversely textured fabrics, intense color to enhance the mood, and heavy threadwork. The threadwork (often created with free motion machine embroidery) builds up textures in layers and helps unify the surfaces across a body of work, just as a painter's brushwork can become a style signature.

As in Five Years Hard Labor, human figures in Magee's work often appear as featureless profiles, reminiscent of Romare Bearden's pictorial narratives. The postures and apparel of the chain gang figures identify their status.

Magee's use of spiral elements lends universality to her compositions. The angry sun, an agitated disc in the chain gang quilt, combines shape, motion, and intense color to emphasize the scene's heat. A spiraling background texture echoes the sun.

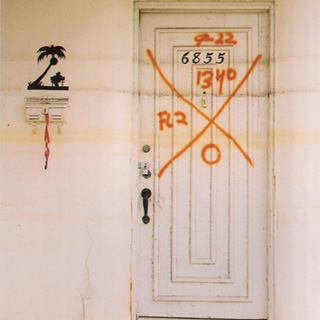

Requiem

This is a lament for a vibrant city that will never again be the same with the devastation wreaked by Hurricane Katrina compounded by the indifference and ineptitude of our government.

—Gwen Magee

Requiem represents another example of Magee's reactions to current events, and was the beginning of a planned series about Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath. Magee completed only two pieces in this series. Family ties in New Orleans and keen attachments to the city, coupled with growing horror at government failures to deal with an overwhelming natural and manmade disaster drove the creation of this work. Requiem combines references to musical culture, a street corner significant to Magee's family, and the encroaching floodwaters where streams of music pouring from the trumpet meet and blend with streams of water flowing through broken levees.

Multiple details—the variety of specialty and hand-dyed fabrics mimicking decorative ironwork, window glass, the musician's alligator shoes, and the luminosity of a street lamp—enhance the strengths of the Katrina narrative told in one vignette. Heavy thread work suggests layers of architectural and cultural history on a typical street corner. The featureless figure of a musician propped against a street lamp stands in as a cultural icon. The spiral elements make their appearance, but in this work they are distorted and their perpetual motion diverted. On first glance, an arched doorway appears to frame rich shadows and coloring achieved with intense thread work that, when examined, emerge from the background as a montage of abstract images—a spiraling hurricane, rampaging water, a levee break—framed by an architectural feature.

Expendable Cargo

Slavers continued to operate even after importation of slaves became illegal. However, if the patrol ships were bearing down on them on the high seas, the illegal cargo was unceremoniously dumped overboard to drown - if no slaves were found on board there would be no imprisonment or fines.

—Gwen Magee

|  |

| Expendable Cargo, 2010. © Gwendolyn A. Magee. Pieced, quilted, and appliquéd cotton, with cording. 82"x18". Collection of Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson. Purchase, with funds from McCravey Fund, 2013.014. Photograph © 2014 Gil Ford Photography. Detail photograph by Dave Dawson Photography. | |

On completion of Lift Every Voice, Magee began another African American history series. Expendable Cargo is representative of this body of work depicting harrowing facets of enslavement—here, the jettisoning of human cargo to rid a pursued ship of incriminating bodies. The shape of the quilt emphasizes the descending human figures, weighted and dragged downward by restraints, silhouettes shackled together, sinking through the depths of blue waves.

Expendable Cargo, part of Slavery Series, in the collection of the Mississippi Museum of Art is composed of quilts that are generally smaller in format and treated with less visual complexity than other Magee works. Again, Slavery Series' figures are featureless. Each represents a story of slavery told and retold. The surfaces are not as intensely worked, but the graphic qualities are inescapably direct. Some of the work moves toward sculptural adaptations that extend from the surface. Intensely experienced by the artist and viewers, images and narratives pour from Magee's Slavery Series, as if she seems compelled to create them as quickly as possible.

Deep Into the Woods

|

| Deep into the Woods, 2011. © Gwendolyn A. Magee. Pieced, quilted, stitched, and appliquéd fabrics. 16"x11.75"(closed), 16"x11.75"x23" (open). Collection of the Gwendolyn Ann Magee Estate, D. E. Magee, administrator. |

Deep Into the Woods, one of Magee's later works, offers a purely sculptural means of telling a story, and represents an increasing transition from two-dimensional wall work into representations with more depth. This aptly named category of handmade objects is called a tunnel book. Using this multi-dimensional format, Magee layered in story elements, capturing a chilling moment in the deep woods. The stylized spiral foliage frames a hooded figure peering out from the depths, backed up by flames, an empty noose, and the Confederate battle flag. While Magee created many pieces that incorporated layers—using transluscent and sculpted fabrics, along with machine stitching—she found that the tunnel book format enabled her to express with actual (as opposed to illusive) depth the layers of meaning and imagery characteristic of her work.

|

| Deep Into the Woods, alternate view. Photograph by Dave Dawson Photography. |

Verse One: Lift Every Voice

The title series of this exhibition draws its inspiration from the majestic words and music of "Lift Every Voice and Sing." The song's lyrics are a major legacy from James Weldon Johnson, and a crucial contribution to the twentieth-century struggle for civil rights. Johnson's achievements in many fields were acknowledged in the 2007 creation of Emory University's James Weldon Johnson Institute, but "his place in African American history and culture would be secure if he had composed only in 1900 with J. Rosamond Johnson 'Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing,' a hymn officially adopted by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and widely sung by African Americans as the Negro National Anthem."14"About James Weldon Johnson," The James Weldon Johnson Institute for the Study of Race and Difference, http://jamesweldonjohnson.emory.edu/home/about/index.html.

Julian Bond and Sondra Kathryn Wilson articulated the power of "Lift Every Voice" in the introduction to their book of tributes on the 100th anniversary of the song's creation:15Julian Bond and Sondra Kathryn Wilson, eds., Lift Every Voice And Sing: A Celebration of the Negro National Anthem: 100 Years, 100 Voices (New York: Random House, 2000). "It is wondrous and hardly explicable to many," wrote Bond and Wilson, "how James Weldon Johnson could have written such spiritually enriching lyrics in 1900 . . . 'Lift Every Voice and Sing' is fittingly provocative. Yet its message, ingeniously crafted, does not fuel the fires of racial hatred."16Ibid.

Magee's Lift Every Voice series translates the song's verbal images into powerful visuality. Images from words embedded in life experience were shared through well-developed skills that conveyed both the history and the passion of shared time and participation. " I had mental pictures inspired by the words," recalled Magee's longtime friend Edith Wiggins, "and when I saw Gwen's series my reaction was, 'Yes—that's exactly what I was thinking.' The series helps to validate and underscore what you've always felt and visualized."17Wiggins and Moye.

In a 2007 interview, Magee summed up her wishes that her legacy be "a body of work that not only is meaningful but is compelling, through its use of color, design, and/or subject matter—so that the viewer is not only engaged but is drawn into the work and, hopefully, back to it repeatedly."18Magee and Morrisey.

Lift every voice and sing

Till earth and heaven ring

Ring with the harmonies of Liberty;

Let our rejoicing rise

High as the listening skies,

Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.

Lift Every Voice and Sing

The full color spectrum not only of African-Americans, but of all peoples of the world is depicted. All should be able to find themselves represented.

—Gwen Magee

In her title piece to the series, Magee uses a spectrum of skin colors to introduce her wish to cross boundaries that separate humankind. The featureless profiles lift their voices, eyes, and heads.

The placement of the globe and text in a night sky, enhanced with sparkling stars and a texture of meander quilting suggesting swirling galaxies, connects this title piece to the "the blue marble"19A description of the term applied to the planet Earth, as described by the crew of Apollo 17: http://life.time.com/history/blue-marble-apollo-17-photo-of-earth-from-space/#1. Meander quilting is a technique in which non-overlapping quilting stitches meander across a quilt in a fluid, seemingly random fashion. perspective of earth, as viewed from space. The rainbow of faces lifted in hope, and the implied voices lifted in song convey Magee's hope for a universe that will "ring with the harmonies of liberty."

Full of the Faith

Three women kneel in the shadow of the cross to indicate their submission to the will of a higher power. This piece conveys the important role played by religion during slavery and reconstruction.

—Gwen Magee

|

| Full of the Faith, 2004. © Gwendolyn A. Magee. Pieced, quilted, stitched, and appliquéd fabrics, with cording. 42.5"x37". Collection of the Gwendolyn Ann Magee Estate, D. E. Magee, administrator. Photograph by Dave Dawson Photography. |

|

| Full of the Faith, 2004. Detail. Photograph by Dave Dawson Photography. |

Multilayered in technique and meaning, this work depicts the centrality of faith in African American culture. Identified by their profiles and postures as a young woman, a mature woman, and an older woman, the three kneeling figures are iconic for their generational span and for their strength. These three figures, although flat fabrics, are visually contoured with the use of linear work that is an internal echo of the outlines shapes. The cross, with its African-patterned textiles, casts a protective shadow on the trio.

The cross rises from a richly embroidered billow of threadwork in deep and varied reds with gold overlays, a tour de force of surface work. The sheer beauty of this background belies reference to the smoldering and smoking remains of another form of burning cross all too familiar to African American history—another lesson of "the dark past."

Full of the Hope

Youth and education have long been very powerful symbols of hope for African-Americans with education viewed as our road map for making it into 'the promised land'.

—Gwen Magee

|

| Full of the Hope, 2002. © Gwendolyn A. Magee. Pieced, quilted, stitched, and appliquéd fabrics, with cording. 42"x40". Collection of the Gwendolyn Ann Magee Estate, D. E. Magee, administrator. Photograph by Dave Dawson Photography. |

|

| Full of the Hope, 2002. Detail. Photograph by Dave Dawson Photography. |

Full of the Hope invokes the potential of education. With its open, serious faces and uplifted eyes, this is one of only three pieces in the exhibition that do not portray figures in featureless profile. The young man and woman in cap and gown and with diplomas in hand, stand in the light of golden rays. Magee believed fervently in the power of education, and spoke frequently to school groups as a part of her artistic mission.The graduation gowns are adorned with stoles emblematic of racial pride.

Our New Day Begun

A blazing sun symbolizes hope.

—Gwen Magee

The climax of the first stanza of Johnson's anthem is the title phrase for Magee's Our New Day Begun. A geometrically complex sun shines forth from a hand-dyed background, its luminosity enhanced with intricate lines of shading from meander lines of variegated thread work. The rising sun of this text is not the angry, spiraling sun of other works, but a glowing symbol of purpose and belief in the future.

Verse Two: Stony the Road We Trod

A slave coffle gives testimony to the miles and miles that men, women, and children were forced to trudge while shackled and chained.

—Gwen Magee

Moving into a second verse, Johnson's anthem turns toward history, as does Magee's imagery. She does not avoid the terrors of slavery as she translates words to visuals.

A variegated deep red background and profiled black feet suggest the bloody treks of shackled slaves traveling to unknown destinations, before and after the Middle Passage. The horizontal format of the quilt emphasizes the distance of these treks over perilous terrain. Interior contour lines emphasize the three-dimensiality of the trudging feet.

Bitter the Chastening Rod

The image of a chained woman being cruelly whipped even though her womb is heavy with child graphically illustrates the dehumanization of slaves.

—Gwen Magee

|

| Bitter the Chastening Rod, 2000. © Gwendolyn A. Magee. Pieced, quilted, stitched, and appliquéd fabrics, with cording. 43.75"x39". Collection of the Gwendolyn Ann Magee Estate, D. E. Magee, administrator. Photography © 2014 Dave Dawson Photography. |

As she is whipped, a chained, pregnant, enslaved woman raises her voice in naked anguish. The stark black and white palette underscores the bitter verse as a featureless profiled figure represents numberless cruelties, violations, and abuses. Again, the interior linework on the silhouette emphasizes the contours of the writhing body.

| |

| Bitter the Chastening Rod, 2000. Detail. Photograph by Dave Dawson Photography. |

When Hope Unborn Had Died

A couple has bought a hog and a toddler at auction. Its mother, screaming in anguish, runs desperately out of the cotton field.

—Gwen Magee

The flat plane of two-dimensional artwork cannot contain the emotions of When Hope Unborn Had Died. An anguished mother, weighed down by a heavy cotton sack, screams across the unfolding scene. A parasol obscures the couple that has purchased her child, as a high stepping horse moves their carriage, cart, and cargo diagonally toward the edge of the frame, soon to disappear.

The action originates in the viewers' space as the three-dimensional sack of cotton drags out of the picture plane and anchors the mother in a powerless dimension. Viewers who approach this work are drawn into the narrative and to the figure whose futile scream floats above the carriage. Her featureless profile with its screaming mouth echoes the cries of countless mothers during generations of American slavery.

The use of fabrics as identifiers is particularly strong here. The slave mother wears rough cloth resembling the homespun of field work; the cotton sack is of burlap. The shielding parasol is of shiny, luxury cloth; the dappled horse is an irregularly dyed fabric; and the sun is a shiny, intense yellow. The stark, stylized tree with its unnatural spiral foliage echoes the angry sun.

Yet with a steady beat,

Have not our weary feet

Come to the place for which our fathers sighed?

We have come over a way that with tears has been watered

We Have Come Over a Way That with Tears Has Been Watered

A slave ship plunges through ocean waters. Blazing in the sky the sun depicts the turmoil of the voyage. Slave trade routes are depicted by the quilting lines connecting Africa and the United States.

—Gwen Magee

A slave ship in full sail splitting the waters of the Atlantic evokes the Middle Passage in Over a Way that with Tears Has Been Watered. The atmosphere echoes the turmoil of the human cargo; a spinning sun of judgment emits jagged rays, filling the dark sky as turbulent waters crash the ship's hull.

The white sails billow and propel the ship through deep waters. The sails and the hold of the ship, with the telltale name of Amistad, are surrounded by a nest of tangled white threadwork, suggesting the rising miasma of misery.

Almost obscured in the chaos is the relentless path of map lines indicating slave voyages connecting Africa in the upper right corner to the Americas in the lower left.

Blood of the Slaughtered I and II

"Treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered . . ." The words haunted me for months—reverberating in my head over and over again; nine little words embodying a multiplicity of possible interpretations. But one meaning in particular resonated mercilessly. This single line . . . gripped me at the deepest core of my being and left me with no refuge.

—Gwen Magee

|

| The Blood of the Slaughtered I, 2001. © Gwendolyn A. Magee. Pieced, quilted, stitched, and appliquéd fabrics, with cording. 70"x85.5". Collection of the Gwendolyn Ann Magee Estate, D. E. Magee, administrator. Photography © 2014 Dave Dawson Photography. |

By their title The Blood of the Slaughtered I and II warns viewers that this work is difficult to imagine and to comprehend. The listing of names of documented lynching victims is Magee's memorial—a textile roll call for viewers to read and ponder.

The names of the lynched, recorded by state, and localized within each state, brings the horrific history home. This is a memorial piece, a Vietnam Wall in cloth. With the spiraling tree in translucent overlay, fading body, and stark black and white palette, every element of this piece is stark and compelling.

|  |

| Blood of the Slaughtered I, 2001. Detail above, below. Photograph by Dave Dawson Photography. | |

| |

| The Blood of the Slaughtered II, 2001. © Gwendolyn A. Magee, Pieced, quilted, stitched, and appliquéd fabrics, with cording. 70"x18". Collection of the Gwendolyn Ann Magee Estate, D. E. Magee. |

Out from the gloomy past,

Till now we stand at last

Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast

Verse Three: God of Our Weary Years

God of our weary years,

God of our silent tears,

As African Americans, just as we have so much hope for our youth to 'lead the way' and to 'fulfill the dream,' we also have to daily face the reality that for countless reasons many of our youth, particularly if they are male and teenagers,somehow wind up being touched by the criminal justice system. This piece speaks to that issue.

—Gwen Magee

The face above the prison orange peering between bars—the same face as the eager graduate in Full of the Hope—stands in for a generation of black youth caught in persisting structural conditions of poverty and lack of education who may become a part of modern-day mass incarceration.

God of Our Silent Tears I

An execution scene addressing the disproportionate percentage of African Americans given the death penalty and executed. It does not address the question of guilt or innocence, but questions whether or not our system of justiceIs truly equal for all.

—Gwen Magee

God of Our Silent Tears I takes viewers into the execution chamber, where the life force of a condemned man fades, marked by the receding image of his body as an overhead hand throws the switch to the electric chair. Magee has chosen to give this figure an African American face and not portray him as a featureless profile. The tableau reminds viewers that capital punishment in America imposes unequal racial judgment in society's name.

God of Our Silent Tears II

This companion piece looks at execution from another perspective—that of the family being left behind, for they, too, will suffer. Each of the three newspapers shown takes a different position—one is against capital punishment and also questions the politics of the trail and whether or not this man was railroaded for political reasons. Another paper takes the position that the evidence clearly proved his guilt and that he therefore should be executed.The third takes a middle of the road point of view.

—Gwen Magee

As the family of a condemned man waits, and the clock nears the appointed hour of midnight, God of Our Silent Tears II portrays the other side of the execution scene, that of the "family being left behind."

Thou Who Has Brought Us

Thou who has brought us thus far on the way;

Thou who has by Thy might

Led us into the light,

Keep us forever in the path, we pray.

Lest our feet stray from the places, our God, where we met Thee,

Lest, our hearts drunk with the wine of the world, we forget Thee;

Shadowed beneath Thy hand,

May we forever stand.

True to our God,

True to our native land.

Gwen Magee's series doesn't interpret the final lines of Lift Every Voice, but could be reprised by the hope expressed in Our New Day Begun. The spirit of Magee's work—informed by history but not overwhelmed by sorrow—complements the anthem that inspired her throughout her life.

Infinity

|

| Infinity, 1995. © Gwendolyn A. Magee. Pieced, quilted, and stitched, fabrics. 105.5"x90". Collection D. E. Magee. Photography © 2014 Dave Dawson Photography. |

Infinity, the last quilt in the narrative sequence of Lift Every Voice and Sing: The Quilts of Gwendolyn Ann Magee, voices the joy Gwen Magee knew in her life, the love she experienced for her family and friends, and the legacy of her work. Early in the chronology of her work in fiber, Magee created Infinity as a Christmas gift for her husband, D. E. Magee. Just beginning to flex her creative muscles, she worked from a traditional quilt pattern that she altered to celebrate Dr. Magee's serious hobby of astronomy and his profession as an ophthalmologist.

|

| Infinity, 1995. Detail. Photograph by Dave Dawson Photography. |

Infinity glows with intensity of color and precise geometry, successfully moving light across the surface while creating illusions of dimension through the manipulation of color and form. Dr. Magee's insistence that this was a work of art for the wall and not a bed covering marked a turning point from which Gwen Magee recognized and identified herself as an artist.

Curator René Barilleaux, who worked with Magee on her exhibition, Journey of the Spirit, at the Mississippi Museum of Art, sums up her life in the arts: "Gwen Magee was a rare combination of artist, advocate, and gentle spirit. In her life and in her art, she made monumental statements on those things about which she cared deeply."20René Barilleaux, e-mail communication with author, April 5, 2013.

|

| Gwendolyn Ann Magee, 1943–2011. Photograph by Barbara Gauntt. © Barbara Gauntt/Clarion-Ledger. |

About the Artist

Gwendolyn Ann Magee has work in the permanent collections of the Mississippi Museum of Art, the Museum of Mississippi History (Department of Archives and History), the Michigan State University Museum, and the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian Museum of American Art. Magee's work also has been exhibited in the Museum of Arts and Design, the Atlanta History Museum, the National Art Gallery of the Republic of Namibia, the Val d'Argent Expo in Alsace, France, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and at numerous other national and international galleries. Among other honors she was recognized by the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters as Visual Artist of the Year in 2003 and she was a 2007 Ford Fellow through United States Artists.21Gwendolyn A. Magee, "Exhibitions/Resume," http://gwenmagee.com/resume.html.

About the Author

Dorothy Moye is a Decatur, Georgia, art consultant and a college classmate of Gwen Jones Magee (WCUNC '63). She is Visiting Curator for the Gatewood Gallery at UNC-Greensboro, for Lift Every Voice and Sing: The Quilts of Gwendolyn Ann Magee, September 11–November 8, 2014. Other curatorial projects in 2014-15 include Flight Patterns: A Fiber Art Exhibition, at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport through April 2015 and at the Welch Gallery, Georgia State University May 14–July 31, 2015; and semiannual exhibitions through the Decatur Arts Alliance.

Moye participates in multifaceted projects in the arts, and holds membership in numerous arts organizations, both local and national. She graduated from UNC–Greensboro and North Carolina State University in Raleigh with degrees in sociology.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank those who have worked tirelessly to bring the work of Gwendolyn Ann Jones Magee to a wider audience.

- The Magee Family: Dr. D. E. Magee, MD; Kamili Magee Hemphill; and Dr. Aliya Magee, DVM for sharing their legacy with the world.

- Dr. Lawrence Jenkens and the staff of the Art Department at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro for belief in this project and the opportunity to curate an exhibition of the work of my friend Gwen Magee.

- Dr. Allen Tullos, Jesse P. Karlsberg, Meredith Doster, and the outstanding editors and staff of Southern Spaces for the opportunity to give ongoing digital life to the Gwen Magee Project. Thanks in particular to Emma Lirette and Clinton Fluker for their work laying out this piece.

- Carol Furey Matney and the other members of the Magee Project Committee for support and assistance and making this project possible: Bill Baites, Linda Arnold Carlisle, JoAnne Smart Drane, Day Heusner McLaughlin, Maggie Triplette, Charlotte Vestal Wainwright, and Edith Mayfield Wiggins.

- The director and staff of the Mississippi Museum of Art for assistance in the logistics of the project, as well as for the loan of three important works.

- The Mississippi Department of Archives and History and the Michigan State University Museum for their generous loans.

- South Arts for access to an important oral history from their archives.

- Family and friends for valuable support and assistance in every aspect of this project.

- The African American graduates of the Woman's College of the University of North Carolina (1960–1963) who pioneered the way to the most diverse campus in the state's university system, the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Recommended Resources

Text

Barilleaux, René P., ed. Journey of the Spirit: The Art of Gwendolyn A. Magee. Jackson, MS: Mississippi Museum of Art, 2004.

Bond, Julian and Sondra Kathryn Wilson, ed. Lift Every Voice And Sing: A Celebration of the Negro National Anthem • 100 Years, 100 Voices. New York: Random House, 2000.

Dugan, Eleanor. "The Power of a Series: Gwen Magee Finds Inspiration in an Anthem." Quilting Quarterly, Journal of the National Quilting Association 30, no. 3 (Fall 2001): 8–10.

Herring, Lori. "Covering the Issues: Quilter Comments on Life through Craft." Jackson Clarion-Ledger, June 3, 2001.

Hesse, Monica. "Quilting Magazine Exposes Craft's Risque Underside." The Washington Post, March 5, 2009. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/03/04/AR2009030403994.html.

Hubbell, Leesa. "Gwendolyn Magee Receives Mississippi 2011 Governor's Award." Surface Design Association NewsBlog, November 10, 2010. http://www.surfacedesign.org/newsblog/2-sda-members-win-high-profile-awards.

Kane, Dawn. "Gwen Magee's Quilts Come Home to UNCG." Greensboro News and Record, September 4, 2014. http://www.news-record.com/go_triad/gwen-magee-s-quilts-come-home-to-uncg/article_f8c16dea-3437-11e4-9e82-0017a43b2370.html.

Lucas, Sherry. "Threads of Anguish, Hope Emerge from Quilts: 'Journey of the Spirit.'" Jackson Clarion-Ledger, November 17, 2004.

Magee, Gwendolyn A. "Gwendolyn Magee in Her Own Words." In Subversive Stitchers: Women Armed with Needles, February 6, 2009. http://subversivestitch.blogspot.com/2009/02/gwendolyn-magee-in-her-own-words.html.

Perry, Sarah. "A Place of Distinction: Woman's College in Greensboro." Our State: North Carolina, January 2014. http://www.ourstate.com/womans-college-greensboro/.

"Remembering Gwendolyn A. Magee: an extraordinary artist/quilter." Hush: Hearing Ushers Salvation's Healing, May 2016. http://www.hush-be-still.com/arts-%E2%80%A2-literature.html#sts=Remembering Gwendolyn A. Magee:.

Web

Magee, Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn Magee: Textile Artist. http://www.gwenmagee.com.

———. Textile Arts Resource Guide. http://creativityjourney.blogspot.com

"Quilts at the V&A, [an Interview with Gwendolyn A. Magee]." BBC, last updated March 17, 2010. http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/arts/2010/03/100317_strand_quilts.shtml.

"The Slave Series: Quilts by Gwendolyn A. Magee." Mississippi Museum of Art. http://www.msmuseumart.org/index.php/exhibitions/exhibition/the-slave-series-quilts-by-gwendolyn-a.-magee.

Studio Art Quilt Associates. http://www.saqa.com/.

Women of Color Quilters' Network. http://www.wcqn.org/.

Audio/Video

Charles, Ray. "Lift Every Voice and Sing." YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QU8921j20e8.

Morehouse College Glee Club. "Lift Every Voice and Sing." YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JjEO1XEo1ws.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Bradley, Betsy. "Acknowledgments," in Journey of the Spirit: The Art of Gwendolyn A. Magee, ed. René P. Barilleaux (Jackson, MS: Mississippi Museum of Art, 2004), 3. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Edith Mayfield Wiggins, telephone conversation with author, July 10, 2014. |

| 3. | Roland Freeman, "Journey of the Spirit: The Art of Gwendolyn A. Magee," in Barilleaux, Journey of the Spirit. |

| 4. | Gwendolyn A. Magee, oral history interview with Larry Morrisey, March 29, 2007. Courtesy of SouthArts. |

| 5. | Eleanor Dugan, "The Power of a Series: Gwen Magee Finds Inspiration in an Anthem," Quilting Quarterly, Journal of the National Quilting Association 30, no. 3 (Fall 2001). |

| 6. | Magee quoted in Freeman, "Journey of the Spirit." |

| 7. | Sarah Perry, "A Place of Distinction: Woman's College in Greensboro," Our State: North Carolina, January 2014, http://www.ourstate.com/womans-college-greensboro/. |

| 8. | Magee, on her college years, quoted in Freeman, "Journey of the Spirit." |

| 9. | Known as the Greensboro Four, the A&T freshmen were Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair, Jr. (later known as Jibreel Khazan), and David Richmond. |

| 10. | Oral history interview with M. Elaine Burgess, 1990, Martha Blakeney Hodges Special Collections and University Archives, University of North Carolina at Greensboro. |

| 11. | Magee and Morrisey. |

| 12. | Gwendolyn A. Magee, "Gwendolyn Magee in Her Own Words", Subversive Stitchers: Women Armed with Needles, February 6, 2009, http://subversivestitch.blogspot.com/2009/02/gwendolyn-magee-in-her-own-words.html. |

| 13. | Monica Hesse, "Quilting Magazine Exposes Craft's Risque Underside," Washington Post, March 5, 2009, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/03/04/AR2009030403994.html. |

| 14. | "About James Weldon Johnson," The James Weldon Johnson Institute for the Study of Race and Difference, http://jamesweldonjohnson.emory.edu/home/about/index.html. |

| 15. | Julian Bond and Sondra Kathryn Wilson, eds., Lift Every Voice And Sing: A Celebration of the Negro National Anthem: 100 Years, 100 Voices (New York: Random House, 2000). |

| 16. | Ibid. |

| 17. | Wiggins and Moye. |

| 18. | Magee and Morrisey. |

| 19. | A description of the term applied to the planet Earth, as described by the crew of Apollo 17: http://life.time.com/history/blue-marble-apollo-17-photo-of-earth-from-space/#1. Meander quilting is a technique in which non-overlapping quilting stitches meander across a quilt in a fluid, seemingly random fashion. |

| 20. | René Barilleaux, e-mail communication with author, April 5, 2013. |

| 21. | Gwendolyn A. Magee, "Exhibitions/Resume," http://gwenmagee.com/resume.html. |