Overview

An Alabama redistricting case before the US Supreme Court will have a monumental impact on the voting rights of African Americans and on the nation's faith in its democratic promise.

Essay

|

| Map of Alabama with percentage of white population. Map based on image courtesy of Social Explorer. |

Seven years ago, as I sat doing research at the historical society of Shelby County, Alabama, a county commissioner arrived, hailing the librarian and me. "Happy Martin Luther Coon Day!" he shouted. Earlier this year, on the last day of February, Shelby County's lawyers appeared before the US Supreme Court to argue that Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 is no longer constitutional. By the end of June, the Court is expected to rule whether the "burdens of preclearance" on our federal system of government outweigh the continuing burden of southern history with regard to race. The decision will have a monumental impact on the voting rights of African Americans and on the nation's faith in its democratic promise.

Since 1965 Section 5 has required the states of Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Virginia as well as scattered counties in North Carolina to seek clearance from the US Justice Department or a DC federal court before implementing a change in voting laws. In 1972, Texas, Arizona, Alaska, and a few local jurisdictions in five other states were added due to more recent voting rights problems.1For more information about covered jurisdictions see "Section 5 Covered Jurisdictions," United States Department of Justice, accessed May 21, 2013, http://www.justice.gov/crt/about/vot/sec_5/covered.php.

Congress enacted Section 5 because state and local officials habitually obstructed the voting rights of black and Hispanic citizens in innumerable ways. Any jurisdiction can remove the need for pre-clearance if it shows it has had a clean record of not denying the voting rights of people of color during the last ten years, and more than one hundred towns and counties across the South and nation have done so.

In 2009, Chief Justice John Roberts set the stage for the Shelby County case when he observed in an opinion: "The historic accomplishments of the Voting Rights Act are undeniable, but the Act now raises serious constitutional concerns . . . Things have changed in the South."2Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District No. One v. Holder, Transcript, No. 08-322, 557 US 193 (2009), 195, 202, http://www2.bloomberglaw.com/public/desktop/document/Northwest_Austin_Mun_Utility_Dist_No_One_v_Holder_129_S_Ct_2504_1. Like opponents to Section 5, Roberts cited increases in black and Hispanic voter registration and in the number of elected officials as evidence of how much the South has changed since 1965.

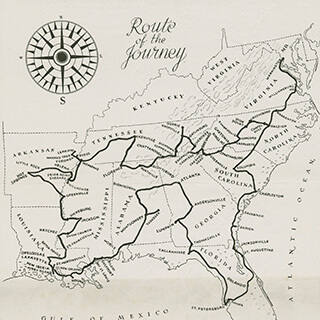

|

| Map of Section 5 covered jurisdictions, 2008. Courtesy of the US Department of Justice. |

In February of this year, during oral arguments before the Supreme Court, Justice Sonia Sotomayor challenged Shelby County's lawyer as soon as he repeated the Chief Justice's claim that it was "unmistakable that the South had changed." The Court's only Hispanic justice pointed out that since 1965 Shelby County's officials and representatives had attempted to enact 240 different discriminatory voting laws that were blocked by Section 5 in a place where African Americans have never comprised more than eleven percent of total population.3Shelby County, Alabama v. Holder, US Supreme Court Oral Arguments, Transcript, No. 1296, February 27, 2013, 3–4, http://www.supremecourt.gov/oral_arguments/argument_transcripts/12-96.pdf. The case before the Supreme Court involves a redistricting plan for one of Shelby County's small towns, Calera, which redrew political boundaries that eliminated the only district in which black voters were able to help elect the candidate of their choice.

Chief Justice Roberts and Associate Justice Antonin Scalia were more interested in discussing race relations in the South than voting rights in Calera. Roberts asked the lawyer for the Justice Department: "Is it the government's submission that the citizens in the South are more racist than citizens in the North?"4Shelby County v. Holder, Oral Arguments, 40–41.

Was Chief Justice Roberts slyly proposing that Section 5 should extend from sea to shining sea? Probably not. Roberts's question sounded more like the political posturing that Alabama's late Governor George Wallace used to make when he was playing politics with black citizens' voting rights.

There is polling data from recent years strongly suggesting that southern whites do continue to have decidedly more negative racial attitudes than whites in other parts of the nation. In a detailed 2005 study, political scientists Nicholas Valentino and David Sears concluded that at the end of the 1960s civil rights campaigns, and in recent years, southern whites "remain more racially conservative than whites elsewhere on every measure of racial attitudes ordinarily used in national surveys."5Nicholas A. Valentino and David O. Sears, "Old Times There Are Not Forgotten: Race and Partisan Realignment in the Contemporary South," American Journal of Political Science 49, no. 3 (July 2005): 685, http://web.posc.jmu.edu/seminar/readings/4a-realignment/race+party%20realignment%20in%20the%20south%20old%20times%20not%20forgotten.pdf. On the 150th anniversary of the Civil War's beginning, a 2011 Pew Center survey found that twenty-two percent of self-identified southern whites react positively when they see the Confederate flag displayed, compared with just four percent of whites who do not consider themselves southerners.6Andrew Kohut, Carroll Doherty, Michael Dimock, and Scott Keeter, "Civil War at 150: Still Relevant, Still Divisive," Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, April 8, 2011, http://www.people-press.org/2011/04/08/civil-war-at-150-still-relevant-still-divisive/.

But Chief Justice Roberts's question is as immaterial as it is politically charged. At issue is not whether the white South is more biased but whether southern states continue to enact voting schemes, including redistricting plans, that disadvantage African American voters.

Because of the stubborn pattern of racially polarized voting that dilutes the strength of non-white voters, the Supreme Court should consider what have been the mechanisms of change in the South during the last four and a half decades of federal voting rights enforcement. For example, how many southern states have voluntarily enacted statutes and procedures that make voting more convenient for African Americans and Hispanics—populations that are more likely than whites to be low-income? How many southern states voluntarily cleared out their old and new barriers to black and Hispanic voting over the decades without civil rights activist and Justice Department intervention? In how many southern states today are there winning political coalitions in which white, African American, and/or Hispanic voters join at the polls in common cause to elect candidates? The answers: few to none.

In Calera and in the South today, the simple fact remains that when given a choice, most whites will not vote for a candidate (black, brown, or white) who is the open, clear choice of most black or Hispanic voters.

|

| Map of percentage of white voters in 2008 supporting President Obama. |

The simplest illustration of this lingering pattern is found in exit polling in the 2008 presidential election, the last time exit polling was done in all fifty states. In the South, only West Virginia, with an African American population of less than four percent, was among twenty-seven states where whites voted for Barak Obama at or above forty-four percent, the national average of his white support. In eighteen non-southern states and the District of Columbia, a majority of white voters supported Obama in 2008. The nine states with the lowest percentage of white votes for Obama were southern. Alabama had the lowest at ten percent. Six of the seven states completely under the rules of Section 5 had the nation's lowest white voting percentages for Obama.7Stephen Ansolabehere, Nathaniel Persily, and Charles Stewart III, "Race, Region, and Vote Choice in the 2008 Election: Implications for the Future of the Voting Rights Act," Harvard Law Review 123, no. 6 (2010): 1422–1423, http://www.harvardlawreview.org/issues/123/april10/Article_6958.php. Virginia, the seventh covered state, was thirty-nine percent.

The Congress held extensive hearings documenting a continuing need and a persisting pattern of southern resistance to non-white voting before renewing Section 5 and the Voting Rights Act in 2006 for a second time (the first was in 1982). The 2006 renewal had overwhelming, bi-partisan support: no votes against the bill in the Senate and only thirty-three nays in the Republican-controlled House. "The right of ordinary men and women to determine their own political future lies at the heart of the American experiment," stated President George W. Bush when he renewed the Act in July, 2006. "Congress has reaffirmed its belief that all men are created equal."8Raymond Hernandez, "After challenges, House approves renewal of Voting Rights Act," New York Times, July 14, 2006, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/14/washington/14rights.html. "Bush signs Voting Rights Act extension," NBC News, July 27, 2006, http://www.nbcnews.com/id/14059113/ns/politics/t/bush-signs-voting-rights-act-extension.

But, during oral arguments, Justice Scalia suggested he knew the reason for this overwhelming support by the two other branches of the federal government. "Now, I don't think that's attributable to the fact that it is so much clearer now that we need this [Act]. I think it is attributable, very likely attributable, to a phenomenon that is called perpetuation of racial entitlement . . . . Whenever a society adopts racial entitlements, it is very difficult to get out of them through the normal political processes."9Shelby County v. Holder, Oral Arguments, 47.

Scalia's description of the Voting Rights Act as a "racial entitlement" is an outrageous, ahistorical use of language—undertaken by a judge who repeatedly has written that his judicial philosophy is governed by the historical, original intent of the Constitution.

|

| Brian McFadden, "The injustice of racial entitlements," The New York Times Sunday Review, March 3, 2013. |

The US Constitution, written in 1787, provided white southerners with extraordinary political power by counting slaves as three-fifths of persons for purposes of determining representation in the Congress. This "three-fifths compromise" gave the white South oversized political power in both Congress and the Electoral College by allowing white southern men who owned property the opportunity and means to block any legislative effort or Presidential candidate attempting to end slavery. This racial entitlement was the undisputed, original intent of the Constitution.

The three-fifths rule was only for empowering the South and slavery in national politics—not for distributing power within the South's own all-white male politics. At the time of the Constitution's drafting, no southern state government permitted slaveholding southerners to count their slaves in any manner for purposes of distributing political power among whites within state and local governments. And afterwards rarely did any southern state permit such a distortion of a state's political system.

This constitutional entitlement was an essential part of US democracy and politics for more than seventy-five years, until the Civil War and the adoption of the Civil War Amendments—the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth—from 1865 to 1870. These amendments placed into national law five new principles of democracy:

- the abolition of slavery;

- equal rights and privileges of all persons born or naturalized in the United States;

- due process and equal protection of the laws;

- House apportionment based on "the whole number of persons;" and

- "race, color, or previous condition of servitude" cannot be used to deny citizens the right of citizens to vote.

These new democratic entitlements were designed to bring into lawful personhood and US citizenship a specific racial population—the former slaves and their descendants. Yet, these principles had a very brief period in which to take hold before the two national parties agreed to the Tilden-Hayes Compromise of 1876, which signaled the withdrawal of federal protection of these new entitlements for African Americans in the South.10C. Vann Woodward, "Seeds of Failure in Radical Race Policy," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 110, no. 1 (1966): 1–9.

The US Supreme Court did as much or more than the other two branches of the national government to ensure that these new entitlements were annulled in the South, where close to ninety percent of African Americans lived during the last half of the nineteenth century. In the Slaughterhouse Cases, the Court decimated the civil rights laws that Congress had passed to enforce the nation's new constitutional entitlements to protect African Americans in the South from violence and persecution. The Court decision was handed down three years before the Tilden-Hayes compromise. In 1886, the Court held that the word "person" in the Fourteenth Amendment included corporations and afforded them protections while, in keeping with Court opinions, southern states denied the rights of former slaves and their descendants.

In 1896, the Supreme Court decided that the provisions of the Civil War Amendments were not meant to interfere with the southern states' efforts to build a system of racial segregation under the legal pretense of "separate but equal." Plessy v. Ferguson enabled white southerners to proceed for the next half-century to enact and establish Jim Crow segregation.

The Supreme Court not only voided the protections of the Civil War Amendments for African Americans, it provided southern white men more power in national and southern politics than did the three-fifths compromise in the original Constitution. By allowing white-controlled southern states to place disfranchising clauses in their state constitutions, the Court allowed the white South to count black bodies (who like their slave forbearers could not vote) as whole persons—not simply three-fifths—and thereby achieve more clout in national political decision-making than they had before the Civil War under slavery.

Court sanctioned segregation also gave whites in the former slave holding counties of the South the means to have disproportionate political control within their own states. Since political representation now had to be based on all persons, white southerners in majority-black counties counted black citizens fully in aggregating political power without having to count any black votes. This arrangement allowed whites living in the historical Black Belt to control many southern state legislatures for decades.

As political scientist V. O. Key wrote, every white voter registrar became a law unto himself and every southern state and jurisdiction had a wide array of laws, customs, and practices designed to assure that African Americans could not vote or could not have any political influence if they were allowed to vote in small numbers in border South states.11V.O. Key, Jr., Southern Politics in State and Nation (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1949), 563. In 1944, after the Supreme Court reversed its blatant disregard of the Fifteenth Amendment and found in Smith v. Allwright that the all-white primary systems of elections were unconstitutional, very little changed in southern politics. The white South had a vast array of tactics to evade the enforcement of the right to vote.

For more than two decades after Smith v. Allwright, the white South successfully dodged, lied, and manipulated processes and people in a thousand and one different ways to maintain barriers to black voting and black political power. While professing that all adult persons were free to register and vote, local voter registrars frequently changed office hours, required African American applicants to recite whole sections of the federal and state constitutions, kept color-blind records so that no one could count how few African Americans were on the voter rolls, and purged names from voter rolls. The state legislatures and local county governments were equally busy in passing new terms, conditions, and procedures for the same purpose.

|

| Ariel view of marchers crossing the Edmund Pettus bridge during the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, 1965. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, LC-USZ62-126846. |

Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, including Section 5, to put a stop to such deep-seated, malicious mischief. The law passed only after the nation watched newsreels of how, under the command of Governor Wallace, state troopers trampled and beat voting rights protestors crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma's Bloody Sunday. Before and after Selma, many activists were wounded or killed attempting to overturn the denial of black voting rights.

The testimony before Congress in 1982 and 2006 documented that, while violence and official intimidation have largely faded away, efforts to dilute and belittle the voting choices of black citizens in the South have not. As Justice Sotomayor noted, there have been over two hundred violations since 1965 in Shelby County where only one in ten citizens are African American.

If southern history evidences a "racial entitlement" in voting, it has been an entitlement to white southerners—an entitlement that the US Supreme Court sustained, enabled, and enlarged. Efforts to end this entitlement and to provide African Americans with their democratic right to vote met with violence, intimidation, chicanery, custom, and legislation, which the Supreme Court ignored or upheld for most of the nation's history. In recent decades, this resistance to voting rights has diminished, but political resistance unquestionably remains.

"Equality [is] a far more revolutionary aim than freedom," wrote C. Vann Woodward in 1955 in The Burden of Southern History.12C. Vann Woodward, The Burden of Southern History, 3rd ed. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2008), 79. An equality of voting rights means that the power to control society should be equal in every adult person. This radical ideal of democratic power has advanced slowly in the South since 1965, almost exclusively through the persistence of African American citizens buttressed by the federal mechanism of voting rights enforcement.

The Supreme Court will decide before this year's Independence Day which is more important: our constitutional framework of federalism in which each state is equally sovereign in all matters, or our constitutional guarantee of equality in voting. Since it outlawed the all-white primaries in 1944, the Court has recognized that the right to vote involves more than the right to cast a ballot. It includes assuring that a vote does not count less because of race. It took more than a hundred years after adding the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution for southern states to begin to establish a pattern of compliance and respect for the voting rights of black and brown citizens—and only after passage and vigorous enforcement of the Voting Rights Act.

Like old habits of speech and thought, the worst features of southern history linger far longer than we admit. Today we even can hear remnants of the white South's worst past at the Supreme Court, where justices engage in a version of cable television polemics more than informed inquiry. As an institution that for many decades was instrumental in entitling segregated, repressive political power, the Court should now give what the Civil War Amendments authorized and Congress has twice granted when it renewed the Voting Rights Act: the proven, peaceful mechanism by which the South and the nation can move closer to the revolutionary aims of a diverse democracy.

About the Author

A native of Winston County, Alabama, Steve Suitts is an adjunct faculty member of the Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts at Emory University and vice president of the Southern Education Foundation.

Recommended Resources

Text

Ansolabehere, Stephen, Nathaniel Persily, and Charles Stewart III. "Race, Region, and Vote Choice in the 2008 Election: Implications for the Future of the Voting Rights Act." Harvard Law Review 123, no. 6 (2010): 1385–1435. http://www.harvardlawreview.org/issues/123/april10/Article_6958.php.

Flynt, Wayne. Alabama in the Twentieth Century (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004).

Kohut, Andrew, Carroll Doherty, Michael Dimock, and Scott Keeter. "Civil War at 150: Still Relevant, Still Divisive." Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, April 8, 2011. http://www.people-press.org/2011/04/08/civil-war-at-150-still-relevant-still-divisive/.

Tullos, Allen. Alabama Getaway: The Political Imaginary and the Heart of Dixie (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011).

Valentino, Nicholas A. and David O. Sears. "Old Times There Are Not Forgotten: Race and Partisan Realignment in the Contemporary South." American Journal of Political Science 49, no. 3 (July 2005): 672–688. http://web.posc.jmu.edu/seminar/readings/4a-realignment/race+party%20realignment%20in%20the%20south%20old%20times%20not%20forgotten.pdf.

Web

Section 5 Covered Jurisdictions, United States Department of Justice

http://www.justice.gov/crt/about/vot/sec_5/covered.php.

Similar Publications

| 1. | For more information about covered jurisdictions see "Section 5 Covered Jurisdictions," United States Department of Justice, accessed May 21, 2013, http://www.justice.gov/crt/about/vot/sec_5/covered.php. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District No. One v. Holder, Transcript, No. 08-322, 557 US 193 (2009), 195, 202, http://www2.bloomberglaw.com/public/desktop/document/Northwest_Austin_Mun_Utility_Dist_No_One_v_Holder_129_S_Ct_2504_1. |

| 3. | Shelby County, Alabama v. Holder, US Supreme Court Oral Arguments, Transcript, No. 1296, February 27, 2013, 3–4, http://www.supremecourt.gov/oral_arguments/argument_transcripts/12-96.pdf. |

| 4. | Shelby County v. Holder, Oral Arguments, 40–41. |

| 5. | Nicholas A. Valentino and David O. Sears, "Old Times There Are Not Forgotten: Race and Partisan Realignment in the Contemporary South," American Journal of Political Science 49, no. 3 (July 2005): 685, http://web.posc.jmu.edu/seminar/readings/4a-realignment/race+party%20realignment%20in%20the%20south%20old%20times%20not%20forgotten.pdf. |

| 6. | Andrew Kohut, Carroll Doherty, Michael Dimock, and Scott Keeter, "Civil War at 150: Still Relevant, Still Divisive," Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, April 8, 2011, http://www.people-press.org/2011/04/08/civil-war-at-150-still-relevant-still-divisive/. |

| 7. | Stephen Ansolabehere, Nathaniel Persily, and Charles Stewart III, "Race, Region, and Vote Choice in the 2008 Election: Implications for the Future of the Voting Rights Act," Harvard Law Review 123, no. 6 (2010): 1422–1423, http://www.harvardlawreview.org/issues/123/april10/Article_6958.php. Virginia, the seventh covered state, was thirty-nine percent. |

| 8. | Raymond Hernandez, "After challenges, House approves renewal of Voting Rights Act," New York Times, July 14, 2006, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/14/washington/14rights.html. "Bush signs Voting Rights Act extension," NBC News, July 27, 2006, http://www.nbcnews.com/id/14059113/ns/politics/t/bush-signs-voting-rights-act-extension. |

| 9. | Shelby County v. Holder, Oral Arguments, 47. |

| 10. | C. Vann Woodward, "Seeds of Failure in Radical Race Policy," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 110, no. 1 (1966): 1–9. |

| 11. | V.O. Key, Jr., Southern Politics in State and Nation (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1949), 563. |

| 12. | C. Vann Woodward, The Burden of Southern History, 3rd ed. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2008), 79. |