Overview

James E. Fickle reviews Bill Finch, Beth Maynor Young, Rhett Johnson, and John C. Hall's Longleaf, Far as the Eye Can See: A New Vision of North America's Richest Forest (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

Review

|

Longleaf, Far as the Eye Can See presents a rhapsodic argument in pictures and words for the preservation, restoration, and reestablishment of longleaf pine forests across the areas of the US South where they once existed or dominated, ranging from Maryland down and across the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts to east Texas. The book's creators are activists in the longleaf restoration campaign, and the work is supported by the Longleaf Alliance, an organization based at Auburn University and created in 1995 to coordinate cooperation between private landowners, forest industries, government agencies, conservation groups, and researchers. The concept for the book originated with conservation photographer Beth Maynor Young and Longleaf Alliance director Rhett Johnson. Bill Finch, who served as lead writer, is the executive director of the Mobile Botanical Gardens, and John C. Hall is curator of the Black Belt Museum at the University of West Alabama.

|

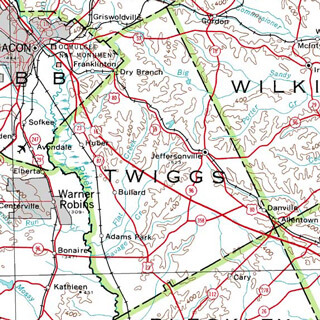

| EPA ecoregions level III and historic range of longleaf pine, Map by Longleaf Alliance. Reproduced by permission of Longleaf Alliance. |

Young's stunning photographs of longleaf forests and flora and fauna, easily the book's outstanding feature, dominate Longleaf's oversized format. The writing, occasionally lyrical, sometimes colloquial, and generally informative, does not rise to the level of the images.

|

| The distinctive shape of a mature longleaf, Weymouth Woods-Sandhills Nature Preserve, Southern Pines, North Carolina. Photograph by Beth Maynor Young. Reproduced by permission of the University of North Carolina Press. |

Once full of diverse plant and animal life, longleaf forests grew in many forms and various conditions and soil types across large areas of the southern states. The authors of Longleaf effectively argue that the forests' diminution has brought a reduction or loss of numerous species, and that fire—both natural and "managed"—is essential.

Some features of the book are irritating. The text breaks on page forty-three for several pages of non-related information and does not resume until page fifty-two. Various experts are mentioned, but the titles of their works are generally not included and there is no formal bibliography. Lawrence S. Earley's Looking for Longleaf: The Fall and Rise of an American Forest, for instance, is an important work that readers should know about.

The authors overlook, exclude, or trivialize some subjects. They treat the important topic of fire as though those who favored fire exclusion were poorly informed zealots, while their opponents were enlightened. The general public has become more aware in recent years, particularly since the Yellowstone fires of 1988, of the importance of fire and fire management in forested areas. But historically, the subject is nuanced and complicated. In the early twentieth century many, if not most, in forestry and land management regarded fire as an unmitigated enemy of forests. Famous anti-fire campaigns featured Smokey Bear. However, foresters such as Yale professor H. H. Chapman, and Austin Cary and Eloise Gerry of the US Forest Service, demonstrated their understanding of fire as a management tool through both their professional work and their writing. The problem was partially one of communication. How do you convey to the public that fire is part of the natural process and that some fire is good, while some is not? And some fire was bad. The authors extoll the wisdom of those who burned to control pests or clear undergrowth, but fail to mention those who set fires to sabotage the property of large landowners and companies, or simply for entertainment. They also do not mention the damage done to young seedlings by wild hogs and the destructive effects of naval stores production.

|

| A manageable fire in a regularly burned longleaf area, Blackwater River State Forest, Milton, Florida. Photograph by Beth Maynor Young. Reproduced by permission of the University of North Carolina Press. |

On the other hand, the authors spotlight some positive examples of longleaf management that are little recognized by the general public. For example, they highlight the role of the military in maintaining large acreages of longleaf on bases such as North Carolina's Fort Bragg, where fires ignited by lightning and ammunition are allowed to burn and contribute to the natural reproductive cycle of the forest. Longleaf also features the stories of individuals and organizations striving to restore or maintain the forest's original domain across the South. In discussing private ownership of forests and wood production, the authors do not account for the enormous changes of recent years with the disappearance of fears of a "timber famine," and the divestiture of vast acreages by forest products companies and their acquisition by investment trusts that are not focused as much on quick regrowth, harvest, and processing of timber as were the lumber and paper companies. Aesthetic and environmental values are important management objectives for some of these newer owners.

|

| Mature longleaf on Sugar Loaf Mountain, Sand Hills State Forest, Patrick, South Carolina. Photograph by Beth Maynor Young. Reproduced by permission of the University of North Carolina Press. |

By emphasizing the biological diversity, beauty, and value of these remarkable forests, this book will help readers "gain a new appreciation for the wonders of the longleaf forest" (x). Hopefully Longleaf will also convince its audience of the imperatives of protection and restoration.

About the Author

James E. Fickle is professor of history at the University of Memphis and Visiting Professor of Forest and Environmental History at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. He is author of Timber: A Photographic History of Mississippi Forestry (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2004) and Mississippi Forests and Forestry (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2001), among other books. His book Green Gold: Alabama's Forests and Forest Industries is forthcoming from University of Alabama Press in early 2014.

Acknowledgements

The photographs included in this review are from Longleaf, Far as the Eye Can See: A New Vision of North America's Richest Forest, by Bill Finch, Beth Maynor Young, Rhett Johnson, and John C. Hall. Copyright © 2012 by the University of North Carolina Press. Photographs © 2012 by Beth Maynor Young. Used by permission of the publisher.

Recommended Resources

Text

Earley, Lawrence S. Looking for Longleaf: The Fall and Rise of an American Forest. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Johnson, Edward A. and Kiyoko Miyanishi, eds. Forest Fires: Behavior and Ecological Effects. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 2001.

Jose, Shibu, Eric J. Jokela, and Deborah L. Miller, eds. The Longleaf Pine Ecosystem: Ecology, Silviculture, and Restoration. New York: Springer, 2006.

Latham, Den. Painting the Landscape with Fire: Longleaf Pines and Fire Ecology. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2013.

Way, Albert G. Conserving Southern Longleaf: Herbert Stoddard and the Rise of Ecological Land Management. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011.

Web

America's Longleaf Restoration Initiative. "America's Longleaf." http://www.americaslongleaf.org.

The Longleaf Alliance. http://www.longleafalliance.org.

National Fish and Wildelife Foundation. "Longleaf Stewardship Fund." http://www.nfwf.org/longleaf.