Overview

Scott Nesbit reviews Gleanings of Freedom: Free and Slave Labor along the Mason-Dixon Line, 1790–1860 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2011) by Max Grivno.

Review

|

Max Grivno's subtle and remarkably textured history of labor in northern Maryland and southern Pennsylvania, Gleanings of Freedom: Free and Slave Labor along the Mason Dixon Line, 1790–1860, details the long decline of slavery in this small region and the ways that enslaved and free labor intertwined. Grivno's account of the antebellum era at its northern reaches is a convincing one. Of great value, too, is his finding that this decline was a product of the connections between this peripheral place and external markets.

Slavery in Maryland was inextricably linked to the booms and busts of nineteenth-century global capitalism. Its decline in Maryland was contingent; farmers only began to turn against slavery as part of a wider process of deleveraging after the end of the Napoleonic wars. As northern Marylanders began to compete in rebounding global wheat markets, they found that their crops were no longer competitive at accustomed prices. With the price of their wheat plummeting, they felt their local economy crash and scrambled to rid themselves of fixed costs of all kinds, including slaves.

The economic crisis of 1819 accelerated processes that had already begun to erode slavery at its northern border. Geographic crosscurrents caught enslaved people at the Mason-Dixon, pulling them northward toward freedom and southward to the emerging cotton fields of the lower South. In dynamic tension, these pulls made slavery especially unstable in northern Maryland. As slaveholders sought to capitalize on the rising market for slaves in the Deep South, slaves became more likely to run away. Border slave-owners and slaves made bargains that mitigated the mutual threats of southward sale and northward escape. They often agreed to term-slavery, delayed manumission, and cash payments for harvest work, extending the life of slavery by modifying it in ways that would have made Maryland wheat fields virtually unrecognizable to those accustomed only to seeing plantations in the Delta or Carolina Piedmont. Whereas in most other places—as the work of Jonathan D. Martin, Calvin Schermerhorn, and others shows—slavery's flexibility was a sign of its continuing strength, Grivno argues that in northern Maryland slavery's increasing plasticity was a mark of its decline.1Jonathan D. Martin, Divided Mastery: Slave Hiring in the American South (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004); Calvin Schermerhorn, Money over Mastery, Family over Freedom: Slavery in the Antebellum Upper South (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Grivno points out that even as slavery eroded, enslaved and free labor regimes proved complementary for owners of capital. Farmers modified slavery in northern Maryland to adapt bound labor to wheat production. Unlike tobacco or cotton, wheat required bursts of intense labor at harvest, followed by relative lulls in activity. In order to maximize their investments in year-round, bound labor, slave-owners hired out enslaved men and women in times of little work and at harvest combined them with members of a large pool of free, landless workers who lived within a hairsbreadth of starvation.

|

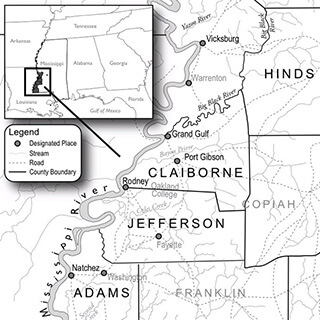

| Alvin Jewett Johnson, "Johnson's Map of Pennsylvania, Virginia, Delaware and Maryland, 1863," from Johnson's New Illustrated (Steel Plate) Family Atlas with Descriptions, Geographical, Statistical, and Historical (New York: Johnson and Ward, 1863). |

These workers lived precarious lives—black workers more precarious than white, female more than male, old more than young. Workers' families spun "webs of dependency" that gave them a chance for survival by pooling resources but vastly extended the devastation wreaked by a single illness, accident, or otherwise unproductive family member (166). Their seasons followed the agricultural calendar of work and want, supplying farmers' needs at the harvest and enduring the void of unemployment in winter months. While in a few cases, the misery endured by black and white laborers created thin strands of sympathy across racial lines, more often white laborers looked for ways to exploit these differences to some meager advantage, whether it was by participating in the capture of fugitive slaves or the kidnap and sale of free black neighbors.

Considering slave and free labor together, Grivno is able to understand antebellum work patterns at multiple scales. As he puts it, "the relationship between slavery and freedom" is like "an image viewed through a lens that is shifting in and out of focus," both as time proceeds and as the historian proceeds through scales of analysis, from "the level of ideological and legal debates" down to "the level of individual workers" (9). The lines between the two statuses blurred but did not disappear, even as slavery in northern Maryland began to fade.

Gleanings of Freedom reveals how wheat fields along the Pennsylvania border were sensitive to European diplomacy and to the price of a slave in Natchez, connections that were not always straightforward. Declining wheat prices led to a backlash against slavery here; rising demand in the Southwest buoyed slave prices in Maryland even as it destabilized the regime, increasing the likelihood that enslaved men and women would run away.

The Civil War marred wheat fields and obliterated the Mason-Dixon line as a border of political consequence. Max Grivno's valuable book teaches us similarities between emancipation and other changes in the labor regimes of northern Maryland: the destruction of slavery was felt but not created here. Emancipation came as an exogenous crash, not the predictable end of a long slide.

About the Author

Scott Nesbit is the Associate Director of the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of Richmond, where he works on projects involving geographic information systems and the humanities, such as Visualizing Emancipation. For the University of Virginia, Nesbit is completing a dissertation on spatial changes attending emancipation.

Recommended Resources

Martin, Jonathan D. Divided Mastery: Slave Hiring in the American South. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

Schermerhorn, Calvin. Money over Mastery, Family over Freedom: Slavery in the Antebellum Upper South. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Jonathan D. Martin, Divided Mastery: Slave Hiring in the American South (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004); Calvin Schermerhorn, Money over Mastery, Family over Freedom: Slavery in the Antebellum Upper South (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011). |

|---|