Overview

John Howard reviews Benjamin E. Wise's William Alexander Percy: The Curious Life of a Mississippi Planter and Sexual Freethinker (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), concluding with an excerpt from the book where Wise considers the complexities of love, sexuality, and place in the early twentieth century.

Review

|

Benjamin Wise's book is a fiercely intelligent yet accessible biography of elite white Delta Mississippian William Alexander Percy (1885–1942), poet, pedagogue, patron of the arts, and author of the influential memoir Lanterns on the Levee, published near the end of his life. Wise remains true to the evidence, excavating a wealth of previously unexamined primary materials, and offering inventive interpretations where the leads are slim, to shed new light on Percy's sexuality.1Full disclosure: I reviewed this book for the press and watched it evolve from a solid praiseworthy Rice University dissertation into an exhilarating path-breaking first monograph of importance for several fields of study. Wise also makes clear the extent to which Percy's race and inherited class privilege made his "experiences of sexual freedom possible. His wealth allowed him to travel around the world, and that wealth was created in large part by black slaves and sharecroppers. His vision of equality . . . not only did not include African Americans; it also depended on them" (199).

With blacks consigned to their paternalistic place and working-class whites thoroughly despised, Percy took up other moral reckonings as his central concern. Wise contextualizes Will Percy’s life, raising some of the largest dilemmas of the times, including war and duty, civic obligations and sexual norms, race and inequality, class and authority, religion and spirituality, place and cultural relativism. Percy wrestled with these thorny dilemmas throughout adulthood. He was a sophisticated thinker and a writer of uncommon creativity. Fortunately, Wise is more than equal to the task. At numerous points I found myself marveling at the subtlety and dexterity of analysis. I learned a great deal in the reading.

With impressive powers of description, Wise builds narrative tension and constructs dramatic arcs without sacrificing complexity. The work strikes a balance between fluid forward-moving storylines and the occasional pauses for reflection and reconsideration. Its erudition is matched by a quality Percy valued: sincerity. It is, by turns, moving and entertaining. It ends like a great novel, with a sense of awe, wonder, and pathos—then closes with a witty and wise epilogue, "On Sex, History, and Trespassing."

William Alexander Percy offers moments to reflect on the partiality of history, the politics of the archive, the distinctive obstacles and obligations of biographers, and the methodological difficulties for historians of emotion, gender, and sexuality. Often with a phrase tucked into a swift-moving passage, Wise reminds readers that we inevitably are left with skewed but revealing accounts of the past. About free-wheeling Florence in the 1920s, Wise describes how the circumspect Percy "became quite close," with scandal-plagued British writer Norman Douglas, "as evidenced by the one letter that survives between them—which, significantly, is not in Percy's papers but in Douglas'" (206). Sometimes the notes expound methodological quandaries, as with the astute observations and critiques of interviews conducted by John Barry and William Armstrong Percy (335, note 45), about the "higher . . . 'burden of proof' for homosex." "Historians," Wise writes, "often assume historical subjects were heterosexual until proven otherwise." These commentaries amount to an extended meditation on history writing while delivering Wise's take on the philosophy of history.

Wise rightly warns readers of assuming autobiographical elements in poetry. With meticulous attention and care in charting broad patterns, he nonetheless shows consistent themes in Percy's life and poetry, as with "An Epistle from Corinth," expertly used to evidence the writer's struggles with particular strands of Christian doctrine, his evolving humanism, and abiding spirituality. Wise offers penetrating analysis of both the poetry's formal conservatism and its thematic innovation. Diary entries and letters are likewise handled with grace and rigor, keen observation and logic. For example, Wise argues that father "LeRoy and Will Percy shared a loving but not emotionally intimate relationship. Leroy had a business approach to seemingly everything in his life save hunting and travelling." Wise evidences this throughout the manuscript. But early on he offers one potent form of evidence: "He signed his correspondence 'LeRoy Percy' whether the letter was to a cotton merchant or to his young son" (36). Later, Wise masterfully employs scant correspondence to reconstruct a trip to Japan, as well as Percy's views on race and the Far East generally (219). In a discursive note, he uses envelope scribblings to instantiate "Percy and his friends' affectionate and campy manner towards one another" (333, n. 31).

Disentangling a complex set of intellectual equivocations, especially around race, Wise demonstrates how Percy could become, in the title's framing, a "sexual freethinker" and cultural relativist, on the one hand, while largely remaining a white supremacist, on the other. Proving this requires taking on some formidable historians.

Wise signals in his introduction (see the excerpt below) that he will challenge interpretations offered by Richard King and Bertram Wyatt-Brown. And in a powerful passage, he jettisons a critique of Percy's poetry as naive, nostalgic, sentimental, and weak, offered by William Faulkner.

Among a host of contributions to any number of scholarly debates, Wise's crisp and clear articulation of Percy's views of love and sexuality will attract the attention of scholars and general readers far beyond the field of southern studies. I've chosen the powerful concluding paragraphs to Wise's introduction to illuminate the larger cultural work of William Alexander Percy.

Excerpt from Benjamin E. Wise's William Alexander Percy

Will Percy believed in the possibility that two men could share love. He believed that intimacy between men was not incompatible with moral decency, and that indeed love between men was virtuous and uplifting. He loved [Harvard Law classmate, New Yorker] Harold Bruff and found in him a confidant, a sounding board, a companion, and an intimate friend. Throughout his life, he maintained intimate relationships with men, though scant evidence remains about the specifics of these relationships. But enough remains that patterns emerge: Percy surrounded himself throughout his life with queer men and women; he frequented places such as the Bowery in Manhattan, the Latin Quarter in Paris, and Taormina in Italy, among others, that were relatively tolerant of queer cultures; and he drew from the idiom of his day to write about and express homoerotic desire in his diaries, letters, poetry, and prose. To read this evidence is to read Percy's lifelong and deliberate attempt to name, understand, and vindicate his own sexuality.

To read this evidence is also to read the reckonings of someone who possessed a high degree of moral seriousness. Percy's ideals about sexuality were never separate from his ethical concerns, his questions about God and the value of life. From college onward, his writings consistently engaged a series of related questions: What is an honorable life? Is there a source of moral authority outside one's own conscience? What is appropriate to do with one's own body, and what is the relationship between pleasure and purity? How can one find meaning in the absence of religious belief? How can one balance a sense of personal freedom with a commitment to the common good? These questions saturated his imagination and framed his personal search for meaning. His attempts to answer them also make up much of his life story.

When Percy wrote in his diary of "our country," he was writing about both a physical location and a kind of understanding he and Harold Bruff shared. When he wrote of "the lands overseas and the haven where I would be," he was writing about Italy, but he was also giving voice to a kind of spiritual and emotional citizenship that emerged during his lifetime. Over this period—quite literally represented by Percy's life span, 1885 to 1942—a monumental shift took place with regard to cultural understandings of sexuality. Specifically, homosexuality emerged as social identity. Before the 1890s in Europe and America, homosexuality was by and large thought of as an act: people spoke of "sodomy," "buggery," and "sexual perversion." Same sex intimacy was understood as an outward expression of deviance, not a manifestation of an inward orientation. It was a violation of God's order; it was not reproductive; it was a sinful decision. In 1885 in Great Britain, the Labouchere Amendment of the Criminal Law Amendment Act outlawed "acts of gross indecency" between men. In the United States, sodomy laws were on the books in every state.

By Percy's death in 1942, these laws were still in place but a cultural shift had taken place with regard to understandings of queer sexual desire and practice. Homosexuality had become an identity—a culture, some would say, a way of thinking, believing, acting, and talking. Men and women during this era attributed to homosexuality an intellectual language, a sensibility. To a degree, homosexuality came to be seen as a manifestation of a personal disposition rather than merely a kind of sexual behavior. "Sex penetrates the whole person," British sexologist Havelock Ellis wrote in 1933. "[A] man's sexual constitution is part of his general constitution. There is considerable truth in the dictum: 'A man is what his sex is.'" By no means was the matter settled, and by no means was this identity homogeneous, but the effect of fifty years of writing by sexologists, anthropologists, poets, and freethinkers such as Oscar Wilde, John Addington Symonds, Edward Carpenter, Margaret Mead, Sigmund Freud, and many others—including Will Percy—was that an ongoing and widely audible cultural discussion had taken root. A new vocabulary was in place. What in the nineteenth century was "the love that dare not speak its name" became by the early twentieth century, to quote one historian, "the love that would not shut up."2Donald H. Mader, "The Greek Mirror: The Uranians and Their Use of Greece," in Same-Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West, ed. Beert C. Verstraete and Vernon Provencal (Binghamton, NY: Harrington Park Press, 2005), 388.

This visibility heightened the indignation of the majority of Americans who continued to view homosexuality as deviant. One reformer in 1904, for example, fretted about "the shoals of painted, perfumed, kohl-eyed, lisping, mincing youths" that seemed everywhere in New York, but he consoled himself that at least they often received "a sound thrashing or an emphatic kicking" from other men.3Quoted in Robert Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Makings of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994), 179. It was against this mentality that Percy and others worked, a context that lent a sense of urgency—and danger—to their project.

Writing and talking about sexuality as a potential form of belonging that transcended local, regional, and national affiliation became common in this era, and Percy participated in and was shaped by this cultural trend. Out of the conviction that same-sex love was natural, he and his contemporaries created a framework of meaning for queer relationships, and this framework gave rise to the cultural identity later called "gay" and "homosexual." Percy and his contemporaries wrote and spoke about a shared understanding, a kind of broader spiritual kinship that was central to this emerging identity. Percy celebrated the gay world and described it as a community of belonging. He figured his own sexual awakening as an entrance into a superior wisdom, a network of human beings who recognized one another and who viewed the world from a different vantage point.

This network existed not just in New York or Paris but also in small southern towns like Sewanee, Tennessee, and Greenville, Mississippi. This is significant, because with a few notable exceptions, scholars of the American South have portrayed the region as devoid of queer sexuality, particularly before 1950. Work on Percy reflects this: McKay Jenkins insists that Will Percy was determined "to remain aloof from the historical pressures of his own time, and to ignore the discomfort of his own sexuality." Bertram Wyatt-Brown argues that Percy was "sexually sequestered" and "closed his eyes to the cultural maze in which he lived." Richard King reads Percy's writing as revealing "a man divided within himself and unable to express openly his essential sexual desires."4McKay Jenkins, The South in Black and White: Race, Sex, and Literature in the 1940s (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 103; Bertram Wyatt-Brown, The House of Percy: Honor, Melancholy, and Imagination in a Southern Family (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 205; Richard H. King, A Southern Renaissance: The Cultural Awakening of the American South (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), 97. Others have discussed Percy’s sexuality in more positive terms, most notably William Armstrong Percy in "William Alexander Percy: His Homosexuality and Why It Matters," in John Howard, ed., Carryin’ On in the Gay and Lesbian South (New York: New York University Press, 1997), 75–92. My treatment of Will Percy picks up on several of the themes in William Armstrong Percy’s 1997 essay. See also Donald Mader, "The Greek Mirror,"; and Kieran Quinlan, "From William Alexander Percy to Walker Percy: Progress or Regress?," European Contributions to American Studies 65 (2006): 143–54. I have come to a different view. The Will Percy I see in the historical record did not ignore the "discomfort" of his sexuality. He did not close his eyes to his world. In Greenville, in Sewanee, in Paris and Boston and New York and Italy, Percy immersed himself in conversations and reading about sexuality and sexual values. He involved himself in the emerging queer subcultures of the early twentieth century. He experienced and enjoyed emotional and sexual intimacy with other men. He faced his world and lived in it—and in doing so, he proved in some ways resourceful and thoughtful, in other ways close-minded and even racist; he called hierarchies of sexuality and gender into question even as he perpetuated those of race and class. His was a sensibility that seems to us at times contradictory, at times ambivalent, at times tenuously prescient.

To understand Percy's life story is to travel with him around the world. It is to track his experience of life in the South but also to journey away from it, to places like Cambridge and Florence and Japan and Samoa, then back to the South again. It is to sit in ecstasy in a Boston theatre with Percy and Harold Bruff; it is to sit in vexed watchfulness at the Washington County Historical Society in Mississippi; it is to ride on trains and steamships, to look out the windows, to wonder with Percy at the world outside. Percy invested the places he experienced with meaning: Greenville, Sewanee, Boston, Paris, New York, and the Mediterranean were not just spaces he traveled through but places that laid claim to his emotions, places whose cultures and institutions and landscapes shaped his experience and imagination. In his life, through his experience in these places, Percy considered and reconsidered, wrote and revised his stories of belonging. To tell his story is to explore a historical contest over the meaning of words in these stories, words like "southern," "homosexual," and "sissy," among others. It is to try to understand someone who can be described as a cultural relativist, sexual liberationist, and white supremacist. It is to watch one person's engagement with God and morality, with history and his place in the world.

This excerpt is from William Alexander Percy: The Curious Life of a Mississippi Planter and Sexual Freethinker by Benjamin E. Wise. Copyright © 2012 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher. www.uncpress.unc.edu.

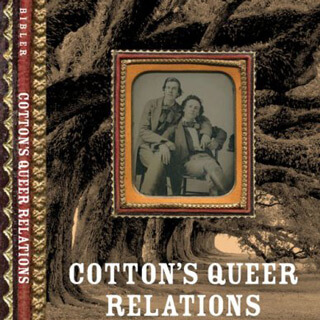

Cover Image Attribution:

Leroy Percy gravesite, October 24, 2004. Photograph by Flickr user Jimmy Smith, Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.Recommended Resources

Baker, Lewis. The Percys of Mississippi: Politics and Literature in the New South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1983.

Chauncey, George. Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940. New York: Basic Books, 1995.

Friend, Craig Thompson, ed. Southern Masculinity: Perspectives on Manhood in the South Since Reconstruction. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2009.

Howard, John, ed. Carryin’ On in the Lesbian and Gay South. New York: New York University Press, 1997.

Jenkins, McKay. The South in Black and White: Race, Sex, and Literature in the 1940s. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

King, Richard H. A Southern Renaissance: The Cultural Awakening of the American South, 1930–1955. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

Percy, Walker. The Message in the Bottle: How Queer Man Is, How Queer Language Is, and What One Has to Do with the Other. New York: Picador USA, 2000.

Percy, William Alexander. Lanterns on the Levee: Recollections of a Planter’s Son. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006.

Wyatt-Brown, Bertram. The Literary Percys: Family History, Gender, and the Southern Imagination. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1994.

———. The House of Percy: Honor, Melancholy, and Imagination in a Southern Family. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Links

Williamapercy.com

A website curated by William Armstrong Percy III, the nephew of William Alexander Percy, and a professor of history at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

http://www.williamapercy.com/wiki/index.php?title=Main_Page.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Full disclosure: I reviewed this book for the press and watched it evolve from a solid praiseworthy Rice University dissertation into an exhilarating path-breaking first monograph of importance for several fields of study. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Donald H. Mader, "The Greek Mirror: The Uranians and Their Use of Greece," in Same-Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West, ed. Beert C. Verstraete and Vernon Provencal (Binghamton, NY: Harrington Park Press, 2005), 388. |

| 3. | Quoted in Robert Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Makings of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994), 179. |

| 4. | McKay Jenkins, The South in Black and White: Race, Sex, and Literature in the 1940s (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 103; Bertram Wyatt-Brown, The House of Percy: Honor, Melancholy, and Imagination in a Southern Family (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 205; Richard H. King, A Southern Renaissance: The Cultural Awakening of the American South (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), 97. Others have discussed Percy’s sexuality in more positive terms, most notably William Armstrong Percy in "William Alexander Percy: His Homosexuality and Why It Matters," in John Howard, ed., Carryin’ On in the Gay and Lesbian South (New York: New York University Press, 1997), 75–92. My treatment of Will Percy picks up on several of the themes in William Armstrong Percy’s 1997 essay. See also Donald Mader, "The Greek Mirror,"; and Kieran Quinlan, "From William Alexander Percy to Walker Percy: Progress or Regress?," European Contributions to American Studies 65 (2006): 143–54. |