Overview

|

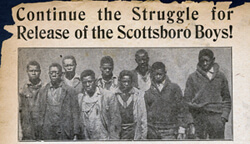

| Daily Worker, Scottsboro headline, 1932. Courtesy of Emory University's Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library. |

In her essay on the March 25, 2011 commemoration activities marking the eightieth anniversary of the Scottsboro Boys' arrests, Ellen Spears reflects on how the Scottsboro trials have been represented and remembered. Spears considers the space of the Scottsboro Boys Museum and Cultural Center as the commemoration setting and the challenges of civil rights memorialization.

Review

|

| Scottsboro, Alabama |

2011 marks the first public commemoration in Scottsboro of the anniversary of the arrests that irrevocably linked the town’s name with Jim Crow. The stories of the nine young black men riding through Alabama on the Depression-era rails from Chattanooga to Memphis in search of work are often obscured today and absent altogether from many high school textbooks. But nearly every major US newspaper covered the events of March 1931 in northeast Alabama. The news of successive Scottsboro trials reverberated globally, prompting demonstrations from Cape Town to Delhi. Then, nearly as suddenly, the cause dropped from view, displaced by a war to extend democratic rights the Scottsboro nine did not enjoy.

The nine young men falsely accused of rape—Haywood Patterson, Clarence Norris, Charley Weems, Olen Montgomery, Willie Roberson, Ozzie Powell, Eugene Williams, and brothers Andrew and Roy Wright—collectively served more than one hundred and thirty years in prison for a crime that did not occur. With a defense team led by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a close affiliate of the US Communist Party, in contentious association with the NAACP, the trials led to landmark Supreme Court decisions. Powell v. Alabama affirmed a defendent's right to competent counsel, and Norris v. Alabama challenged the exclusion of African Americans from jury pools.1Powell v. Alabama, 287 US 45 (1932); Norris v. Alabama, 294 US 587 (1935).

|

| Carol M. Highsmith, Scottsboro Boys Museum and Cultural Center, Scottsboro, Alabama, 2010. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. |

The eightieth anniversary of the arrests brought an unlikely collection of people to Scottsboro: a federal district judge from Detroit; a Broadway producer; a high school teacher from Chicago; the local Jackson County, Alabama, Commission Chair; the state of Alabama’s tourism director; and nearly one hundred fifty more. Each person had a compelling reason for attending, their presence straining the capacity of a local courtroom and a nearby church. Their shared mission in Scottsboro: a commitment to remembrance, a belief that the injustice done the nine young men should not be forgotten. Moreover, as many expressed, remembering Scottsboro could promote racial healing today, still a pressing need.

The commemorative events centered on the Scottsboro Boys Museum and Cultural Center, a new museum that honors the nine defendants, housed in a former African American church. That the Center exists at all is due largely to the persistence of one extraordinary woman. Shelia Washington, who grew up in Scottsboro, had worked for this day ever since her father snatched a book she was reading out of her hand. The forbidden book: defendant Haywood Patterson’s Scottsboro Boy. Washington campaigned for more than seventeen years to build a suitable memorial to the Scottsboro Boys in her home town. In April 2010, the Scottsboro Multicultural Foundation secured a permanent home for the museum, the former Joyce Chapel United Methodist Church, whose congregation had dwindled. Just a few blocks from the city square, the two-thousand square foot brick sanctuary dates from the late nineteenth century. The wooden pews remain. The pastor’s study has become an office and a small annex off the nave now houses documents, memorabilia, and artifacts relating to the trials.

Punctuated by train whistles and the noise of freight cars rolling past—along the same route that carried the young men in search of work in 1931—compelling moments occurred throughout the commemorative day. At the Scottsboro courthouse, county commission chair Sadie Bias welcomed federal district court judge from Detroit, the Honorable Victoria A. Roberts, herself a pathbreaker as a federal judge and the first African American woman to lead the Michigan Bar Association. From the bench where segregationist Judge Alfred E. Hawkins issued the first convictions, Judge Roberts spoke movingly about the continued need for adequate legal counsel.

|  | |

| Ellen Spears, Historian David Carter, Jane Carter, historian Dan Carter, and director Shelia Washington, Scottsboro, Alabama, 2011. | Ellen Spears, Aggie Kapelma announcing the donation of David Scribner's papers, Scottsboro, Alabama, 2011. |

New Yorker Aggie Kapelma presented the museum with documents revealing her father David Scribner’s role in a little known chapter of the Scottsboro story. Scribner was arrested after responding to a ruse designed to entrap the defense team. One of the accusers, Ruby Bates, had recanted her original testimony and had even spoken out at Scottsboro Boys’ defense rallies. Representatives of Victoria Price—who had also accused the nine of rape—enticed members of the defense team working with ILD attorney Samuel Leibowitz to meet with Price in Nashville, implying that she also might recant. Upon their arrival in Nashville, however, Scribner and another junior lawyer were arrested on charges of “attempted bribery,” Kapelma said. Extradited to Alabama to stand trial, the two men were later released.

Also present was Catherine Schreiber, one of the producers of the Broadway musical The Scottsboro Boys, which opened in October and ran until mid-December 2010. The production was simultaneously acclaimed (the play garnered Tony nominations in a dozen categories, including Best Musical) and critiqued as racist for presenting black actors in blackface and retelling the story through the vehicle of the minstrel show. “The actors actually deconstruct the [minstrel show] device in front of the audience, and in the end, rebel against it,” director Susan Stroman explained in response to Freedom Party protests outside New York’s Lyceum Theater during the run.2Patricia Cohen, “‘Scottsboro Boys’ is Focus of Protest,” New York Times, November 7, 2010, accessed May 26, 2011, http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/11/07/scottsboro-boys-is-focus-of-protest/. Co-producer Schreiber and cast members extended significant support to the new museum and used the musical’s high visibility to focus attention on the history of the unjust prosecutions.

|

| The Daily Worker, Drawing of the Scottsboro Boys, 1935. Courtesy of Emory University's Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library. |

Local speakers acknowledged the racial injustice done to the nine teenagers. With a powerful statement, the Benson family, white residents of Jackson County, donated the plot of land that stretches from behind the church to the railroad tracks as a park. Benson Park will extend a view from the museum to the train route. Speaking for the Benson family, John David Hall told those gathered that prominent Scottsboro citizens John Bernard and Elma Kirby Benson “shared, with these tragic young men we remember here, a common humanity and, also, a common sense that justice has not always been done!” Expressing a desire for reconciliation, Hall said, “In their later years, ‘Dad and Mama’ Benson shared with their family and friends their sense that wrongs done by us and others must be corrected and that lessons learned must be shared and passed on.”

“Rights are still being righted,” said Alabama state representative John Robinson, whose district includes several north Alabama counties.

Dozens of young people took part. Dr. Eric Arnall brought video messages—original songs and spoken word performances—from his students at Westcott Elementary School in Chicago. “As an African American young man,” wrote one seventh grader, about the age of the youngest Scottsboro defendant, twelve-year-old Roy Wright, “I could be bitter or better.” The nearly all-black gospel choir from Alabama A&M in Huntsville, rocked the church with “I’ve Been Buked and I’ve Been Scorned;” the nearly all-white choir from Scottsboro High followed. To close out, local musician Franklin McDaniel channeled the wail of the train horn through his harmonica as he played “Amazing Grace.”

|

| Tom Reidy, Pam Farmer's sketches of the nine Scottsboro defendants, Scottsboro, Alabama, 2011. |

Historical memories are complicated. The narratives projected at civil rights heritage tourism sites can be fraught with triumphalism that fails to acknowledge either the full weight of the past or the far-from-fulfilled demands of the present.3Owen J. Dwyer and Derek H. Alderman, Civil Rights Memorials and the Geography of Memory (Chicago: Center for American Places at Columbia College Chicago: Distributed by the University of Georgia Press, 2008); Renee Christine Romano and Leigh Raiford, The Civil Rights Movement in American Memory (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2006). Until now, the main tourism attraction in Scottsboro has been Unclaimed Baggage, bargain mecca for a reported one million tourists each year, plugged on TV by Oprah Winfrey, which sits a block from the new museum. Blending historical interest and expressions of commitment to racial equality with heritage entrepreneurship, Alabama tourism officials are acknowledging the state’s rich concentration of civil rights sites. The marking of physical space in Scottsboro makes memories tangible. Donations of artifacts related to the cases are drifting out of closets and attics—scrapbooks of the trials, intriguing photographs, a juror’s chair, a metal table that came from the old Scottsboro jail, at which the defendants may have taken their meals.

The recovery of memory and of places so long obscured is a material and emotional challenge for the fledgling museum. Physically, many of the sites touched by the multiple trials no longer stand, erased from the cultural geography of north Alabama: the Paint Rock station where the teenagers were pulled from the train and arrested; the old Scottsboro jail where the young men spent their first night in fear of a lynch mob, protected only by Jackson County Sheriff M.L. Wann’s threat to use his pistol on anyone who approached; the Decatur courthouse where Judge James E. Horton made his crucial ruling reversing the verdict against Haywood Patterson (ending any hope of continuing his career as a judge in north Alabama).

|

| Commemorative marker, Scottsboro, Alabama, 2006. |

Beyond the physical challenges, amassing the resources to construct and display a robust collection can meet local objections from people who would just as soon forget injustices. While resistance to remembering the trials is still palpable in Jackson County, the Scottsboro Boys Museum and Cultural Center seeks to be a place of unity and healing from racial wounds. A reconciliation model requires truth-telling, but the history of local responses to the Scottsboro cases was only hinted at on this day. “[G]enuine healing requires a candid confrontation with our past,” wrote historian Timothy Tyson in his 2004 book Blood Done Sign My Name.4Timothy B. Tyson, Blood Done Sign My Name: A True Story (New York: Crown Publishers, 2004), 10. The museum’s founders aim not simply to memorialize the past, but also to embrace a broader mission promoting equity.

Dan T. Carter, who wrote Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South, the definitive account of the trials, sounded a similar theme in his keynote address, urging those present to link the struggles of the Scottsboro Boys to the high rates of incarceration of young African American men and other persons of color today. Despite the civil rights revolution, disparities in sentencing in US criminal courts have become more marked, not less. In the 1930s, black Americans were three times as likely as whites to face jail or prison; by the 1990s, the incarceration rate had more than doubled, making African Americans seven times as likely as whites to do jail time.5Christopher J. Lyons and Becky Pettit, “Compounded Disadvantage: Race, Incarceration and Wage Growth,” Social Problems 58, no. 2 (May 2011): 258.

The handling of the Scottsboro cases kept nine falsely accused young men in the grip of the courts and jails, some for long periods of their lives. In the 1930s, as mass pressure was forcing an end to public lynching, the treatment of the nine defendants foreshadowed a reworked system of social control. Eighty years later, through a network of penal institutions, parole or probation, the criminal justice system oversees one-third of African American men in their twenties.6Dorothy E. Roberts, “The Social and Moral Cost of Mass Incarceration in African American Communities,” Stanford Law Review 56, no. 5 (2004): 1272. The lessons the museum has to draw on are rich, highlighting formative moments in the long black freedom movement that are strongly linked with today's unfinished work.

About the Author

Ellen Griffith Spears is assistant professor in New College and American Studies at the University of Alabama. She is also working with a team of University of Alabama students and a statewide university consortium in partnership with the Scottsboro Boys Museum and Cultural Center, with the support of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Ford Foundation, to further develop educational programming, multi-media exhibits and promotional materials.

Recommended Resources

Carter, Dan T. Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South. New York: Oxford University Press, 1969.

Feldman, Ellen. Scottsboro: A Novel. 1st ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2008.

Goodman, James E. Stories of Scottsboro. 1st ed. New York: Pantheon Books, 1994.

Horne, Gerald. Powell v. Alabama: The Scottsboro Boys and American Justice, Historic Supreme Court Cases. New York: Franklin Watts, 1997.

Kinshasa, Kwando Mbiassi, and Clarence Norris. The Man from Scottsboro: Clarence Norris and the Infamous 1931 Alabama Rape Trial, in His Own Words. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1997.

Miller, James A. Remembering Scottsboro: The Legacy of an Infamous Trial. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Norris, Clarence, and Sybil D. Washington. The Last of the Scottsboro Boys: An Autobiography. New York: Putnam, 1979.

Patterson, Haywood, and Earl Conrad. Scottsboro Boy. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1950.

Pennybacker, Susan D. From Scottsboro to Munich: Race and Political Culture in 1930s Britain. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Film

Scottsboro: An American Tragedy. American Experience, PBS, 2000.

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/scottsboro/index.html.

Links

Cornell Law Library Scottsboro Trial Collections

http://library.lawschool.cornell.edu/WhatWeHave/SpecialCollections/Scottsboro.cfm.

Scottsboro Boys Museum and Cultural Center

http://www.scottsboro-boys.org/.

"To See Justice Done": Letters from the Scottsboro Boys Trials

http://scottsboroboysletters.as.ua.edu.

University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law Page on Scottsboro Trial

http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/scottsboro/scottsb.htm.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Powell v. Alabama, 287 US 45 (1932); Norris v. Alabama, 294 US 587 (1935). |

|---|---|

| 2. | Patricia Cohen, “‘Scottsboro Boys’ is Focus of Protest,” New York Times, November 7, 2010, accessed May 26, 2011, http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/11/07/scottsboro-boys-is-focus-of-protest/. |

| 3. | Owen J. Dwyer and Derek H. Alderman, Civil Rights Memorials and the Geography of Memory (Chicago: Center for American Places at Columbia College Chicago: Distributed by the University of Georgia Press, 2008); Renee Christine Romano and Leigh Raiford, The Civil Rights Movement in American Memory (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2006). |

| 4. | Timothy B. Tyson, Blood Done Sign My Name: A True Story (New York: Crown Publishers, 2004), 10. |

| 5. | Christopher J. Lyons and Becky Pettit, “Compounded Disadvantage: Race, Incarceration and Wage Growth,” Social Problems 58, no. 2 (May 2011): 258. |

| 6. | Dorothy E. Roberts, “The Social and Moral Cost of Mass Incarceration in African American Communities,” Stanford Law Review 56, no. 5 (2004): 1272. |