Overview

|

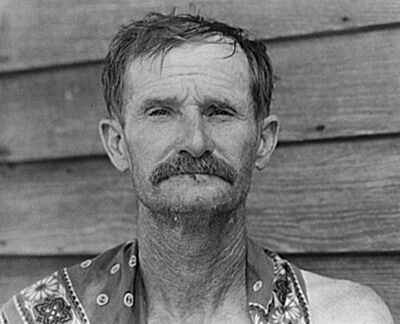

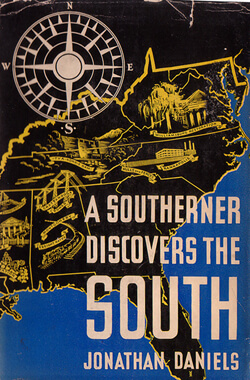

| Book cover from Jonathan Daniels' A Southerner Discovers the South , 1938. |

Jonathan Daniels' ten-state tour, recounted in A Southerner Discovers the South (1938), deserves renewed attention in the context of the documentary ethos of the Depression. Written from the perspective of a privileged and conflicted white southern liberal, Daniels' book appeared soon after Erskine Caldwell and Margaret Bourke-White's sensationalizing You Have Seen Their Faces (1937) and within days of Franklin Roosevelt's declaration of the South as "the Nation's no. 1 economic problem." Daniels' anecdotes, vignettes, and recorded conversations with a variety of well- and lesser-known figures across the political spectrum found resonance with readers. Although A Southerner Discovers the South won praise and became a bestseller, Daniels' mild critique of racism and his call for expanded New Deal programs had little impact against a rising tide of conservative opposition to Roosevelt's reform agenda.

"Dixie Destinations: Rereading Jonathan Daniels's A Southerner Discovers the South" was selected for the 2009 Southern Spaces series "Documentary Expression and the American South," a collection of innovative, interdisciplinary scholarship about documentary work and original documentary projects that engage with regions and places in the US South.

Introduction

I am planning to leave here shortly after the first of May and follow the main street of the new industrial South from Greensboro to Charlotte, Spartanburg and Greenville; then turn to the right and cut through the Great Smoky Mountains National Park to Knoxville; then via Dayton (of monkey trial fame) to Chattanooga and from Chattanooga by Scottsboro, Alabama, through the Tennessee Valley to Memphis; from Memphis through the Marked Tree area where the tenant farmers union was active and on to Little Rock and Hot Springs; from Hot Springs into Mississippi via Greenville, Vicksburg, Natchez and on to Baton Rouge and New Orleans; from New Orleans via Mobile and Montgomery to Birmingham; from Birmingham to Atlanta; from Atlanta down the west coast of Florida to Key West and up the east coast of Florida to Savannah and then home by Charleston and Wilmington.1Jonathan Daniels to Josephus Daniels, 19 April 1937, in Folder 151 of the Jonathan Daniels Papers #3466, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Hereafter Daniels Papers, SHC.

— Jonathan Daniels to Josephus Daniels, 19 April 1937

At 9:37 in the morning on May 5, 1937, Jonathan Daniels, the thirty-five-year-old editor of the Raleigh, North Carolina, News and Observer, set out on a ten-state tour of the South. The odometer of his Plymouth read 22,246.2 miles.2"Notes Made on Southern Tour," p. 1, typescript in Folder 2089b, Daniels Papers, SHC. As he had explained in a letter to his father a few weeks earlier, his planned itinerary was a journalistic roundup, with stops scheduled in the places that had made headlines: Dayton, Tennessee (a 1920s news site Daniels ultimately skipped); Scottsboro, Alabama; Marked Tree, Arkansas.

Daniels' goal was to gather material for a book. In July 1938, he published A Southerner Discovers the South, which became a national bestseller for several weeks and received warm reviews from northerners and southerners, blacks and whites.3Jonathan Daniels, A Southerner Discovers the South (New York: Macmillan, 1938). All references are to this edition. Publishers Weekly listed A Southerner Discovers the South among its "Candidates for the Best Seller List" in its July 30, August 6, and August 20, 1938, issues. The book then made the magazine's weekly and monthly best sellers lists for August and September. Daniels' book sold particularly well in the South, and by early 1939, Frank Porter Graham, president of the new Southern Conference for Human Welfare, would list it alongside Howard Odum's Southern Regions of the United States (1936) and Gerald W. Johnson's The Wasted Land (1937) as a book that had strongly influenced the black and white southern liberals and radicals who were organizing in a nascent political movement.4For the book's popularity in the South, see "The Week's Best Sellers," Publishers Weekly, 3 September 1938, 768. Graham's view, expressed in a letter to Southern Policy Committee founder Francis Pickens Miller, is noted in Patricia Sullivan, Days of Hope: Race and Democracy in the New Deal Era (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 67.

Unlike Odum and Johnson, however, Daniels wrote with neither scholarly authority nor a clearly articulated political agenda — although he would, at the end of his long and discursive narrative, endorse government planning as envisioned by Odum and Johnson and initiated by Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal. Important in its own day but now largely forgotten, A Southerner Discovers the South deserves renewed attention and needs to be understood in the context of the documentary ethos of the 1930s, as well as in relation to its precise political moment in the summer of 1938. By taking to the road, Daniels was following the lead of a number of writers who set out to see the United States in the midst of the Great Depression and who were joined by photographers including, most famously, those employed by the Farm Security Administration. This impulse to document American life grew not only from the political demands of the day, such as the Roosevelt administration's need to justify New Deal programs, but also from observers' efforts to come to terms with the magnitude of the crisis. "Until Fortune published an article in September 1932 called 'No One Has Starved,' establishment newspapers, magazines, and radio programs downplayed or ignored the Depression and portrayed the country, as Hoover himself did, in business-as-usual terms," notes cultural historian Morris Dickstein. "This virtual blackout of bad news gave impetus to the documentary movement, to radical journalism, and to independent films like King Vidor's pastoral fable Our Daily Bread (1934)."5Morris Dickstein, Dancing in the Dark: A Cultural History of the Great Depression (New York: Norton, 2009), 9-10. On the documentary tradition of the 1930s, see William Stott, Documentary Expression and Thirties America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973); John Rogers Puckett, Five Photo-Textual Documentaries from the Great Depression (Ann Arbor, Mich.: UMI Research Press, 1984); Carl Fleischhauer and Beverly W. Brannan, eds. Documenting America, 1935-1943 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988); Michael E. Staub, Voices of Persuasion: Politics of Representation in 1930s America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994); Michael Denning, The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century (London and New York: Verso, 1997), esp. 118-19; and Linda Gordon, Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits (New York: Norton, 2009).

Some such efforts of the early 1930s clearly influenced Daniels, who was working for Fortune in the fall of 1932 and who knew, for example, of Marxist intellectual James Rorty's travels in the South for Where Life is Better: An Unsentimental Journey (1936).6Daniels left Fortune and returned to Raleigh in 1932, but not until after the November presidential election. See Jonathan Worth Daniels, interview by Charles Eagles, 9-11 March 1977, interview A-0313, Southern Oral History Program Collection (#4007), University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, available online in theDocumenting the American South Collection at http://docsouth.unc.edu/sohp/A-0313/menu.html. For Daniels' awareness of James Rorty's travels, see A Southerner Discovers the South, 86-87. Although Daniels included no photographs in A Southerner Discovers the South, his book was often compared to Erskine Caldwell and Margaret Bourke-White's You Have Seen Their Faces (1937), the first of several major Depression-era documentary books with photographs that have had a lasting impact. Assessing Daniels' book in the context of this developing documentary tradition is a major goal of this essay.

In contrast to Caldwell and Bourke-White's politically charged work, Daniels' claim that he was merely reporting on "one man's South" seemed credible, and most readers accepted A Southerner Discovers the South in that spirit.7Daniels, A Southerner Discovers the South, 10. Reviewers praised Daniels for simply being "honest — too honest to pretend to be an oracle."8"A Southerner Discovers the South," Avalanche-Journal, Lubbock, Texas, 17 July 1938, 21. His journalistic style "may disconcert the reader who is hot for certainties," observed Lambert Davis, editor of the Virginia Quarterly Review, but it was the "wisdom" of his method that enabled him "to write a book that is far richer and more humane than any dogmatic approach would have allowed."9Lambert Davis, "Progress below the Potomac," Saturday Review of Literature, 16 July 1938, 5.

Nevertheless, a coincidence of its timing put A Southerner Discovers the South in a unique position that may have made Daniels wish he had written a more politically persuasive work. On July 5, 1938, a New York Times reporter snuck into an empty Washington, DC meeting room at lunchtime and pilfered a copy of a letter that President Roosevelt had sent to an advisory committee of the National Emergency Council. The next day, Times readers learned that the President had declared the South "the Nation's No. 1 economic problem." By July 7, Roosevelt's statement was making headlines and stirring controversy. A Southerner Discovers the South was published on July 12.10The July 12 publication date is mentioned in "Opportune Opus for Dixie," Richmond Times-Dispatch, 19 July 1938, clipping in A Southerner Discovers the South scrapbook, Folder OP-3466/24, Daniels Papers, SHC. On the leak of Roosevelt's letter, see David L. Carlton and Peter A. Coclanis, eds. Confronting Southern Poverty in the Great Depression: The Report on Economic Conditions of the South with Related Documents (Boston and New York: Bedford/St. Martin's, 1996), 19-20; and Steve Davis, "The South as 'The Nation's No. 1 Economic Problem': The NEC Report of 1938," Georgia Historical Quarterly 62 (Summer 1978), 122. It was not long before commentators were linking Daniels' book to readers' need for further information about economic problem No. 1. "It is not the Yankee Pharisee" who is exposing southern poverty, observed a Boston Herald editorial titled "Our 'No. 1 Problem.'" Rather, "it is a young southerner speaking — Jonathan Daniels." Daniels' timing made his book an "opportune opus for Dixie," in the view of the Richmond Times-Dispatch. Not only had Daniels "long been a careful student of Southern problems," but he was also a "progressive, albeit sympathetic, interpreter of the Southern scene." As reviewers asserted, Daniels' background and moderately liberal (although racially segregationist) views made him the ideal person to explain the South to the nation. In the words of John Chamberlain of the New Republic, he was the "critic who comprehends."11"Our 'No. 1 Problem,'" Boston Herald, 17 July 1938, 4, clipping in A Southerner Discovers the Southscrapbook, Daniels Papers, SHC; "Opportune Opus for Dixie," clipping, Daniels Papers, SHC; John Chamberlain, "Swing Around the South," The New Republic, 13 July 1938, 284.

In the fall of 1938, Daniels would capitalize on his authoritative image in three syndicated editorials that purported to answer the question of "What's to Become of the Nation's No. 1 Economic Problem?" He reiterated his faith in New Deal development efforts even as Roosevelt's hopes of extending the New Deal were foundering along with his failed attempt to "purge" the Democratic party of southern conservatives.

The failure of the purge "marked the end of the legislative phase of the New Deal," but as Patricia Sullivan has argued, "the struggle over its political consequences was just beginning."12Sullivan, Days of Hope, 6. The documentary genre was becoming a powerful weapon in the ideological battle over the South's future that was raging at precisely the moment Daniels' book appeared. The close relationship between A Southerner Discovers the South and President Roosevelt's designation of the South as "the nation's No. 1 economic problem" meant that Daniels' anecdotes, vignettes, and recorded conversations with southerners had particular resonance for readers grappling with questions about the South's future.

New Deal Southerner

|

| NEC's Report on Economic Conditions of the South, 1938. Digital version, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. |

Because of his political views and temperament, Jonathan Daniels had no patience for southerners who resented Roosevelt's "No. 1 economic problem" designation. As he wrote to Lowell Mellett, Executive Director of the National Emergency Council (NEC), such critics were the "same old Daughters of the Confederacy — though some in pants — who in all the long years" had been "a more destructive crop than cotton."13Quoted in Sullivan, Days of Hope, 67. Daniels had not worked with Mellett and the NEC, but he was friendly with several of the prominent southerners whom Mellett had assembled in early July 1938 to review a draft of what became the NEC's Report on Economic Conditions of the South. It was this all-southern advisory committee that Roosevelt was addressing in the purloined letter that included his famous phrase. Like University of North Carolina president Frank Porter Graham, Louisville Courier-Journal editor Barry Bingham, and several other members of the panel, Daniels had participated in the Southern Policy Committee (SPC), a "loose network of southern liberals," including one African American, sociologist Charles S. Johnson, who had come together in 1935 and continued to meet and publish papers for the next few years.14Carlton and Coclanis, Confronting Southern Poverty, 11. On the Southern Policy Committee, see also Francis Pickens Miller, Man from the Valley: Memoirs of a Twentieth-Century Virginian (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1971), 81-84; George Brown Tindall, The Emergence of the New South, 1913-1945(Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1967), 592-94; Bruce J. Schulman, From Cotton Belt to Sunbelt: Federal Policy, Economic Development, and the Transformation of the South, 1938-1980 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 40-43; and John Egerton, Speak Now Against the Day: The Generation Before the Civil Rights Movement in the South (New York: Knopf, 1994), 175-77.

SPC members based in Washington, DC, met informally at Hall's Restaurant near Capitol Hill. At one such meeting, a visitor, attorney Jerome Frank of the Power Division of the Public Works Administration (PWA), suggested that the group publish a report about the South. Clark Foreman, director of the Power Division (a Georgian and close contemporary of Daniels), remembered Frank's suggestion in the spring of 1938, when Roosevelt called him to the Oval Office to talk about possible candidates to challenge Georgia Senator Walter F. George, a key target of the anticipated purge. Foreman had not lived in Georgia for a number of years and could not recommend any potential candidates, but he did see potential in a pamphlet reminding southerners of the many ways the New Deal had benefitted them. The Report on Economic Conditions of the South was born amid FDR's planning for the purge, although the President insisted that any such report should merely describe the South's problems rather than prescribing solutions or touting New Deal programs. "If the people understand the facts," Foreman remembered Roosevelt saying, "they will find their own remedies."15Foreman quoted in Davis, "NEC Report of 1938," 121.

|

| Franklin D. Roosevelt and Josephus Daniels at 4-H Tent City in West Potomac Park, Washington DC, 14 June 1940. Courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. |

Jonathan Daniels shared the New Deal vision of Foreman and other SPC members working in Washington. He might have been a government official himself had he not been needed at home in Raleigh to edit the family newspaper, the News and Observer, which his father Josephus had bought in 1894. Born in 1902, Jonathan had long expected to take over from Josephus as editor. He had pursued editorial experience since his high school days in Washington, DC, where the family lived while Josephus served as secretary of the Navy under Woodrow Wilson. Jonathan also edited the Daily Tar Heel while he was a student at the University of North Carolina, where he earned a B.A. and M.A. in English in 1921 and 1922. In 1923 he married and went to work for the News and Observer, where he would spend almost all of his long career.

Especially in his twenties, Daniels had further aspirations. He wrote plays and published one novel, Clash of Angels (1930), but never completed another and seems to have suffered depression after his wife's sudden death in childbirth in 1929.16Lucy Daniels, the second of Daniels's four children, portrays her father as depressed, alcoholic, and emotionally abusive in her intimate memoir, With a Woman's Voice: A Writer's Struggle for Emotional Freedom(Laham, Md.: Madison Books, 2002). Biographical information on Daniels comes from this source; Charles W. Eagles, Jonathan Daniels and Race Relations: The Evolution of a Southern Liberal (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1982); and the Southern Oral History Program interview cited above. From 1930-1932, Daniels worked for Henry Luce's new magazine, Fortune, and also spent sixteen months in Europe on a Guggenheim fellowship. During this period, he met and married Lucy Cathcart, the sister of his friend Noble Cathcart, founding publisher of the Saturday Review of Literature. In early 1933, when Franklin Roosevelt named Josephus Daniels, his close friend and former boss at the Navy Department, ambassador to Mexico, Jonathan became editor of the News and Observer.17On Josephus Daniels' relationship with Franklin Roosevelt, see Carroll Kilpatrick, ed., Roosevelt and Daniels: A Friendship in Politics (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1952).

"a colored boy's friend"

As editor, Daniels quickly developed a reputation for himself and his newspaper as voices of white southern liberalism. Like other white southern liberals of his generation, he remained committed to segregation, a position that would begin to change only during World War II. What made him and his contemporaries "liberals" on race in the prewar era was a desire to see more justice and opportunity for blacks within the segregated system. Whereas various southern radicals, including socialists and communists, worked to unite blacks and whites in a class-based struggle, liberals were reluctant to challenge — and in many instances shared — fellow white southerners' taboos against "social equality." They opposed lynching but were not universally in favor of federal anti-lynching legislation, and they advocated reform in areas such as education, employment, and the quality of racial justice meted out in southern courts.18The scholarship on white liberals and radicals in the pre-World War II South is large. Major works include Wilma Dykeman and James Stokely, Seeds of Southern Change: The Life of Will Alexander (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1962); Morton Sosna, In Search of the Silent South: Southern Liberals and the Race Question (New York: Columbia University Press, 1977); Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, Revolt Against Chivalry: Jessie Daniel Ames and the Women's Campaign Against Lynching (1979; rev. ed., New York: Columbia University Press, 1993); Eagles, Jonathan Daniels and Race Relations; Fred Hobson, Tell About the South: The Southern Rage to Explain (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1983) and But Now I See: The White Southern Racial Conversion Narrative (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1999); John T. Kneebone, Southern Liberal Journalists and the Issue of Race, 1920-1944 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985); Egerton, Speak Now Against the Day; Sullivan, Days of Hope; Anthony P. Dunbar,Against the Grain: Southern Radicals and Prophets, 1929-1959 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1981; John A. Salmond, Miss Lucy of the CIO: The Life and Times of Lucy Randolph Mason, 1882-1959(Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1988); Robin D. G. Kelley, Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990); Robert Rodgers Korstad,Civil Rights Unionism: Tobacco Workers and the Struggle for Democracy in the Mid-Twentieth-Century South(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003); and Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919-1950 (New York: Norton, 2008). In Daniels' case, as in many others, racial liberalism was part of a broader inclination toward economic and cultural "progress" in the South and especially freedom of speech and thought. His focus on race issues intensified over time because whites' efforts to keep blacks down had done so much to keep the South down as well. The South, in turn, was "the Nation's No. 1 economic problem," requiring attention from the federal government and placing a premium on advice from pro-New Deal southern experts — the same politically connected white male liberals who formed the Southern Policy Committee and wrote the NEC Report on Economic Conditions of the South. Recent scholars are correct in seeing the most fertile "seeds of southern change" and particularly the origins of the long civil rights movement in a black-left-labor coalition rather than among white southern liberals.19On the importance of the black-Left-labor coalition, see esp. Jacquelyn Hall's influential "The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Political Uses of the Past," Journal of American History 91 (March 2005), and Gilmore, Defying Dixie. Nevertheless, the liberals' political influence in the New Deal era mattered, reshaping the relationship between the South and the nation by the early 1940s.

For white southerners such as Daniels, political connections could be a limiting as well as an enabling factor. Jonathan Daniels' position as a white southern liberal was complicated by the fact that he was the prominent son of an even more prominent father who was no liberal on race. In the 1890s, Josephus Daniels had used the News and Observer to lead a vicious campaign to disfranchise North Carolina's black voters. "Then, as secretary of the Navy," Glenda Gilmore adds, "he had exported Jim Crow to Haiti" during a long US occupation that began in 1915. Gilmore quotes one black southerner who considered the elder Daniels an "unspeakable Southern bureaucrat" with an "anti-Negro virus." W. E. B. Du Bois accused him of "carrying on a reign of terror, browbeating, and cruelty at the hands of southern white naval officers and marines."20Gilmore, Defying Dixie, 22. On his role in the North Carolina white supremacy campaign, see also Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896-1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), esp. 83-84, 88-89. Little wonder that Josephus preferred not to discuss the "race question" or that Jonathan broached the subject cautiously. "I hope that I am not making your paper too much of a colored boy's friend," he wrote his father in July 1933. In his first weeks as editor, he had written about black poverty, lynching, and racial bias in the justice system. "Josephus Daniels did not object to any of the editorials in particular," biographer Charles Eagles explains, "but his son simply knew that his father would not have written them."21Eagles, Jonathan Daniels and Race Relations, 3.

Even as he departed from his fathers' views, Jonathan Daniels maintained his own prejudices. When University of North Carolina English professor Eston E. Ericson publicly dined with Communist Party vice-presidential candidate James W. Ford in October 1936, Daniels wrote a scolding editorial denouncing Ericson's action, not because Ford was a communist, but because he was black.22Eagles, Jonathan Daniels and Race Relations, 45-50.

Because of criticism he received from more progressive friends such as UNC Press director William T. Couch, Daniels began to reevaluate his racial views in the wake of the Ericson controversy. Over time, he would accept integration, approving of Pauli Murray's failed bid for admission to graduate school at UNC in 1939 and supporting new civil rights laws and their enforcement in his News and Observer editorials in the 1950s and 1960s.23On his willingness to see Murray admitted to UNC, see Gilmore, Defying Dixie, 278. His civil rights era positions are outlined in Eagles, Jonathan Daniels and Race Relations, chs. 6 & 7. As of 1938 when he published A Southerner Discovers the South, however, Daniels was still hesitant and "spoke with much the same ambivalent voice as did his moderate-to-liberal colleagues in the press. . . The contradictions of the culture were mirrored in his own vacillating shifts from narrow paternalism to occasional flashes of genuinely democratic and egalitarian conviction."24Egerton, Speak Now Against the Day, 259. Although a vanguard of white southerners such as Lillian Smith would manage to ignite sparks that were visible beyond the South by the mid 1940s, Daniels' dimmer and less frequent points of light were enough to earn him a reputation as a progressive. Writing in 1938, black educator Benjamin Brawley asserted that "in general," Daniels had "become known within recent years as one of the most forward-looking spirits of the South."25Benjamin Brawley, "A Southerner's Travels at Home," Journal of Negro Education 7 (October 1938), 553.

"the man for the job"

This was the Jonathan Daniels who came to mind when Harold Strauss, an editor at the New York publishing firm Covici-Friede, went looking for someone to write a non-fiction "prose epic" about life in Tennessee. Apparently influenced by contemporary Appalachian stereotypes, Strauss envisioned a book that would start "up in the hills with the old-time mountaineers completely cut off from civilization" and end with the coming of the Tennessee Valley Authority — and with it, he implied, the dawn of enlightenment in the area. "It may be necessary to invent typical characters, such as mountaineers, industrial workers and farm workers; and at other times it may be necessary to rely pretty much on factual exposition," Strauss wrote to Daniels in February 1937. This "combination of fact and fiction" was what made Strauss think Daniels "may be the man for the job," "one of the few men in the country who could do the book the way it should be done."26Harold Strauss to Jonathan Daniels, 25 February 1937, in Folder 151, Daniels Papers, SHC.

Daniels was intrigued, in part because, as he approached thirty-five, he felt he had not lived up to his own ambitions as a writer. "Sometimes it seems to me that I never will get anything done," he confided to Josephus. "It has been seven years since my novel was published and that makes me look like a complete dud."27Jonathan Daniels to Josephus Daniels, [27 February 1937?], in Folder 151, Daniels Papers, SHC. Jonathan may have been depressed about his prospects as a writer, or he may have been trying to soften up Josephus, whose support he would need for any project that took him away from the helm of the News and Observer. Either way, he quickly embraced the idea of writing a book. How that book changed from a "prose epic" about Tennessee to a combination travelogue and political and cultural analysis of the entire region is not quite clear. A New York City lunch with influential friends from the Saturday Review of Literature played some part in reshaping the proposed project — and taking it away from Covici-Friede. Daniels was so well connected in the publishing world that soon Harper's was trying to outbid Macmillan for the book, a situation that compelled Macmillan to offer a sizeable $1000 advance.28Daniels mentions the lunch in A Southerner Discovers the South, 2. On the contract negotiations, see Jonathan Daniels to Josephus Daniels, 19 April 1937, in Folder 151, Daniels Papers, SHC.

By mid April 1937, Daniels was making plans for his journey. "In order to reduce the expenses of 'discovery', I have been planning all along to make the trip in connection with the Southern Newspaper Publishers Convention at Hot Springs, Arkansas, in May," he wrote to his father.29Jonathan Daniels to Josephus Daniels, 19 April 1937, in Folder 151, Daniels Papers, SHC. "My present plan is to leave here on May 5th. . . .That will give me 12 days for Piedmont industry, Great Smoky Park, TVA, Memphis and tenant farmers union, and Little Rock. Lucy, who has been going over maps almost as much as I have, figures that if the rest of the trip takes proportionately as much time the whole journey will take from 6 to 8 weeks."30Jonathan Daniels to Josephus Daniels, 26 April 1937, in Folder 151, Daniels Papers, SHC. Daniels wrote "Little Rocky" but I have standardized the city's name for clarity. In fact, Daniels was home again in roughly five.31The journal Daniels kept during his trip ran from May 5 through June 7 but ended with Daniels in Florida. It is unclear how many more days it took him to return to Raleigh or whether he followed the route described inA Southerner Discovers the South. See "Notes Made on Southern Tour," Daniels Papers, SHC.

"a survey of the present South"

The lightning pace at which Daniels "discovered" the South raised one reviewers' eyebrows after the book appeared. Vanderbilt University history professor Frank Owsley thought Daniels must have "covered the second half of the journey — New Orleans to Raleigh — at the rate of five hundred miles a day" — an overestimate, but Owsley was certainly correct that Daniels devoted even less time to Georgia, Florida, and the coastal Carolinas than to the first six states he visited. Because of Daniels' haste, Owsley complained, A Southerner Discovers the South was "based upon inadequate reporting; the word incompetent might be a better adjective."32Frank L. Owsley, "Mr. Daniels Discovers the South," Southern Review 4 (1939), 666.

|

| Title page and list of delegates from Southern Policy Committee's Report of the Southern Policy Conference Atlanta, Georgia, 25-28 April 1935. |

As a Nashville Agrarian, Owsley was predisposed to be hostile because he associated Daniels with sociologists Howard Odum and Rupert Vance and other Chapel Hill Regionalists. Centered at UNC's Institute for Research in Social Science, the Regionalists analyzed the South's economic and social problems in the 1920s and 1930s. Their findings pointed to a pattern of waste of both human and natural resources, a pattern that Odum described statistically in Southern Regions of the United States (1936) and journalist Gerald W. Johnson explained for a broader audience in The Wasted Land (1937). A key part of the white southern liberal tradition, the Regionalists were the guiding force of the Southern Policy Committee, extending their academic research into a political philosophy that emphasized the need for social planning to bring about the South's economic and cultural development.

This philosophy was fundamentally opposed to that of the Agrarians, who had come together at Vanderbilt at roughly the same time the Regionalist group was forming at Chapel Hill. As they explained in I'll Take My Stand (1930) and later works, the Agrarians rejected any effort to turn the South into a modern industrial society and instead celebrated agriculture and southern tradition. Although they tried initially to bring their views into the SPC, they lost the intellectual debate to the Regionalists and departed from the organization in a huff.33Scholarship on both the Regionalists and the Agrarians is extensive. Major works include Daniel Joseph Singal, The War Within: From Victorian to Modernist Thought in the South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982); Michael O'Brien, The Idea of the American South, 1920-1941 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979); Paul K. Conkin, The Southern Agrarians (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1988); Mark O. Malvasi, The Unregenerate South: The Agrarian Thought of John Crowe Ransom, Allen Tate, and Donald Davidson (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997); Paul V. Murphy, The Rebuke of History: The Southern Agrarians and American Conservative Thought (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001); Emily S. Bingham and Thomas A. Underwood, eds. The Southern Agrarians and the New Deal: Essays After I'll Take My Stand (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2001); and Michael O'Brien, Placing the South (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2007). It is no surprise that Owsley would write a scathing review of A Southerner Discovers the South, which retailed Regionalist arguments, particularly in its concluding chapter. Moreover, Owsley was right that Daniels' 1937 tour was cursory. A few other reviewers, including scholars Avery Craven and Paul Buck, found Daniels' survey of the South "superficial," although mass-media critics typically praised the book's breadth without questioning its depth.34Avery Craven, review of A Southerner Discovers the South in American Journal of Sociology 44 (March 1939), 774-75; Paul H. Buck, review of A Southerner Discovers the South in Mississippi Valley Historical Review 25 (March 1939), 579-80.

Daniels' book is best understood as a mix of analysis and "discovery," or as Craven remarked, as a "survey of the present South by a man who sees more deeply from earlier reading than from direct observation."35Craven, review in American Journal of Sociology, 775. His journalistic itinerary and "letters of introduction to" (as he put it somewhat facetiously) "the best — the very best — people" indicate that he had a mental geography of his South well mapped before he left Raleigh.36Daniels, A Southerner Discovers the South, 11. Daniels described the physical landscape he encountered, often copying his observations almost verbatim from his journal. He also described people: people he saw from his car window, people he talked to at gas stations and restaurants, people he gave rides and quizzed about their lives along the way. The heart of the book, though, was Daniels' accounts of his prearranged meetings with well-known figures across a wide political and cultural spectrum. Some of the more famous were David Lilienthal, co-director of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA); Donald Davidson, Agrarian poet and scholar; J. R. Butler and William Amberson, president and key intellectual supporter of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU); Sam Franklin, leading light of a Christian socialist agricultural cooperative at Hillhouse, Mississippi; William Alexander Percy, David Cohn, and Roark Bradford, Mississippi writers whom Daniels met together at Percy's home in Greenville; Oscar Johnston, head of the immense cotton plantation empire owned by the British corporation Delta Pine and Land; William Mitch, organizer for the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO); Charles F. DeBardeleben, Birmingham mining magnate; and — in a sexist age, the only woman Daniels made an effort to see — Margaret Mitchell. Gone with the Wind had been flying off bookstore shelves for almost exactly a year and had not yet been turned into a movie when they met on June 5, 1937. Remarkably, Daniels never named Mitchell in his book, even though he reported some of their lunchtime conversation.37For Daniels's conversation with Mitchell, see "Notes Made on Southern Tour," Daniels Papers, SHC.

Although Jonathan Daniels learned from his travels, he looked for and saw much that he expected to see: the restlessness rather than much-proclaimed docility of southern industrial workers; the benefits of the TVA despite his own professed skepticism about planned communities such as Norris, Tennessee; the devastating effects of soil erosion, deforestation, and the boll weevil and the need for better stewardship of the land and other natural resources; the weaknesses in southern political and intellectual leadership, including that of the out-of-touch Agrarians; the intractability of the problems in southern agriculture as exemplified by the ongoing struggles of the STFU in Arkansas and the inefficiency of both government resettlement efforts and Franklin's cooperative at Hillhouse; the passing of paternalistic aristocrats such as Percy; the rising fear and antagonism between elites and poor whites; the preference of many white southerners to escape to a tragic past that, to their minds, excused present inaction; and the growing hunger for consumer goods among the black and white southern masses that, in Daniels' view, promised to transform the South more than any government planning or the stirrings of socialists or communists or labor unions in the region. Ideas that Daniels was not ready for — such as integration and equal citizenship for blacks — did not come up because they were not on his map. His itinerary did not include the five-year-old Highlander Folk School or the prison cells of the Scottsboro Boys or other locations that might have forced him to consider more radical visions of the South's future.38On Highlander Folk School, see John M. Glen, Highlander: No Ordinary School, 1932-1962 (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1988); and Aimee Isgrig Horton, The Highlander Folk School: A History of Its Major Programs, 1932-1961 (New York: Carlson, 1989). On the Scottsboro cases, see Dan T. Carter,Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1969); James Goodman, Stories of Scottsboro (New York: Random House, 1995); and James R. Acker, Scottsboro and Its Legacy: The Cases That Challenged American Legal and Social Justice (Westport, Conn. and London: Praeger, 2008). When a conversation at Tuskegee Institute compelled him to contemplate racial violence and oppression, he was troubled but remained noncommittal. He took Tuskegee off his map to the extent that he never recounted his visit in A Southerner Discovers the South — presumably to protect the school and the men he talked to, whose revelations he attributed to anonymous sources. Tuskegee remained on the map printed in the book, but readers learned nothing about the place or its people, apparently the only blacks Daniels had planned in advance to meet.39For Daniels' visit to Tuskegee, see "Notes Made on Southern Tour," Daniels Papers, SHC.

In short, Daniels made an effort to describe a land and its people, but it was the mental geography of his South that mattered most. He measured people and places against their reputations and for their roles within a story that he felt he already understood. When it came time to write his book, which he completed within a few months of his return, he frequently subordinated geography to other concerns. He molded his depictions of individuals into types and often drew composites or put the words of one person he had met into the mouth of another or of an anonymous, sometimes fictional speaker. Having discussed most of the themes that interested him in his first two dozen chapters, he seems to have felt only minimal obligation to describe the locales mapped out on his homeward journey. His travel diary includes no notes about his trip from Tampa back to Raleigh.40See "Notes Made on Southern Tour," Daniels Papers, SHC. Although contemporary reviewers made a point of summarizing Daniels' itinerary, the route by which he had "discovered" his South was both longer (intellectually) and shorter (as a journalistic expedition) than it appeared.

None of the major reviews of A Southerner Discovers the South noted that Daniels "began" his journey in two different places, both Raleigh, where he actually started, and Washington, DC. "You come south from anywhere through Washington," he wrote in a chapter titled "Beginning in a Graveyard." "You turn into the long Memorial Bridge. Look up, then, and see it upon the hill. Arlington by any seeing must be the façade of the South" (an interesting choice of words; he also called Arlington the South's "front door").41Daniels, A Southerner Discovers the South, 12. But Daniels, the North Carolinian, had no need to "come south," and his very brief and undated notes on the drive from Raleigh to Washington (not vice versa) appear on the final page of his journal.42See "Notes Made on Southern Tour," Daniels Papers, SHC. To pretend he started at Arlington was to address a mythology of the South associated with Robert E. Lee, whose former home at Arlington was "the most easily seen thing on the whole road south," Daniels asserted. "And beyond it nothing is simpler for the simple than imagining a whole succession of Arlingtons in which good masters in the tradition of Lee live and preside over the pleasant destinies of the happy colored folks." This legend was false, but sometimes it was seen as "so glamorously false that it has led all the way to equally wonderful legends in repudiation. And then the Southerner seems a fetid frog capable only of ejecting the brown sputum of snuff or tobacco into the deep sand of the twisting road."43Daniels, A Southerner Discovers the South, 12-13. With this allusion to Erskine Caldwell's Tobacco Road (1932), Daniels positioned himself between southern patriots and one of the South's best-known and most sensational critics. By 1937, Tobacco Road and God's Little Acre (1933) had sold by the thousands and a stage adaptation of Tobacco Road was well into the seven-and-a-half-year run that would make it "the longest-running play on Broadway."44Dickstein, Dancing in the Dark, 96. See also Dan B. Miller, Erskine Caldwell: The Journey from Tobacco Road (New York: Knopf, 1995). Equally significant, Caldwell and photographer Margaret Bourke-White published You Have Seen Their Faces in November 1937, just as Daniels was completing his book.

An Emerging Documentary Ethos

|

| Book cover from Erskine Caldwell and Margaret Bourke-White, You Have Seen Their Faces, New York: Viking Press, 1937. |

Traveling around the South in the summer of 1936, Caldwell and Bourke-White had sought out the poorest black and white southerners, those Caldwell described as "struggling souls, living on tenant farms which are only clay deposits and sand dunes . . . the million and a half families . . . being bred and crushed in a land without hope."45Quoted in Miller, Erskine Caldwell, 232. You Have Seen Their Faces combined dozens of Bourke-White's photographs of these people and their dilapidated homes and eroded fields with six short essays by Caldwell on the evils of the sharecropping system. The book also included first-person captions that Caldwell and Bourke-White wrote together to express, not their subjects' actual words, but their "own conception of the sentiments of the individuals portrayed."46Erskine Caldwell and Margaret Bourke-White, You Have Seen Their Faces (New York: Viking, 1937). Although the plight of the sharecropper had been the subject of many previous books and magazine articles by 1937, You Have Seen Their Faces was an immediate sensation, not only a bestseller but thought to represent, in the words of prominent critic Malcolm Cowley, "a new art."47Malcolm Cowley, Review of You Have Seen Their Faces, New Republic, 24 November 1937, 78.

Of course, documentary books with photographs were not a new genre, having been pioneered by Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine a few decades earlier. Nevertheless, You Have Seen Their Faces began "a five-year spurt of creativity in this genre" that included such well-known books as Dorothea Lange and Paul S. Taylor's American Exodus (1939) and culminated in the publication of James Agee and Walker Evans's 1941 Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.48Stott, Documentary Expression and Thirties America, 213. Like Caldwell and Bourke-White, Agee and Evans had started their work in 1936 (on assignment for Fortune), but it took five content/ious years and negotiations with two publishers for their book to appear. As a result, You Have Seen Their Faces was the only one of the era's major photo-textual documentaries that came out prior to A Southerner Discovers the South (former Agrarian Herman Clarence Nixon's Forty Acres and Steel Mules appeared almost simultaneously in 1938). Even on its own, Caldwell and Bourke-White's book was important enough to shape the context in which A Southerner Discovers the South would be received. Daniels had not taken any pictures for his book, but he did travel with Life magazine photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt in early 1938 in what seems to have been something of a make-up effort on his part.49On Daniels's travels with Eisenstaedt, see "Author Jonathan Daniels Inspects Atlanta's Scenery," Atlanta Journal, and similar clippings in A Southerner Discovers the South scrapbook, Daniels papers, SHC. In addition, reviews of A Southerner Discovers the South not only referred to You Have Seen Their Faces, but in at least one case made Daniels' book seem similar to it by printing a photograph taken by a Farm Security Administration photographer alongside the review.

Caldwell and Bourke-White's goals in documenting southern poverty were very different from Daniels' goals in his expedition of "discovery." The left-leaning son of a Georgia minister, Erskine Caldwell was genuinely outraged by the desperate situation of southern sharecroppers. But he also conceived of You Have Seen Their Faces as a way "to show that the fiction I was writing was authentically based on contemporary life in the South" and to marshal photographs to prove it.50Erskine Caldwell, Call It Experience: The Years of Learning How to Write (1951; Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1996), 163. Yet, as Daniels complained about all of Caldwell's work, the book's representations of poverty and degradation made the specific seem general, as if virtually all southerners or at least all tenant farmers lived in the same utterly abject conditions. More important, You Have Seen Their Faces robbed its subjects of their dignity. Many of Caldwell and Bourke-White's captions spoke of defeat or suggested that sharecroppers lacked insight into the nature of their exploitation. Placing the words "I get paid very well. A dollar a day when I'm working" beneath the image of a scruffy and toothless, yet grinning man suggested that he was incapable of understanding his victimization at all. Caldwell's text was passionate and even informative, but not original or insightful in an era that saw many southern exposes. His primary recommendation for improving the sharecroppers' lot was that a government commission should study the problem — something the Roosevelt administration had already done.

What made You Have Seen Their Faces seem original — and what made it sell — was its photographs. "At one time there must have been a copy . . . in every 'progressive' household in America, and in many other homes as well, if only as an act of piety toward the southern poor," Morris Dickstein has recently reflected. "Yet I wonder how many people actually read the book. . . . Caldwell's modest text was not what they were looking at."51Dickstein, Dancing in the Dark, 99. One of the most successful and highly paid photojournalists of her era, Margaret Bourke-White was a master at capturing the expressions and postures that made her subjects look most vulnerable, most defeated. Sitting in the background with a remote control connected to her camera's shutter, she "watched our people while Mr. Caldwell talked," as she explained in her "Notes on Photographs" at the end of the book. "It might take an hour before their faces or gestures gave us what we were trying to express," she admitted (with no apparent sense of irony), "but the instant it occurred the scene was imprisoned on a sheet of film before they knew what had happened."52Caldwell and Bourke-White, You Have Seen Their Faces, 187. Bourke-White's use of bright light and heavy shadow frequently "imprisoned" her subjects still further. As one scholar notes, "Such lighting is often used in horror movies to create a sinister atmosphere and to accentuate an evil face." Bourke-White used it to make her subjects look pathetic and "to accent sick and malnourished bodies."53Puckett, Five Photo-Textual Documentaries, 33.

The effect was moving to many readers, but maudlin and exploitative to others. While reviewers for major national publications heaped praise on the book, white southerners, including liberals like W. T. Couch, panned it. "If we ever pass out of the present era of sentimental slush, or undiscriminating sympathy on the one hand and . . . merriment over psychopaths on the other," Couch wrote, "Mr. Caldwell's works will be forgotten." Other documentarians also disliked the book. "Have You Really Seen Their Faces?" was the caption H. C. Nixon chose for the photographs, mostly of "smiling, robust sharecroppers," in Forty Acres and Steel Mules. "Quotations which accompany the photographs report what the persons photographed said," Dorothea Lange and Paul Taylor pointedly assured readers of American Exodus, "not what we think might be their unspoken thoughts." Among the book's sharpest contemporary critics were James Agee and Walker Evans, who considered it a "double outrage: propaganda for one thing, and profit-making out of both propaganda and the plight of the tenant farmers" for another.54For these and other critical reactions to You Have Seen Their Faces, see Miller, Erskine Caldwell, 239-41. Evans's comparatively non-manipulative photographs and Agee's more humane and empathetic treatment of sharecroppers in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men have made it difficult for subsequent critics to forgive the ways in which Caldwell and Bourke-White's simplistic and sentimental portraits humiliated their subjects. Both "profoundly controversial and influential,"55Robert E. Snyder, "Erskine Caldwell and Margaret Bourke-White: 'You Have Seen Their Faces',"Prospects 11 (1986), 393-94. You Have Seen Their Faces was the main reference point against which A Southerner Discovers the South was measured.

It was a reference point from which Daniels pushed away. Whereas Caldwell and Bourke-White's very title accused the reader of having failed to act on knowledge he or she already possessed — You Have Seen Their Faces — Daniels' tone was affable and unchallenging. Historian William E. Leuchtenburg, who first read A Southerner Discovers the South as a fifteen-year-old growing up in Queens, New York, felt that Daniels really was embarking on a voyage of discovery, "with the reader, as unseen passenger in the car, invited to tag along."56William E. Leuchtenburg in Books of Passage: 27 North Carolina Writers on the Books that Changed Their Lives, ed. David Perkins (Asheboro, N.C.: Down Home Press, 1996), 112. Thanks to Daniel McInerney for bringing this source to my attention. Daniels also emphasized his own inexperience, making it all the more possible for the reader to reach conclusions along with him — although Daniels had reached many of his conclusions before he ever set out. "My virtue, if any, as commentator lies in my comparative ignorance," he wrote, not entirely dishonestly, in his first chapter. "Here I am, Southern bred and born, educated at Chapel Hill, making my living in Raleigh by commenting on the variations and vagaries of the Southern scene . . . [but] until this trip I had hardly been south of my own State of North Carolina. . . . I think, therefore, that I can look at the South with some detachment."57Daniels, A Southerner Discovers the South, 7-8.

Daniels' promise of dispassionate observation — a promise that utterly ignored his privileged class and race position — made A Southerner Discovers the South a documentary characteristic of its era, which saw many books in the "I've Seen America" mold.58On the "I've Seen America" documentary subgenre of the late 1930s, see Stott, Documentary Expression and Thirties America, ch. 13. "There are as many Souths, perhaps, as there are people in it," Daniels added, echoing the sentiments of a number of contemporary writers who had said the same of the United States as a whole. "And, since the traveler is generally the same man at the end of the journey," Daniels continued (a rather troubling statement from someone in the business of discovery), "here may be only one man's South."59Daniels, A Southerner Discovers the South, 9-10.

"the best book about the modern South"?

Daniels' South was idiosyncratic, but readers considered it accurate and found the book engaging. Not only was the "barrage of publicity" extensive, marveled the Richmond Times-Dispatch, but the reviews "were overwhelmingly favorable in their judgments. The consensus of several was that the book is the best which has been written about the modern South."60"Opportune Opus for Dixie," clipping, Daniels papers, SHC. Daniels' travelogue format and easy, journalistic style were major reasons for its appeal. Caldwell and Bourke-White's You Have Seen Their Faces, Odum's Southern Regions of the United States, and Agrarian Donald Davidson's Attack on Leviathan each excelled A Southerner Discovers the South in its "special field," wrote journalist Gerald Johnson, but "whereas each of the others was aimed at a different group, more or less specialized in its interests, Mr. Daniels aims at any one who can read."61Gerald W. Johnson, "Here is the Best Book on the Modern South," New York Herald Tribune, 17 July 1938, clipping in A Southerner Discovers the South scrapbook, Daniels Papers, SHC. Even somewhat critical reviewers like historian Paul Buck valued the book's readability. Although Buck felt Daniels' book lacked "the penetration" of the NEC Report on Economic Conditions of the South, "the detail" of a Works Progress Administration (WPA) state guide, and "the program" of Odum's Southern Regions, he nonetheless praised A Southerner Discovers the South as "a sensible, moderately liberal, and interesting description of the South and its problems. As such it carries its message to a much wider public than scholars directly can hope to reach."62Buck, review in Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 580.

|

| Arthur Rothstein, students in the greenhouse, Tuskegee Institute, Alabama, 1942. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, FSA-OWI Collection, LC-USW3- 000185-D. Daniels chose not to describe his visit to Tuskegee in A Southerner Discovers the South, though he did recount what he learned there about racial violence in nearby Lowndes County. |

That Buck saw the book as only "moderately liberal" is worth pondering. His own Pulitzer prize-winning Road to Reunion, published in 1937, had celebrated sectional reconciliation after the Civil War while explicitly writing off black aspirations for citizenship rights and true freedom. As historian David Blight observes, "Buck sidestepped, or perhaps simply missed, the irony" of segregating African Americans out of the history and mythology of a reunited and supposedly democratic nation.63David W. Blight, Beyond the Battlefield: Race, Memory, and the American Civil War (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2002), 145. Although Daniels wrote more critically of blacks "sold down the river again after emancipation," his critique was not forceful enough to trouble the more conservative Buck.64Daniels, A Southerner Discovers the South, 345.

A number of reviewers understood Daniels' racial politics to be more progressive than Buck did — and certainly more progressive than they appear to modern readers. Benjamin Brawley in the Journal of Negro Education credited Daniels with suggesting "what some previous writers have failed to say, that before the South finishes solving her problems the Negro's political status will have to receive new consideration."65Brawley, "A Southerner's Travels at Home," 553. Yet Daniels had written nothing about black citizenship or voting rights. Similarly, Howard University law librarian A. Mercer Daniel praised Daniels in the Journal of Negro History as "a voice that rises above prejudice and speaks the truth."66A. Mercer Daniel, review of A Southerner Discovers the South in Journal of Negro History 24 (January 1939), 106. Daniels had expressed what fellow white southern liberal Virginius Dabney recognized (in his own patronizing tone) as a "firm faith in the ability of the Southern masses, both white and black, to march upward together."67Virginius Dabney, "Discovering the South," [Richmond Times-Dispatch?], clipping in A Southerner Discovers the South scrapbook, Daniels Papers, SHC. Daniels had written the frequently quoted lines that "The Southern Negro is not an incurably ignorant ape" and "The southern white masses are not biologically degenerate" — lines that Eleanor Roosevelt quoted proudly in one of two "My Day" columns in which she discussed the book.68Daniels, A Southerner Discovers the South, 343; Eleanor Roosevelt, "My Day," 28 August 1938, clipping in A Southerner Discovers the South scrapbook, Daniels Papers, SHC. Another "My Day" clipping in this scrapbook is dated 5 August 1938.

|

| William E. Leuchtenburg, ca. 1938, courtesy of William E. Leuchtenburg. |

Yet to say that Daniels rose above racial prejudice was to credit him only at his very best. "Alas, he was capable of writing of 'pot-bellied pickaninnies' playing in the Arkansas dirt, of 'Negresses black as licorice' in Mississippi, of 'gangling earth apes' on Beale Street," William Leuchtenburg laments in a 1996 reflection on the book, which he identified as one that changed his life. But in the context of the late 1930s, Leuchtenburg insists, "I also understand why he was regarded as one of the South's foremost liberal editors." The scene that stuck with Leuchtenburg then was not one in which Daniels betrayed his own racism but rather one in which he criticized the more vicious racism of another white southerner. This struck a chord because "as a provincial New Yorker with set notions of the ineradicable racism of Southern whites I was not expecting it."69Leuchtenburg in Books of Passage, 113-14.

|

| Photographer unknown, Sterling Brown, from the Sterling Brown Collection, Moorland-Springarn Research Center, Howard University. |

Among Daniels' contemporaries, black poet and essayist Sterling Brown offered a particularly insightful assessment of the book's mixed messages on race. Most of all, Brown appreciated Daniels' efforts to describe a more diverse and complex South than many previous authors. The book was "candid photography," a documentary "composite of the South, too long and foolishly called 'solid.'" It was also "valuable social commentary." Brown considered its travelogue format and casual, personal tone "deceptive." "Mr. Daniels knows how to disarm Southern prejudices," he argued. "A few sharp cracks at Yankee meddling occur here and there. But the South is taken severely to task; tabooed subjects are brought out in the open as when he mentions Virginia gentlemen 'breeding slaves for the Deep South,' or refuses to howl over Reconstruction, likening the Ku Klux Klan to the Brown Shirts of Germany and the Black Shirts of Italy" (a line that, surprisingly, was not frequently quoted in other reviews). Even though Daniels was "almost always fair-minded and sympathetic" towards African Americans, Brown felt his "chats with Negroes are too few."70Sterling A. Brown, "South on the Move," Opportunity, reprinted in John Edgar Tidwell and Mark A. Sanders, eds. Sterling A. Brown's A Negro Looks at the South (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 19-22. Tidwell and Sanders see Daniels' book as a major influence on Brown, whose published and unpublished writings about black life in the South they have collected in this volume.

As a man who had traveled extensively through the South himself and who, like Daniels, had come of age in the 1910s when the structures of Jim Crow were firmly in place, Brown understood why it was virtually impossible for even a sympathetic white to "chat" candidly with southern blacks. Unlike the white hitchhikers, gas station attendants, and waitresses whom Daniels routinely quizzed, the black southerners he happened to meet would have been unsettled, perhaps terrified, by probing questions from an unknown white man. Whether Daniels could have scheduled visits with local black leaders or scholars such as his SPC colleague Charles S. Johnson is a more challenging question. Other white liberals engaged in interracialism of various kinds, and some radical white southerners, such as the CIO and STFU organizers Daniels had met, were known for their efforts to work across race lines. Jonathan Daniels did not share this commitment.

Democracy is Bread

Daniels does seem to have shared some of Brown's sense that A Southerner Discovers the South was insufficient. In the fall of 1938, a few months after the book appeared, he published "Democracy is Bread" in the Virginia Quarterly Review. Here his tone was quite different. Opening with a description of himself talking with an economist and a "Harvard Yankee" labor organizer in an Atlanta hotel, he said the conversation became "serious because in Atlanta all of us saw, free this time of any circus trappings of klan, a cold-blooded and determined fascism in the South." The next morning, Daniels claimed, he woke up to read "that the South is Economic Problem No. 1. I am afraid it is more than that," he continued. "I fear — I hope foolishly — that not merely in its executive offices, but out on the gullied hills, something strange, too native to be [called] fascism, is breeding in the sun."

| Dorothea Lange, sharecropper family near Hazlehurst, Georgia, 1937. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, FSA-OWI Collection, LC-USF34- 017762-E. Farm Security Administration photographs and other documentary images accompanied some of the reviews of A Southerner Discovers the South, as well as Daniels's NEA articles. This image appeared alongside a review in the Richmond Times-Dispatch. |

Daniels praised New Deal policies in more clear-cut and specific terms than he had used in A Southerner Discovers the South, noting that "despite the [1937] recession, wages for labor are higher than they were before Roosevelt. Despite a widening after the collapse of the N. R. A. [the National Recovery Administration, declared unconstitutional in 1935], the wage differential between the North and South is less — often considerably less — than it used to be." Nonetheless, the masses of unemployed white southerners, most of whom had been displaced from agriculture, would continue to exert a fearful pressure on American politics. "In the South Huey Long and others have shown that these poor on their pathetic hills can be stirred," Daniels wrote. "And why should they not be? For millions of them democracy has failed to give the least that men may hope from government or from an economic order. And, of course, they can be stirred in false furies. Southern lynchings represent not merely degrading cruelty but a wild outlet for despair. Demagogues have led them against Negroes when what they wanted . . . was bread."71Jonathan Daniels, "Democracy is Bread," Virginia Quarterly Review 14 (Autumn 1938), 481, 482, 484, 489.

"Democracy is Bread" was a straightforward and critical analysis that drew the notice of President Roosevelt as well as southern newspaper editors. "Who is this Red who preaches such radicalism?" the Mobile Times asked tongue-in-cheek after summarizing the article. "He is none other than the author of the most talked-of book of the year, 'A Southerner Discovers the South.'"72"Democracy is Bread," Mobile (Ala.) Times, 7 October 1938, clipping in A Southerner Discovers the South scrapbook, Daniels Papers, SHC. Yet those who enjoyed A Southerner Discovers the South might have been surprised to read such a foreboding and politically focused essay. Daniels' central message was that the New Deal must be expanded. "This South may be, as the President says, Economic Problem No. 1," he concluded. "But National Problem No. 1 is to get down deep enough in democracy to make it serve where the hungry are. It will not be secure until that is done."73Daniels, "Democracy is Bread," 490.

The need for an expanded New Deal was also the message of three editorials Daniels wrote for the Newspaper Enterprise Association (NEA) Service in the fall of 1938. Perhaps because he anticipated a wider audience than that of the Virginia Quarterly Review, he returned in these syndicated columns both to safer political ground and to his more enigmatic tone. He began with folksy anecdotes presumably meant to disarm readers. He also diagnosed the problems of the South in clinical terms similar to those of the NEC's Report on Economic Conditions of the South, to which these articles were a response.74Jonathan Daniels, "Economic Problems of Blighted South Concern Every State, Writer Asserts,"Syracuse (N.Y.) Herald, 20 September 1938, p. 15. See also "More than Mere Statistics Involved in NEC Report on South's Poverty," Syracuse (N.Y.) Herald, 19 September 1938, p. 13. Syndicated by the NEA, these articles appeared under slightly different titles in a variety of newspapers around the country. Clippings of the NEA releases can be found in A Southerner Discovers the South scrapbook, Daniels Papers, SHC. Although these articles appeared less than a month before "Democracy is Bread," Daniels barely hinted at his fears of homegrown fascism or lynch mobs turned toward political targets. Instead, he tried to shock readers' sensibilities by arguing that there were "only two courses which non-Southerners in this America can take": they could help raise southerners' standard of living or they could "force independence upon the late Confederate states and lift high as heaven tariff and immigration walls." Yet even such barriers might not "withstand the pressure of Southerners looking for food," he warned, while the failure either to cut off or to aid the South would mean that Americans in other sections of the country must "bear the pull of the too-poor South downward on the standards of all. . . . every American everywhere will feel it on his job, on his wages, on his security."75Jonathan Daniels, "Bring South Up to Living Standards of Nation or Make It Independent Confederacy—Daniels," Burlington (N.C.) Daily Times-News, 22 September 1938, p. 21.

|

Despite this call for national aid, Daniels approached the subject of government planning in a gingerly way that had much to do with current events, specifically FDR's failed "purge." A few weeks earlier on August 11 (less than a week after Eleanor Roosevelt wrote in "My Day" that she and the President had been reading A Southerner Discovers the South aloud), FDR gave a speech in Barnesville, Georgia, in which he endorsed a more liberal candidate over incumbent senator Walter F. George, who was sitting behind him on the platform.76Eleanor Roosevelt, "My Day," 5 August 1938, clipping in A Southerner Discovers the South scrapbook, Daniels Papers, SHC. His "political interference" in this campaign and that of Senator "Cotton" Ed Smith of South Carolina "shocked many who are inclined to follow him," Birmingham editor John Temple Graves chastised.77John Temple Graves, "South is Critical of the NEC Report," New York Times, 21 August 1939, 58. Yet even if FDR could have somehow avoided stirring up southern resentment, his effort to push the southern Democratic Party in a more liberal direction was an uphill battle.

As Patricia Sullivan points out, "the poll tax and other restrictions kept most blacks and a majority of low-income whites from voting. This was the constituency of the New Deal, and the great majority of them did not participate in the 1938 primary elections."78Sullivan, Days of Hope, 66. Roosevelt's candidates lost the primaries, while Roosevelt himself lost not only supporters in the South but also his bid for a more favorable Congress that might support additional New Deal legislation.

"a very basic, vital ferment"

In this changing political climate, Jonathan Daniels' increasingly explicit calls for expanded federal aid and attention to the South amounted to very little. Even the Report on Economic Conditions of the South seems to have had almost no impact in Washington. As David Carlton and Peter Coclanis argue, Roosevelt's interest in the Report faded as soon as it became clear that the purge was destined to fail. "The major followup to the Report, then, would not be a slate of New Deal legislative proposals, but the encouragement of an insurgent movement" among progressive southerners.79Carlton and Coclanis, Confronting Southern Poverty, 27. Much has been written about the first meeting of the Southern Conference for Human Welfare (SCHW), a huge gathering of black and white southern liberals and some radicals in Birmingham in November 1938. Over 1,200 delegates attended and formed more than a dozen committees to respond to the Report and discuss such issues as education, voting rights, housing, unemployment, farm tenancy, and race relations. Although hindered by allegations of communism and other obstacles, the conference "would long be remembered," as John Egerton observes, "not for what it achieved, but for what it aspired to and what it attempted."80Egerton, Speak Now Against the Day, 197. On the Southern Conference for Human Welfare, see Thomas A. Krueger, And Promises to Keep: The Southern Conference for Human Welfare, 1938-1948(Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1967); Linda Reed, Simple Decency and Common Sense: The Southern Conference Movement, 1938-1963 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991); Carlton and Coclanis, Confronting Southern Poverty , 27-28; and Gilmore, Defying Dixie, 269-71. "Here was a ferment," founding SCHW member Arthur Raper remembered, "a very basic, vital ferment" that the South had long needed.81For Raper's comments, see Sullivan, Days of Hope, 67.

Yet even though SCHW president Frank Porter Graham attributed some of this ferment to A Southerner Discovers the South, Daniels chose not to attend the Birmingham meeting. When an Associated Press report made it seem that the SCHW had taken a stronger stand opposing segregation than it actually had, Daniels criticized the decision. The resolution was unwise, he insisted in a News and Observer editorial, because it "placed emphasis upon the one thing certain to angrily divide the South." It also seemed "to advocate a haste in the adjustment of racial relationships" that could be dangerous. For, "if progress is to be safe and sure, it must also be gradual." As in the Ericson affair in 1936, Daniels would soon find himself apologizing to a more liberal white southerner, SCHW executive secretary H. C. Nixon.82Eagles, Jonathan Daniels and Race Relations, 72-73 and see n. 52. But his apologies were private while his resistance to change was open to public view. Here again were the "contradictions of the culture" played out in Daniels' own consciousness. The man who could warn of a southern fascism that was growing in both "executive offices" and "gullied hills" could also push back against fellow progressives out of respect, not for segregation per se, but for the prejudices of other white southerners.

By 1938 Jonathan Daniels felt the South changing but was not sure how to react. He embraced his identity as "a Southerner" and responded to a friend's charge that he was "not a true Southerner," that he had "escaped," by saying, "I hope not. Escape is to the South, not away from it."83Daniels, A Southerner Discovers the South, 8. Nevertheless, by his definition of "Southerner," his father Josephus, who had led North Carolina's effort to disfranchise black voters, was "A Better Southerner," as he put it in his book's dedication, than he could ever be. A Southerner Discovers the South did take the South to task, as Sterling Brown discerned, but it did so obliquely because Daniels was ambivalent and because he wanted to avoid alienating white readers. His ability to disarm with anecdotes and "cracks at Yankee meddling" allowed his book to become the "non-fiction leader of the South" at precisely the same moment many white southerners were denouncing FDR's attempted purge.84"The Week's Best Sellers," Publishers Weekly, 3 September 1938, 768. Yet A Southerner's political influence was subtle at best. Like the documentary expressions of the period, Daniels' book exposed the South's problems to a broad general audience. But as Franklin Roosevelt learned after Barnesville, discovering the South hardly ensured the success of reform.

Recommended Resources

Caldwell, Erskine and Margaret Bourke-White.You Have Seen Their Faces. New York: Viking, 1937.

Carlton, David L. and Peter A. Coclanis, eds. Confronting Southern Poverty in the Great Depression: The Report on Economic Conditions of the South with Related Documents. Boston and New York: Bedford/St. Martin's, 1996.

Daniels, Jonathan. A Southerner Discovers the South. New York: Macmillan, 1938.

Denning, Michael. The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century. London, New York: Verso, 1996.

Dickstein, Morris. Dancing in the Dark: A Cultural History of the Great Depression. New York: Norton, 2009.

Eagles, Charles W. Jonathan Daniels and Race Relations: The Evolution of a Southern Liberal. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1982.

Egerton, John. Speak Now Against the Day: The Generation Before the Civil Rights Movement in the South. New York: Knopf, 1994.

Fleischhauer, Carl and Beverly W. Brannan, eds. Documenting America, 1935-1943. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988.

Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth. Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919-1950. New York: Norton, 2008.

Hall, Jacquelyn Dowd. "The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Political Uses of the Past," Journal of American History 91 (March 2005).

Puckett, John Rogers. Five Photo-Textual Documentaries from the Great Depression. Ann Arbor, Mich.: UMI Research Press, 1984.

Stott, William. Documentary Expression and Thirties America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973.

Sullivan, Patricia. Days of Hope: Race and Democracy in the New Deal Era. Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Links

http://docsouth.unc.edu/sohp/A-0313/menu.html.

Jonathan Daniels Papers, 1865-1982 at UNC'S Wilson Library

http://www.lib.unc.edu/mss/inv/d/Daniels,Jonathan.html.

| 1. | Jonathan Daniels to Josephus Daniels, 19 April 1937, in Folder 151 of the Jonathan Daniels Papers #3466, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Hereafter Daniels Papers, SHC. |

|---|---|

| 2. | "Notes Made on Southern Tour," p. 1, typescript in Folder 2089b, Daniels Papers, SHC. |

| 3. | Jonathan Daniels, A Southerner Discovers the South (New York: Macmillan, 1938). All references are to this edition. Publishers Weekly listed A Southerner Discovers the South among its "Candidates for the Best Seller List" in its July 30, August 6, and August 20, 1938, issues. The book then made the magazine's weekly and monthly best sellers lists for August and September. |

| 4. | For the book's popularity in the South, see "The Week's Best Sellers," Publishers Weekly, 3 September 1938, 768. Graham's view, expressed in a letter to Southern Policy Committee founder Francis Pickens Miller, is noted in Patricia Sullivan, Days of Hope: Race and Democracy in the New Deal Era (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 67. |

| 5. | Morris Dickstein, Dancing in the Dark: A Cultural History of the Great Depression (New York: Norton, 2009), 9-10. On the documentary tradition of the 1930s, see William Stott, Documentary Expression and Thirties America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973); John Rogers Puckett, Five Photo-Textual Documentaries from the Great Depression (Ann Arbor, Mich.: UMI Research Press, 1984); Carl Fleischhauer and Beverly W. Brannan, eds. Documenting America, 1935-1943 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988); Michael E. Staub, Voices of Persuasion: Politics of Representation in 1930s America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994); Michael Denning, The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century (London and New York: Verso, 1997), esp. 118-19; and Linda Gordon, Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits (New York: Norton, 2009). |

| 6. | Daniels left Fortune and returned to Raleigh in 1932, but not until after the November presidential election. See Jonathan Worth Daniels, interview by Charles Eagles, 9-11 March 1977, interview A-0313, Southern Oral History Program Collection (#4007), University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, available online in theDocumenting the American South Collection at http://docsouth.unc.edu/sohp/A-0313/menu.html. For Daniels' awareness of James Rorty's travels, see A Southerner Discovers the South, 86-87. |

| 7. | Daniels, A Southerner Discovers the South, 10. |

| 8. | "A Southerner Discovers the South," Avalanche-Journal, Lubbock, Texas, 17 July 1938, 21. |

| 9. | Lambert Davis, "Progress below the Potomac," Saturday Review of Literature, 16 July 1938, 5. |

| 10. | The July 12 publication date is mentioned in "Opportune Opus for Dixie," Richmond Times-Dispatch, 19 July 1938, clipping in A Southerner Discovers the South scrapbook, Folder OP-3466/24, Daniels Papers, SHC. On the leak of Roosevelt's letter, see David L. Carlton and Peter A. Coclanis, eds. Confronting Southern Poverty in the Great Depression: The Report on Economic Conditions of the South with Related Documents (Boston and New York: Bedford/St. Martin's, 1996), 19-20; and Steve Davis, "The South as 'The Nation's No. 1 Economic Problem': The NEC Report of 1938," Georgia Historical Quarterly 62 (Summer 1978), 122. |

| 11. | "Our 'No. 1 Problem,'" Boston Herald, 17 July 1938, 4, clipping in A Southerner Discovers the Southscrapbook, Daniels Papers, SHC; "Opportune Opus for Dixie," clipping, Daniels Papers, SHC; John Chamberlain, "Swing Around the South," The New Republic, 13 July 1938, 284. |

| 12. | Sullivan, Days of Hope, 6. |

| 13. | Quoted in Sullivan, Days of Hope, 67. |

| 14. | Carlton and Coclanis, Confronting Southern Poverty, 11. On the Southern Policy Committee, see also Francis Pickens Miller, Man from the Valley: Memoirs of a Twentieth-Century Virginian (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1971), 81-84; George Brown Tindall, The Emergence of the New South, 1913-1945(Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1967), 592-94; Bruce J. Schulman, From Cotton Belt to Sunbelt: Federal Policy, Economic Development, and the Transformation of the South, 1938-1980 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 40-43; and John Egerton, Speak Now Against the Day: The Generation Before the Civil Rights Movement in the South (New York: Knopf, 1994), 175-77. |