Overview

In 1884 the New York, Philadelphia, and Norfolk Railroad, a subsidiary of the powerful Pennsylvania system, extended its line south through the Eastern Shore of Virginia. For decades the Eastern Shore had remained disconnected from the rapidly advancing railroad network on the Atlantic coast, a region distinctly Southern in its cultural landscape and seemingly frozen in time. The arrival of the railroad altered the geography of the Eastern Shore in fundamental ways and prompted unforeseen changes in the peninsula's cultural and natural worlds. This essay examines what happened when one of the largest railroad companies in the nation came into a southern community and connected it to the modern network of rail and commerce. We consider the Eastern Shore a test case or laboratory for understanding the development of a modern landscape in the South and the social, cultural, and environmental changes that came with the railroad.

Introduction

|

| Map of Eastern Virginia, circa 1862 |

When in 1884 the New York, Philadelphia, and Norfolk Railroad, a subsidiary of the powerful Pennsylvania system, extended its line south through the Eastern Shore of Virginia, it had been anticipated for over forty years. The coming of the Pennsylvania system’s railroad to the Eastern Shore was catalytic. Combined with other technologies, cultural practices, speculative capital, and environmental changes, the railroad channeled development across the landscape. Its effects were predicted and unexpected, anticipated and far-reaching. One of the largest corporations in the United States, the Pennsylvania Railroad linked the remote peninsula to the largest cities in the East, accelerating changes in the landscape already underway on the Shore and spawning hosts of others.

Railroad cars carried Northward increasing quantities of Eastern Shore lumber, seafood, and farm produce and returned with all manner of raw, processed, and manufactured goods as well as with emigrants and tourists. A new infrastructure developed as towns grew up along the tracks, roads radiated from the towns, and eventually telephone and power lines followed the roads. Property values increased and population expanded. The emerging optimism of the people of the Eastern Shore found expression in the construction of wharves, warehouses, stores, houses, and public buildings; their growing sophistication in more frequent travel, the provision of better educational opportunities for their children, the adoption of up-to-date styles of architecture, the installation of indoor plumbing, and the purchase of automobiles, pianos, and other amenities. In general, the railroad and accompanying technologies made possible an enormous wealth in the countryside and brought sweeping changes in a remarkably short period of time. These changes produced drastic and far-reaching direct and indirect effects to the ecological systems of the Shore and, in turn, to its human residents.1An entirely new infrastructure around the railroad developed on the Eastern Shore in a tightly-compressed period of time, about twenty-five years. The railroad came late to the Eastern Shore. In contrast, Lincoln, Nebraska, had a railroad nearly two decades before the Eastern Shore of Virginia, despite the latter's proximity to the large cities of the east. Perhaps only the Texas Panhandle vied with the Eastern Shore in the 1880s for the distinction of remaining so long unconnected to the nation's rail network. See Tiffany Marie Haggard Fink, "The Forth Worth and Denver City Railway: Settlement, Development, and Decline on the Texas High Plains," (PhD Dissertation, Texas Tech University, 2004) for an analysis of town development that followed the railroad in the Panhandle.

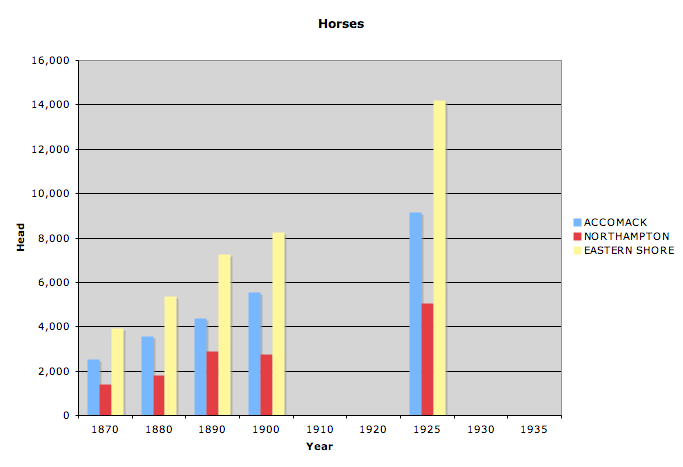

|

| Slideshow: Wilbur Zelinsky maps. Courtesy University of Iowa Press. |

What we seek to accomplish here is a close reading of the creation of a modern landscape to capture the interaction of technologies, people, and environment.2Computing digital technologies give us unprecedented capability to explore spatial relationships of the past in new ways. Through historical GIS and animation sequences, we hope to represent faithfully and accurately the development of this landscape, understanding the limits that the technology imposes. We have been guided in our idea of "landscape" and in ways of seeing the past by D. W. Meinig, ed. The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes: Geographical Essays. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979); especially Pierce F. Lewis, "Axioms for Reading the Landscape: Some Guides to the American Scene," and D. W. Meinig, "The Beholding Eye: Ten Versions of the Same Scene." We are interested here in the recent literature on regionalism, modernity, and human geography that stresses the "context" and "open multiplicity" in landscapes and the literature in crucial social theory that works to synthesize structural approaches with human agency. Of particular importance to this essay are the following works: J. Nicholas Entrikin, The Betweenness of Place: Towards a Geography of Modernity.( New York: Macmillan, 1991; esp. 27-59); Allan Pred, Making Histories and Constructing Human Geographies: The Local Transformation of Practice, Power Relations, and Consciousness. (Boulder: Westview Press, 1990; esp. 126-170); Anthony Giddens, Central Problems in Social Theory: Action, Structure and Contradiction in Social Analysis. (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1979) and The Consequences of Modernity. (Cambridge: Polity, 1990); Doreen Massey, Spatial Divisions of Labor, Social Structures, and the Geography of Production. (New York: Routledge, 1984); and Spaces, Place, and Gender. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995. The Eastern Shore of Virginia, according to geographer Wilbur Zelinsky in a pioneering essay "Where the South Begins," was situated along the border of a settlement landscape that marked the northern limit of the South. Zelinsky examined architectural styles, town characteristics, and countryside features to determine a pattern in what defined or marked the Southern landscape. He considered Virginia's Eastern Shore "decidedly Deep Southern." Its landscape, structures, and their spatial arrangements made the region more like Georgia or Tidewater Virginia than Pennsylvania or even its neighbors, Delaware and the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Other characteristics Zelinsky examined confirmed for him its place in the South: the lexical traits, the propensity to vote Democratic, the high proportion of African Americans, and the high ratio of mules to horses. Although he could not find "physiographic" reasons for the boundary, Zelinsky drew his northern limit of the South at the Maryland-Virginia state line on the Eastern Shore, "an emphatic interstate and cultural boundary [that] match beautifully for unknown reasons."3Zelinksy, Wilbur. "Where the South Begins: The Northern Limit of the Cis-Appalachian South in Terms of Settlement Landscape," in Exploring the Beloved Country: Geographic Forays into American Society and Culture (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1994), 186, originally published in Social Forces 30 (1951), 172-178. D. Western identifies common characteristics of human-modified ecosystems, many of which apply to Eastern Shore Virginia between 1880 and 1920 (and ongoing), including: (1) high natural resource extraction (e.g., harvesting and exporting nutrients in produce), (2) habitat homogeneity (e.g., tightly managing forested lands), (3) landscape homogeneity (e.g., conversion to cropland), (4) large importation of nutrient supplements (e.g., fertilizers), and (5) global mobility of people, goods, and services (e.g., linking local resources and interests to national markets). D. Western, "Human-modified ecosystems and future evolution," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98 (2001), 5458-5465.

|

| Eastern Shore Map, area highlighted. |

Although recognizably Southern in its settlement landscape, the Eastern Shore of Virginia during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, was a highly complex and interdependent landscape. It was a liminal place, a zone of interpenetration, where the settlement patterns, speech, demography, and political outcomes defined its place in the South but its engagement with technology and rapid transformation of the landscape betrayed other allegiances, motives, forces, and effects. In this zone where the South "ends," we can understand more about the region's modern development because the contradictions at the heart of it stand in such stark relief.

Modernity came to the Eastern Shore of Virginia, as it did elsewhere in the South, in the form of a radical shift in the use of resources and labor relations, and in a transformation of the landscape.4The term "modernity" has been variously defined. Here, we mean social, technological, and economic changes that opened localities to fast, far-reaching, integrated communication and transportation. Our concern is with this process of transformation on the Eastern Shore and to understand the varied contexts for this process even in a relatively small, but environmentally-complex area. See especially Anthony Giddens, The Consequences of Modernity. (Cambridge: Polity, 1990, 18-19). The relationship between the railroad, market integration, and the environment, moreover, stood at the heart of their modernizing landscape: the reach of markets for both buying and selling nearly everything produced in the world, the expanding and tightening of worldwide communication, the fundamental alteration of widely-held conceptions of space and time, and the visible and invisible reconfigurations of the region's natural system. But there was no simple correlation among these components. Eastern Shore residents had long felt the effects of the market, participated in Atlantic trading, and maintained long-standing shipping practices with major urban centers in the Eastern United States. They responded to the changing market conditions even before the railroad reached the peninsula. Indeed, the railroad's penetration elsewhere, especially its linking of the Midwest with the major urban centers in the mid-Atlantic, had substantial repercussions along the Shore, as it brought new competition to established markets.5The concept of "transformation" in the countryside is one that William Cronon pioneered in Nature's Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. Rather than seeing the Shore as an outpost brought into the orbit of a major city for its natural resource advantages, we see instead a process that was directed both from within the region and without and that reconfigured the physical landscape, obliterated old commercial hierarchies, and spawned sweeping environmental changes. William Cronon, Nature's Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (New York: W. W. Norton, 1991). See also Cronon's "Modes of Prophecy and Production: Placing Nature in History," Journal of American History, 76, no. 4 (March 1990), 1122-1131. Cronon calls for greater specificity in defining stability and instability; not all capitalist or modern forces can be considered destabilizing and not all traditional forces stabilizing. Market integration, and the railroad's role in it, has been a longstanding debate in Southern history. See Steven Hahn, The Roots of Southern Populism: Yeoman Farmers and the Transformation of the Georgia Upcountry, 1850-1890 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985) for an interpretation that stresses the shift from self-sustaining agriculture to dependency and monoculture in the upcountry cotton regions. See also, Steven Hahn and Jonathan Prude, ed., The Countryside in the Age of Capitalist Transformation: Essays in the Social History of Rural America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985).

The arrival of the railroad, though, marked an important moment.6For another recent work of regional study in which the railroad's arrival figures prominently, see Benjamin Heber Johnson, Revolution in Texas: How a Forgotten Rebellion and its Bloody Suppression Turned Mexicans into Americans (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 27-37. For Johnson the railroad penetrated the isolated region along the Texas-Mexico border and disrupted the "distinctive racial order" bringing with it segregation and drastic changes in the labor and land markets that were disastrous for Tejanos. It altered the geography of the Eastern Shore in fundamental ways and prompted unforeseen changes in the cultural and natural worlds of its residents. The Pennsylvania Railroad, the federal and state governments, alliances of local residents, and outsiders all acted upon the Shore's natural and human resources. Each extended networks across the landscape; each wanted to expose or exploit the landscape, nature, and human connections; and each confronted limits to its vision. On the geologically-stable mainland, the myriad changes in the landscape (themselves intrinsically limited by nature) held steady for decades and became organized around new crops and markets that propelled the Eastern Shore for a time into the front ranks of agricultural success stories in the United States. The confluence of forces and energies, moreover, that sustained the enormous success of the region, did not last, and, ironically, the vestiges of this transformation dominate the landscape of the Shore today. Along the chain of ever-shifting barrier islands shielding the peninsula from the Atlantic Ocean, alterations in the landscape proved far less enduring. Human activity on the islands was one of advance and retreat before the forces of tide, current, and storm.7On high modernist ideology and how governmental institutions have tried to "see" the landscape and its residents, see James C. Scott's innovative and excellent study Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998). Contemporary science stresses the complex and interdependent character of human and natural systems. Technological advances and economic forces are recognized as principal factors driving modern environmental change (see, for example, Veldkamp and Fresco, "CLUE: A Conceptual Model to Study the Conversion of Land Use and its Effects," Ecological Modelling, 85 (1996), 253-270). The "new ecology" focuses on "people in places" as a way of framing the environment as both the setting and the product of human activities (see, for example, Scoones, "New Ecology and the Social Science," Annual Review of Anthropology, 28 (1999), 479-507; and the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment www.millenniumassessment.org sponsored by the United Nations.

On the Edge of Modernity

Introduction

|

| Reference Map of the Eastern Shore. |

The Eastern Shore of Virginia is geographically removed from the rest of Virginia. It extends south from the Pocomoke River, which separates it from the Eastern Shore of Maryland, to form the southern tip of the Delmarva Peninsula and sits between the largest estuary in the United States, the Chesapeake Bay, to the west, and the Atlantic Ocean, to the east. The Eastern Shore counties of Accomack and Northampton encompass approximately 480 square miles of surface area, which can be characterized as a peninsular mainland penetrated by bayside tidal creeks and buffered from the ocean by a string of low barrier islands and associated marshlands. Mainland terrain ranges in elevation from sea level to about sixty feet and runs approximately seventy miles from the southern tip of the peninsula at Cape Charles to the Maryland border to the north. Maximum width including the marshes and barrier islands is approximately fourteen miles.8The Role of Agriculture-Agribusiness in the Economic Development of Virginia's Eastern Shore (Blacksburg: Virginia Polytechnic and State University, 1971), 2, correctly divides the Eastern Shore into three main physiographic divisions: (1) the Mainland, (2) the Coastal Islands, and (3) the Marshes. The Mainland contains practically all cultivable, productive soils of the region; the Coastal Islands, low and sandy, occur as a chain along the Atlantic Ocean; and the Marshes are present in extensive tracts on both sides of the peninsula.

The Geophysical Landscape

The geophysical backdrop of the Eastern Shore of Virginia is predominantly one of change, both on long- and short-term scales. The current mainland-marsh-lagoon-barrier island complex has its origins in the sea level rise at the end of the last Ice Age (about 15,000 years ago), which released water from the polar ice cap and eventually inundated the Susquehanna River Valley. The melting slowed about 3,000 years ago, at which time the Chesapeake Bay took its current form.9Discovering the Chesapeake: The History of an Ecosystem, eds. Philip D. Curtin, Grace S. Brush, and George W. Fisher (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001) argues convincingly that the basic geography of the Eastern Shore was established about 2,000 to 4,000 years ago when sea level rise slowed after the end of the last Ice Age.

The pace of sea level rise began to increase around 1850 and yet again around 1920 until it approximated its current rate of about 0.14 inches per year at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay. Given the low relief on the Eastern Shore (although the highest point on the peninsula reaches an elevation over fifty feet above sea level, barrier islands average only about seven feet above sea level), these changes in sea level resulted in significant geomorphic alteration to low elevation marshes and barrier islands that buffer the mainland from the Atlantic Ocean. For example, marshlands declined 16 per cent between 1852 to 1960 due largely to sea level rise. Moreover, between 1872 and 1910 the south end of Hog Island eroded landward (to the west) while the north end eroded seaward (to the east), eventually leading to the submergence of the village of Broadwater, which today lies more than a mile out into the Atlantic Ocean.10The Virginia Coast Reserve Long Term Ecological Research station has been funded by the National Science Foundation for the past 19 years to study the mosaic of transitions and steady-state systems that comprise the barrier-island/lagoon/mainland landscape of the Eastern Shore (see http://www.vcrlter.virginia.edu/). The fourteen coastal barrier islands of Eastern Shore Virginia, with their associated beaches, intervening inlets, marsh islands, mud flats, salt marshes, shallow bays and channels, are the only undeveloped barrier system on the eastern seaboard. For an explanation of sea level-marsh-barrier island dynamics, see J. Stevenson. and M. Kearney, "Shoreline Dynamics on the Windward and Leeward Shores of a Large Temperate Estuary," in Estuarine Shores: Evolution, Environments and Human Alterations (John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 1996); For a broad overview of environmental change on the Eastern Shore, see B. P. Hayden and J. Hayden, "The Land Must Change to Stay the Same," and P. Holleran "Islands on the Go," Virginia Explorer (Fall, 1994).

| Slideshow: Hurricane Paths, Eastern Shore and Vicinity, 1872-1928 |

In 1870 the Eastern Shore's level terrain comprised a patchwork of fields and woods penetrated by sinuous tidal creeks. The woods were predominantly loblolly pine (travelers often remarked on their "pungent odors") but also included shortleaf pine and hardwoods such as oak, hickory, and sycamore. The soils of Accomack and Northampton, mostly light, sandy loams, were well drained, easily cultivated, and receptive to the application of fertilizer. "Cultivation is exceedingly cheap," an agricultural expert reported, "as a one-horse plough is sufficient generally, and a horse requires no shoeing, and vehicles and farm utensils will last double as long as in the mountain regions. For 'trucking' purposes, it is unsurpassed." Another authority deemed the soils of Accomack and Northampton "among the most productive . . . of the Atlantic Coastal Plain." The Eastern Shore also enjoyed the agricultural advantages of a mild climate, abundant rainfall, and a long growing season.11E. H. Stevens, Soil Survey of Accomac and Northampton Counties, Virginia (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1920), 6-7, 9, 10, 12, 23, 36, 59, 60 (third quotation); "The Eastern Shore," New York Evening Post, April 25, 1885; "Our Peninsula," Wilmington Morning News in Accomac Court House Peninsula Enterprise (hereafter cited as PE), November 22, 1884 (first quotation); Orris A. Browne, "The Eastern Shore", American Agriculturist in PE, April 11, 1885; ); A Handbook of Virginia (Richmond: Superintendent of Public Printing, 1879) (second quotation).

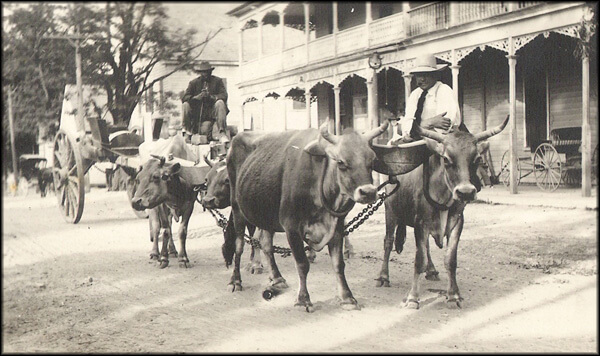

Because the mainland was so narrow — averaging six to eight miles wide — no locality was remote from a wharf or landing or, after the coming of the railroad, a depot. Some of its bayside creeks and seaside inlets were deep enough to admit steamboats and all accommodated small sailing craft such as schooners and sloops. In 1880 the Eastern Shore customs district registered 358 sailing vessels, the largest registration of Virginia's seven districts. The navigation of the waterways depended on knowledge and skill. A few longstanding structures, such as house chimneys, served mariners as guideposts.12Stevens, Soil Survey, 5, 9; Annual Statements of the Chief of the Bureau of Statistics on the Commerce and Navigation of the United States, June 30, 1880 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880), 847.

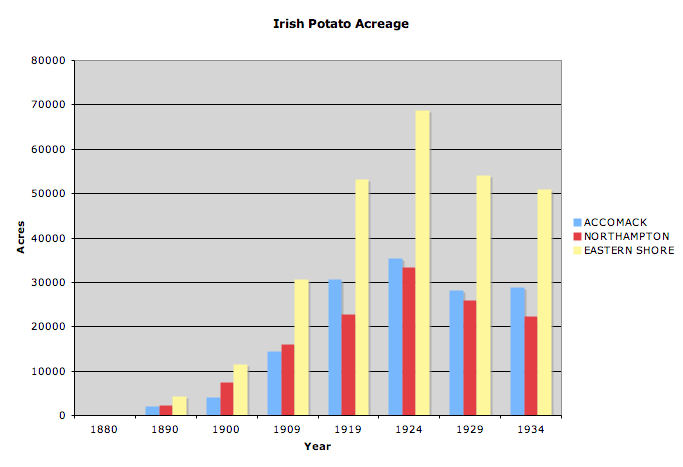

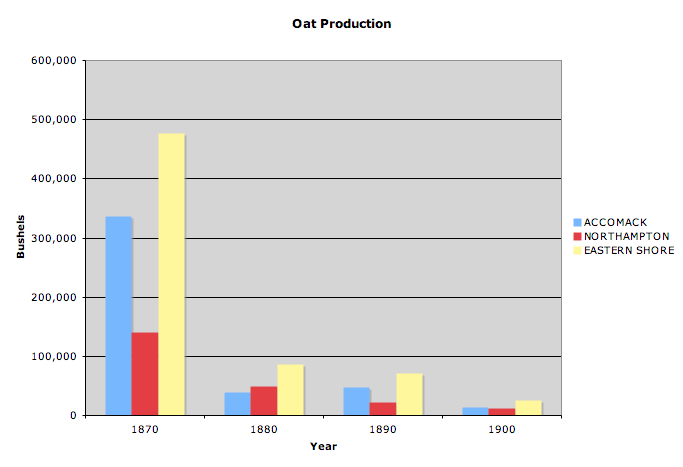

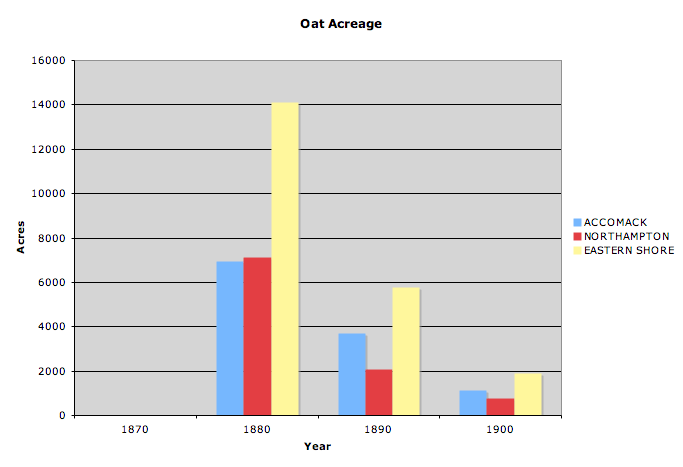

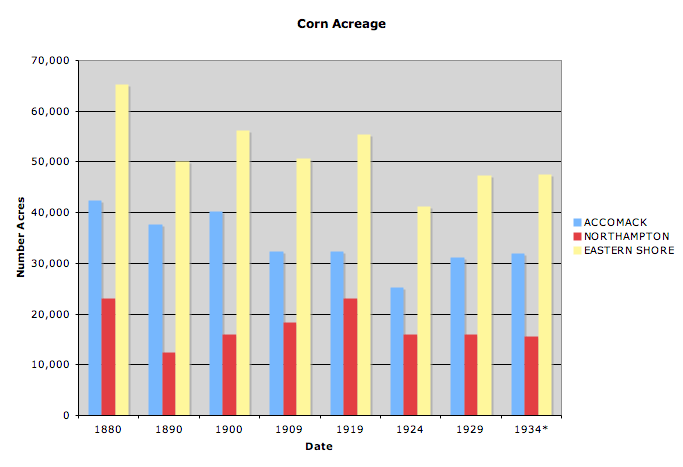

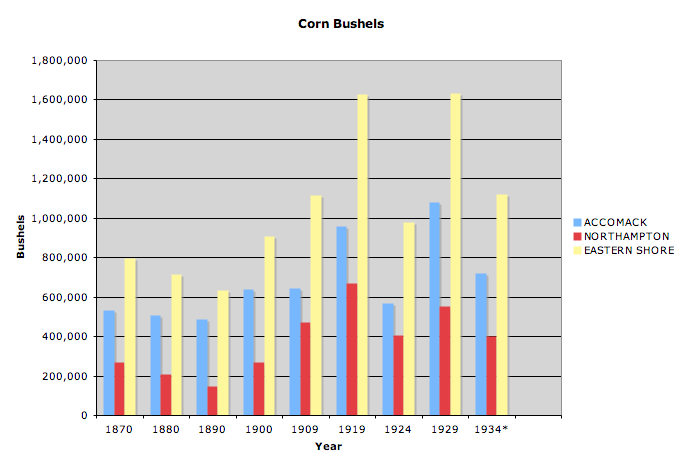

The great majority of the peninsula's 28,455 people (12,690 of whom were black) made their living from the land. Their farms averaged 128.5 acres and were seated close to waterside landings and wharves. Eastern Shoremen were commercial farmers, having long participated in the commerce of the Atlantic coast. For generations their cash crops had been corn and, recently of more importance, oats. "We eat our own grain, and drink our own grain, and sleep upon our grain," a Northampton man had remarked in 1824. By the 1870s, Eastern Shore farmers found their oats undersold in their principal markets — Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, and Boston — by those of the immense bonanza farms of the Midwest.By the 1890s, moreover, Midwestern economies of scale and the efficiency of the national transportation network insured that corn imported to Chincoteague Island from New York would undersell that grown on the adjacent mainland. Eastern Shore farmers responded to the new competition by gradually shifting over the 1870s and 1880s to the production of sweet and white potatoes.13The Statistics of the Population of the United States . . . Compiled from the Original Returns of the Ninth Census (June 1, 1870) (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1872), 637; The Statistics of the Wealth and Industry of the United States . . . Compiled from the Original Returns of the Ninth Census (June 1, 1870) (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1872), 266, 270; Stevens, Soil Survey, 16-17; Claude H. Hall, Abel Parker Upshur: Conservative Virginian (Madison: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1965), 28 (quotes Upshur); Barbara Jeanne Fields, Slavery and Freedom on the Middle Ground: Maryland During the Nineteenth Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985), 170. For antebellum Eastern Shore agriculture see "Sketch of a Hasty View of the Soil and Agriculture of the County of Northampton," Farmers' Register 3 (1835), 233-240 and "Quantity and Value of the Exports of the County of Accomac," Ibid. 8 (1840), 255.

The Eastern Shore was overwhelmingly rural. Only Chincoteague, locus of the Chincoteague Bay oyster industry, and Onancock, where granaries lined the north branch of Onancock Creek, were worthy to be called towns. A few villages stood at wharves, at crossroads, and at the heads of creeks. In 1883 a traveler found at the crossroad hamlet of Temperanceville in upper Accomack County "two stores, steam saw, flour and grist mills, a smith’s shop, postoffice, etc. and about a dozen scattered dwellings."14"Onancock and Accomack County," Richmond Times-Dispatch in Onancock Accomack News (hereafter cited as AN), October 30, 1909; "The Eastern Shore," Richmond State, July 24, 1883 (quotation).

Land and Sea

The Abstract Landscape: Pyle's "Peninsular Canaan"

In May 1879, Howard Pyle, a young writer and illustrator and a keen observer, headed down to the Eastern Shore of Virginia to write a story for Harper's New Monthly Magazine. Born in 1853 and raised in Wilmington, Delaware, Pyle admired the realistic writing of William Dean Howells. Pyle set out to capture the daily life and record what he considered the feel and experience of the landscape on the Eastern Shore. Pyle described the shore as "a peninsular Canaan," a place of almost unbelievable fertility where "the lightest labor" brings forth "abundant return from this generous soil." The waters "teem" with all manner of wildlife: fowl, terrapin, snipe, fish, and the prized Chesapeake oyster. Separated from the rest of Virginia by the broad waters of the Chesapeake Bay, the Eastern Shore remained remote. "There is no railroad," Pyle explained. The peninsula was separated from the "vim and progress of modern utilitarianism," an island, as it were, cut off from "the outside world."15Howard Pyle, "A Peninsular Canaan," Harper's New Monthly Magazine 58 (May, 1879), 801-817. On Pyle, see Lucien L. Agosta, Howard Pyle (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1987), and Elizabeth Nesbitt, Howard Pyle (London: The Bodley Head, 1966).

For all of its rich bounty and stark beauty, the Eastern Shore was, according to Pyle, stuck in "a Rip Van Winkle sleep." It was a place where all that nature provided seemed to go unrealized and where modernity remained unclaimed. It was "sleepily floating in the indolent sea of the past, incapable of crossing the gulf which separates it from outside modern life."

Like many Americans of his day, Pyle saw the landscape as an expression of a human society and modernity as a geographic, as well as a social and economic system. In the case of the Eastern Shore, the landscape was in large part the product of an earlier time, the plantation South. Pyle saw vestiges of it everywhere he looked. The first signpost of an older order was a collection of old windmills in Northampton County. These were "landmarks of the past," "quaint," "abandoned," and representative of an outrageously outdated technology and society. Another "remnant" Pyle recorded was the "Negro burying ground." Although slavery was "a bygone thing," Pyle noted, its presence in the landscape was literally still visible in unruly clumps of trees that farmers ploughed carefully around. These copses marked the final resting place, Pyle explained without irony, of "the planter's former faithful servants."16

T. Abel and J. R. Stepp, "A New Ecosystems Ecology For Anthropology," Conservation Ecology 7 (2003), 12, and S. R. Cooper, "Chesapeake Bay Watershed Historical Land Use: Impact On Water Quality And Diatom Communities," Ecological Applications, 5 (1995), 703-723, are indicative of contemporary agreement of the generalization that "the landscape was in large part the product of an earlier time."

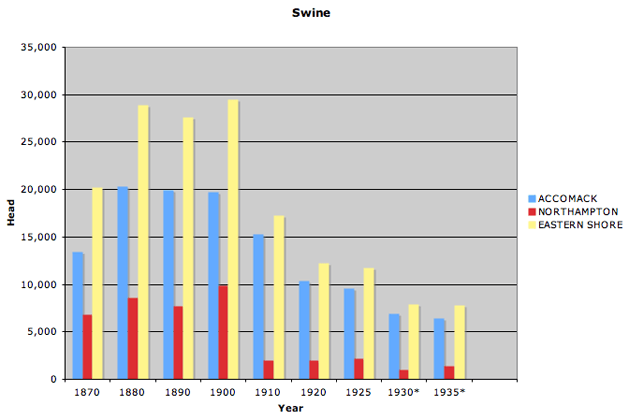

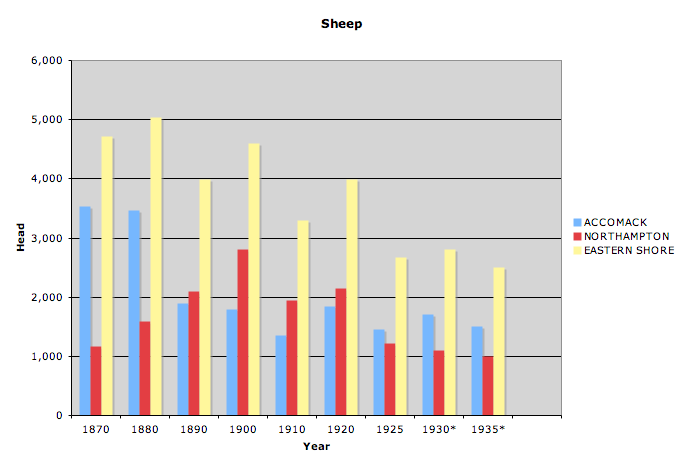

Pyle told his readers that the "remnant" of the Southern past remained deeply embedded in the landscape of the Eastern Shore where "the old style farming" was still practiced. "There were only three crops raised in Virginia," Pyle deadpanned, "corn, hogs, and niggers, of which the hogs ate all the corn, and the niggers devoured all the hogs. One of these 'crops,' however, is removed from the list." Pyle's comments, delivered with a wink-of-the-eye to his mostly Northern readers, were meant to buttress the Northern understanding of slavery and its landscape as hopelessly inefficient, a sort of shell game in which the players long ago lost track of the nut. The resulting legacy was, according to Pyle, an impoverished white class, "woefully ignorant," and an unproductive upper class, "indolently unprogressive."

Pyle saw only one way to bring the natural fruits of the soil and sea to full development and to establish a correspondingly modern social structure on the Eastern Shore: change the landscape. The coming of the railroad, he expected, would inaugurate sweeping changes in social arrangements and physical properties. Poor whites and indolent upper classes, not to mention blacks, would only disappear from the social landscape when the geography of modern America penetrated the region. A few years earlier Pyle had taken an excursion to Chincoteague to report on the local society and the annual roundup of the wild ponies on the barrier island. He described the ferry ride from the mainland across Chincoteague Bay for the prospective traveler: it "separates him from modern civilization, its rattling, dusty cars, its hurly-burly of business, its clatter and smoke of mills and factories, and lands him upon an enchanted island, cut loose from modern progress and left drifting some seventy-five years backward in the ocean of time. No smoke of manufactories pollutes the air of Chincoteague; no hissing steam escape is heard except that of the [steamboat] 'Alice;' no troublesome thought of politics, no religious dissension, no jealousy of other places, disturbs the minds of the Chincoteaguers, engrossed with whisky, their ponies, and themselves."17Howard Pyle, "Chincoteague: The Island of Ponies," Scribner's Monthly Magazine XIII (April, 1877), 737-745.

Pyle was not alone in his perception of the landscape of the South and its holdover social structures, nor was his understanding of the landscape and the railroad's possibilities novel. For Pyle in the 1870s the Eastern Shore and the rest of the South were part Arcadia, part wolf pit. Nineteenth-century Americans had long associated the use of and control over nature with enlightenment and civilization. Travelers to the South before the Civil War, among them Frederick Law Olmstead, observed land use patterns as inefficient. They focused their attention on the unimproved acreage, abandoned lands, and wild growth that consumed the typical farms. In his A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States with Remarks on their Economy published in 1857, Olmstead admitted to being a "fault finder." And although his travels opened with a visit to a well-kept Maryland farm, Olmstead's train ride south revealed an abandoned, apparently unproductive landscape "grown over with briars and bushes, and a long, coarse grass of no value."18 Frederick Law Olmstead, A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States with Remarks on their Economy (Samson Low and Son: London, 1857), 17.

Olmstead, Pyle, and other travel writers tied the landscape of the South to the character of its inhabitants; the land was, after all, a product of human intentions. Pyle remained decidedly Victorian in outlook, ironically detached from the transformations underway around him. His stereotypical account was meant more to titillate Northern readers with a close-to-home adventure story than to describe accurately the society and landscape he entered. Yet for all his nostalgia, Pyle observed the landscape of the Shore before the great layers of intervention between 1870 and 1900 had been completed or their complex repercussions felt, and he accurately sensed the magnitude of impending change.

The Railroad and the Modern Landscape

Introduction

|

| Slideshow: Expansion of the Pennsylvania Railroad, 1851-1893. |

Layers of modern infrastructure came in waves upon the Eastern Shore, altering its landscape in a remarkably short time. The key catalysts to the Eastern Shore's landscape included: first, the intense mapping of the coastlines in the US Coast Surveys of 1870-71, then the expansion of the US Post Office and the US Life-Saving Service, the development of the railroad in 1884, the River and Harbor Acts in the 1890s, and the creation of the Eastern Shore Produce Exchange in 1900. Each provided both extensive and intensive networking, while contributing to a substantial intervention in the physical landscape and an equally substantial one in the abstract landscape.

By the 1890s the effects of these layers were more clearly visible. Thomas Dixon, the prominent writer and Klan novelist, lived for several years in the mid-1890s in Cape Charles City, a bustling new town created around the railroad in lower Northampton County, but, like Pyle, he wished to ignore the activity of wharf and depot and their connections with the outside world. An avid outdoorsman, Dixon loved the barrier islands and the Broadwater, the expanse of marshes, bays, and channels that lay between the islands and the mainland. He hunted the Broadwater's waterfowl and shorebirds, dined on its oysters, and stood in the solitude of its vast marshes. "How far away the land world seems now," Dixon recalled of his trips out into the waters offshore, "fifteen miles from a post-office, telegraph line, or a railroad. We never see a newspaper, know nothing of what is going on in the big, steaming, festering cities and have ceased to care to know. Our world is now a beautiful bay, fed from the sea by two pulsing tides a day." Here, Dixon found "a world without railroad or mail." These symbols of modernity seemed corrupting to Dixon, but he deceived himself in dreaming of the Broadwater as a place where they had not yet reached. After all, the railroad had brought Dixon to Cape Charles City and mail boats traveled regularly from the mainland to post offices on Cobb’s, Hog, and Chincoteague islands.19Thomas Dixon, Jr., The Life Worth Living: A Personal Experience (New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1905). Record of Appointment of Postmasters, 1832-September 30, 1871, Microfilm Publication M841 (Washington: National Archives, 1973).

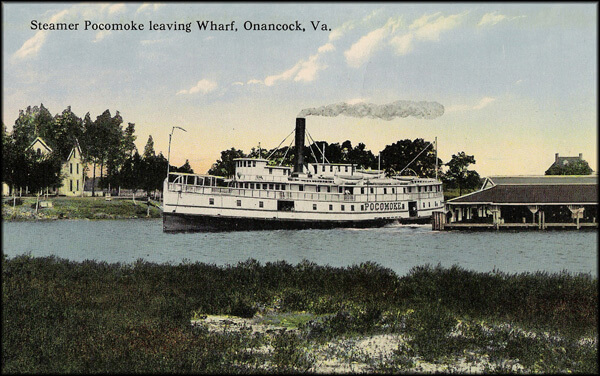

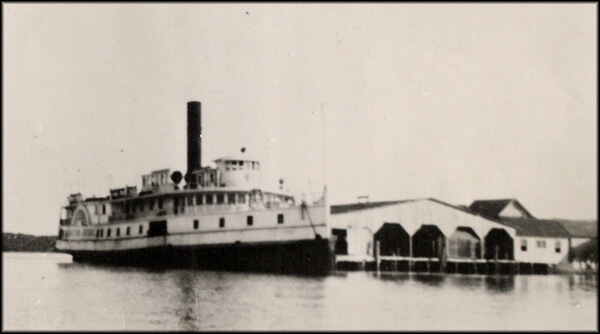

What Dixon cherished about the Shore was its deeply Southern cultural landscape that possibly obscured for him the rapid change all over the region. Dixon appreciated the hunting lodges and the shooting and yachting life in part because it echoed the plantation era's racial and class hierarchy. Here, he could survey the great marshes from a duck boat poled by a black man and feast on large dinners prepared and served by black hands. Dixon could be taken back in time, or at least stop time, by moving away from the railroads, the mail, and onto the Broadwater. His associates in these lodges were similarly inclined, and the Eastern Shore of Virginia, whatever its transitions and modern developments, was to them the closest piece of the Old South to New York City.20The plantation analogy should not be pushed too far. Both blacks and whites worked as guides and cooks, and out on the labyrinthian Broadwater even the wealthiest sportsman soon learned that the guide was master. For a recent assessment of Dixon, see Michele K. Gillespie and Randal L. Hall, Thomas Dixon Jr. and the Birth of Modern America (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006), especially Fitzhugh Brundage's assessment that Dixon was eager to use the technology of the day, especially film and railroads (29-30). The railroad's arrival on the Eastern Shore, however, offered a moment of particular consequence for the region.21Historians of the South, as well as of the United States generally, have long determined that the railroads were widely significant and nearly every history of the region deals with railroads. For critical works that examine the railroads in the South, see Edward L. Ayers, The Promise of the New South: Life After ReconstructionHistory of The Louisville and Nashville Railroad (New York: MacMillan, 1972), William G. Thomas, III, Lawyering for the Railroad: Business, Law, and Power in the New South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1999), Kenneth Noe, Southwest Virginia's Railroad: Modernization and the Sectional Crisis (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994), Allen Trelease, The North Carolina Railroad, 1849-1871, and the Modernization of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), and the classic John F. Stover, History of the Railroads of the South, 1865-1900: A Study in Finance and Control (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1955). There has not been a recent scholarly treatment of the Pennsylvania Railroad's history, see George H. Burgess, Centennial History of the Pennsylvania Railroad, 1846-1946 (Pennsylvania Railroad Co., 1949). See also, Richard T. Wallis, The Pennsylvania Railroad at Bay: William Riley McKeen and the Terre Haute & Indianapolis Railroad (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001). If the pattern of railroad development in the United States was, according to Wolfgang Schivelbusch, first and foremost to extend water navigation and open these territories to markets, then on the Eastern Shore it proceeded instead in direct competition with water transportation.22Wolfgang Schivelbusch, The Railway Journey: Industrialization and Perception of Time and Space (University of California Press, 1987). "The American railroad's original and fundamental task was to create transportation where no natural waterways existed" (111). If American railroads had been built generally with curves to engineer their way around obstacles and connect towns, the Eastern Shore line hewed like a broken compass needle to the spine of the peninsula, avoiding even the slightest curve. It was designed by the Pennsylvania Railroad to connect Philadelphia with the Deep South via Norfolk and to compete with steamboat companies for the freight. It bypassed every major town on the Eastern Shore, created its own private harbor and facilities, and developed no towns along its line. It was not meant to serve local interests at all, but the railroad's acceleration of time and reconfiguration of space had profound effects on the Eastern Shore's water-dominated landscape. However much the author Thomas Dixon might consider the Eastern Shore his own private "Peninsular Canaan," many of the local residents grasped the significance of the opportunities that the railroad made possible. They eagerly fashioned a remarkable new landscape around them, one that would last for generations.

Mapping the Waters — the US Coast Survey

No one could travel across the Eastern Shore without crossing water, and for generations most places were reached only by boat. The traffic moved up creeks to well-established public and private wharves, across the broadwater to the barrier islands, and out into Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. Beginning in 1870, the United States Coast Survey (USCS) mapped in detail the seacoast of the Eastern Shore of Virginia. These surveys indicated marshes, channels, inlets, bars, islands, and soundings. They located lighthouses, buoys, markers, and other navigational aids. For the first time they formalized and opened to the public information for navigating the complex seascape of the region and provided comprehensive data for future navigational aids and instruments. For decades the War Department controlled seacoast mapping for military purposes, and the Civil War accelerated modern seacoast mapping along the Virginia Capes. In the 1870s the pace of USCS work intensified and took on a scientific and exploratory character. The activities of the USCS teams were followed with close scrutiny on the Eastern Shore. The USCS hired local residents to help survey — what a newspaper editor termed "mapping out our waters."23PE, September 10, 1887, April 30, 1887, and October 15, 1887. The USCS had undertaken a less intensive mapping of the Eastern Shore coastline in the 1850s.

Taking full advantage of the newly-documented information on the Shore and its complex waterways, private steamboat companies improved old networks of communication and established new ones. Immediately after the Civil War, steamboat companies out of Baltimore and Norfolk increased the number of vessels and wharves on their Eastern Shore lines. By the early 1880s, steamers called regularly at twenty-three wharves on the bayside of the peninsula and during the potato harvest at eight on the seaside. Baltimore dominated the bayside trade of Accomack and upper Northampton, while Norfolk captured that of lower Northampton. On the seaside the trade networks were also divided. From there, steamers out of several Atlantic coast ports carried produce to Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. Position, proximity, access, and history combined to divide the tiny Eastern Shore into numerous zones of trade and traffic.24A. Hughlett Mason, History of Steam Navigation to the Eastern Shore of Virginia (Richmond: Dietz Press, 1973), 1, 12; Brooks Miles Barnes, "Triumph of the New South: Independent Movements in Post-Reconstruction Politics," PhD Dissertation, University of Virginia, 1991, 14; John R. Waddy to William Mahone, January 23, 1882, William Mahone Papers, Manuscript Department, William R. Perkins Library, Duke University.

Postal Service

|

| Expansion of Post Offices along the Eastern Shore from 1793-1917. |

At the same time, post offices expanded their reach and operation. The post office network was more uniformly managed and provided in the early 1880s a powerful enhancement of the Eastern Shore’s reach into the modern markets of information, commerce, and capital as well as a reconceptualization of space and time. Patronage politics combined with the coming of the railroad, quickening commerce, and a growing population to expand dramatically postal service on the peninsula. Between 1881 and 1884 the importunities of US Senator William Mahone persuaded the administrations of Republican presidents James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur to increase from forty-four to sixty-seven the number of post offices in Accomack and Northampton counties. The advent of the railroad in 1884 further stimulated the establishment of post offices both along the tracks and out in the countryside. By 1917, the number of post offices in the two counties had climbed to eighty-eight.25Barnes, "Triumph of the New South," 213; Stevens Soil Survey, 12. On the concept of "reach" and for an excellent overview of the history of the Gilded Age, see Edwards, New Spirits. See chapter 2, especially p. 55 on the postal service, as well as p. 19 for the LSS. For the effect of the railroad on postal service see G. Terry Sharrer, A Kind of Fate: Agricultural Change in Virginia, 1861-1920 (Ames: Iowa State University Press, 2000), 92. See Richard John, Spreading the News: The American Postal Service and Distorder in American History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995). Rural free delivery, which began on the Eastern Shore in 1905, eventually reduced the number of post offices (James Egbert Mears, "The Eastern Shore of Virginia in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries" in The Eastern Shore of Maryland and Virginia, ed. Charles B. Clark (New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1950), II, 596.)

|

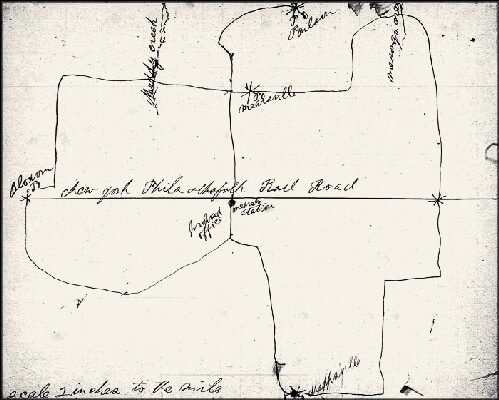

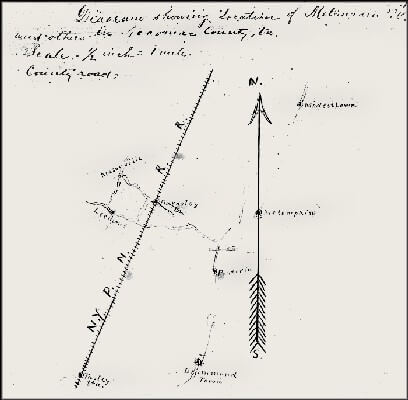

| United States Post Office Diagram, Metompkin, Va. 1915. |

Post offices opened every community on the Eastern Shore to the doings of the world. On Chincoteague in March 1884, thirty-three Northern daily newspapers arrived each day at the post office. Later that year (the year the railroad made its way down the peninsula), the citizens of the hamlet of Muddy Creek campaigned for a post office with feverish dedication. They cleared timber for a new road to Cattail Neck, and a Democratic storeowner in hopes of attracting the good favor of the new administration renamed his establishment "Cleveland" for the President-elect. Post offices established nodes on a greater network and, in effect, helped attract roads, banks, hotels, services, stores, and residences. Once a place obtained postal service, its citizens were equally determined not to lose it or see it curtailed. When one small town had its mail service to the Accomack County courthouse cut to three days a week, its citizens demanded "equal rights."26PE, March 29, August 30, November 29, 1884, and for the loss of service and its implications see May 16, 1885.

|

| Timeline Featuring Cumulative Number of Post Offices on Eastern Shore, 1793-1910. |

The post office's effects on the ways local citizens understood their landscape were not confined to the race for town status. Postmasters, responding to federal requests, filled out annual reports on their offices' activities and reach. These reports grew in sophistication and detail over the 1880s and 1890s. By the turn of the century postmasters recorded postal routes and areas of service on a map of concentric circles showing the extensive and intensive network they oversaw. New understandings of space, time, service, and the perceived "rights" of citizens who interacted with the post office mixed in these years, yielding a modern world built on tangible and intangible networks.27US Post Office Department, Reports of Site Locations, 1837-1950, Microfilm Publication M1126 (Washington: National Archives, 1980).

Imagining the Railroad

The railroad came to the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay after decades of planning. First proposed in the mid-1830s, a line was surveyed in 1837 by the War Department at the behest of a Senate resolution. Independently, the state of Maryland commissioned a study to explore the prospects for a line along the Eastern Shore 118 miles from near Wilmington, Delaware, to Tangier Sound on the Chesapeake Bay. The Maryland commissioners found that the region was full of marshes and "deficient of good roads," and as a consequence cut off from communication with the rest of the state. These "natural obstacles" led them to see the peninsula of Maryland and Virginia as uniquely suited to the railroad. The watercourses were so variable and "deeply indented" that the railroad's straight course might offer more efficient and "natural" means of transportation. With the extraordinarily flat landscape and abundant lumber for ties, the Eastern Shore appeared to be made for rails.28Report of the Commissioners of the Eastern Shore Railroad to the Governor of Maryland, January 24, 1837, p. 7, in Report and Estimate in Reference to the Survey of the Eastern Shore Railroad, US Senate, 24th Congress, 2nd Session, Document 218 (1837). See also James Kearney, "Report of the Engineer of the Eastern Shore Railroad," Farmers' Register 4 (1836), 552-554; G. L. Champion, "Eastern Shore Railroad," Ibid. 6 (1838), 246-247; Charles W. Turner, "The Early Railroad Movement in Virginia," Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 55 (October, 1947), 367.

To these advantages the commissioners added others. The lands of the Eastern Shore's interior, so far removed from water-born commerce, were ripe for planting. Their state of natural "manure" meant that these marginal lands needed only the railroad to unlock their great potential. The railroad, furthermore, would place the region at the crossroads of American geography on the eastern seaboard. They were confident that the rush to build railroads "cannot fail to convey toward the seaboard." Indeed, they expected the Eastern Shore line to profit less from local traffic than from “the business which the railroads of the South will bring towards the Eastern cities."29US Senate, 24th Congress, 2nd Session, Document 218 (1837).

Little came of the commissioners' plans for an Eastern Shore line until well after the Civil War. Surveying for the line into Virginia began in 1874, as building proceeded through Delaware and Maryland. In September the white and newly-enfranchised black citizens of Northampton County voted across racial lines to raise $10,000 for purchasing the right-of-way for the new railroad. The vote was 1,014 for the appropriation and just 35 against it. "Our people are delighted with the result," a Northampton man proclaimed, "and now we want to hear the whistle blow to put down brakes, and cry out, 'All aboard!'"30Better than three-fifths of Northampton's registered voters participated in the referendum. Registered black voters outnumbered white by nearly two to one (Norfolk Landmark, January 31, September 24 [quotation], 1874). In the 1850s and early 1860s several abortive attempts were made to build a railroad down the peninsula. William Mahone surveyed the line in 1854 (Nelson Morehouse Blake, William Mahone of Virginia: Soldier and Political Insurgent [Richmond: Garrett & Massie, 1935], 33-34; December 13, 1859, Accomack County Legislative Petitions, 1776-1862, microfilm, Library of Virginia, Richmond; Mears, "The Eastern Shore of Virginia in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries," II, 589). The route was surveyed a final time in 1881 and 1882 (John C. Hayman, Rails Along the Chesapeake: A History of Railroading on the Delmarva Peninsula, 1827-1978 [n.p.: Marvadel Publishers, 1879], 71).

The new sounds of the industrial age, however, took much longer to arrive than anyone thought possible. The depression of the mid-1870s slowed the railroad's progress to a crawl. In 1878 the Virginia legislature chartered the Peninsula Railroad Company to build a line along the Eastern Shore, but four years later local promoters were still waiting for the line to extend down the peninsula and erase "the doubts of those who have been most persistent in saying that the 'railroad would never come.'" When finally it seemed as if the railroad would be built on the Eastern Shore, a local attorney pointed out that its origins were forty-six years old. Few residents could contain their excitement at the prospect. The railroad "will bring to light our undeveloped resources, improve our lands in productiveness and value," one predicted. "In a word, it will force us from the groove in which we have spun for two centuries and a half and put us upon a level with this progressive age."31PE, January 19 (first quotation), February 23 (second quotation), 1882.

The Pennsylvania Railroad Comes

Finally, in 1884 the Eastern Shore not only had a railroad but also one of the largest corporations in the nation operating in its midst. The Pennsylvania Railroad had entered into a traffic agreement with the Peninsula Railroad, now renamed the New York, Philadelphia and Norfolk Railroad Company. With this powerful connection the Eastern Shore's transformation seemed foreordained to many residents. It was to become the produce "garden" of the cities, the place of rest and relaxation for urbanites, the orchard land of the east coast. William L. Scott, the Erie, Pennsylvania, coal magnate who was a leading investor in the New York, P&N, expected that the railroad would bring a "great revolution" in the variety of agricultural products that would enter the Philadelphia and New York markets. He noted the gentle climate of the shore, which he compared with Marseilles, France, and the superb quality of the soil, which, he said, exceeded that of Long Island.32Peninsula Enterprise, April 19, 1884; Hayman, Rails Along the Chesapeake, 70-72; "Our Peninsula - As the Hon. Wm. L. Scott See It," Philadelphia Times, April 18, in PE, April 25, 1885. The Pennsylvania Railroad did not purchase the capital stock of the New York, Philadelphia and Norfolk until 1908 (H. W. Schotter, The Growth and Development of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company: A Review of the Charter and Annual Reports of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, 1846 to 1926, Inclusive [Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Railroad Company, 1927], 309-310).

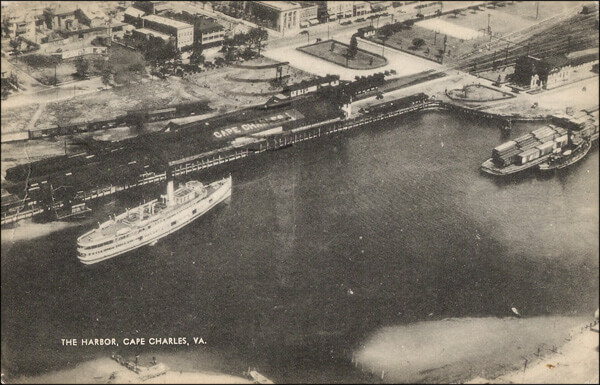

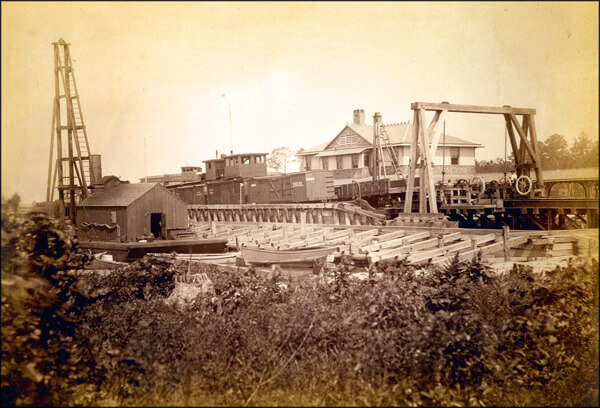

The natural features of the region were not the only sources for the bright future that William Scott envisioned. At a cost of nearly $300,000, the N.Y., P. & N. was dredging a new harbor out of a large fresh-water lagoon between King's and Old Plantation creeks in lower Northampton County, and Scott planned to develop a new town around it called Cape Charles City. The appellation "City" for any place on the Eastern Shore was romantic, a vision of the future that the railroad might make possible. To dramatize the opportunities, Scott suggested, "Take a compass and draw a circle over the lower Chesapeake, within a radius of seventy-five miles of Cape Charles, and you will find that 18,000,000 bushels of oysters are gathered every year, while there are only about four millions taken from all other waters of the country."33"Our Peninsula - As the Hon. Wm. L. Scott Sees It" Philadelphia Times, April 18, in PE, April 25, 1885; Letter from the Secretary of War, Transmitting Reports on the Survey and Preliminary Examination of the Harbor and Approaches of Cape Charles City, Va., US House of Representatives, 51st Congress, 1st Session, Document 29.

Cape Charles City and its harbor were planned as a hub for traffic flowing via steamboat and barge to and from Norfolk where numerous railroad lines extended South and West. Less than a year after its founding, a reporter described the place as "an embryo city . . . with a breakwater, long piers, and sundry warehouses and other buildings." In 1887 the Pennsylvania, the N.Y., P. & N., and the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad agreed on a traffic arrangement, the "Atlantic Coast Despatch," which greatly facilitated the shipment northward of Southern early fruits and vegetables. A few years later the N. Y., P. & N.'s allies in Congress placed Cape Charles harbor in the River and Harbor Act. In 1890 the Corps of Engineers dredged the harbor basin, its entrance, and a channel through Cherrystone Inlet and built stone jetties protecting the harbor outlet. By 1912 the Corps estimated that Cape Charles harbor handled 2,500,000 tons of freight a year.34"The Eastern Shore," New York Evening Post, April 25, 1885 (quotation); Howard Douglas Dozier, A History of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1920), 124-125; James L. McCorkle Jr., "Moving Perishables to Market: Southern Railroads and the Nineteenth-Century Origins of Southern Truck Farming," Agricultural History 66 (Winter, 1992), 54; HR (51-1) Doc. 29; Letter from the Secretary of War, Transmitting, With a Letter from the Acting Chief of Engineers, Report on Examination of Chesapeake Bay, with a View to Straightening the North Side of the Channel at the Entrance of the Harbor at Cape Charles City, Virginia, and to Increasing the Width of the Channel 200 Feet, US House of Representatives, 62nd Congress, 3rd Session, Document No. 1112.

Over the next several decades the N.Y., P. & N. continued to expand and improve its infrastructure. Beginning in 1906, the railroad double-tracked its line using heavier rails and in 1912 completed an extension Southward from Cape Charles City to Kiptopeake. It installed a block signal system in 1908, substituted telephone for telegraph dispatching in 1912, and replaced manual signals with electric in 1923. It built new shops and offices at Cape Charles City in 1910 and all the while added and upgraded sidings. Boxcar capacity increased from 40,000 lbs. in the 1880s to 100,000 in 1901. Boxcars were equipped with ventilators for the shipment of seafood and vegetables and after 1913 were of all-steel construction.35Eastville Eastern Shore Herald (hereafter cited as ESH), June 1, 1906, March 29, 1912; Hayman, Rails Along the Chesapeake, 84; Kirk Mariner, "Remembering the Old Cape Charles Railroad," Tasley Eastern Shore News, April 19, 2006; PE, January 27, 1923; Frederic H. Abenschein, "Pennsy's Perimeter of Plenty," The Keystone 31 (Summer, 1998), 28.

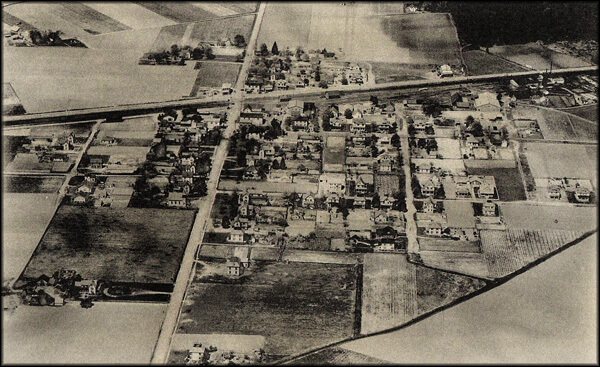

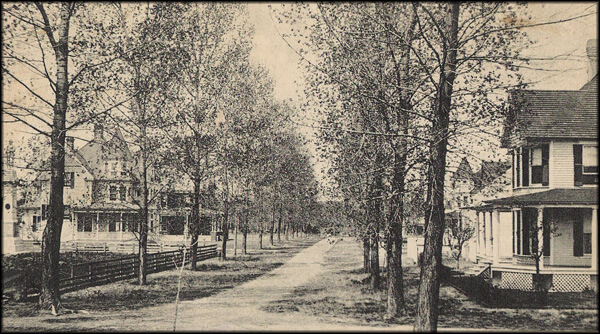

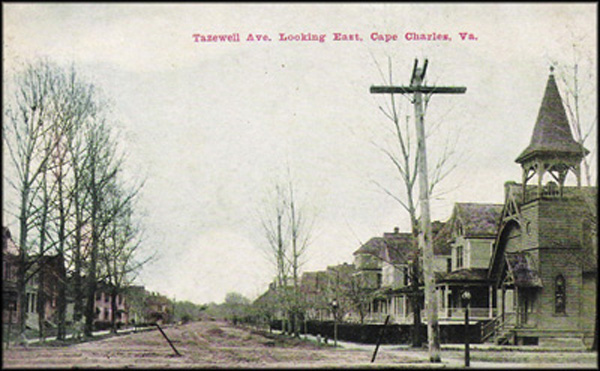

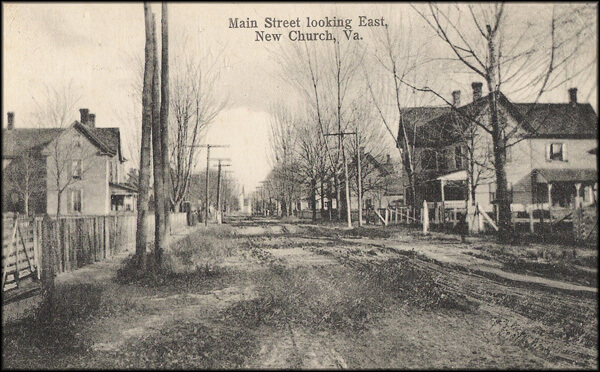

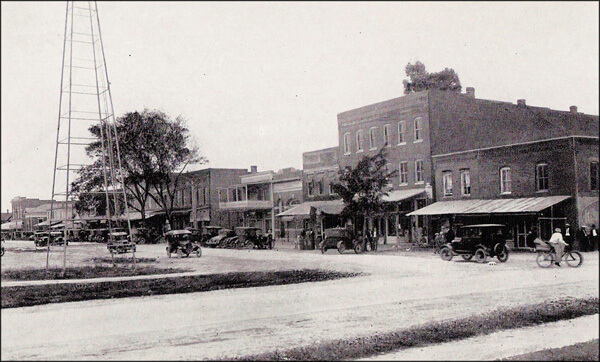

Where the earliest travelers on the new rail line had seen "little except pine forests, corn fields, fallow fields and here and there a farm house surrounded by a few fruit trees," those that followed soon after discovered "new settlements appearing, and buildings going up wherever a station has been built." From the new depots (eventually numbering twenty-eight) rail cars carried away seafood from the Broadwater, mine props from the swampy forests of the upper Accomack bayside, and produce — onions, cabbages, strawberries, and sweet and white potatoes — from the peninsula's farms. "The stimulus of profitable trade piles up the stations with their produce," an Englishman observed, "for they are engaged in feeding populations numbering several millions, from 200 to 500 miles northward. The rapid trains for the quick delivery of produce go as far as Boston, and in some cases to Canada. In 12 hours the fresh and tempting fruits and vegetables are delivered in New York, in 20 hours in Boston, and in 30 hours in Montreal." A few of the depots remained villages busy only at the harvest, but others grew rapidly into towns.36"Our Peninsula," Wilmington Morning News in PE, November 22, 1884 (first quotation); "New York, Philadelphia and Norfolk Railroad," London Times, October 11, 1887, in PE, January 7, 1888 (second quotation); Mears, "The Eastern Shore of Virginia in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries," II, 592-593.

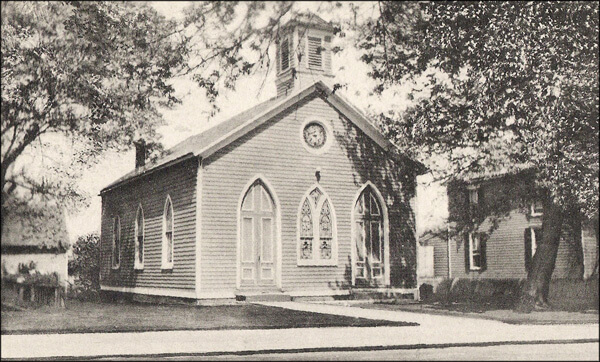

The towns developed as nodes on a greater network, as residents rearranged the landscape around the railroad. Local people, not the railroad corporation, developed most of the railroad towns. All were laid out in a more or less regular pattern with their business districts adjacent to and often facing the rail yard and their residential neighborhoods, developed by different people at different times, laid out in square or rectangular blocks. Cape Charles City and Parksley, planned by Northern investors, were more formally arranged. They were laid out in a grid with lots reserved not only for businesses and residences but also for a variety of community purposes. One of Parksley's founders boasted that "foresight was shown in the reservation of a five acre site to be maintained as a park on the west side of the railroad and a one acre lot on the east side to be used as a playground. An additional five acres were reserved for school buildings and two choice lots were granted to each church which applied for same."37PE, December 6, 1902; Jim Lewis, Cape Charles: A Railroad Town (Eastville, Va.: Hickory House, 2004), 9-11; J. B. H. Carter, C. W. Holland Jr., W. E. Johnson, and C. L. Miller, "An Economic and Social Survey of Accomac County," University of Virginia Record Extension Series XIII (March, 1929), 5-6 (quotes H. R. Bennett).

A network of new roads soon connected the countryside to the railroad towns. Neither stream nor swamp discouraged the farmers, watermen, and lumbermen who yearned for more direct access to the rails. In 1898, for example, the haul between the seaside necks and the station at Painter was shortened by the bridging of the Machipongo River. Meanwhile, Slutkill Neck on the bayside was more directly linked to the depot at Onley by the building of multiple spans across the upper reaches of Onancock Creek. Before the coming of the railroad, the Eastern Shore's road pattern had resembled a grid with the north to south roads (known as the seaside, middle, and bayside roads) crossing those running east to west from sea to bay. Now it more closely resembled a sequential series of webs emanating from each of the railroad towns. So intricate had the pattern become that an architectural historian writing in the 1970s mistakenly attributed its origin to medieval England.38PE, June 25, October 15, 1898; Emma LeCato Eichelberger, "The Little Old Town of Quinby," PE, May 7, 1953; H. Chandlee Forman, The Virginia Eastern Shore and its British Origins: History, Gardens and Antiquities (Easton, Md.: Eastern Shore Publishers' Association, 1975), 5.

Towns Emerge Where Railroad and Commerce Meet

The Railroad's Direct and Indirect Effects

Introduction

In 1915 the leading agriculturalists in the nation took the railroad to the Eastern Shore of Virginia to study how the tiny peninsula had become a worldwide force in the potato market and in the process created a vital, wealthy, and by all accounts successful agrarian society. Clarence Poe, editor of the Progressive Farmer, was especially interested in the doings of the Eastern Shore Produce Exchange. He labeled it a "$5,000,000 truck marketing association" and proclaimed it one of the leading examples in the nation of the staggering profits that were possible in agriculture. The tightly-run exchange had shocked the financial establishments in Baltimore and Philadelphia when it declared a dividend of 70 percent.39Clarence Poe, How Farmers Cooperate and Double Profits (New York: Orange Judd Company, 1915), 113-122; PE, November 22, 1902; "Big Dividends for Farmers: How Agriculturists of the Eastern Shore Combined for Self-Protection and How Their Combination Works," Baltimore Sun, December 7, 1902. For the best, recent examination of a farmer's cooperative, see Victoria Saker Woeste, The Farmer's Benevolent Trust: Law and Agricultural Cooperation in Industrial America, 1865-1945 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998).

|

| The headquarters of the Eastern Shore of Virginia Produce Exchange stood adjacent to the rail yard in Onley. "Do not make the mistake of supposing that Baltimore can ever become the distributing point for Eastern Shore goods," the general manager of the Exchange warned a Baltimore reporter. "The little country town of Onley, Va., is now the distributing point and will be such so far as man can see into the future. Don't you know, sir, that we can get as good rates from this point as Baltimore or Philadelphia or New York can possibly get?" |

Steady economic growth had followed the coming of the railroad to the Eastern Shore but a boom awaited the end of the decade-long depression of the 1890s. Revived prosperity in the urban North now combined with a growing population, both native and immigrant, to increase demand for fruits and vegetables. Although possessing favorable geographic and transportation advantages, Eastern Shore farmers hitherto had failed to enjoy the returns that the expanding market seemed to promise. "In pre-prosperity days on the Eastern Shore," an observer later remarked, "the farmers knew how to grow potatoes and grew them. But they didn't know how to market them, and so they weren't marketed. They were consigned to their fate, which more often than not was a tragic one." On occasion, returns were so small that farmers were paid in postage stamps. In 1900 a group of Eastern Shore farmers and businessmen sought to improve the region's position in the volatile national produce market by incorporating as the Eastern Shore of Virginia Produce Exchange.40Twelfth Census of the United States, Taken in the Year 1900: Agriculture, Part II, Crops and Irrigation (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1902), 311; Sharrer,Terry. A Kind of Fate: Agricultural Change in Virginia, 1861-1920 (Ames: Iowa State University Press), 147; McCorkle, "Moving Perishables to Market," 42-43; James L. McCorkle Jr., "Southern Truck Growers' Associations." Agricultural History 72 (Winter, 1998), 79-80; William Harper Dean, "Potatoes - F.O.B. Eastern Shore: What Their Exchange Did For the Virginia Growers," Country Gentleman, July 5, 1919, in PE, August 2, 1919 (quotation); Benjamin T. Gunter, "Farm Group Activities," PE, August 10, 1929; Acts and Joint Resolutions Passed by the General Assembly of the State of Virginia, during the Session of 1899-1900 (Richmond: Superintendent of Public Printing, 1900), 194-195.

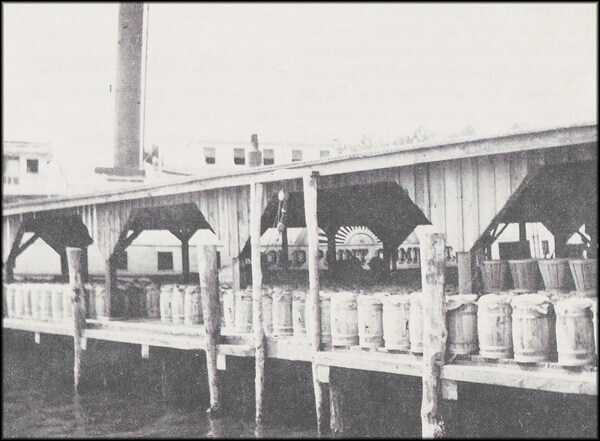

The Eastern Shore Produce Exchange

The Eastern Shore Produce Exchange offered shares at $5 each to white farmers. No subscriber could own as much as one-tenth of the total stock and most of the shares were held in blocks of one to five. Black farmers were not allowed to participate as shareholders but could use the Exchange to market and sell their crops and were eligible for the frequently lucrative patronage dividend. By 1915 the organization had 2,500 stockholders and, extending its services to 1,000 non-stockholding farmers, controlled 75 percent of the potato crop on the Eastern Shore. The Exchange expanded the potential market for local produce by employing agents in cities throughout the North and Midwest. Where once farmers had consigned their crops to a handful of commission merchants in five or six cities on the Atlantic coast, within two years of its founding the Exchange directly supplied over one hundred customers in more than twenty states. "By its system of distribution, in finding customers all over the country," an Accomack man noted, "it has contributed its part in relieving the demoralizing congestions of shipments to New York, Boston and Baltimore of a few years ago." By 1930 the Exchange had further extended its network to 616 cities in the United States, Canada, and Cuba. The Exchange improved the reputation of Eastern Shore produce by requiring that goods shipped under its Red Star brand be subjected to tight quality control (previous to the Exchange, some Eastern Shore farmers had packed pumpkins in the bottoms of barrels of sweet potatoes). Twenty-eight local boards organized and coordinated the activities of Exchange agents who inspected and graded the produce shipped from forty depots and wharves on the peninsula. The Exchange also bought seed potatoes in bulk and negotiated with (and on occasion brought legal action against) the railroad and steamboat companies for better freight rates.41Poe, How Farmers Cooperate and Double Profits, 113-122; Gunter, "Farm Group Activities," PE, August 10, 1929; W. A. Burton, "A Review of the Potato Industry of the Eastern Shore of Virginia," Chicago Potato World in PE, March 17, 1939; William Gordy, "The Organization and Development of the Eastern Shore of Virginia Produce Exchange," PE, August 1, 1931; PE, August 9, 1902 (quotation); "Onancock: The Year One of Continued Prosperity on Eastern Shore," Richmond Times-Dispatch, January 1, 1906. For an example of pumpkins packed in barrels of sweet potatoes, see PE, September 25, 1897.

|

| Map of Eastern United States Featuring Cities Linked to Eastern Shore Through Trade. |

The Produce Exchange invested in the latest technologies of the day. From its headquarters in Onley it ran a private telephone system between the local offices and shipping points. It used the telephone and telegraph to receive and monitor prices through its agents in major cities across the nation and world - Chicago, New York, Boston, Pittsburgh, Toronto, Scranton, Havana. The Exchange obliterated economic hierarchies. "Do not make the mistake of supposing that Baltimore can ever become the distributing point for Eastern Shore of Virginia goods," the general manager of the Exchange warned a Baltimore reporter. "The little country town of Onley, Va., is now the distributing point and will be such so far as man can see into the future. Don't you know, sir, that we can get as good rates from this point as Baltimore or Philadelphia or New York can possibly get?" The Exchange pooled the prices for each day’s sales and paid the farmers the prevailing price. The system assured farmers that they would not pay commissions for this service, that they could gain the highest average market price, and that their products would be marketed with a brand, “The Red Star," nationally recognized for quality. The Exchange could handle the sale of 200 to 350 railcar loads of potatoes each day with this system.42Poe, How Farmers Cooperate and Double Profits, 113-122; "The Chesapeake Bay Trade," Baltimore Sun, July 30, 1907 (quotes William A. Burton).

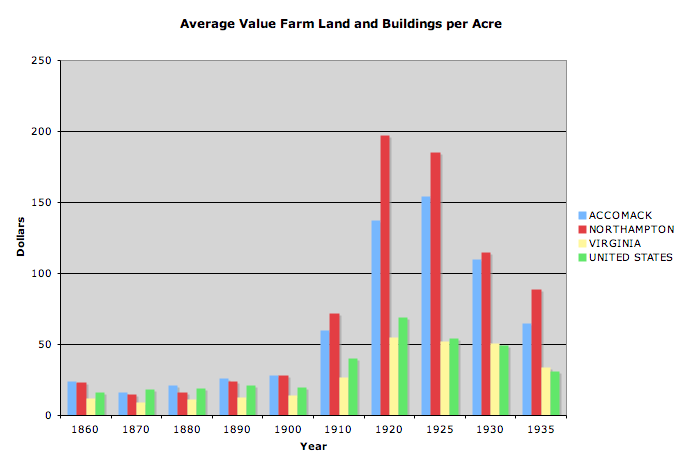

Aggressive marketing and improved quality control stimulated demand for Eastern Shore produce. “Better potatoes of better grades went out in better packages to better markets at better prices than ever in the history of the two counties,” an observer declared. The value of real and personal property increased exponentially. Between 1870 and 1920 the average value of farmland and buildings per acre jumped in Accomack from $16 to $137 and in Northampton from $15 to $197. In 1910 Accomack enjoyed the highest per capita income of any non-urban county in the United States and in 1919 Northampton and Accomack led all American counties in value of crop per acre. Annually, the Produce Exchange alone amassed receipts of $6,000,000 to $7,000,000. The exceptional year of 1920 saw the Exchange’s receipts climb to an astounding $19,000,000. The influx of cash encouraged the formation of new businesses. Between 1880 and 1928 the number of mercantile establishments in Northampton County increased from 46 to 306. Banks, hitherto nonexistent on the peninsula, opened in the larger towns. By 1919, total deposits averaged $7,000,000.43Dean, "Potatoes - F.O.B. Eastern Shore," Country Gentleman, July 5, 1919, in PE, August 2, 1919 (quotation); Charles H. Barnard and John Jones, Farm Real Estate Values in the United States by Counties, 1850-1982 (Washington: United States Department of Agriculture, 1987), 3, 100, 102, 104; Sharrer, A Kind of Fate, 184; PE, January 7, 1922; Gunter, "Farm Group Activities," PE, August 10, 1929; Richmond News-Leader, March 15, 1922, in PE, March 25, 1922; Dun's Mercantile Agency Reference Book, July 1880, July 1928; M. E. Bristow, "Banking on the Eastern Shore of Virginia," PE, December 26, 1925.

The Richmond News-Leader ascribed the Eastern Shore’s prosperity to the Produce Exchange, “adequate and quick transportation,” and the willingness of the farmers to abandon the ways of the fathers, to experiment, and to plant “those products that promise most from the land.” While the News-Leader was correct to identify agriculture as central to the peninsula’s prosperity, it failed to note that the fisheries and lumbering industries were also, in the words of a Northampton man, “on the boom."44Richmond News-Leader, March 15, 1922, in PE, March 25, 1922; ESH, August 10, 1906 (quotation); Baltimore Sun in AN, October 24, 1908.

Packaging and Exporting Potatoes

Prosperity

|

|

The good times encouraged young people to remain on the Eastern Shore and attracted strangers to the peninsula. Between 1870 and 1910 the population nearly doubled, growing from 28,455 to 53,322. In 1906 an official of the US Department of Agriculture noted "the increase of population, especially of young married couples, seeking homes, making new settlements and improving old ones." An indicator of the Eastern Shore prosperity was the growth of its black population. While the black population of Virginia grew by only 24 per cent between 1870 and 1910, that of the Eastern Shore grew by 78 per cent (the Eastern Shore's white population increased by 95 per cent). The demand for labor attracted black immigrants from North Carolina and the Western Shore of Virginia. "This is a promising field for good farm labor," an Eastville man advised, "prices ranging from $1 to $2.50 a day. There are some 500 watermen on the seaside waters getting on an average of $2.50 a day."45Onancock Eastern Shore News (hereafter cited as ESN), October 11, 1940; AN, October 27, 1906 (first quotation); Norfolk Landmark (hereafter cited as NL), October 30, 1901 (second quotation). With the local economy booming across the board, labor enjoyed a seller's market. The fisheries, farming, lumbering, and construction competed year-round for labor. In certain sectors demand peaked at the same time. Tourist resorts siphoned off agricultural workers during the summer, and the fall sweet potato harvest coincided with the opening of the oyster season. When times became slack in an occupational specialty, workers enjoyed opportunities elsewhere. At the close of the oyster season in the spring, oystermen might clam or crab or fish pound nets. In May they might help with the strawberry harvest and in July pick up white potatoes. Or they might drive a timber cart or tend the saw at the local mill. During the winter they might leave the oyster grounds for a day or two to work as guides for Northern duck hunters. None of the labor forces was racially exclusive. Both black and white worked for wages in the fields, in the woods, or on the water. Lumbering was a male preserve and female labor in the fisheries was restricted to the packing houses, but the agricultural harvests, essentially races against spoilage, required the services of all available hands regardless of race, gender, or degree of kinship. 46Stevens, Soil Survey, 31; PE, May 17, 1884, May 22, 1886, May 28, 1887; Etta Bundick Oberseider, So Fair a Home: An Eastern Shore Childhood (n.p.: Author, c1986), 5, 22-23.

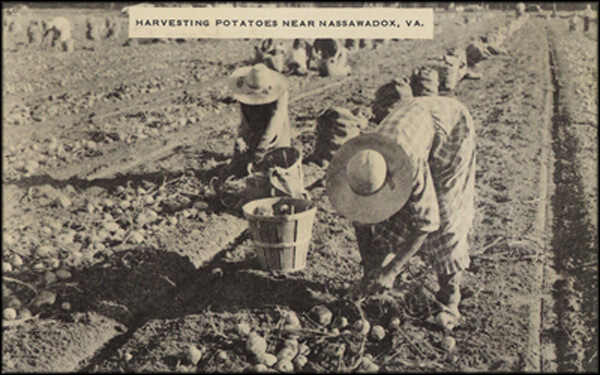

The competition for and flexibility of labor created tensions between workers and employers. In the seafood industry these found expression in occasional and usually successful strikes of oyster tongers and shuckers. In agriculture, tension was especially high at the harvest when farmers worried that their crops might rot in the fields for want of hands to pick them. Racial animosity and distrust exacerbated the situation. A dispute over farm wages set the stage for a minor race riot at Onancock in 1907. As white potato production increased exponentially in the 1910s and 1920s, Eastern Shore farmers employed black migrant laborers to help with the harvest. The farmers themselves were, overwhelmingly, small holders well acquainted with the physical demands of farm labor. A woman who grew up on an eighty-acre farm at Nelsonia recalled that for her father "it was up with the sun all spring, summer, and fall, a short stop for lunch, then back to the farm until sunset. He tilled the fields, planted white potatoes, corn, sweet potatoes, hay, and rye. He scattered clover seed and together he and God raised the crops."47PE, February 9, 1884, March 16, 1895; Brooks Miles Barnes, "The Onancock Race Riot of 1907," Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 92 (July, 1984), 336-351; Oberseider, So Fair a Home, 21 (quotation). The Bundick farm "was more than one man could take care of, and we always had one tenant, and sometimes two" (Ibid., 5). Further research has shown that Barnes's analysis of the labor situation was far too facile. For migrant labor see Cindy Hahamovitch, The Fruits of their Labor: Atlantic Coast Farmworkers and the Making of Migrant Poverty, 1870-1945 (Chapel Hill and London: University to North Carolina Press, 1997).

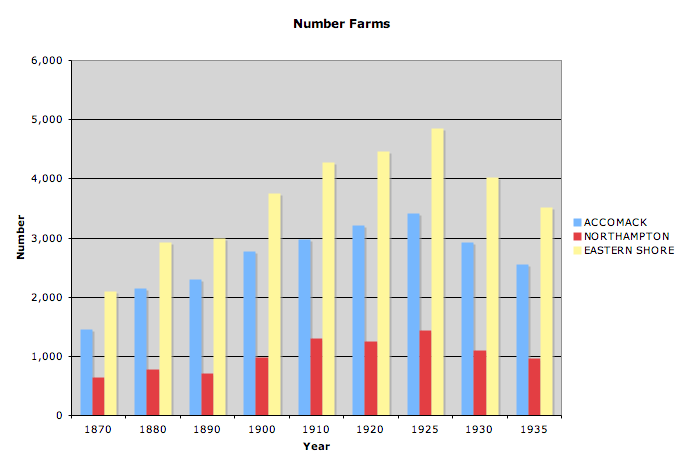

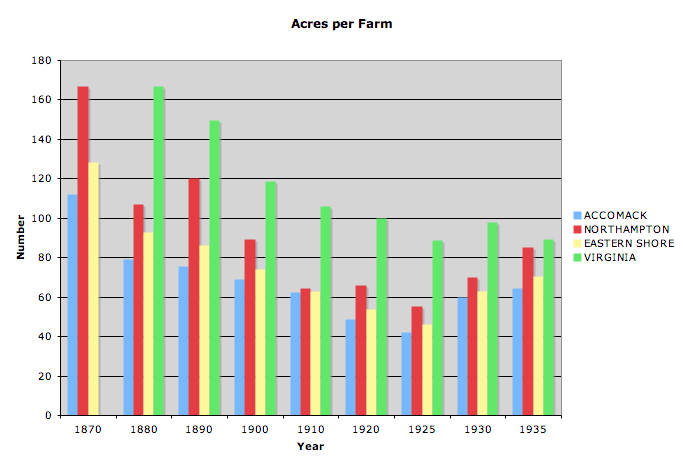

The expanding population put pressure on the supply of farmland. Farms were divided and sub-divided. As early as 1891 an Onancock man had discovered "a tendency to break up the larger estates of former days and divide them into small farms that can be easily cultivated by two or three men." Between 1890 and 1925, the number of farms in the two counties increased from 2,997 to 4,856 while the average acreage decreased from 86 to 46.1. Curiously, throughout the period the acreage under cultivation remained about the same. In Northampton County farmers brought only 646 new acres under cultivation notwithstanding the value of land increased by over 700 per cent. The farmers' need to preserve their woodlots thwarted the impulse to break new ground. The farmers valued their woodlots as windbreaks protecting the peninsula's level fields and as a source of lumber for building and repair, for fence, and for stove wood. They valued it as a refuge for insect-devouring birds and for the game they so loved to hunt. The farmers especially valued their woodlots as a source of pine needles. "Ever since truck raising displaced general farming, pine needles have been used as a substitute for straw as bedding and as a source of humus," a forestry expert explained. "A truck farm without an adequate supply of pine 'straw' or 'shats' could scarcely compete with its more fortunate neighbors. It would be difficult to place a monetary value on this resource, but it is generally recognized that the trucking industry, as now organized, is largely dependent upon forest litter as a source of humus." Although the Eastern Shore was wealthier in 1920 than in 1910, the latter year's population of 53,322 remained the peninsula's historic high. Farm size had reached its practical minimum. The smaller the farm, the more intensively it must be cultivated to achieve a decent standard of living. Prosperity could not be sustained by ever-smaller farm units divided among an ever-greater number of farmers. Population growth necessarily halted.48"Onancock: The Year One of Continued Prosperity on Eastern Shore," Richmond Times-Dispatch, January 1, 1906; Frank P. Brent, The Eastern Shore of Virginia: A Description of Its Soil, Climate, Industries, Development, and Future Prospects (Baltimore: Harlem Paper Company, 1891), 4-5 (first quotation); Carter, "An Economic and Social Survey of Accomac County," 54; C. W. Holland Jr., N. L. Holland, and W. W. Taylor, "An Economic and Social Survey of Northampton County," University of Virginia Extension Service Series XII (November, 1927), 35, 37 (quotes Wilbur O'Byrne), 38; Wilbur O'Byrne, "More and Better Pines on the Eastern Shore,"ESN, October 23, 1936. For the necessarily more intensive cultivation of small farms see John Fraser Hart, The Rural Landscape (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 279.

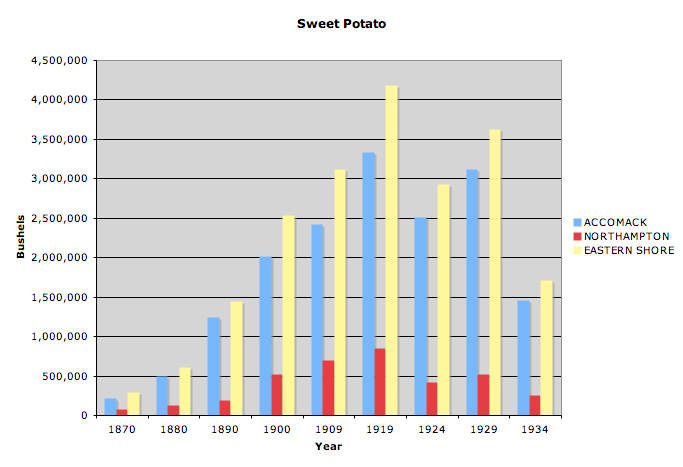

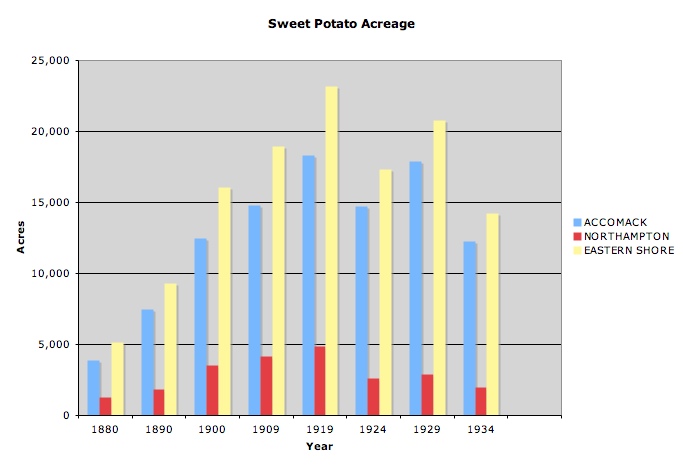

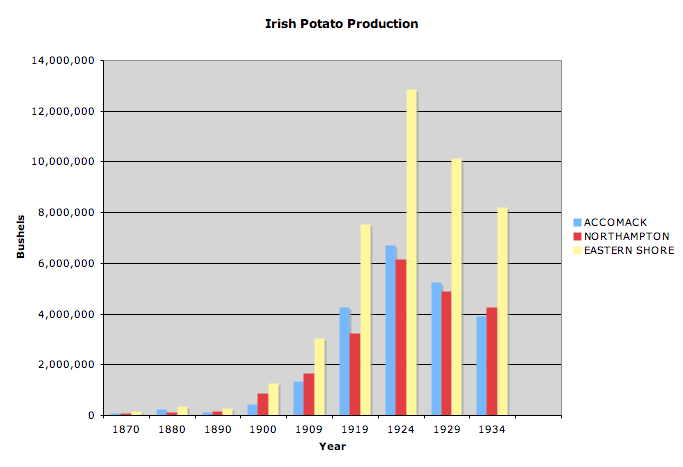

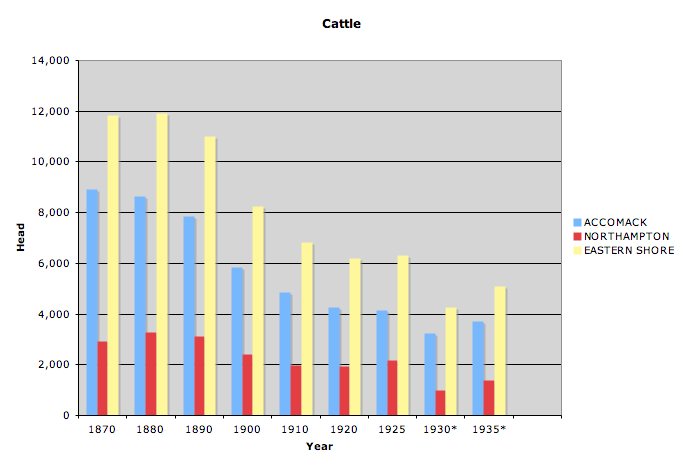

Eastern Shore farmers compensated for the dearth of cropland by dramatically increasing the yield of their staple crops. From 1900 to 1924, sweet potato production increased from 2,529,339 bushels to 2,932,849 while that of white potatoes increased tenfold, from 1,269,055 in 1900 to 12,873,750 in 1924. "Back in 1907," a railroad official remarked in 1919, "we used to get a little chill of joy up and down our spinal columns if we could see a million barrels of white potatoes promised at harvest, if we don't get 3,000,000 barrels now we feel sick." In 1928 the Produce Exchange alone required 14,153 boxcars to move the white potato harvest, a logistical demand that tested the organization and ingenuity of the Exchange and of the railroad. Farmers achieved the increased production by a greater concentration on potatoes (although onions, cabbages, and strawberries remained important cash crops and corn was grown to feed livestock), by improved farm machinery, by the use of pesticides to control the Colorado potato beetle, and by the liberal application of fertilizer. Expenditures for fertilizer increased from $63,000 in 1879 to nearly $1,000,000 in 1909. The end of the open range in the early 1900s also helped by curtailing the depredations of foraging animals and by reducing the farmers' expenditures of time and money on the erecting and mending of fence.49Dean, "Potatoes - F.O.B. Eastern Shore," Country Gentleman, July 5, 1919, in PE, August 2, 1919 (quotation); PE, January 19, 1929; Stevens, Soil Survey, 18, 20, 21, 24, 25; Sharrer, A Kind of Fate, 56; ESH, March 24, 1905. For the use of fertilizer in the South see Douglas Helms, "Soil and Southern History," Agricultural History 74 (Fall, 2000), 751-752.