Overview

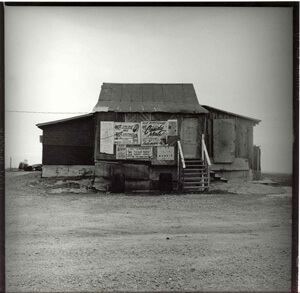

Transformed in the 1950s from a sharecropper shack that was built probably in the 1920s, Poor Monkey's Lounge is the one of the last rural jook joints in the Mississippi Delta. There are several remaining urban jooks, and some modern reincarnations designed to reflect old time places, but virtually no rural jooks remain. These places were once common. Before the Great Migration to the North and the exodus to towns and cities, hundreds of thousands of sharecroppers and small farmers peopled the countryside in the days when one person and one mule worked ten acres. Today, on this depopulated countryside, one tractor works a thousand acres. The effects of TV, and the appeal of casinos, recorded music, iPods, and restaurants have also drawn customers away.

Poor Monkey's epitomizes the jook, the kind of place where the Blues was incubated until it gelled into a recognizable art form. As one local woman told me recently, when you go to a jook, you feel like everyone there is all one person, all sharing the same feelings.

Introduction

|

Poor Monkey's sits in a cotton field in Bolivar County, west of the town of Merigold on the Hiter farm, land worked by members of the same family for generations. Monkey's is the only surviving sharecropper shanty on this land, although there are remains of a few others nearby. In the early 1950s, Willie Seaberry, known as Poor (Po') Monkey, began to operate the unused sharecropper house as a lounge.

(Enlarged Map: Poor Monkey's and Merigold)

The building is made of unpainted cypress planks, roofed with corrugated galvanized steel that is often referred to as a "tin." It is windowless, but has three doors. The front sports several faded, hand-painted signs. One describes the dress code by saying "not like this" next to a picture of a man with his cap on backwards, and "not like that" next to an image of a man with his underpants showing above his waist. Other signs tell patrons not to bring beer inside, "no loud music" (consistently spelled "lounld"), and "no dope smoking."

|

Lounge

|

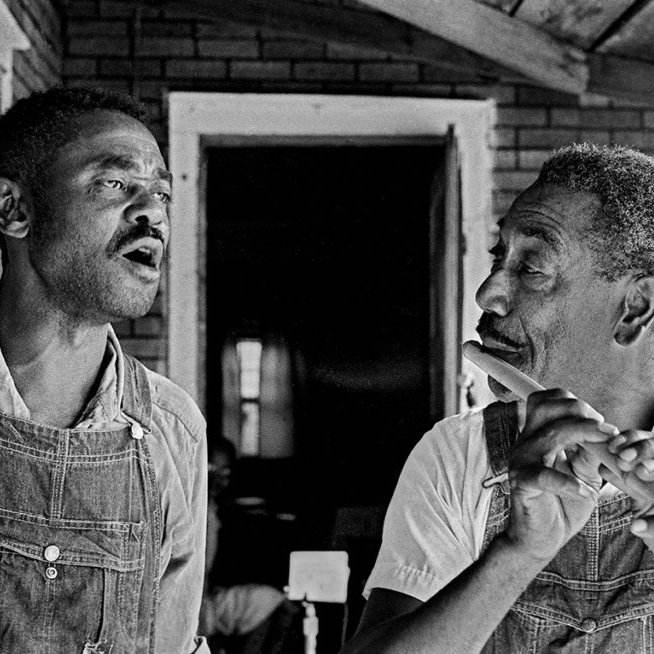

| Suli Yi, Conversation, Poor Monkey's, near Merigold, Mississippi, November 2004. |

In the early twenty-first century, Poor Monkey’s is only reliably open Thursday nights, starting around 8:30 and closing in the early hours of Friday morning. This is the night Po’ Monkey calls “Family Night,” and many people in the Delta will tell you that the weekend starts then. Guests are met at the door, either by Monkey or one of his regular greeters. Admission is normally $5. A DJ plays soul blues, R&B, and soul. Beer and soft drinks are sold from the kitchen through a Dutch door. Many customers bring their own Crown Royal, which is acceptable as long as they buy mixers. By ten o’clock, although the lounge grows smoky and raucous, a code of behavior operates: no drugs, no violence, no disrespect.

The Poor Monkey crowd is made up almost entirely of local regulars, and is usually integrated. It is not uncommon to meet an American travel or blues writer or a visitor from Europe or Asia, and these special guests are taken around the room by Mr. Seaberry and introduced to the regulars, who are generally eager to talk. Crowds rarely exceed two dozen at any given time. Traditional blues bands as well as fraternities from nearby Delta State University sometimes book the lounge, but these uses don’t interfere with the Thursday night routine.

|

|

| Luther Brown, Outside Rules, Poor Monkey's near Merigold, Mississippi, 2005. |

Seaberry's small space has also made a mark on the global landscape. Poor Monkey’s Lounge has been featured as a cover photograph of the Oxford American, a two-page spread in Annie Leibovitz’s American Music, photos in Vanity Fair and Esquire magazine’s Japan edition. Newspapers from the Memphis Commercial Appeal to the New York Times have published descriptions and photos. The floor plan of the lounge has been analyzed as an example of vernacular architecture in Mississippi Folklife. The Lounge and Willie Seaberry were featured in a two-hour Japanese television show, and a Voice of America television broadcast to Chinese viewers. Bluesman Floyd Lee filmed a portion of his bio-pic here, and websites feature the Lounge in English and French.

The Hiter family gave Mr. Seaberry a lifetime lease on the property. There are some locals who would prefer to see the place end after Seaberry’s death, since he is personally so much a part of it. Others would like it preserved, and some have even suggested that it should be moved and “cleaned up” as was done to the log cabin that Muddy Waters grew up in. The Delta Center for Culture and Learning is filing preliminary paperwork to have the building added to the National Register of Historic Places, and the Bolivar County Board of Supervisors renamed the nearby road, "Poor Monkey's Road." Tour groups stop here regularly, as do college students on field trips from around the United States.

NOTE: In early spring 2006, Seaberry started calling the Lounge, "Poor Monkey's Social Club."

Video

Poor Monkey's, Fall 2005. This short clip offers a glimpse inside the space as blues musician Big George Brock performs.

Poor Monkey

|

| Suli Yi, Willie Seaberry holding a copy of the November 2004 Esquire magazine Japan, which featured an article about him and the lounge, November 2004. |

Since 1963 Willie Seaberry has lived in a tiny single room of the building, filled almost completely by his bed. A slightly larger kitchen serves as a bar when the lounge is open, and the rest of the building includes space for several large tables, a pool table, and a stage area for live bands or a disc jockey. Sixty to seventy people can dance, move around, or sit.

Seen from the outside, the lounge is a shanty. Inside, the space opens into an array of colors and sounds. Three mounted TV sets display different programs. Strings of Christmas and rope lights flash. A disco ball reflects a rainbow of colors off walls covered either with foil or loud floral prints. Large, cut-out letters spell "Season’s Greetings" year round, and tinsel in multiple lengths and shapes hangs from the ceiling. Walls are carpeted with photographs of images ranging from school graduation to promotional shots of strippers. Stuffed or sculptural monkeys, some amended with a plastic banana or a lifelike dildo, hang from beams or sit in corners, along with a few naked plastic baby dolls. A sign over the Dutch door separating the kitchen from the main public space, through which beverage purchases are passed, reads, "This is a high class place. Act respectable."

|

In one corner stands a large, welded-metal sculpture of Willie Seaberry holding a guitar, made by Monkey’s friend Larry Grimes. From the sculpture’s mouth protrudes a bolt with a red end, representing Monkey’s signature cigar. Attached to the sculpture’s waist is a pair of handcuffs, perhaps indicating that he is the local "law." A monkey sits on the sculpture’s head. At the far end of the main room is the DJ’s booth, surrounded by large speakers and a huge sign advertising Heineken beer.

|

| Kathleen Robbins, Willie Seaberry Inside Poor Monkey's With Customers, February 2003. |

On most Thursdays, an elderly man sits quietly behind the DJ on a stool. This is "Dr. Tissue," who has been a fixture at the Lounge "from the beginning" according to Mr. Seaberry. On Halloween, 2005, a wooden military surplus coffin was added to the outside of the Lounge with the words "Rest in Peace Poor Monkey" painted on it and a stuffed toy gorilla sticking out of one end.

The metamorphosis that changes the shanty into a party-land affects its proprietor and his regulars. Most days, as he drives a tractor or operates a cotton picker, Seaberry wears overalls. In his lounge he favors bright, color-coordinated suits, with matching belt buckles, derby or cowboy hats, and boots. If he's feeling up to it, he changes clothing in his bedroom every hour or so and emerges, strutting as if on a fashion show runway, in baby blue, bright white, crimson, yellow, plaid, or even highly reflective silver. Seaberry sometimes further accessorizes his wardrobe with large signs around his neck. One reads "For Sale" on one side, and is flipped over to reveal "Private Property." Another reads "Beer Drinkers Make Better Lovers," with "3 Way or 4 Way" on the reverse.

Recommended Resources

Print Materials

Cheseborough, Steve. Blues Traveling: The Holy Sites of Delta Blues. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2001.

Dellinger, Matt. "Mississippi: The State of The Blues." Oxford American, Summer Music Issue, 2001.

Knight, Richard. The Blues Highway: New Orleans to Chicago. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot Press, 2003.

Komara, Edward (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Blues. New York: Routledge, 2005.

Nardone, Jennifer. "'I Can Sit Right Here, Thinks a Thousand Miles Away' Revealing the Blues in the Space of Jukejoints". Mississippi Folklife, 31 (1999), 20-29.

Palmer, Robert. Deep Blues: The Musical and Cultural History of the Mississippi Delta. New York: Penguin Books, 1981.

Pearson, Barry Lee. "Jook Women." Arkansas Review, 34(1), 18-29.

“Slip Inside the Deep South." Esquire magazine, Japan, 18 (November 2004).

Wang, Ning. "Rethinking Authenticity in the Tourism Experience." Annals of Tourism Research, 26 (1999), 349-370.

Films

Bishop, John M., Alan Lomax and Worth W. Long. The Land Where the Blues Began (The Mississippi Authority for Eduational Television & Alan Lomax, 1979)

http://www.folkstreams.net/film,109

Ferris, Bill. Give My Poor Heart Ease: Mississippi Delta Bluesmen (Yale University Media Design Studio with the Center for Southern Folklore, 1975)

http://www.folkstreams.net/film,80

Links

The Delta Blues Museum in Clarksdale, Mississippi.

http://www.deltabluesmuseum.org/

Downs, Tom. "On the Road- Top Five Juke Joints." Lonely Planet

http://www.lonelyplanet.com/journeys/blues/3.htm

Mississippi Delta Blues Road Trip

http://www.pbs.org/theblues/roadtrip/deltahist.html

Mississippi Delta Blues Website

http://www.mississippideltabluesinfo.com/

Po' Monkey's

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Po%27_Monkey%27s

Rankin, Tom. “Cane Brakes, High Water, Drought: The Mississippi Delta.” Festival of American Folklife Program Book, 1997.

http://www.folklife.si.edu/resources/Festival1997/cane.htm

Sweets, Ellen. "Down in the Delta." DenverPost.com, May 14, 2006.

http://denverpost.com/travel/ci_3803695