Overview

Read together, the "loyalist" plantation romance and the "fugitive" slave narrative speak to one another as symbiotic southern genres, even if only contrapuntally. The plantation romances exhibit considerable anxiety about the stability of the slaveholding South, while the slave narratives are not only stories of flight from the South but of deeply held cultural and familial roots in the South. When Jacobs and Douglass's narratives are grouped under the heading of "Literatures of Slavery" with plantation romances and Anti-Tom novels, the regional dynamic of the antebellum South is clarified for all of these genres.

Introduction

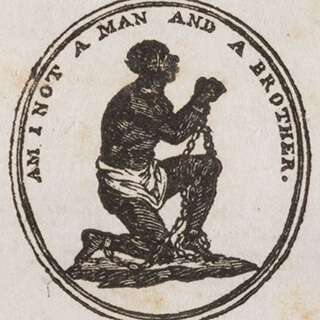

Many of the novels that we call plantation romances also bear a different name: we know them and see them discussed as "Anti-Tom novels," written implicitly or explicitly to counter the negative view of the South that Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) popularized with such amazing force. Even before her novel appeared serially, southern novels set on plantations were responding to abolitionist rhetoric with idealistic portrayals of the master class, embellished with usually silent slaves in the background. The slave narrative, conversely, is viewed as having its impetus as an explicitly abolitionist form, like Stowe's novel (indeed the narratives were an important source for her book's rendering of slave life). The fugitive or freed slaves, writing first-hand accounts of bondage, would hardly be expected to claim to be southerners and might understandably have identified themselves, once free, as radically "Different-From" the region where they had been denied human identity. Yet the narratives actually remind us how deeply slaves "belonged" to the South – not only in the horrifying legal sense but also in terms of their own self-identification, as well as loyalty to their own blood families (not their romantically and falsely defined "white" families).

|

| Harriet Beecher Stowe, "Eliza comes to tell Uncle Tom that he is sold and that she is running away to save her child" from Uncle Tom's Cabin. |

Read together, the "loyalist" plantation romance and the "fugitive" slave narrative speak to one another as symbiotic southern genres, even if only contrapuntally. The plantation romances were written partly as answers to Northern media’s images, yet it is also striking to note some thematic coding within the genre that deconstructs some of the transparent pro-slavery positions they presume to vocate. This genre was perhaps not intentionally one of resistance, yet writers and readers of such works seem to have been unable to avoid using the form not only to promote their way of life but also to express their deep anxieties about it.

Plantation Romances

Three of the most important plantation novels are John Pendleton Kennedy's Swallow Barn, first published in 1832 and then republished with a few revisions in 1851; William Gilmore Simms' Woodcraft, published in 1852, and Caroline Lee Hentz's The Planter’s Northern Bride (1854). All of these novels were written (or revised) within the shadow of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and they can be read as constituting a kind of literary effort at damage control. Yet I would argue that they were doing more than simply building the case for the South as a place "different from" the North. They were also addressing, in a surprisingly resistant way, conditions of upheaval within the South that bear some scrutiny.

I will mention only one intriguing feature of the plantation genre as these three primary examples exemplify it – they all deal centrally with Revolution. Woodcraft, indeed, is set in the period of the Revolutionary War. Its opening scene is also revolutionary in a gendered way: it shows us the remarkable widow, Mrs. Eveleigh, taking on a British naval officer in his cabin in order to demand the return of her slaves, who to her mind are illegally confiscated property. Simms’s setting in the South Carolina countryside, visualized as ravaged by the British forces, is also instructive for an 1850s southern audience. Simms might have been thinking about the 1850s South as coming to grips with itself as a newly constituted revolutionary force, yet he is also expressing a society facing internal and potentially devastating upheaval. It is also notable that his woman character, Mrs. Eveleigh, is the one who has the upper hand throughout the novel, and not as a southern belle but as a savvy, bold, and even cynical central player with no interest in marriage or feminine frills. Why would Simms, in a novel that was taking on Uncle Tom’s Cabin's social criticism of the slaveholding South, make the hero of his southern allegory a proudly independent woman who is empowered to seize the reins of a society in the throes of both externally imposed and internally fraught upheaval? Woodcraft is a novel that is much clearer in expressing the South’s anxiety about power and order than in promoting the South's confidence in its "peculiar institution." And Swallow Barn, as well as The Planter’s Northern Bride, exhibits the same tendency, through similar scenes of troubling revolution. Near its end, Swallow Barn tells the story of the rebellious slave Ned. After a long period of incorrigible behavior, he finally becomes a loyal defender of his owners’ interests, but his early resistance raises a troubling specter – the master-slave relationship was not as uniformly idyllic as the slave owners claimed. The Planter’s Northern Bride dramatizes much more extensively an even darker threat of rebellion. The novel attempts to prove the courage and necessary mastery of its southern planter hero by having him quell an uprising orchestrated by discontent/ed slaves supported by naive abolitionists. All three of these novels reflect, in their odd portrayals of internal upheaval, the vision of a deeply troubled southern planter of an earlier era, Thomas Jefferson. As he looked at his region’s system of manners, he admitted, "I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just . . . that considering numbers, nature and natural means only, a revolution of the wheel of fortune, an exchange of situation, is among possible events . . . The Almighty has no attribute which can take side with us in such a contest." The word "Revolution," sacred to Jefferson’s thinking in one respect, in this statement becomes a terrible threat. The context of Jefferson’s remarks make it clear that the "country" he is thinking about is his own Virginia, that he is not thinking about a conflict involving outside forces – either the British or the American North, but he is thinking about internal rebellion, including foremost the threat of justifiable slave rebellion, as a perhaps foreordained "revolution of the wheel of fortune" for his region, tragically dependent as he believed it to be on "the existence of slavery among us."

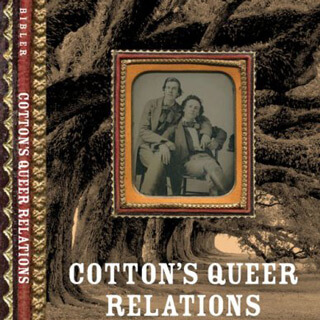

Slave Narratives

What of the slave narratives? This is a genre that we almost always understand within the context of abolitionism and quite obviously as an attack on the South as a society from which the fugitive or ex-slave writer has been by law excluded. True enough – but the slave narrative is inescapably also a southern genre, not merely because those who wrote in this format were born in the South but because the South was where they called upon and preserved their own sustaining cultural resources. In Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), Douglass pays homage to his African heritage in his emphasis on the John the Conqueror root that protected him against the Overseer Covey. He does so again in his explanation of the true meaning of the slaves' singing. It was not, he emphasizes, a sign of their content/ment but a way of expressing common, communal sorrow that reaffirmed an identity quite different from the one imposed by the slaveholders. Another sign of his southern identification is the way in which Douglass fashioned himself as revolutionary hero within his community, a bold and literate leader consciously framed as a counter-image to the plantation romances’ planter Cavaliers.

Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) is in some ways our best example of the slave narrative as an internally resistant southern text. Here is a slave who framed her life story within the twin regional ideals often cultivated in plantation romances: the southern home place and the southern lady. Jacobs escapes initially not to the North, but to the domestic haven of her grandmother’s Edenton home, a refuge for seven years that keeps her in touch with her children and a large extended family. More importantly, she fashions the controlling ideal of the lady in her portrayal of her grandmother: a matriarch of exquisite manners, deep personal virtue, and religious piety. This envisioning makes all the more pointed Jacobs’s intention when she treats the way in which she was harassed by her master, who hypocritically borrowed the “romance” language – telling “Linda” (Jacobs’s pseudonym) that he wanted to “make a lady” of her, to give her finery and a home of her own.

When Jacobs and Douglass’s narratives are grouped under the heading of “Literatures of Slavery” with plantation romances and Anti-Tom novels, the regional dynamic of the antebellum South is clarified for all of these genres. The plots, characters, motives, and images of the three genres create the absorbing drama of an interlocking dialectic. To segregate these genres from one another is to miss, in all of them, half the story.