Overview

Aaron Reynolds delves into the relationship between peonage and the Alabama forests, exploring the history of post-slavery labor, the harsh conditions of labor camps, and the efforts of journalists and Department of Justice investigators to end the peonage system in the early twentieth century.

"Inside the Jackson Tract: The Battle Over Peonage Labor Camps in Southern Alabama, 1906" was selected for the Southern Spaces series "Landscapes and Ecologies of the US South," a collection of innovative, interdisciplinary publications about natural and built environments.

Introduction

|

| Location of Lockhart, Alabama, 2012. |

On a warm spring day in 1904, former governor of Maryland and lumberman E. E. Jackson, along with several associates, traveled to Alabama to view their extensive holdings of southern yellow pine forests. The party took a private train car owned by the president of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, Milton H. Smith, from Montgomery eighty miles south to Opp, the end of the line. American Lumberman wrote that the men spent two days "in the timber." Clad in fine suits and surrounded by industry journalists, they walked the forest and discussed plans to establish a "Model Sawmill Plant" and a company town named "Lockhart" after Standard Oil magnate, Charles Lockhart. The plan to transform this parcel of southern Alabama forest known as the "Jackson Tract" into a productive industrial operation drew investment capital from Pennsylvania and Baltimore, Maryland. Carrying out the strategy of the Jackson Lumber Company required transporting poorly provisioned European immigrant labor deep into forests to perform the brutal tasks of felling and hauling timber. Here a calculating labor manager, William S. Harlan, and sadistic foremen, Bob Gallagher and S. E. Huggins established a horrendous regime of forced labor that led to a physical and legal battle between managers, workers, and Progressive reformers.1"The Story of a Yellow Pine Sextet," American Lumberman 73 (March 5, 1904), 43; "Women Will Help in War Against Trusts," The New York Times, September 15, 1907.

Once inside the forest, workers confronted extreme temperatures, unsanitary provisions, and brutal labor bosses. Upon realizing the terrible conditions, many men attempted to escape from the Jackson camps. Documents in the Department of Justice (DOJ) Peonage Files as well as forest industry media and muckraker journalism reveal the social and environmental violence in the Jackson Tract. The struggle over lumber, peonage labor, and legal justice represents one narrative of progressive reform in the rural United States.2Mary Quackenbos affidavit, Department of Justice Files, National Archives, Record Group 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1 (Hereafter abbreviated "DOJ Files, NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1").

|

| Unidentified lumberman in the Jackson Tract, outside Lockhart, Alabama. American Lumberman 1907, Part 1, January–June 1907, Forest History Society archive. |

In the summer of 1906, one year after Theodore Roosevelt established the US Forest Service and appointed Gifford Pinchot to implement a conservationist policy, a conflict over workers rights and environmental conditions erupted inside the Jackson Company forests. The company claimed to base their Alabama operations on principles of forestry conservation and pronounced a commitment to bringing economic development to southern Alabama. Yet when officials in the DOJ received complaints from families of immigrant workers who went missing after taking forest industry jobs, a legal, intellectual, and physical battle ignited. Simultaneously, several immigrant workers, subjected to the forest's harsh environment and suffering abuse from violent woods bosses, defied the labor foremen and their bloodhounds, escaped into the woods, and eventually notified federal authorities. The men accused labor manager Harlan and his foremen of using the forested landscape to entrap laborers and conceal debt peonage and physical violence. In November, the DOJ prosecuted Harlan and several labor foremen for violating the Peonage Act of 1867, which outlawed forced labor as remuneration for debt. DOJ files relating to peonage investigations show how environmental and labor conditions inside the Jackson Tract contributed to conflict between workers, foremen, and federal deputies, and revealed the extent of peonage labor.3Ibid. The Peonage Files of the USDepartment of Justice reveal widespread systematic abuse of immigrant, African American, and white workers throughout the southern United States, particularly in rural industrial labor spaces where landscapes and the environment played a key role in violence between employers and workers. Many of the individual affidavits report the abuses and inhumane conditions workers experienced inside southern labor camps as well as foremen's collusion with local law enforcement to conceal their abuses from federal authorities. For a discussion of environmental history methodologies, see Gunther Peck, "The Nature of Labor: Fault Lines and Common Ground in Environmental and Labor History," Environmental History 11, no. 2 (April 2006): 212–38; William Cronon, "Modes of Prophecy and Production: Placing Nature in History," The Journal of American History 76, no. 4 (March 1990): 1122–31. For a discussion of Padrones and foreign contract labor in western industrial camps, see Gunther Peck, Reinventing Free Labor: Padrones and Immigrant Workers in the North American West, 1880–1930 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

|

| A log train with cut, stacked timber, near Lockhart, Alabama. American Lumberman 1907, Part 1, January–June 1907, Forest History Society archive. |

An examination of social and environmental violence in the Jackson Tract builds upon Karl Jacoby's call for further analyses of environment and wilderness in rural labor landscapes. Industrial elites' plans clashed with the resistance of workers in dangerous extractive industries. The remoteness of Jackson's labor camps hindered the federal government in exposing peonage abuses and protecting workers. An emphasis on workers' daily lives and landscape, which Mart A. Stewart defines as "a unit of [knowable] shaped land" reflecting "social and productive relationships," offers a method for examining nature and culture inside the Jackson Tract. Lumbermen, foremen, workers, and reformers generated a series of conflicts in this time of change in peonage labor regimes and rural extractive industries.4For a discussion of conflict over land use, see Karl Jacoby, Crimes Against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001); Mart A. Stewart, "What Nature Suffers to Groe": Life, Labor and Landscape on the Georgia Coast, 1680–1920 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1996), 1–2, 10, 12. For a discussion of industrialism in the "New South," see C. Vann Woodward, Origins of the New South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1951); Gavin Wright, Old South, New South: Revolutions in the Southern Economy Since the Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1986). For a discussion of labor exploitation and worker mobility, see Jacqueline Jones, The Dispossessed: America's Underclasses From the Civil War to the Present (New York: Basic Books, 1992).

The "Jackson Tract"

|

| E. E. Jackson. American Lumberman 1907, Part 1, January–June 1907, Forest History Society archive. |

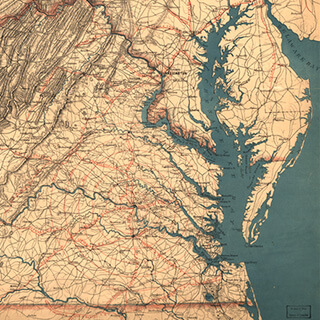

Governor E. E. Jackson of Maryland—Methodist, Republican, and "conservationist"—was born in Somerset, Maryland, in 1836. He grew up on his father's farm, acquired a modest education, and founded a country store near the town of Delmar. After the Civil War, Jackson established a flooring mill in Baltimore, which by 1870 was the leading business in the city. He bought a Washington, D.C factory that made hardwood flooring and cabinets for the housing boom of the 1880s. As a Gilded Age industrialist, Jackson expanded his lumber business through consolidation and vertical integration. In 1874, Jackson bought timber tracts in Nansemond County, Virginia, to supply his Baltimore and DC factories. There he built the first railroad in the South used exclusively for lumbering. Jackson purchased additional timber in Suffolk County, Virginia and in Gates County, North Carolina, near the Chowan River. As a political figure and entrepreneur, Jackson seized the opportunities found in the great southern forests.5American Lumbermen: The Personal History and Public and Business Achievements of One Hundred Eminent Lumbermen of the United States, vol. 3 (Chicago: American Lumbermen, 1906), 391, 393. On the rise of corporations nationally, see Alan Trachtenberg, The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Gilded Age (New York: Hill and Wang, 2007); Robert F. Himmelberg, ed., The Rise of Big Business and the Beginnings of Anti-trust and Railroad Regulation, 1870–1900 (New York: Garland Publishing, 1994).

Until the 1880s, northern and western dealers judged southern timber as weaker due to the warm climate. However, significant quantities of southern pine went into the construction of the 1892 Chicago World Fair, and by 1893, forty-one percent of the nation's softwood came from the South. The industry came to realize that southern timber was an enormous untapped resource. In 1900, Alabama contained over five thousand square miles of coniferous and deciduous forests referred to as "southern" or "yellow" pine. The ecological characteristics of the southern pine forests contributed to lumbermen's opportunistic dreams. Alabama's southwestern Pine Hills' climate offered hot summers and mild winters. Frequent fires kept underbrush down and regenerated the region's sandy soil.6Richard Walter Massey Jr., "A History of the Lumber Industry in Alabama and West Florida 1880–1914," (PhD diss., Vanderbilt University, 1960), 28–29. On the ecology of the southeastern Pine Hills, see Lawrence S. Earley, Looking for Longleaf: The Fall and Rise of an American Forest (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004). The northern belt of US coniferous pine forest stretches from New England through New York, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. The central pine belt begins at the Chesapeake Bay of Virginia and runs through North Carolina, northern Alabama, Mississippi, and Arkansas. The southern pine belt extends from southeastern Virginia to eastern Texas and includes shortleaf, loblolly, and slash pine, all of which were marketed as "southern" or "yellow pine." Southern forest industries provided timber and pitch tar to European markets beginning in the seventeenth century and by 1900 Chicago and the eastern United States consumed much of southern timber.

E. E. Jackson originally grew interested in Deep South forests in 1886, "backing his faith by extensive purchases" in Florida and Alabama. Primarily approaching forests as commodities, he administered the vast scale and scope of timber extraction through engineering, business consolidation, and labor control. Jackson believed that harvesting southern timber represented what Teddy Roosevelt called the "wise use" of forests, and claimed to operate his Alabama lumber industries "upon principles of forest conservation."7American Lumbermen, 391, 393.

Non-human nature played a central role in the transformation of landscapes, lumber, and labor inside the Jackson Tract. The company developed the town of Lockhart in a broad ecological zone of southern pine forests that covered nearly three-fifths of Alabama and Florida west of the Alapaha River. American Lumberman called the one billion feet of timber in the Jackson Tract "the finest body of yellow pine timber that ever grew in this country." The high and fairly level elevation of the tract lent itself to railroad construction and provided easy access to internal and foreign markets. The Lumberman boasted: "The fine and healthful climate and fertility of the soil will assist materially in making Lockhart an ideal industrial community."8"The Story of a Yellow Pine Sextet," 43, 45; F. V. Emerson, "The Southern Long-leaf Pine Belt," The Geographical Review 2 (January 1919), 81. For a general description of Alabama forests, see Roland M. Harper, Forests of Alabama (Tuscaloosa: Geological Survey Of Alabama, 1943). On southern economic development, see A. E. Parkins, The South, Its Economic-Geographic Development (New York: J. Wiley and Sons, 1938).

|

| The Jackson Plant, Lockhart, Alabama. American Lumberman 1907, Part 1, January–June 1907, Forest History Society archive. |

The Jackson Lumber Company portrayed the Lockhart operation as technological advancement and civilization brought to the underdeveloped southern Alabama forests. Lying one hundred miles south of Montgomery and eighty miles north of Pensacola, the company town of Lockhart mushroomed into a small industrial hub. Industry press promoted the operation's scope and sophistication, modern machinery, and mechanization of labor. American Lumberman reported: "Lockhart is as a sawmill town should be—in the woods—but it is [at] the very center of civilization." The Lockhart plant consisted of "two [saw] bands and a 48 inch gang [saw], with a capacity of 250,000 feet in a 22 hour run and will later be increased in size to have approximately that capacity in an 11 hour run, a planning mill equal to capacity as [the] saw mill, brick dry kilns with capacity of 160,000 feet powered by brick housed boiler plant of 72 inch by 18 foot boilers, 8 of these will be required for saw mill and dry kilns and 2 more for planning mill." Promising great profits for investors and sectional progress for the South, lumber journalists claimed Jackson offered "the provision of comfortable homes and pleasant surroundings, for the employees."9"Model Sawmill Plants, XXIII," American Lumberman 60 (November 10, 1900): 28–29. See also Massey, "A History of the Lumber Industry in Alabama and West Florida," 29. For discussion of the naval stores industry, see Robert Outland, Tapping the Pines: The Naval Stores Industry in the American South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004).

|

| Jackson Planning Mill, Lockhart, Alabama. American Lumberman 1907, Part 1, January–June 1907, Forest History Society archive. |

Industry media trumpeted Lockhart's operation to men of the professional class across the United States who envisioned investment or management-level employment opportunities with the Jackson Lumber Company. American Lumberman reported that the Lockhart operation produced "great quantities of comb-grained yellow pine flooring for shipment to fastidious New England. This product pleases the easterners so thoroughly well that they have not yet been able to get enough of it." The company's extraction of Alabama timber fit squarely within a larger pattern of what C. Vann Woodward called a "tributary economy" whereby northern and eastern capital invested in and exploited southern resources. Industry publications did not acknowledge the difficulty of transporting labor deep into the southern pine belt, nor the horrendous conditions workers faced in the forests outside Lockhart constructing railroads as well as cutting and hauling timber.10"Model Sawmill Plants, XXIII," 28–29; Woodward, Origins of the New South, 319.

|

| Jackson Sawmill, Lockhart, Alabama. Alexander Irvine, "My Life in Peonage," Appleton's Magazine, July 1907, 5. |

Railroads constituted the primary means of converting southern forest landscapes into rural industrial spaces. Railroad expansion increased demand for labor. Each mile of track required three thousand ties and an additional two hundred replacement ties per mile each year. Prior to 1900, most forest industry labor consisted of local, part-time tenant farmers who engaged in seasonal work on the railroads and in sawmills as a source of supplemental cash income or convict laborers which southern industrialists leased from the state penal system. Mark King, a local woodsman who lived in the area emphasized the danger, noting that "there was always the chance that a worker could be cut with a saw or an axe," and "even the most expert crews were not always certain of the direction a tree would fall." When trees crashed to the ground, limbs broke off and hurtled through the air in random and unpredictable directions. "On one occasion," King recalled, "a limb about the thickness of a man's arm hit the head of one of the cutters so hard that it killed him instantly and left a depression in his skull several inches deep."11Massey, "A History of the Lumber Industry in Alabama and West Florida," 35, 37.

Local white labor held better paying jobs in sawmill towns or seasonally cut and sold timber. Retaining labor in the forests far from the amenities of towns represented a perennial challenge to the company. In order to acquire workers where the available local and convict labor proved inadequate, industrialists involved in railroad construction and naval stores industries developed elaborate networks of peonage labor that involved trafficking workers, coercing their labor, and threatening criminal prosecution or even death if they attempted to flee. Scholars such as Pete Daniel, Jacqueline Jones, and Douglas Blackmon have shown that nearly one fourth of southern rural industrial workers were coerced through indebtedness or threat of physical violence. Men such as Henry Morrison Flagler of the Florida East coast Railroad, and Milton H. Smith of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad turned to foreign contract labor. The Jackson Lumber Company also recruited and transported foreign workers to its forest camps outside Lockhart.12Peonage labor is distinct from that in sawmill towns and locally owned turpentine camps where local and southern migrant labor dominated. For a discussion of convict and peonage labor, see Pete Daniel, The Shadow of Slavery: Peonage in the South, 1901–1969 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1972), especially 82–95; Jacqueline Jones, The Dispossessed: America's Underclasses from the Civil War to the Present (New York: Basic Books, 1992); Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York: Double Day, 2008).

Foreign Contract Labor

In the early 1900s, Jackson hired labor agents such as Sigmund Schwartz and Frank and Miller Company in New York City to recruit European immigrant laborers for the Jackson Tract. Foreign immigrant workers knew little of the dangers of forest industries, and recruiters lied to them about wages, fees for transportation, and conditions. The Jackson Lumber Company exploited thousands of foreign contract laborers and concealed its abusive practices. The company used peonage in both timber and naval stores. Federal investigators and muckraker journalists began to condemn the lumber industry for its exploitation of workers, wasteful practices, and laissez faire capitalism. Reformers sought to expose a "new slavery" in the US South, arguing that the 1867 Peonage Act prohibited any voluntary or involuntary servitude if retained through indebtedness or threat of violence. In 1906, Alexander Irvine, a writer for Appleton's Magazine, went undercover in the Jackson lumber camps. In My Life in Peonage, Irvine wrote that Lockhart was "a town where men were parts of machine—a machine to grind out profits for men who never saw the place, who never sensed its dull brutal life."13Massey, "A History of the Lumber Industry in Alabama and West Florida," 57–60; Mary Quakenbos affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1; Alexander Irvine, "My Life In Peonage: A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" Appleton's Magazine 10, no. 1 (July 1907): 14.

|

| Immigrant laborers, Greenwich Street, New York, New York. Alexander Irvine, "My Life in Peonage," Appleton's Magazine, August 1907, 193. |

|

| Laborers en route to the Jackson Tract, Atlantic Ocean. Alexander Irvine, "My Life in Peonage," Appleton's Magazine, August 1907, 190. |

The relationship between the Alabama forests and peonage labor began on the street corners of New York and Philadelphia where labor agents operated within networks of ethnic migration chains to exploit pools of unemployed immigrant workers. In 1906, the Jackson Lumber Company's expansion in Alabama led them to hire labor agent Sigmund S. Schwartz, who kept an office at First Street in Manhattan in the heart of the southern and eastern European immigrant neighborhoods. Along with recruiters such as Smith and Company, and Frank and Miller Company, Schwartz recruited thousands of workers for southern forest industry jobs. Jackson paid labor agents cash fees of three dollars for each man they sent to Lockhart. Workers became commoditized bodies to agents, or padrones, who directed them into labor trafficking networks. Agents recruited and transported workers of varying national origins to cities such as New York and Philadelphia and then on to the forests of Tennessee, Georgia, Florida, and Alabama.14Jacob Ormanskey affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. For more on immigration, ethnicity, and labor, see Matthew Frye Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999); Matthew Frye Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues: The United States Encounters Foreign Peoples at Home and Abroad, 1876–1917 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2000); Peck, Reinventing Free Labor.

Labor agents used two strategies in recruitment. First, they operated within immigrant populations experiencing high levels of unemployment and relied on social networks such as foreign language newspapers. Eugene P. Newlander, a Hungarian, worked for the Jackson Lumber Company as a labor agent and recruited workers from within the Hungarian population in New York City. Louis Kriger, a recent immigrant from Wilkomir, Russia, who had no family in the United States, was in New York a few months when he saw a newspaper advertisement for workers that directed him to the office of S. S. Schwartz. There, a man "with red hair, a German" told him there "was good work to be had in the South." Jacob Ormanskey was also recruited by Schwartz: "I left New York five weeks ago in company with about sixty men, fifteen of whom were Russian Jews, like myself."15Eugene P. Newlander, Louis Kriger, and Jacob Ormanskey affidavits, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1.

Labor recruiters lured workers, often from the rural hinterlands of eastern and southern Europe, with stories of easy labor in comfortable climates. Workers claimed Schwartz "told us good stories about work in the South," promising free transportation and one dollar and fifty cents per day. Schwartz told Harry Korshinsky that "he would be rapidly advanced" and that "it was a nice country and in all respects a splendid chance." "Joseph" (a Schwartz recruiter) lured Bennie Graubert, a Romanian, by describing the South as "nice country and easy work." He told him of a Georgia pencil factory. Another New York recruiter, the Frank and Miller Company, pledged skilled labor positions in Georgia and Alabama. They promised Rudolph Lanniger, a recent Russian immigrant, a "good job" and hired Manuel Jordomons, a Bulgarian, to do masonry work in Georgia.16Harry Korshinsky, Bennie Graubert, Rudolph Lanniger, and Manuel Jordomons affidavits, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. For a discussion of wilderness areas as spaces of opportunity and danger, see William Cronon, ed., Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature (New York: W. W. Norton, 1996).

|

| Box car quarters at a Jackson Company camp, outside Lockhart, Alabama. Alexander Irvine, "My Life in Peonage," Appleton's Magazine, July 1907, 3. |

|

| Inside the box car, outside Lockhart, Alabama. Alexander Irvine, "My Life in Peonage," Appleton's Magazine, July 1907, 6. |

In sworn affidavits taken by DOJ officials in 1906, immigrant workers linked the New York labor agents to the Jackson Company and described their trip to Georgia and Alabama as a forced crossing into a dangerous wilderness where severe conditions and racially charged labor regimes reduced them to chattel. Ormanskey testified that Smith and Company was "[a]n agent of the saw mill company . . . at Lockhart, Alabama" and reported that armed guards "brought us by steamer from New York to Savannah, where another agent of the company, a negro, met us and took us by train to Milner, Alabama. From there this negro, who was a foreman for Smith and Company, took us by wagon to Lockhart, about twenty miles from Milner." Frank and Miller shipped Rudolph Lanniger south to Savannah via steamship, then by rail to Lockhart. Ormanskey reported that many of the armed "negro" foremen, who took them from Savannah deep into the woods miles away from Lockhart, coerced workers and deterred escape attempts, initiating them into the violent social and environmental relationships that characterized peonage labor camps.17Jacob Ormanskey and Rudolph Lanniger affidavits, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1.

Armed guards took foreign workers to labor in what some described as complete wilderness. Others arrived at railroad construction sites with boxcar quarters. Workers described the conditions—a combination of intense heat, lack of provisions, and heavy timber—as "hell." Average temperatures for July through August reached over ninety degrees Fahrenheit and humidity levels consistently topped ninety percent. Direct, prolonged exposure to "the burning sun" caused serious physical injury to workers unaccustomed and unprotected. Alexander Irvine writes that after working in the hot sun for several days, Herman Ormanskey gained the sympathy of even some bosses because "the skin had peeled off his arms." Mike Trudics, a Hungarian, explained that as the foremen took him more than seven miles into the forest "a sort of dread seized me . . . I was filled with suspicion." Trudics explained to Irvine, "So here we were, out in a wild place, helpless and at the mercy of men who laughed at contracts and out of whose hip pockets bulged revolvers."18See Jesse Enloe, "Plot Time Series: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Climatic Data Center," last modified September 24, 2012, http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/temp-and-precip/time-series/; Harry Korshinsky affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1; Alexander Irvine, "My Life in Peonage: The Situation as I Found It," Appleton's Magazine 9, no. 6 (June 1907): 650; Mike Trudics, "Life Story of a Hungarian Peon," in Holt Hamilton, ed., The Life Stories of Undistinguished Americans as Told by Themselves (New York, NY: Routledge, 2000), 203–204.

"Treated like cattle"

Inside the Jackson tract, men worked alongside horses and mules, suffering the indignities and violence of chattel. In their reports to the DOJ, workers conflated the status of men and beasts. Edward J. Stone reported bosses forced him and other workers to carry two hundred pound railroad ties at gunpoint all day in the intense heat. John Gindes, a Slavic worker, testified, "The work was very hard and we were treated like cattle." When men refused, felt too weak to continue to work, or attempted escape, bosses and guards whipped them like oxen or beat them into submission. When a young boy named Joe ran into the forest, a foremen brought him back and bloodied his face with a shovel.19Harry Korshinsky, Jacob Ormanskey, Mike Trudics, Joseph Neil, and Louis Kriger affidavits, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1.

Labor foremen represented the primary threat to workers. Irvine depicts them as "ignorant, illiterate men" who "only know the law of the jungle." The woods' boss, S. E. Huggins, embodied the forest landscape. "Huggins is a typical frontiersman," writes Irvine. "He was probably born among the pines and inherited the knots. His face has the appearance of a turpentine tree newly chipped. It bears the marks of the shack." Irvine describes Huggins as tall and heavily built. "He shambles—usually with a cloud on his face and a chip on his shoulder. He understands the wild. He belongs there, and men who cannot easily adjust themselves to the life find little mercy or consideration at his hands. . . . A man who sells shoelaces on the bowery is not easily transformed into a lumber jack. Attempts to affect such a transformation brought into play the cowhide and the bloodhound."20Irvine, "The Situation as I Found It," 645, 647.

|

| Robert Gallagher. Alexander Irvine, "My Life in Peonage," Appleton's Magazine, June 1907, 646. |

Robert Gallagher, another Lockhart foreman, called by workers "the bull of the woods," routinely used debt peonage and physical brutality to coerce labor. Irvine describes Gallagher as an Irishman being only "a generation or two removed from the sod." He had a talent for profanity and was a "genius" as a labor driver. When the men requested to leave, Gallagher told them they owed the company for their transportation charges and could not go until they worked off the cost. He beat men who defied orders. He tied Manuel Jordomons, Harry Lyman, and John Cox to trees and pistol-whipped them for not cutting trees and carrying ties. He warned workers that if they tried to run, the "bloodhounds would finish them." Workers reported he regularly fired his pistol within inches of their faces, necks, and chests. Gallagher took a certain sadistic pleasure in abusing Herman Ormanskey, who the workers called "Square-head," beating him "on a daily basis."21Irvine, "A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" 3, 9; Manuel Jordomons affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1.

At the camps outside Lockhart where men cut railroad ties and timber for the lumber mill, Rudolph Lanniger reported, "There was no place to sleep," so he slept on the ground. Men reported being served cold, stale biscuits, twenty or so for roughly thirty men, "not enough to go around." A mile from the camp lay a "shallow ditch" that held the only available water supply. "I saw with my own eyes,” writes Irvine, “the excrement of both men and beasts dissolving in the ditch from which we got our drinking water." The men dug two wells, both of which produced "almost no water." The lack of sanitary water led to typhoid, causing suffering and killing at least two men in 1906.22Jacob Ormanskey, Rudolph Lanniger, and Manuel Jordamons affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1; Irvine, "A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" 10."

|

| The company's bloodhounds, outside Lockhart, Alabama. Alexander Irvine, "My Life in Peonage," Appleton's Magazine, July 1907, 7. |

Men and horses, mules, and oxen worked in teams cutting, loading, and hauling trees to the mill, confronting the dangers of heavy, freshly cut timber, flying splintered branches, and overloaded log trains. Animal strength was crucial to the lumbering process, and men acknowledged their dual status as men and beasts. Animals suffered the labor and injuries just as the men did. Timbering required extreme physical exertion, concentration, and quick reflexes. Small mistakes had deadly consequences. Fast moving log trains injured and killed horses, mules, dogs, and oxen, as well as cattle that wandered onto the tracks. Often companions of the workers, horses and dogs were also used to catch escapees.23Irvine, "A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" 8.

Giving voice to the public concern regarding an influx of foreigners and vagabond workers, the Florala News reported: "The company keeps trained dogs to run down such fellows as jump contracts and violate the laws." In testing a dog's capabilities, Gallagher once ordered an unsuspecting black guard into the woods on an errand and then sent the hounds after him. "They treed the nigger alright," noted the wife of foremen Archie Bellinger. Bloodhounds have thick coats and struggle in hot weather, easily overheating or even dying while in pursuit of escapees. They characteristically suffered from eye and skin infections and occasionally incurred injuries from heavy equipment. The cook, Hughie, had a "slew of pups" for pets and Irvine noted that one "ol' pup," named Nellie, was "cut in twain" by a logging train. Workers mourned Nellie's death, their tears revealing the attachment for their animal companions and the awkward similitude of men and animals in the camps.24Irvine, "The Situation As I Found It," 652; Bellinger quoted in Irvine, "A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" 8. For more on bloodhounds, see C. F. Brey and L. F. Reed, The Complete Bloodhound (Wiley, UK: Howell Book House, 1978); William D. Tolhurst, Manhunters: Hounds of the Big T (Louisville, KY: Hound Dog Press, 1984).

|

| Arthur Bellinger (left) and Alexander Irvine (second from left) with Larry the horse (far right), outside Lockhart, Alabama. Alexander Irvine, "My Life in Peonage," Appleton's Magazine, July 1907, 8. |

Irvine writes of a camp horse named Larry, driven excessively by the bosses until he became "so stupid that they could not work him. . . . The horse doctor said his mind was blank." Frustrated, Gallagher's assistant led Larry into the woods, then not unlike the men, beat him over the head with a tree branch, and left him bleeding for dead. Eventually, Larry regained consciousness and somehow returned to camp. Larry's story revealed the men's identification with the animals they worked alongside, as well as their dread of violence and their hope to survive.25Irvine, "A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" 6.

Despite the odds, men continually attempted escapes from the camps. "Hardly a day passed," Mike Trudics testified ". . . without some one being run down by the bosses or the bloodhounds and returned and whipped." This pattern characterized labor conflict in the Jackson Tract. Trudics arrived in Lockhart on July 18 and attempted to escape the next day. He "hid in the woods," but Gallagher eventually caught and whipped him. Jacob Ormanskey witnessed several men tied to trees and whipped for trying to get away. One John Dubrin attempted escape but was caught and locked in a "dark cellar" underground for three days. "In the woods," Trudics explained "they can do anything they want to and no one can see them but God."26Daniel, The Shadow of Slavery, 88; Jacob Ormanskey and Mike Trudics affidavits, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. On the legal history of the US South, see David J. Bodenhamer and James W. Ely, Jr. eds., Ambivalent Legacy: A Legal History of the South (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 1984), 70–100.

Gallagher did not catch every escaped worker. The same dense southern forests that concealed foremen's brutality aided runaways. Louis Kriger fled into the forest with seven other "boys" and immediately encountered another group of escaped workers. Emerging from the forest and seeing the foreman and a policeman, they ran the opposite direction into the woods. After hearing "some Irish men had run away before we came," said Bennie Graubert, "about twelve of us ran away too. . . . On the bridge we saw two carriages with sheriffs and bloodhounds. There were nine of us and we laid flat in the grass . . . for two hours." Eventually the men escaped through the swamps. The phrase "going to the woods" took on new meaning once inside the Jackson Tract.27Max Cantor, Louis Kriger, and Bennie Graubert affidavits, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1.

"A strange mixture"

The diversity of workers' ethnic and national background, combined with white foremen and local black labor, made the labor camps racially charged places. Witnesses did not acknowledge local white laborers inside the camps; however, some of them do appear in the record. Workers often traveled to, worked in, and ran off from the camps in ethnically homogenous groups, and their reports reveal ethnic and racial discrimination. Foremen's violence expressed labor hierarchies and white supremacist racial ideologies. Most Anglo Americans—north or south—did not consider immigrant workers from eastern and southern Europe to be "white." The remoteness and harsh environment facilitated the exploitation of foreign ethnic and southern black workers.28Louis Kriger affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. The literature on immigrants and race in the United States is vast. Some recommended books include John Higham, Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1955); Barbara Miller Solomon, Ancestors and Immigrants: A Changing New England Tradition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956); Donna Gabaccia, From Sicily to Elizabeth Street (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1984); Ewa Morawska, For Bread with Butter: The Life-Worlds of East Central European Immigrants in Johnstown, Pennsylvania 1890–1940 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1985); John Bodnar, The Transplanted: A History of Immigrants in Urban America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985); Elizabeth Ewen, Immigrant Women in the Land of Dollars: Life and Culture on the Lower East Side, 1890–1925 (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1985); Grace Elizabeth Hale, Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South 1890–1940, (New York: Pantheon Books, 1998); Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color; and Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues.

|

| Workers Nathan Scott, Manuel Jordoneff (also known as Jordomons), Michael Trudics, Arthur Buckley, and Herman Orminsky ("Square-head"), outside Lockhart, Alabama. Alexander Irvine, "My Life in Peonage," Appleton's Magazine, June 1907, 648. |

Ethnic difference was a major source of conflict. Men expressed prejudice even as most workers shared a similar condition in peonage. Irvine describes the camps as ethnically mixed but divisive, attributing the separations to both worker choice and southern custom. He notes that southern workers called the foreigners "dagos" and "sheenies." Men called one camp "the dago camp" for its large Italian element. Irvine points out the presence of separate quartering of workers and writes that the town of Lockhart was divided racially by "a small grove of pine trees" and had separate white and black schools and churches. Out in the forest camps, isolation facilitated some integration as well as violence among ethnically diverse laborers. Irvine describes his team as "a strange mixture—a Dane, a Virginia 'cracker,' a Michigan lumber jack, two Negroes, and an Irish man." The hierarchies that peonage labor regimes reinforced also generated conflict within ethnic groups. When one young Irish boy named McGuinnis refused to sleep in a train car with Greek workers, Gallagher, who expressed his ethnic pride by hanging Irish flags all around the camp, pistol-whipped the boy into submission.29Louis Kriger affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1; Irvine, "A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" 5, 9, 12, 13.

William P. Jones and David Oshinsky have pointed out that lumber camp and convict penal farm bosses often employed African American men—some of them also prisoners—to manage or guard other workers in southern rural labor camps. Though the town of Lockhart was strictly segregated, deep in the woods black guards held coercive power over ethnic European workers. The black foremen in the Jackson camps and "trusty shooters" on Mississippi's Parchman Farm represented modern counterparts to the black "drivers" of the antebellum plantation slave gangs. The presence of armed black guards made the camps particularly frightening to immigrant laborers, but their presence did not necessarily invert or challenge white supremacist codes. In the Jackson Tract, black foremen served under the command of the white bosses who paid them to coerce workers regardless of ethnic or racial categories. Workers testified that these "negroe guards" marched them from the trains into the forests. Jacob Ormanskey reported that when men were unable to work anymore, "the negro whipped us. He whipped me several times on my head, eyes, and back until I bled."30Jacob Ormanskey affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. On black lumber workers, see William P. Jones, The Tribe Of Black Ulysses: African American Lumber Workers In The Jim Crow South (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005). For more on penal farms, see David M. Oshinsky, Worse Than Slavery: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice (New York: Free Press, 1996). No personal affidavits of black guards exist in the records on the Lockhart camp.

|

| African American laborer chipping trees, outside Lockhart, Alabama. Forest History Society archive. |

The practice of de jure segregation drew Irvine's attention immediately upon entering Lockhart, but in the pine drifts he met and worked along side black teamster Bob Anderson. Gallagher repeatedly bailed Anderson out of jail for drunkenness and added the cost to his contract, a familiar peonage tactic. Though workers of different races and ethnicities lived and labored together, black workers suffered especially violent treatment at the hands of white bosses. Irvine reportd that Gallagher instigated one of the most humiliating creations of the Jim Crow South, the "battle royale," where whites force black men to fight each other, often to the death, not unlike cocks, or dogs. At least once, Gallagher gave two black workers metal pipes and coerced them at gunpoint to fight. He broke the fight up only after the two men bloodied one another severely.31Irvine, "A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" 5, 9; Louis Kriger affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1.

Irvine describes the camps in terms of white racism that labeled African Americans as ignorant and crude while overlooking their resistance strategies. In "the negro car" he encountered "half a dozen men . . . having a card game," and a "group of singers around a banjo. . . . The financial losses of the singers added color to the words of the song." From its inception, the blues dealt with toil and oppression. Barrelhouse, country, and blues music served as emotional release and oppositional expression. Even as Irvine exposes black suffering, he awkwardly expresses their situation as victimized laborers and symbols of social disorder.32Irvine, "A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" 12. On African American resistance strategies, see Robin D. G. Kelley, "'We Are Not What We Seem': Rethinking Black Working-Class Opposition in the Jim Crow South," The Journal Of American History 80, no. 1 (June, 1993): 75–112. See also James C. Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990).

Irvine offers evidence of whites' perception of their fellow black workers. Noting that the white men spoke of "'nigger's' inferiority," he adds that ". . . the 'nigger' was doing the best work in camp." Irvine reinforces notions of black workers as crude when he writes that the particularly "smutty stories" whites told "would make [even] a negro blush." Black workers' role in the camps embodied their crucial position in the labor regime, where whites perceived them as crude and peculiar and as victims of or threats to the social order.33Irvine, "A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" 9.

Progressive Reformers

Mary Grace Quackenbos earned a reputation as an attorney who aided poor and immigrant laborers in New York City against the abuses of employers and factory owners. In 1906 she traveled to Florida and Alabama after receiving complaints from families of immigrant workers that several of their young men were missing. Assistant US attorney general Charles Wells Russell supported Quackenbos, appointed her as his special assistant, and encouraged her campaign to expose peonage in southern rural industries. She first attended to complaints from workers in railroad and turpentine camps at Buffalo Bluff and Maytown in northeast Florida. Quackenbos targeted Sigmund Schwartz and foreman William S. Harlan, linking their brutality toward workers to the Jackson Lumber Company. Reformers identified immigrants as victims of recruiters' deceptive practices and documented how Harlan and Gallagher indebted and coerced workers inside the Jackson camps.34Mary Quackenbos affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. On peonage trials, see Daniel, The Shadow of Slavery. On Quackenbos, see Jerrell H. Shofner, "Mary Grace Quackenbos, a Visitor Florida Did Not Want," Florida Historical Quarterly 58, no. 3 (January 1980): 273–290; Randolf H. Boehm, "Mary Grace Quackenbos and the Federal Campaign against Peonage: The Case of Sunnyside Plantation," The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 50, no. 1 (Spring 1991): 40–59.

|

| William S. Harlan. American Lumberman 1907, Part 1, January–June 1907, Forest History Society archive. |

Exposing company abuses and proving that foremen held workers against their will required reformers to visit the camps. Quackenbos wrote that the "cruelties practiced" were "not easy to get at . . . unless detectives could spend many weeks in those camps and subject themselves to the dangers." The first federal investigators to visit the northern Florida camps faced swarms of mosquitoes, traversed swamps, and found the forests "infested with wild animals of all kinds, snakes, alligators, and other reptiles." Investigators agreed that the physical environment contained significant dangers to workers' health, provided obstacles preventing their escape, and that employers intentionally used islands, swamps, and forests to retain labor. Rejecting claims that formen carried shotguns to defend against the "wild panthers," investigators wrote that laborers "are through the natural circumstances and conditions held in abject slavery." They utilized vivid descriptions of the tract to make their case against the Jackson Lumber Company.35Mary Quackenbos and Will Nanse affidavits, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. On Progressivism in general, see Michael E. McGerr A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America, 1870–1920, (New York: Free Press, 2003).

Will Nanse traveled to Lockhart in August 1906 in service of the DOJ and immediately witnessed the violent conflict between workers and bosses. He saw Gallagher shoot at a black worker named John. Nance said John "had been working and had quit," then attempted to leave the camp on a logging car. Gallagher threatened, "I'll whip you" to which John replied, "No, you'll have to kill me, I won't go to be whipped." "I'll kill you" Gallagher replied, and fired his pistol three times. John fled through the woods with Gallagher giving chase, firing his pistol "at least a dozen times." It's unclear whether Gallagher killed John or if he escaped.36Will Nanse affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1.

![Some of the [Jackson] company's executives, including Bob Gallagher (right), outside Lockhart, Alabama. Alexander Irvine, "My Life in Peonage," Appleton's Magazine, June 1907, 4. Some of the [Jackson] company's executives, including Bob Gallagher (right), outside Lockhart, Alabama. Alexander Irvine, "My Life in Peonage," Appleton's Magazine, June 1907, 4.](https://i0.wp.com/southernspaces.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/014-ss-12-reynol_sm.jpg?resize=300%2C336&ssl=1) |

| Some of the [Jackson] company's executives, including Bob Gallagher (right), outside Lockhart, Alabama. Alexander Irvine, "My Life in Peonage," Appleton's Magazine, June 1907, 4. |

Deep South lumbermen and state officials colluded with immigration agents to conceal labor abuses while promoting the development of rural industries and encouraging foreign workers. At Quckenbos' request, Gerold Rolfs, the German consul at Pensacola, sent Emile Lesser, president of the German Immigration Society and the United Hebrew Charities to inquire into reports of workers being retained against their will inside the Jackson Tract. Lesser reported that Rolfs told him "any conviction for peonage would materially hurt Southern Immigration" by restricting the flow of workers to the camps. The company doctor escorted Lesser to the Jackson camp where he met several German workers. Lesser testified that Rolfs ordered him to say that "no peonage existed there" and that "I did so." Will Nanse reported that Harlan and Huggins removed workers who might attest to abuses. Gallagher "spirited away" Buckley and Ormanskey "to a camp in the woods [where] they were kept out of sight." The company took them to Pensacola to avoid being interviewed.37Nance and Lesser quoted in DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1; Irvine, "The Situation as I Found It," 650.

Lesser acknowledged that Gallagher was a "brute" but stated that he personally favored the "increase of German immigration to the South," as it "was a good cause and that the state should endorse the opening of an immigration office abroad to direct European immigrants to the South." He insisted that any letter attesting to peonage in Lockhart "would not hurt the company" unless, as US attorney Sheppard told him, "it was proved that the [Jackson Lumber] company authorized Gallagher's abuses." Lesser's testimony was crucial to the investigation into the company's operations. Along with Will Nanse's affidavit, it confirmed Quackenbos's assertion that Harlan, Huggins, and Gallagher used the forest to retain workers and prevent the exposure of brutality.38Mary Quackenbos and Will Nanse affidavits, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1.

Quackenbos, Nanse, and the other DOJ investigators compiled significant evidence of labor abuses in the Jackson Tract. Along with Irvine's reporting, progressive reformers revealed the exploitative character of foreign contract labor. In regards to the Harlan case, the New York Times reported that "Miss Grace Winterton, [Quackenbos] compiled a mass of evidence which was so startling in its truth and proof that Assistant [US] Attorney General Charles W. Russell was immediately designated by the government to begin an exhaustive prosecution." Quackenbos successfully prosecuted Harlan in a contest that reached the attention of President Roosevelt. Yet lumbermen in Florida and Alabama appealed the case, delaying penalties on Harlan and Huggins. In a gesture meant to appease southern employers and local authorities while giving a nod to federal prosecutors, President Taft agreed to "commute the sentences of Harlan, Huggins, and Hilton" but only after they "surrendered to accept the action of the court." The Jackson Lumber Company attorneys defied the courts by filing "habeas corpus writs" until the US Supreme Court ruled in favor of the DOJ's prosecution in November 1910.39Mary Quackenbos affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1; "Woman Will Help in War Against Trusts; Mrs. Quackenbos, Attorney General's Assistant, a Lawyer and Member of Old New York Family," The New York Times, September 15, 1907.

Alabama lumbermen used their political leverage to influence Booker T. Washington to write a letter on behalf of Harlan to President Taft, defending him because he consistently employed black workers. "There are few men anywhere in the South," Washington wrote, "who have stood higher than Mr. Harlan or have done more for the development of the South." Washington, concerned as he was with the abuse of African American laborers, sought to maintain favor with southern lumbermen. Like penal reform movements that touted the social and economic advantages of the convict lease system, foreign contract labor represented another example of business and political elites' attempt to develop the South by trafficking and exploiting marginalized workers. Even after the convictions of Harlan and O'Hara and the success of the 1911 Alonzo Bailey case that outlawed forced labor in remuneration of personal debt, political compromise between federal elected officials and southern state and local governments systematically concealed peonage labor abuses on private farms, turpentine camps, and corporate fruit and vegetable farms throughout the interwar years and beyond.40Daniel, Shadow of Slavery, 90–93; Mary Quackenbos affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1.

About the Author

Aaron Reynolds is a PhD candidate at University of Texas, Austin preparing to graduate in Spring 2013. Born and raised in central Texas, his scholarly interests include labor and environment in the US South. He thanks the editors and staff at Southern Spaces for their support, as well as Dr. Jacqueline Jones, and the Forest History Society at Duke University for their help with his research and writing of "The Jackson Tract."

Recommended Resources

Blackmon, Douglas A. Slavery by Another Name. New York City: Doubleday, 2008.

Earley, Lawrence S. Looking for Longleaf: The Fall and Rise of an American Forest. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Hatley, Tom. "Forestry and Equity." Southern Changes 5, no. 4 (1983). http://beck.library.emory.edu/southernchanges/article.php?id=sc05-4_007.

Irvine, Alexander. "My Life In Peonage: The Situation as I Found It." Appleton's Magazine 9, no. 6 (June 1907): 643–654.

———. "My Life In Peonage: A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods.'" Appleton's Magazine 10, no. 1 (July, 1907): 3–15.

———. "My Life In Peonage: The Kidnapping of 'Punk.'" Appleton's Magazine 10, no. 2 (August, 1907): 190–197.

Jacoby, Karl. Crimes Against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

Jones, Will. The Tribe of Black Ulysses: African American Lumber Workers in the Jim Crow South. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Massey, Richard Walter. "A History of the Lumber Industry in Alabama and West Florida 1880–1914." PhD diss., Vanderbilt University, 1960.

Outland, Robert. Tapping the Pines: The Naval Stores Industry in the American South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004.

Video

Slavery by Another Name. Directed by Sam Pollard. PBS. (2012; Twin Cities Public Television), online. http://www.pbs.org/tpt/slavery-by-another-name/watch/.

Links

Peonage Files of the US Department of Justice, 1901–1945, Fondren Library, Rice University

http://library.rice.edu/collections/folder.2008-11-20.5288410834/peonage-files-of-the-u-s-department-of-justice-1901-1945.

Forest History Society

http://www.foresthistory.org.

Similar Publications

| 1. | "The Story of a Yellow Pine Sextet," American Lumberman 73 (March 5, 1904), 43; "Women Will Help in War Against Trusts," The New York Times, September 15, 1907. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Mary Quackenbos affidavit, Department of Justice Files, National Archives, Record Group 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1 (Hereafter abbreviated "DOJ Files, NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1"). |

| 3. | Ibid. The Peonage Files of the USDepartment of Justice reveal widespread systematic abuse of immigrant, African American, and white workers throughout the southern United States, particularly in rural industrial labor spaces where landscapes and the environment played a key role in violence between employers and workers. Many of the individual affidavits report the abuses and inhumane conditions workers experienced inside southern labor camps as well as foremen's collusion with local law enforcement to conceal their abuses from federal authorities. For a discussion of environmental history methodologies, see Gunther Peck, "The Nature of Labor: Fault Lines and Common Ground in Environmental and Labor History," Environmental History 11, no. 2 (April 2006): 212–38; William Cronon, "Modes of Prophecy and Production: Placing Nature in History," The Journal of American History 76, no. 4 (March 1990): 1122–31. For a discussion of Padrones and foreign contract labor in western industrial camps, see Gunther Peck, Reinventing Free Labor: Padrones and Immigrant Workers in the North American West, 1880–1930 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000). |

| 4. | For a discussion of conflict over land use, see Karl Jacoby, Crimes Against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001); Mart A. Stewart, "What Nature Suffers to Groe": Life, Labor and Landscape on the Georgia Coast, 1680–1920 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1996), 1–2, 10, 12. For a discussion of industrialism in the "New South," see C. Vann Woodward, Origins of the New South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1951); Gavin Wright, Old South, New South: Revolutions in the Southern Economy Since the Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1986). For a discussion of labor exploitation and worker mobility, see Jacqueline Jones, The Dispossessed: America's Underclasses From the Civil War to the Present (New York: Basic Books, 1992). |

| 5. | American Lumbermen: The Personal History and Public and Business Achievements of One Hundred Eminent Lumbermen of the United States, vol. 3 (Chicago: American Lumbermen, 1906), 391, 393. On the rise of corporations nationally, see Alan Trachtenberg, The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Gilded Age (New York: Hill and Wang, 2007); Robert F. Himmelberg, ed., The Rise of Big Business and the Beginnings of Anti-trust and Railroad Regulation, 1870–1900 (New York: Garland Publishing, 1994). |

| 6. | Richard Walter Massey Jr., "A History of the Lumber Industry in Alabama and West Florida 1880–1914," (PhD diss., Vanderbilt University, 1960), 28–29. On the ecology of the southeastern Pine Hills, see Lawrence S. Earley, Looking for Longleaf: The Fall and Rise of an American Forest (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004). The northern belt of US coniferous pine forest stretches from New England through New York, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. The central pine belt begins at the Chesapeake Bay of Virginia and runs through North Carolina, northern Alabama, Mississippi, and Arkansas. The southern pine belt extends from southeastern Virginia to eastern Texas and includes shortleaf, loblolly, and slash pine, all of which were marketed as "southern" or "yellow pine." Southern forest industries provided timber and pitch tar to European markets beginning in the seventeenth century and by 1900 Chicago and the eastern United States consumed much of southern timber. |

| 7. | American Lumbermen, 391, 393. |

| 8. | "The Story of a Yellow Pine Sextet," 43, 45; F. V. Emerson, "The Southern Long-leaf Pine Belt," The Geographical Review 2 (January 1919), 81. For a general description of Alabama forests, see Roland M. Harper, Forests of Alabama (Tuscaloosa: Geological Survey Of Alabama, 1943). On southern economic development, see A. E. Parkins, The South, Its Economic-Geographic Development (New York: J. Wiley and Sons, 1938). |

| 9. | "Model Sawmill Plants, XXIII," American Lumberman 60 (November 10, 1900): 28–29. See also Massey, "A History of the Lumber Industry in Alabama and West Florida," 29. For discussion of the naval stores industry, see Robert Outland, Tapping the Pines: The Naval Stores Industry in the American South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004). |

| 10. | "Model Sawmill Plants, XXIII," 28–29; Woodward, Origins of the New South, 319. |

| 11. | Massey, "A History of the Lumber Industry in Alabama and West Florida," 35, 37. |

| 12. | Peonage labor is distinct from that in sawmill towns and locally owned turpentine camps where local and southern migrant labor dominated. For a discussion of convict and peonage labor, see Pete Daniel, The Shadow of Slavery: Peonage in the South, 1901–1969 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1972), especially 82–95; Jacqueline Jones, The Dispossessed: America's Underclasses from the Civil War to the Present (New York: Basic Books, 1992); Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York: Double Day, 2008). |

| 13. | Massey, "A History of the Lumber Industry in Alabama and West Florida," 57–60; Mary Quakenbos affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1; Alexander Irvine, "My Life In Peonage: A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" Appleton's Magazine 10, no. 1 (July 1907): 14. |

| 14. | Jacob Ormanskey affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. For more on immigration, ethnicity, and labor, see Matthew Frye Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999); Matthew Frye Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues: The United States Encounters Foreign Peoples at Home and Abroad, 1876–1917 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2000); Peck, Reinventing Free Labor. |

| 15. | Eugene P. Newlander, Louis Kriger, and Jacob Ormanskey affidavits, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. |

| 16. | Harry Korshinsky, Bennie Graubert, Rudolph Lanniger, and Manuel Jordomons affidavits, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. For a discussion of wilderness areas as spaces of opportunity and danger, see William Cronon, ed., Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature (New York: W. W. Norton, 1996). |

| 17. | Jacob Ormanskey and Rudolph Lanniger affidavits, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. |

| 18. | See Jesse Enloe, "Plot Time Series: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Climatic Data Center," last modified September 24, 2012, http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/temp-and-precip/time-series/; Harry Korshinsky affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1; Alexander Irvine, "My Life in Peonage: The Situation as I Found It," Appleton's Magazine 9, no. 6 (June 1907): 650; Mike Trudics, "Life Story of a Hungarian Peon," in Holt Hamilton, ed., The Life Stories of Undistinguished Americans as Told by Themselves (New York, NY: Routledge, 2000), 203–204. |

| 19. | Harry Korshinsky, Jacob Ormanskey, Mike Trudics, Joseph Neil, and Louis Kriger affidavits, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. |

| 20. | Irvine, "The Situation as I Found It," 645, 647. |

| 21. | Irvine, "A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" 3, 9; Manuel Jordomons affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. |

| 22. | Jacob Ormanskey, Rudolph Lanniger, and Manuel Jordamons affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1; Irvine, "A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" 10." |

| 23. | Irvine, "A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" 8. |

| 24. | Irvine, "The Situation As I Found It," 652; Bellinger quoted in Irvine, "A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" 8. For more on bloodhounds, see C. F. Brey and L. F. Reed, The Complete Bloodhound (Wiley, UK: Howell Book House, 1978); William D. Tolhurst, Manhunters: Hounds of the Big T (Louisville, KY: Hound Dog Press, 1984). |

| 25. | Irvine, "A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" 6. |

| 26. | Daniel, The Shadow of Slavery, 88; Jacob Ormanskey and Mike Trudics affidavits, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. On the legal history of the US South, see David J. Bodenhamer and James W. Ely, Jr. eds., Ambivalent Legacy: A Legal History of the South (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 1984), 70–100. |

| 27. | Max Cantor, Louis Kriger, and Bennie Graubert affidavits, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. |

| 28. | Louis Kriger affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. The literature on immigrants and race in the United States is vast. Some recommended books include John Higham, Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1955); Barbara Miller Solomon, Ancestors and Immigrants: A Changing New England Tradition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956); Donna Gabaccia, From Sicily to Elizabeth Street (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1984); Ewa Morawska, For Bread with Butter: The Life-Worlds of East Central European Immigrants in Johnstown, Pennsylvania 1890–1940 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1985); John Bodnar, The Transplanted: A History of Immigrants in Urban America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985); Elizabeth Ewen, Immigrant Women in the Land of Dollars: Life and Culture on the Lower East Side, 1890–1925 (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1985); Grace Elizabeth Hale, Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South 1890–1940, (New York: Pantheon Books, 1998); Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color; and Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues. |

| 29. | Louis Kriger affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1; Irvine, "A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" 5, 9, 12, 13. |

| 30. | Jacob Ormanskey affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. On black lumber workers, see William P. Jones, The Tribe Of Black Ulysses: African American Lumber Workers In The Jim Crow South (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005). For more on penal farms, see David M. Oshinsky, Worse Than Slavery: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice (New York: Free Press, 1996). No personal affidavits of black guards exist in the records on the Lockhart camp. |

| 31. | Irvine, "A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" 5, 9; Louis Kriger affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. |

| 32. | Irvine, "A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" 12. On African American resistance strategies, see Robin D. G. Kelley, "'We Are Not What We Seem': Rethinking Black Working-Class Opposition in the Jim Crow South," The Journal Of American History 80, no. 1 (June, 1993): 75–112. See also James C. Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990). |

| 33. | Irvine, "A Week with the 'Bull of the Woods,'" 9. |

| 34. | Mary Quackenbos affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. On peonage trials, see Daniel, The Shadow of Slavery. On Quackenbos, see Jerrell H. Shofner, "Mary Grace Quackenbos, a Visitor Florida Did Not Want," Florida Historical Quarterly 58, no. 3 (January 1980): 273–290; Randolf H. Boehm, "Mary Grace Quackenbos and the Federal Campaign against Peonage: The Case of Sunnyside Plantation," The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 50, no. 1 (Spring 1991): 40–59. |

| 35. | Mary Quackenbos and Will Nanse affidavits, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. On Progressivism in general, see Michael E. McGerr A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America, 1870–1920, (New York: Free Press, 2003). |

| 36. | Will Nanse affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. |

| 37. | Nance and Lesser quoted in DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1; Irvine, "The Situation as I Found It," 650. |

| 38. | Mary Quackenbos and Will Nanse affidavits, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. |

| 39. | Mary Quackenbos affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1; "Woman Will Help in War Against Trusts; Mrs. Quackenbos, Attorney General's Assistant, a Lawyer and Member of Old New York Family," The New York Times, September 15, 1907. |

| 40. | Daniel, Shadow of Slavery, 90–93; Mary Quackenbos affidavit, DOJ Files NA, RG 60, Class 50, Box 10800, File 50-162-1. |