Overview

|

| George Harper Houghton, Family of slaves at the Gaines' house, Hampton, Virginia, c. 1861. Courtesy the Library of Congress. |

In this essay, Scott Nesbit analyzes migration and marriage patterns of recently freed men and women in post-Emancipation Virginia. Nesbit shows how slaves developed different concepts of marriage in response to forced internal migration, and then later, how recently freed men and women used governmental agents, employers, and even former slaveholders to buttress their legal claims to their families. The essay offers an interactive map that organizes migration and marriage data of former slaves from counties across Virginia.

"Scales Intimate and Sprawling: Slavery, Emancipation, and the Geography of Marriage in Virginia" was selected for the 2010 Southern Spaces series "Migration, Mobility, Exchange, and the U.S. South," a collection of innovative, interdisciplinary scholarship about how the movements of individuals, populations, goods, and ideas shape dynamic spaces, cultures, and identities within or in circulation with the US South.

Introduction

Peggy Winn had every reason to believe freedom meant stability for her family, stability in a new place. Under slavery, she had lived in the southern section of Albemarle County, Virginia, on the Cleveland farm. Winn had been born in the same county and avoided the most devastating effects of the slave trade: the sale away from kin. She married Benjamin Barbour when she was twenty, around 1845. Barbour was born in Greene County, just to the north of Albemarle, too far to see her frequently. Either through the local hiring system, slave trade, or other means, he managed to move—or was moved—close enough to Peggy that they could visit, often enough that Peggy's owner and his felt comfortable assenting to the marriage. When, nearly twenty years later, they registered their marriage with Freedmen's Bureau agents in Augusta County, just to the west of Albemarle, they found more stability for their marriage and their two young girls, Mariah and Corra, than was possible before. Emancipation and state recognition of the family removed the principle geographic threat of slavery: forced separation through the slave trade.1Register of Colored Persons of Augusta County, State of Virginia, Cohabiting Together as Husband and Wife, 1866 Feb. 27 (hereafter Cohabitation Register, Augusta County), 28. Cohabitation Registers Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, http://digitool1.lva.lib.va.us:8881/R?func=collections-result&collection_id=1522; U.S. Bureau of the Census, Eighth Census of the United States, 1860. Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, 1860, M653, 1,438 rolls, source consulted: s.v. P. Cleveland, 1860 United States Federal Census, Slave Schedules, Albemarle County, Virginia, http://www.ancestry.com/; P. Cleveland to [Thomas P. Jackson], May 6, 1867, Valley of the Shadow: Two Communities in the American Civil War online, http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/papers/B0193, source copy available as National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (hereafter hereafter NARA BRFAL), Record Group 105, Box E4269; 1870 U.S. Federal Census, http://ancestry.com/ s.v. Benjamin Barbourn [Barbour], District 3, Augusta, Virginia, M593_1634, page 370B.

Yet sustaining a marriage in a new place with this new status brought challenges. By April 1867, a year after Winn and Barbour registered, they found their relationship the focus of a concerted attack. Since Freedom, Winn lived and worked at the home of Urban Poe, an Augusta County merchant and local political operative. Poe had no interest in Winn continuing her marriage to Barbour, so he forbade the freedman from trespassing on his property and shot at him when he did. Poe brought Barbour before the Freedmen's Court, arguing that Barbour had "slandered his character" by representing that Poe was "living with Barber's wife," when in actuality, Poe argued, "he is no count to her or her children & She wants to leave him." Poe lined up neighbors to bolster his case: the wealthy farmer Robert Van Lear was prepared to support Poe's claim against Barbour, as was Mrs. Henry Palmer. Fortunately for Winn and Barbour, other whites were willing to testify to their longstanding relationship. Contacted by Barbour and by Poe to serve as a witness, Winn's former owner wrote to the local Freedmen's Bureau agent, interceding on Barbour's behalf. The agent quickly dismissed Poe's case.2Valley Virginian, February 21, 1866, p. 3 col. 2, Valley of the Shadow online, http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/news/vv1866/va.au.vv.1866.02.21.xml#03; U.D. Poe to P.P. Cleveland, April 30, 1867, Valley of the Shadow online, http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/papers/B0192 source available NARA BRFAL, RG 105; P. Cleveland to [Thomas P. Jackson], May 6, 1867, Valley of the Shadow online; 1860 U.S. Federal Census, Agriculture Schedule, http://www.ancestry.com/ s.v. Robt Van Lear, Augusta County, Virginia, roll 5, p. 273; Augusta County: Freedmen's Bureau Register of Complaints, May 8, 1866, Valley of the Shadow online, http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/papers/BD4000, source available, NARA BRFAL, RG 105, Box E4237.

|

| Augusta County Cohabitation Register, page 28. Benjamin Barbour and Peggy Winn were two of fifteen hundred men and women in Augusta County who registered their marriage with the Freedmen's Bureau in 1866. Courtesy the Library of Virginia. |

Winn and Barbour made a place for their marriage in defiance of the slave trade, under constraints to their mobility, and by taking advantage of the postwar government's intervention into black marriage. They met, married, and against odds sustained their relationship for over fifteen years in a Virginia Piedmont wracked by displacement caused by the slave trade and forced removal. They strained against the distance which slavery imposed and innovated, as many others did, by "living abroad" on different farms. Even after emancipation Winn and Barbour continued to live at a distance, but freedom significantly lowered the barriers to living under the same roof and altered the meaning and experience of the same intervals. The couple used federal, state, and local bureaucracies, which imposed a legal structure for marriage on existing relationships that fit poorly with the diversity of living arrangements men and women had taken on, but provided safeguards for African American families, expansive networks to help freedmen repair relationships, and means for black men and women to defend their families in court.

Emancipation-era marriages were enacted over time and at multiple interrelated scales of action, from the level of the plantation household and neighborhood to that of the interstate slave trade and federal bureaucracy. We need to consider all of these levels together to perceive the connections and describe the reach of human actions and practices. The scales at which women and men acted extend from the private sphere to institutions or networks. Attention to scale can sort out actions of local Bureau officials, state legislators, and radicals in Congress while clarifying more complex relations. Men and women whom we often consider to be household actors also engaged in processes and networks that spanned the US South.3Geographers have disagreed about many aspects of the definition of scale. See Peter Taylor, "A Materialist Framework for Political Geography," Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, n.s., 7, no. 1 (1982): 15-34; Neil Smith, Uneven Development: Nature, Capital, and the Production of Space (Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell, 1984); Sallie A. Marston, "The Social Construction of Scale" Progress in Human Geography 24, no. 2 (2000): 219-242; Andrew E. G. Jonas, "Pro Scale: Further Reflections on the 'Scale Debate' in Human Geography," Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, n.s., 31, no. 3 (2006): 399-406; and Edward L. Ayers and Scott Nesbit, "Seeing Emancipation: Scale and Freedom in the American South," Journal of the Civil War Era 1, no. 1 (2011): 3-22.

Formerly enslaved men and women were constantly acting within networks—kinship relations, social hierarchies, labor markets, and bureaucracies—of particular reach, at particular scales, to find whatever stability and autonomy they could for their families. Because these networks often connected local affairs with far-flung places and broad structures of political and economic power, freedwomen and men built marriages both through the quotidian, household practices of love and labor and by leveraging bureaucracies and labor markets. Emancipation-era marriages built intimate bonds and sprawling connections. Marriage muddied the spatial boundaries between fictive emancipation-era private and public spheres.

At the most intimate scale, a wide diversity of living arrangements fell under the single legal framework of emancipation marriage. These arrangements were in part a product of new legal guarantees for marriages of freedpeople, in part the product of relationships given shape under slavery and menaced by the slave market. This market created staggering obstacles: enslaved marriages had endured the large-scale transport of people from the Virginia Piedmont and Tidewater to the antebellum Southwest, as well as significant but more intricate movements, such as those that brought more than one-hundred fifty men and women from Albemarle to Augusta, or movements from north and west that brought hundreds of others to long-settled Hanover County. The legal framework for emancipation-era marriage, which generated the records through which we can know something of those migrations, emerged out of unusual cooperative action between multiple levels of government: conservative state legislatures, local governments controlled by former Confederates, and the United States Bureau for Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands. This legal framework and the government agents who carried it out had a direct effect on the chances of enslaved men and women to reunite across hundreds of miles.4For scholarship on African American families at these and other scales, see Thavolia Glymph, Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008); Anthony Kaye, Joining Places: Slave Neighborhoods in the Old South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007); Brenda Stevenson, Life in Black and White: Family and Community in the Slave South (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997); Laura Edwards, Gendered Strife and Confusion: The Political Culture of Reconstruction (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1997); Wilma A. Dunaway, The African American Family in Slavery and Emancipation (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003); Jacqueline Jones, Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family from Slavery to the Present (New York: Basic Books, 1985); Amy Dru Stanley, From Bondage to Contract: Wage Labor, Marriage, and the Marketplace in the Age of Slave Emancipation (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998); Peter Bardaglio, Reconstructing the Household: Families, Sex, and Law in the Nineteenth-Century South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995); Mary Farmer-Kaiser, Freedwomen and the Freedmen's Bureau: Race, Gender, and Public Policy in the Age of Emancipation (New York: Fordham University Press, 2010); recent investigations of families' transition to emancipation build on an earlier historiographical debate: E. Franklin Frazier, The Negro Family in the United States (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1939); Daniel P. Moynihan, The Negro Family: The Case for National Action (Washington, DC: Office of Policy Planning and Research, U.S. Department of Labor, 1965); John W. Blassingame, The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972); and Herbert G. Gutman, The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750-1925 (New York: Pantheon, 1976).

Defining Legal Status

Formalization of marriages between enslaved men and women was a cause for concern among those working at the highest governmental levels long before Freedmen's Bureau agents arrived to take down names in Augusta County, Virginia. In early 1864, as black Kentuckians enlisted in the US Army in increasingly large numbers, Sen. Henry Wilson of Massachussetts proposed a bill setting free women held in bondage there by loyal owners, by virtue of their marriage to United States Colored Troops enlistees. The resulting law, as Amy Dru Stanley has pointed out, was problematic for entwining women's freedom with marriage; it was also unavoidably problematic as a document laying out guidelines for determining "who is or was the wife and who are the children" of the enlistees.5 Amy Dru Stanley, "Instead of Waiting for the Thirteenth Amendment: The War Power, Slave Marriage, and Inviolate Human Rights," American Historical Review 115.3 (June 2010): 733-765; "A Resolution to encourage Enlistments and to promote the Efficiency of the military Forces of the United States," Bills and Resolutions, U.S. Senate, S.R. 82, 38th Congress, 2nd Session.

The Senate's resolution "to encourage enlistments and to promote the efficiency of the military forces of the United States" prescribed two tests for determining who was the valid wife of an enlistee: evidence that the two had "lived together, or associated or cohabited as husband and wife" and continued to do so until enlistment; or, evidence provided by the couple that a marriage ceremony, whether recognized by civil authorities or not, had taken place and the couple had lived together until enlistment. For the purposes of emancipation in spring 1865, the Senate defined a valid slave marriage as requiring either cohabitation or "association" until the husband left for war. In each case, according to Sen. Charles Sumner, the evidence would not be the testimony of the master but the "mutual recognition" of the husband and wife of their marriage. The principles outlined in the bill would be carried through into the emancipation era: marriage was a volitional institution, undertaken by the consent of both husband and wife regardless of the sanction of other citizens, and that living together or associating under slavery constituted evidence of a pre-existing marriage.6 Bills and Resolutions, U.S. Senate, S.R. 82, 38th Congress, 2nd Session; U.S. Congress, Congressional Globe, Senate, 38th Congress, 2nd Session, 114; Sumner also quoted in Stanley, "Instead of Waiting," 751.

The Freedmen's Bureau undertook a program recognizing and registering these marriages by the summer of 1865, a process that proceeded differently in different states. A military order affecting North Carolina, Alabama, and Georgia declared that common law applied to slave relationships but gave little indication how that would be implemented. Other orders went into great detail laying out the calculus of who counted as a freedman's proper wife, particularly in cases where a man claimed multiple wives. In every military district commanders ordered local offices to register freedmen and women's marriages, though in Texas, these orders did not come down until 1867. The resulting records differed from place to place, both in the pieces of information officials thought essential for proper marriage registration, and in how they settled questions about who constituted a couple.7 Farmer-Kaiser, Freedwomen, 26-30; Barry A. Crouch, "The 'Chords of Love': Legalizing Black Marital and Family Rights in Postwar Texas," Journal of Negro History 79.4 (Autumn 1994): 334-351; Gutman, Black Family, 18-25, 419.

There was no straightforward hierarchy between federal law and state action in regulating marriage; the scales of bureaucracy did not nest cleanly. While federal initiative may have prompted action, in Virginia, as in a number of other southern states, the cohabitation registrations came about through state law and for reasons shaped by the concerns of whites. In February 1866, the conservative-controlled Virginia House of Delegates passed a bill requiring the registration of all people of African descent as husband and wife who were cohabiting as of the bill's passage. The bill sidestepped much of the complexity involved in formalizing slave marriages, not accounting, for example, for the possibility that many victims of the slave trade might have multiple marriages, none of which ended in divorce. In this legislation, conservative delegates were primarily concerned with two implications of emancipation: the heritability of property and the fear of that freedpeople, especially children, would become wards of the state. In every county registrars kept lists of children born from enslaved relationships along with the names of their father and mother, even if the marriage in question had dissolved. This law gave black Virginians the kind of freedom the General Assembly believed they were owed after emancipation. For Virginia whites, registering black marriages was part of a desperate attempt to restrain and confine African Americans in the wake of slavery, similar in intent and scope to the Black Codes, the series of vagrancy and apprentice laws created in the same state legislative session.8 Third Edition of the Code of Virginia: Including Legislation to January 1, 1874, George W. Munford (Richmond, 1873), Chapter 104, Section 13; J. Tivis Wicker, "Virginia's Legitimization Act of 1866," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 86.3 (Jul. 1978): 339-344; Jack P. Maddex, The Virginia Conservatives, 1867-1879: A Study in Reconstruction Politics (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1970), 39-41; Laura F. Edwards, "The Marriage Covenant is at the Foundation of All Our Rights" Law and History Review 14.1 (Spring 1996): 81-124; Catherine Jones writes of the consensus postwar Virginians held on the care of children: "The familial household's capacity to harness kinship's obligations to productive units made it prominent in Virginians' visions for the postemancipation future. This understanding of kinship informed the expectations of Virginians who looked to kin obligations to provide for dependent Virginians, notably children," in "Ties that Bind, Bonds that Break: Children in the Reorganization of Households in Postemancipation Virginia" Journal of Southern History 76.1 (February 2010): 78.

Despite state law governing these marriages, it fell to local Virginia offices of the Bureau to register them. Bureau officials were far from happy about this turn. The day after the Virginia marriage law passed, an official in Middlesex County conveyed to the Bureau's assistant commissioner for the state, Colonel Orlando Brown, his approval that freedpeople would receive state sanction for marriage; he hoped, however, that the Bureau would be left out of the registration process and that the freedmen and women would appear directly before county clerks. The local official's missive did little to shift the burden. The Bureau's regional headquarters dispatched to local field offices forms for registering freedmen and women, and certificates to be given to registrants validating their marriages. In Augusta County, Bureau officials began registering freedmen in June 1866 and projected the work to be completed by mid-July. In Frederick County, the work had begun by March 1867, but officials halted the process at least temporarily when they ran out of forms. Officials in Warren County did not begin registration until later in 1867. Counties forwarded registrations to district headquarters. By spring 1867, the civilian state government made efforts to gather registrant information from the Bureau and to have those records logged with local county clerks. Even if the state had little appetite for taking on these responsibilities, it closely guarded its prerogative to record marriages for the purposes of determining the legitimacy of children even as it shared with the Bureau the authority of binding out the children of indigent parents.9 Elizabeth Regosin, Freedom's Promise: Ex-Slave Families and Citizenship in the Age of Emancipation (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2002), 82; J. H. Remington to Orlando Brown, June 18, 1866, Valley of the Shadow online http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/papers/B1248, source available NARA, Records of the Assistant Commissioner for the State of Virginia, BRFAL, RG105, M1048, roll 18; Garrick Mallery to Orlando Brown, April 30, 1867, Valley of the Shadow online, http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/papers/B1066, source available NARA Records of the Assistant Commissioner for the State of Virginia, BRFAL, RG105, M1048, roll 26; John Thomas O'Brien, Jr., From Bondage to Citizenship: The Richmond Black Community, 1865-1867 (New York: Garland, 1990), 305-308; John Preston McConnell, Negroes and their Treatment in Virginia from 1865 to 1867 (Pulaski: B.D. Smith and Brothers, 1910), 103; Acts of General Assembly, 1866-67, 951; Mary J. Farmer, "'Because they are Women': Gender and the Virginia Freedmen's Bureau's 'War on Dependency'" in The Freedmen's Bureau and Reconstruction: Reconsiderations, ed. Paul A. Cimbala and Randall M. Miller (New York: Fordham University Press, 1999), 177.

In one sense, the bureaucratic transitions in scale worked smoothly: federal law and process intervened, states cooperated. Federal officials working at the local level implemented the legislation quickly and local governments eventually received copies of the registrations. Yet local recording of the marriages demonstrated the vexing transition to state-validated marriage. The problems with legitimizing slave marriages arose because they simply were not the same as marriages in freedom: recognition under the law created new patterns and excluded some old ones. The bureaucratic geography of marriage, descending from the federal government into local counties, intersected with freedmen and women's varying understandings of marriages. For many black Virginians, marriages had not been simple local affairs but relationships between men and women separated far from each other in space and time or living with the constant anxiety that the slave trade would tear them apart.

The cohabitation registers created by Freedmen's Bureau agents did not precisely fit the experiences and intentions of the formerly enslaved. For a variety of reasons, some marriages—in contrast to the requirements of the 1864 congressional act—were registered without the consent of both members. In Smyth County, six men registered marriages listing spouses who had died, presumably to claim their children in as strong terms as they were able. A handful of marriages included one partner as living out of state, where he or she was unlikely to appear for the registration: Dracon Braxton had married Rebecca Scott in October 1840 when they were both twenty-five, but when he appeared before Bureau officers in Hanover, Virginia, he listed her current residence as New Orleans, a testament to marriage vows made under slavery and remembered in emancipation.10Cohabitation Register, Smyth County; Dylan Penningroth, The Claims of Kinfolk: African American Property and Community in the Nineteenth-Century South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 163-186; Cohabitation Register, Hanover County, 17.

|

| Smyth County Cohabitation Register, page 2. Registering the lost: Freedmen claimed their family members in the strongest terms possible. In this registry, widowed freedmen in Smyth County recorded their marriages to Maria, Queeny, and Fannie. Adam Brown (line 1) recorded his wife, Sarah's current residence as Texas. Courtesy the Library of Virginia. |

Marriages observed in the absence of a partner could not be marriages legitimized through mutual assent. They depended on a single partner speaking on behalf of the other to make vows as permanent in law as with community sanction. Unavoidable as it was for the purpose of legitimizing children through marriage or formalizing relationships torn by the trade, a framework in which one partner spoke for the couple, immediately caused problems. Women were especially vulnerable. Mary Watkins had been living as Willis Stewart's wife near Staunton and evidently trusted her husband to register their marriage. When Stewart appeared before the local agents, however, he claimed a license to marry another woman, leaving Watkins to care for their unborn child. By walking out, some formerly enslaved women contested marriages. Living in Augusta County, Hannah Reed and David Collins registered their marriage in the summer of 1866. In September, Reed visited her mother in Winchester and by the following August had decided not to return, preferring to live there as another man's wife.11Thomas P. Jackson to Mary A. Watkins, May 27, 1867, Valley of the Shadow online, http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/papers/B0793, NARA BRFAL, RG 105, Box E4265; Cohabitation Register, Augusta County, 26; Thomas P. Jackson to John A. McDonnell, August 28, 1867, Valley of the Shadow online, http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/papers/B0123, NARA BRFAL, RG 105, Box E4269.

The framework itself could produce short-lived marriages. As Anthony Kaye has noted, enslaved men and women in the lower South not only had highly differentiated forms of intimate relationships, they developed a nuanced vocabulary for describing an ascending hierarchy of relations, from the temporary "sweethearting" and "taking up" to more permanent conditions of "living together" and marriage. The legal rubric only recognized the last of these, but it would not be surprising, given the rapidity with which some registered marriages ended, that men and women under slavery anticipated widely different futures and that the Bureau's codification of married people as "those cohabiting together as husband and wife, 1866 Feb. 27" fit awkwardly on new social conditions. Cohabiting did not accurately describe abroad marriages, and men and women in nuanced but unrecognized relationships might ascribe different meanings to what constituted a married couple. Did Hannah Reed and Willis Stewart consider prior relationships, newly codified, as marriage or permanent unions? 12Kaye, Joining Places, 52-62; the Bureau form for registering marriages in Virginia came with the printed heading, "Register of Colored Persons of ______ County, State of Virginia, cohabiting together as Husband and Wife on 27th February, 1866."

In circumstances such as these, Bureau agents expressed confusion over the bureaucratized procedure for ending marriages. Thomas Jackson, Bureau agent in Augusta, asked whether Collins and Reed's marriage might be annulled by erasing their names from the cohabitation register or whether the freedman, with limited resources, would be required to sue for divorce in order to end the marriage. The ninth sub-district headquarters in Winchester replied that the registrations carried out by federal agents had no legal effect on the marital status of the men and women involved, presumably since the marriages had been legalized by the Virginia General Assembly. "The registration," Capt. John A. McDonnell explained, was "only an evidence of marriage. He would be legally married, whether registered or not."13 Thomas P. Jackson to John A. McDonnell, August 28, 1867, Valley of the Shadow; Freedmen's Bureau Records: Thomas P. Jackson to John A. McDonnell, September 9, 1867, Valley of the Shadow. With no legal authority over the shifting relationships themselves, Bureau officials could only make lists.

The reach of federal, state, and local authority governing marriage was fluid during Reconstruction. Few legal guidelines existed before 1866, when the state instituted laws governing marriage of freedmen and women. Over the next year and a half local Bureau agents recorded marriages whose legitimacy resided with the state.

Marriage and Spatial Arrangements

Under slavery, families had taken many forms and spatial patterns. On a Georgia plantation, for example, historian Erskine Clarke found one couple who lived together as husband and wife with their children under the same roof; others had "abroad" marriages, in which the husband and wife lived on separate farms, meeting only on Saturday nights at the wife's quarters; one couple found a way to remain together even while the husband acknowledged wives and children on other plantations, although other enslaved women counted such practices as infidelity and declared their marriages finished. Marriages in Virginia showed similar diversity. The abroad marriage of Barbour and Winn took a familiar form; in Prince Edward County, enslaved men and women on Richard Randolph's large estate tended to intermarry, as many others on plantations elsewhere continued to do through the Civil War; still other enslaved men and women called each other husband and wife despite their forced separation by hundreds of miles. Each model of marriage reflected a spatial arrangement that held potential benefits in a society whose commitment to the slave trade made it fundamentally opposed to the well-being of enslaved families.14Erskine Clarke, Dwelling Place: A Plantation Epic (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007), 210-11; Melvin Patrick Ely, Israel on the Appomattox: A Southern Experiment in Black Freedom from the 1790s through the Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004), 66-67; see also Leon Litwack, Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery (New York: Random House, 1979), 239-247; and Jacqueline Jones, Labor of Love, 32-39.

|

| James F. Gibson, A Group of "Contrabands," 1862. Emancipation-era families, such as those posing here at the Foller farm in Cumberland County, Virginia, followed a variety of marriage patterns. Courtesy the Library of Congress. |

Abroad marriages proved particularly precarious. George Johnson had asked to marry a young woman on a neighboring farm in northwest Virginia. In order to block the relationship, his owner quickly sent Johnson to work on the family's plantation in Alabama. Within two years, the woman he had hoped to marry died and Johnson returned to work the farm near Harper's Ferry. William Keno lived with his mother Becky on the Dickerson farm in Frederick County, Virginia, not far from the farm on which his father Peter stayed. When John Dickerson purchased land in Florida on which to build a plantation, Keno and his mother were forced from Peter and would not see him again. Even as marriage abroad allowed large numbers of enslaved women and men to find partners, especially on the smaller farms common to Virginia and the upper South, the added flexibility ultimately left these marriages more vulnerable, more likely to be torn apart through forced removal. A marriage at the mercy of two slave owners meant twice the number of men with the opportunity of breaking the marriage.15 Benjamin Drew, A North-Side View of Slavery. The Refugee: or the Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada. Related by Themselves, with an Account of the History and Condition of the Colored Population of Upper Canada (Boston: John P. Jewett, 1856), 53, consulted in Documenting the American South online, http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/drew/drew.html; also cited in Marie Schwartz, Born in Bondage, 197; Edward E. Baptist, Creating an Old South: Middle Florida's Plantation Frontier before the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 66-67.

In spite of the constant threat of sale, slave-owners would occasionally recognize slave marriages with great fanfare. These celebrations carried no civic or legal weight, and did little to threaten the power of slave owners. Far from weakening the regime, what recognition planters gave to slave marriages was calibrated to create a smoothly functioning labor system. Campbell County planter and iron manufacturer David Ross explained early in the nineteenth century that he sought in slave marriage a labor force that avoided quarrels. "I demand moderate labour from the servants," he wrote, "and have left them free only under such control as was most congenial to their happiness. Young people might connect themselves in marriage to their own liking, with consent of their parents who were the best judges." There were very good reasons for Virginia slave-owners to give some social space to their laborers, space that might be obliterated as soon as the price was right.16 Quoted in Gutman, 159; see also Glymph, 219-220, Schwartz, 193-4, and Tadman, 133-178. Calvin Schermerhorn has argued convincingly that when faced with the conundrum of seeking "mastery" through control of labor or "money" by selling enslaved people in their prime years, Tidewater slave-owners chose to sell men and women away with little hesitation. Calvin Schermerhorn, Money over Mastery, Family over Freedom: Slavery in the Antebellum Upper South (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Despite some evidence of their observance of slave marriage, white men proved to be the single greatest threat to the institution. The Works Progress Administration interviews with Virginia ex-slaves are full of reports of slave marriages formalized by white ministers or owners. Fannie Berry, who lived in Appomattox and then Petersburg, recalled her wedding, when "Miss Sue Jones and Miss Molley Clark (white) waited on me," and when "we had everything to eat" imaginable. This recognition carried no particular safeguards against sale or violation. In nearly the same breath, Berry related to her interviewer how she fended off a local white man's attempted rape by scratching her attacker.17Weevils in the Wheat: Interviews with Virginia Ex-Slaves, ed. Charles L. Perdue, Jr. et al. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1976), 36.

|

| The Resurrection of Henry Box Brown at Philadelphia, who escaped from Richmond Va. in a box 3 feet long 2½ ft. deep and 2 ft. wide. Henry Box Brown's iconic flight North was sparked when he watched his wife and child sold South. Published by A. Donnelly, 1850. Courtesy the Library of Congress. |

The slave trade wreaked havoc on relationships. Henry Brown, an enslaved tobacco worker in Richmond, knew first hand that "no slave husband has any certainty whatever of being able to retain his wife a single hour; neither has any wife any more certainty of her husband." In 1848 Brown watched his wife and child travel with three hundred fifty others from the Richmond slave market south to the Carolinas. Brown's request that his master purchase his wife and child to keep them in Richmond left the man unswayed. "He even told me," Brown recalled, "that I could get another wife and so I need not trouble myself about that one; but I told him those that God had joined together let no man put asunder, and that I did not want another wife, but my own whom I had loved so long." Brown's separation from his wife and child led quickly to his own dramatic migration from the state; his conspirators in Richmond shipped Brown on a railcar to abolitionists in Philadelphia. Brown emerged from his hiding place to recount a story of loss that would have been familiar to thousands of other black Virginians.18Henry Box Brown, Narrative of the life of Henry Box Brown, Written by Himself (Manchester: Lee and Glynn, 1851), Documenting the American South, http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/brownbox/brownbox.html, 9, 44.

Fluctuating spatial arrangements marked enslaved marriages. At times these marriages involved a man and woman living in the same house, but as often, marriages covered great distances and were instead characterized by fragility and flexibility. Enslaved men and women in Virginia had created a system of intimate relations that could withstand many of the constraints of slavery. In light of the lack of marriageable partners residing on small farms, and without the possibility of moving voluntarily, freedmen and women entered into many different kinds of intimate living arrangements. Most common was living abroad, an arrangement that left marriages vulnerable to forced separation of much wider distances, separations that often meant the end of the marriage.

Marriage and Migration

The migrations freedmen and women experienced over the course of their lives—in many cases spanning a thousand miles or more—shaped their marriages in large and small ways. Emigration from Virginia made up about 45 percent of all interstate migrations of enslaved men and women in the antebellum period. In the 1830s alone, nearly three in ten enslaved people living in the state were forcibly removed from the Tidewater region. In the decade immediately preceding the Civil War, a quarter of the enslaved men, women, and children living in Virginia's Valley were sent away. All told, more than half a million enslaved men and women were taken from the state between 1790 and 1860, about half of these likely removed through the slave trade.19Philip Troutman, "Slave Trade and Sentiment in Antebellum Virginia," PhD Dissertation, University of Virginia, 419; Jonathan B. Pritchett, "Quantitative Estimates of the United States Interregional Slave Trade, 1820-1860," Journal of Economic History 61.2 (Jun. 2001): 468; Tadman, Speculators and Slaves, 12.

|

| Scott Nesbit, Migration and Marriage in Postemancipation Virginia, 2010. Use this interactive map to explore migration and marriage data used in this essay. |

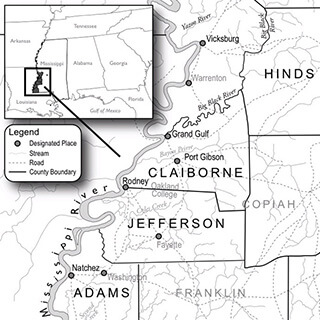

Intrastate migration was equally robust. Researchers at the Library of Virginia have shared with the public scanned and transcribed versions of the cohabitation records—which the General Assembly instructed be kept at local county courthouses—from all parts of the state. These registers record the names of ten thousand husbands and wives, how long they had been married, their place of residence in 1866, their birthplaces, husband's occupation, and often the names of their children and former owners. Nathan Altice, a programmer at the University of Richmond's Digital Scholarship Lab, has developed an interactive map that allows exploration of the distinct patterns of migration and marriage that emerge from these records. These patterns hold significance for nearly every aspect of emancipation-era life, giving shape to freedmen and women's experience of and possibilities for marriage, child-rearing, work, and politics.

Husbands and wives experienced slavery in such different ways that it is not surprising that their migration patterns differ. In nearly every marriage register, more men than women underwent migrations to a new county. The differences were often dramatic.For example, nearly two out of three migrants to Warren County, in the northern Shenandoah Valley, were men. A number of factors intersected to bring about lower mobility rates among women whose marriages were registered, including the more fluid labor markets for male than female labor. Perhaps the responsibility of caring for children made women slightly less likely to move in their lifetime, either voluntarily or by force.20An equal number of men and women were migrants in Lunenburg Co., the only outlier. Michael Tadman's analysis of the interregional slave trade in the 1850s uses different evidence but similarly indicates that for all age cohorts except slaves between the ages of ten and twenty, more men than women had been sold away from their homes. Tadman, Speculators and Slaves, 29-31. On the different experiences of men and women under slavery, see Glymph, House of Bondage; Jacqueline Jones, Labor of Love; Brenda Stevenson, Life in Black and White.

Whether husbands and wives experienced migration to a different county depended largely on whether they lived east or west of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Those still living in long settled counties in eastern Virginia, which had seen a steady flow of men and women forced to other places, were relatively unlikely to have been born elsewhere. In every Piedmont and Tidewater county more than half of all married people were living in the county of their birth in 1866. Those who had not migrated made up nearly three quarters of those married in the overwhelmingly rural and tobacco-growing Lunenburg County. Maria and William Bagley were similar to most couples still living in Lunenburg: both were born and continued to live there. Since the Bagleys did not share an owner, they likely lived abroad, though this did not keep them from raising eight children in their eighteen years of marriage.21Register, Lunenberg Co.

|

| Scott Nesbit, Percent of Married Men and Women who had Migrated from their Birth Counties, 2010. The Blue Ridge Mountains separated the Valley and Appalachia sections of Virginia from the Piedmont and Tidewater. They also divided counties in which most men and women had experienced migration from those in which most had not. Interactive Map |

The Great Valley and Appalachian counties suffered tremendous outmigration, but had experienced significant in-migration as well. Of counties west of the Blue Ridge, only in Augusta (52 percent) and Wythe (53 percent) were most freedmenfre and women born where they were married. Only about one in four of those who registered to be married in Floyd County, for example, were born there. More couples in western counties shared migration trajectories similar to those of Madison Hampton, who had moved to Floyd from Rye Valley Virginia in nearby Wythe County, and his wife Edie, who was originally from Suffolk. Like the Hamptons, the many men and women who had been born elsewhere most often had come from other counties in Virginia. In none of the twelve counties included in our database did those born outside the state comprise more than a handful of those registering to be married.22 Dunaway, African-American Family, 18-36; Register, Augusta Co.; Register, Wythe Co.; Register, Floyd Co.

Most black Virginians, particularly those marrying in the eastern counties, chose a wife or husband from the county where they were born. In Caroline County, a tobacco-growing county north of the state capitol in Richmond, nearly three quarters of married men and women shared a birthplace with their partner. In most instances, this meant that both husband and wife were born in Caroline and continued to live there after the end of slavery. Far more couples in the southwest Virginia counties of Roanoke, Smyth, Wythe, and Floyd were like Clara Anderson and Robert Preston. They were born in Tazewell and Bedford Counties, respectively, and were living together in Wytheville when they registered their relationship in 1866. In Appalachia, even those who married spouses from their home counties, such as Martha and Cornelius Harrison, both from Campbell County, migrated together elsewhere disproportionately as the Harrisons did when they ended up in Smyth County.23 Register, Caroline Co. Only 28 percent of couples married in Caroline Co. were born in different counties from each other. Six percent moved together from another county. Two thirds of marriages were comprised of men and women born in Caroline. In Floyd County, 59 percent of couples did not share a birth county. Only nine percent of couples who registered there shared Floyd as their birthplace. Nearly one third of registering couples were migrants to Floyd from the same county; for more, see "Joint Migration" in the accompanying application, "Migration and Marriage in Postemancipation Virginia".

Men and women formed long-term relationships in eastern and western corners of the state alike. In spite of the obstacles to stable relationships, long marriages were not uncommon among black Virginians who registered their marriages in the immediate postwar era—the median length of relationship legitimized in the cohabitation registers was ten years. As one might suspect, a number of the long-term marriages occurred among slaves claimed by the same owner. G. W. and Lucinda Allman had been husband and wife for more than forty years and listed seven adult children; both were born in Lunenburg County, continued to live there in 1866, and listed William Allman as their last owner. Others, however, seem to have traveled a considerable distance to reunite. Brock Wells married Martha Sheler when he was nineteen years old, in 1837, and they probably lived near each other for a number of years, until at least 1846 when their youngest daughter Rosa was born. When asked the residence of their last owner, however, Martha indicated that she had lived at the Epperly farm in Floyd County. Wells had been moved far from southwest Virginia, at the plantation of an "R. Wells," in Missouri. Wells was able to return to his home after the war, however, to rejoin Sheler in Floyd County and live there long afterward.24Cohabitation Register, Lunenburg County, 1; Cohabitation Register, Floyd County, 1; 1880 United States Federal Census [database on-line], Little River, Floyd, Virginia, Roll 1365, Page 354C, Enumeration District 29, http://ancestry.com.

The likelihood that former slaves would report long-term marriages varied neither by the setting in which they took place nor by the migration profile of the county in which they were recorded. Herbert Gutman found that in North Carolina, the percentage of freedpeople reporting long marriages in 1866 was the same in farm and urban settings as in plantation settings. The median length of marriages among freedmen and women in Virginia varied from county to county, but not in a way that maps neatly to the patterns of migration. Floyd County, where men and women were most likely to have experienced migration, had the shortest median marriage, seven and a half years. But Warren County, which also had a relatively high level of migration, was among the counties with the longest median length of marriage, twelve years.25Gutman, Black Family, 102; Cohabitation Registers, Floyd County, Warren County.

Men and women who moved, voluntarily or by force, to counties in the Tidewater often moved only a short distance, from other Tidewater counties or from the Piedmont. Very few men and women born in the western parts of the state ended up in the east. James Brooks, a thirty-five-year-old house servant born in Frederick County in the far northwest corner of the state, who married Lucy Oldon, from the closer county of King George, was the exception that proved the rule. Brooks was one of eight registrants in Hanover County, born outside the Piedmont and Tidewater areas out of more than one thousand; of these eight migrants across regional boundaries, four were from western Virginia, and the others were born in other states.26 Cohabitation Register, Hanover County, 1.

|

| Scott Nesbit, Migration to Richmond County, 2010. Tidewater counties saw few migrants, forced or not, from the western part of the state. None of the men and women who registered their marriage in Richmond County were born west of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Interactive Map |

Those married in western counties not only were more likely to have migrated, but often moved greater distances and across more varied terrain as well. In Smyth County, in the southwest of the state, fewer than one hundred couples registered their marriages yet men and women from all parts of the state made their homes there. Migrants from eighteen eastern counties had moved to Smyth, along with natives of five other states.27 176 men and women registered their marriages in Smyth County. This represented about one seventh of the black population in Smyth if the black population in 1866 matches that recorded in the 1870 census. The cohabitation registers for most counties listed between 10 percent and 23 percent of the black population of the county; Warren County was an outlier, with records for about 42 percent of the black population recorded in 1870. Some of this discrepancy for Warren can be ascribed to an unusually large number of registrants who listed their current residence as a county other than Warren. Cohabitation Register, Smyth County.

In all counties the majority of migrants came from nearby, though the networks in which black men and women were involved tied counties unevenly. Far more men and women married in Augusta were from Albemarle than any other neighboring county. This was in part true because Albemarle had a much higher black population than did any other neighboring county. The train running west from Charlottesville to Staunton surely played a role as well, as did the relative ease with which men could find work in Augusta and much of the Valley. Far more men and women born in Pulaski County ended up living in Wythe, the adjoining county to the west, than any other county for which we have records. No one from Pulaski registered a marriage in Floyd County, to the immediate southeast. Few men and women from Henrico, the most populous county in the area, seem to have moved to the adjacent county of Hanover. Distance between places could be measured in units other than miles. Henrico and Hanover, sharing a border of over thirty miles, were far more distant from each other than Augusta and Albemarle, whose boundary extended less than half that length. The ties that bound communities together did not depend on abstract measurements but on labor flows and consequent journeys of men and women across political borders.28 Cohabitation Register, Augusta County; on labor supply in the Valley, see John A. McDonnell to Orlando Brown, February 3, 1868, NARA, Records of the Assistant Commissioner for the State of Virginia, BRFAL, RG105, M1048, roll 58, Valley of the Shadow, http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/papers/B1206; Cohabitation Registers, Wythe County and Hanover County.

Virginia's emancipation-era marriages formed a relational geography tying diverse places together in patterns that would be invisible on a political or topographical map. Men and women from Halifax County Virginia, in the heart of the Southside tobacco belt, had more ties to Roanoke County, several days' walk to the west, than they did to the seemingly much closer, Piedmont county of Lunenburg. Men and women experienced their marriages and the journeys they took in two ways. In one way, these scales of action are measurable, covering defined spaces and quantifiable distances in feet above sea level or the number of miles between points on a map. But they were also constructed through experience, stretching and bending mapped spaces, connecting places, shrinking the distance between some locales and neighborhoods while making others seem much greater than a comparison of latitudes and longitudes would indicate.

The ties between counties seemed to depend on the migrants' occupations. Caroline and Louisa Counties were each adjacent to Hanover County; some fifty men from each county migrated to Hanover. These migrations, from equally rural districts, were heavily patterned by occupation. A large majority (85 percent) of married freedmen in Hanover County were agricultural labors. Twenty-five percent of migrants from Caroline County to Hanover County listed non-agricultural occupations; only three migrants from Louisa were non-agricultural laborers. The discrepancy does not arise from an abundance of artisans trained in Caroline; only four percent of registrants married in Caroline County listed non-agricultural occupations. Skilled workers and those who sought non-agricultural work were overwhelmingly drawn, whether voluntarily or by force, from Caroline County to the neighboring county of Hanover.29Cohabitation registers, Caroline County, Hanover County.

The creation of households, in other words, occurred across space, was marked by patterns of forced and voluntary migration, and laid the groundwork for potentially useful networks of kinship. Artisans in places like Caroline, seemed to leave the county disproportionately for its neighboring county to the south; one can imagine that farmers participating in volatile produce markets could benefit from knowledge of commercial networks—even knowledge based on painful experience—in other, far-flung communities. In a number of circumstances, we might imagine such connections doing little good. Fewer than a third of African Americans elected to Virginia state office in Reconstruction, for example, were migrants from another county. Political leadership for Virginia blacks in Reconstruction seemed to depend not on statewide kinship networks or national connections but on deep roots and dense networks within a single locale.30Luther P. Jackson, Negro Office Holders in Virginia, 1865-1895 (Norfolk: Guide Quality Press, 1945). The number includes those born in other states. Twenty-eight office holders were born in places other than the counties they represented. Of these, twelve were born in adjacent counties. Fifty-seven delegates were born in the county they represented. We lack birthplace information for fifteen delegates.

Emancipation transformed the spaces enslaved men and women created through their marriages. A legal framework that guaranteed the end of forced, long-distance removal and the slave trade bolstered black marriages of all sorts. As black women increasingly found ways to avoid close contact with white men, living arrangements began to shift. Legal marriages defensible in court made white attempts to break up black families far less likely to succeed. Yet for all the benefits of emancipation felt immediately by families, repair took time.

The diversity of living arrangements that marked fragile, intimate relationships under slavery continued in freedom. William and Isabella Gibbons, who had married in the 1850s, each followed promising livelihoods soon after emancipation. She remained in Charlottesville teaching in the local freedmen's school and for a few years he secured a position as minister at the African Baptist Church there. By 1867, however, he had taken a position a half day's travel away via the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, in Washington, DC, serving as the minister of a thriving church while returning, when his duties permitted, to his wife and children. Mary Blackburn had lived apart from her free husband, John Patrick, before he bought her in 1860 and they began living together in Middlebrook, a small farming town in the Shenandoah Valley. This relative distance from their neighbor and her former master, Henry Mish, did not protect their three young children from sale, nor did it enable them to find the children in the years immediately after the war.31"Reminiscences of Philena Carkin," 50-53, unpublished manuscript, Philena Carkin Papers, 1866-1875, Accession #11123, Special Collections Dept., University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.; Gayle Schulman, "The Gibbons Family: Freedmen" Magazine of Albemarle County History 55 (1997): 60-93; Southern Claims Commission: Claim of Mary Blackburn, 1875, Claim no. 1378, Valley of the Shadow online, http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/claims/SCC0518, also available as National Archives, College Park, RG 217, claim #1378.

Black men and women spent considerable time and energy repairing what the slave trade had broken, at times using the newly invigorated federal bureaucracy to accomplish this task. Reuben Skelter registered his marriage to Sally Fitzhugh based on his residence in Caroline County, Virginia, listing her current place of residence as Georgia. Adam Brown testified in the Smyth County register to his twenty-five year marriage to his wife Sarah and made sure agents recorded the names of their five children, but believed that his wife lived in Texas. Ann, who had lived at the Crabtree farm with her four children, documented her marriage to Alfred Crabtree but had no idea where he was living. At the end of the war Violet Ward sought assistance from the network created by Freedmen's Bureau agents to reunite her scattered family. She lived with one of her children in Staunton, Virginia; another child lived in Richmond; her husband and their second child were living in Holmes County, Mississippi. Lost kin notices flooded the Christian Recorder and other black periodicals, documenting the process of family reunion in midstream while giving little indication whether the reunions eventually were accomplished.32Amy Murrell Taylor, The Divided Family in Civil War America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 196-198; Cohabitation Register, Caroline County, 19; Cohabitation Register, Smyth County; W. Storer How to Orlando Brown, September 16, 1865, Valley of the Shadow online; Michael P. Johnson, "Looking for Lost Kin: Efforts to Reunite Freed Families after Emancipation," in Catherine Clinton, ed., Southern Families at War: Loyalty and Conflict in the Civil War South (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 15-34.

Forced migration made some potential reunions painful. Laura Spicer had been sold away from her home to Gordonsville and never remarried. With emancipation, the opportunity came when she and her husband might reunite. Her husband, however, was torn between his former marriage to Spicer and his current family. "The reason why I have not written you before, in a long time," he wrote, "is because your letters disturbed me so very much….I want to see you and I don't want to see you. I love you just as well as I did the last day I saw you," though, he admitted, there were troubling reasons he could not see his wife Laura and their children. "I am married, and my wife have two children, and if you and I meet it would make a very dissatisfied family. " For Spicer and her former husband, there was no straightforward way to translate the marriage that had existed into the emancipation era.33 Henry L. Swint, ed. Dear Ones at Home: Letters from Contraband Camps (Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 1966), 241-2.

Conclusion

Bureau agents and black ministers attempted to bring structure to relationships such as these, fitting them neatly into categories of marriage that might form the basis for property relations and for determining dependency of the infirm and young alike. Peter Randolph, who had spent his childhood enslaved in Prince George County, recalled the difficulty of his role as pastor in circumstances in which "hundreds of those who had been separated" returned home and "found their former companions married again" because they had expected never to see their spouses again. The "perplexing part" for Randolph was "to determine which were the right ones to marry," particularly when at the time of the marriage formalization law he was marrying "seven and eight couples a night." The forced migrations men and women experienced over the course of their lives created the emotional strains, difficult religious judgments, and chaotic bureaucratic processes that accompanied marriage formalization.34 Peter Randolph, From Slave Cabin to the Pulpit, the Autobiography of Rev. Peter Randolph: The Southern Question Illustrated and Sketches of Slave Life (Boston: James H. Earle, 1893), 89-90.

Accounting for the migrations men and women had been forced to endure was, as Randolph wrote, the most perplexing part of postemancipation marriage. It was a problem of scale. Marriage seemed, to those formalizing relationships of freedmen and women, to imply fixed temporal and spatial bounds; it had a beginning and end date, required cohabitation, and was by definition monogamous. Marriage required such boundaries if it were to serve as the basis for judgments about property and dependence and if it were to serve as an institution that could anchor the private sphere. The scale at which many freedmen and women had experienced marriage defied all those hallmarks.

Emancipation-era marriages endured multiple transitions in a few short years. Some of these transitions involved movement through space, reuniting couples and families that had been pulled apart in slavery and through the Civil War. Other transitions were legal and contextual, as the meaning of marriage for black men and women shifted dramatically under their feet. In the words of Ira Berlin, Steven F. Miller, and Leslie Rowland, "the personnel was familiar, but the circumstances entirely different." For freedmen and women, managing both transitions involved sophisticated navigation across multiple scales of action. They leveraged bureaucracies, kinship networks, and social hierarchies at the local level and across hundreds of miles to reestablish the most intimate bonds.35Ira Berlin, Steven F. Miller, and Leslie Rowland, "Afro-American Families and the Transition from Slavery to Freedom" Radical History Review (1988): 89-121.

Thinking about marriage at multiple scales allows us to draw new connections between some of the most important writing on emancipation and the family. Thavolia Glymph's powerful account of one particular scale, the plantation household, has shown how the divisions between public and private space in the plantation South were at their heart ideological, violent, and obfuscatory. Anthony Kaye has revealed that enslaved communities in the Mississippi Valley organized themselves at the level of the neighborhood as a coherent, if porous, unit. Laura Edwards has shown how political debate at the state level depended crucially on legal ideas about household economy. Black men and women worked across each of these scales and others to bring about the seemingly most self-contained relationships. The assignation of "public" to state-level action and "private" to household institutions was a fiction. Even the designation of marriage as an institution that existed at a single scale, the household, was a distortion of how intimate ties existed in relation to wider networks.

The notion that the household was a private space coextensive with marriage, the quintessential private institution, was a spatial fiction foundational for the dichotomies of public and private life about which Glymph, Edwards, and others have written so eloquently. Marriage did not function solely within the bounds of the private residence or yard, nor did it exist at a single scale. Black women and men were constantly acting at multiple scales, using governmental agents, employers, and even former slaveholders to buttress their claims to their families. Freedmen and women shaped the physical, social, and cultural space necessary to make their marriages work. Their relationships emerged from an antebellum system that at times constrained their movement to a single farm and at others forced migration far away from kin. Their marriages were bolstered by the seemingly incongruous bureaucratic cooperation between radicals in Congress and conservatives in the Virginia state legislature. And they were built by men and women who had, in all likelihood, either been forced to move or who had been separated from loved ones on account of the intricate, devastating patterns of the slave trade. The men and women entering into these marriages created new geographies suited for freedom. In those geographies, living abroad could create opportunities, husbands and wives found intimate spaces away from those who most threatened them, and families had a chance to retrace the long lines of the slave trade to find loved ones.

About the Author

Scott Nesbit is the Associate Director of the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of Richmond, where he works on projects involving geographic information systems and the humanities. He is completing a dissertation on spatial changes attending emancipation at the University of Virginia.

About the Interactive Mapmaker

Nathan Altice is the Tocqueville web developer at the University of Richmond's Digital Scholarship Lab. He is currently pursuing his PhD in Media, Art + Text at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Recommended Resources

Print Materials

Bardaglio, Peter. Reconstructing the Household: Families, Sex, and Law in the Nineteenth-Century South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Berlin, Ira, Steven F. Miller, and Leslie Rowland. "Afro-American Families and the Transition from Slavery to Freedom," Radical History Review 42 (1988).

Cimbala, Paul A, and Randall M. Miller. The Freedmen's Bureau and Reconstruction: Reconsiderations. New York: Fordham University Press, 1999.

Dunaway, Wilma A. The African American Family in Slavery and Emancipation. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Glymph, Thavolia. Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Kaye, Anthony. Joining Places: Slave Neighborhoods in the Old South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Regosin, Elizabeth. Freedom's Promise: Ex-Slave Families and Citizenship in the Age of Emancipation. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2002.

Stanley, Amy Dru. From Bondage to Contract: Wage Labor, Marriage, and the Marketplace in the Age of Slave Emancipation. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Links

Lazzerini, Rickie. "African Americans on the Move: A Look at the Forced and Voluntary Movement of Blacks Within America," Kindred Trails, 2006.

http://www.kindredtrails.com/African-Americans-On-The-Move-1.html.

Shaffer, Donald R. and Elizabeth Regosin. "Voices of Emancipation: Union Pension Files Giving Voice to Former Slaves," Prologue 4 (2005).

http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2005/winter/voices.html.

The Valley of the Shadow, Virginia Center for Digital History.

http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/VoS/usingvalley/valleyguide.html.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Register of Colored Persons of Augusta County, State of Virginia, Cohabiting Together as Husband and Wife, 1866 Feb. 27 (hereafter Cohabitation Register, Augusta County), 28. Cohabitation Registers Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA, http://digitool1.lva.lib.va.us:8881/R?func=collections-result&collection_id=1522; U.S. Bureau of the Census, Eighth Census of the United States, 1860. Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, 1860, M653, 1,438 rolls, source consulted: s.v. P. Cleveland, 1860 United States Federal Census, Slave Schedules, Albemarle County, Virginia, http://www.ancestry.com/; P. Cleveland to [Thomas P. Jackson], May 6, 1867, Valley of the Shadow: Two Communities in the American Civil War online, http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/papers/B0193, source copy available as National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (hereafter hereafter NARA BRFAL), Record Group 105, Box E4269; 1870 U.S. Federal Census, http://ancestry.com/ s.v. Benjamin Barbourn [Barbour], District 3, Augusta, Virginia, M593_1634, page 370B. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Valley Virginian, February 21, 1866, p. 3 col. 2, Valley of the Shadow online, http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/news/vv1866/va.au.vv.1866.02.21.xml#03; U.D. Poe to P.P. Cleveland, April 30, 1867, Valley of the Shadow online, http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/papers/B0192 source available NARA BRFAL, RG 105; P. Cleveland to [Thomas P. Jackson], May 6, 1867, Valley of the Shadow online; 1860 U.S. Federal Census, Agriculture Schedule, http://www.ancestry.com/ s.v. Robt Van Lear, Augusta County, Virginia, roll 5, p. 273; Augusta County: Freedmen's Bureau Register of Complaints, May 8, 1866, Valley of the Shadow online, http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/papers/BD4000, source available, NARA BRFAL, RG 105, Box E4237. |

| 3. | Geographers have disagreed about many aspects of the definition of scale. See Peter Taylor, "A Materialist Framework for Political Geography," Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, n.s., 7, no. 1 (1982): 15-34; Neil Smith, Uneven Development: Nature, Capital, and the Production of Space (Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell, 1984); Sallie A. Marston, "The Social Construction of Scale" Progress in Human Geography 24, no. 2 (2000): 219-242; Andrew E. G. Jonas, "Pro Scale: Further Reflections on the 'Scale Debate' in Human Geography," Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, n.s., 31, no. 3 (2006): 399-406; and Edward L. Ayers and Scott Nesbit, "Seeing Emancipation: Scale and Freedom in the American South," Journal of the Civil War Era 1, no. 1 (2011): 3-22. |

| 4. | For scholarship on African American families at these and other scales, see Thavolia Glymph, Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008); Anthony Kaye, Joining Places: Slave Neighborhoods in the Old South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007); Brenda Stevenson, Life in Black and White: Family and Community in the Slave South (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997); Laura Edwards, Gendered Strife and Confusion: The Political Culture of Reconstruction (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1997); Wilma A. Dunaway, The African American Family in Slavery and Emancipation (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003); Jacqueline Jones, Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family from Slavery to the Present (New York: Basic Books, 1985); Amy Dru Stanley, From Bondage to Contract: Wage Labor, Marriage, and the Marketplace in the Age of Slave Emancipation (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998); Peter Bardaglio, Reconstructing the Household: Families, Sex, and Law in the Nineteenth-Century South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995); Mary Farmer-Kaiser, Freedwomen and the Freedmen's Bureau: Race, Gender, and Public Policy in the Age of Emancipation (New York: Fordham University Press, 2010); recent investigations of families' transition to emancipation build on an earlier historiographical debate: E. Franklin Frazier, The Negro Family in the United States (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1939); Daniel P. Moynihan, The Negro Family: The Case for National Action (Washington, DC: Office of Policy Planning and Research, U.S. Department of Labor, 1965); John W. Blassingame, The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972); and Herbert G. Gutman, The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750-1925 (New York: Pantheon, 1976). |

| 5. | Amy Dru Stanley, "Instead of Waiting for the Thirteenth Amendment: The War Power, Slave Marriage, and Inviolate Human Rights," American Historical Review 115.3 (June 2010): 733-765; "A Resolution to encourage Enlistments and to promote the Efficiency of the military Forces of the United States," Bills and Resolutions, U.S. Senate, S.R. 82, 38th Congress, 2nd Session. |

| 6. | Bills and Resolutions, U.S. Senate, S.R. 82, 38th Congress, 2nd Session; U.S. Congress, Congressional Globe, Senate, 38th Congress, 2nd Session, 114; Sumner also quoted in Stanley, "Instead of Waiting," 751. |

| 7. | Farmer-Kaiser, Freedwomen, 26-30; Barry A. Crouch, "The 'Chords of Love': Legalizing Black Marital and Family Rights in Postwar Texas," Journal of Negro History 79.4 (Autumn 1994): 334-351; Gutman, Black Family, 18-25, 419. |

| 8. | Third Edition of the Code of Virginia: Including Legislation to January 1, 1874, George W. Munford (Richmond, 1873), Chapter 104, Section 13; J. Tivis Wicker, "Virginia's Legitimization Act of 1866," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 86.3 (Jul. 1978): 339-344; Jack P. Maddex, The Virginia Conservatives, 1867-1879: A Study in Reconstruction Politics (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1970), 39-41; Laura F. Edwards, "The Marriage Covenant is at the Foundation of All Our Rights" Law and History Review 14.1 (Spring 1996): 81-124; Catherine Jones writes of the consensus postwar Virginians held on the care of children: "The familial household's capacity to harness kinship's obligations to productive units made it prominent in Virginians' visions for the postemancipation future. This understanding of kinship informed the expectations of Virginians who looked to kin obligations to provide for dependent Virginians, notably children," in "Ties that Bind, Bonds that Break: Children in the Reorganization of Households in Postemancipation Virginia" Journal of Southern History 76.1 (February 2010): 78. |

| 9. | Elizabeth Regosin, Freedom's Promise: Ex-Slave Families and Citizenship in the Age of Emancipation (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2002), 82; J. H. Remington to Orlando Brown, June 18, 1866, Valley of the Shadow online http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/papers/B1248, source available NARA, Records of the Assistant Commissioner for the State of Virginia, BRFAL, RG105, M1048, roll 18; Garrick Mallery to Orlando Brown, April 30, 1867, Valley of the Shadow online, http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/papers/B1066, source available NARA Records of the Assistant Commissioner for the State of Virginia, BRFAL, RG105, M1048, roll 26; John Thomas O'Brien, Jr., From Bondage to Citizenship: The Richmond Black Community, 1865-1867 (New York: Garland, 1990), 305-308; John Preston McConnell, Negroes and their Treatment in Virginia from 1865 to 1867 (Pulaski: B.D. Smith and Brothers, 1910), 103; Acts of General Assembly, 1866-67, 951; Mary J. Farmer, "'Because they are Women': Gender and the Virginia Freedmen's Bureau's 'War on Dependency'" in The Freedmen's Bureau and Reconstruction: Reconsiderations, ed. Paul A. Cimbala and Randall M. Miller (New York: Fordham University Press, 1999), 177. |

| 10. | Cohabitation Register, Smyth County; Dylan Penningroth, The Claims of Kinfolk: African American Property and Community in the Nineteenth-Century South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 163-186; Cohabitation Register, Hanover County, 17. |

| 11. | Thomas P. Jackson to Mary A. Watkins, May 27, 1867, Valley of the Shadow online, http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/papers/B0793, NARA BRFAL, RG 105, Box E4265; Cohabitation Register, Augusta County, 26; Thomas P. Jackson to John A. McDonnell, August 28, 1867, Valley of the Shadow online, http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/papers/B0123, NARA BRFAL, RG 105, Box E4269. |

| 12. | Kaye, Joining Places, 52-62; the Bureau form for registering marriages in Virginia came with the printed heading, "Register of Colored Persons of ______ County, State of Virginia, cohabiting together as Husband and Wife on 27th February, 1866." |

| 13. | Thomas P. Jackson to John A. McDonnell, August 28, 1867, Valley of the Shadow; Freedmen's Bureau Records: Thomas P. Jackson to John A. McDonnell, September 9, 1867, Valley of the Shadow. |

| 14. | Erskine Clarke, Dwelling Place: A Plantation Epic (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007), 210-11; Melvin Patrick Ely, Israel on the Appomattox: A Southern Experiment in Black Freedom from the 1790s through the Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004), 66-67; see also Leon Litwack, Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery (New York: Random House, 1979), 239-247; and Jacqueline Jones, Labor of Love, 32-39. |

| 15. | Benjamin Drew, A North-Side View of Slavery. The Refugee: or the Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada. Related by Themselves, with an Account of the History and Condition of the Colored Population of Upper Canada (Boston: John P. Jewett, 1856), 53, consulted in Documenting the American South online, http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/drew/drew.html; also cited in Marie Schwartz, Born in Bondage, 197; Edward E. Baptist, Creating an Old South: Middle Florida's Plantation Frontier before the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 66-67. |

| 16. | Quoted in Gutman, 159; see also Glymph, 219-220, Schwartz, 193-4, and Tadman, 133-178. Calvin Schermerhorn has argued convincingly that when faced with the conundrum of seeking "mastery" through control of labor or "money" by selling enslaved people in their prime years, Tidewater slave-owners chose to sell men and women away with little hesitation. Calvin Schermerhorn, Money over Mastery, Family over Freedom: Slavery in the Antebellum Upper South (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011). |

| 17. | Weevils in the Wheat: Interviews with Virginia Ex-Slaves, ed. Charles L. Perdue, Jr. et al. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1976), 36. |

| 18. | Henry Box Brown, Narrative of the life of Henry Box Brown, Written by Himself (Manchester: Lee and Glynn, 1851), Documenting the American South, http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/brownbox/brownbox.html, 9, 44. |

| 19. | Philip Troutman, "Slave Trade and Sentiment in Antebellum Virginia," PhD Dissertation, University of Virginia, 419; Jonathan B. Pritchett, "Quantitative Estimates of the United States Interregional Slave Trade, 1820-1860," Journal of Economic History 61.2 (Jun. 2001): 468; Tadman, Speculators and Slaves, 12. |

| 20. | An equal number of men and women were migrants in Lunenburg Co., the only outlier. Michael Tadman's analysis of the interregional slave trade in the 1850s uses different evidence but similarly indicates that for all age cohorts except slaves between the ages of ten and twenty, more men than women had been sold away from their homes. Tadman, Speculators and Slaves, 29-31. On the different experiences of men and women under slavery, see Glymph, House of Bondage; Jacqueline Jones, Labor of Love; Brenda Stevenson, Life in Black and White. |

| 21. | Register, Lunenberg Co. |

| 22. | Dunaway, African-American Family, 18-36; Register, Augusta Co.; Register, Wythe Co.; Register, Floyd Co. |

| 23. | Register, Caroline Co. Only 28 percent of couples married in Caroline Co. were born in different counties from each other. Six percent moved together from another county. Two thirds of marriages were comprised of men and women born in Caroline. In Floyd County, 59 percent of couples did not share a birth county. Only nine percent of couples who registered there shared Floyd as their birthplace. Nearly one third of registering couples were migrants to Floyd from the same county; for more, see "Joint Migration" in the accompanying application, "Migration and Marriage in Postemancipation Virginia". |

| 24. | Cohabitation Register, Lunenburg County, 1; Cohabitation Register, Floyd County, 1; 1880 United States Federal Census [database on-line], Little River, Floyd, Virginia, Roll 1365, Page 354C, Enumeration District 29, http://ancestry.com. |

| 25. | Gutman, Black Family, 102; Cohabitation Registers, Floyd County, Warren County. |

| 26. | Cohabitation Register, Hanover County, 1. |

| 27. | 176 men and women registered their marriages in Smyth County. This represented about one seventh of the black population in Smyth if the black population in 1866 matches that recorded in the 1870 census. The cohabitation registers for most counties listed between 10 percent and 23 percent of the black population of the county; Warren County was an outlier, with records for about 42 percent of the black population recorded in 1870. Some of this discrepancy for Warren can be ascribed to an unusually large number of registrants who listed their current residence as a county other than Warren. Cohabitation Register, Smyth County. |