Overview

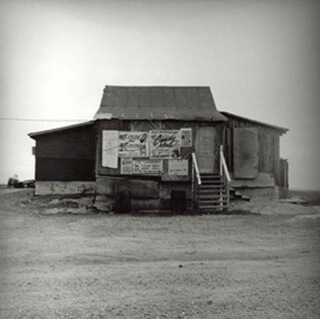

In this multimedia presentation, Steve Bransford assembles field recordings and photographs of George Mitchell. Bransford combines original documentary footage of area musicians with contextualizing scholarly materials to offer an introduction to the rich and varied blues styles of the Lower Chattahoochee Valley.

Introduction

The Lower Chattahoochee River Valley region has a rich tradition of blues music, but if it weren't for the efforts of field researcher George Mitchell from 1969 until the early 1980s, this blues history would be largely unknown. The Lower Chattahoochee is most well-known as home to Gertrude "Ma" Rainey (1882–1939), one of the most celebrated early "classic blues" singers. The mostly band-oriented style that Rainey popularized, however, differs from the country blues that Mitchell found. Instead, Mitchell's fieldwork led him to find a rural, down-home country blues that typically features one or two musicians and an acoustic guitar. Unfortunately, there were no commercial recordings of country blues made by Lower Chattahoochee Valley musicians in the 78 RPM record era, largely because no major roads connected the Lower Chattahoochee to Atlanta, the closest recording hub. And in the early 1960s, when blues aficionados and folk revivalists scoured the South for remaining practitioners of country blues, they did not search the Lower Chattahoochee.

In 1967, George Mitchell conducted field research in Mississippi, locating such blues musicians as Joe Callicott, who had recorded in the prewar era, as well as the previously unrecorded R.L. Burnside. In 1969, Mitchell moved to Columbus, Georgia, to work for the Columbus Ledger newspaper. After his experience recording and photographing in Mississippi, he tried to locate blues musicians in the countryside around Columbus. On weekends, he and his wife Cathy drove within a fifty-mile radius, and, to their great delight, learned that the area was filled with exceptional blues players. "Every small town had at least one blues singer," Mitchell recalls in an interview. "It was astounding, to go down the counties on either side of the Chattahoochee River in Alabama and Georgia and find this rich of a musical tradition."

Blues scholar David Evans breaks down early blues performance styles into three regionally differentiated approaches: one that includes East Texas and adjacent portions of Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana; a second stylistic region in the Deep South extending from the Mississippi Valley eastward to Central Georgia; and a third style—often referred to as Piedmont blues—that "encompasses the East Coast from Florida to Maryland, stretching westward through the Piedmont, the Appalachian Mountains, and the Ohio River Valley to central Kentucky and Tennessee." Geographically, the Lower Chattahoochee Valley fits within the Deep South, but musically its blues is much closer to the fingerpicking Piedmont style, which often features "alternating bass notes or an alternating bass note and chord, in the manner of ragtime, with spectacular virtuoso playing in the treble range."1Evans, David. "The Development of the Blues." Chapter. In The Cambridge Companion to Blues and Gospel Music, edited by Allan Moore, 20–43. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. Mitchell recorded several Lower Chattahoochee blues artists covering songs by Blind Boy Fuller, one of the most popular of the early Piedmont blues musicians.

It would be a mistake to think of Lower Chattahoochee blues just as an extension of the Piedmont style because many other elements have coexisted in its musical tradition. For example, Mitchell recorded instrumental dance songs like "Pole Plattin'" and "16–20" that were vestiges of the African American string band tradition. Musicians such as Precious Bryant were heavily influenced by postwar electric blues artists such as Jimmy Reed who were popular on the radio. Lower Chattahoochee blues should not be considered a unique regional sound, but what makes it distinctive is the way in which musicians blended vernacular and popular musical elements.

The blues musicians Mitchell recorded in the Lower Chattahoochee from 1969 until the early 1980s circulated on LPs by small record labels during the 1970s and 1980s. In 2008, Fat Possum released The George Mitchell Collection on CD and LP, which contained the vast majority of Michell's field recordings from the Lower Chattahoochee and elsewhere.

While it is encouraging that the music Mitchell recorded in the Lower Chattahoochee Valley is now available to anyone anywhere, blues scholarship has still not adequately acknowledged this rich musical area. With the exception of Bruce Bastin's Red River Blues, two books (Chattahoochee Album and In Celebration of a Legacy) by the folklorist Fred Fussell, and recent documentary work by the blues guitarist Jontavious Willis, the blues of the Lower Chattahoochee Valley remains largely unappreciated.

This Southern Spaces presentation offers resources that help contextualize Lower Chattahoochee blues, including historical material from Fred Fussell's work and biographical sketches of blues musicians derived primarily from In Celebration of a Legacy. I also present here a selection of George Mitchell's field recordings from 1969 to 1982 courtesy of Fat Possum Records, excellent photographs he took during this same period, excerpts from a video interview I conducted with Mitchell in 2003, and video field recordings I did in 2003. Below, for example, is Precious Bryant performing "My Chaffeur," recorded and popularized by the artist Memphis Minnie in 1941.

The Region

Historian Fred Fussell offers a geographical definition of the Lower Chattahoochee region:

The Lower Chattahoochee River Valley region . . . is marked at its northern end by the point at which the Chattahoochee River, as it flows through the Georgia Piedmont, first touches Alabama. The southern end of the region is designated by the point where it connects with the Flint River at the Florida border. There the two joined rivers become the Appalachicola and flow on southward to the Gulf. East to west the Chattahoochee River's sphere of influence is defined by its watershed—with its thousands of tributaries—the creeks, streams, brooks, and branches which feed it. So defined, the Lower Chattahoochee River valley region is, in essence, the geographical center of the Deep South. There are a total of eighteen counties that lie within the nucleus of the Lower Chattahoochee Valley region—seven in Alabama, eleven in Georgia. The Chattahoochee region begins, in the north, at Troup County in Georgia and Chambers County in Alabama and then runs southward through Lee, Russell, Barbour, Henry, and Dale Counties in Alabama and through Harris, Muscogee, Chattahoochee, Stewart, Quitman, Randolph, Clay, Early, and Decatur Counties in Georgia to end up in Houston County in Alabama and Seminole County in Georgia, both of which border the Florida state line.2Fred Fussell, A Chattahoochee Album: Images of Traditional People and Folksy Places Around the Lower Chattahoochee Valley (Eufala, AL: Historic Chattahoochee Commission, 2000), 1.

Fussell's definition is extremely helpful, but there are numerous blues artists that George Mitchell recorded who were from towns just outside the main eighteen counties. These include Golden Bailey, Cecil Barfield, Jim Bunkley, Jessie Clarence Gorman, Bud Grant, Dixon Hunt, Albert Macon, Green Paschal, Cliff Scott, and Robert Thomas. Because these artists are integral to the regional blues sound, I have stretched the boundaries to include Upson, Talbot, Marion, and Terrell counties in Georgia and Macon County in Alabama.

Fred Fussell offers additional geographical and historical notes in A Chattahoochee Album:

It is believed that Native American people . . . had lived in and around the Lower Chattahoochee River Valley for at least ten thousand years before the intruding Spaniards came here in the late seventeenth century. The very first European settlement in the Chattahoochee Valley was established in 1689 by Spanish monks who, accompanied by a garrison of soldiers assigned to assist them, built the mission and fort of Apalachicola on the west bank of the Chattahoochee River. This site, located in Russell County, Alabama, lies about fifteen miles south of the present-day city of Columbus.3Fred Fussell, Chattahoochee Album, 1–2.

In 1825, with the signing of the infamous Treaty of Indian Springs between the United States and the Creek Nation, the way was opened for the forced final removal of the native people from the region. That done, settlers came here in droves to establish cotton plantations, textile mills, riverboat companies, and all the other retail, supply, and labor services that were needed for the development and support of trade, commerce, industry, and agriculture.4Fussell, 2.

In the past, the river served as the main transportation route that linked regional communities one to another and then out to the larger world. By the middle of the twentieth century, however, the importance of the river as a transportation and commercial link had essentially faded away and had yielded to paved highways, railroads, and air freight.5Fussell, 5.

Masses of country people whose livelihood in the 1930s and early 1940s had been devastated by the woes of the Great Depression left their family farms in Southeast Alabama and headed for the textile communities of Columbus and the other mill towns to the north.6Fussell, 89.

Lower Chattahoochee Blues Artists

Golden Bailey

"Golden Bailey," writes Fussel, "was born sometime before WWI, lived just a few miles east of Geneva, Georgia. During the first half of the twentieth century, that part of west Georgia was a concentrated rural center for a variety of traditional blues and boogie styles including cakewalk tunes, drum and fife bands, play party rounds, and lively dance tunes. While Bailey possessed a somewhat limited repertoire on harmonica, he was an enthusiastic player whose version of the traditional hound dog-fox chase mimic was especially light-hearted and delightfully rendered."7Email communication with the author, August 4, 2020.

Cecil Barfield (aka William Robertson)

Born in 1922 and a farmer until a back injury forced his retirement, Robertson began playing blues at age five on a cooking oil can. "Well, I left the cooking oil can off and put a wire upside of the house," he said, "and I played that with a bottleneck." He began playing guitar when he was twelve, and "started off ragging it, playing them rag pieces" that were traditional to the Chattahoochee Valley.8Liner notes from William Robertson's LP South Georgia Blues. In Jim Pettigrew's article on Georgia blues, "Can' Cha Hear Me Cryin' Ooo-hooo," Barfield states: "'I was listenin' to Bo Miller and some o' them—they were the best around here then—and then I took up the guitar myself. I don't know how many I've worn out since then. There wasn't any radio around here then. We only had record players, you know, the kind that you fold up like a suitcase. It was a long time before there was any radio in these parts. . . . Oh, I used to play a lot. I played for both whites and colored, dances, parties, just about any occasion. There was a few of us and we'd go around all over the country. People were always calling on us. They'd never let me alone.'"[fnLiner notes from William Robertson's LP South Georgia Blues.[/fn]

According to Big Legal Mess Records, "When Mitchell recorded him, Barfield performed interpretations of songs by J.B. Lenoir, Frankie Lee Sims, Little Walter, and Tommy McClennan, as well as several of his own strikingly original compositions. . . . In fear of endangering the welfare checks he relied on for income, Barfield refused to let his real name be used on any of the Mitchell recordings issued in his lifetime; instead, the Barfield recordings issued on labels like Flyright and Southland were done so under the pseudonym William Robertson. . . . Mitchell kept in touch with Barfield up to his death from a heart attack in 1994."9"Cecil Barfield," Big Legal Mess Records, accessed August 5, 2020. https://biglegalmessrecords.com/collections/cecil-barfield.

Precious Bryant

Precious Bryant was born Precious Bussey on January 4, 1942, in Talbot County, just east of Columbus. The third child of nine, with seven sisters and a brother, Bryant was born into a family of traditional musicians who lived in a close-knit community, surrounded by many fine players and singers of traditional blues and gospel.

Bryant recalls a childhood filled with many kinds of homemade music. Her mother was a piano player and an avid singer of church songs. Her father, Lonnie James Bussey, was a traditional blues player. Her uncle, George Henry Bussey, served as her principal mentor and taught her to play bottleneck guitar and to sing the old blues tunes. Several of her male cousins were members of a "fife and drum" group, a rare type of folk band which, with snare drums and homemade "reeds," often paraded and serenaded at community celebrations, fish frys and on holidays around Talbot and Harris counties.

The first instrument Bryant attempted to play was her father's "home guitar," which was so big that the six-year-old could not lift it. She recalls her father placing the guitar in her lap and encouraging his daughter to "take it up" and learn to play. At age nine here skills had advanced to the point that he bought her an instrument of her own—a Silvertone guitar from Sears & Roebuck.

Bryant's early performances were in the Baptist Church. She and her siblings sang spirituals as The Bussey Sisters, with Bryant and one of her older sisters accompanying on guitar. Outside of church, she played at parties and talent shows in and around Talbot County.

Her emerging repertoire was rooted in the traditional sounds of the Lower Chattahoochee, but it also began to reflect the influence of the rhythm and blues and early rock 'n' roll that Bryant heard on the radio. "I listened to Jimmy Reed, Muddy Waters and all them," she explains. "Elmore James and blues like that. I would listen to a song on the radio and write the words down and I wouldn't worry about the music 'cause I could get the music. All I wanted to know was the words."10Precious Bryant, interview, 2003.

"Precious Bryant," adds George Mitchell, "is a Georgia musical treasure. She is one of the last of the living exponents, and certainly still the most active, of a truly wonderful blues tradition that is unique to the southwest region of Georgia. But, unusually, not only is she one of the last—she is no doubt one of the best who ever sang and played this spirited style of blues . . . whether in nearby Columbus, or in Europe, or in Canada, or in New York or Atlanta, Precious Bryant has gotten thousands and thousands of feet tapping . . . to her infectious blend of the old and the new, of the songs of her father and uncle, and of her own compositions, most of which are keeping alive the great and truly unique blues tradition of the Lower Chattahoochee River Valley."

Mitchell first recorded Bryant in 1969. Over a decade later, at his coaxing, she played the Chattahoochee Folk Festival and was an instant hit. Her warm stage presence and lively guitar, combined with her excellent voice, quickly won a devoted audience. Since her Columbus debut, Bryant has performed for scores of audiences in the United States and abroad at such venues as the Blues to Bop Festival in Lugano, Switzerland, the North Georgia Folk Festival in Athens, the Canadian Folk Festival, and the Alabama Folk Festival in Montgomery.

These days Bryant plays mainly at home, with an occasional show in Columbus or Atlanta. To see her play live is a treat. She entices the audience, "Pat your hands together, ain't nobody sick, ain't nobody dead." Along with Bryant's own witty standards, any song she chooses to play is instantly transformed into a moving arrangement stamped with the attitude and assuredness of a true performer.

Precious Bryant is a rarity. Traditional female blues players, especially those as vocally powerful and technically skilled as she, have (to our knowledge) always been few. In the 1930s, Columbus's Ma Rainey became known as the "Mother of the Blues." In a new century, Talbot County's Precious Bryant has secured her place as Georgia's "Daughter of the Blues."11Press bio, Terminus Records.

Jim Bunkley

Born in 1911 in Talbot County, Jim Bunkley started playing music when he was eight. His four brothers and four sisters all oplayed some form of music. An early influence on Bunkley was Blind Lemon Jefferson. Mitchell's liner notes for the Revival Records LP George Henry Bussey and Jim Bunkley, describe his early life and reputation as a musician in Talbot County:

"This album, sadly, is a memorial to Bunkley. He was killed in a head-on collision on a rainy day in October, 1970. I learned of his death about a month later when I visited his home to tell him his recordings were going to be issued. Bunkley lived in a small tar-papered house he bragged was his own, in Geneva, his birthplace. He was eight years old when they took the census in 1920. It was about that time he made friends with the guitar. 'When I was about eight, my brother had one, and me and my nine-year-old sister used to play it. Us couldn't hold it. Had it hangin' up 'side of the wall and we'd get up on the chair and play it. Everyone in my family could play—we had five boys and four girls. We could play fiddles too.' When he got up in age, Bunkley was about the best known musician in Talbot County. He recalled the many times he walked away with prizes offered at the theater in nearby Junction City. 'I was rough then,' he said. 'I had a great big ole cowboy hat and I got up there on stage and cracked a whole lot of jokes and then played. I win all that money too.' Lottie Kate Buckley, Jim's wife, was born October 22, 1918. She sang only two songs for us, but both were superb."12George Mitchell, liner notes for the Revival Records LP George Henry Bussey and Jim Bunkley.

George Henry Bussey

From George Mitchell's liner notes for the Revival Records LP George Henry Bussey and Jim Bunkley:

"George Henry Bussey, a woodworker, lives near Waverly Hall, about fifteen miles from Geneva. He was born in nearby Harris County in 1925. Bussey learned how to play guitar at the age of eighteen. Although he came from a very musical family, he says no one taught him. 'I just always went around to a lot of friend's houses that had gramaphones and listen to different records and catch the sound myself. I listened to a lot of Blind Boy Fuller's records, but I wouldn't try to play it where I learnt the chords.' Until we found him, it had been twelve years since he had played guitar. 'I just got tired of fooling with it,' he said. 'Mine got busted up, wouldn't sound worth nothing, so I just quit fooling with it.' Bussey—a quiet, reserved man—was hesitant to play for us when we asked. But he consented, and some of the pieces of this record were recorded without any practice! But after that first night (we lent him a guitar) he refused to play song for us until he had it just the way he wanted. 'Blues is a feeling,' Bussey says. 'Well, sometimes you get the blues, get 'em on your mind, and you'll feel better when you sing about 'em and just let 'em go on off and let you won't have to worry with 'em no more.'"

George Daniel

Fred Fussell writes in "'Cowboy' George Daniel: Blues Man from Creek Stand": "George Daniel was born in Macon County, Alabama, in 1929. Daniel has been a farmer, a ranch hand, a rodeo cowboy, a timber cutter, and a well digger." Daniel says, 'My daddy was a guitar player. When he quit playing he gave me his guitar. When I was a little boy, I used to set up in the bed and play it. We played for frolics and for house parties all around the community and at fish fries. They played dance music. We never did play any blues before we had a record player. Not in the old times. I learned blues from records. My granddaddy was the fiddle man. I never could do that. I never could use that bow right. We played music at peoples houses. They'd kill a hog and they'd take the livers and lights and all like that and make hash. They'd have a frolic and sell that hash to the people that came to dance.'"13Fussell, Fred. "'Cowboy' George Daniel: Blues Man from Creek Stand," Chattahoochee Tracings: Newsletter of the Historic Chattahoochee Commission, Volume 31, Fall 2003, p. 5.

Cliff Davis

According to Fussel, "Cliff Davis, born in 1913 in Alabama, moved to Stewart County, Georgia, as a small child. He grew up near the county seat of Lumpkin.

As a lifelong sharecropper and tenant farmer, Davis would practice singing field hollers to relieve the tedium of plowing corn, cotton and peanut crops during long hot Summer days."14Email communication with the author, August 4, 2020.

Tom Darby and Jimmie Tarlton

Tom Darby and Jimmie Tarlton were never recorded by Mitchell, but, because Darby lived in Columbus and the duo's 1927 "Columbus Stockade Blues" is a seminal recording, it's worth providing a little context about them here. Tarlton was born in Chesterfield County, South Carolina, in 1892. He traveled extensively around the US in the 1910s and early 1920s and absorbed a wide range of songs and guitar techniques. In the 1920s, he settled in Columbus and teamed up with Tom Darby. Their first commercial recording was for the Columbia label in April 1927. In November of that year, they recorded two more sides for Columbia: "Birmingham Jail" and "Columbus Stockade Blues." The 78rpm record with those two songs was an enormous success, selling almost 200,000 copies. Darby and Tarlton went on to record over sixty sides for three different labels from 1927 to 1933. These feature Tarlton's skillful slide guitar playing, along with Darby's singing and guitar accompaniment. Darby and Tarlton were among several influential white blues artists of this period, including Jimmie Rodgers, Frank Hutchinson, Dock Boggs, and the Delmore Brothers.

Georgia Fife and Drum Band

Bruce Bastin provides excellent information about this group: "Perhaps Mitchell's most interesting discovery was the presence of a fife and drum tradition in the country between Waverly Hall and Talbotton, northeast of Columbus. Until recently it was assumed that the tradition of fife and drum music was uniquely that of north Mississippi around Senatobia. . . . The similarities of the music of the Senatobia and Waverly Hall groups hint that the music was probably more widespread than appreciated. . . . The Georgia fife and drum group was essentially a family band comprising J.W. Jones on bamboo cane fife and his brother James on kettle drum, with the bass drum played by either a younger brother, Willie C. Jones, or a cousin, Floyd Bussey."15Bruce Bastin, Red River Blues: The Blues Tradition in the Southeast (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 151.

Bud Grant

Grant made his first guitar from a poplar tree. Before he was twelve, he played "frolicking" dance music at neighborhood parties. His uncle bought him a Sears Roebuck mail-order guitar for $4.95. He started playing blues in 1940, "learning to play from listening to records." In the following interview, Grant mentions, "I can play a little rock 'n' roll myself now, but I always fancy blues the most."

William Grant

"Born [in 1908] near Pittsview, Alabama" writes Mitchell, "Grant was given a harmonica one Christmas, and he says he learned how to play it while sitting on a plow in the fields. 'I played at parties in the countries. . . . I used to pick guitar, but I come to religion and I put the guitar down. I promised the Lord I wouldn't fool with a guitar no more, but I didn't promise Him I wouldn't fool with a harp. I always keep a harp.'"16George Mitchell, "Notes on the Attached CD Set," In Celebration of a Legacy: The Traditional Arts of the Lower Chattahoochee Valley (Eufala, AL: Historic Chattahoochee Commission, 1999), n.p.

Jimmy Lee and Eddie Harris

"Jimmy Lee Harris," comments Mitchell, "was born in 1935 in Seale, Alabama, about ten miles from his present home of Phenix City. The first instrument he played was the mouthbow, which he made himself when he was nine. His parents bought him a guitar three years later, and he learned to play from a woman named Seesa Vaughn. He and his brother Eddie, who lives in Columbus, still perform at occasional house parties in the area."17George Mitchell, "Notes on the Attached CD Set," In Celebration of a Legacy: The Traditional Arts of the Lower Chattahoochee Valley (Eufala, AL: Historic Chattahoochee Commission, 1999), n.p.

Dixon Hunt

Although biographical information about Dixon Hunt is scarce, he was from Draneville, Georgia, in Marion County, approximately ten miles east of Stewart County. Cliff Scott taught him to play. According to Bruce Bastin, the parochial nature of Hunt's performing territory—little more than sixty miles end to end—was typical of Southeast blues musicians.

Albert Macon

Albert Macon "lived in Macon County, Alabama, where he was born in 1920. He started blowing the harp when he was ten, learning to play the guitar from his father several years later. He played 'set frolics' (couples paid ten cents a set to round dance) and at houseparties and schoolhouses. Robert Thomas was born in 1929, and like Albert Macon, he grew up in Macon County. Thomas began playing blues guitar when he was nineteen or twenty, learning under Albert Macon. Macon and Thomas played together for over four decades until Macon's death in 1993."18George Mitchell, "Notes on the Attached CD Set," In Celebration of a Legacy: The Traditional Arts of the Lower Chattahoochee Valley (Eufala, AL: Historic Chattahoochee Commission, 1999), n.p.

Green Paschal

Born around 1927 in Talbotton, Georgia, Paschal started playing music relatively late, sometime in the 1950s. "I used to play nothing but the blues before I joined the church," he says, "I joined the church about fifteen years [ago] and I quit playing blues. . . . Good old church songs, these old-fashioned songs, I likes 'em. . . . I don't like these jumped up songs that people sing now. . . . I believe in the old way, I just like old songs, the spirit of those old songs."19Green Paschal, interview, 1969.

"Now those songs that they sing now," he continues, "they're all right, them that want to sing 'em, they good, I like to hear 'em singing, but it ain't for me."20Green Paschal, interview, 1969.

Gertrude "Ma" Rainey

Gertrude "Ma" Rainey was several generations older than any of the blues musicians that George Mitchell recorded in the Lower Chattahoochee Valley, and her blues performance style—often featuring accompaniment by jazz and jug bands—was clearly different than the mostly solo, guitar-based blues of the Lower Chattahoochee artists. Nevertheless, because Rainey is such a central figure in the early development of blues and lived a large part of her life in Columbus, it's important to acknowledge her influence here. She was born Gertrude Pridgett in either 1882 or 1886. The house she grew up in at 804 Ninth Street in Columbus was just a few blocks from the First African Baptist Church, where she most likely developed her singing voice.

Rainey began performing in traveling minstrel, tent, and carnival shows around 1900. In an early 1930s interview with the ethnomusicologist John Work III, Rainey notes that she first heard blues at a tent show in a small Missouri town in 1902.21While some of the lyrical qualities of blues had longstanding roots in African American culture, the signature twelve-bar blues form didn't emerge until around 1900. Soon after she began incorporating blues tunes into her stage act, but it wasn't until 1915 when she began to use the word "blues" to advertise her traveling act. With her husband William "Pa" Rainey, she toured extensively with a number of different traveling groups, including the famous Rabbit Foot Minstrels. These groups toured around a reliable circuit of southern cities but also had gigs in northern cities and as far away as Mexico. In 1923, Rainey was recruited by Paramount Records talent scout Mayo Williams. In 1924, she recorded "See See Rider" with a band that included Louis Armstrong and Fletcher Henderson. This song has become a blues standard and has been recorded by best-selling artists like Wee Bea Booze and Elvis Presley. From 1923 to 1928, Rainey cut ninety-four sides for Paramount on their 12000 "race records" series.

As the "Mother of the Blues," Rainey was the most celebrated blues singer of the first three decades of the twentieth century. She was known for her powerful voice, entertaining stage act, and the candid, assertive, and sometimes risqué quality of her lyrics. Many of her songs deal with lost love and betrayals. Angela Y. Davis writes that Ma Rainey "championed the blues in her performances, unafraid to affirm their authority in overt defiance of both the church and the musical traditions of the dominant culture."22 Angela Y. Davis, Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude "Ma" Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday. New York: Vintage Books, 1999), 126. Rainey's songs provide glimpses into African American life during the Jim Crow era, bringing to mind Lawrence Levine's description of the social importance of blues: "The blues insisted that the fate of the individual black man or woman, what happened in their everyday 'trivial' affairs, what took place within them—their yearnings, their problems, their frustrations, their dreams—were important, were worth taking note of and sharing in song. Stressing individual expression and group coherence at one and the same time, the blues was an inward-looking music which insisted upon the meaningfulness of black lives."23Lawrence Levine, Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Thought from Slavery to Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975), 269–270.

Lonzie Thomas

Lonzie Thomas was born in Lee County, Alabama, in 1921.

Describing how he learned to play the guitar, Thomas says, "I watched my daddy's fingers on the guitar and I caught it. He was shot in the face and blinded at the age of 22. 'After I got blind, I got more interested in playing and singing,' he said. 'It was something to keep my mind off worrying.' It was also one of the few ways a blind man could make a living, and he began playing on the streets of Opelika and Columbus for tips and at parties."24George Mitchell, "Notes on the Attached CD Set," In Celebration of a Legacy: The Traditional Arts of the Lower Chattahoochee Valley (Eufala, AL: Historic Chattahoochee Commission, 1999), n.p.

Unknown Blues Artist

Although the identity of this artist remains unknown, his story, recorded here, contributes to the musical history of the Lower Chattahoochee. Born in 1928 and raised in Talbotton, Georgia, he started playing guitar when he was nine years old. Some of the early blues tunes that he learned "came from Blind Boy Fuller." At the end of the clip, he demonstrates "The Buck," an instrumental tune that was played at neighborhood parties and sounds similar to Precious Bryant's "Georgia Buck."

J. W. Warren

Mitchell says that "Warren was born in 1921 in Enterprise, Alabama. In a family of eleven children, he was the only one to take up music, starting at the age of fifteen or sixteen. He entered the military as a young adult and served for fifteen years. While stationed overseas with the military in 1947, he won first prize in a music contest. Returning home, he entered farming and began to play blues at barbeques and house parties in southeast Alabama. 'I came up the hard way, I hadn't had no break whatsoever. . . . I was born in the wrong part of the world and, then again, I didn't go no place to do any better. . . . I got stuck here, and so, this is my home, seeming I can make it better here than I can any place elsewhere.'"

Like many Lower Chattahoochee blues artists, he cites Blind Boy Fuller as a key influence. Warren died on August 5, 2003. Additional recordings by Warren are available through the Music Maker Relief Foundation.

Bud White

Although biographical information on Bud White is difficult to locate, he lived in Stewart County, in Richland, Georgia, and learned to play the song "Sixteen Snow White Horses" from a traveling bluesman from Florida.

Mitchell's recordings of White include "Sixteen Snow White Horses," "Go On Ahead," and "You've Been Gone So Long."

Contexts and Customs

This section highlights characteristic blues songs, the influences of radio and records, and a few notable musical practices of the Lower Chattahoochee Valley.

Lower Chattahoochee Songs

From 1969 until the early eighties, George Mitchell recorded over two dozen Lower Chattahoochee blues artists. The Spotify playlist below compiles Lower Chattahoochee songs he recorded that aren't already included in this presentation. Explore the playlist in a browser, in the Spotify app, or below.

For a full list of the songs George Mitchell recorded in the Lower Chattahoochee region between 1969 and 1982, consult the artist repertoire index, which organizes the songs by artist.

Radio and Records

Records and radio influenced blues musicians in this largely rural region, as Precious Bryant discusses:

Bruce Bastin notes the wide influence of records in Nothing But the Blues: "The traditional folk pattern of passing on music to a younger set was to be enhanced by pure fortuity of circumstance. Traditional folk music could be recorded and heard by thousands, miles away from the home of the recording artist. This enabled a rapid dissemination of music that otherwise could have come only from the slow passage of itinerant artists or the even slower projection of the music from generation to generation."25Bruce Bastin, "Truckin' My Blues Away—East Coast Piedmont Styles" in Nothing But the Blues: The Music and the Musicians, ed. Lawrence Cohn (New York: Abbeville Publishing Group, 1999), 209.

WCLS and WRBL in Columbus were two prominent Lower Chattahoochee blues radio stations from the 1950s through the 1970s. Today, WOKS AM 1340 is the only radio station in the city with daily blues programming.

Musical Customs

Pole Plattin'

In a 2003 interview, George Mitchell discussed a style in the Lower Chattahoochee that he hadn't recognized from previous fieldwork: "They've got a different sound. It's nothing like Mississippi … what I identify as that sound is what Cecil Barfield—who's one of the best I ever recorded—called 'them old rag pieces.' A lot of it seemed to be built around this 'pole plattin'' sound that Cecil did a song on and several people did. They still celebrated Mayday, plattin' the pole, and then they'd have this certain kind of beat, this certain kind of sound…it's a good time sound. There's a lot of fingerpicking along with the strumming in it…Who were the early practitioners to get that sound going? I don't know."

What differentiates this "pole plattin'" style from the standard 1-4-5 blues pattern is that it typically stays in one chord for an extended duration, occasionally goes to the four chord, but never resolves on the five chord. It is also played in an open D or E tuning, which was fairly common among Lower Chattahoochee musicians. According to musician Jake Fussell, the "pole plattin'" style was probably connected to the African American stringband tradition. Early field recordings that most closely resemble "pole plattin'" were made by folklorist John Work with the banjo player Sidney Stripling in 1941 at the Fort Valley State Folk Festival. Stripling was from Kathleen, Georgia, about fifty miles from the eastern boundary of the Lower Chattahoochee Valley.26 Phone interview with Jake Fussell and the author on May 28, 2020.

Buck Dancing

"The term 'buck' is traceable to the West Indies, where Africans used the words 'po bockarau', or 'buccaneer,' to refer to rowdy sailors. Eventually the term came to describe Irish immigrant sailors whose jig dance was known as 'the buck.'"27Dance Teacher Magazine, www.dance-teacher.com.

Buck dancing was popularized in America by minstrel performers in the nineteenth century. The International Encyclopedia of Dance explains, "The old-style African-American buck dance consists essentially of a stamp and slip of the weight-bearing foot backward, often with an incidental toe bounce, with the body leaning forward." Below is a recording of the sounds of buck dancing, with the rhythmic pattern of J.W. and James Jones' feet hitting the floor.

Fife and Drum Music

Writing of his findings and field recordings in 1972, David Evans explains that "[t]he normal combination [of a fife and drum band] is a five-hole cane fife, a snare drum, and a bass drum, but occasionally the fife has six holes or there is a second snare drum. One group I recorded consisted of simply a bass and snare drum without any fife. . . . As early as the seventeenth century [Black people] may have 'picked up' the skills of fife and drum playing from the militia units in New England and the Middle Colonies. . . . During the eighteenth century there are numerous reports of black fifers and drummers."28David Evans, "Black Fife and Drum Music in Mississippi," Mississippi Folklore Register 6 (Fall 1972): 94–95.

"Thomas Jefferson's slaves formed a fife and drum team as their contribution to the War of Independence. . . . Indeed, [Black people] had often been assigned to play military music in early America; one document tells of a black fife and drum corps playing for a Confederate regiment."29Alan Lomax, The Land Where the Blues Began (New York: The New Press,1993), 333.

Folklorist George Mitchell

Retrospect

In the pre-World War II era, some blues musicians traveled from the US South as far as New York City to make commercial recordings, but most cut records at the closest hub, in cities such as Memphis and Atlanta. Blues artists faced major obstacles being able to get to the nearest city to record. Road networks in the 1920s and 1930s remained rudimentary in many areas. It would have been a major personal expense to make a trek of a hundred miles or more to record for relatively little or no pay. Delta and Piedmont artists had more access to their nearest recording hub, via train or car. It's likely that there were musicians as extraordinary as Charley Patton, Skip James, Robert Johnson, and Rev. Gary Davis who were never recorded because access was so limited and few label representatives sought them out.

The Lower Chattahoochee Valley had a vibrant tradition of country blues music in the decades before and after World War II that was neither commercially recorded nor collected by folklorists until George Mitchell began to work there in 1969. Mitchell's field recordings over fifteen years don't provide a comprehensive document of blues in the Lower Chattahoochee Valley, but they do attest to the quality and breadth of the repertoire. And while there may not be a distinctive blues sound and style from this region, musicians in the Lower Chattahoochee blended and adapted various forms of vernacular and popular music for their largely rural audiences.

Publication Update

In 2020, Southern Spaces updated this publication as part of the journal's redesign and migration to WordPress. Updates include layout changes to improve navigability; audio, image, slideshow, and text link adjustments; and revised recommended resources, tags, and related publications. For access to the original layout, paste this publication's URL into the Internet Archive: Wayback Machine and view any version that predates January 2019.

Recommended Resources

Text

Davis, Angela Y. Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude "Ma" Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday. New York: Vintage Books, 1999.

McGinley, Paige A. Staging the Blues: From Tent Shows to Tourism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014.

Mitchell, George. Mississippi Hill Country Blues 1967. American Made Music Series. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2013.

Palmer, Robert. Deep Blues. New York: Viking Penguin, 1981.

Whiteis, David. Southern Soul-Blues. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Web

Ferris, Bill, David Evans, and Judy Peiser. "Gravel Springs Fife and Drum." 1972. Short film. Available at Folkstreams. https://www.folkstreams.net/film-detail.php?id=59.

Hedin, Benjamin. “Picking up the Piedmont Blues.” Oxford American: A Magazine of the South 95 (2016). https://www.oxfordamerican.org/magazine/item/1047-picking-up-the-piedmont-blues.

Keyes, Jessica. “The Country Blues.” Folkways. Accessed February 4, 2020. https://folkways.si.edu/country-blues-rural-soul-southern-usa/music/article/smithsonian.

Mitchell, George. “Hoot Your Belly.” By Brian Crews. Oxford American: A Magazine of the South (December 2015). https://www.oxfordamerican.org/item/725-hoot-your-belly.

Rock On Away From Here: The Blues in Georgia’s Lower Chattahoochee Valley, Documentary, directed by Brian Crews. Carrolton: University of West Georgia Center for Public History, 2016. https://uwgcph.org/rock-on/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Evans, David. "The Development of the Blues." Chapter. In The Cambridge Companion to Blues and Gospel Music, edited by Allan Moore, 20–43. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Fred Fussell, A Chattahoochee Album: Images of Traditional People and Folksy Places Around the Lower Chattahoochee Valley (Eufala, AL: Historic Chattahoochee Commission, 2000), 1. |

| 3. | Fred Fussell, Chattahoochee Album, 1–2. |

| 4. | Fussell, 2. |

| 5. | Fussell, 5. |

| 6. | Fussell, 89. |

| 7. | Email communication with the author, August 4, 2020. |

| 8. | Liner notes from William Robertson's LP South Georgia Blues. |

| 9. | "Cecil Barfield," Big Legal Mess Records, accessed August 5, 2020. https://biglegalmessrecords.com/collections/cecil-barfield. |

| 10. | Precious Bryant, interview, 2003. |

| 11. | Press bio, Terminus Records. |

| 12. | George Mitchell, liner notes for the Revival Records LP George Henry Bussey and Jim Bunkley. |

| 13. | Fussell, Fred. "'Cowboy' George Daniel: Blues Man from Creek Stand," Chattahoochee Tracings: Newsletter of the Historic Chattahoochee Commission, Volume 31, Fall 2003, p. 5. |

| 14. | Email communication with the author, August 4, 2020. |

| 15. | Bruce Bastin, Red River Blues: The Blues Tradition in the Southeast (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 151. |

| 16. | George Mitchell, "Notes on the Attached CD Set," In Celebration of a Legacy: The Traditional Arts of the Lower Chattahoochee Valley (Eufala, AL: Historic Chattahoochee Commission, 1999), n.p. |

| 17. | George Mitchell, "Notes on the Attached CD Set," In Celebration of a Legacy: The Traditional Arts of the Lower Chattahoochee Valley (Eufala, AL: Historic Chattahoochee Commission, 1999), n.p. |

| 18. | George Mitchell, "Notes on the Attached CD Set," In Celebration of a Legacy: The Traditional Arts of the Lower Chattahoochee Valley (Eufala, AL: Historic Chattahoochee Commission, 1999), n.p. |

| 19. | Green Paschal, interview, 1969. |

| 20. | Green Paschal, interview, 1969. |

| 21. | While some of the lyrical qualities of blues had longstanding roots in African American culture, the signature twelve-bar blues form didn't emerge until around 1900. |

| 22. | Angela Y. Davis, Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude "Ma" Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday. New York: Vintage Books, 1999), 126. |

| 23. | Lawrence Levine, Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Thought from Slavery to Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975), 269–270. |

| 24. | George Mitchell, "Notes on the Attached CD Set," In Celebration of a Legacy: The Traditional Arts of the Lower Chattahoochee Valley (Eufala, AL: Historic Chattahoochee Commission, 1999), n.p. |

| 25. | Bruce Bastin, "Truckin' My Blues Away—East Coast Piedmont Styles" in Nothing But the Blues: The Music and the Musicians, ed. Lawrence Cohn (New York: Abbeville Publishing Group, 1999), 209. |

| 26. | Phone interview with Jake Fussell and the author on May 28, 2020. |

| 27. | Dance Teacher Magazine, www.dance-teacher.com. |

| 28. | David Evans, "Black Fife and Drum Music in Mississippi," Mississippi Folklore Register 6 (Fall 1972): 94–95. |

| 29. | Alan Lomax, The Land Where the Blues Began (New York: The New Press,1993), 333. |