Overview

In an excerpt from Medicine and Nation Building in the Americas, 1890–1940 (Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 2015), author José Amador discusses the transmission of new medical knowledge from Puerto Rico to the United States as it circulated from US military doctors through local physicians to hookworm patients. Amador argues that this flow represents two significant public health crossings that not only illustrate the extent that physicians and patients shaped, and were shaped, by the hookworm campaign, but also demonstrate the linkages between colonial medicine and US public health philanthropy.

Public Health in the US and Global South is a collection of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications examining the relationship between public health and specific geographies—both real and imagined—in and across the US and Global South. These essays raise questions about the origin, replication, and entrenchment of health disparities; the ways that race and gender shape and are shaped by health policy; and the inseparable connection between health justice and health advocacy. Selected from a competitive group of submissions, these pieces offer new perspectives on the multiple meanings of health, space, and the public in the US and Global South. The series editor for Public Health in the US and Global South is Mary E. Frederickson.

Public Health Crossings

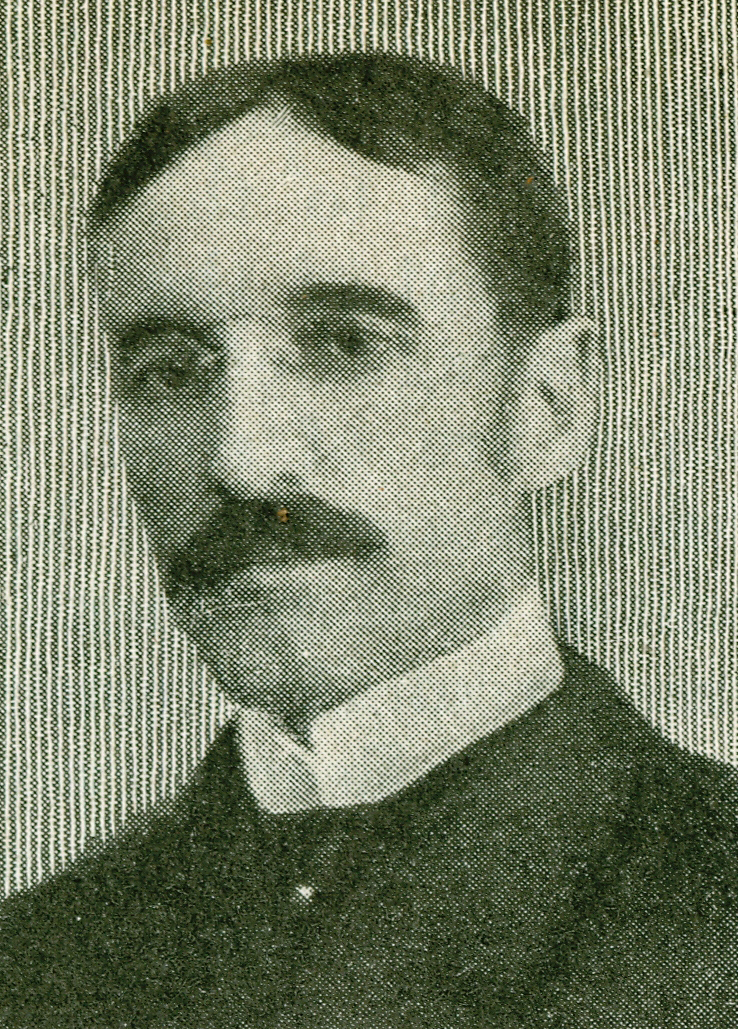

Top, Colonel Bailey K. Ashford, ca. 1893. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in public domain. Bottom, William H. Hunt, Governor of Puerto Rico, 1901–1904. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in public domain.

Nearly a year before Finlay's mosquito theory was finally confirmed in Cuba, a US physician discovered in Puerto Rico the source of the pervasive anemia that had afflicted the population for more than a century. On August 10, 1899, Bailey K. Ashford, then a young post surgeon of the US Army, revealed that hookworm caused the mysterious weakness and extreme pallor that he had observed in peasants for nearly a year.1The broad term "peasant" includes the diverse farmers and laborers of Puerto Rico's mountainous coffee region. This operational definition is not meant to override social and property distinctions within the region. See Sidney Mintz, "A Note on the Definition of Peasantries," Journal of Peasant Studies 1 (1973): 91–106. See also Frederick Cooper, Allen F. Isaacman, Florencia E. Mallon, William Roseberry, and Steve J. Stern, Confronting Historical Paradigms: Peasants, Labor, and the Capitalist World System in Africa and Latin America (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1993). Ashford was not the first fascinated by the mysterious affliction; for decades physicians and intellectuals in Puerto Rico had made it the central concern of essays and novels. Unlike yellow fever in Cuba, hookworm was not characterized by dramatic seasonal outbreaks in port cities. Instead, it was a sluggish disease endemic in the island's mountainous interior. Whereas in Cuba most yellow fever victims were nonimmune Spanish immigrants, in Puerto Rico most hookworm victims were peasants—commonly known as jíbaros—whose families had harbored the disease for generations. Moreover, whereas the control of yellow fever required killing the mosquito vector and eliminating its breeding places, the control of hookworm disease required direct medication of patients.

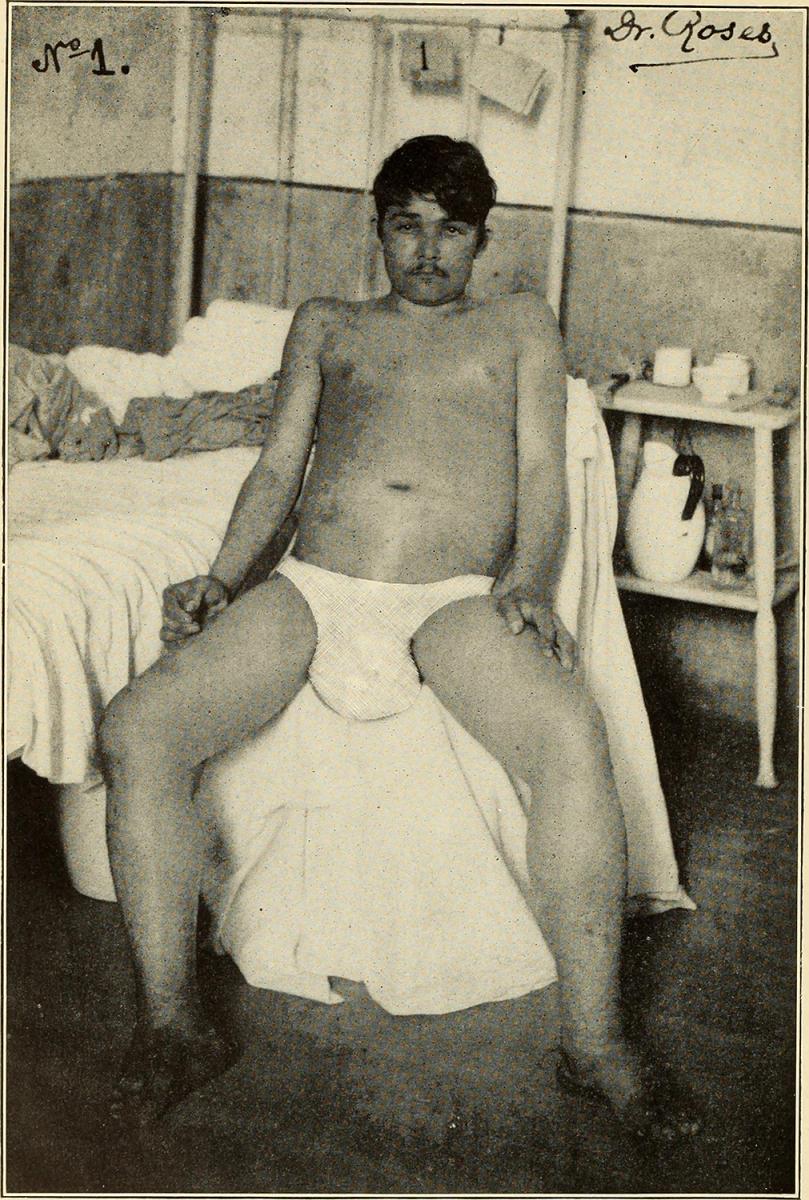

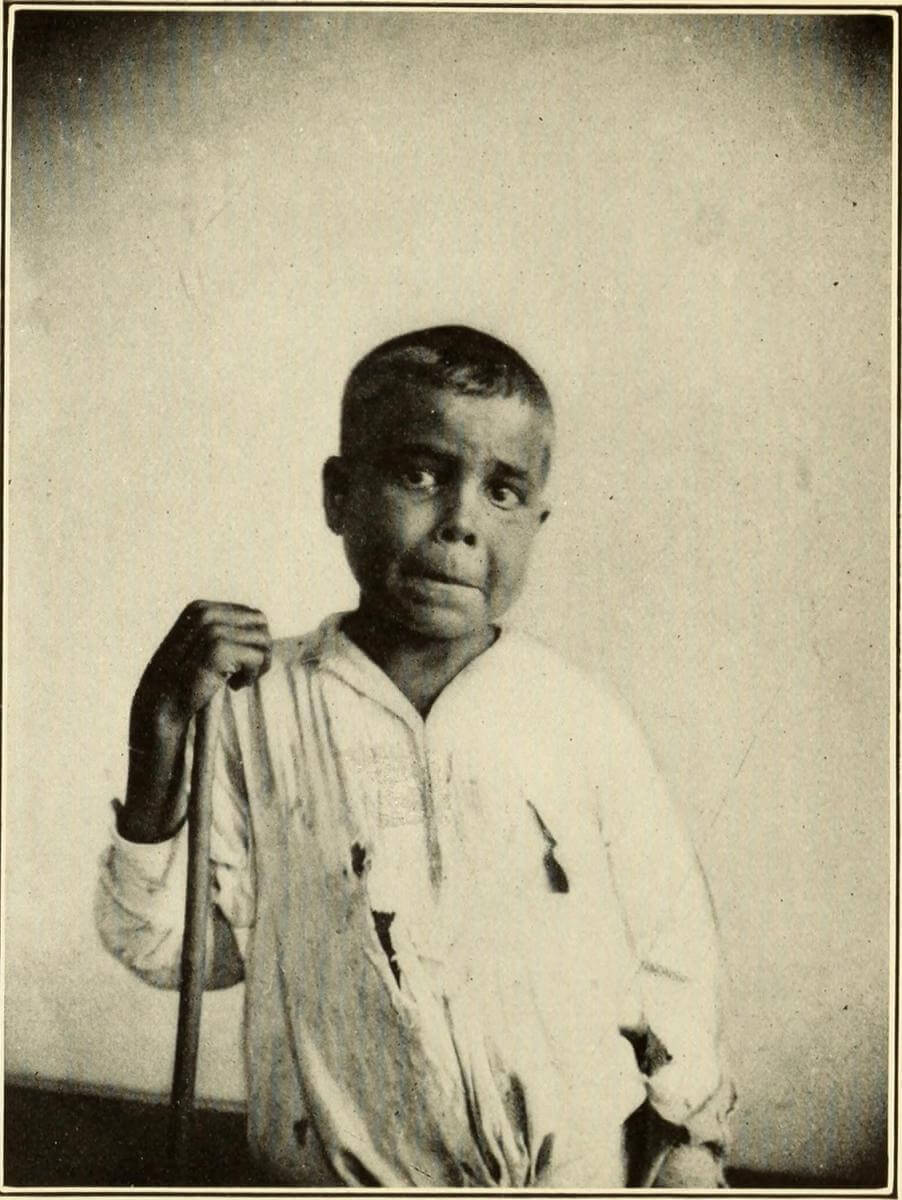

Like many young physicians of the era, Ashford was intensely curious about tropical diseases—a fixation that led him to link anemia to hookworm after he examined the stool sample of a jíbaro in the microscope.2Bailey K. Ashford, A Soldier in Science: The Autobiography of Bailey K. Ashford (San Juan: Editorial de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, 1998 [1934]), 3. Aware of the historical consequences of his discovery, he rushed his patient to the "local photographer to immortalize him," turning the Puerto Rican jíbaro into the "prototype of anemic millions all over the Caribbean, all over the tropical belt that girdles the portly belly of Mother Earth."3Ibid., 5.

If Ashford's photographic record connected the jíbaro to hookworm sufferers around the world, at a local level public and financial support for initiating an anti-hookworm campaign was far from secure. After several years of frustration seeking support, Ashford finally found a sponsor in Governor William H. Hunt, one of the leading figures in organizing the new civil government of Puerto Rico. In 1904, his administration allocated funds to establish the Puerto Rico Anemia Commission, launching the first large-scale campaign to study and treat hookworm disease in the hemisphere.4William H. Hunt, Message of the Honorable William H. Hunt to the Second Legislative Assembly (San Juan: Bureau of Printing and Supplies, 1904), 20–21. With its emphasis on testing for hookworm, preventing soil pollution, and offering pharmaceutical control, the commission rendered visible the vast population suffering from hookworm disease. As the campaign gained popularity, anemia ceased to be a disease in its own right; instead, it became a symptom of what doctors referred to as hookworm disease, or uncinariasis. As the architect of the campaign, Ashford recruited prominent Puerto Rican doctors, including Pedro Gutiérrez Igaravídez, Francisco Sein, Agustín Stahl, and Francisco del Valle Atiles, to collaborate with the commission. Through their efforts thousands of peasants were introduced into the realm of medicine and institutional health care.

Bailey K. Ashford immortalized his first hookworm patients in a photograph. The caption reads: "Photograph of a number of natives of Puerto Rico, showing pernicious anemia due to Ankylostoma duodenale." Source: Bailey K. Ashford, "Report to the Surgeon General," December 22, 1899, Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine, RG 2.3, box 10. Originally published in José Amador's Medicine and Nation Building in the Americas, 1890–1940 (Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 2015). Courtesy of Vanderbilt University Press.

Despite the crucial significance of Puerto Rico in the development of US public health, the place that this campaign occupies in the history of US tropical medicine and international philanthropy has been underappreciated.5One notable exception is Nicole Trujillo-Pagán, Modern Colonization by Medical Intervention: US Medicine in Puerto Rico (Boston, MA: Brill, 2013). For hookworm disease in Puerto Rico, see Francisco A. Scarano, "Desear el jíbaro: Metáforas de la identidad puertorriqueña en la transición imperial," Illes i imperis 2 (1999): 65–74; José Quiroga, "Narrating the Tropical Pharmacy," in Puerto Rican Jam: Essays on Culture and Politics, edited by Frances Negrón-Muntaner and Ramón Grosfoguel (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), 116–26; and Fernando Feliú, "Rendering the Invisible Visible and the Visible Invisible: The Colonizing Function of Bailey K. Ashford's Antianemia Campaigns," in Foucault and Latin America: Appropriations and Deployment of Discursive Analysis, edited by Benigno Trigo (New York: Routledge, 2002), 153–68. Despite its contribution, this literature focuses mostly on imperial discourses and practices, not on the popular responses to the hookworm campaign or its transnational implications. In many ways, Ashford's accomplishments have been overshadowed by the yellow fever work of Carlos Finlay, Walter Reed, and William C. Gorgas in Cuba. Moreover, relative to the historical understanding of hookworm campaigns in the US South, Costa Rica, Brazil, the Philippines, and Mexico, the campaign in Puerto Rico has earned little more than a footnote in standard accounts of US public health history.6On hookworm eradication in the US South, see John Ettling, The Germ of Laziness: Rockefeller Philanthropy and Public Health in the New South (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981); and Matt Wray, Not Quite White: White Trash and the Boundaries of Whiteness (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 96–132. On Costa Rica, see Steven Palmer, From Popular Medicine to Medical Populism: Doctors, Healers, and Public Power in Costa Rica, 1800–1940 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 155–82. On Brazil, see Gilberto Hochman, A era do saneamento: As bases da política de saúde pública no Brasil (São Paulo: Editora Hucitec, 1998). On Mexico, see Anne-Emanuelle Birn, Marriage of Convenience: Rockefeller International Health and Revolutionary Mexico (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2006), 61–116. On the Philippines, see Warwick Anderson, Colonial Pathologies: American Tropical Medicine, Race, and Hygiene in the Philippines (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 104–29. Yet this campaign, like no other, was the first that raised public awareness about the disease and served as a model for hookworm eradication campaigns worldwide. To date, too few have paid close attention to the haphazard process that helped build this campaign, the people who sought treatment, and the role of Puerto Rico in launching Rockefeller philanthropic public health initiatives. Integrated into one history, these public health crossings illuminate overlapping stories of colonial agency and imperial rule, of peasants and physicians coming to understand hookworm disease in view of each other, and of the transformation of the Puerto Rico campaign as a model for stemming the disease in the rest of the tropical world.

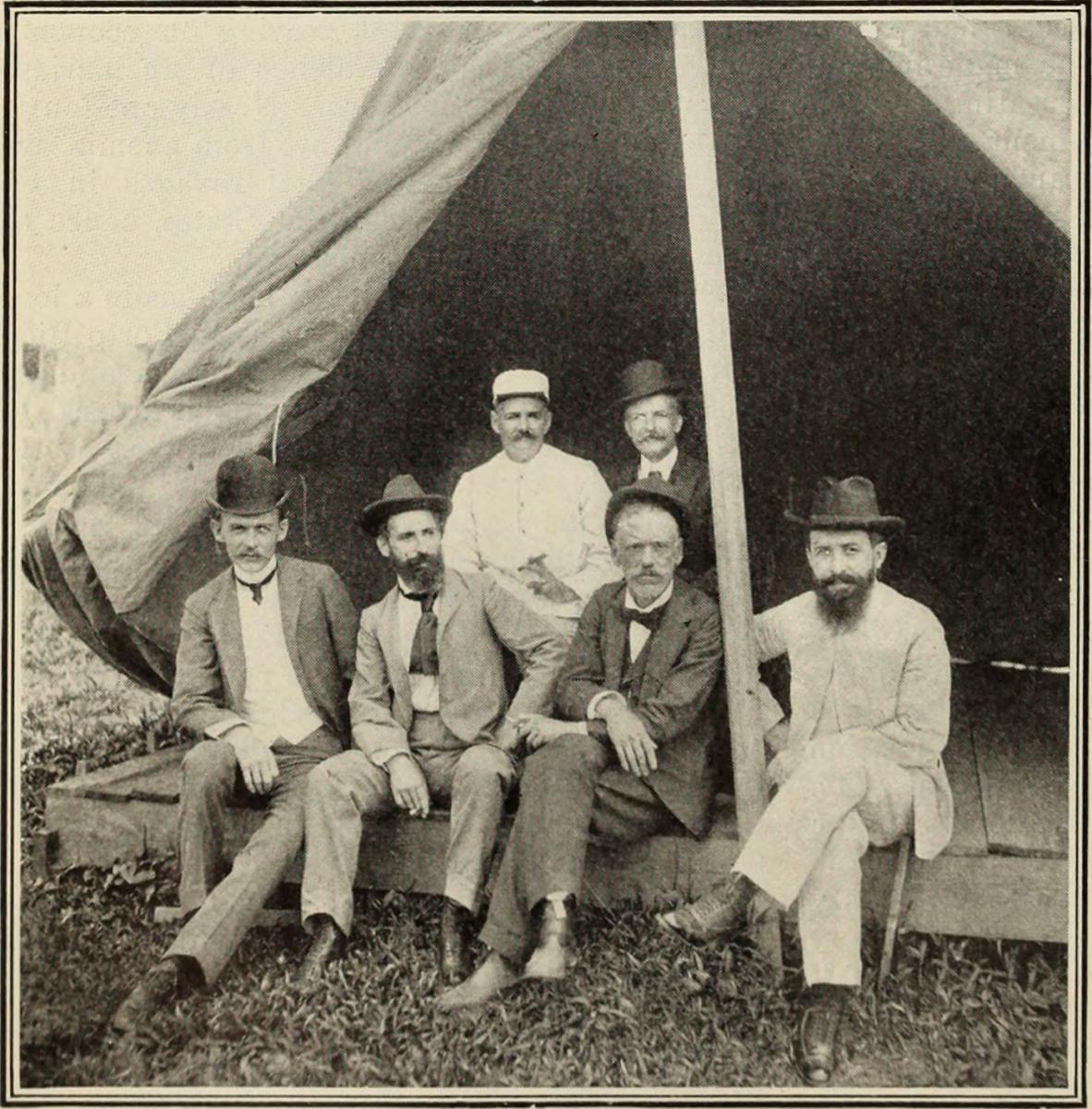

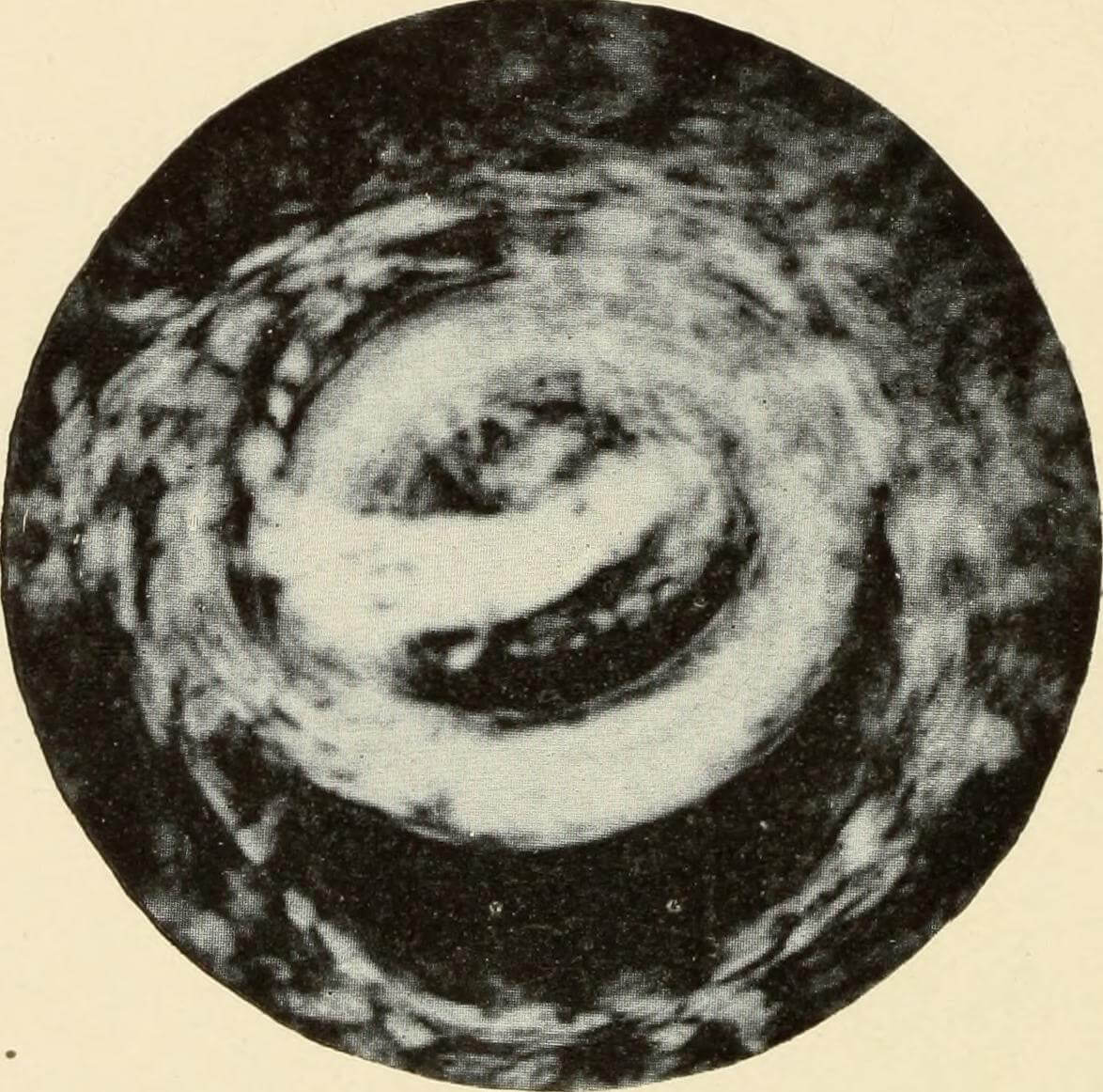

Top, Group of United States Government and Native Physicians, including Dr. Bailey K. Ashford, Puerto Rico, ca. 1890. Image courtesy of Flickr user Internet Archive Book Images. Image is in public domain. Bottom, Medical Illustration of uncinaria Americana. Illustration originally published in Diagnostic methods, chemical, bacteriological and microscopical: a text-book for students and practitioners (Philadelphia: P. Blakiston's Son & Co., 1909), 192. Image uploaded by Flickr user Internet Archive Book Images. Image is in public domain.

That the story of Ashford and Puerto Rico's hookworm campaign remains mostly hidden is hardly surprising considering the place they occupy in the history of imperial medicine. Four factors in particular explain this lack of attention. First, the battle between Ashford, the physician, and Charles W. Stiles, the zoologist, to identify and name the intestinal parasite that causes the disease was won by Stiles. Working with a hookworm specimen provided by Ashford, in 1902 Stiles found that the parasite belonged to a new species, Uncinaria americana, although later he changed the name to the more sensational Necator americanus (American Killer).7For the nomenclature dispute between Ashford and Stiles, see Ettling, Germ of Laziness, 29–33. Second, Ashford's life does not fit the traditional historiography of empire since he was not the conventional emissary of the white man's burden or US imperialism.8José Rigau, "Bailey K. Ashford, más allá de sus memorias," Puerto Rico Health Sciences Journal 19, no. 1 (2000): 51–55. On the contrary, in 1899, the same year he "discovered" the cause of anemia, he married María Asunción López, daughter of the island's first newspaper publisher, and from then on devoted himself to curing the afflicted. He spoke and wrote fluently in Spanish, and, despite the paternalistic tone of his words, he frequently and genuinely praised the work, wits, and moral compass of the peasants he treated. He raised his children in Puerto Rico, and remained on the island off and on until his death in 1934. Third, while Puerto Rico was indeed a colonial laboratory, in the early decades of the twentieth century the island was represented as a docile counterexample to Cuba and the Philippines, and today it remains politically linked to the United States; these facts have tended to make historians of imperial medicine less interested in the campaign. Finally, shortly after the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission took up Ashford's ideas for eradicating hookworm, a new rhetoric of public health efficiency and rigor declared the Puerto Rican model expensive and unreliable. Hence, to rediscover the significance of the campaign initiated in the colonial periphery, it is first necessary to restore the influence that the Puerto Rican campaign once enjoyed.

Paying close attention to the development of the Puerto Rican campaign in the context of expanding US imperial medicine highlights its significance beyond its local success. The campaign came into existence through the interactions of new colonial administrators, US and Puerto Rican health specialists, and the inhabitants of the mountainous coffee region. As Paul A. Kramer has pointed out, "colonial dynamics are not strictly derivative of, dependent on, or respondent to metropolitan forces," but are instead part of a dense network of forces that continuously remake each other.9Paul A. Kramer, "Race, Empire, and Transnational History," in Colonial Crucible: Empire in the Making of the Modern American State, edited by Alfred W. McCoy and Francisco A. Scarano (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009), 199–209. While many Puerto Rican elites participated actively in building the infrastructure envisioned by the commission, others oriented their efforts toward civic organizations disseminating hookworm information or toward opposing the campaign based on their political alliances. In addition, popular participation often pushed municipal and colonial officials to establish treatment stations, rather than simply to respond to the US disciplinary strategies. Peasants, for example, appropriated specific elements of colonial rule that most directly benefited their health interests, and rejected those that did not. Across the Atlantic, US physicians followed closely events unfolding in Puerto Rico to assess the political and medical impact of this health intervention among the white rural poor. In this field of exchanges and possibilities where new ideas about the disease and its cure emerged, the boundaries between colonial possession and the imperial state blurred, and new medicalized stereotypes about populations were forged, transformed, and contested.

Hookworm (Extract from Review of Program presented to Scientific Directors), 1942. Memo by Rockefeller Foundation. Courtesy of the 100 Years: The Rockefeller Foundation website, Rockefeller Archive Center, Rockefeller Foundation.

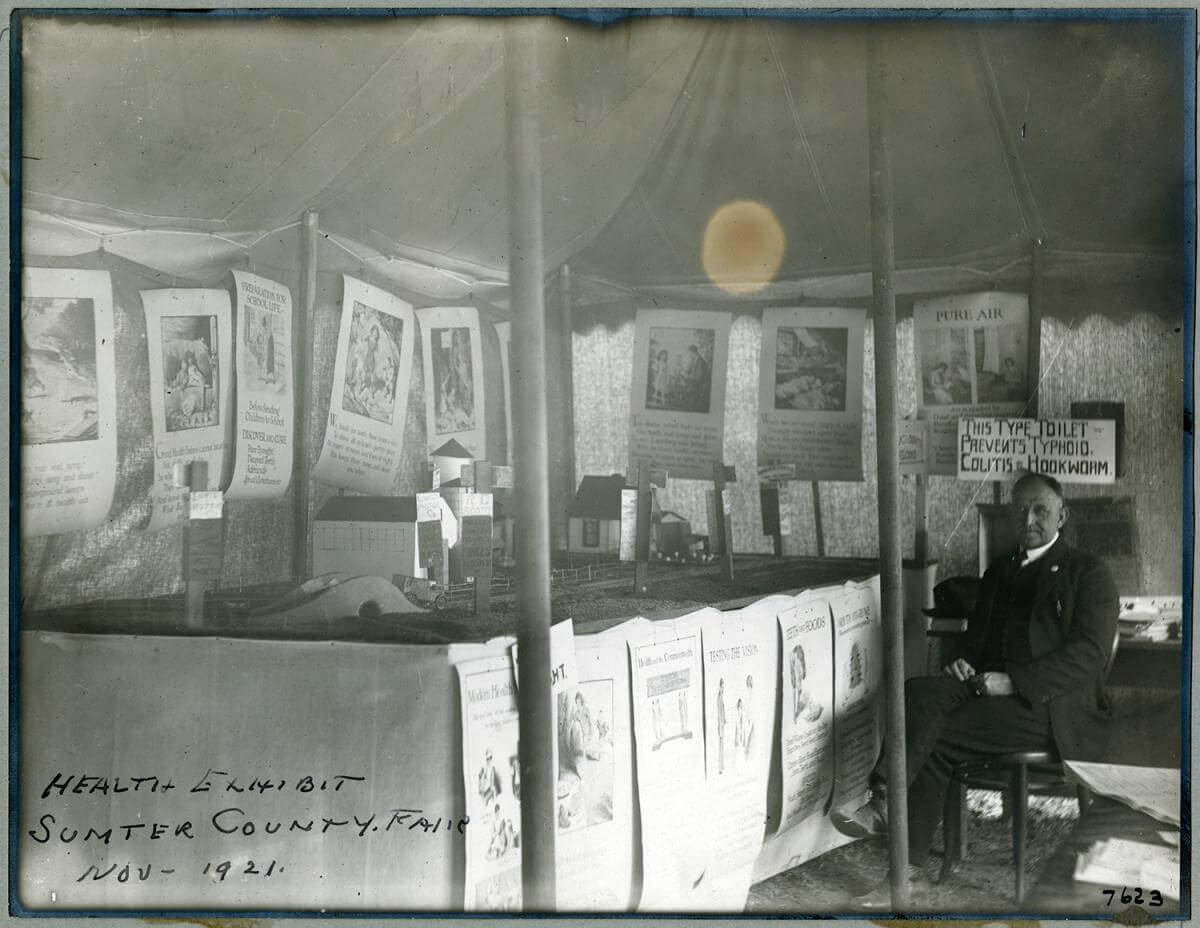

This chapter interprets the back-and-forth flow of new medical knowledge from US military doctors through local physicians to hookworm patients and from Puerto Rico to the United States as evidence of two significant public health crossings. The first crossing illustrates the extent that physicians and patients shaped, and were shaped, by the hookworm campaign. This campaign is remarkable because its complete novelty to the medical community and the mountainous dweller led to creative interactions that shaped the flow of information and popular expectations.10For the interplay of elite and popular responses to the United States, see Eileen J. Suárez Findlay, Imposing Decency: The Politics of Sexuality and Race in Puerto Rico, 1870–1920 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999), 110–34. The second crossing demonstrates the linkages between colonial medicine and US public health philanthropy. Years of exchanges between colonial officials, physicians, and journalists made Puerto Rico a constant point of reference among the US physicians and the public at large. When in 1909 the Rockefeller Foundation decided to undertake the hookworm program in the US South, the image of tens of thousands of redeemed Puerto Ricans was not too far from the minds of its staff. Their focus would be to adapt the lessons of the colonial laboratory to the United States.

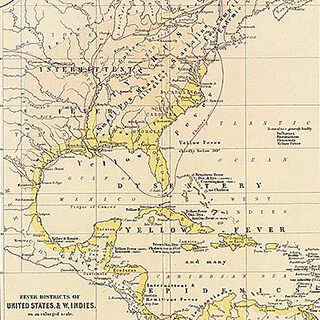

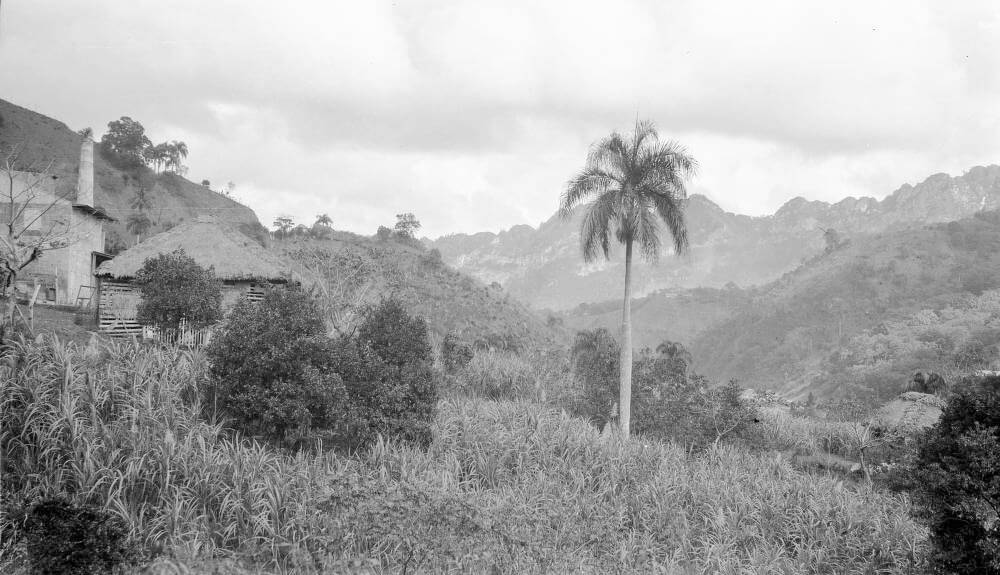

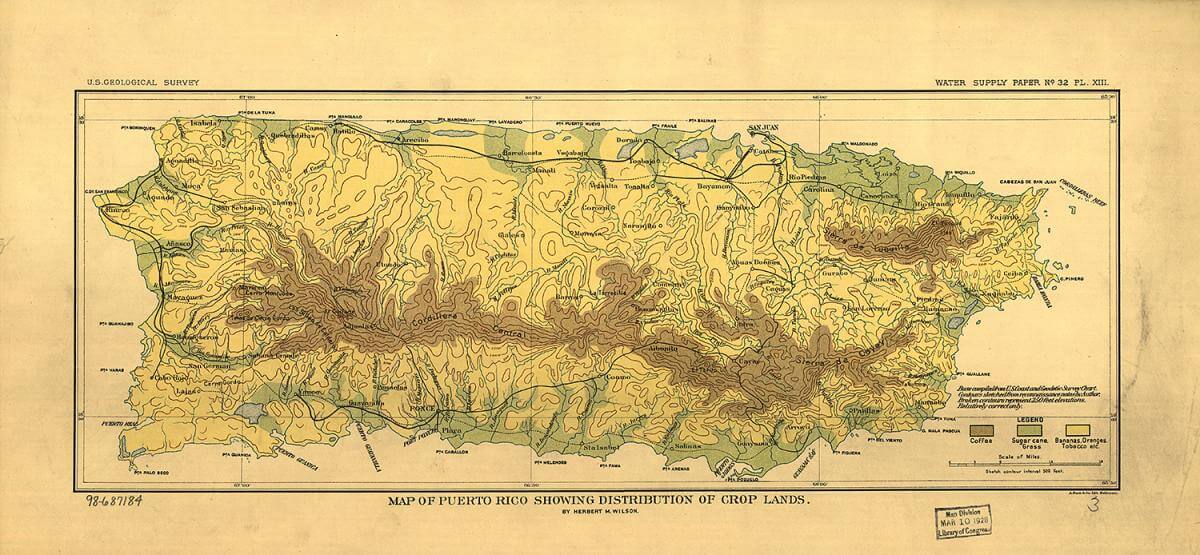

Hookworm in the Coffee Region

During the second half of the nineteenth century, the increased cultivation of coffee in Puerto Rico's central mountain range generated favorable conditions for hookworm infestation. By the 1870s, the coffee grown in the highlands had become the island's principal agricultural export, surpassing the sugar produced in the coastal zones. In the next two decades, coffee production nearly tripled, accounting for more than 75 percent of the value of Puerto Rico's gross export. The expansion of large coffee estates in the highlands and the attendant impoverishment of small landholders resulted in an increased number of landless families. Peasants in turn were forced to become renters or agregados (service tenants), joining the growing number of wage laborers on coffee plantations. Fueled by the coffee boom, highland migration soared and for the first time the central mountainous region displaced the coast as the most densely populated area of Puerto Rico.11For the coffee boom in nineteenth-century Puerto Rico, see Laird W. Bergad, Coffee and the Growth of Agrarian Capitalism in Nineteenth-Century Puerto Rico (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983), especially chapter 4. By the time the United States invaded Puerto Rico in 1898, 63 percent of its 953,243 inhabitants were peasants living in the coffee region.12Irene Fernández Aponte, El cambio de soberanía en Puerto Rico: El otro '98 (Madrid: Editorial Mapfre, 1992).

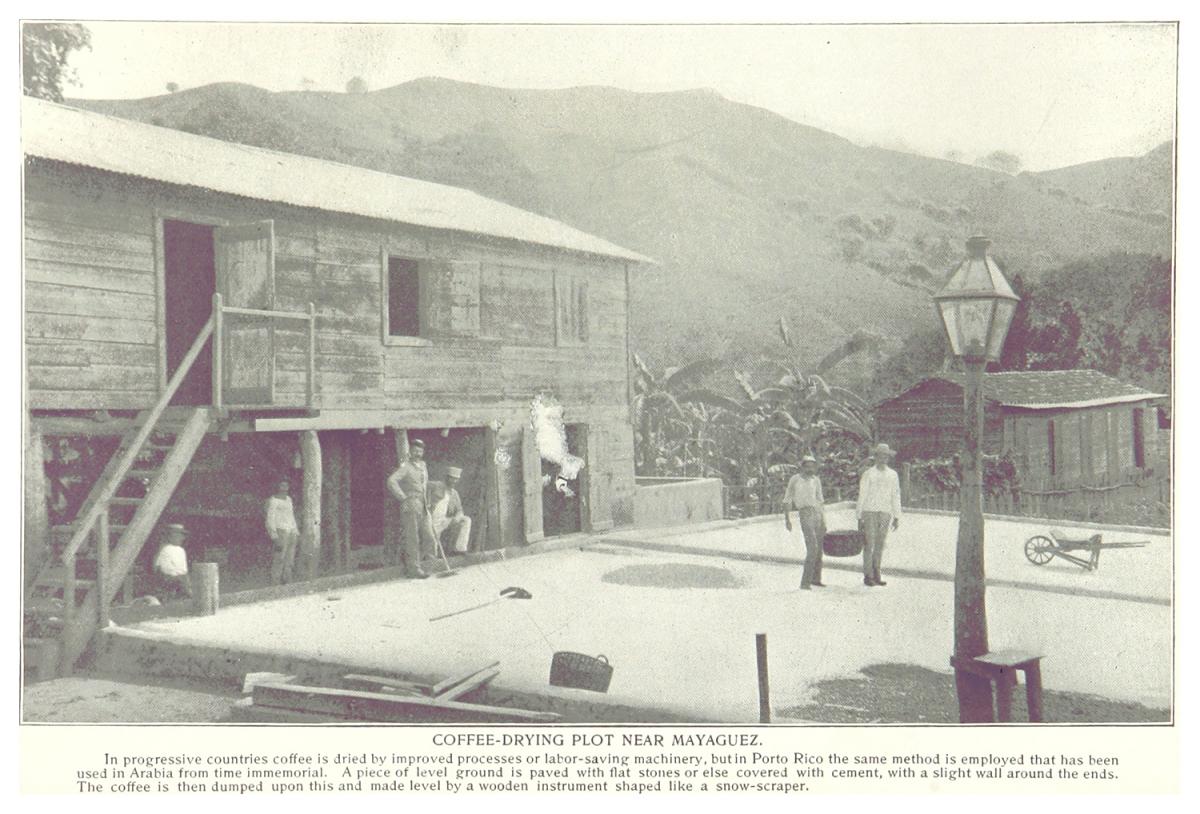

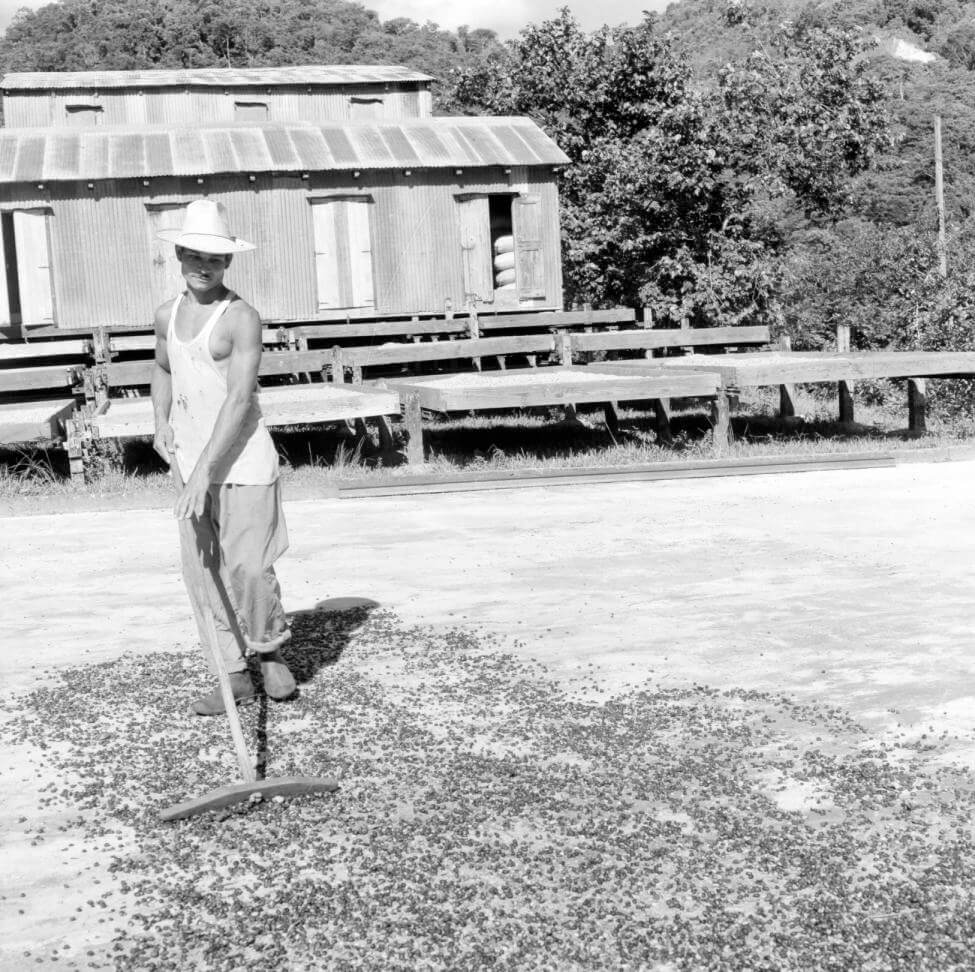

Top, Coffee-Drying Plot near Mayaguez, Puerto Rico, 1899. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in public domain. Middle, Botanical illustration of coffea arabica, 1794. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in public domain. Bottom, Coffee Plantation, Puerto Rico, 1899. Originally published in Frederick A. Ober, Puerto Rico and Its Resources (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1899). Photograph uploaded by Flickr user Internet Archive Book Images. Image is in public domain.

The generalized misery of landless peasants and the cyclical nature of work in coffee plantations favored hookworm infestation. Coffee picking generally began during the rainy season, the period between the months of June and November. Migrant laborers frequently harvested coffee under pouring rain, moving from plantation to plantation looking for work as the bean matured in different localities. The hookworm larvae, like the coffee variety grown in the region (Coffea arabica), thrived on rain, humidity, and protection from direct sun. It was under the shade of trees such as guamá, moca, capá prieto, and the búcare that the laboring men, women, and children picked the matured bean, and their bare feet would come into contact with soil polluted by feces, which harbored hookworm larvae. The larvae then entered between the soft skin of the toes, passed through the bloodstream to the lungs, and traveled from there to the throat, stomach, and finally to the intestines, where it colonized the intestinal lining. As the day passed, the worker would experience an itching sensation between his or her toes, and by the next day, an unbearable dermatitis—commonly known as mazamorra—would develop. Once in the intestinal lining, the hookworm could live for up to ten years. The female parasite in the intestines reproduced rapidly, releasing thousands of eggs through the feces to hatch in the moist soil and reinitiating the infection cycle. The simple harboring of the worms, however, did not immediately provoke symptoms. Symptoms were directly proportional to the intensity of the infection. In normal adults, a moderate infection might cause pallor, nausea, and anemia, whereas a severe infection entailed a series of digestive and nervous disorders that could lead to death. In children, moderate to severe infections could impair mental and physical development.13James J. Plorde, "Hookworms," in Sherris Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases, edited by Kenneth J. Ryan and C. George Ray (Norwalk, CT: Appleton and Lange, 2010), 844–46.

Years of seasonal labor and shifting patterns of migration resulted in a hookworm epidemic that mostly afflicted the population of the coffee region. The intensity and scope of hookworm infestation depended on the contingent forces of poverty and environmental vulnerability. The virtual absence of public health infrastructure and the lack of outhouses on coffee plantations contributed to the situation. "Uncinariasis has its great breeding place in the coffee plantations of Porto Rico," the two leading doctors of the eradication campaign reported, "and here a barefooted people pollute the soil and are infected and reinfected by it until the life of every man, woman, and child is punctuated by a vast number of reinfections."14Bailey K. Ashford and Pedro Gutiérrez Igaravídez, Uncinariasis in Porto Rico: A Medical and Economic Problem (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1911), 11. Ashford's diagnosis in 1899 laid the groundwork for a new colonial pact that increasingly made the state responsible for the protection and well-being of the population in the coffee region. Public health advocates invoked the figure of the jíbaro to move beyond the relief work of private charity to develop a centralized public health infrastructure.15On nineteenth-century charity work, see Teresita Martínez Verge, Shaping the Discourse on Space: Charity and Its Wards in Nineteenth-Century San Juan, Puerto Rico (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1999).

This centralizing goal built on an ideology of excess and discipline that connected the anemic peasant to other social maladies. As noted in Chapter 1, in the second half of the nineteenth century, narratives of caution linked the disease's symptom to an endless number of excesses—from alcohol abuse to a lack of work ethic to sexual promiscuity—that enervated the human body and paved the way for the feebleness so common among the inhabitants of the highlands. Doctors, writers, and journalists popularized the idea that the widespread feebleness of peasants was not only the result of inadequate nutrition, poor housing, and lack of hygiene, but also of racial mixing and the tropical environment. Francisco del Valle Atiles, for example, wrote a lurid sociological tract about the reprehensible lives of peasants, warning about the possibility of social dissolution. In El campesino puertorriqueño (The Puerto Rican Peasant; 1887), he complained that Puerto Rico's path toward progress was hindered by the "lack of vitality" of the jíbaro and an overabundance of "incapable arms" in agricultural enterprises.16Francisco del Valle Atiles, El campesino puertorriqueño: Sus condiciones físicas, intelectuales y morales, causas que determinan y medios para mejoralas (San Juan: Tipografía de González Font, 1887), 8. The mobilization of these narratives served in part to forge consensus about the need to transform the peasant population into a citizenry capable of hygienic regulation and regimented work before it could be included as part of a broad political base.17See Astrid Cubano-Iguina, "Political Culture and Male Mass-Party Formation in Late-Nineteenth-Century Puerto Rico," Hispanic American Historical Review 78, no. 4 (1998): 631–62.

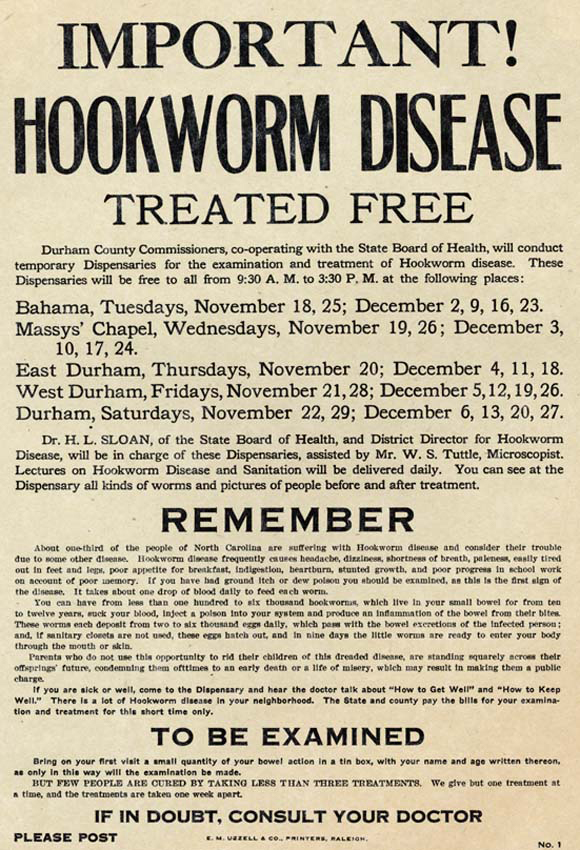

Hookworm Treatment broadside, Durham, North Carolina, ca. 1913. Broadside by Durham County Board of Commissioners. Published by E.M. Uzzell & Co. Courtesy of Documenting the American South, University Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

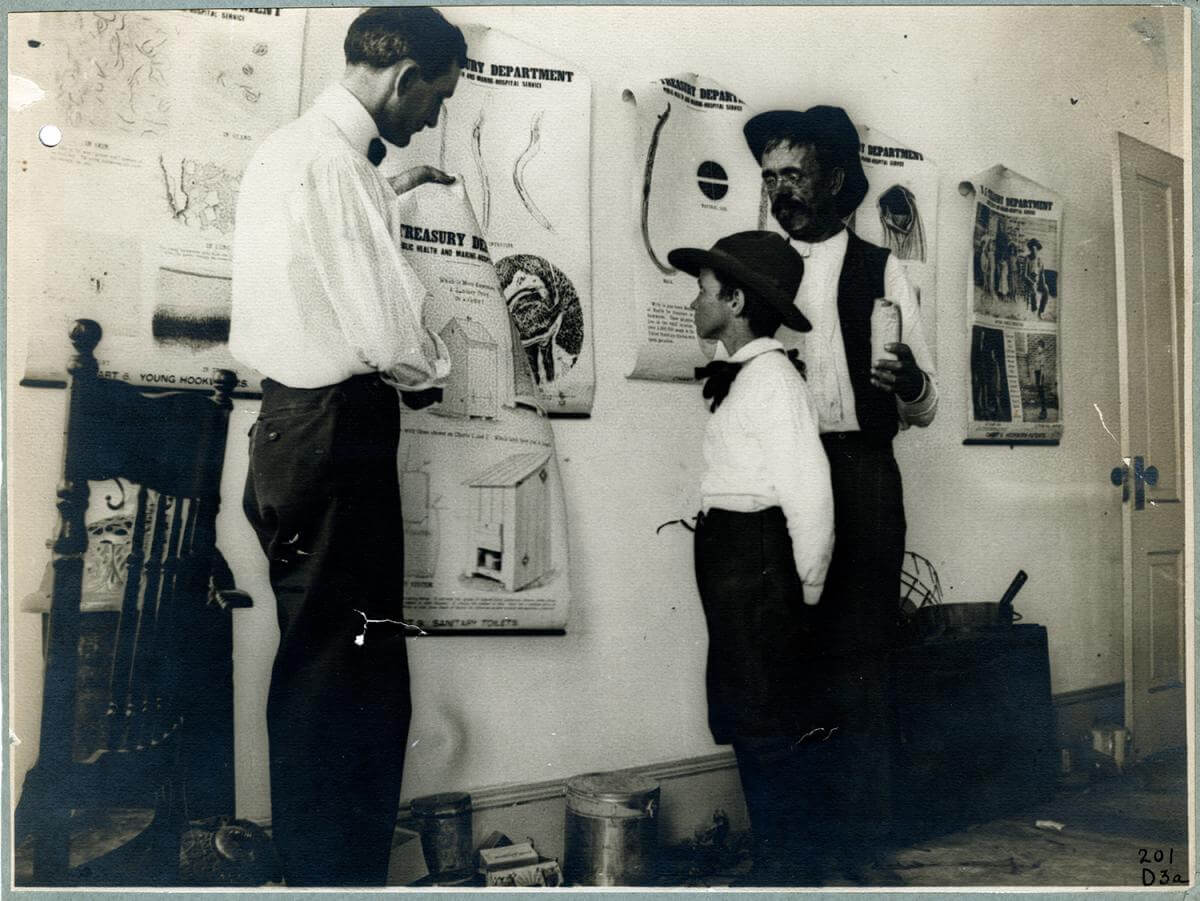

After the discovery of hookworm in Puerto Rico, physicians and their patients began to transform the understanding of peasant malaise. While the ways peasants described their symptoms were not radically different from those of the preceding generation, their understanding of the disease and their efforts to combat it dramatically changed. For one, under US rule, anemics seeking treatment became hookworm patients. If Ashford and the many doctors who joined his crusade were central in introducing these new ideas, so too were the people who ventured for the first time into dispensaries. Campaign officials used reports, pamphlets, posters, brochures, newspapers, and photographs to disseminate medical information, but peasants too spread the word about medical professionals, treatment protocols, and their own pursuit of health. In other words, the new colonial context mediated the emergence of distinct forms of what medical anthropologist João Biehl calls "biomedical citizenship" among peasants mobilizing to demand treatment.18João Biehl, "The Activist State: Global Pharmaceuticals, AIDS, and Citizenship in Brazil," Social Text 22, no. 3 (2004): 105–32. Despite the island's high rate of illiteracy and low rate of schooling, peasants flocked to hookworm stations and municipal offices, requesting access to physicians and medicines. For instance, by 1910 Ashford and Gutiérrez Igaravídez estimated that over 272,000 people had received treatment through the Anemia Commission, and another 30,000 through private physicians. This explosion in popular participation and mobilization of popular expectations in the pursuit of health is one of the most enduring—albeit less recognized—consequences of the campaign. Peasants were more than colonized subjects; they were actors who defined part of the terms under which the campaign developed.

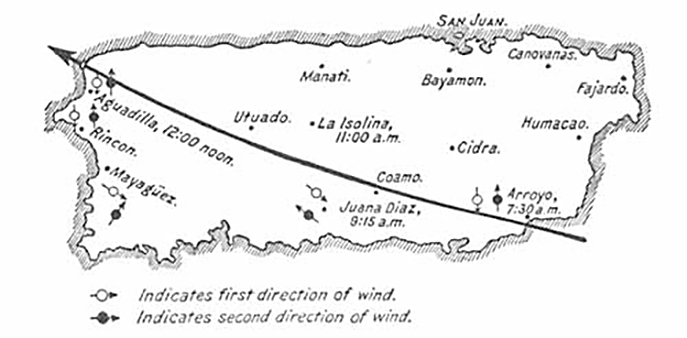

Top, The results of the hurricane, 1899. Originally published in George W. Davis's Military Government of Porto Rico from October 18, 1898, to April 30, 1900 (Washington DC: US Government, 1902), 612. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Hispanic Division, loc.gov/rr/hispanic/1898/sanciriaco.html. Bottom, Path of Hurricane San Ciriaco over the island of Puerto Rico, 1899. Originally published in George W. Davis's Military Government of Porto Rico from October 18, 1898, to April 30, 1900 (Washington DC: US Government, 1902), 612. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Hispanic Division, loc.gov/rr/hispanic/1898/sanciriaco.html.

The origins of this campaign began not in an unpolluted scientific laboratory but amid the devastation left by a terrible hurricane that transformed all aspects of life in the coffee region, and set in motion waves of migrants who sought relief by moving to coastal towns. Some of them would become the first hookworm patients. In time, the development of the campaign in Puerto Rico would provide inspiration for the initial hookworm efforts of the Rockefeller Foundation, a private philanthropic organization founded by John D. Rockefeller in 1913, in the US South and Brazil. But we begin with a poetic rendition of the hopelessness felt after the hurricane.

The Whirlwinds of Health

The verses of the canción "La invasión Yanqui" reveal the deep sense of despair felt by people living in the coffee region after Hurricane San Ciriaco hit the island in August 1899. In a few hours, the coffee crop was swept away and the farms that produced it were reduced to half their value. In the town of Jayuya, whole coffee plantations slipped down the mountains into the river. Over 2,700 deaths were registered and 500 more people disappeared.19On the impact of San Ciriaco, see Stuart Schwartz, "The Hurricane of San Ciriaco: Disaster, Politics, and Society in Puerto Rico, 1899–1901," Hispanic American Historical Review 72, no. 3 (1992): 303–45. Capturing this devastation, the canción conveys the generalized scarcity and destitution the poor suffered:

El café se va a perder (The coffee will spoil)

no queriendo el extranjero; (if the foreigners don't want it;)

entonces, ¿con qué dinero (so with what money)

nos vamos a sostener? (will we support ourselves?)

Después de esta invasión (After this invasion)

vendrán los días peores; (the worst days will come;)

tendremos que ir desfilando. (we'll have to run off.)20Anonymous, "La invasión Yanqui," in La poesía popular en Puerto Rico, edited by María Cadilla (San Juan: Sociedad Histórica de Puerto Rico, 1999), 322.

After critiquing the unwillingness of the United States to provide a secure foreign market for coffee, the narrator asks, "¿A dónde diablos los pobres / tendremos que dir rodando?" (Where the hell will we poor folk go?) In asking this question, the poetic voice—or rather, the voices in the communal register of this composition—portrays the US military intervention as an added catastrophe for the very poor.21On the importance of 1898 in Puerto Rico, see Francisco A. Scarano, "Liberal Pacts and Hierarchies of Rule: Approaching the Imperial Transition in Cuba and Puerto Rico," Hispanic American Historical Review 78, no. 4 (1998): 583–602; Silvia Álvarez Curbelo, Mary Frances Gallart, and Carmen Raffucci, eds., Los arcos de la memoria: El '98 de los pueblos puertorriqueños (San Juan: Postdata, 1998); Fernando Picó, 1898: La guerra después de la guerra (Río Piedras, PR: Ediciones Huracán, 1987); and Lillian Guerra, Popular Expression and National Identity in Puerto Rico: The Struggle for Self, Community, and Nation (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1998).

But hidden in the canción's political commentary was the migration of destitute coffee dwellers from the highlands to the coast to look for aid. Among them, a lucky few found food and shelter in the town of Ponce, where the surgeon general placed Ashford in charge of a large field hospital to care for the "sick poor drifting down."22Bailey K. Ashford, "Report to the Surgeon General," December 22, 1899, Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine, RG 2.3, box 10. Abundant food, however, failed to reduce the high incidence of anemia. Local physicians suggested that these migrants were suffering from malaria, diarrhea, or an obscure fever, but their histories and symptoms did not match those claims. After reviewing a copy of Patrick Manson's Tropical Diseases, Ashford examined the feces of the patients with a microscope, found eggs, and established that an intestinal worm was the cause of the disease.23British physician Patrick Manson (1844–1922) published the first manual of tropical diseases in 1898. While he recognized that the term "tropical disease" defined ailments linked but not exclusively confined to the tropical latitudes, he inaugurated a new medical specialty that associated the tropics with specific diseases. See David Arnold, "'Illusory Riches': Representations of the Tropical World, 1840–1950," Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 21, no. 1 (2000): 6–18. Following Manson's guidelines, he gave them a thymol-derived vermifuge to expel the worms from their bodies. Ashford reported to the US surgeon general that while it was "not probable that those degraded to the level of people whose life is bounded by the tropical plantation, enjoying little beyond cutting cane and picking coffee, [could] have a high standard of personal cleanliness," hookworm was caused by direct contact with soil polluted with human feces "while at work." Ashford, unlike many physicians of the time, not only believed that anemia was caused by hookworm, but recognized that the poor working conditions in plantations sustained the life cycle of the intestinal parasite.

A 'Hammock Case' at the Utuado Station in 1904, Puerto Rico, 1911. Originally published in Bailey K. Ashford and Pedro Guitérrez Igaravidez's Uncinariasis (Hookworm disease) in Porto Rico: a medical and economic problem (Washington DC: US Government Print Office, 1911). Photograph uploaded by Flickr user Internet Archive Book Images. Image is in public domain.

The medication of poor patients was quite rare in turn-of-the-century Puerto Rico. Throughout the nineteenth century, health care was limited to private charities, institutionalized philanthropy, and individual municipalities, and the extent of medical assistance was largely arbitrary. In a 1900 letter to the US civilian governor, Dr. Fawcett Smith, the director of the Superior Board of Health of Puerto Rico, complained that the "sanitary condition" of the island was "primitive, disgraceful, and dangerous to the public." To compound matters, municipal physicians were political appointees who, besides being "scandalously maltreated" and "absurdly" remunerated, were always at risk of losing the favor of the town mayor. The new bureaucracy established by the colonial state did not help, either. According to Smith, the fact that the Superior Board of Health occupied a "subordinate position as a Bureau of the Department of Interior" of the United States led to a "radically defective" administration.24Fawcett Smith to Charles Allen, November 26, 1900, Fondo Fortaleza, Archivo General de Puerto Rico, box 74. Smith's conclusions were as dismal as the failed attempts of US authorities to improve the health of Puerto Ricans. In the following years, despite the imposition of new sanitary measures by the colonial government, diseases continue to increase the mortality rate. After five years of US rule, the average death rate per thousand had increased from 28.9 percent in 1898 to 33.48 percent in 1903.25Bailey K. Ashford and Pedro Gutiérrez Igaravídez, Summary of a Ten Years' Campaign against Hookworm Disease in Porto Rico (Chicago: American Medical Association, 1910), 3.

This dire statistic not only challenged the alleged benevolence of US rule on the island, but also became a source of public embarrassment for supporters of imperialism in the United States. A successful hookworm campaign in Puerto Rico could counter the image of a failing imperial project back in the mainland. Despite the desire of US imperialists to turn the image of Puerto Rico around as soon as possible, attempts to establish the hookworm campaign throughout the island developed gradually and unevenly. In broad terms, the Puerto Rican campaign took place in three distinct phases: an extensive survey in 1903; two subsequent campaigns carried out by the Puerto Rico Anemia Commission in 1904 and 1905; and campaigns under the direction of the Anemia Dispensary Service of the Department of Health, Charities, and Corrections from 1906 to 1909. As institutional structures for hookworm control developed throughout the highlands, the interest in redeeming the jíbaro was both renewed and redefined.

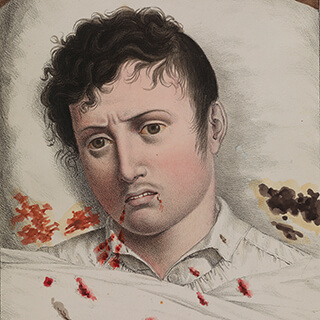

A Typical 'Severe Case', Arecibo, Puerto Rico, 1909, contributed by Dr. Roses Artau. Originally published in Bailey K. Ashford and Pedro Guitérrez Igaravidez's Uncinariasis (Hookworm disease) in Porto Rico: a medical and economic problem (Washington DC: US Government Print Office, 1911). Photograph uploaded by Flickr user Internet Archive Book Images. Image is in public domain.

Convinced that more information was needed to garner the support of the colonial government and medical profession, Ashford and Dr. Walter W. King of the Marine Hospital Service conducted a survey of one hundred cases in Ponce in 1903. While nearly every patient had to overcome the fear of their first medical examination, most of them felt relief after the first treatment. A combination of a thymol-derived vermifuge and salts purged the intestinal worms from patients, relieving patients from anemic exhaustion—the most common symptom of the disease—in about twenty-four to 48 hours. The benefits of taking the medicine must have freed them from their initial apprehension, making the risk associated with the novel treatment worthwhile and easy to promote. In September 1903, Ashford and King published their results in American Medicine. They noted that 30 percent of the deaths charged to "anemia" were caused by hookworm and estimated that the disease affected approximately 90 percent of the rural population.26Bailey K. Ashford and Walter W. King, "A Study of Uncinariasis in Porto Rico," American Medicine 6 (1903): 391–92. In the following issue, the journal editors endorsed a massive eradication campaign on the island. A month later, Governor Hunt promised Ashford that he would take measures to "stop the inroads of this terrible disease." To combat the general skepticism expressed by local physicians, Hunt urged Ashford to publish the principal findings in "the Spanish language" to promote their "circulation over the island" before requesting the doctors' support.27William H. Hunt to Bailey K. Ashford, October 9, 1903, Colección Ashford (hereafter CA), Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Ciencias Médicas, book 1. This approach required the translation and recognition of colonial knowledge about hookworm to win over Puerto Rican physicians.

Portrait of Col. William Crawford Gorgas, ca. 1916. Photograph by Farnham Bishop. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in public domain.

Anxious to gain momentum for the campaign, Ashford also initiated lobbying efforts abroad to rally the support of Puerto Rican physicians. In December 1903, he made public a letter from Colonel William C. Gorgas, now the US chief surgeon of the Department of the East, which endorsed the "vital necessity of combating [hookworm] disease" on the island.28William C. Gorgas to Bailey K. Ashford, December 3, 1903, CA, box 6; Gorgas to Ashford, January 22, 1904, CA, box 6; Ashford to Gorgas, January 28, 1908, CA, box 6. Ashford's work in promoting outside support, especially the validation from the person responsible for the yellow fever eradication in Cuba, proved effective. Later that month, Ashford delivered a speech in Spanish to the members of the Asociación Médica de Puerto Rico (Puerto Rico Medical Association). He framed the eradication campaign as a patriotic duty that would benefit the "whole population." Ashford called on the "well-to-do, refined, educated class" to join the campaign and "lead gently in our sanitary reform.29Bailey K. Ashford, "First Announcement of the Causes of Anemia in Porto Rico to the Medical Profession of the Island," CA, box 1, document 5. His presentation must have been persuasive. Following the event, the Puerto Rican Medical Association committed itself to the crusade against hookworm in order to uplift the "enervated and atrophied spirit of our race."30Manuel Quevedo Baez to Bailey K. Ashford, December 16, 1903, CA, box 5. William P. Craighill, a member of the US Corps of Engineers who was present at the event, was "proud" to witness the command and eloquence that Ashford demonstrated while addressing the "enlightened and progressive members of the medical profession."31William P. Craighill to General O'Reilly, March 14, 1904, Papers of the Office of the Adjutant General, National Archives and Records Administration, RG 97, box 478, document 65329.

Although the medical community in Puerto Rico began to promote the hookworm campaign, not all Puerto Ricans welcomed Ashford's efforts. Sharp political disputes meant that it took longer than expected to dispel the widespread belief that the anemia was caused by hunger. Conservative politicians aligned with pro-Spanish forces claimed that the narrow focus on the disease would distract attention from the terrible malnutrition and devastated economy created by the United States' arrival.32On the pauperization of the Puerto Rican population, see Guerra, Popular Expression, 19–45. "We believe that to deal with this malady neither medicines nor physicians are of value," the editors of the Heraldo Español complained. "Anemia in our country does not mean anything other than hunger."33El heraldo español, June 15, 1904, 1, CA, box 6. Emphasis in the original. See also Bailey K. Ashford, Walter W. King, and Pedro Gutiérrez Igaravídez to Beekman Winthrop, September 23, 1904, CA, box 6. Similar criticism also came from organized labor. Leaders of the Federación Libre de Trabajadores (Free Federation of Workers) claimed that the anemia suffered in Puerto Rico "was occasioned by the lack of sufficient and nourishing food."34See "Puertorican Labor Conditions," CA, box 6, document 175a. During his 1904 visit to Puerto Rico, Samuel Gompers, the president of the American Federation of Labor, blamed greedy employers for the general conditions of poverty, pointing out that the miserable wages did not allow workers to buy enough food.35"Samuel Gompers Aclamado en CA, box 6, documents223a–e.

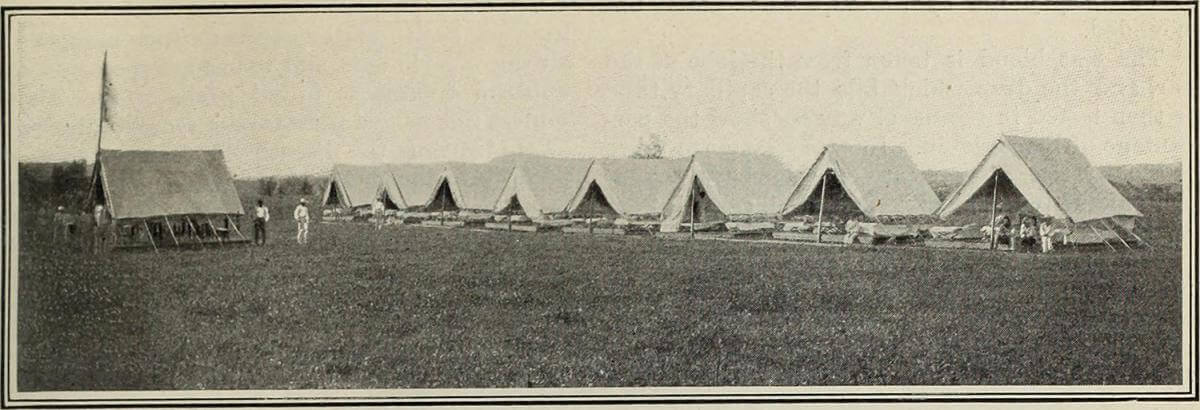

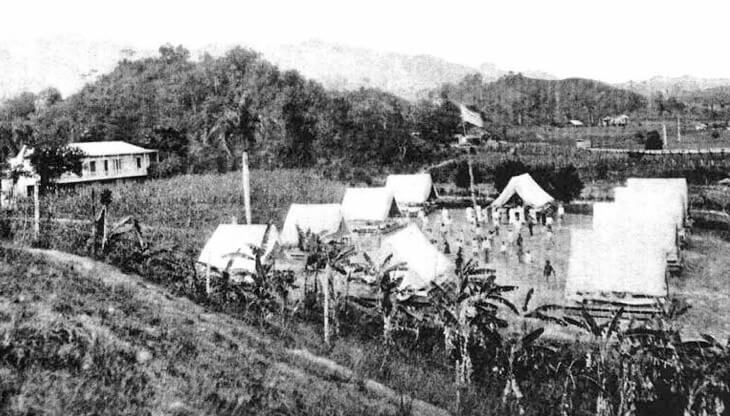

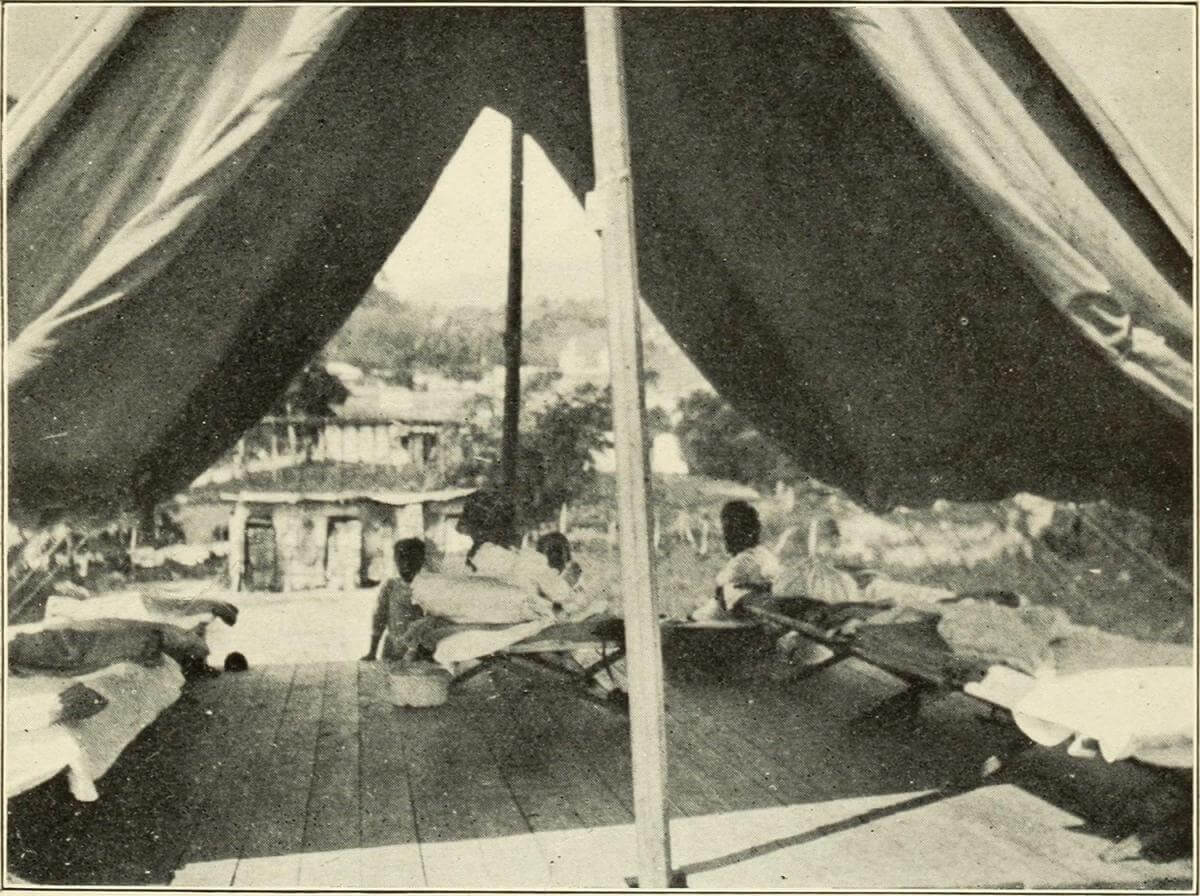

The American camp at Bayamon, Puerto Rico, 1890. Photograph uploaded by Flickr user Internet Archive Book Images. Image is in public domain.

For several years Puerto Rico's newspapers debated the existence of hookworm disease and its treatment, but the intensity of the debate gradually subsided when the colonial government initiated a concerted effort against hookworm. In January 1904, Governor William Hunt asked the legislature of Puerto Rico to allocate $5,000 to "begin an effective campaign" against hookworm disease.36Hunt, Message, 20–21. Within a month, the Puerto Rico Anemia Commission, composed of Drs. Ashford, King, and Gutiérrez Igaravídez, set up a provisional field hospital in Bayamón, a town where Gutiérrez Igaravídez—the only Puerto Rican member of the commission—had secured the support of Dr. Agustín Stahl, one of the most prominent physicians on the island. Stahl offered his services at no cost and allowed the commission to erect the facilities on the grounds of the municipal hospital. The commission reported an "immediate betterment in the patients" after the expulsion of the parasites, and regarded the follow-up treatments of returning patients as proof of the campaign's value. In two weeks, the commission reported, 1,254 patients had been examined and treated, which relieved many doubts among local doctors. "Many physicians," the commissioners observed, "visit the scene of our work and express their conviction that uncinariasis is an extensive epidemic in Puerto Rico."37Bailey K. Ashford, Walter W. King, and Pedro Gutiérrez Igaravídez to Beekman Winthrop, n.d., CA, box 1, document 132. When the Bayamón field hospital closed on April 1904, the San Juan News reported that Ashford was publicly praised for "valuable services and efforts on behalf of the poor sick from anemia." In a farewell ceremony, Stahl "presented the doctor with a distinction, and in a few well-chosen words told him that the 150 signatures attached thereon represented the whole community."38On May 1, 1904, Agustín Stahl held a public ceremony at the Bayamón hospital to commemorate Ashford. See "Dr. Ashford Is Honored," San Juan News, May 3, 1904, 1. After the commission's departure, Stahl continued treating patients until June 15, when the existing medicines ran out.

Field Hospital at Utuado, Puerto Rico, 1911. Originally published in Bailey K. Ashford and Pedro Guitérrez Igaravidez's Uncinariasis (Hookworm disease) in Porto Rico: a medical and economic problem (Washington DC: US Government Print Office, 1911). Image is in public domain.

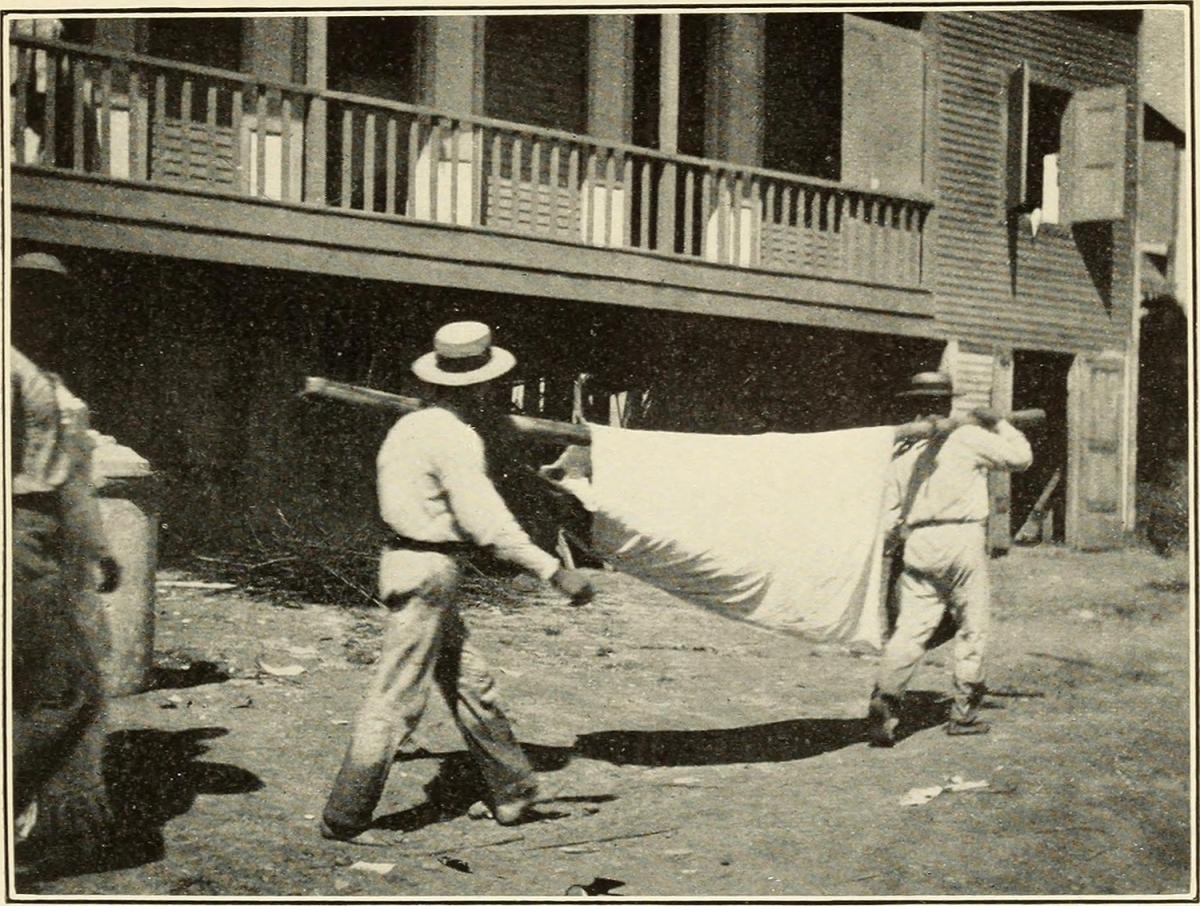

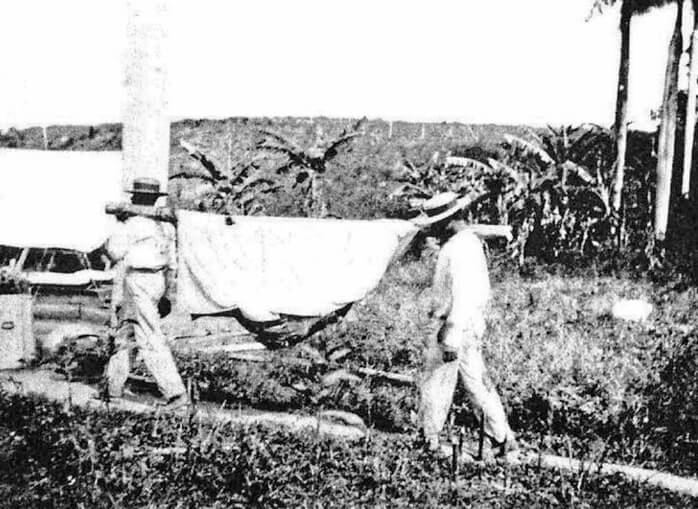

The dispensary camp proceeded to Utuado, a coffee town still suffering from the devastation left by San Ciriaco. After a couple days of delay, the provisional hospital located on high grounds across the Viví River was opened to the public on May 9. The commission believed that with a population of forty thousand, the remote town provided a sufficiently confined environment to study the disease and its treatment. Immediately after the first cases of anemia were treated, a ripple effect drew thousands of men, women, and children to the field dispensary. "Beginning with 10 to 20, by the latter part of July, we were receiving from 125 to 150 new patients daily," Ashford and Gutiérrez Igaravídez reported. "The rate continued to increase, and these, with the old patients returning, made our clinic from 300 to 600 per day."39Ashford and Gutiérrez Igaravídez, Uncinariasis in Porto Rico, 106. As word about the free medical treatment spread, many hookworm patients traveled—some by foot, the severely ill in hammocks—from remote areas to the dispensary.40Bailey K. Ashford, Walter W. King, and Pedro Gutiérrez Igaravídez, Report of the Commission for the Study and Treatment of "Anemia" in Porto Rico (San Juan: Bureau of Printing and Supplies, 1904), 14–15. Those too ill to return to their houses were admitted to the tent hospital.

Top, Interior of Hospital Tent, Puerto Rico, 1911. Originally published in Bailey K. Ashford and Pedro Guitérrez Igaravidez's Uncinariasis (Hookworm disease) in Porto Rico: a medical and economic problem (Washington DC: US Government Print Office, 1911). Photograph uploaded by Flickr user Internet Archive Book Images. Image is in public domain. Bottom, the Activity of the Larva of Nectoramericanus, Puerto Rico, 1911. Originally published in Bailey K. Ashford and Pedro Guitérrez Igaravidez's Uncinariasis (Hookworm disease) in Porto Rico: a medical and economic problem (Washington DC: US Government Print Office, 1911), 159. Photograph uploaded by Flickr user Internet Archive Book Images. Image is in public domain.

Profiting from the experience in Bayamón, patient treatment at Utuado became systematized. Patients arrived early in the morning, some of them after walking for several days on the road, to be examined before noon. After filling out a medical form, they submitted fecal samples for microscopic examination. Once their clinical history was recorded, each patient received a brief lecture on hookworm and an identification card with their case number.41"Comisión de la Anemia de Puerto Rico: Manera de tomar las medicinas," CA, box 5; Bailey K. Ashford, Walter W. King, and Pedro Gutiérrez Igaravídez, Preliminary Report of the Commission for the Suppression of Anemia in Porto Rico (San Juan: Bureau of Printing and Supplies, 1906), 8. They also learned about the use and construction of latrines to prevent the spread of the disease. With much of the money spent, on June 15 the commission ceased to accept new patients, and on August 15 ended the treatment of all patients. In a little over four months, 4,482 patients had been treated in Utuado and its laboratory staff had examined a deluge of over 17,564 fecal specimens.42Ashford, King, and Gutiérrez Igaravídez, Report of the Commission, 93. As they had in Bayamón, the commissioners left a stockpile of medicines with the town doctor before leaving.

Their efforts, however, did not go unnoticed by local residents, the media, or high-ranking officials. The Utuado dispensary was visited by the director of health, charities, and correction; the supervisor of health; Puerto Rican congressional delegates; and Governor Hunt. The pages of La democracia noted that the commission had left a "general current of affection and gratitude" among the people of Utuado. Upon the commission's departure, "a crowd assembled around the kind guests to give them their last goodbye." Within hours, the "spontaneous" farewell had turned into an enthusiastic caravan parading down the town streets. A procession of cars led by various town notables "accompanied [the Anemia Commission] some kilometers outside the town."43"Los verdaderos americanos en Puerto Rico," La democracia, August 31, 1904, 1. Ashford, King, and Gutiérrez Igaravídez later reported that the "former scepticism as to the curability of the disease by medicine" had given way to belief.44Ashford, King, and Gutiérrez Igaravídez, Report of the Commission, 14–15.

The Dispensary Frenzy

In 1905, the commission had an opportunity to develop a more extensive eradication program based on their success in Bayamón and Utuado. Officials quickly learned that the "cured jíbaro" was the "most potent weapon" for convincing skeptics and promoting the campaign.45Bailey K. Ashford to Agustín Stahl, April 18, 1905, CA, box 5. The commission requested continued funding from Governor Beekman Winthrop for this "methodic and scientific organization." It also encouraged the cooperation of "municipalities and their charitable institutions" in transforming a tentative initiative into a centrally coordinated campaign.46Ashford, King, and Gutiérrez Igaravídez, Report of the Commission, 100–101. Governor Winthrop agreed, and the legislature appropriated $15,000 to expand the commission's work. Relative to the magnitude of the enterprise, the sum was quite modest, but it helped transform the experimental and localized initiative into an island-wide campaign focused on the coffee region.47Ashford, King, and Gutiérrez Igaravídez, Preliminary Report, 6.

After several months of repairs and renovations, the commission's headquarters opened on the crest of a hill near the central plaza of Aibonito, a coffee-growing town close to a major thoroughfare. This location facilitated communication with other municipal "substations" opening around the region. Ashford and Gutiérrez Igaravídez served as coordinators in Aibonito, training doctors, evaluating petitions, and corresponding with colonial officials.48Ibid., 8–9. They wrote to plantation owners, encouraging them to construct latrines, instruct their workers about soil pollution, and send hookworm-afflicted individuals to the treatment station. Their pleas, however, did not have the expected results. Plantation owners were rarely willing to incur the added expense of building latrines and, during the picking season, most of them refused to allow workers to visit a treatment station or to walk away from the fields to relieve themselves.49Agustín Stahl, "La uncinariasis y La Liga," Boletín de la Asociación Médica de Puerto Rico 3, no. 4 (1905): 7.

The Entrance to the Dispensary, Aibonito, 1905. Originally published in Bailey K. Ashford and Pedro Guitérrez Igaravidez's Uncinariasis (Hookworm disease) in Porto Rico: a medical and economic problem (Washington DC: US Government Print Office, 1911). Photograph uploaded by Flickr user Internet Archive Book Images. Image is in public domain.

In spite of increased financial resources and hopes of centralization, the commission did not follow a standard procedure as it decided where to extend the campaign. Since the commission responded to individual requests from municipal governments, the establishment of additional dispensaries varied greatly, depending on a town's location, the initiative of its officials, and available resources at the time of the request. The process frequently began with a letter from a town's mayor or municipal doctor to either Ashford or the governor of Puerto Rico. Each town negotiated the extent of the fiscal and administrative responsibilities it would assume, which sometimes determined the outcome of their request. A keen awareness of public health developments in other nations also shaped how some of the petitions were framed. Dr. Martin O. de la Rosa, a physician from the town of Comerio, insisted that "the government of the island, in keeping with the practices of other nations, [was] obligated to finance" a hookworm station in his town.50"Informe del Dr. Martín O. de la Rosa a los Doctores Ashford, King y Gutiérrez, miembros de la 'Puerto Rico Anemia Commission,'" CA, box 4.

As word about the new dispensaries spread from one town to another, the pressure on municipal officials intensified. Municipal doctors did what they could to provide treatment, and hookworm sufferers to demand it, even before many of the petitions for local population stations were submitted to the commission. From January to March 1905, the doctor of the town of San Sebastián improvised a modest treatment facility in his municipality. After over six hundred patients overwhelmed municipal officials with their "requests for medicine," in May the town mayor begged the US governor to provide him with the "necessary medicines to cure our anemics."51Agustín Font to William H. Hunt, May 26, 1905, CA, box 4. The commission awarded San Sebastián medical supplies on the condition that the town doctor travel to Aibonito to receive training at headquarters.52A. H. Frazur to Alcalde de San Sebastián, June 9, 1905, CA, box 4. Similarly, Francisco Sein, the doctor for the town of Lares, organized a rudimentary treatment program after facing increased pressure from peasants. Sein already had experience promoting the control of hookworm. At his own expense, he had published a booklet urging coffee planters, schoolteachers, and neighborhood commissioners to ask people to construct outhouses to "banish the pernicious habit" of soil pollution. He saw the publication as a first step for the "benevolent, worthy, and necessary undertaking" of a "more extensive anti-anemic campaign" in the future.53Francisco Sein, La anemia: Medidas que deben observarse para evitar su propagación (Lares, PR: Tipografía de Bergas, 1905), 3, 7–8. Two months later, the commission supported opening the substation in Lares.54A. H. Frazur to Alcalde de Lares, June 15, 1905, box 4, CA.

Municipal petitions and popular demand thus brought the campaign into remote regions of the coffee highlands. After accepting a town's request, the commission provided medical supplies, laboratory equipment, and, if possible, a field technician. More importantly, it trained the town's doctor to standardize the administration of medicine and to record patient data. The municipality, in turn, provided the service facilities and staff. By the end of the 1905–1906 campaign, ten municipalities had established stations through this process. At four of these stations, the arrangement was for the town to bear all expenses and the physicians to offer their services at no cost as long as the commission furnished the medicines.55The other six towns that provided physicians and facilities were Barros, Coamo, Comerio, Guayama, Moca, and Utuado. List of towns, CA, box 4. The volunteers included prominent physicians such as Agustín Stahl and Enrique Rodríguez González of Bayamón, Isaac González Martínez and Pedro Malaret of Mayagüez, Francisco Sein y Sein of Lares, and Tulio López Gaztambide and Miguel Roses Artau of Arecibo.56Ashford, King, and Gutiérrez Igaravídez, Preliminary Report, 8–9. Through the efforts of Puerto Rican physicians, 18,865 patients had their fecal samples examined, a prescription dispensed, and their medical condition recorded. The commission registered a total of 76,410 visits, including those of patients who returned to the stations for second and third treatments.

Not to be outdone by the efforts of the colonial state, in 1905 the Puerto Rico Medical Association created the Liga de Defensa contra la Anemia (Defense League against Anemia) to complement the work of the commission. The inaugural session was held at the Ateneo Puertorriqueño (Puerto Rican Athenaeum), the meeting place of the island's intellectual elite. The league called on "patriots" of "all classes and social conditions" to recognize the urgent need to fight the disease, hoping that the campaign would turn around Puerto Rico's reputation as an unwholesome and sickly place. One speaker called hookworm a "cruel illness that mercilessly depopulates our fertile landscape."57Mariano Ramirez, José Carbonell, Pedro del Valle, and González Martínez to Bailey K. Ashford, July 19, 1905, CA, box 5. For league members, the solution to this problem was not simply treating hookworm patients, but also curtailing the problem of disposing of human feces. To combat the habit of soil pollution, the league proposed disciplinary measures that included requiring individuals to construct latrines in residences and agricultural fields and fining anyone who polluted the soil.58"Liga de Defensa contra la Anemia," Boletín de la Asociación Médica de Puerto Rico 3, no. 32 (1905): 116–18. On August 6, 1906, league members ratified eight other articles that recommended provisions for the "most complete extirpation" of hookworm disease. Among the most relevant was the compulsory construction of outhouses in every house and provisional latrines for those working in the agricultural fields, as well as the imposition of fines on anyone who defecated on the soil. A month after these measures were ratified, the colonial government approved the proposed sanitary ordinances.59Circular no. 2398, September 25, 1905, CA, box 1.

Medical and civic discourses overlaid each other in the league's crusade. Strict enforcement of the rules of personal hygiene promised to stop disease transmission and cultivate self-discipline among peasants. Reformers appealed to planters by linking hookworm disease to the workers' lack of productivity and the wasted agricultural potential of the land, arguing that hookworm treatment would resurrect the waning coffee economy. The members of the league were motivated not only by a sense of civic duty that marked their professional and moral superiority, but also by the success of the yellow fever campaigns in Havana and in New Orleans. "How we would judge, and how science and the medical world would judge," wrote Agustín Stahl, "if in the last epidemic of yellow fever in New Orleans the doctors had limited themselves to assisting and treating the sick, giving merely secondary attention to exterminating the generating germ of the disease."60Agustín Stahl, "Difusión de la uncinaria y Liga de defensa contra la anemia," Boletín de la Asociación Médica de Puerto Rico 3, no. 5 (1905): 160. In their efforts to expand the hookworm campaign, public health advocates referred to the eradication of yellow fever for their own interests while continuing to develop a transnational ethos of disease eradication that linked the work of physicians from Puerto Rico and the United States.

Top, Utuado (Puerto Rico), coffee processing facility near sugar cane and orange trees, January 25, 1922. Photograph by Robert S. Platt. Center, Puerto Rico, man raking coffee beans on plantation in Utuado, between 1934 and 1969. Photograph by Clarence Woodrow Sorensen and Eugene V. Harris. Bottom, Puerto Rico, boy harvesting coffee beans on plantation in Utuado. Photograph by Clarence Woodrow Sorensen and Eugene V. Harris. Top, center, and bottom photographs courtesy of the American Geographical Society Library, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries.

For most of the campaign, it was assumed that soil pollution was the most significant vehicle of infection. It is hardly possible to assess the short-term impact of the crusade in preventing this practice. The fact that the campaign did not manage significantly to stop the rate of hookworm reinfestation is telling of the difficulty the campaign encountered in changing everyday habits, but it is also telling of the dire economic situation in the coffee region after the hurricane. Growers, seeing their profits rapidly decline, were unwilling or unable to provide latrines for workers. They preferred to invest in replenishing their fields or finding new markets. For most peasants, it was simply impossible to carry out the campaign's directions. They worked all day in fields without service facilities. They could not afford to wear shoes, and much less to construct outhouses. This did not mean, however, that the knowledge that peasants had gained about hookworm was not accepted or widely disseminated. Like that of any other process encouraging people to initiate or change behavior, the reception of the anti-soil pollution message was determined by customary practices, environmental conditions, material limitations, social mimicry, moral enforcement, and repetition.

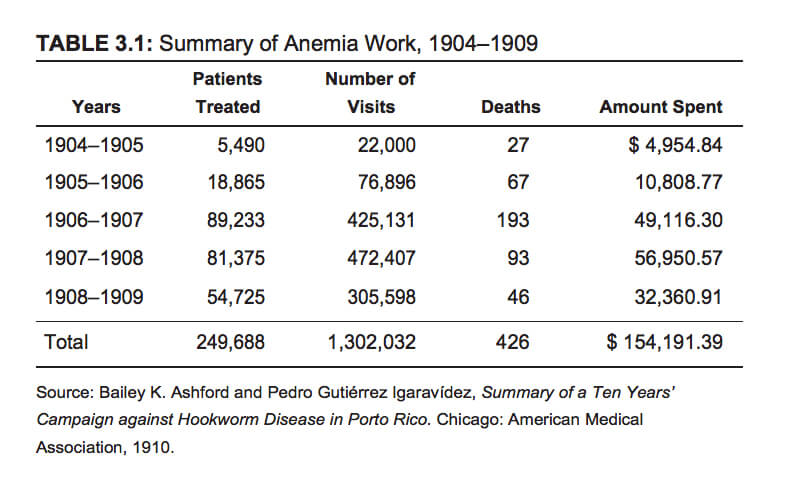

After two years, the commission's work was to become a permanent, island-wide undertaking. In 1906, the legislative assembly passed a law to "create a permanent commission for the suppression of uncinariasis." By "permanent," colonial authorities meant a four-year commission appointed by and under the direct supervision of the governor. At this point, Ashford and King returned to their military service (although both remained honorary members), Gutiérrez Igaravídez became the director of the commission, and Isaac González Martínez of Mayagüez and Francisco Sein of Lares became the other two members. The island was divided in three districts, with one "central" station in the town of Río Piedras and two district stations in the towns of Lares and Mayagüez. Each of these three stations had a similar number of substations under its supervision, but all depended on the central station to collect data and approve budgets. Work began in July 1906 with the opening of six stations. Five towns required stations with hospital service, while six town physicians provided their services free of charge. In the town of Aibonito, the Puerto Rico American Tobacco Company paid the salary of the physician. By the end of the fiscal year, a total of thirty-five stations had examined 89,233 patients and recorded 425,131 visits. During fiscal year 1907–1908, the commission made no essential changes: thirty-five stations remained open and a total of 81,375 patients were treated.

In the following fiscal year, the colonial government made budgetary provisions for continuing the campaign against hookworm. A 1908 law disbanded the commission, and it was replaced by the "Anemia Dispensary Service," a sub-bureau of the Department of Health, Charities, and Corrections, with Gutiérrez Igaravídez retained as its director. During the next two years, the dispensary service increased the number of stations to fifty-five. The campaign had become the first public health service to provide treatment to the majority of the population of the island. In a summary of the ten-year campaign, Ashford and Gutiérrez Igaravídez noted that by November 1910, 272,256 people had received treatment, and they estimated that another 30,000 had been privately treated. In other words, in ten years nearly 30 percent of the population of over one million had been treated for hookworm.61Ashford and Gutiérrez Igaravídez, Summary, 14–15. According to these estimates, 300,000 persons were treated in a population of approximately 1,118,012.

Summary of Anemia Work, 1904–1909, originally published in José Amador's Medicine and Nation Building in the Americas, 1890–1940 (Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 2015). Courtesy of Vanderbilt University Press.

Although the campaign enjoyed success in terms of numbers of patients treated, the results were not exactly what had been intended. The rate of reinfestations remained high because the serious issues of social inequality were not considered. In the 1920s, Ashford regretted the misplaced confidence arising from the systematic purge of the hookworms in patients. He lamented that by concentrating solely on medication, the hookworm crusade "totally lost sight of our enemies' allies, poverty and malnutrition."62Bailey K. Ashford, The War on the Hookworm (New York: Chemical Foundation, 1926), 29. What was lacking in those early years was a will to decrease the levels of isolation and poverty. Medical treatment alone, in short, was incapable of alleviating poverty's most disturbing manifestations: the reappearance of an easily preventable disease.

The Pursuit of Health

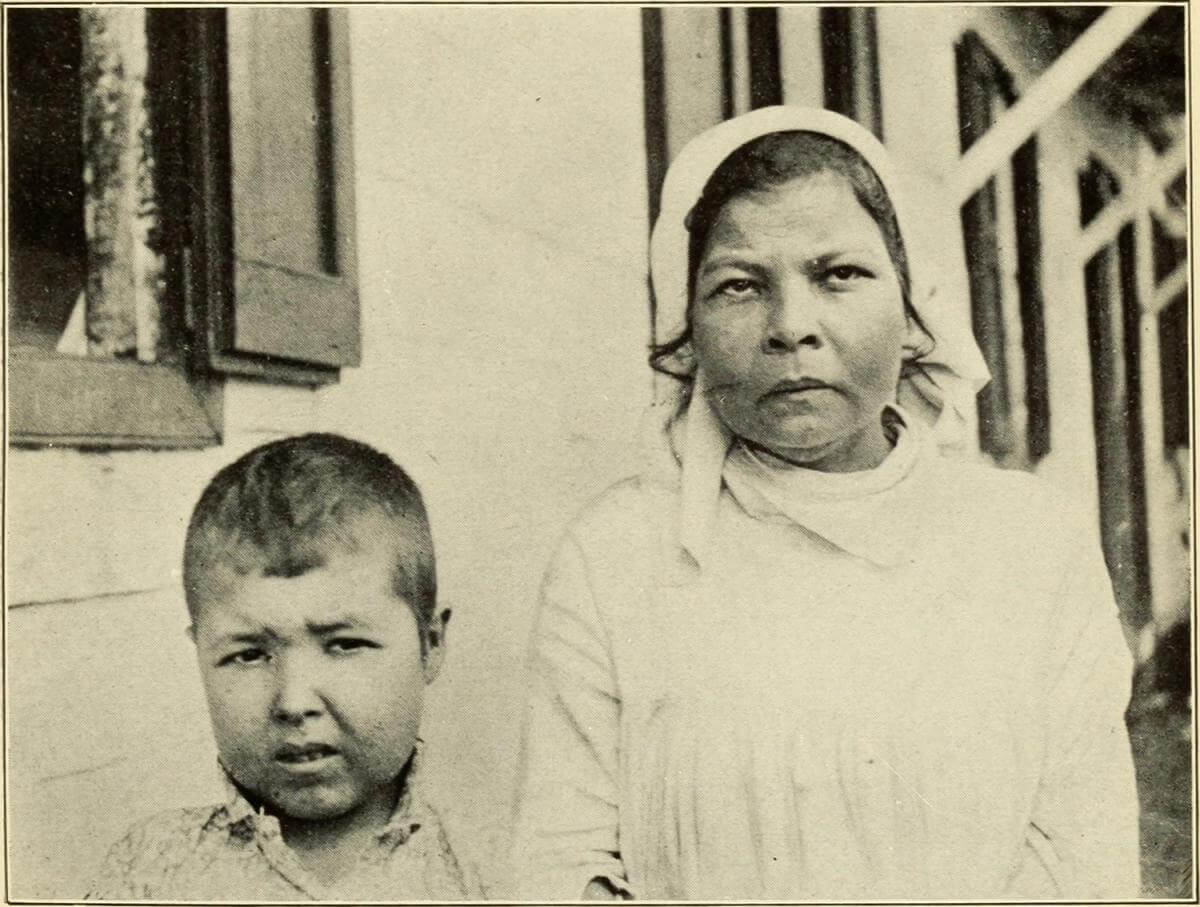

Typical Facial Expression of the Sufferers, Puerto Rico, 1911. Originally published in Bailey K. Ashford and Pedro Guitérrez Igaravidez's Uncinariasis (Hookworm disease) in Porto Rico: a medical and economic problem (Washington DC: US Government Print Office, 1911). Photograph uploaded by Flickr user Internet Archive Book Images. Image is in public domain.

Unlike physicians, politicians, and journalists, who could circulate different opinions about the campaign in the public sphere or print media, the people who visited the dispensaries and took the medicines had few arenas in which to speak. Yet traces of their immensely varied lives persist, however fleetingly and fragmented, in the archival record produced by those in power. Who were those initial patients who overcame the fear of their first medical examination? How do fragmented accounts provide texture and depth to the actions of peasants pursuing hookworm treatment? What meanings did they give to their pursuit of health? The answers to these questions, tentative as they may be, pose several methodological challenges regarding the use of institutional documents to register popular experiences, especially because, although the campaign produced extensive written records, it did not spark any serious struggle that generated judicial case files or trial transcripts. It is possible, however, to partly recover people's experiences, even within the codified structure of institutional sources, by overlapping journalistic accounts, medical records, and photographs, and asking for important details about individual agency.

The case histories of sixty-one "special" patients treated in 1904 in the town of Utuado were preserved in the first Anemia Commission report. As condensed biographies, they provide a limited but invaluable portrait of who these patients were, where they came from, and how they responded to the campaign. Their life stories demand attention because they reveal the realities of a sick and poor population whose voices were often muted in official accounts. These special patients suffered from hookworm disease, but so did many of their parents and siblings. Of the sixty-one cases, twenty-six reported that they had at least one other family member sick with "anemia," and of that number seven had more than three family members who were hookworm sufferers. Twenty-nine cases reported that at least one family member had died of the disease, and in ten of those cases, three or more family members had died of it. Their work opportunities were limited, but they struggled to make ends meet. More than two-thirds of these patients worked on coffee plantations; some of them were women and others were as young as eleven years old. Other patients were cattle herders, tobacco and banana pickers, domestic workers, and washers. Most of these patients lived in the highlands. Many were itinerant workers who moved from plantation to plantation as the coffee matured. Some of them migrated from the coast for the seasonal harvest. They were not homeless, for the most part, but they lived in dilapidated housing. Some patients lived in Utuado, but most had traveled by foot or in hammocks from distant barrios or towns. These patients arrived at the dispensary pale, emaciated, feeble, hopeful, and afraid. All wanted something: to get relief from the disease weakening them.

Method of Bringing in Very Ill Patients with a Hammock Case, Puerto Rico, 1911. Originally published in Bailey K. Ashford and Pedro Guitérrez Igaravidez's Uncinariasis (Hookworm disease) in Porto Rico: a medical and economic problem (Washington DC: US Government Print Office, 1911). Image is in public domain.

It would be a mistake to read these case histories, which are both official and personal in scope, as transparent windows into popular attempts to negotiate public health. Yet they leave little doubt of the broad spectrum of experiences of those taking advantage of the first campaign that made their health a crucial political project. Six case studies illustrate their labor patterns, family histories, and health pursuits. M. G., an emaciated sixteen-year-old, could not work in the fields because of the disease. He reported that three of his family members had died from hookworm. Like many other patients, he had suffered from mazamorra and took iron pills to fight against his anemic state. After three months of treatment, he brought five other family members as patients.63Ashford, King, and Gutiérrez Igaravídez, Report of the Commission, lii. F. M. was a forty-year-old woman who, prior to being hospitalized, had worked as a laundress and a coffee-picker to help support her husband and seven children. After a week, she regained enough strength to walk and to return to her family responsibilities.64 Ibid., xvii. J. C. S., a twelve-year-old coastal migrant, had been treated previously by Ashford in the coastal town of Ponce, where he sold candies as a street vendor. He was re-infested with the parasite when seasonal harvesting brought him to a coffee plantation in the neighborhood of Arenas. After regaining his strength, J. C. S. ran away to seek work elsewhere.65Ibid., xxiii. L. R., a twelve-year-old girl from the distant town of Jayuya, was brought to the dispensary completely emaciated after traveling on a hammock for five days. She died twelve days later in the field hospital.66Ibid., xxxviii. M. T. was a single woman in her twenties who, like her three brothers, came to the clinic weakened by the disease. After her recovery, she was hired as a laundress in the field hospital.67Ibid., xlv. J. M. B., a thirty-year-old field laborer and the father of five, arrived at the dispensary "profoundly convinced that he was sick, but deeply suspicious and prepared for the worst." After a month of treatment, he was sent home, where he resumed his work.68Ibid., lii.

The presence of the commission in Utuado took on a personal immediacy for some of its patients. V. B, a married coffee and banana laborer, "had a small farm on his own until he became too sick to work it. Sold it for a small sum and moved to town to obtain treatment for his sickness." After his recovery, he "proudly boasted that he was able to support his family and no longer begged."69Ibid., xii. V. B. may or may not have seen work as a social responsibility or a symbol of moral worth, but his action does demonstrate that he viewed recovering from his sickness as important enough to sell his belongings and move to town. Once he regained his health, he touted his ability to care for his family. The commission's cases also capture some of the struggles prevalent in the coffee region after devastation of San Ciriaco. One case involved a fourteen-year-old boy whose father, after losing everything in the hurricane, was interned in an insane asylum. Five years later, the boy remained orphaned, barefoot, and sick. "This is one case," noted the report, "in which poor food, hard knocks, and abandonment broke down what might have been originally a strong resistance."70Ibid., xviii.

Typical Face, Boy, Puerto Rico, 1911. Originally published in Bailey K. Ashford and Pedro Guitérrez Igaravidez's Uncinariasis (Hookworm disease) in Porto Rico: a medical and economic problem (Washington DC: US Government Print Office, 1911). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in public domain.

None of these patients' stories are unequivocal, and medical and popular expectations cannot be entirely separated. Yet there is no doubt that most peasants felt better after the treatment, and some even experienced dramatic transformations in their bodies. Myriad scattered sources buttress this point. In one case history after another, the report used phrases such as "good color," "gained much weight," and "improved appearance" to describe the patient's transformation. The commission noted, for example, that a thirteen-year-old coffee picker had "so completely changed as hardly to be recognizable by his friends."71Ibid., xxvi. Similarly, in another case, this time of a seventeen-year-old tobacco picker, it reported that "his facial expression and color has so much changed that his acquaintances did not recognize him on his return home."72Ibid., xxxiii.

Whether by word of mouth or as direct testimony, these stories, like those of the thousands of other patients, must have traveled up and down rivers and trails to family, friends, and neighbors. Peasants in the highlands heard stories that connected the hookworm campaign to family health, household economies, seasonal labor, missing children, sudden deaths, new employment, treatment measures, and physical transformations. Their acts and responses illustrate the multiple ways in which the campaign influenced crucial aspects of daily life. Given that most coffee pickers harbored the parasite for years, their newfound vitality must have transformed their relationship with their bodies and surroundings. These patients incorporated biomedical language in their vocabulary as they recognized the benefits to their own health. As Luis González, the station physician from the town of Humacao, reported to the commission in 1907:

A few days ago a jíbaro presented himself at the station carrying his feces to be examined but the examination was negative, and I said to him: "You have no anemia," to which he replied: "That is a mistake, Doctor; I caught mazamorra the other day, and I must have it." I had to sit down and explain to the patient that he would have to return later, when his mazamorras should have reached his stomach. He did so, and I found the eggs. The country people around here speak very frequently of the necessity of using shoes, of the "microbe" of uncinariasis, of mazamorra in the stomach.73Ashford and Gutiérrez Igaravídez, Uncinariasis in Porto Rico, 219.

González's words cannot be taken entirely at face value, given the report's emphasis on celebrating the campaign. They reveal not only his enthusiasm for the campaign's mission, but also the reach of medical knowledge among peasants who pressured authorities for information and treatment. Moreover, the actions of Puerto Rican physicians and patients in the campaign strengthen the link between public health and the colonial state, regardless of whether or not they actually welcomed the presence of the United States on the island. The physician from the town of Arecibo, for example, celebrated the US presence in the most unabashed terms: "The most beautiful work, the most transcendental and humanitarian that has been effected under the American flag has been, without the slightest doubt, the campaign against uncinariasis."74Ibid., 217. At the very least, the doctor knew that the colonial government wanted to be regarded as generous and paternalistic and that it might be willing to back up this image with concrete help.

The spectacular response to the campaign sprang from those directly benefiting from hookworm dispensaries. Juan Román, one of the patients treated in Utuado, wrote to Ashford in 1904. His two letters are the only correspondence from an ordinary Puerto Rican found in the Colección Ashford (Ashford Collection) at the University of Puerto Rico. The handwriting, spelling, and grammar are unclear, but there is no mistaking his point. Román stated that he would be "eternally thankful" to Ashford and Gutiérrez Igaravídez for their "success" with his illness. Deferential and proud, he wrote, "I want you to see that, although poor I always have gratitude for those who treated me like you have." It was no small matter to write such a letter. The composition itself was a struggle, but the letter also carried the possibility of personal mobility. Before leaving the station, Ashford had promised Román a position in the insular police. Román reminded Ashford of his promise and that he was now able to serve on the force.75 Juan Román to Bailey K. Ashford, September 23, 1904, CA, box 5, document 321. Writing and sending this letter was more than an act of gratitude. It asserted that health without work is not worth much.

Román was not alone in his desire to move on with his life once he recovered. Francisco Viruet, a fourteen-year-old orphan from Utuado, appeared on the doorstep of Ashford's home in San Juan. According to La correspondencia, the boy said to Ashford, "You have cured me, and I have come to your house so you can educate me or place me." Like many others in the coffee zone, the treatment had clearly shaped the boy's future expectations. Having overcome extraordinary physical weakness, he was now ready to continue his education and improve his social standing, given the opportunity. The paper announced that Francisco was interested in finding a "North American or Puerto Rican protector" to educate him. If this was not possible, Francisco was "willing" to be part of the domestic service in any family willing to take him.76"Como aumenta la clientela del doctor Ashford," La correspondencia, August 31, 1904, 1. Francisco understood the position Ashford occupied in society, and sought the doctor's help in pursuing his own uplift after he recuperated.

In Aibonito, Joaquín Sánchez, who had been cured the previous year at the Utuado dispensary, became a town policeman. Eager to contribute to the campaign, he also volunteered as a sanitary inspector. Sánchez "made reports on the construction of latrines, the conditions in the barrios, and assisted very ill patients to reach the hospital."77Ashford, King, and Gutiérrez Igaravídez, Preliminary Report, 8. He even inspected many of Aibonito's more distant neighborhoods and some nearby municipalities. That Sánchez went beyond the line of duty points to one of the most overlooked consequences of the campaign. Like others who benefited from the treatment, Sánchez took an interest in the campaign not out of a desire to civilize or discipline others, but as a person moved by the campaign's core promise of health. Sanchez's experience instilled in him a heightened sense of civic responsibility that, in the face of widespread illness, prompted him to reach out to members of his own community.

Map of Puerto Rico showing distribution of crop lands, 1899. Map by Herbert M. Wilson. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, loc.gov/item/98687184/.

On the ground, however, very few people benefited from the visits of sanitary inspectors. Only in the 1906 campaign was an inspection service formally established, and even then it was limited to the towns of Rio Píedras, Mayagüez, and Lares. During that fiscal year the number of houses visited totaled 5,556 compared to the 89,233 patients treated in stations and the 425,131 total dispensary visits. These numbers demonstrate that, while the campaign was part of an imperial project, neither colonial authorities nor public health officials broke down doors or coerced people into visiting the dispensaries; highland residences were too remote and too dispersed for such actions to be possible. In addition, state presence and infrastructure were nonexistent. Instead, hundreds of thousands of coffee workers walked to the dispensaries in the pursuit of health. Photographic evidence in the town of Utuado shows this much. In some cases, when hookworm stations were not available, the ill marched to the offices of their local physician or town mayor to ask for treatment. The mass experience of receiving a free medical diagnosis, a medicine specific to the disease, and a rapid and effective cure inaugurated a new understanding of the role of people, health care, and the colonial state.

Colonial Circuits