Overview

Karen Pooley reviews Toby L. Parcel and Andrew J. Taylor's The End of Consensus: Diversity, Neighborhoods, and the Politics of Public School Assignments (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2015).

Review

Toby L. Parcel and Andrew J. Taylor's The End of Consensus is a thoroughly researched, multidimensional look at popular support for student assignment policies in the Wake County, North Carolina, Public School System (WCPSS). The district, which educates nearly 150,000 children in 171 schools, is one of the nation's largest. (Private schools only educate about one-tenth of the county's school-aged children.) WCPSS is a rare example of a large school district that is racially and economically diverse and is "alone among large districts across the nation in persisting with a diversity policy as a central feature" (106). Student assignments—either parent-initiated ones (applying to district magnet schools) or district-mandated ones (requiring attendance at a school to balance student populations along racial or economic lines)—form the heart of this policy. The authors, both professors at North Carolina State University, describe the evolution of this policy, noting how dramatic population shifts within the county, increasingly strained school district resources and buildings, and the national politicization of school-related issues appeared to end residents' long-standing support for it. This led to a dramatic school-board shake-up in 2009, when Republican candidates unseated four Democratic incumbents.

Student diversity assignment strategies have been a mainstay in Wake County since 1976, when WCPSS was formed through the merger of a district serving Raleigh and another serving suburban Wake County (14–17). Legislation passed by the North Carolina General Assembly and approved by both school boards made the merger possible. The contentious debates that initially surrounded unification—centering on how to redistribute resources and students in the new district—would ultimately fade as public officials, business leaders, and area residents "generally supported the board's policies" and approved the schools' performance through the 1980s and into 1990s (22). However, as the county's surging population growth in the 1990s and early 2000s increasingly strained district resources, schools' performances declined and political conversations became more polarized. Recurring disagreements reprised those of the 1970s and, writes Parcel and Taylor, "are central to the story of Wake County's dramatic fracturing in 2009" (18). A Republican majority elected to the school board immediately "set to work dismantling and replacing the socioeconomic diversity mandate" behind school reassignments (83).

The End of Consensus explores the rekindling of this public school debate. Parcel and Taylor interviewed current and former members of the school board, business leaders, and local activists, surveyed over seventeen-hundred Wake County residents, and reviewed news accounts and census data to determine the degree to which school board policies, overall school performance, and "ostensibly unrelated" issues such as population growth and the Great Recession "brought about a change in public attitudes on school assignments" and a challenge to the incumbent school board members and the existing consensus (xiv).

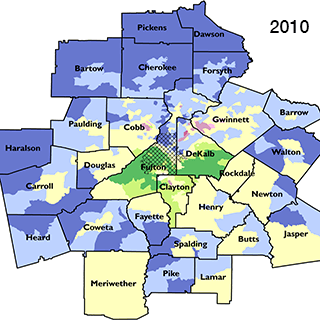

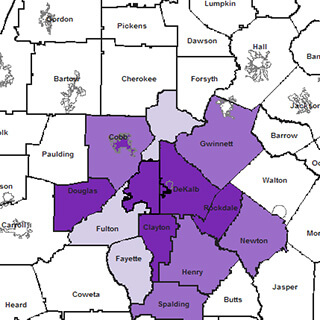

While the district did experience more public discussion around policies designed to keep Wake County schools economically and racially diverse, it remains an open question whether the 2009 election marked the end of widespread support for the district's goal of keeping schools balanced and representative of the district as a whole. This is largely because it is nearly impossible to untangle this apparently growing unease—and the adjustments to student assignment approaches that inflamed the debate—from the dramatic population shifts occurring in Wake County at this time. Between the 1980 Census and the 2009 American Community Survey, the county's population increased from just over 300,000 to nearly 900,000. Three-quarters of this growth occurred between 1990 and 2009. Approximately 275,000 people were added to the county in the 2000s. This "massive influx of people" primarily went into the county's western suburbs, areas that had historically been and had remained largely white. New residents "placed tremendous strains on [school] facilities" (29, 20). This required building new schools at an astonishing rate. Even with 44 elementary schools, fifteen middle schools, and twelve high schools constructed between 1991 and 2010, the board failed to keep pace (51). As land prices rose, so did the cost of each new school.

By the mid-1990s, the district's operating and capital needs exceeded what Wake's county commissioners—"charged by state law to provide schools with much of their funding" (23)—and residents were willing to give. After approving earlier (less costly) bond issuances in 1993 and 1996, Wake residents rejected bond funding for school construction and renovation in 1999 (24). Because the district's physical facilities failed to keep up with the burgeoning student population, more students had to travel further—sometimes ten miles or more (11).

As new schools opened, the school board reassigned students—particularly those living in areas experiencing the most population growth—to maintain the district's racial and economic diversity goals (52). Such reassignments "created a pervasive sense of uncertainty and instability about schooling" and proved "extremely controversial" especially among the county's newest residents, who were least familiar with the district's diversity policy and who would also be called upon to cast ballots for school board members in 2009 (25).

In addition to reassigning students to different schools, the school board also sought to accommodate its growing student body and ensure schools' diversity by increasing its use of year-round schooling (26). This all but mandatory schedule now facing parents in the county's suburbs—again, parents newer to Wake County and less likely than long-term residents to be familiar with a year-round schooling model—was met with "significant resistance": "All these folks had moved here since 1999 [and] did not understand why we had year-round schools" (resident, quoted on page 69). Parents in affected areas did not like the two options the board provided to their children: "to either send their children to a year-round school [closer to home] or have them go to a traditional one, often with an unattractive starting time and long commute" (68). Neither conformed to the model of public education that these parents (typically white, higher-income, and more conservative than those living elsewhere in the county) tended to prefer: neighborhood schools (33, 45).

Frequent reassignments and year-round schooling (results of the diversity commitment) were the policies most at odds with the neighborhood school model and most disliked by Wake County's newest residents (42, 47). As the numbers and voices of newer residents surpassed those of long-time residents, the diversity policy long understood as "fair and beneficial to children of all backgrounds" became "increasingly criticized for undermining performance, forcing long bus rides on children, and limiting parental and community involvement in school" (49).

As the debate shifted to the ballot box in 2009, Parcel and Taylor point out that "the heightened partisanship and polarization that was taking place in national, state, and county politics" coincided with the controversy over Wake's school policies: "Events in Wake County developed as the public's trust in governmental and political institutions across the United States was declining markedly" (80). A significant portion of what appeared to be the faltering consensus on school diversity, then, may instead be more a function of the Great Recession having increased parents' anxieties about their children's education and future rather than a statement on specific actions or policies of the school board (79).

This occurred, too, alongside Wake County's own political revolution (27). The county had consistently backed Democratic gubernatorial and presidential candidates in preceding years, but between the early 1990s and the end of the decade, Wake County was "washed over by a Republican tide that had swept much of the South" (28). By the 2009 elections, "Wake County Republicans were organized, funded, and motivated enough to take on what they perceived as a liberal [school] board and its harmful policies" (31). New associations such as Assignment by Choice (ABC), Take Wake Schools Back, Wake Cares, and Wake Schools Community Alliance formed in the 1990s to resist the school assignment policy (37). In years past, conservative school board candidates had "only tangentially" taken on the district's diversity policy (37). Suburban mayors joined parents in the push to reduce the number of annual reassignments. By 2009 "numerous officeholders in suburban Wake municipalities were involved in a broad lobbying effort to reduce the movement of their residents' children between schools" (54).

Cover of the Independent Weekly vol. 27, no.3, January 20–27, 2010. Featuring Bob Geary's "Rich kid, poor kid: Diversity takes a backseat in Wake schools."

Ultimately, in the 2009 election that is the subject of The End of Consensus, all four of the contested school board seats represented "somewhat conservative-friendly territory" (77). Although, in each case, the incumbents were "associated with the status quo and the Democrats" (77) while the challengers opposed existing school board policies, in each case, too, the larger forces of in-migration (of high-income, white, conservative-leaning individuals), political polarization (on the national stage) and political mobilization were most intense and threatened these incumbents.

At the same time, the school board's new Republican majority was elected by less than 12% of eligible voters, a low turnout (although slightly higher than in prior years) and far from a groundswell of support for a regime change (82). It is not surprising that the new board's efforts to dismantle and replace the district's socioeconomic diversity mandate were quickly rescinded (83, 87). In the 2011 election, residents in the districts that did not vote in 2009 voted out the Republican majority. Partisan disputes continued, but signs of the old consensus returned: voters approved an $810 million construction bond in 2013 (the local Republican Party was one of only a few groups that opposed it, suggesting that its clout in the county had declined) and the new Democratic majority had returned some elements of the district's policy (112).

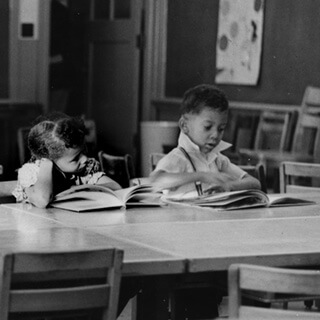

"There is no doubt," write Parcel and Taylor, "that 2009 marked a significant change in Wake County public schools politics" (89, emphasis added). Yet these political changes, in the end, were not accompanied by a comparable change in Wake County public school policies. At its core, The End of Consensus tells of a countywide school district that, as it boomed, had an increasingly hard time presenting itself as a "single community" around which all residents could rally and with which all residents identified (121). Residents instead sought out smaller "communities" in neighborhood-level schools. Such is the inherent challenge of desegregation's heterogeneity: as students and households from an array of racial and economic backgrounds are brought together, fewer may identify with the diverse whole. As Wake County's decades of consensus confirm, this is not an insurmountable challenge, but it highlights the key task of managing perceptions.

Even with its ups and downs, the Wake County Public School System deserves to be lauded for ongoing efforts to provide a diverse population of students with access to quality education and to each other. According to the Common Core of Data released by the US Department of Education's National Center for Education Statistics, only 5% of American public school students get to attend a district such as Wake's: one that is diverse and yet with a below-average portion of students qualifying for free or reduced-price lunch. Instead, roughly three-out-of-five (63%) white public school students attend schools in largely white and low-poverty districts, while a similar share (57%) of minority public school students attend schools in largely non-white and higher-poverty districts. Neither of these districts can prepare students to succeed in a diverse world or provide students with access to opportunity and upward mobility as well as Wake County's economically and racially diverse schools can.

About the Author

Karen Beck Pooley is a senior associate at czb LLC, a neighborhood planning firm, and teaches in the Department of Political Science and the South Side Initiative at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Pooley received a PhD from the University of Pennsylvania's Department of City and Regional Planning in 2007. Her research focuses on neighborhood revitalization strategies, techniques for measuring housing market conditions, and the evolution of federal, state, and local housing policy.

Recommended Resources

Text

Boger, John Charles and Elizabeth Jean Bower. "The Emerging Law of Race and Student Assignment Plans." School Law Bulletin (2011).

Chamberlain, Hope Summerell. History of Wake County North Carolina. Raleigh, NC: Edwards & Broughton, 1922.

Chubb, John E. and Terry M. Moe. Politics, Markets, and America's Schools. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, 1990.

Howell, William G. Besieged: School Boards and the Future of Education Politics. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, 2005.

Peterson, Paul E. The Politics of School Reform: 1870–1940. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1985.

Reese, William J. America's Public Schools: From the Common School to "No Child Left Behind". Updated Edition. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011.

Web

Childress, Sarah. "Report: School Segregation is Back, 60 Years After 'Brown'." Frontline. May 15, 2014. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/report-school-segregation-is-back-60-years-after-brown/.

Cobb, Jelani. "The Failure of Desegregation." The New Yorker. April 16, 2014. http://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/the-failure-of-desegregation.

"Diversity in US Public Schools." Public School Review. http://www.publicschoolreview.com/diversity-rankings/national-data.

Elving, Ron. "Dixie's Long Journey From Democratic Stronghold to Republican Redoubt." NPR. June 25, 2015. http://www.npr.org/sections/itsallpolitics/2015/06/25/417154906/dixies-long-journey-from-democratic-stronghold-to-republican-redoubt.

Jordan, Reed. "America's Public Schools Remain Highly Segregated." Urban Institute. August 27, 2014. http://www.urban.org/urban-wire/americas-public-schools-remain-highly-segregated.

Martin, Michel. "How Important is Economic Diversity in Schools?" NPR. October 18, 2010. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=130647610.

"The Problem We All Live With." This American Life Podcast. July 31, 2015. http://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/562/the-problem-we-all-live-with.

Wake County Open Data Portal. Wake County Public Records. http://data.wake.opendata.arcgis.com/.