Overview

Beth Tarasawa writes about the changing patterns of school segregation for Latino and African American students in Atlanta.

Latinos, the largest minority group in US public schools, are surpassing African Americans as the most segregated racial or ethnic group nationally. This isolation is well documented in states like California, Texas, and Florida with historically high levels of Latino immigration, but less is known about how these newcomers are met in nontraditional destination locales known as the "New Latino Diaspora."1For more about the New Latino Diaspora, see S. Wortham, E.G. Murillo Jr., and E.T. Hamann, Education in the New Latino Diaspora: Policy and the Politics of Identity (Westport, CT: Ablex, 2002). This essay reveals a troubling pattern: for Latinos and African Americans, public high schools in the Metro Atlanta region are experiencing significant racial shifts with greater levels of segregation than integration. These findings have important implications for school administrators, public policy makers, and researchers concerned with the educational opportunities for minority students.

Atlanta Immigration

Prior to the 1980s, Latino and Asian immigrants settled near a handful of geographic centers along the West and East coasts and the Southwest of the United States, but in recent decades immigrants have increasingly gravitated toward other rural and urban areas known as "new settlement" destinations. Potential employment opportunities fueled migration to southern cities as well as attracted a growing number of foreign-born workers. Unlike regions of the country that experienced deindustrialization and unemployment trends over the last thirty years, the Atlanta Metropolitan Region has experienced economic prosperity with its overall population doubling, and the number of jobs more than tripling between 1980 and 2000. The crucial characteristic of Atlanta's economy is its industrial diversity, with no one sector dominating employment.2M.L Owens and M.J. Rich, "Is Strong Incorporation Enough? Black Empowerment and the Fate of Atlanta's Low-Income Blacks" in Racial Politics in American Cities, ed Rufus P. Browning, Dale Rogers Marshall, and David H. Tabb (New York: Longman Publishers, 2003). Atlanta's location in the heart of the US South, its reputation as a business center, and its role as a transportation hub (interstate highways, railroads, and the busiest national airport) also drive economic growth.3A. Hansen, "Black and White and the Other: International Immigration and Change in Metropolitan Atlanta" inBeyond the Gateway: Immigrants in a Changing America, ed. Elzbieta Gozdziak and Susan Martin (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2002).

Economic motivations have influenced domestic migration as well as attracted immigrants. Georgia has the third-fastest-growing foreign-born population rate in the country and the state's Asian and Latino populations more than doubled in the last decade. Occupational opportunities in construction, food processing, and textiles are attracting increasing numbers of immigrants.4R. Giacomini. Statistical abstract of Georgia 2000. By 2000, one in ten Metro Atlanta residents were foreign born. On the county level, some of the most significant increases in Latino growth occurred in Metro Atlanta, including Gwinnett County (up 215%) and Cobb County (up 159%).5US Bureau of the Census 2000.

Changing Faces in Public Schools

Many Metro Atlanta public schools are counting sizeable increases in immigrant students where non-African American minorities were a sparse presence just a decade ago. Recent Latino immigrants who have settled in the South find themselves in a unique situation where racial understanding has long been defined in dichotomous terms of black and white. These newcomers, primarily first-generation Latino students, face educational challenges that are only recently being addressed in public high schools, and because the large Latino growth in Atlanta is so recent, much of the impact of the new wave of immigration is only beginning to make itself felt in the region's schools.6S. Wortham, E.G. Murillo Jr., and E.T. Hamann, Education in the New Latino Diaspora: Policy and the Politics of Identity (Westport, CT: Ablex, 2002).

Public high school enrollments in the twenty-county Metro Atlanta region grew by 109,688 students (an 83.0% increase) from 1994/95-2007/08 (see Graph 1).7Public high schools were examined because they are much more racially and ethnically diverse than elementary or middle schools (Stearns and Lippmann 2003) and offer the greatest potential for interethnic contact. Enrollments in the six largest Metro Atlanta school districts grew by nearly 65,000 students (a 69.9% increase) since 1994/95. However, the suburbs saw their enrollments more than double from just over 39,000 to more than 84,000 (a 114.2% increase) between 1994/95-2007/08.

|

There were clear differences in growth by racial group and by district. As shown in Table 1, between 1994/95-2007/08 the number of white high schoolers in the six largest Metro Atlanta public school districts minimally increased. In the 1994/95 school year, Whites were narrowly the majority (53%) of public high schools in the six major Atlanta- districts. However, by 2007/08 African American enrollment grew by 40,607 high school students so that African Americans now comprise just under 50 percent of total enrollments. Latino high school student enrollment grew by 13,717 raising the Latino proportion to 10%, and the number of other non-white students rose by 4.6 percent consisting of 9% of total enrollments.8Other non-Whites include students identified as Asian and Pacific Islander, Native American and Alaskan Native, or Multi-racial. The continual increase in African American enrollment and the surge in Latino enrollment have led to a non-white majority in the high schools of the six largest Atlanta districts. Although the remaining twenty-one smaller districts also saw significant African American and Latino increases, white growth continued in these areas. Table 2 shows that in the 1994/95 school year, whites were the overwhelming majority (83.6%). By 2007/08, Whites still represent 61.2% of the high school enrollments in the outer suburban districts.

|

|

Patterns of Segregation

Social scientists use multiple measures of segregation trends in education. In the Atlanta Metro region measures of racial isolation reveal changes in district-level racial composition between 1994/95 and 2007/08. Racial isolation is calculated by the number of students in a particular racial group experiencing isolation in schools with more than 50% minority enrollments across school districts.9G. Orfield and N. Gordon, "Schools more separate: Consequences of a decade of resegregation," The Civil Rights Project, Harvard University (Cambridge, MA, 2001). This measure is particularly useful when examining patterns of racial and ethnic isolation over time and helps gauge the level of segregation for multiple minority groups. Schools are first categorized as predominately minority (greater than 50 percent minority) or majority (50 percent or less minority).10G. Orfield and S.E. Eaton, "The Growth of Segregation: African Americans, Latinos, and Unequal Education" inDismantling Desegregation: The Quiet Reversal of Brown v. Board of Education, ed. Gary Orfield and Susan Eaton (New York: The New Press, 1996). The percentage of Latinos and African Americans attending predominately minority institutions within each district is tabulated. For example, researchers calculate the number of Latinos attending schools with more than 50% minority enrollments in district X divided by the total number of Latinos in school district X. This ratio represents the percentage of Latinos attending predominately minority schools in a single school district (X).

In 1994/95, 36 of the 108 Atlanta-region public high schools (33%) were predominately minority—all of which were in Atlanta or nearby suburbs. All Atlanta Public, Decatur City, and DeKalb County public high schools, five of the nine Fulton County public schools, and one Clayton high school were predominately minority. The remaining twenty-two districts continued to be predominately white. By 2007/08, 90 of 152 Atlanta-region schools (59%) were predominately minority. Seventy-four of those schools resided in Atlanta or nearby suburbs. Sixteen high schools that had predominately minority enrollment were located in the outer southern suburbs.

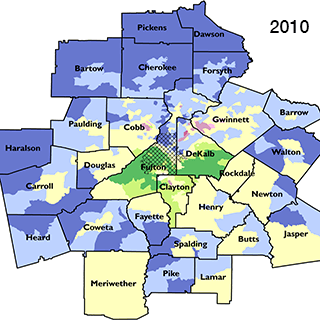

District-level measures of racial isolation also show that the proportion of African Americans and Latinos facing isolation has risen for both groups in the Atlanta Metro region. In 1994/95, 70.1% of African American high schoolers living in the Atlanta Metro region were enrolled in a school that was predominately minority. By 2007/08 81.1% of African Americans attended predominately minority high schools. In contrast, 73.3 % of Latino high schoolers attended predominately white institutions in 1994/95. This trend dramatically shifted and by 2007/08 the number of Latinos enrolled in predominately white high schools dropped to 37.8%. There was also significant variation of racial segregation across the metropolitan region (see Maps 1 and 2).

| Map 1. African American Isolation In Metro-Atlanta: Percentage of African American Students in Predominately Minority High Schools by District | |

| 1994/1995 | 2007/2008 |

| | |

| Map 2. Latino Isolation In Metro-Atlanta: Percentage of Latino Students in Predominately Minority High Schools by District | |

| 1994/1995 | 2007/2008 |

| | |

Segregation and Conflict

While public school enrollments reflect Atlanta's growing diversity, there is a troubling pattern of increased segregation. Measures of isolation suggest most Atlanta public high schools are following similar trends in urban centers nationally, where schools are experiencing significant racial shifts but are becoming more segregated for both Latinos and African Americans. While African American high schoolers are slightly more isolated than Latinos in many Atlanta region school districts, isolation rates have increased for both groups over the past thirteen years. Metro Atlanta public schools are catching up with other cities in frightening ways. By 2007/08 eight out of ten African Americans attended predominately minority high schools in metro-Atlanta compared to seven out of ten in 1994/95. Even more striking, six of every ten Latinos attended predominately minority high schools in metro-Atlanta in 2007/08 compared to three in every ten just thirteen years prior. Observed segregation can be attributed to disparities in racial composition among school districts as opposed to segregation within districts.11C.T. Clotfelter, "Are Whites Still Fleeing? Racial Patterns and Enrollment Shifts in Urban Public Schools, 1987-1996," Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 20.2 (2001):199-221. In 1994/95, this was generally the case in Atlanta where the predominately minority high schools were all located in Atlanta or nearby suburbs with high proportions of African Americans. But by 2007/08, 90 of 152 Atlanta-area high schools were predominately minority. Seventy-four of those schools were situated in Atlanta or nearby suburbs with high levels of racial diversity (both African American and Latino). Additionally, sixteen high schools that had predominately minority enrollment were located in the outer southern suburbs. In line with national research on resegregation, the findings from this essay highlight the recent expansion of segregation to the suburbs.12G. Orfield and N. Gordon, "Schools more separate: Consequences of a decade of resegregation," The Civil Rights Project, Harvard University (Cambridge, MA 2001).

Important questions remain. For instance, the trends discussed here do not get at the tactics of white avoidance of racial and ethnic minorities. Nor can these data distinguish between flight from residential locations or flight into private school alternatives. What factors are associated with Whites choosing to stay in a neighborhood and opt to attend private school? Under which conditions do Whites pack up and move? Further, measures of isolation do not capture actual racial contact within schools. Literature on the tracking of non-White students points to an additional forms of conflict within schools.

As Atlanta's immigrant population continues to increase, research on school segregation remains as important now as it has ever been. Racial conflict, historically understood in terms of black and white in the US South, has expanded to include new contestants in Metro Atlanta public high schools. In an urban region experiencing recent ethnic migration, school demographic patterns continue to reveal contemporary manifestations of conflict.

About the Author

Beth Tarasawa is a PhD candidate in the Department of Sociology at Emory University, where she specializes in the fields of sociology of education and race/ethnic relations. Her research examines the implementation of language assistance programs for English Language Learners (ELL) in metro-Atlanta public high schools.

Similar Publications

| 1. | For more about the New Latino Diaspora, see S. Wortham, E.G. Murillo Jr., and E.T. Hamann, Education in the New Latino Diaspora: Policy and the Politics of Identity (Westport, CT: Ablex, 2002). |

|---|---|

| 2. | M.L Owens and M.J. Rich, "Is Strong Incorporation Enough? Black Empowerment and the Fate of Atlanta's Low-Income Blacks" in Racial Politics in American Cities, ed Rufus P. Browning, Dale Rogers Marshall, and David H. Tabb (New York: Longman Publishers, 2003). |

| 3. | A. Hansen, "Black and White and the Other: International Immigration and Change in Metropolitan Atlanta" inBeyond the Gateway: Immigrants in a Changing America, ed. Elzbieta Gozdziak and Susan Martin (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2002). |

| 4. | R. Giacomini. Statistical abstract of Georgia 2000. |

| 5. | US Bureau of the Census 2000. |

| 6. | S. Wortham, E.G. Murillo Jr., and E.T. Hamann, Education in the New Latino Diaspora: Policy and the Politics of Identity (Westport, CT: Ablex, 2002). |

| 7. | Public high schools were examined because they are much more racially and ethnically diverse than elementary or middle schools (Stearns and Lippmann 2003) and offer the greatest potential for interethnic contact. |

| 8. | Other non-Whites include students identified as Asian and Pacific Islander, Native American and Alaskan Native, or Multi-racial. |

| 9. | G. Orfield and N. Gordon, "Schools more separate: Consequences of a decade of resegregation," The Civil Rights Project, Harvard University (Cambridge, MA, 2001). |

| 10. | G. Orfield and S.E. Eaton, "The Growth of Segregation: African Americans, Latinos, and Unequal Education" inDismantling Desegregation: The Quiet Reversal of Brown v. Board of Education, ed. Gary Orfield and Susan Eaton (New York: The New Press, 1996). |

| 11. | C.T. Clotfelter, "Are Whites Still Fleeing? Racial Patterns and Enrollment Shifts in Urban Public Schools, 1987-1996," Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 20.2 (2001):199-221. |

| 12. | G. Orfield and N. Gordon, "Schools more separate: Consequences of a decade of resegregation," The Civil Rights Project, Harvard University (Cambridge, MA 2001). |