Overview

Ariel Lawrence reviews Dawoud Bey's exhibition, Elegy (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, November 18, 2023–February 25, 2024). Bey is a Chicago-based artist and former MacArthur Fellow known for his large-scale photographs and portraits that explore everyday Black American life. Elegy chronicles the experiences and erasures of enslavement through forty-two photographs and two film installations that encompass the wooded trails of Virginia, plantation cabins in Louisiana, and freedom and fugitivity found on the shores of Lake Erie.

Introduction

One night in the spring of 2006, I found myself on the edges of Richmond, Virginia’s Shockoe Bottom neighborhood with a group of reluctant adolescents from my church youth group, Holga camera in hand. Prone to light leaks thanks to its plastic body, the Holga was a toy camera that allowed me to shift from 35mm to medium format 120mm film. What I liked most about the Holga was its less-than-automatic approach to winding through the frames. With a half turn, one could capture images on top of each other, creating a visual palimpsest of moody, blurred, and imperfect scenes. Walking along the James River, I could see ripples of water over my right shoulder while sounds of cars racing along the highway crept into my left ear.

Our local historian tour guide took us down the river path while detailing the experiences of the enslaved. She spoke about how they emerged from the hull of the ship in complete darkness, after months at sea, disoriented, terrified, and unable to communicate with their captors and, in some cases, with each other. She asked us to close our eyes and imagine what it would be like to stand there, chains rubbing away at our wrists and ankles, as we were dragged along towards an unfathomable fate. The next week I developed the film in the dark room at school. My favorite image, which I submitted to workshop that week, was a shot of my tour guide, looking off into the distance, the nearly barren branches of trees etched uncannily across her face. Her body and the natural world merged into one.

How do you represent the horrific legacy of slavery without the bodies of the enslaved? Historically, abolitionist writers and editors built their political critiques on these vulnerable bodies. This manifested as a hyper-focus on the enslaved body as a site/sight of physical domination under the various machinations of white terror. This representation of Black pain, suffering, and duress proliferated with the spread of photography. From the images of lynched bodies in the post-emancipation era, to the photos of civil rights activists being beaten by police in the 1960s, to our contemporary moment of hyper-surveillance and police brutality, US society can view Black suffering’s ever-mounting evidence.

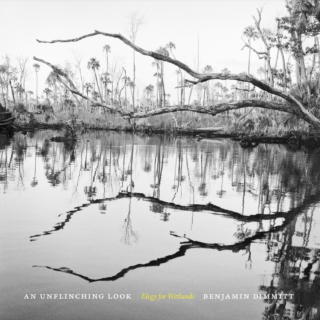

Photographer and visual artist Dawoud Bey explores the history of slavery through landscape photography in his exhibition Elegy which I visited in January 2024 at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Elegy features three photographic collections and two short films that address the legacy of chattel slavery across landscapes in Virginia, Louisiana, and Ohio.

Born in 1953 in Queens, New York, Dawoud Bey, ever drawn to sound, aspired to be a musician before he became a photographer. Bey received his BFA in Photography from Empire State College in 1990, but his career began in New York in the 1970s where he developed a distinct street style featuring predominately Black subjects in everyday life. Influenced by James Van Der Zee and Roy DeCarava, Bey spent much of his career photographing Black faces. Looking through images from collections such as Harlem USA, Class Pictures, or The Birmingham Project, it feels as if you are inundated by the unrelenting gaze of Bey’s subjects staring directly into the camera. Such a dynamic inverts expectations; the subjects are looking at us, into or through us, with as much intention and discernment as we direct towards them.

Compared to his previous work, the large-scale landscape photography featured in Elegy asks viewers to see, and hear, the haunting presence of slavery projected against the landscape without the anchoring presence of Black bodies or Black faces. Bey’s most recent work allows us to recontextualize nature photography by eschewing the innocence of the pastoral scene in order to understand how the bodies of the enslaved, fugitive in their varying trajectories, maintained complicated relationships with nature on American soil. Elegy also contends with the legacies of slavery in the landscape when historical revisionism and erasure has paved over the evidence.

“Stony the Road We Trod” & “350,000”

The first section of Bey’s Elegy, “Stony the Road We Trod,” (a lyric from James Weldon Johnson’s “Lift Every Voice and Sing”), features large-scale gelatin silver prints of the slave trail in Richmond. Tracking the route the enslaved took from Manchester Docks to Shockoe Bottom, Bey examines the landscape along the James River with a botanist’s eye. Each image presents the trail from different perspectives, each shot painted in varying tones of light and shadow that create depth and texture. You imagine the tall stalks of grass prickling your calves, the creeping vines of the foliage wrapping themselves around your ankles, and the overhanging branches grazing the sides of your face; you concede to the invasive nature of the landscape. To see the landscape this closely, one would have to get dirty and bend to the level of the soil. There is no way to keep yourself clean. When the camera pulls back, the fullness of the path feels almost endless. The light peeks through the trees, promising a new twist or turn, but there is a sense that it may never stop.

The first of Bey’s two short films, “350,000,” realizes this interminable momentum by offering the perspective of thousands of enslaved persons who traveled along the trail from the middle passage into bondage. Entirely in black and white, “350,000” is presented as a single extended tracking shot which relies on a haunting soundscape to situate the audience within the sensory experience of bondage. The film begins as it ends: with breath, not calm, but a sharp and sudden gasp, like the sound of a drowning body finally breaking through the line between water and air. This sound echoes Christina Sharpe’s concept of aspiration or “keeping and putting breath back in the Black body” within the “hostile weather” of an anti-Black climate, an act both “violent and life-saving.”1Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 113. The trail is covered in fallen leaves and enshrouded by the endless overhang of trees transitioning from late summer to autumn. Tree limbs refuse to stand upright, but bend inward from left and right, curving into an asymmetrical spiral of light, shadow, and texture. There is some semblance of shade for bodies unseen, but also a sense of being enclosed or entrapped.

As the camera leads viewers down the winding path, there are slow pans to the left and right, from water to thicket, always searching for stability or familiarity in a strange and dangerous landscape. Even with the constant momentum, there are moments of stillness. The sounds of horse hoofs or rattling chains hover. The camera points upward, lingering on the daylight breaking through the shadows of branches and looming patches of grey-white sky. Photographed in a manner often reserved for flashback or dream sequences, the edges of the screen remain soft and blurred. The lack of any discernable body is disorienting, unmooring, echoing the experience of those trapped for months in the hull of a slave ship. Sound is the only anchor: audible labored breathing; guttural exhalations and moans slipping into a rhythmic chanting; the rattling of chains that resemble windchimes.

Bey collaborated with dance and movement scholar E. Gaynell Sherrod to choreograph “350,000”and sound designer Paul Bruski at the In Your Ear Studio in Richmond. The soundscape uses Foley techniques as dancers perform, sometimes barefoot, walking across dirt and gravel while holding large metal chains. While dancers often train to stifle or quiet the sound of their breath, Sherrod makes the labored breath of the dancers more audible, in the absence of their physical form.2Dawoud Bey, Gaynell Sherrod, and Imani Uzuri, “Soundings: Collaborations with Dawoud Bey” (Conversation/Panel, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA, February 9, 2024). Dancers’ bodies disappear and reform through sound, pulling viewers along slowly and reluctantly through the terrain.

“In This Here Place” & “Evergreen”

Elegy returns to the photographic on the remains of defunct plantations in Louisiana. “In This Here Place” presents a collection of images from the Evergreen, Oak Alley, and Whitney Plantations along the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, capturing the slave quarters, some still intact and others commandeered by trees and wild shrubs. These antiquated cabins seem familiar. Looking at Bey’s 2019 “Overgrowth and Fence,” the barely visible cabin swallowed by the bare branches of invasive trees and tall weeds, I am reminded of many neglected houses, once owned in predominately Black neighborhoods in the Deep South, now abandoned on the outskirts of towns.

Many of the images have a spectral quality: each cabin houses the absent-presence of the enslaved. In “Cabin and Benches” the structure is surrounded by long, wooden, unoccupied benches, each shaded by large trees outside the frame. On one side, a rickety wooden shutter is swung open, revealing a small rectangular window blocked by a white curtain pulled back ever so slightly to reveal a tall, thin, black rhombus of darkness. I was convinced that at any point, bodies might emerge from the grey foreground mist, walk towards me, and sit down for some well-deserved rest. In “Cabin and Palm Trees,” the side of the cabin is almost completely obscured by varying leaves of the palm trees—some broad and flat, others a starburst of dense spikes. The window, this time unveiled from the domestic softness of the white curtain, reveals a tall black square, a void from which it felt like someone, shrouded in darkness, could be looking directly at me.

“In This Here Place” takes its name from Baby Suggs’ sermon in the clearing of Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved. Baby Suggs implores Black children to become and be seen, Black mothers to laugh, and Black fathers to dance for their children and their wives. She reminds the members of her community, many who sought their freedom by way of fugitive paths, to love themselves, fully and deeply, precisely because of the white world outside the safety of the woods. “[They] ain’t in love with your mouth,” Baby Suggs announces to the crowd, “they will see it broken and break it again. What you say out of it they will not heed. What you scream from it they do not hear.”3Toni Morrison, Beloved (New York: Vintage Books, 1987), 82. Apt then that “Evergreen,” the second of Bey’s short films featured in Elegy, presents a scream that cannot be ignored.

While “350,000” guides viewers to a single, unbroken shot on one screen, “Evergreen” is a colorful triptych that inundates with multiple shifting visual perspectives. On one screen, the camera hovers over the tops of the trees, moving slowly, as if floating, revealing the rust-tinted tin rooftops of the cabins of the enslaved. Another screen drops to ground level, cutting back and forth between close ups of the lush green grass and sharp stalks of sugarcane leaves piercing from the dirt towards the sky. On a third screen, the camera slowly pans from left to right, one cabin after another, their exterior walls stained with dark copper strokes of rust and oxidation, each one precarious on crumbling brick pillars. As soon you take in one shot on any screen, it switches. The vast perspective of “Evergreen” is awe-inspiring and, at times, overwhelming. I sat through multiple showings, trying to take in one screen at a time, but left feeling there was more to absorb.

The visual palate of “Evergreen”—red-yellow leaves across the ground, brown-blue-green of moss and mold on trees and cabins, and the bright/dull greens of grass and rusty rainwater pooling on the ground and in metal basins—blurs the pastoral and architectural decay. The soundscape intensifies the experience. Bey worked with vocalist and composer Imani Uzuri to articulate the narrative perspective of “Evergreen” where the camera does not reflect a human experience, but that of the disembodied spirits of the enslaved floating and hovering above and across the land.4Dawoud Bey, Gaynell Sherrod, and Imani Uzuri, “Soundings: Collaborations with Dawoud Bey” (Conversation/Panel, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA, February 9, 2024). Whispered words, familiar to those who grew up in the Black church, emerge from everywhere and nowhere: come by here, somebody’s praying, just like a dream, there is peace in the valley for me. Unmoored sounds of hands clapping or a tambourine beating echo throughout. Suddenly, a single extended utterance bursts forth, bending between a scream and a wistful soprano note quickly shifting back into a wail. In “Evergreen,” sounds and words intertwine, crashing into each other at an abrupt speed which approaches and dodges the legibility of music and voice. Uzuri offers us Black sound, harmonious and cacophonous, that refuses categorization; musicality stretched to the furthest comprehension.

The final shot on the center screen of “Evergreen” is, again, one long tracking shot along the center path of the plantation, this time pulling backwards. Viewing the cabins from this vantage, I was struck by the stark architectural uniformity. Each cabin, equidistant and perfectly mirrored, reminds us that this space, these structures, were not only a landscape of suffering, but a community filled with a legally and culturally vulnerable population. Comparing this shot to images such as “Conjoined Trees and Field” and “Irrigation Ditch,” I notice how Bey deploys center composition to create symmetry and balance that emphasizes a single focal point, usually the subject, in an image. Bey often forces the eyes on a central path, a safe space to visually travel along a hostile territory. Both of these photographs and the last shot in “Evergreen” acknowledge and interrogate the linearity of history. While “350,000” moves viewers forward, assuming some level of literal and conceptual “progress,” we also understand that, for the enslaved, a predatory path unfurled. Pulled backward across the center at "Evergreen," we ask, what force carries us and to what end?

“Night Coming Tenderly, Black”

The title of my review comes from a line in Saidiya Hartman’s Scenes of Subjection where she argues for the “opacity” of “black song” as a phenomenon that “troubles the distinctions between joy and sorrow and toil and leisure."5Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America, Revised and Updated Edition (New York: W.W. Norton, 2022), 54. In this, Hartman eschews the “overdetermined reading of the sounds of slavery”6Hartman, Scenes of Subjection, 30. prescribed by twentieth century Black thinkers such as W. E. B. Du Bois, and directs our ears to the more powerful, and at times less legible, “wild notes” of the enslaved, composed in part by the “screams lodged deep inside” that “confound simple expression . . . of black enjoyment.”7Hartman, Scenes of Subjection, 55.

In the almost 160 years since the legal dissolution of slavery in the United States, photography and film have articulated the overdetermined image and, eventual sound, of slavery within the imagination. In both “350,000” and “Evergreen,” Bey’s exclusion of Black bodies forces viewers into a complicated simulacrum of enslaved embodiment. His films interrupt our culturally sedimented expectations not only of what slavery looks and sounds like, but also how it should be experienced. There are no clear heroes or villains in these films, no sense of a triumphant victory of good over evil, not even a sense of who, if anyone, we are following. However, in the midst of this disorientation, we remain anchored by the density of Black sound; we continue to listen through the cacophony to make sense of the experience, not through historical logic, but through a bodily reaction to what unfolds on the screen.

Coming down from “Evergreen,” I entered the final section of Elegy: “Night Coming Tenderly, Black,” its title taken from the last lines of Langston Hughes' poem, “Dream Variations.” This series of photos explores landscapes near Lake Erie in Ohio and Canada and traces the fugitive experience of enslaved persons who liberated themselves, often in the cover of night, from the bondage in southern states. Paying homage to photographer Roy DeCarava, these low-light prints hone the conflicting experiences of fugitivity, wherein a vast, beautiful, open landscape signals exposure and vulnerability while the claustrophobic cover of tree branches means safety and protection. On my way out, I was struck by the last photograph positioned to the right of the exit: a dim shot of Lake Erie, its grey waves rolling into the horizon.

Within the full context of Elegy, viewers can understand the impact of this scene. The slow march from the Manchester docks, from Virginia through the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama to the plantations of Louisiana, and the perilous journey from the Deep South to the northernmost parts of this country, has prepared us for this sight. If “350,000” began with a painful, sharp gasp, this shot of Lake Erie gestured towards a cathartic exhalation.

Leaving Bey’s exhibit, my mind was abuzz: What ethics, if any, are applicable to the ways that we consume the visual lexicon of slavery? Can the cacophony of Black sound that Bey so intricately deployed bring audiences to understand not only Black pain, but Black humanity? Mostly importantly, returning to the image Lake Erie, can any one photograph, detached from its critical context, represent the history of slavery so often erased and buried? When looking at non-descript images of a nature trail or even sugarcane stalks, do we need to hear the density of Black sound to understand what we are looking at? Elegy is, across all five sections of the exhibit, a fully immersive sensory experience which asks audiences to find in the American landscape a history that time and “progress” has obfuscated. As I exited, I could not shake the thought that, to an untrained or inexperienced eye, the difference between the waves of the James River and the waves of Lake Erie—let alone the currents of the Atlantic as seen from the hull of a slave ship—might be difficult to discern. In which direction does the water flow towards freedom?

About the Author

Ariel Lawrence is a PhD candidate in the English Department at Emory University. Her research focuses on Black women-authored lifewriting across multiple genres, and the articulation of ethical reading practices in and beyond the page.

Recommended Resources

Text

Hartman, Saidiya. Scenes of Subjection. New York: W.W. Norton, 1997.

Hartman, Saidiya. "Venus in Two Acts." Small Axe 26 (2008): 1–14.

Sharpe, Christina. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

Wanzo, Rebecca. The Suffering Will Not Be Televised: African American Women and Sentimental Political Storytelling. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2009.

Web

Charlton, Lauretta. "Dawoud Bey, Chronicler of Black American Life." T: The New York Times Style Magazine, October 19, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/10/19/t-magazine/dawoud-bey.html.

Greene Jr., Barry. "Shockoe Project to Encompass Richmond's 'Full History'." VPM, February 28, 2024. https://www.vpm.org/2024-02-28/shockoe-project-to-encompass-richmonds-full-history.

Mitter, Siddhartha. "Dawoud Bey, Full Frame: On Richmond’s Trail of the Enslaved." New York Times, November 9, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/09/arts/design/dawoud-bey-slave-trail-richmond.html.

Sehgal, Parul. "The First Photos of Enslaved People Raise Many Questions about the Ethics of Viewing." New York Times, October 20, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/29/books/to-make-their-own-way-in-world-zealy-daguerreotypes.html.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 113. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Dawoud Bey, Gaynell Sherrod, and Imani Uzuri, “Soundings: Collaborations with Dawoud Bey” (Conversation/Panel, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA, February 9, 2024). |

| 3. | Toni Morrison, Beloved (New York: Vintage Books, 1987), 82. |

| 4. | Dawoud Bey, Gaynell Sherrod, and Imani Uzuri, “Soundings: Collaborations with Dawoud Bey” (Conversation/Panel, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA, February 9, 2024). |

| 5. | Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America, Revised and Updated Edition (New York: W.W. Norton, 2022), 54. |

| 6. | Hartman, Scenes of Subjection, 30. |

| 7. | Hartman, Scenes of Subjection, 55. |