Overview

Kylie Smith reviews Mab Segrest's Administrations of Lunacy: Racism and the Haunting of American Psychiatry at the Milledgeville Asylum (New York: The New Press, 2020) and Wendy Gonaver's The Peculiar Institution and the Making of Modern Psychiatry, 1840–1880 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019).

Christina Sharpe, scholar of English literature and Black studies, articulates the concept of "the wake" as a way of thinking about the long term impact of slavery upon African American life. In her work on symbolism in African American literature and visual culture, Sharpe argues that the wake symbolizes the "endurance of anti-Blackness . . . the on-going problem of Black exclusion from social, political and cultural belonging; our abjection from the realm of the human."1Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016). More than a metaphor, and sparing no spaces or institutions, the wake exemplifies the ways that white people have constructed African Americans as deviant, criminal, and pathological. As much as any professional group, medical practitioners have contributed to the construction of African Americans as physically, intellectually, and mentally inferior to white people.2Rana A. Hogarth, Medicalizing Blackness: Making Racial Difference in the Atlantic World (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017); Christopher D. E. Willoughby, "Running Away from Drapetomania: Samuel Cartwright, Medicine and Race in the Antebellum South," Journal of Southern History 84, no. 3 (August 2018): 579–614; Sharla Fett, Working Cures: Healing, Health and Power on Southern Slave Plantations (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); Todd Savitt and James Harvey Young, Disease and Distinctiveness in the American South (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1988); Marli F. Weiner with Mazie Hough, Sex, Sickness, and Slavery: Illness in the Antebellum South (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012). These attitudes continue to plague current approaches to health care, so that many African Americans live every day in the wake of racism that shapes their physical and mental health.

Recently historians have begun to consider the role of psychiatry in the making of these disparities, exploring the intersection of racism and mental health in Harlem, Pennsylvania, and Washington, DC.3Dennis Doyle, Psychiatry and Racial Liberalism in Harlem 1936-1968 (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2016); Jay Garcia, Psychology Comes to Harlem: Rethinking the Race Question in Twentieth-Century America (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012); Martin Summers, Madness in the City of Magnificent Intentions: A History of Race and Mental Illness in the Nation's Capital (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019); Martin Summers, "'Suitable Care of the African When Afflicted with Insanity': Race, Madness and Social Order in Comparative Perspective," Bulletin of the History of Medicine 84, no. 1 (2010): 58–91; Matthew Gambino, "'These Strangers within Our Gates': Race, Psychiatry and Mental Illness among Black Americans at St. Elizabeth's Hospital in Washington DC, 1900-1940," History of Psychiatry 19, no. 4 (2008): 387–400; Gabriel N. Mendes, Under the Strain of Color: Harlem's Lafargue Clinic and the Promise of an Antiracist Psychiatry (Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 2015); Anne E. Parsons, From Asylum to Prison: Deinstitutionalization and the Rise of Mass Incarceration after 1945 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018). This scholarship builds on the work of psychiatrist and historian Jonathan Metzl. At the Ionia Asylum in Michigan, Metzl documented the ways that the diagnosis of schizophrenia began to skew disproportionately towards Black men in the wake of the Civil Rights movement. Metzl argues that this was an intentional act occurring at the same time as pharmaceutical advertising which cast the Black man as pathologically aggressive, rather than rightfully angry.4Jonathan M. Metzl, The Protest Psychosis: How Schizophrenia Became a Black Disease (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2010). Besides Peter McCandless's study of insanity in South Carolina,5Peter McCandless, Moonlight, Magnolia and Madness: Insanity in South Carolina from the Colonial Period to the Progressive Era (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996). little scholarship has centered on southern states. Two recent books by Wendy Gonaver and Mab Segrest explore some of this missing history. Gonaver's The Peculiar Institution and the Making of Modern Psychiatry 1840–18806Wendy Gonaver, The Peculiar Institution and the Making of Modern Psychiatry 1840–1880 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018). traces the linked histories of the Eastern Lunatic Asylum and the Central Lunatic Asylum in Virginia in the context of slavery and emancipation. Segrest's Administrations of Lunacy: Racism and the Haunting of American Psychiatry at the Milledgeville Asylum7Mab Segrest, Administrations of Lunacy: Racism and the Haunting of American Psychiatry at the Milledgeville Asylum (New York, The New Press, 2020). deals with the first hundred years of Georgia's Central State Hospital in Milledgeville from its establishment in 1842.8This review uses the words for the mentally ill that are prevalent in the literature at the time which did not differentiate between the developmentally disabled and mentally ill in the same way we do today. Therefore, words like "Lunatic" and "Idiot" appear in both the names of asylums and in medical literature. They used here only in the ways they are used in the original sources. I consider these books together because they deal explicitly with the impact of racial thinking on psychiatric practices and seek to place state hospitals in the broader context of slavery and its consequences. They also present an intriguing comparison in their access and approach to sources. What we can know about the past is always limited by the silences of the archive, requiring the expertise of historians to read between the lines or seek hidden voices elsewhere.9Britt Peterson, "A Virginia mental institution for Black patients, opened after the Civil War, yields a trove of disturbing records," Washington Post, March 29, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/magazine/black-asylum-files-reveal-racism/2021/03/26/ebfb2eda-6d78-11eb-9ead-673168d5b874_story.html. The challenges of the psychiatric archive are well demonstrated by the work in progress related to the Virginia asylums after the Civil War. Both of these books demonstrate the challenges and the potential of reading in and beyond the archives. Gonaver's The Peculiar Institution and the Making of Modern Psychiatry is an intimate and detailed telling of the multiple lives contained within a forty-year history of Virginia's institutions based on a discrete set of sources. Segrest's Administrations of Lunacy is a history of Georgia writ large, a weaving of scattered and disparate sources from official archives to newspaper reportage that demonstrate the pivotal role that the hospital at Milledgeville played in the state's history. Both authors seek to answer larger questions about the relationship between slavery and psychiatry, and the wake created as they trace the impact of racism on the lives of the mentally ill.

Gonaver's book is based on the kind of access to sources that historians dream of. The records from Eastern Lunatic Asylum in Williamsburg, Virginia (still operating as Eastern State Hospital) remained hidden in a storage closet in the patient library of the hospital. Gonaver undertook training as a volunteer to work in the hospital, where she was then given access to the records which she then organized and assembled into a coherent collection now housed at the Library of Virginia. The collection includes correspondence and drafts of reports but also, significantly, personal diaries and journals from both workers and patients—a rare find in the psychiatric archive. Gonaver supplements these materials with records from official state sources as she seeks to demonstrate the complex network of relationships between the asylum and its local antebellum community, and between its second superintendent, Dr. John M. Galt II, and the field of medicine. Gonaver arranges the book both topically and chronologically and in doing so demonstrates the way that debates about slavery, and about Black-white relations, track with the expansion of the asylum.

Established in 1773 as the first public institution for the mentally ill in the US, Virginia's Eastern Lunatic Asylum was initially a small institution that housed three hundred patients when John M. Galt became the superintendent in 1841. Gonaver starts her history of the asylum at this point because Galt took over at a time of reform in the care of the mentally ill and he sought to bring new ideas to the way he ran the institution. These ideas quickly placed Galt at the margins of American psychiatry, largely because of his attitude towards race. Before the Civil War, Eastern Asylum employed free Black and enslaved people as attendants and staff and admitted both Black and white patients. Gonaver explains Galt's approach to having an interracial clientele, in which "no peculiar strictness is observed" in terms of accommodations for Black and white patients.10Gonaver, The Peculiar Institution, 33. In an 1848 report Galt wrote that African Americans would always be a minority of patients anyway, and that he saw no detriment to their intermingling. This attitude reflected the entwined lives of Blacks and whites at that time, especially in settings of health and healing where there were small numbers of Black patients.11Fett, Working Cures. Gonaver warns us not to read Galt's attitude as any kind of emancipatory rhetoric, but as representing the practical reality of running an institution with limited space and funding.12See Summers, Madness in the City of Magnificent Intentions. In his work on St. Elizabeth's Hospital in Washington DC, for example, Martin Summers explains how segregation based on race rather than diagnostic category finally became untenable when the space would no longer hold.

Gonaver's goal is to show that ideas about race and slavery were central to the formation of American psychiatry. The existence of enslaved people as patients or as workers doesn't in itself tell us a great deal about how that process unfolded. To do that, we need to understand more about how psychiatry itself was evolving in the mid-1800s, and here Gonaver unpacks the contradictions in the therapeutic regimen at Eastern Asylum under Galt. The prevalent treatment practice in the more progressive institutions in Europe and the US at the time was known as moral therapy, which stressed the importance of clean air and physical activity for recovery. Drawing on the example of places such as the York Retreat in the UK, American reformers designed institutions set among acres of landscaped gardens and outdoor grounds.13Nancy Tomes, The Art of Asylum-Keeping: Thomas Story Kirkbride and the Origins of American Psychiatry (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984). For paying white patients, moral therapy usually meant walking or light gardening in outdoor spaces, or needlework or carpentry inside. For Black patients, "moral therapy" meant something else entirely, and it is here that we learn the way that mental institutions operated in the wake of slavery. Despite Galt's insistence on 'intermingling,' Gonaver shows that Black patients in Virginia's asylums were effectively separated from white patients through demarcations in labor posing as therapy along lines of race and gender. At Eastern Asylum Black female patients worked in the kitchen and the laundry and Black male patients worked in the fields and farm gardens. This was not work as occupational therapy; it was work as day-long, back-breaking labor without which the institution would not have existed, and the white patients would have gone unfed.

Gonaver describes how Galt used enslaved people to care for Black and white patients, again reflecting patterns of healing relationships that existed on the plantation.14Fett, Working Cures. While Galt did not believe that the African American was equal to the white person in terms of intelligence or emotion, he did defend the work of his Black staff who he felt were just as capable of providing excellent care to patients. This bought him into direct conflict with other psychiatrists, in particular Thomas Kirkbride, a Pennsylvania physician at the vanguard of a movement to reform and modernize the psychiatric institution.15Tomes, The Art of Asylum-Keeping. Kirkbride's large and rambling architectural designs were based on the segregation of patients by gender, race, and diagnostic category. He argued publicly with Galt that it was entirely unsuitable for Black patients to be housed alongside whites, or enslaved people to be used as carers.16Summers, "'Suitable Care of the African When Afflicted with Insanity': Race, Madness and Social Order in Comparative Perspective." Kirkbride's concern was for the reputation of the psychiatric institution. His mission was to sell his new asylum plans to potential buyers (i.e., state governments) concerned with white respectability—the Black patient or attendant was anathema to that idea.

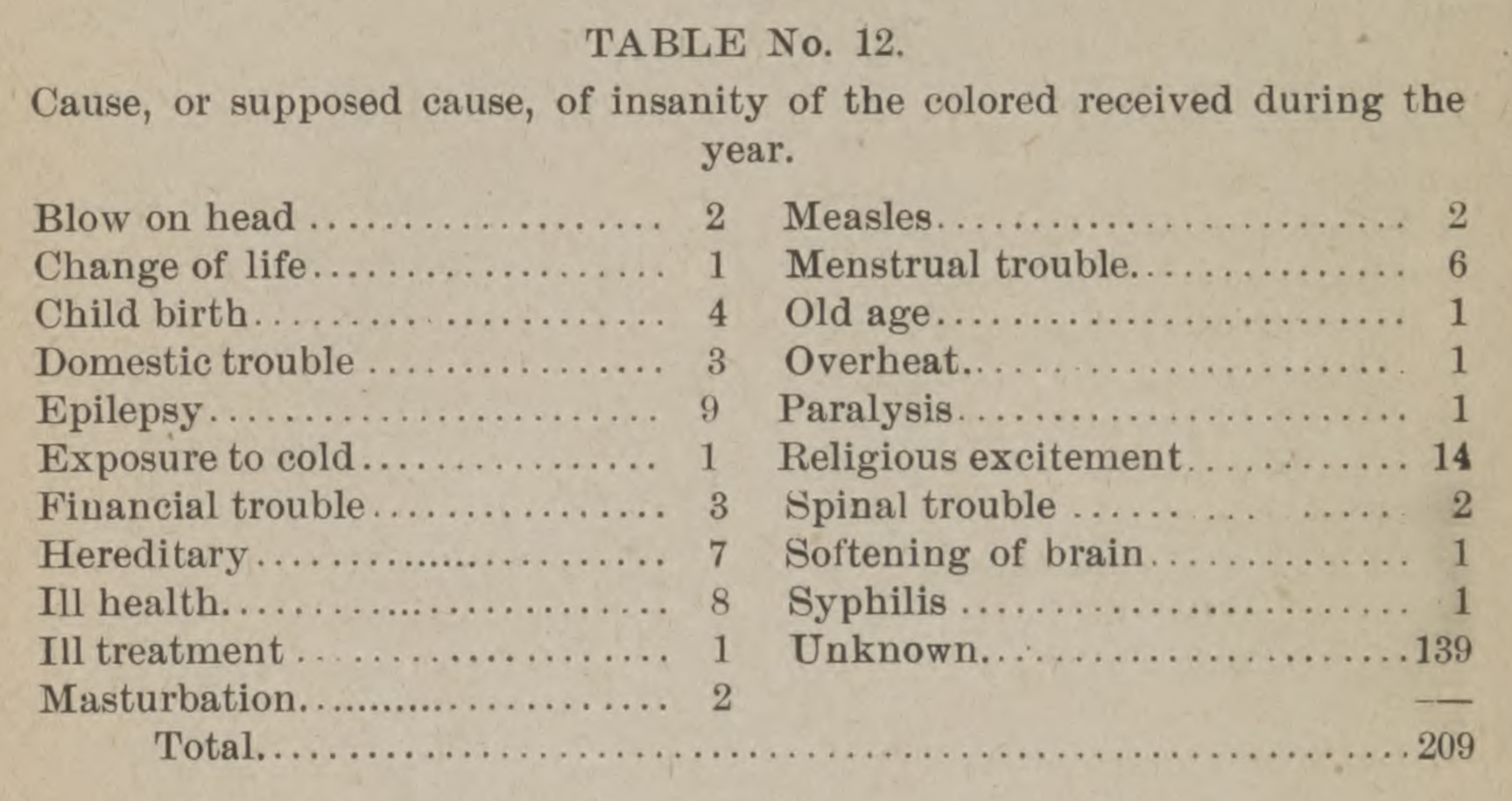

As Galt gave up trying to convince psychiatry's professional bodies of his method's efficacy, Gonaver moves away from an exploration of race relations to include materials that demonstrate intersections with religion and gender. The science of the causes of mental illness in the nineteenth century was hardly precise. Gonaver explores how Galt and his contemporaries were concerned with, as they described it, sensory overstimulation, often taking the forms of excessive religious feeling or female "hysteria." Psychiatry's concern with religious excitement formed part of a large effort to establish scientific knowledge and expertise in place of folk belief (considered superstition), especially in the South in the wake of slavery. This played out in different ways for Black and white patients, and differently again for men and women. As Sharla Fett and other historians have shown, physicians throughout the US were keen to replace traditional healing practices of enslaved Africans as well as the Catholic religiosity of Irish immigrants with what passed for modern scientific rationale.17Fett, Working Cures; Willoughby, "Running Away from Drapetomania;" Deidre Cooper Owens, Medical Bondage: Race, Gender and the Origins of American Gynecology (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2017). Those deemed excessively religious were barely delineated from the mentally ill in the 1800s and they were frequent admittees to Galt's asylum. His approach to women demonstrated the gender bias inherent to psychiatric and medical practices, where genuine problems such as domestic violence, unhappy marriages, and abandonment were too often read as problems of female hormones. Religious excess in women was considered particularly problematic, as it challenged both domestic and public male authority. Gonaver's discussion of gender speaks to the undercurrent of violence in the nineteenth-century South, the burden of which was borne primarily by Black women. She writes: "The asylum expressly denied women's authority in religious matters, paid inordinate attention to female reproductive organs as the cause of insanity, and promoted a racialized vision of healthy womanhood that ignored the trauma of abuse. In so doing, administrators fostered dependency or passivity in white women, and disproportionately characterized black women as recalcitrant imbeciles, laying the foundation for late nineteenth-century medical and political discourse that . . . portrayed black women as naturally promiscuous."18Gonaver, The Peculiar Institution, 113.

The final chapters of The Peculiar Institution and the Making of Modern Psychiatry deal with the impact of the Civil War on Eastern Lunatic Asylum, which was left vulnerable and chaotic when Galt died from suicide via laudanum overdose in 1862. Caught in the mayhem of Confederate and Union struggles over Richmond and Williamsburg, the asylum was ransacked by both sides. The fate of patients and enslaved workers gave way to broader concerns about the status of freed African Americans in postbellum Virginia. This moment coincided with the emergence of a mental health reform movement across the US. Dr. Kirkbride was assisted in his efforts to reform institutional settings by the work of philanthropic campaigner Dorothea Dix, who advocated for state spending for the construction of new asylums. Neither Kirkbride or Dix cared particularly for the African American patient, and it was in this context that Galt's ideas of an interracial institution came to an end. In 1869, the Freedmen's Bureau took over Howard Grove Hospital in Richmond, and the thirty-six African American patients at Eastern Asylum were moved to this facility. In 1870, it became "Central Lunatic Asylum" and was dedicated solely to the care of African Americans. As Gonaver explains, this was the trend across the country, marking the beginning of Jim Crow segregation in health care. The Peculiar Institution and the Making of Modern Psychiatry concludes with a discussion of how psychiatric discourses about Black patients at the end of the nineteenth century centered around false ideas about biological difference and inherent deviance, setting the scene for a century of neglect, underfunding, and abuse.

This idea that the Black patient was somehow less than human is also a central theme in Mab Segrest's Administrations of Lunacy: Racism and the Haunting of American Psychiatry at the Milledgeville Asylum. Segrest uses Sharpe's metaphor of the "wake of slavery" to explore how a place designed to treat the mentally ill inevitably manifested social relations that were shaped and haunted by the violence of slavery. This is a history that runs in blood and sweat down the walls of Milledgeville—which, as the state of Georgia used the asylum as a dumping ground for a multitude of social problems—housed more than 12,000 people by 1960.

When the Georgia State Asylum for Lunatics, Epileptics and Idiots (sometimes referred to as Milledgeville State Hospital) opened in 1842, racial segregation was central to its design and function. Unlike Galt in Virginia, Milledgeville's first superintendent, David Cooper, knew that racial segregation was essential. As Segrest documents in this vast and ambitious book, administrations of lunacy were also expressions of social relations rooted in dispossession, violence, and white supremacy. Segrest demonstrates the way that people are labelled "crazy" is a function of politics and ideology, in which the meaning of the "South" becomes the cause and symptom of the original disease.

Instead of Gonaver's intensive analysis of the institutional archive, Segrest's work is wider-ranging—due to the kinds of sources she has access to and her own interdisciplinary approach. As a historian, Gonaver strives to stay within the bounds of the archive she has uncovered, and contextualizes that archive with other formal archival sources. While she is theoretically informed and definitely interpretive, the style of writing is much more what we would expect from a "traditional" historian. As a literary scholar, Segrest takes a more creative approach. She builds on work she has written elsewhere about Milledgeville's place in the Georgia imagination—a symbol of the gothic and the grotesque.19Mab Segrest, "The Milledgeville Asylum and the Georgia Surreal," Southern Quarterly; Hattiesburg 48, no. 3 (2011): 114–150,158; Segrest, "Exalted on the Ward: 'Mary Roberts,' the Georgia State Sanitarium, and the Psychiatric 'Speciality' of Race," American Quarterly 66, no. 1 (2014): 69–94, https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2014.0000. And she is in some ways forced to be so: the records she uses are limited, extending from the mid-1800s to the early twentieth century, and no longer available to the public. They are not systematic or comprehensive institutional records, but contain important fragments from the hospital that Segrest uses to great effect.

Segrest first sets the scene for the antebellum construction of the Georgia asylum, in the small town of Milledgeville that was the state capital at the time. As we saw with Gonaver's history of Eastern Asylum in Virginia, large estates removed from the hustle and bustle of city life were becoming the preferred place for institution-building in the context of moral therapy which stressed the importance of fresh air and clean living for recovery. Milledgeville State Hospital was built in the context of emerging concerns about the poor, indigent, and "feeble minded" as a threat to society. It also emerged at the intersection with new ideas about the capacity of medicine to "cure" the insane, rather than simply hold them in poorhouses.

Any noble intentions in the establishment of Milledgeville were immediately undercut by the legislature's choice to eschew a Kirkbride-style facility complete with sweeping vistas and sculptured gardens, for the much cheaper single main building which housed all types of patients together, poorly constructed and badly ventilated. And much like Dr. Galt at Eastern Asylum in Virginia, Milledgeville's first superintendent, Dr. Cooper, was his own kind of eccentric. When he sent his first report for publication in the superintendents' association's journal, he made the mistake of telling the truth about his approach to treatment, which was highly aggressive, using all means of restraint at his disposal, and in a style of prose that his northern colleagues found excessive and unprofessional. He earned a severe scolding from the profession's leaders, which saw him removed within his first three years. But, valuable for Segrest, Cooper's report also included extensive case histories. She uses this "opening" to locate the patients he refers to and trace their own histories to tell us something about the lives that brought them to the insane asylum. Her intent is to read "patient narratives through and against the hospital records, newspaper accounts, literary texts, geographical journeys, and oral histories." Her goal is to overlay the history of one hospital with "the dense historical contexts that shaped its patients" and in so doing to write a "restorative history to its Georgia patients, from whose experiences and our own we can continue to understand slavery's afterlives and shape ecologies of sanity in these also turbulent times."20Segrest, Administrations of Lunacy, 10–11.

In order to show connections between the history of the South and the history of psychiatry, and between the past and the present, Segrest divides the book into five parts, from origins of the asylum to "modernity." Each centers around narratives of patients she identified in the records, and whom she traces with diligence through newspapers and census records to place them in their communities and families of origin. This approach serves to humanize the people whose lived experience was shaped by their contact with the Milledgeville Asylum, but it also shows how that asylum itself acted as a tool of social control in the context of white supremacy. The asylum provided substandard conditions for African American patients while it recreated plantation gender roles by putting Black female patients to work in the kitchen and laundry and Black men in the fields. Segrest points out the close relationship between the nearby Georgia Prison Farm. The word "Milledgeville" becomes synonymous with a multitude of ways in which Black bodies can be put to work in what Douglas Blackmon calls "slavery by another name."21Douglas Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York: Anchor Books, 2008).

Segrest locates these practices in the context of psychiatric and medical science that itself descended from the plantation. The turn of the nineteenth into the twentieth century bought scientific obsessions with genetics, heritability, and the problem of the feeble-minded for racial purity. Drawing on writings from racist superintendents such as Doctors Green and Powell, Segrest shows how the attitudes about, and approaches towards, Black patients were "new science, old ideas." It is not simply that Black patients were routinely provided with less rations, less clothing, and inferior buildings, but that these conditions were supported by ideologies of eugenics and mental hygiene, justifying the long term confinement and reproductive sterilization of thousands of people whom the elected politicians of Georgia saw as little more than burdens on the state. Segrest demonstrates the impact of new tools such as the Binet IQ Test and the kind of surveys that put the average Georgian IQ at the bottom of national rankings and led to a rise in admissions and sterilizations numbering in the thousands. In this expansion of psychiatric technologies, the asylum acted as a catch-all for Georgia's disabled who were feared and shunned rather than cared for.

Administrations of Lunacy reaches across disciplines and sources making connections between people and institutions where records are often silent. At times Segrest's approach seems a stretch—she can only guess or hypothesize about motivations or connections that are not made explicit in the records. The book is at its best when Segrest stays grounded in the patient case files she is privy to, bringing to life some of Georgia's most forgotten and marginalized people. Because she is not a traditional historian of psychiatry, she glosses over various internal debates within the profession that shaped its mid-twentieth century approach, especially as a consequence of WWII. Her discussion of links to modernity can feel patched together from other sources, moving far beyond the walls of Milledgeville. But again, this is partly due to the limited records available.

Gonaver's primary source collection ends in 1880, Segrest's in the 1920s. While both authors attempt to make connections between their histories and the present situation in psychiatric and mental health care, neither are experts about the incredibly complex array of forces since the 1960s that have created the current set of disparities for minorities with mental illness.22Kylie M. Smith, "How bigotry created a Black mental health crisis," Washington Post, July 29, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/07/29/how-bigotry-created-black-mental-health-crisis. The community mental health movement of the 1960s led to the closing of massive institutions like the state asylums in Virginia and Georgia. The chronic lack of funding for alternative services has given way to what has been called "trans-institutionalization."23Bernard E. Harcourt, "From the Asylum to the Prison: Rethinking the Incarceration Revolution," Texas Law Review 84 (June 2006): 1751. Attitudes about racial differences continue to plague modern mental health services where Black and minority patients are over-diagnosed with psychotic disorders, underdiagnosed with depressive disorders, and continue to be underrepresented in service utilization data.24M. Alegria, et al., "Disparity in depression treatment among racial and ethnic minority populations in the US", Psychiatric Services, 59 no. 11 (2008): 1264–1272; D. M. Barnes and L.M. Bates, "Do racial patterns in psychological distress shed light on the Black-White depression paradox: A systematic review," Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52 no. 8 (2017): 913–928; J. Breslau, et al., "Racial/ethnic differences in perception of need for mental health treatment in a US national sample," Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52 no. 8 (2017): 929–937. These are national concerns. Many of the problems of Virginia and Georgia's state hospitals were endemic to all large institutions across the US. What Gonaver and Segrest's studies reveal is how the long history and peculiar institutions of Jim Crow segregation ripple through the decades, finding ways to reap themselves on the minds and bodies of Black Americans. Both books are more than partial histories of psychiatry. They are important studies of the ways that institutions such as psychiatric hospitals act as sites through which we can understand broader social relations particular to time and place. They reveal the multiple ways that the wake—the legacy of slavery—continues to shape our national society.

About the Author

Kylie Smith is an associate professor and the Andrew W. Mellon Faculty Fellow for Nursing and the Humanities in the Emory University School of Nursing. She is also associate faculty in the Department of History at Emory University. Her book Jim Crow in the Asylum: Psychiatry and Civil Rights in the American South will be published by the University of North Carolina Press in 2023.

Cover Image Attribution:

Rear view of the Central State Hospital, showing the Building for Chronic Female Patients, Petersburg, Virginia, 1915. Photograph by unknown creator. Originally published in the Forty-Fifth Annual Report of the Central State Hospital of Virginia (Petersburg) for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 1915 (Richmond: Davis Bottom, Superintendent Public Printing, 1915). Courtesy of Internet Archive and University of Chicago.Recommended Resources

Text

Blackmon, Douglas A. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. New York: Anchor Books, 2008.

Fett, Sharla M. Working Cures: Healing, Health and Power on Southern Slave Plantations. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Gambino, Matthew. "'These Strangers within Our Gates': Race, Psychiatry and Mental Illness among Black Americans at St. Elizabeth's Hospital in Washington DC, 1900–1940." History of Psychiatry 19, no. 4 (2008): 387–400.

Harcourt, Bernard E. "From the Asylum to the Prison: Rethinking the Incarceration Revolution." Texas Law Review 84 (2005): 1751–1786.

Hogarth, Rana A. Medicalizing Blackness: Making Racial Difference in the Atlantic World. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

McCandless, Peter. Moonlight, Magnolia and Madness: Insanity in South Carolina from the Colonial Period to the Progressive Era. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Metzl, Jonathan M. The Protest Psychosis: How Schizophrenia Became a Black Disease. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2010.

Parsons, Anne E. From Asylum to Prison: Deinstitutionalization and the Rise of Mass Incarceration after 1945. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Segrest, Mab. "Exalted on the Ward: 'Mary Roberts,' the Georgia State Sanitarium, and the Psychiatric 'Speciality' of Race." American Quarterly 66, no. 1 (2014): 69–94.

Sharpe, Christina. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

Summers, Martin. Madness in the City of Magnificent Intentions: A History of Race and Mental Illness in the Nation's Capital. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Tomes, Nancy. The Art of Asylum-Keeping: Thomas Story Kirkbride and the Origins of American Psychiatry. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984.

Willoughby, Christopher D. E. "Running Away from Drapetomania: Samuel Cartwright, Medicine and Race in the Antebellum South." Journal of Southern History 84, no. 3 (2018): 579–614.

Web

"A Guide to the Records of the Eastern State Hospital, 1770–2009." Library of Virginia, https://ead.lib.virginia.edu/vivaxtf/view?docId=lva/vi03031.xml.

Payne, David H. "Central State Hospital." New Georgia Encyclopedia, Feb. 7, 2006, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/science-medicine/central-state-hospital.

Smith, Kylie M. "How Bigotry Created a Black Mental Health Crisis." Washington Post, July 29, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/07/29/how-bigotry-created-black-mental-health-crisis/.

Smith, Kylie M. Jim Crow in the Asylum: Psychiatry and Civil Rights in the American South. 2021. https://manifold.ecds.emory.edu/projects/jim-crow-in-the-asylum/.

Umeh, Uchenna. "Mental Illness in Black Community, 1700–2019: A Short History." Black Past, March 11, 2019. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/mental-illness-in-black-community-1700-2019-a-short-history/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016). |

|---|---|

| 2. | Rana A. Hogarth, Medicalizing Blackness: Making Racial Difference in the Atlantic World (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017); Christopher D. E. Willoughby, "Running Away from Drapetomania: Samuel Cartwright, Medicine and Race in the Antebellum South," Journal of Southern History 84, no. 3 (August 2018): 579–614; Sharla Fett, Working Cures: Healing, Health and Power on Southern Slave Plantations (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); Todd Savitt and James Harvey Young, Disease and Distinctiveness in the American South (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1988); Marli F. Weiner with Mazie Hough, Sex, Sickness, and Slavery: Illness in the Antebellum South (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012). |

| 3. | Dennis Doyle, Psychiatry and Racial Liberalism in Harlem 1936-1968 (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2016); Jay Garcia, Psychology Comes to Harlem: Rethinking the Race Question in Twentieth-Century America (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012); Martin Summers, Madness in the City of Magnificent Intentions: A History of Race and Mental Illness in the Nation's Capital (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019); Martin Summers, "'Suitable Care of the African When Afflicted with Insanity': Race, Madness and Social Order in Comparative Perspective," Bulletin of the History of Medicine 84, no. 1 (2010): 58–91; Matthew Gambino, "'These Strangers within Our Gates': Race, Psychiatry and Mental Illness among Black Americans at St. Elizabeth's Hospital in Washington DC, 1900-1940," History of Psychiatry 19, no. 4 (2008): 387–400; Gabriel N. Mendes, Under the Strain of Color: Harlem's Lafargue Clinic and the Promise of an Antiracist Psychiatry (Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 2015); Anne E. Parsons, From Asylum to Prison: Deinstitutionalization and the Rise of Mass Incarceration after 1945 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018). |

| 4. | Jonathan M. Metzl, The Protest Psychosis: How Schizophrenia Became a Black Disease (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2010). |

| 5. | Peter McCandless, Moonlight, Magnolia and Madness: Insanity in South Carolina from the Colonial Period to the Progressive Era (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996). |

| 6. | Wendy Gonaver, The Peculiar Institution and the Making of Modern Psychiatry 1840–1880 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018). |

| 7. | Mab Segrest, Administrations of Lunacy: Racism and the Haunting of American Psychiatry at the Milledgeville Asylum (New York, The New Press, 2020). |

| 8. | This review uses the words for the mentally ill that are prevalent in the literature at the time which did not differentiate between the developmentally disabled and mentally ill in the same way we do today. Therefore, words like "Lunatic" and "Idiot" appear in both the names of asylums and in medical literature. They used here only in the ways they are used in the original sources. |

| 9. | Britt Peterson, "A Virginia mental institution for Black patients, opened after the Civil War, yields a trove of disturbing records," Washington Post, March 29, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/magazine/black-asylum-files-reveal-racism/2021/03/26/ebfb2eda-6d78-11eb-9ead-673168d5b874_story.html. The challenges of the psychiatric archive are well demonstrated by the work in progress related to the Virginia asylums after the Civil War. |

| 10. | Gonaver, The Peculiar Institution, 33. |

| 11. | Fett, Working Cures. |

| 12. | See Summers, Madness in the City of Magnificent Intentions. In his work on St. Elizabeth's Hospital in Washington DC, for example, Martin Summers explains how segregation based on race rather than diagnostic category finally became untenable when the space would no longer hold. |

| 13. | Nancy Tomes, The Art of Asylum-Keeping: Thomas Story Kirkbride and the Origins of American Psychiatry (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984). |

| 14. | Fett, Working Cures. |

| 15. | Tomes, The Art of Asylum-Keeping. |

| 16. | Summers, "'Suitable Care of the African When Afflicted with Insanity': Race, Madness and Social Order in Comparative Perspective." |

| 17. | Fett, Working Cures; Willoughby, "Running Away from Drapetomania;" Deidre Cooper Owens, Medical Bondage: Race, Gender and the Origins of American Gynecology (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2017). |

| 18. | Gonaver, The Peculiar Institution, 113. |

| 19. | Mab Segrest, "The Milledgeville Asylum and the Georgia Surreal," Southern Quarterly; Hattiesburg 48, no. 3 (2011): 114–150,158; Segrest, "Exalted on the Ward: 'Mary Roberts,' the Georgia State Sanitarium, and the Psychiatric 'Speciality' of Race," American Quarterly 66, no. 1 (2014): 69–94, https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2014.0000. |

| 20. | Segrest, Administrations of Lunacy, 10–11. |

| 21. | Douglas Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York: Anchor Books, 2008). |

| 22. | Kylie M. Smith, "How bigotry created a Black mental health crisis," Washington Post, July 29, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/07/29/how-bigotry-created-black-mental-health-crisis. |

| 23. | Bernard E. Harcourt, "From the Asylum to the Prison: Rethinking the Incarceration Revolution," Texas Law Review 84 (June 2006): 1751. |

| 24. | M. Alegria, et al., "Disparity in depression treatment among racial and ethnic minority populations in the US", Psychiatric Services, 59 no. 11 (2008): 1264–1272; D. M. Barnes and L.M. Bates, "Do racial patterns in psychological distress shed light on the Black-White depression paradox: A systematic review," Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52 no. 8 (2017): 913–928; J. Breslau, et al., "Racial/ethnic differences in perception of need for mental health treatment in a US national sample," Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52 no. 8 (2017): 929–937. |