Overview

Michele Navakas reviews Cameron B. Strang's Frontiers of Science: Imperialism and Natural Knowledge in the Gulf South Borderlands, 1500–1850 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press and Omohundro Institute, 2018).

Review

Open Cameron B. Strang's Frontiers of Science and you will encounter a fascinating frontispiece that receives no mention in the remarkable study that follows. The image is perhaps too easy for readers to bypass, particularly because modern reproduction obscures some of the details of this image, originally produced as a copperplate engraving in the mid-1770s. Yet it is worth pausing to examine the frontispiece closely because it visually manifests Strang's masterful argument that the local spaces and populations of the Gulf South borderlands—Strang's name for an area that includes today's Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida—were central to early American knowledge production.

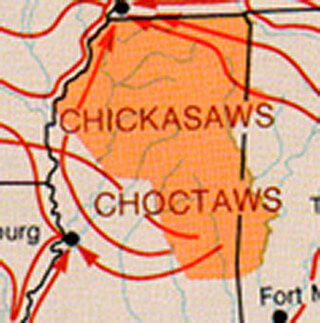

At first glance the image appears to be a familiar allegory of Europe's conquest of the Americas. It centers on an American Indian who kneels before an enthroned Minerva—Roman goddess of wisdom, warfare, arts, trade, strategy, and commerce—and proffers a partially unscrolled map. Scenes of indigenous people offering maps to the colonizer populate the vast literature of European colonization. Referring to this particular image, among other similar ones, Martin Brückner observes that such "ceremonies of submission" are a visual convention that performed dangerous cultural work: they encouraged viewers to imagine the violence of empire as "the voluntary surrender of America by Native Americans."1Martin Brückner, The Geographic Revolution in Early America: Maps, Literacy, and National Identity (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press and Omohundro Institute, 2006), 72–73. Yet close inspection of the frontispiece discloses a different story. This image does not narrate European conquest of the Americas, but rather Anglo-American fascination with a very particular part of North America: the Gulf South borderlands upon which Strang's study focuses—a space variously named and claimed by multiple imperial powers (including Spain, France, Britain and, starting in the 1790s, the United States), numerous Indian nations and confederacies (including the Natchez, Apalachee, Guale, Timucua, Calusa, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Upper Creek, Lower Creek, and Seminole), Africans both free and enslaved, and various groups of pirates and adventurers.

The frontispiece contains a wealth of specific detail about the lands, waters, and variegated populations of these southeastern borderlands. At lower right a smiling cherub uses a compass to inspect a navigational chart that, upon close examination, displays the Gulf of Mexico bordered by a sliver of land marked "Florida." To the lower left of the engraving, a bearded river god sits atop an anchor between two casks pouring forth streams of water. The casks are marked "Mississippi" and "ombech," respectively, signifying the Mississippi River and the Tombechbee River, an antiquated or alternate name for the Tombigbee River, which runs through present-day Mississippi and Alabama.2Arthur S. Marks, "Joining the Past to the Present: William Rush's Emblematic Statuary at Fairmount," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 157, no. 2 (2013): 190. And the American Indian kneeling before Minerva most likely represents one of the particular Indian tribes inhabiting the Gulf South, for this frontispiece was created by Bernard Romans for his 1775 A Concise Natural History of East and West Florida, the first natural history of the Floridas—an area then comprising present-day Florida and parts of Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana—to be published in North America.3For more on this work and its publication, see Kathryn E. Holland Braund, ed., A Concise Natural History of East and West Florida (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999). The Dutch-Anglo-American Romans—like many of the other largely forgotten figures whose stories Strang tells so vividly—turned his local knowledge of the Gulf South to personal and public profit. Romans was a savvy adventurer and polymath who sensed an emerging fervor among the Anglo northeast elite for information about the soil, plants, geography, waters, and people of the southeastern reaches of the continent, and he pays homage to that fervor in his frontispiece. Against Minerva's throne leans a large shield marked "SPQA," likely signifying "Senate and People of the American Republic," rendering the goddess an allegorical figure for Americans in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and other northeastern cities where Romans found financial support for his work among an impressive list of subscribers eager to know of the Gulf South.4Both Marks and Braund suggest that the shield's marking signifies this. For more on the publication and circulation of Romans's work, see Braund, A Concise Natural History.

"Since the nineteenth century," Strang tells us, "historians of the early United States have portrayed spaces beyond the Anglo East (and especially the Northeast) as zones of ignorance with no place in America's intellectual history, much less the history of science" (7). Historians of the Gulf South borderlands in particular found evidence for this portrayal in the writings of early French, Spanish, and Anglo observers who emphasized the "mental incapacity" and "backwardness" of the region's populations, along with the poverty of its lands when compared to more fertile spaces on the continent (7). Yet, for Strang, this familiar story of early American intellectual history began to lose explanatory power when he made a series of archival discoveries that ultimately convinced him that encounters in the southeastern borderlands in fact produced forms and networks of natural knowledge that mattered both within and well beyond the region. The resulting study deftly analyzes a range of neglected or underexamined materials—including letters, journals, military reports, hydrographical charts, geological and boundary surveys, guides to commerce and agriculture, periodical essays, natural histories, and Indian and European maps—that document a thriving intellectual life in the southeastern borderlands and the effects of that life on the meaning, production, circulation, and application of natural knowledge in the empires and nations competing for this space, namely Spain, France, Britain, and (starting in the 1790s) the United States (13–14).

Each of Strang's seven substantial chapters is organized around a set of related case studies of locals who advanced science itself by learning to "navigate and manipulate" a Gulf South "world of rapidly shifting power relations" (5). A brief sampling of these studies affirms that we can no longer think only, or even first, of Anglos living along the Atlantic seaboard when we consider early American knowledge production and circulation (6). For example, we learn of an enslaved native cartographer, a Tawasa man named Lamhatty, whose local geographic knowledge of Florida's Gulf coast enabled his British captors to understand the region when they forced him to produce a map, upon which Lamhatty also chose to document the violence of imperial expansion (53–57). We also learn of a Creek Indian called Yaolaychi, whose mineralogical knowledge of the area around St. Augustine inspired a Spanish expedition in search of precious metals—a quest whose outcome Yaolaychi then shaped by telling vivid stories of a fearsome beast, or "Monster Lizard" (104–110). Turning to the development of astronomy in the Gulf South, Strang introduces Mississippi planter and astronomer William Dunbar, who used the observatory on his Natchez plantation—likely with the help of enslaved people—to produce astronomical knowledge that proved essential to the federal government's mapping of the Mississippi Valley (151–152). And in a chapter on slavery and geology, Frontiers of Science reveals the story of an enslaved shell collector in Alabama who located shells for Philadelphia's Academy of Natural Sciences, where scientists used conchology to understand the age, history, and future of the earth (248).

These and other accounts of Indians, Africans, and Europeans who leveraged local knowledge for different personal ends, and in response to different imperial pressures, call upon us to shift our framework for studying the history of knowledge in early America in several ways. First and foremost, these case studies demand a spatial and demographic shift: like Jane Landers's Atlantic Creoles in the Age of Revolutions, Kathleen DuVal's Independence Lost: Lives on the Edge of the American Revolution, and Alejandra Dubcovsky's Informed Power: Communication in the Early American South, Frontiers of Science affirms that we must look south to fully understand that a range of variegated landscapes and populations have shaped the history of North America at every turn. This spatial and demographic shift necessitates a chronological shift in our history of early American knowledge. For one, we can no longer consider that history solely in relation to the context of British colonialism, for science and empire entwined in the Gulf South for nearly three hundred years prior to US founding and continued to do so long after Britain's thirteen colonies became the first United States.

Finally, and provocatively, Strang's work demands at least two epistemological shifts. First, we must expand our definitions of what counts as "natural knowledge," "science," and "scientific practice." At its broadest level, this book usefully reminds us that science in early North America was not the professionalized disciplined that it would start to become during the late nineteenth century, but rather a capacious practice that engaged a broad and interested public in places far beyond academic or other institutional spaces. In this way, Strang's study joins others that widen the scope of early American knowledge-making, including Susan Scott Parrish's American Curiosity: Cultures of Natural History in the Colonial British Atlantic World, Laura Dassow Walls's Passage to Cosmos: Alexander von Humboldt and the Shaping of America, and Britt Rusert's Fugitive Science: Empiricism and Freedom in Early African American Culture. And Strang productively amplifies the scope of these studies by considering multiple cultures—Indian, African, Anglo, French, and Spanish—across a timespan of more than three centuries (1500–1850).

Second, Frontiers of Science also demands that we recognize the constitutive role of imperial violence in the production of scientific knowledge in North America. For empire occasioned the interactions—many of them forced—among an astonishing array of materials, practices, and practitioners that scientific advancement required. Indian captivity facilitated British cartography (53–57). US expansion sponsored ethnography by making black and Indian bodies available to white "experts" (225). And plantation slavery enabled specimen collection and observation that proved essential to geological research (245). Likewise, the production of scientific knowledge did not always lead to freedom—especially for the producers. For example, whereas Yaolaychi's storytelling increased his status among Spanish officials and impeded their access to local mineral resources (104–116), Lamhatty's mapmaking facilitated British slave trading (61), and many Africans with natural and spiritual expertise risked imprisonment and death for their knowledge (97).

Widely varying effects resulted from the entwining of empire and science in the Gulf South across multiple centuries, yet Strang's skillful illumination of these effects upends any assessment that the continent's borderlands lack "a meaningful history of knowledge" (131). That assessment, Strang recognizes in the epilogue, has present-day effects: it risks producing "a narrow vision of America's cultural past" that can then be used "to justify ongoing exclusion and inequality" (344). A perspective on the Gulf South as somehow backward, separate, and expendable perhaps manifests most publicly these days in environmental disasters that result directly from the uneven distribution of federal resources to the South more broadly. If the humanities are useful for showing us that the past is "still part of the present with implications for the future," as Dominick LaCapra explains, then we need more studies like Frontiers of Science that recover a more inclusive early American history.5Dominick LaCapra, Understanding Others: Peoples, Animals, Pasts (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018), 165.

About the Author

Michele Navakas is an associate professor of English at Miami University of Ohio where she teaches early American literature, culture, and environment. She is the author of Liquid Landscape: Geography and Settlement at the Edge of Early America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018), which won the 2019 Rembert Patrick Award and the 2019 Stetson Kennedy Award from the Florida Historical Society. She is currently at work on a cultural history of coral and politics in early America.

Cover Image Attribution:

The Coast of West Florida and Louisiana, The Peninsula and Gulf of Florida, 1775. Maps by Thomas Jeffreys and Robert Sayer. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division, loc.gov/item/73694449.Recommended Resources

Text

Bleichmar, Daniela. Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Carney, Judith Ann, and Richard Nicholas Rosomsoff. In the Shadow of Slavery: Africa’s Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

DeRosier Jr., Arthur H. William Dunbar: Scientific Pioneer of the Old Southwest. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2007.

Iannini, Christopher P. Fatal Revolutions: Natural History, West Indian Slavery, and the Routes of American Literature. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press and Omohundro Institute, 2012.

Murphy, Kathleen S. "Collecting Slave Traders: James Petiver, Natural History, and the British Slave Trade." William and Mary Quarterly 70, no. 4 (2013): 637–670.

Parrish, Susan Scott. American Curiosity: Cultures of Natural History and the Colonial British Atlantic World. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press and Omohundro Institute, 2006.

Parsons, Christopher M. A Not-So-New World: Empire and Environment in French Colonial North America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018.

Romans, Bernard. A Concise Natural History of East and West Florida. Facsimile reproduction of the 1775 edition, with an introduction by Rembert W. Patrick. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1962.

Rusert, Britt. Fugitive Science: Empiricism and Freedom in Early African American Culture. New York: New York University Press, 2017.

Smith, F. Todd. Louisiana and the Gulf South Frontier, 1500–1821. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2014.

Web

"Early Maps of the American South." University of North Carolina Research Laboratories of Archaeology. Last modified January 1, 2018. http://rla.unc.edu/emas/.

"Environmental Racism." The Sound and the Furious. Podcast. January 25, 2019. https://www.soundandthefuriouspod.com/episodes/2019/1/25/episode-13-environmental-racism.

Roy, Rohan Deb. "Science Still Bears the Fingerprints of Colonialism." Smithsonian Magazine, April 9, 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/science-bears-fingerprints-colonialism-180968709/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Martin Brückner, The Geographic Revolution in Early America: Maps, Literacy, and National Identity (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press and Omohundro Institute, 2006), 72–73. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Arthur S. Marks, "Joining the Past to the Present: William Rush's Emblematic Statuary at Fairmount," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 157, no. 2 (2013): 190. |

| 3. | For more on this work and its publication, see Kathryn E. Holland Braund, ed., A Concise Natural History of East and West Florida (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999). |

| 4. | Both Marks and Braund suggest that the shield's marking signifies this. For more on the publication and circulation of Romans's work, see Braund, A Concise Natural History. |

| 5. | Dominick LaCapra, Understanding Others: Peoples, Animals, Pasts (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018), 165. |