Overview

Jason Morgan Ward reviews Melanie S. Morrison's Murder on Shades Mountain: The Legal Lynching of Willie Peterson and the Struggle for Justice in Jim Crow Birmingham (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018).

Review

In 1931, an all-white jury in Birmingham, Alabama, sentenced Willie Peterson to death for a mysterious attack that left two white women dead and a third critically injured. The lone survivor identified Peterson, a black ex-miner crippled by tuberculosis, as the assailant, but many in Birmingham—black and white—doubted that Peterson could have committed the crime. Just months after launching a national campaign to save the Scottsboro Boys from a similar fate, a loose coalition of southern radicals, civil rights activists, and white liberals fought to save Peterson from the electric chair.

In Murder on Shades Mountain, Melanie S. Morrison recovers the Peterson case from the shadow of Scottsboro—arguably the most significant and certainly the most chronicled miscarriage of justice in the Jim Crow South. A social justice educator with a doctorate in theology, Morrison reveals her family connection to the case. Her father, a progressive minister born into Birmingham's upper crust, was courting Genevieve Williams when her two sisters—Nell and Augusta—were attacked on Shades Mountain, approximately nine miles south of downtown Birmingham. Augusta, along with her friend Jennie Wood, died on the mountain, while Nell survived. Truman Morrison sat on the grieving family's porch and listened to Dent Williams, the girls' brother, brag about visiting the jail after Peterson's arrest and shooting the suspect at point-blank range. Peterson barely survived to face trial, but Dent Williams dodged conviction "by reason of temporary insanity" (118).

Another form of insanity—the racial pathologies laid bare by the Peterson case—compelled Truman Morrison to break off the courtship and break rank with his wealthy family. Inspired by her father's life of activism, Melanie Morrison seeks to make sense of the stories he told her and to reconstruct the social and political world of Depression-era Birmingham. This is not an unfamiliar world for historians, as Alabama has provided the setting for a number of influential studies on race, labor, and radicalism in the Jim Crow South. Yet in shifting attention from Scottsboro's sleepy courthouse square to Birmingham's industrialized and highly stratified terrain, Morrison offers fresh perspective on the structural violence that undergirded white supremacy.

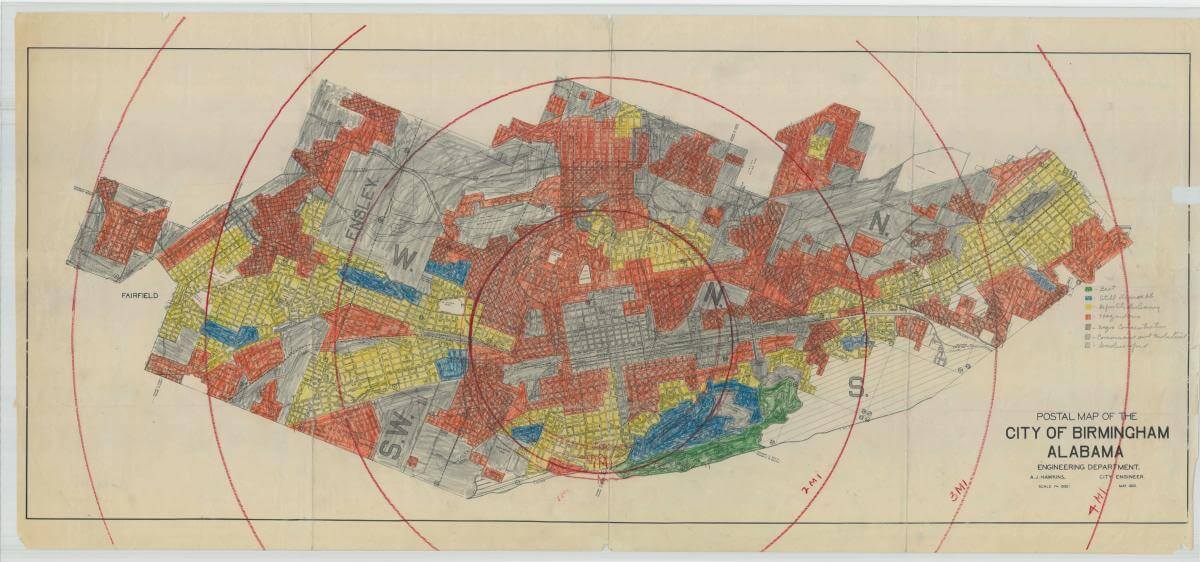

Place matters in Murder on Shades Mountain, and Morrison vividly reconstructs the social geography of Jim Crow Birmingham in the book's opening sections. Founded after the Civil War by investors intent on creating a southern industrial mecca, Birmingham was a city "rooted in racial apartheid" (26). Its barons resigned black workers to the lowest rungs of the labor ladder and confined the city's booming black population to racially zoned neighborhoods that lacked basic services. Meanwhile, whites with means moved upward and outward from the city's industrial core. The higher ground surrounding Birmingham also provided space for white leisure, including the overlook on Shades Mountain where the 1931 attack occurred. As Morrison points out, the rigidly segregated geography of Jim Crow Birmingham fueled doubts about the nature of the attack and the identity of the attacker. The notion that a black man would roam around this white enclave, in broad daylight and armed with a loaded gun, defied the spatial logic of segregation. Yet Jim Crow fueled an illogical counterpoint, where the threat of lust-crazed black men lying in wait demanded constant vigilance and swift vengeance.

The imperative that a black man must pay for the crimes committed on Shades Mountain underscores just how much Jim Crow blurred the line between legal and extralegal punishment. Angelo Herndon, a black communist and labor organizer later imprisoned in Georgia for his political activity, recounted his brutal detainment in the wake of the Shades Mountain attack. Birmingham police, he wrote in his 1937 autobiography Let Me Live, chained him to a tree and beat him with a rubber hose before charging him with vagrancy when he refused to confess to the crime. He estimated that lawmen and vigilantes killed as many as seventy black men and women in the "reign of terror" that swept him up (41–43).

For Herndon and his comrades, the arrest and prosecution of Willie Peterson marked the culmination of this broader campaign of violence and intimidation. The leftist activists who rushed to Peterson's defense blasted his conviction as a "legal lynching"—a term that Morrison embraces but which begs further interrogation given the complex and contentious history of "legal lynching" as a conceptual and rhetorical product of anti-lynching activism. Depression-era radicals were not the first to draw the connection between Jim Crow justice and extrajudicial violence, although they made these arguments vividly and forcefully. Although Morrison does not plumb this history, she rightly notes the role of US communists and allied labor radicals in promoting the argument, as the Southern Worker contended, that "the police, the courts, and the 'law enforcing' machinery are preparing to stage a legal lynching of [Peterson] as part of their campaign of terror against the entire Negro working class population of Birmingham" (84).

The rhetoric deployed in defense of Peterson echoed arguments popularized in the Scottsboro Case, through pamphlets with titles like Lynching Negro Children in Southern Courts. Published by the International Labor Defense (ILD), the communist legal aid organization that defended the Scottsboro Boys and later attempted to represent Peterson, the pamphlet typified a structural critique of Jim Crow as irredeemably violent and repressive. The ILD fought legal lynchings in the courts; its supporters—numbering several thousand in Alabama alone by the early 1930s—argued that the real fight was in the streets. Only "mass protest" would save those convicted, pamphlet author Joseph North argued, and moderates who counseled "faith in the lynch loving courts in Alabama and the South" were complicit in "hand[ing] them over to the executioner."1Joseph North, Lynching Negro Children in Southern Courts (New York: International Labor Defense, 1931).

The ILD aimed these barbs at its primary rival, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which had attempted unsuccessfully to wrest control of the Scottsboro Boys' legal defense from the radicals. That "wake-up call," Morrison notes, compelled the NAACP to intervene more quickly on Peterson's behalf (88). She characterizes the case as a moment of truth for the organization, which had struggled to regain its footing and credibility as more radical groups mobilized in response to economic crisis and white supremacist repression. The NAACP's new leader, Walter Francis White, had completed dozens of daring undercover lynching investigations, but he balked at any cooperation or association with communists on "legal lynching" cases. Nevertheless, Morrison emphasizes the NAACP's strategic flexibility and increasing emphasis on legal advocacy. Charles Hamilton Houston, the Howard University Law School dean who would become the NAACP's first special counsel in 1935, traveled to Birmingham to interview Peterson's wife, Henrietta (his notes from that encounter provided the source base for one of Morrison's most gripping passages), and advocated for the NAACP to expand its legal defense work.

Murder on Shades Mountain illuminates how the paths of some of the most significant figures and organizations in the black freedom struggle ran through Birmingham in the weeks and months after Peterson's arrest. Of course, the connections between mob violence and "legal" lynching run deeper than this slim volume conveys. While the antipathy between the NAACP and ILD infused both the Scottsboro and Peterson campaigns, the notion that racial violence represented only the most brutal expression of an oppressive system was not limited to radical organizations. "Lynching and mob violence are only methods of economic repression," the NAACP's William Pickens argued in 1921. "To attack lynching without attacking this system is like trying to be rid of the phenomena of smoke and heat without disturbing the basic fire."2William Pickens, Lynching and Debt Slavery (New York: American Civil Liberties Union, 1921). While the NAACP attempted to cooperate with southern white officials willing to speak out against lynching, including Alabama ex-governor Emmet O'Neal, they understood that such officials frequently talked down mob violence by doubling down on state-sanctioned execution. For these "law and order" officials, capital punishment offered reassurance to anxious whites that the state would dispose of black aggressors—real or imagined—without inviting negative publicity or outside scrutiny.

Peterson's death sentence offered no panacea to the Depression-era mob mentality. From the manhunt, roundups, and brutal interrogations that preceded Peterson's arrest to Dent Williams's assassination attempt on his sisters' accused attacker, the lynching spirit hovered over the case. While Peterson languished in prison, police in nearby Tuscaloosa handed over black teenagers to a lynch mob in the summer of 1933. Morrison's account reminds us that whatever divisions separated black activists, the campaign against lynching and related abuses remained a tactical and legal imperative. White reformers and civil rights activists argued over the criminal definition of lynching and the liability of local and state officials who failed to prevent it, while largely eschewing the language of "legal lynching." Even as the number of documented cases declined during the 1930s, the NAACP reported in 1940 that lynching had not disappeared but gone "underground," and warned that these secretive killings relied more than ever on the collusion of local officials.3Lynching Goes Underground: A Report on a New Technique (New York: National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, 1940), 7.

The same year that the NAACP warned that lynching had entered "a new and altogether dangerous phase," the legal lynching of Peterson ran its course.4Lynching Goes Underground: A Report on a New Technique, 7. Six years after Alabama's governor commuted his death sentence, Peterson died in the state prison infirmary from complications related to tuberculosis. Morrison describes the Peterson case as an "incomplete victory"—both in its attempt to save the man's life and in its broader challenge to white supremacy (192). Murder on Shades Mountain does not expend many pages tracing the links between this case and the more familiar Birmingham stories of the civil rights era, sparing readers of metaphors about the roots and seeds of movements to come. However, Morrison makes a point worth repeating—that "the 1930s are rife with historical antecedents to the uprisings, protests, and campaigns manifest in the 1950s and 1960s, which continues today." Despite the autobiographical bookends, in which Morrison reveals her personal connection to Birmingham's white liberal community, she emphasizes that the local movement was "led by black people" (194). Because of the historians Morrison acknowledges, and a few more she does not, we know many of these activists' names. We will never know them all, but thanks to Morrison's vivid rendering of Willie Peterson's life and witness, we know more.

About the Author

Jason Morgan Ward is acting professor of history at Emory University, where he teaches modern United States history. He is the author of Hanging Bridge: Racial Violence and America's Civil Rights Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016) and Defending White Democracy: The Making of a Segregationist Movement and the Remaking of Racial Politics, 1936–1965 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011).

Cover Image Attribution:

Boulders and road on Shades Mountain in Birmingham, Alabama, 1931–1932. Photograph by Technical Photograph Company. Courtesy of Alabama Department of Archives and History, digital.archives.alabama.gov/cdm/singleitem/collection/photo/id/33912/rec/6.Recommended Resources

Text

Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth. Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919–1950. New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc., 2008.

Goodman, James. Stories of Scottsboro. New York: Pantheon Books, 1994.

Hill, Rebecca N. Men, Mobs, and Law: Anti-Lynching and Labor Defense in U.S. Radical History. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009.

Kelley, Robin D. G. Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists during the Great Depression. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990.

Painter, Nell Irvin. The Narrative of Hosea Hudson: His Life as a Negro Communist in the South. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979.

Vandiver, Margaret. Lethal Punishment: Lynchings and Legal Executions in the South. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2006.

Web

"Alabama African-American Civil Rights Heritage Sites Consortium." Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. Accessed August 22, 2018. https://www.bcri.org/consortium/.

Behind the Veil: Documenting African American Life in the Jim Crow South. John Hope Franklin Research Center for African & African American History & Culture, Rubenstein Library, Duke University (Durham, North Carolina). Accessed August 22, 2018. https://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/behindtheveil.

Civil Rights Digital Library: Documenting America's Struggle for Racial Equality. Digital Library of Georgia, University of Georgia (Athens, Georgia). 2013. http://crdl.usg.edu.

Cornish, Audie. "How The Civil Rights Movement Was Covered In Birmingham." NPR. June 18, 2013. https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2013/06/18/193128475/how-the-civil-rights-movement-was-covered-in-birmingham.

Digital Collections: Scottsboro Boys. Gerald M. Kline Digital and Multimedia Center, Michigan State University Libraries (East Lansing, Michigan). Accessed August 22, 2018. https://lib.msu.edu/branches/dmc/collectionbrowse/?coll=21.

NAACP: A Century in the Fight for Freedom, 1909–2009. Library of Congress (Washington, DC). Accessed August 28, 2018. https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/naacp/the-great-depression.html.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Joseph North, Lynching Negro Children in Southern Courts (New York: International Labor Defense, 1931). |

|---|---|

| 2. | William Pickens, Lynching and Debt Slavery (New York: American Civil Liberties Union, 1921). |

| 3. | Lynching Goes Underground: A Report on a New Technique (New York: National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, 1940), 7. |

| 4. | Lynching Goes Underground: A Report on a New Technique, 7. |