Overview

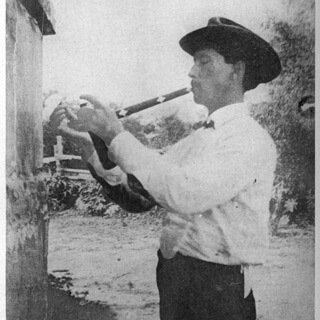

In this documentary video, Craig Womack and Steve Bransford explore the continuance of the Creek language, spoken by tribal people in Oklahoma and Florida, by centering upon the life of the Creek community leader, feminist, and activist, Rosemary McCombs Maxey. A reflective essay by Womack on the challenges and opportunities facing Creek language speakers accompanies the video.

Video

A Reflection by Craig Womack

A friend of mine tells a story about his high school days in the greater tri-city area (Wetumka, Weleetka, and Wewoka—Creek names for water that roars, runs, and barks—for those of you from parts other than rural eastern Oklahoma). One day in his Weleetka High School class, everyone stopped paying attention to the teacher and turned their eyes from the chalkboard, and United States history, to a Kafkaesque-sized cockroach making his (or her) way leisurely across the classroom floor, giant antennae twitching as it navigated its escape from secondary education.

As all of those in our noble profession know, even the most starry-eyed believer in the power of education sometimes loses control of the classroom, and this particular teacher, upon realizing her lecture had been hijacked by a very large insect, walked over to the uninvited intruder and ground it under the heel of her shoe. Given the size of the cockroach, some cleanup was in order, so she went down the hall to get paper towels from the restroom. On the way back, she heard all kinds of cheering coming from her class. While she had been out, the cockroach had reanimated and was making a second beeline, so to speak, for the door. If not for her puzzlement over all the commotion, the teacher might have nailed it again, but the cockroach reached safety, while all the Indian kids in the class cheered it on!

I don't care to judge the historical veracity of this wonderful tale, but it seems to me the Mvskoke Creek language might have about as much chance for survival as that cockroach, and I will leave it up to the reader, and the film viewer, to interpret whether or not I am suggesting that a miracle is needed or that miracles sometimes occur.1The official name of the tribe located in present-day Oklahoma is the Muscogee Creek Nation. The word, in the language, for what Creek people speak is "Mvskoke," pronounced the same as the word for the tribe. Some Creeks prefer the name "Mvskoke" since "Creek" is a name given to the tribe by the English in the Colonial era.

For sure, the dominating force of English surrounds us. People in Creek country say there are five thousand Creek speakers left, but nobody seems to know where that number comes from, and many suggest there are only a few hundred speakers, some even far fewer. This documentary, Hearing the Call: The Cultural and Spiritual Journey of Rosemary McCombs Maxey, features a Creek community leader who is determined to speak the Creek language every day—to people, when possible, and to llamas, chickens, cats, and dogs, when not.

Four years ago, I was approached by Stefanie Pierce, at that time the administrative assistant in the Department of Environmental Sciences at Emory University, who said she was talking to people about making a documentary on Rosemary. The project immediately struck me as having merit, because women in the Creek Nation are seldom given public recognition for their knowledge and contributions, especially in the realm of language and culture where women have been both instrumental as well as often ignored. In Rosemary's case, as Hearing the Call attests, she possesses multi-generational knowledge about community genealogies predating Creek Removal from ancestral homelands in Alabama and Georgia in 1836 as well as a command of specific family histories in Oklahoma Creek churches that goes back to the 1840s, when her family first started becoming leaders in these places of worship. Add to this her history working in Indian Country outside the Creek Nation, among Lakota people in South Dakota, for example; as an advocate for Native Hawaiian prisoners incarcerated in Oklahoma and Arizona; as an interim pastor for a year at Community of Hope, Tulsa's GLBTQ church; as a pastor of various United Church of Christ congregations on the East Coast; and as a person in critical dialogue with leading feminist, race, and theological scholars in the 1970s and 1980s, and it becomes evident that the subject of our documentary has more stories than we could ever put up on the screen.

As I, along with Rosemary herself and a group of Creek language advocates, watched the story unfold when Hearing the Call premiered at Emory earlier this year, it felt like its own kind of coming out story, albeit in this case the story of a kid who, rather than announce to her parents she is gay, instead tells them she's called to be a preacher—even though no such role exists for women in the denomination she grew up in. What strikes me as an incredible act of the imagination seems like something else the way Rosemary tells it: being around preachers was the only thing she knew, so as far back as she can remember she practiced sermonizing on farm animals. I don't know if Rosemary would have ground the cockroach into oblivion, had it shown up during one of her childhood church services on back porches and in farm wagons, but, having known her for many years, I feel confident that it wouldn't have escaped without being addressed at length in the Creek language, and I don't hesitate to imagine it coming up to the altar to be saved.

What is the Creek language, anyway? Without getting too complicated, let's just say it is one of the original languages of the US Southeast, and since I am an Emory professor, I will add that it is the first and foremost language of the campus where I teach. Creek people lived at Emory's exact location prior to the 1820s, having been forced out of the area earlier before the removal of the main body of the tribe that occurred in 1836, the year of Emory's founding. When I am on campus, therefore, I simply have to look where I am stepping if I want to know where the Creek language originates.

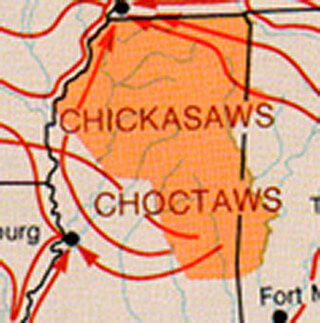

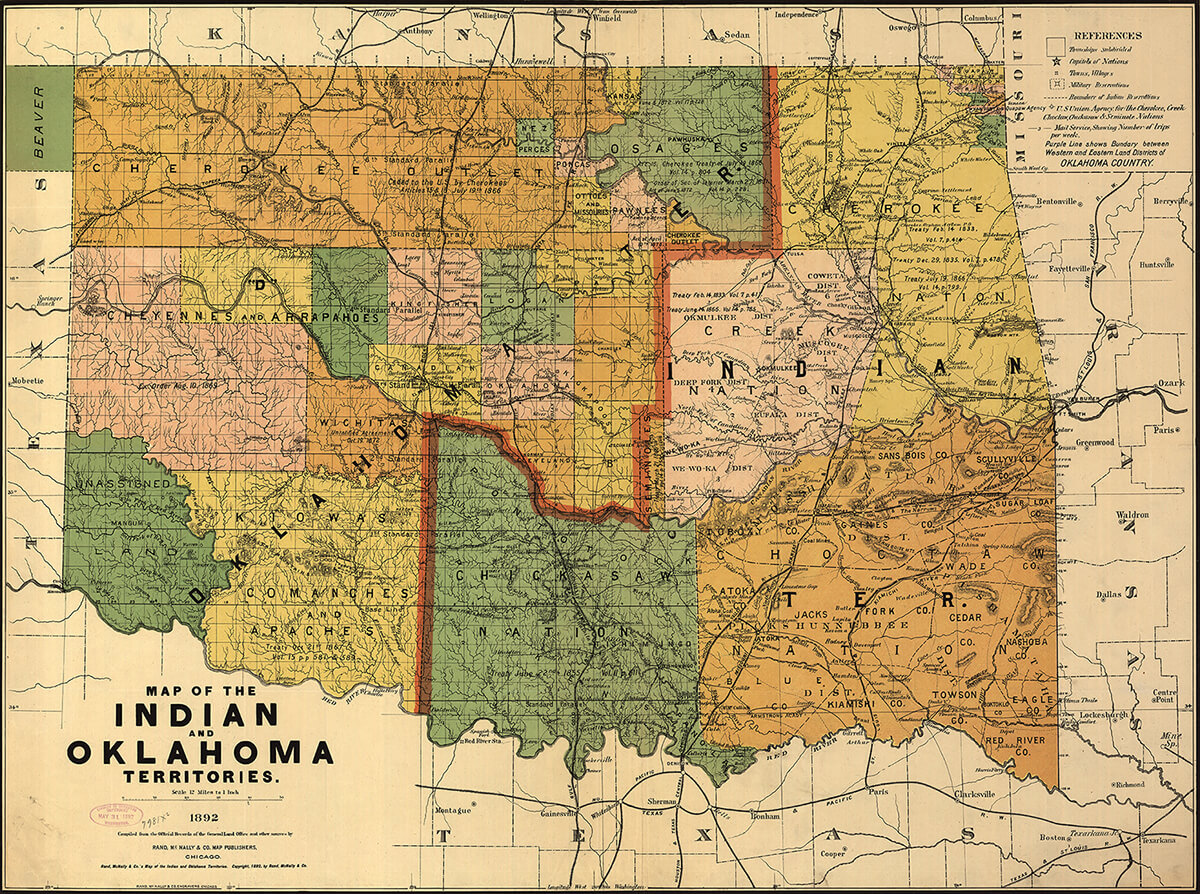

The language was originally spoken throughout Alabama and Georgia, and in the late 1700s and into the early decades of the nineteenth century, it spread into Florida through Creek-speaking groups that migrated there and now live on the Seminole reservations and elsewhere in Florida. In 1836 when the tribe was forcibly removed from Alabama and Georgia to the present-day state of Oklahoma, the language moved into what was then known as Indian Territory, a sovereign entity set aside for the exiled tribes sent there. Today, the language is primarily spoken by Oklahoma Creeks, Oklahoma Seminoles, and Florida Seminoles.

The first university course in the Creek language took place at the University of Oklahoma in the fall of 1991. As fate would have it, I was in that course. A non-Indian graduate student in anthropology, Pam Innes, was the instructor of record, and she was working with the Creek ceremonialist Linda Alexander and her daughter, Bertha Tilkens, both active members of Greenleaf Ceremonial Ground. I remember three things very vividly from that first effort. First, a Creek/Comanche friend of mine, who sat next to me, would rail after every meeting: "How can we have this non-Indian, who doesn't speak the language, trying to teach us how to speak Creek?" I didn't feel inclined to disagree. Secondly, there was constant writing and erasing, the instructors' hands working at cross-purposes, as Pam would write down a verb she had Linda conjugate, then leave it on the board; the next time Linda conjugated the verb it would be totally different, due to the infinite contextual factors that change Creek verbs. Thirdly, though we had no cockroaches for entertainment, Linda had her own way of hijacking a classroom through hilarious and raunchy stories that I have never quite gotten over and hope I never will. I am happy to report that the collaboration between Pam, Linda, and Bertha evolved into a respectful and reciprocal alliance, a friendship I have always been grateful to have been caught up in.

Since these tenuous beginnings, when academics were speculating about how Creek language worked, often relying on the meticulous fieldwork of the linguist Mary Haas, who worked in Oklahoma in the 1930s, and basing their guesses on Mary Haas's guesses, the Creek language has come a long way in terms of formal analysis. A significant part of the progress has involved checking and analyzing this earlier linguistic work with a large cohort of contemporary Creek speakers.

Pam Innes's collaboration produced a Creek grammar—Beginning Creek: Mvskoke Emponvkv (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004)—which followed a Creek-English dictionary published in 2000 by the linguist Jack Martin, who worked collaboratively for a decade with Creek elder Margaret Mauldin. By the new millennium, classes had spread from the University of Oklahoma to Oklahoma State, campuses where significant numbers of Creek students are enrolled. Martin's own work would expand tremendously with grammars, Creek-to-English translations of stories, innovative interviews of Creek elders by other Creek elders in the Creek language, videos of Creek Christians singing hymns in Creek, and much more.

While all of this has gone on at the level of formal study, the community's ability to produce young Creek language speakers is a dire situation. The tribe faces two major challenges: getting long-term immersion programs started, and the even more daunting chore of creating environments where immersed kids have some place outside the immersion classroom to practice their language skills. It is simply a fact that young kids surrounded constantly by a second language will learn it, but how do you create people for them to speak with? Can this really be done? In comparison, the cockroach might have had it easy.

Questions abound. Numerous tribes no longer have any native language speakers. Does this mean the tribe no longer has an easily definable cultural identity, or can they find new ways to identify as Indian? What, exactly, is contained in language, and to what extent do non-linguistic factors also carry culture? To what degree can English, a language spoken by almost every Indian in the United States and English-speaking Canada, also be considered an Indian language at this point? What does the Chickasaw poet Linda Hogan mean when she writes, "[b]lessed are those who listen / when no one is left to speak"?2Linda Hogan, "Blessing," in Calling Myself Home (New York: Greenfield Review Press, 1978), 27.

Rosemary McCombs Maxey still has people to talk with in Creek, farm animals who get dinner and a language lesson at the same time, Skype meetings with Creek academics in which we work together on bringing increasing levels of Creek language into our writings, and many other ongoing conversations throughout Creek country. We listen, and, since we come from a culture that prizes call and response, we hope to echo back some of what she has taught us. As for our cockroach, I don't know if it had anything akin to a language, but it did have witnesses who wanted it to survive, and we hope Hearing the Call bears witness to the power of resistance and continuance.

About the Directors

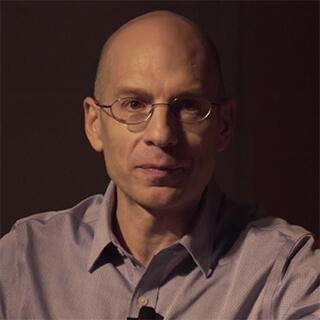

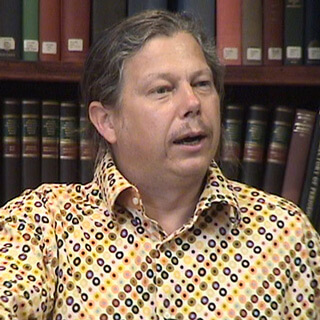

Craig Womack is an Oklahoma Creek-Cherokee Native American literary scholar, writer, and teacher, and an associate professor of English at Emory University. He is the author of Red on Red: Native American Literary Separatism (1999), Drowning in Fire (2001), and Art as Performance, Story as Criticism: Reflections on Native Literary Aesthetics (2009). He is co-author of American Indian Literary Nationalism (2006) and Reasoning Together: The Native Critics Collective (2008). He is currently working on a novel about a young musician in Northern Minnesota and his obsession with the Oklahoma folk singer Woody Guthrie. Steve Bransford is a Senior Video Producer at the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship.

Cover Image Attribution:

Rosemary McCombs Maxey, Dustin, Oklahoma, 2015. Screenshot from Hearing the Call courtesy of Southern Spaces.Recommended Resources

Text

Chaudhuri, Jean and Joyotpaul Chaudhuri. A Sacred Path: The Way of the Muscogee Creeks. Los Angeles: University of California, Los Angeles, 2001.

Deer, Sarah and Cecilia Knapp. "Muscogee Constitutional Jurisprudence: Vhakv Em Pvtakv (The Carpet Under the Law)." Tulsa Law Review 49, no. 1 (2013): 125–181.

Ethridge, Robbie. Creek Country: The Creek Indians and Their World. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Foerster, Jennifer Elise. Bright Raft in the Afterweather. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2018.

Foerster, Jennifer Elise. Leaving Tulsa. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2013.

Gouge, Earnest. Totkv Mocvse/New Fire: Creek Folktales. Edited by Jack B. Martin and Margaret McKane Mauldin. Translated by Juanita McGirt. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004.

Haveman, Christopher D., ed. Bending Their Way Onward: Creek Indian Removal in Documents. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018.

Loughridge, Robert McGill and David M. Hodge. English and Muskokee Dictionary. Philadelphia, PA: The Westminster Press, 1914.

Martin, Jack B., and Margaret McKane Mauldin. A Dictionary of Creek/Muskogee. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000.

Oliver, Louis Littlecoon. Chasers of the Sun: Creek Indian Thoughts. Greenfield Center, NY: Greenfield Review Press, 1990.

Oliver, Louis Littlecoon. Estiyut Omayat: Creek Writings. Muskogee, OK: Indian University Press, 1985.

Posey, Alexander. The Fus Fixico Letters: A Creek Humorist in Early Oklahoma. Ed. Daniel F. Littlefield Jr. and Carol A. Petty Hunter. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993.

Web

"Archives." Mvskoke Media. Accessed April 23, 2018. https://mvskokemedia.com/archives.

Gometz, Anne E. "A Creek Indian Bibliography." Anne Gometz's Requisite Homepage. April 18, 2018. https://www.rhus.com/Creeks.html.

"Mvskoke Language Program." The Muscogee (Creek) Nation. Accessed April 23, 2018. https://www.mcn-nsn.gov/services/mvskoke-language-program.

"OLAC Resources in and about the Creek Language." Open Language Archives Community. Accessed March 24, 2018. http://www.language-archives.org/language/mus.

Ruckman, S. E. "Language Preservationists in Oklahoma Scramble to Revive Endangered Tribal Tongues." Indian Country Today. May 17, 2011. https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com/news/language-preservationists-in-oklahoma-scramble-to-revive-endangered-tribal-tongues.

Shannon, Susan. "Muscogee Creek Hymns Influenced by Concretional Line Singing?" KGOU. November 17, 2014. http://kgou.org/post/muscogee-creek-hymns-influenced-congregational-line-singing.

Similar Publications

| 1. | The official name of the tribe located in present-day Oklahoma is the Muscogee Creek Nation. The word, in the language, for what Creek people speak is "Mvskoke," pronounced the same as the word for the tribe. Some Creeks prefer the name "Mvskoke" since "Creek" is a name given to the tribe by the English in the Colonial era. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Linda Hogan, "Blessing," in Calling Myself Home (New York: Greenfield Review Press, 1978), 27. |