Overview

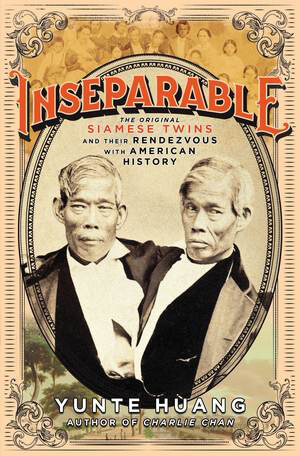

In the following excerpt from Inseparable: The Original Siamese Twins and Their Rendezvous with American History (New York: Liveright, 2018), Yunte Huang investigates the history, implications, and contradictions of Chang and Eng Bunker's ownership of African American slaves.

Excerpted from Inseparable: The Original Siamese Twins and Their Rendezvous with American History by Yunte Huang. Copyright © 2018 by Yunte Huang. Used with permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Introduction

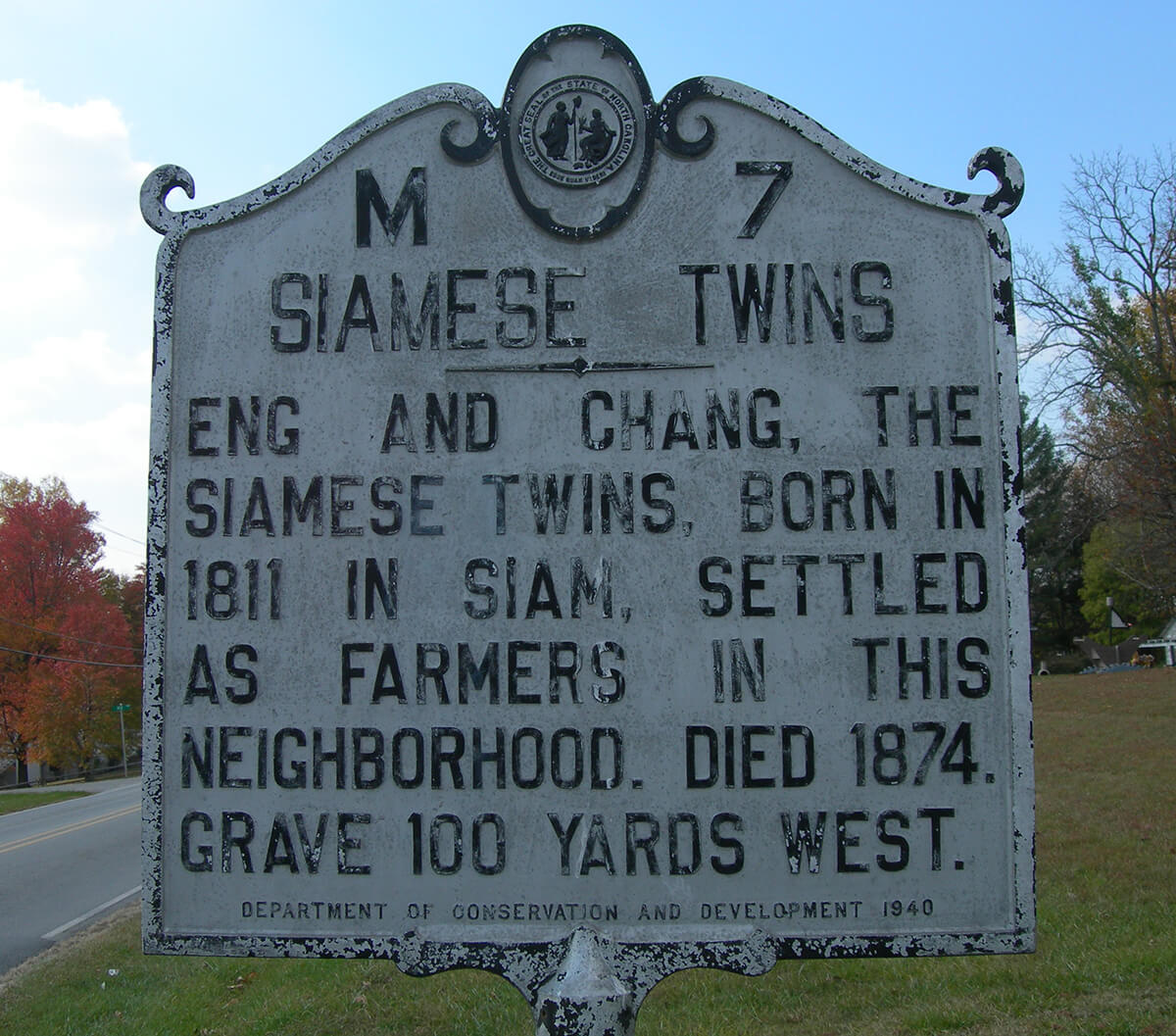

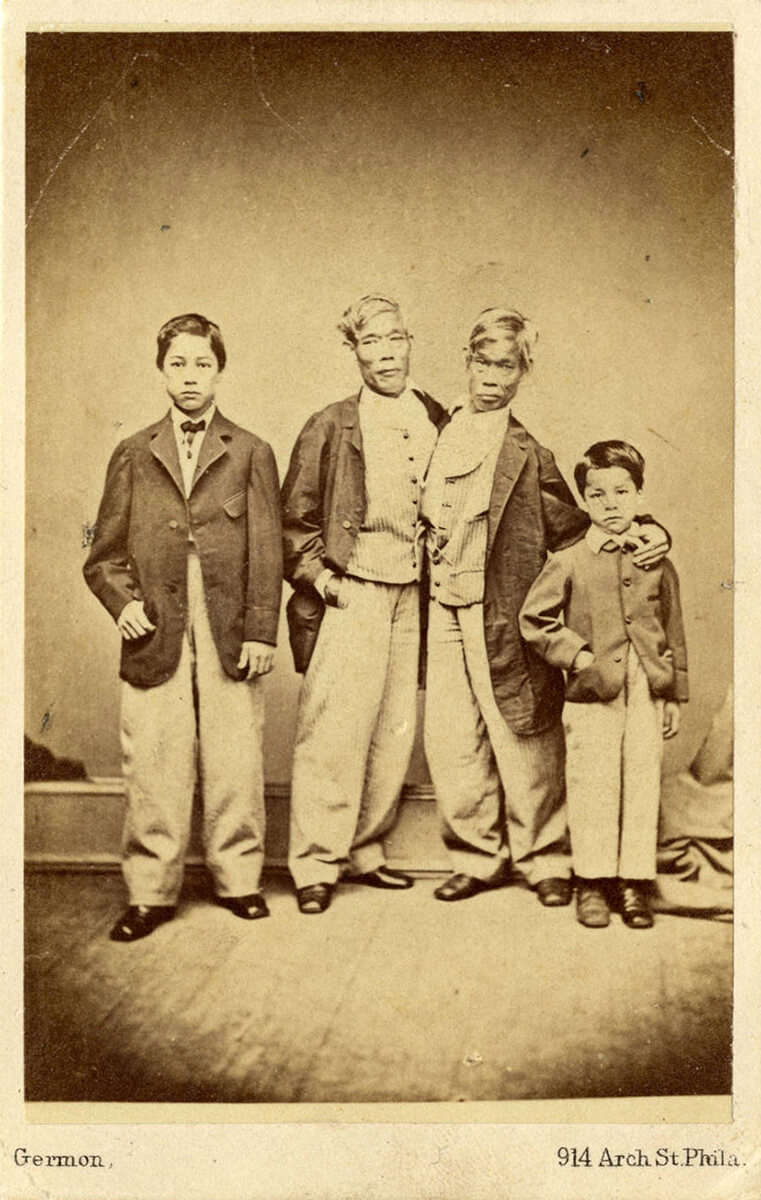

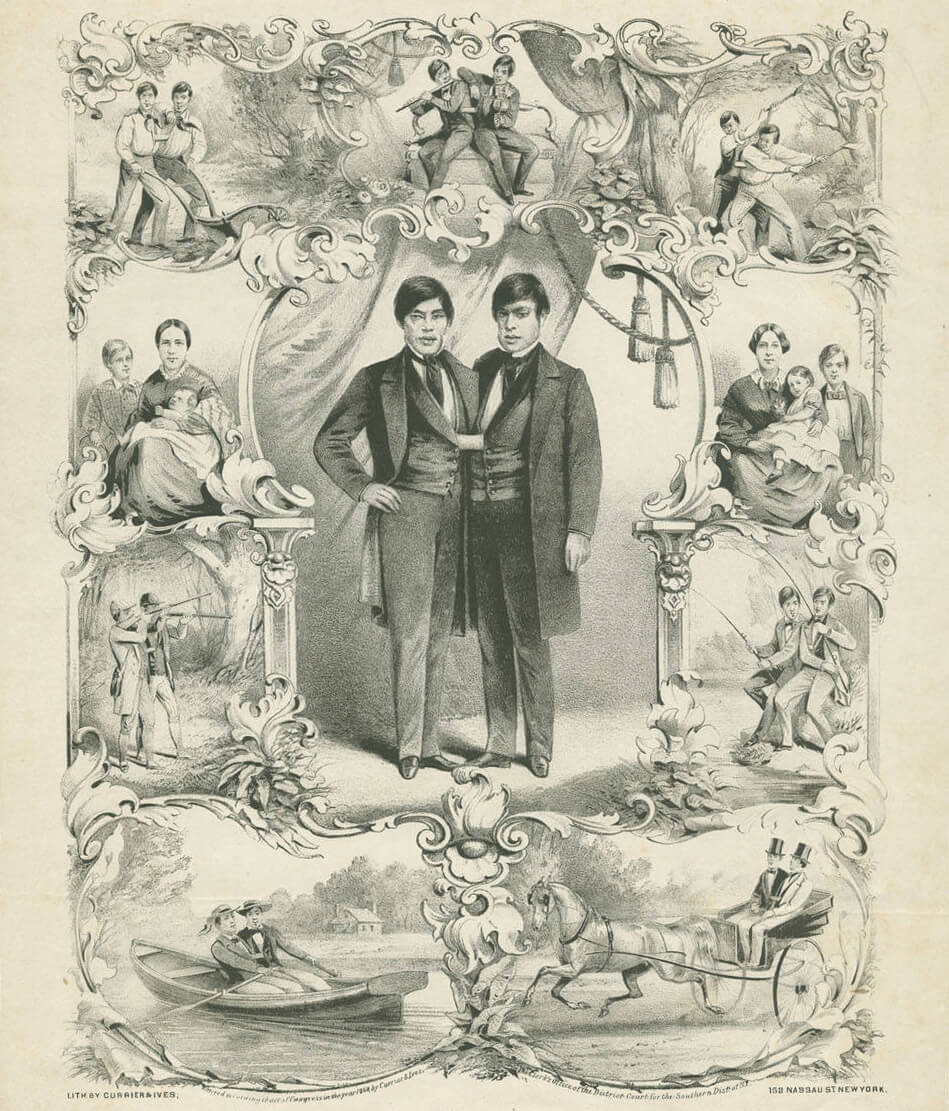

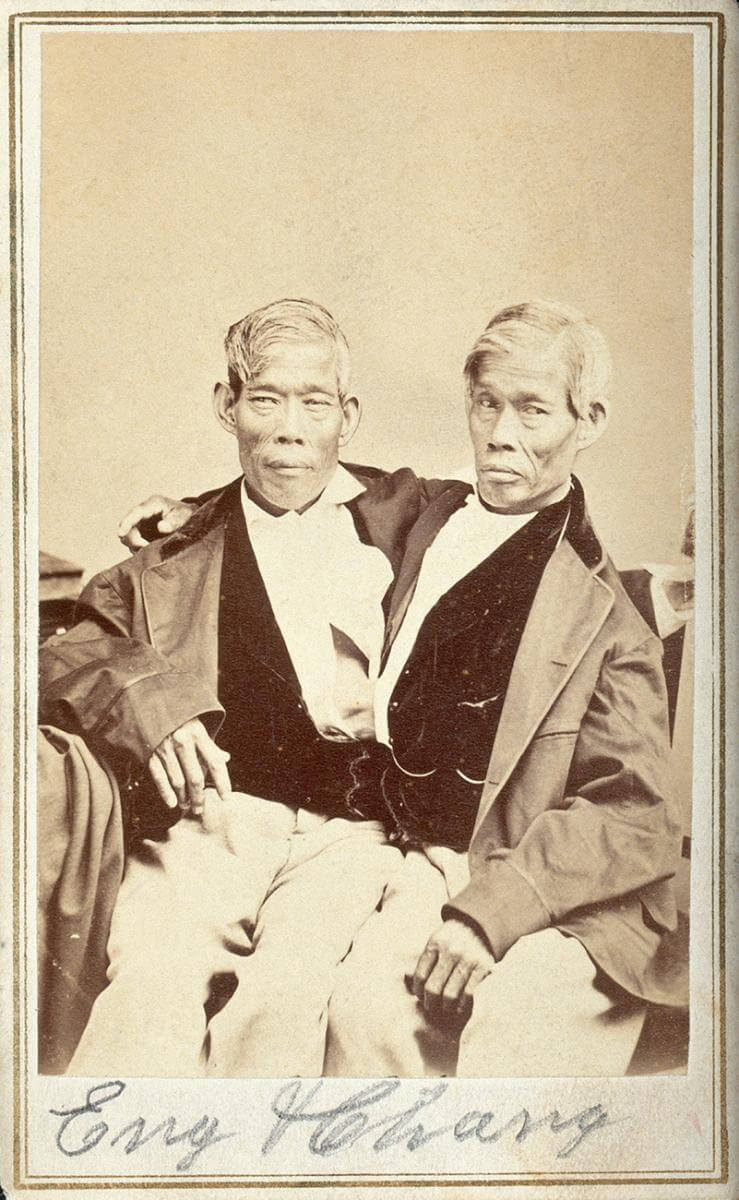

Born in 1811 on a riverboat in Siam, Chang and Eng, the original Siamese Twins, were brought to America in 1829 for a touring exhibition as freaks. They soon broke free from their enslaving masters and ran the show by themselves. Having made a fortune in a decade, they retired to western North Carolina, bought land, built houses, married two white sisters, and owned slaves. Yunte Huang's new book, Inseparable: The Original Siamese Twins and Their Rendezvous with American History, tells the gripping story of how Chang and Eng, an odd pair, beat impossible odds, living their conjoined life with grit and gusto. In this excerpted chapter, "Mount Airy, or Monticello," Huang investigates the history, implications, and contradictions of Chang and Eng's ownership of African American slaves.

Excerpt: Mount Airy, or Monticello

"She was a slave, and salable as such."

—Mark Twain, The Tragedy of Pudd'nhead Wilson

Allow me to fast forward 160 years in our story and describe an event of which the seed, like everything else, was sown in the past. In July 2003, about a hundred descendants of the Siamese Twins congregated in Mount Airy, North Carolina, for their Bunker reunion. A tradition that began years ago, the annual gathering is always held on the last weekend of July, at the White Plains Baptist Church, which the twins had helped build with their bare hands on a hill adjacent to the farmland that still belongs to the family. By some estimates, there are about fifteen hundred Bunker descendants today, spread throughout the world, although most of them have stayed close to their ancestral haunt in North Carolina.

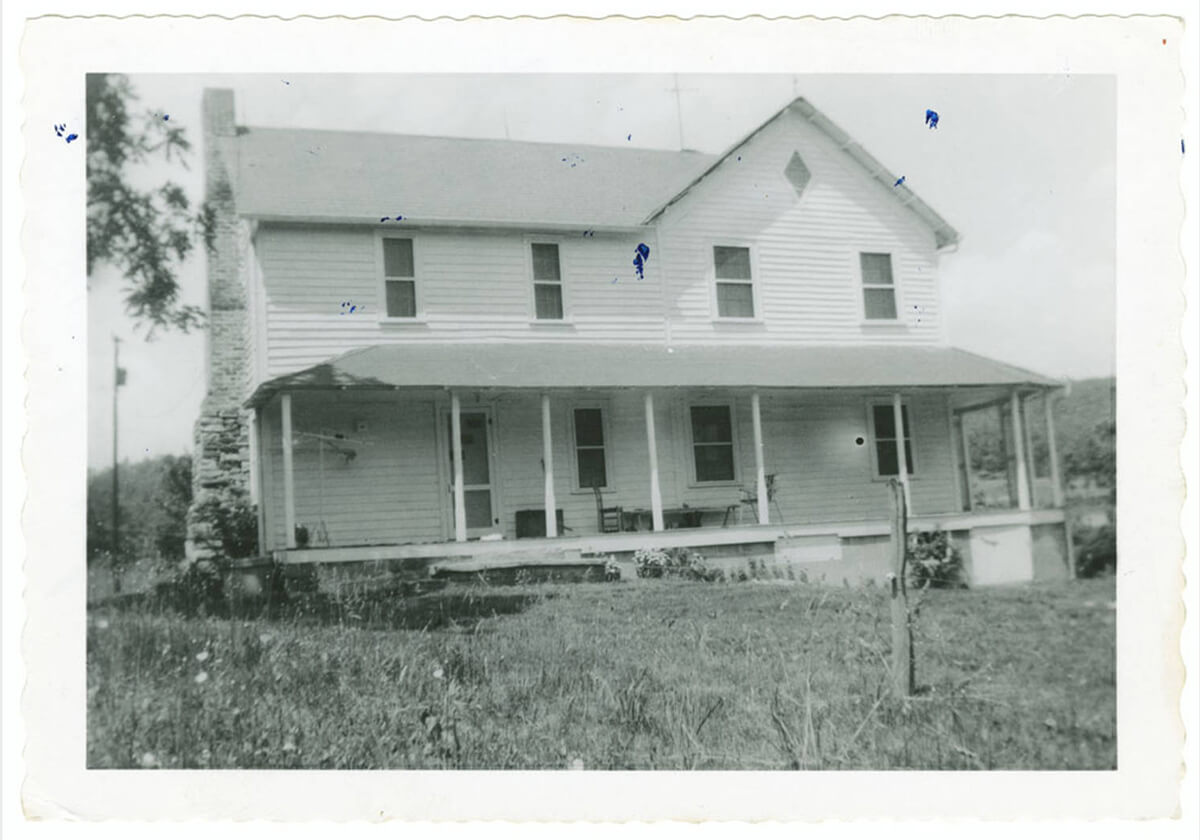

Like most family reunions, the festivities consist of a potluck buffet, speeches, and updates on the clan news. One year, they even watched a show about their illustrious ancestors, the Burton Cohen play, The Wedding of the Siamese Twins, which had premiered on Broadway in March 1988. A field trip to the twins' original homestead, now retooled as Mayberry Campground to attract from all over the world diehard fans of Sheriff Andy and Deputy Fife (more on that later), is also on the program. Journalists from the local media, following a tradition that began with the twins' arrival in this area in 1839, are usually in attendance. Sometimes, researchers and historians are also present as honored guests. The Bunkers are a convivial, welcoming bunch.

At the family jamboree in 2003, however, something unexpected happened. An African American named Brenda Ethridge stepped up to the microphone. She introduced herself as a descendant of Aunt Grace, the first slave owned by Chang and Eng. Ethridge had learned of her connection to the famous twins through stories passed down in her own family but had never been able to verify the details. Nor did she know much about her distant ancestor, who is buried in the same cemetery as Chang and Eng, along with generations of their offspring. According to Cynthia Wu, a Chinese-American historian who was present at this reunion, the sudden appearance of an African American in their midst hit a nerve. While Ethridge was a welcome presence for most on that occasion, a flurry of exchanges ensued among several concerned Bunkers, museum curators, and DNA experts. Only six years had elapsed since the official confirmation that Thomas Jefferson had fathered children with his slave Sally Hemings, and that subject was still hanging in the air. Across the state line, it seemed, the ghost of Monticello lingered in Mount Airy.1Cynthia Wu, Chang and Eng Reconnected: The Original Siamese Twins in American Culture (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012), 163–65.

To understand how we arrive at this juncture, or how the conjoined brothers could have spawned thousands of offspring, and why a black woman would challenge the veracity of their genealogy, we need to return to the mountain wedding in 1843, to the quiet house that today still stands in Traphill, where the Bunker clan, as a quintessentially American, multiracial family, was just getting started.

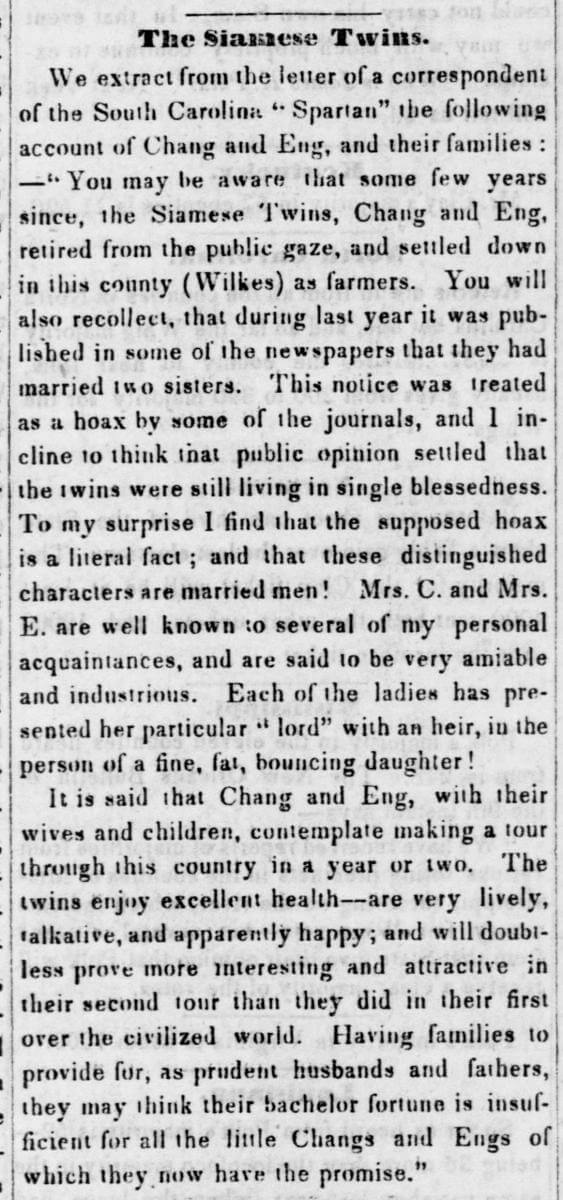

At the time of the twins' wedding, some local folks wagered over how long the marriage could last and whether such a "freakish union" would produce any offspring. In their mind, bestiality was godforsaken, unnatural, and surely doomed to infertility. They also wondered how long the Yates sisters could stand the ignominy of having to bed two swarthy Asian freaks. James Hale predicted that unless the twins were separated, the marriage would not stand a chance. "Depend upon it," he wrote to Charles Harris, "the result will be, a desire to attempt a surgical operation upon themselves."2James Hale, letter to Charles Harris, July 27, 1843, North Carolina State Archives.

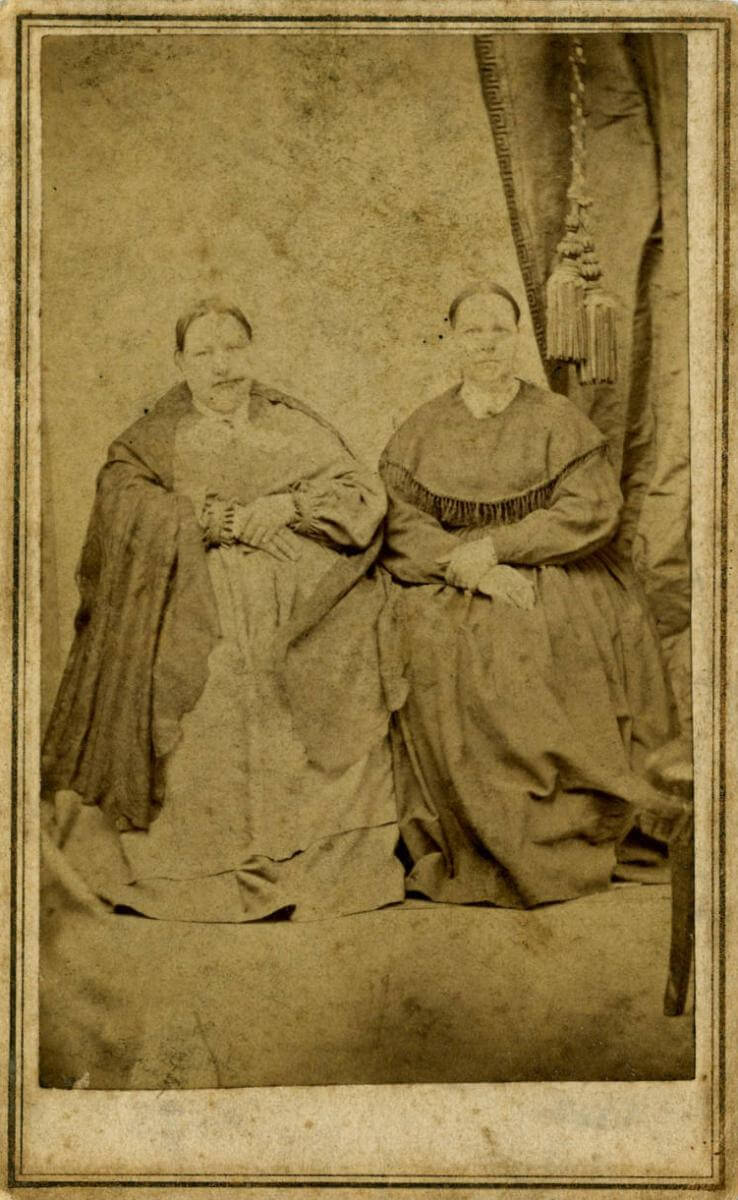

Those skeptics might have been surprised to know that the twins had indeed considered surgically untying themselves so that they could lead "normal" lives with their respective wives. It was their wives, however, who vehemently opposed such a move. According to some biographers, the twins, prior to their wedding, had consulted with physicians in Philadelphia and were ready to go under the knife. Aghast at the news, Sarah and Adelaide begged the men not to follow through with the dangerous procedure and reassured the men that they would be happy to marry them "as they were."

The skeptics must have been even more surprised when they heard, ten months after the wedding, that each couple had produced a "fine, fat, bouncing daughter." On February 10, 1844, Sarah and Eng became proud parents of a baby girl named Katherine; only six days later, Adelaide and Chang welcomed into the world a baby girl named Josephine. If there was any lingering doubt about the procreative aspect of the unions, there would be even more evidence to put the matter to rest: In their lifetime, the two couples would produce twenty-one children in total, with Eng and Sarah claiming eleven and Chang and Adelaide, ten. Out of these twelve daughters and nine sons, two would die at young ages from accidents, while two were deaf and mute. There were no twins, let alone conjoined twins or babies with any other discernible deformity.

Twenty-one children for two couples may seem extraordinary and could possibly feed into some of the prevailing stereotypes that portrayed primitive "Orientals" engaging in bestial sex and breeding like animals. Thomas de Quincey, if we remember, called the Asian continent the "workshop of men." Herman Melville, hardly conventional in his choice of bedfellows, imagined in Moby-Dick that those ghostly aboriginals "of earth's primal generations" in insulated Asia "engaged in mundane amours."3Herman Melville, Moby-Dick, ed. Harrison Hayford, Hershel Parker, and G. Thomas Tanselle (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press and Newberry Library, 1988), 231. In reality, however, it was not unusual for a couple living in the Appalachians during this era to have a score of children. Visiting the area in 1828, Dr. Elisha Mitchell, the geologist who had earlier given us the on-the-ground account of the lay of the land in Wilkes and neighboring counties, was struck by the "swarms" of children he encountered everywhere—a phenomenon confirmed by studies of demographics and birth rates. As Martin Crawford points out, "Families with ten or more offspring were common in this period." One couple from northwestern North Carolina produced eighteen children in the decades straddling the Civil War, while another couple had seventeen. One woman, Jane Richardson, "was reported in 1855 as possessing no less than 174 living children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren."4Martin Crawford, Ashe County's Civil War: Community and Society in the Appalachian South (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001), 2.

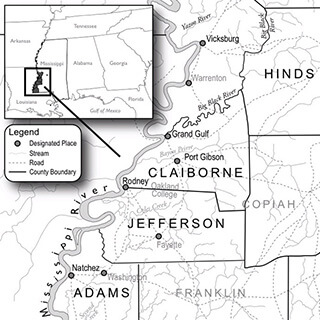

A year after the birth of their first children, the twins and their wives celebrated the arrival of two more additions to the brood, born again only about a week apart: a baby girl named Julia for Eng and Sarah on March 31, 1845, and the first boy, named Christopher, for Chang and Adelaide on April 8. As the family grew, the house in Traphill became too small for them. In the spring of that year, Chang and Eng purchased a farm in nearby Surry County for $3,750. Straddling bubbling Stewart's Creek outside the village of Mount Airy, this 650-acre farmland would become their Xanadu—or, more pertinent and closer to home, their Monticello.

On this new land, Chang and Eng—two brothers formerly sold into indentured servitude and treated no better than slaves—began farming by using black slaves. Here our story takes a significant turn, entering what Primo Levi called "the gray zone" of humanity, a treacherously murky area where the persecuted becomes the persecutor, the victim turns victimizer.

The first slave Chang and Eng owned, as mentioned earlier, was Aunt Grace, the ancestor of Brenda Ethridge, who attended the 2003 Bunker reunion. Legally known as Grace Gates, and born a slave in Alabama around 1790, Aunt Grace was sold to North Carolina at a young age and became the property of David Yates. Chang and Eng received her as a "wedding gift," the same way that the nameless black servant standing behind Alabama circuit judge Sidney Posey, presiding over the assault case against the twins years earlier, had been a wedding present from the young judge's in-laws. Known for her exceptionally large feet, Grace would assume the slave–nanny role and exert a large influence in the twins' family, nursing all of the Bunker children as well as her own.

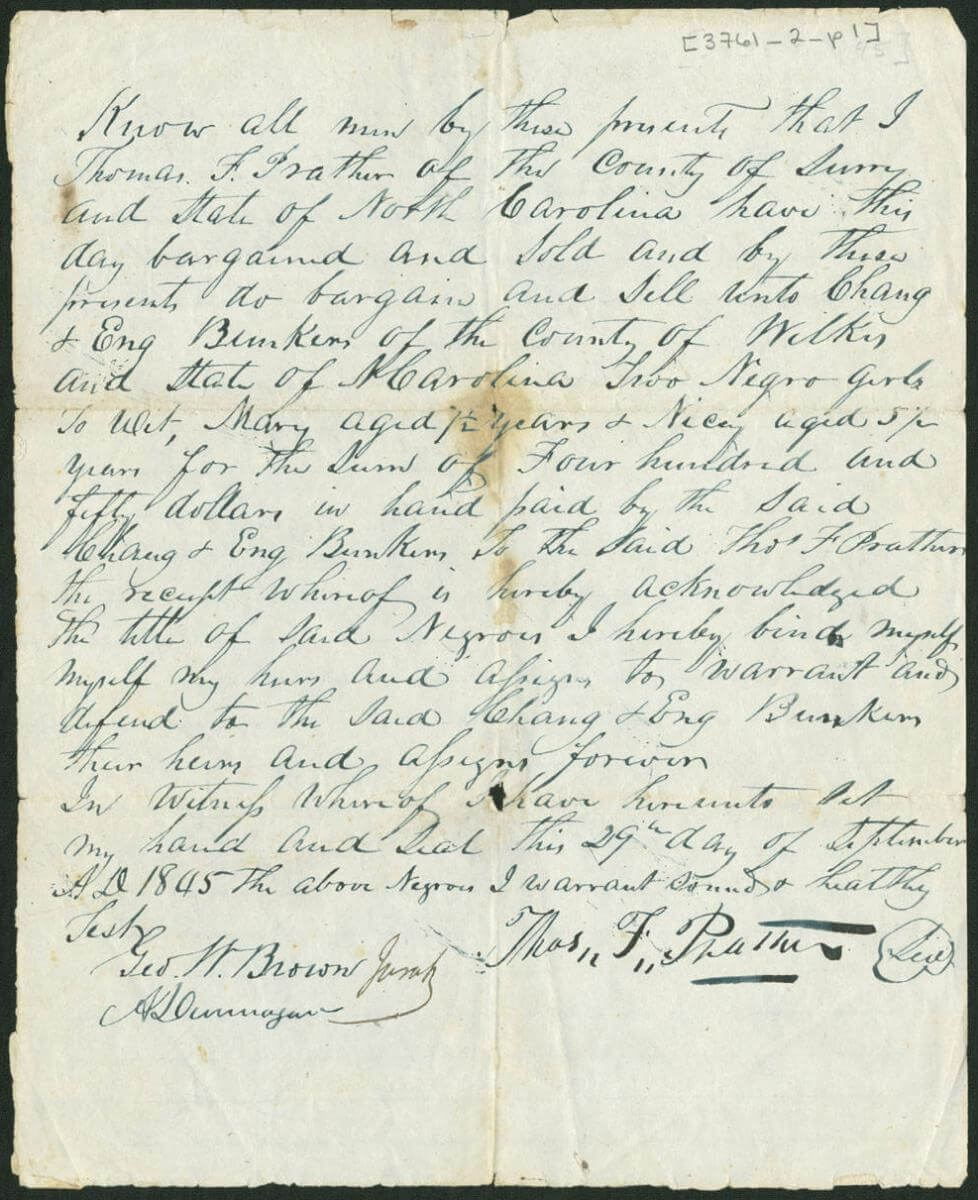

Soon after their relocation to Surry County, the twins began to purchase more slaves and even engage in slave trading. What is unquestionably clear is that the twins by this time had adopted the mindset, in all its permutations, of the oppressor class, the whites who owned slaves. In September 1845, they bought from Mount Airy planter Thomas F. Prather two black girls, aged seven and five, for $450, and from another neighbor a three-year-old boy for $175. Within just a few years, they had eighteen slaves. Out of these eighteen, according to the 1850 census, more than half were younger than eight years old. As Judge Graves admitted candidly, "Some few of their slaves were valuable to them for their present ability to labor; but much the greater number of them were an absolute burden but very valuable on account of the marketable price and prospective usefulness."5Jesse Franklin Graves, "The Siamese Twins as Told by Judge Jesse Franklin Graves," unpublished manuscript, North Carolina State Archives, n.d., 22. According to the twins' descendant Melvin Miles, Chang and Eng would buy slaves younger than eight, keep them, and work them until they were in their early twenties, when they would be sold or traded for younger ones to carry on the work. With very few exceptions, they would not keep a male slave older than twenty-five, because "the twins thought that by then the male slaves were of the mindset of trying to escape or rebel against their owners."6Melvin M. Miles, Eng and Chang: From Siam to Surry (self-published, CreateSpace, 2013), 65. Perhaps the twins remembered the horror of the Nat Turner revolt in 1831. Female slaves, by contrast, would be kept for as long as needed, because they were less likely to run away or to rebel, and they would bring additional value when they had babies—the so-called increase. Aunt Grace, for instance, gave birth to nine children, three of whom—Jacob, Jack, and James—survived and became the property of her masters.7Evelyn Scales Thompson, Around Surry County (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2005), 14. In fact, Grace's three sons all assumed the Bunker name, according to the 1870 census.

Living in squalid cabins, the slaves were divided into "house slaves" and "field slaves." The former, including Aunt Grace, worked mostly around the houses, helping to cook, clean, sew, nurse babies, and do other domestic chores. The field slaves would rise before dawn and work in the field till sunset. How the twins treated their slaves was a contentious topic both during their lifetimes and after their deaths. There were accounts that portrayed them as humane and kind, while others described them as "severe taskmasters." According to Judge Graves, whenever the twins took long trips, they would always bring gifts for each member of the family, "not even forgetting the colored servants down to the youngest."8Graves, "The Siamese Twins," 23. In the field, they also patiently taught the slaves some of the new farming techniques they had learned from agricultural magazines. The twins were allegedly among the first farmers in North Carolina to produce "bright leaf" tobacco, and they taught the slaves how to use their newly acquired press to make "plug" chewing tobacco. Possum-hunting being one of their favorite sports, the twins would frequently take some of the slaves out with them on early mornings for expeditions, which were recreational to them but not necessarily to the slaves.

These descriptions of the so-called harmonious relationship between masters and slaves, suggesting that the twins "did not drive their slaves but supervised them," were complicated by allegations to the contrary.9Joseph Andrew Orser, The Lives of Chang and Eng: Siam's Twins in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 127. The first of these negative reports appeared in a newspaper article published in the Greensborough Patriot in 1852. The author of the article, who signed himself merely "D.," did a profile of the twins, describing them as shrewd and industrious businessmen with belligerent and fiery dispositions. He claimed that the twins had once split "a board into splinters over the head of a man who had insulted them" and were "fined fifteen dollars and costs...Woe to the unfortunate wight who dares to insult them." This prelude led to a more devastating revelation: "When they chop or fight, they do so double-handed; and in driving a horse or chastising their negroes, both of them use the lash without mercy. A gentleman who purchased a black man a short time ago from them, informed the writer that he was 'the worst whipped negro he ever saw.'"10Greensborough Patriot, October 16, 1852.

Such an unflattering depiction of them as cruel masters drew an immediate response from the twins, who were acutely aware of the importance of public image. They shot off a long letter to the newspaper, defending their own character and integrity and objecting vehemently to the article's claims:

The portion of said piece relating to the inhuman manner in which we had chastised a negro man which we afterwards sold, is a sheer fabrication and infamous falsehood. We have never sold to any man a negro as described, except to Mr. Thos. F. Prather, who denies the truth of said accusation, or of ever having told any person that which the author of said communication says he heard. We are well aware that to some who have not seen us, we are to some extent an object of curiosity, but that we were to be objects of such vile and infamous misrepresentation, we could not before believe.

Along with the letter, the twins attached an endorsement by thirteen local citizens and neighbors attesting to the truthfulness of their statement, signatories who included Thomas Prather, from whom the twins had made their first purchase of young slaves and to whom they had now sold an older one.11Greensborough Patriot, October 30, 1852.

Then there were other stories about often-poisoned relations between the twins and their slaves. One, reported years later, tells of a black slave who one day appeared at the front door of the twins' house and wanted to see them on business. While the Southern custom dictated that a "colored" man would have to use the back door of a white man's home, this black man might have thought the rule would not apply to two tawny Asians with slanting eyes. "When the Twins saw the negro standing in the front door," as the story goes, "they instantly made for him with a malignant air and the negro lost no time in taking himself away. After that he knew his place."12J. E. Johnson, "Siamese Twins," in Mount Airy News, January 3, 1956.

Another story, reported in the Mount Airy News, is about a slave who had "developed into a desperado and was considered dangerous":

He usually was a pest, for the hand of every man was against him. There was no law to protect such slaves and it was considered the proper thing to do to kill him on sight. This bad negro, the property of Chang, was reported one night to be in the negro cabins of a slave owner near Mount Airy. The citizen went with his gun to investigate and the negro ran from the cabin and as he ran the citizen red his gun intending to shoot him in the legs. But as luck would have it he aimed too high and killed the negro.

There was no law to punish him for his deed; but he saw a big bill facing him in the way of pay for the value of the dead slave. At once he went to the home of the Twins hoping to make the best settlement possible. Imagine his surprise when the Twins refused to accept a cent and expressed their satisfaction that the negro was out of the way.13Ibid.

In the antebellum South, such tragic events were certainly not rare occurrences. Nor would such conduct by a slave master raise any eyebrows. The twins themselves were said to be fond of bragging about how they had bet on slaves at card games, treating them as disposable property, no better than livestock:

One time, when they were traveling in Virginia with a neighbor, they were urged by some gamblers to join in a game of cards. They did not engage in gambling games, and so they refused. However, they agreed to back the neighbor, who was "handy with cards." The neighbor won royally, and the gamblers, in their desperation, bet "a negro." The twins won him, and then sold him back to the unlucky gamblers for $600.14Irving Wallace and Amy Wallace, The Two: A Biography (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1978), 193.

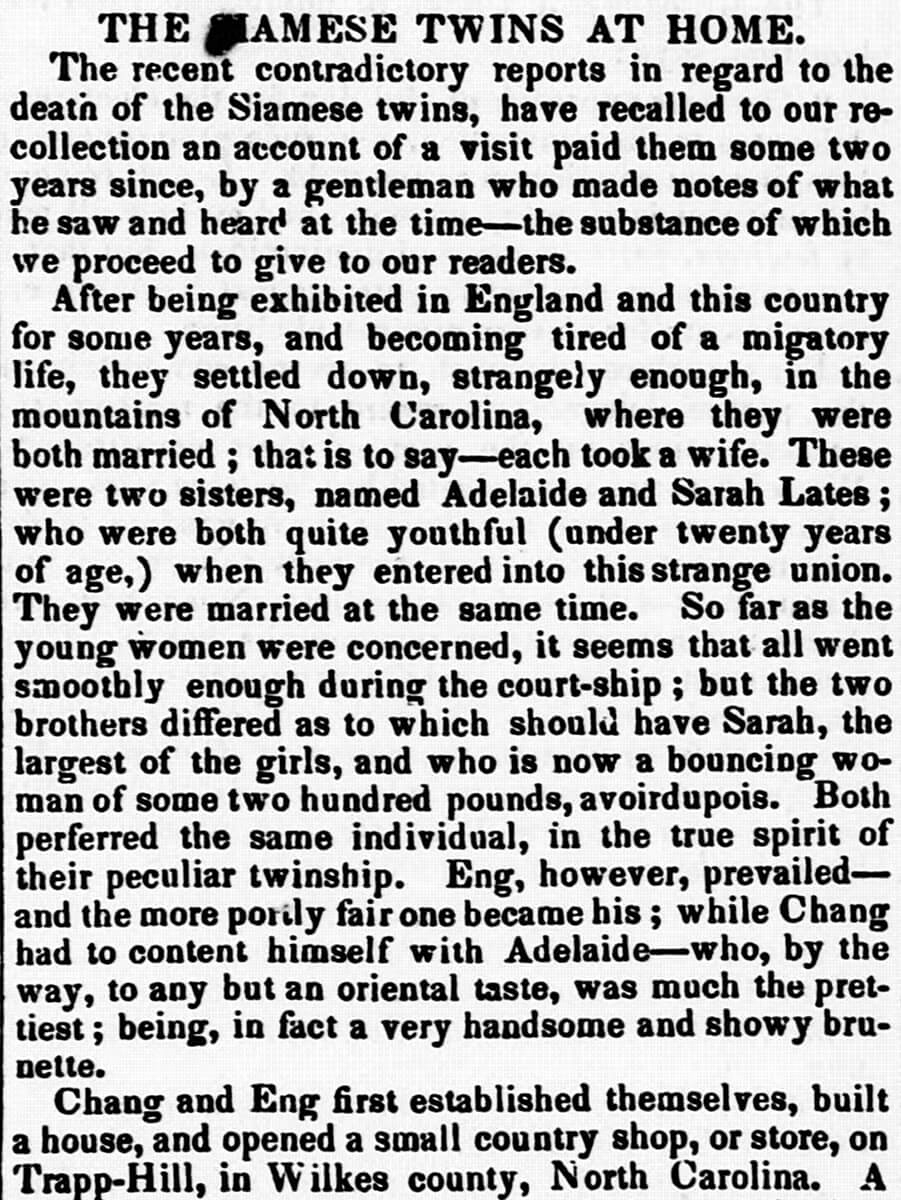

Stories like the above, both the positive and the disparaging portrayals of people treated as subhuman, starring two Asian freaks consorting with two white women and lording over a squad of black slaves, certainly had much traction in the antebellum South. They became perfect fodder for scandal-starved newspapers and readymade material for Southern Gothic, with its endless obsession with sexual peccadilloes, racial violence, deranged cravings, and morbid humor. The following profile, led in early 1850 by a curiosity-seeking journalist and featured in a publication aptly entitled The Southerner, would require very little touchup for it to fit into a plantation pastoral with decidedly racist undertones:

When we got off the stage at Mt. Airy we were told by the townspeople that the Twins were moody, sulky people and often refused to see anyone who called on them.

After a few glasses of ale and a meal at the Blue Ridge Inn in Mt. Airy we felt more in place in calling on the Twins. It was an extremely warm day and the driver gave the horses plenty of time, in addition to taking the long way around. After having arrived we drove up into a shade of a large cottonwood tree. Everything seemed quiet except a colored boy doing some metal work in a shop nearby. There was a large male peafowl strutting across the yard. Then the twins appeared in the doorway dressed in rough cotton. Each had a quid of tobacco in his mouth, each was barefooted. They stood in the doorway a minute or so, then waved good naturedly. They approached our carriage and asked how they could serve us. . .

They led us into the living room which contained a bed and other necessities. We found them to be extremely interested in farming as well as moderate conversationalists, often speaking in unbroken English. One would talk awhile then the other would take over and talk for a few minutes. A colored boy was instructed to bring in some fresh cider, which we really enjoyed.15"The Siamese Twins at Home," in Southerner, reprinted in Trumpet and Universalist Magazine, November 2, 1850.

What might otherwise pass as a run-of-the-mill antebellum encounter, in which landed Southern gentry were being served by domestic slaves while hosting visitors, was complicated by the fact that the masters in question were, simultaneously, Asian and freakish. The journalistic preamble about the twins being moody and sulky, the gothic setting of an exotic bird milling around and a "colored boy" doing handiwork nearby, and finally the dramatic entry of the real exotic bird, the conjoined twins, in the doorway, clad in coarse cotton, chewing tobacco, like some ominous creature, barefoot no less—as if reprising a scene from 1001 Arabian Nights, the most popular contraband book in colonial America—busting out of a cage, all combined to suggest something bestial, crude, scandalous.

Nineteenth-century Americans were not new to the scandal or outrage of nonwhite men luxuriating in the privilege of the slaveholding class. Prior to the arrival of the Europeans, many Native American tribes had owned slaves, though none exploited slave labor on a large scale. With the introduction of African slavery, Indian nations also participated in the practice. At the time of Chang and Eng's settlement in North Carolina, the Cherokee Nation possessed a few thousand black slaves. The wealthy family of the Cherokee chief, James Vann, owned more than a hundred in 1835.16Tiya Miles, The House on Diamond Hill: A Cherokee Plantation Story (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 87. What magnified the scandal of Chang and Eng as slave masters was their perceived monstrosity and miscegenation.

It would be hard to overestimate the enormous impact these perceptions had on the populace, both the wealthy and the poor, who lived in the vicinity of the twins' homestead and in the surrounding areas. The rich white unquestionably begrudged having to share class and status with two Asians; just consider the reaction of the twins' closest associates when Chang and Eng expressed their wishes to live the normal lives of country squires. The poor white was especially resentful and envious, his place on the social ladder suddenly at risk. Local rumor mills churned out endlessly salacious stories about the foursome that was going on by Stewart's Creek, on farmland owned by two "colored" men with slanting eyes, masters to a bunch of Negroes. The résumé of a local boy, who would later become a leading voice in explosive national issues such as abolitionism and the anti-Chinese campaign, might give us a rare glimpse into how the unusual lifestyle of the twins as slaveholding landed gentry had affected the American heart and soul.

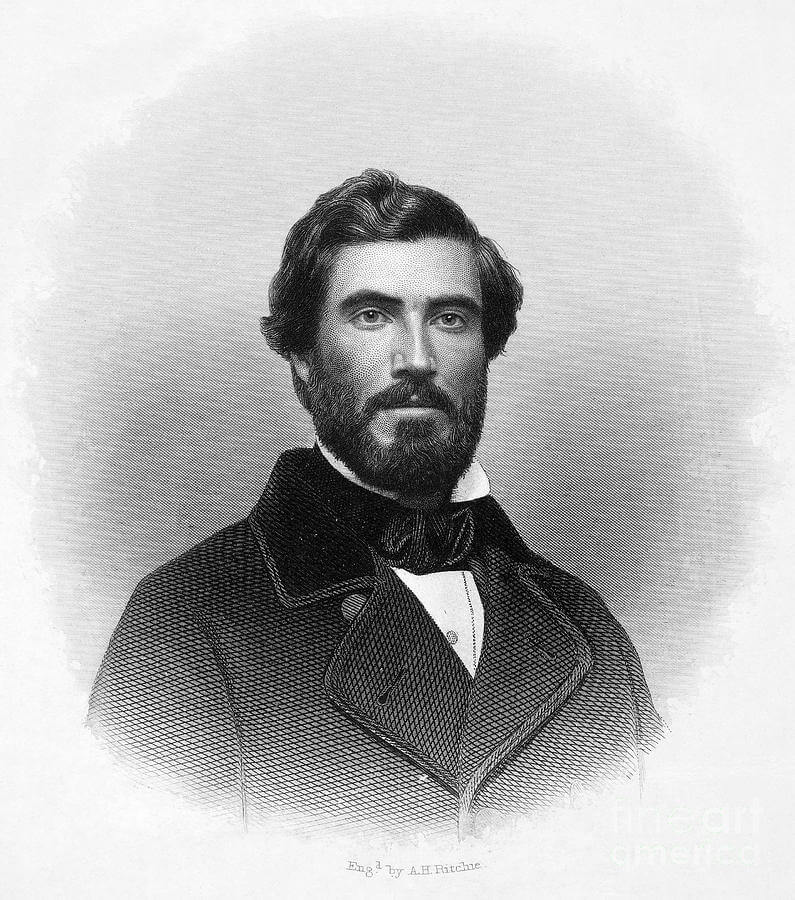

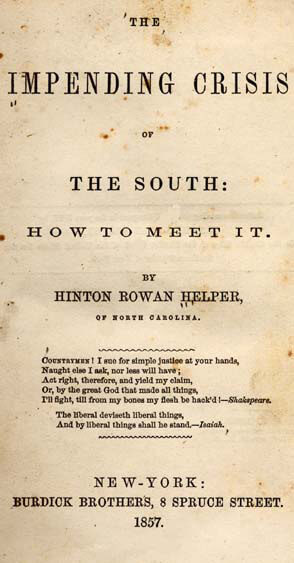

Born the same year as Chang and Eng's arrival in America, Hinton Rowan Helper (1829–1909) was the son of a struggling North Carolina farmer who owned a small plot of land and a family of four slaves in Mocksville, about sixty miles south of Mount Airy. When Helper was less than a year old, his father died from mumps, leaving his widow and seven children near poverty. Living under his mother's care until he was a teenager, Helper graduated from Mocksville Academy in 1848 and went to California in 1851 to seek his fortune. He was utterly disappointed, because he had difficulty finding a job in a region flooded with non-Caucasian immigrants such as Mexicans and Chinese. Disillusioned with his California experience, he turned to writing to vent his resentment and to prescribe a cure for what he thought had afflicted the nation. Drawing upon his three years of drifting in the Wild West, Helper's first book, The Land of Gold (1855), exposed the California dream as a hoax perpetrated by greedy financiers and inept politicians. He was particularly alarmed by the state's estimated forty thousand Chinese, whose presence offended his strong Anglo-Saxon prejudice. In a sensational chapter titled "California Celestials," he waged an all-out war against the Chinese, mocking their appearances, dismissing their habits, and condemning their immorality. "I cannot perceive," he wrote, "what more right or business these semi-barbarians have in California than flocks of blackbirds have in a wheat field." But no worries, he reasoned, because fate was against the Chinese. "No inferior race of men can exist in these United States without becoming subordinate to the will of the Anglo-Saxons," as it had been with the Negroes in the South, whose enslavement stood as the central issue in his subsequent book, The Impending Crisis of the South (1857).17Hinton Rowan Helper, The Land of Gold: Reality versus Fiction (Baltimore, H. Taylor, 1855), 75. Combining statistical charts and provocative prose, the new book attacked the evils of slavery and its devastating effects upon the people to whom the book was officially dedicated, "The Nonslaveholding Whites of the South." Enjoying popularity exceeded by no antebellum publication other than Uncle Tom's Cabin, this abolitionist tome argued that slavery ruined the South by preventing economic development and industrialization, and that it hurt the Southern whites of moderate means, who were oppressed by a small aristocracy of wealthy slaveholders.

Although there was no direct evidence linking Helper's animus toward both the Chinese and the slaveholding aristocracy to his in-person experience with the Siamese Twins, it is not inconceivable that, as Robert G. Lee suggests, "the young Hinton Helper, in addition to sharing the salacious but almost universal fascination with the imagined sexual practice of the twins and their wives, resented the fact that the Siamese twins were land owners of substance and slaveholders to boot, while Helper's own family found itself in reduced financial circumstances on its small farm as the result of his father's early death."18Robert G. Lee, Orientals: Asian Americans in Popular Culture (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999), 42. When the twins gave one of their last performances in the summer of 1839 in Statesville, ten-year-old Helper was but a few miles away. Spending his formative years in Mocksville, Helper, if he did not live within a stone's throw of Chang and Eng's domicile, certainly came of age within the earshot of all those ribald rumors that rippled through the hills and hollows of western North Carolina.

There are at least two central motifs in Helper's writings that can assist us in detecting the invisible but discernible presence of the Siamese Twins in his racial imagination. First, he was obsessed with the Chinese in California "as a deterrent to the immigration of respectable white women and thus a barrier to 'normal' family development."19Ibid. To Helper, nothing would be more abnormal as a family unit, both racially and structurally, than the abominable union of the Asian twins and their white wives. Second, Helper's belittling descriptions of Chinese people made them seem like freaks, evoking the eerie monstrosity of the conjoined twins:

[John Chinaman's] feet enclosed in rude wooden shoes, his legs bare, his breeches loosely flapping against his knees, his skirtless, long-sleeved, big-bodied pea-jacket, hanging in large folds around his waist, his broad-brimmed chapeau rocking carelessly on his head, and his cue [sic] suspended and gently sweeping about his back! I can compare him to nothing so appropriately as to a tadpole walking upon stilts.20Helper, The Land of Gold, 71.

What offended Helper's Anglo-Saxon sensibility was not just the freakish, exotic appearance of the Chinese but also the strange phenomenon that the Chinese all looked alike to him. "All their garments look as if they were made after the same pattern out of the same material and from the same piece of cloth. In short, one Chinaman looks almost exactly like another, but very unlike anybody else."21Ibid., 70. We know for sure that in mid-nineteenth-century America, no two Chinese men looked more alike than Chang and Eng, who in fact always wore clothes "made after the same pattern out of the same material and from the same piece of cloth." As Helper wandered around the city square or walked down Telegraph Hill in San Francisco, where the Chinese thronged the "cow-pens" and "human stables," as he put it, his mind might have easily been tricked by the memories of the Siamese Twins, who had undoubtedly haunted his childhood.22Ibid., 70, 55–56.

In the early 1850s, when Helper returned from the California nightmare to his humble homestead in North Carolina to nurse his injured sensibility while writing his first two books, the gentrified life of Chang and Eng in the next county was just getting more complicated. Since 1844, each twin and his wife had increased their brood at a steady pace of one child a year. The crowded house led to more tension. The two sisters squabbled, spurring the twins to set up two households within a mile of each other on their farm outside Mount Airy. Since they could not go separate ways as ordinary men would, they alternated three days at each home and each conjugal bed—a rigid routine they would follow religiously till their last breath. While the fear of miscegenation between black and white had remained the driving force behind Helper's abolitionist rhetoric, the union between Asian and white, let alone the abnormal kind, would only intensify racial anxiety. In fact, white supremacists like Helper rallied under the banner of abolitionism not with the purpose of saving blacks from the injustice of slavery but with the goal of protecting the purity of the white race from the menace of miscegenation. In this regard, Chang and Eng might have disturbed the racial paradise as imagined by the ilk of Helper not only through their marriage to two white women but also through their possible relations with their slave women.

Now—back to the Bunker reunion in 2003. It was a grand occasion of celebration, a gathering of people who were products of a union unthinkable to most. The Bunker descendants certainly proved how wrongheaded Helper and other nineteenth-century racial apologists were, or how unfounded their crackpot racial theories were. Contrary to the fear of racial contamination and degradation, the Bunker progeny were all respectable citizens. Many of them were highly educated, smart, savvy; some were army generals, presidents of major corporations, and elected government officials. In the midst of this multiracial harmony, however, the appearance of a black woman with a claim on the proud Bunker genealogy wreaked no small havoc. Subsequent steps taken by some of the Bunker descendants indicated how sensitive the matter was, or how unbearably haunting family history can be.

Even before the 2003 reunion, some Bunker descendants, perhaps motivated by the Jefferson/Hemings controversy, had made inquiries in May of 2002 to the staff at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, where the autopsy of Chang and Eng had been conducted in 1874 and where the fused liver of the twins is still preserved. These descendants had asked about "the possibility of testing hair trapped in the plaster of Chang and Eng's body cast to confirm anecdotes about hereditary lineages that issued from their slaves." Although there was no extant record or newspaper report on such a matter during or after the twins' lifetime, these descendants had grown up with family stories about how Patrick Bunker, Eng's son, "used to play with his half-sisters and half-brothers who were enslaved." Now that a descendant of a Bunker slave woman had surfaced, the issue took on added urgency and interest. Gretchen Worden, the curator of the Mütter Museum, who received the inquiry from the Bunker descendants, contacted a forensic scientist at George Washington University about the possibility of "obtaining DNA from either Chang and Eng's hair or liver." The expert replied and affirmed the feasibility of conducting such a test if nuclear DNA was available in the hair root, "if any part of it came away from the follicle when it was pulled away by the plaster."23Wu, Chang and Eng Reconnected, 165–66.

There was, however, no follow-up to this flurry of inquiries. There is no definitive conclusion. Unlike the Jefferson/Hemings situation, in which DNA results brought clarity to a past that many of Jefferson's white descendants had denied for centuries, most Bunker family secrets remain shrouded in the fog of time. However, even without scientific corroboration, family lore still endures, such as the following about the twins:

They attended the local shooting matches, where a turkey or beef was the reward for the best marksman, and Chang and Eng acquired reputations as crackshots with rifles or pistols. It was the object of much curious speculation on the neighbor's part how two men tied together could be so adept, often more adept than a single man.

The farmers in Surry County were frequently plagued by wolves, who wreaked havoc among their livestock. There existed one particularly notorious wolf, christened "Bob-Tail," because he had lost part of his tail in a trap. This wolf did not merely limit his dinings to sheep and cattle, but was believed to have eaten a negro baby who wandered into the woods. Bob-Tail made trouble for three years, and no one was able to trap him, until one night when Chang and Eng were awoken by noises coming from among their livestock. They ran out, taking with them a gun and a slave carrying a lantern. It was Bob-Tail, and the wolf breathed his last at the twins' hands. This coup gave Chang and Eng considerable prestige in the community, especially as no more negro babies were ever known to be stolen or eaten.24Quoted in Wallace and Wallace, The Two, 194–95.

This family vignette, passed down orally through generations, seems to be about the twins' remarkable marksmanship and heroic deed of ridding the community of a dangerous pest. But a more discerning and curious reader, mindful of the genealogical intricacy of a slave-owning household in the antebellum South like that of the twins, might rightly ask, "Negro babies? Whose Negro babies?"

About the Author

Yunte Huang is a poet and professor of English at the University of California–Santa Barbara. Huang is the author of many books and translations, including the bestselling Charlie Chan: The Untold Story of the Honorable Detective and His Rendezvous with American History (W. W. Norton & Co., 2010), which won the Edgar Award and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. His articles have been published in the New York Times, Chicago Tribune, Daily Beast, and others.

Cover Image Attribution:

Eng and Chang Bunker, ca. 1835–1836. Watercolor on ivory by unknown creator. Courtesy of the North Carolina Collection Gallery, Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.Recommended Resources

Text

Aarim-Heriot, Naiji. Chinese Immigrants, African Americans, and Racial Anxiety in the United States, 1848–82. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003.

Joshi, Khyati Y., and Jigna Desai, eds. Asian Americans in Dixie: Race and Migration in the South. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Lee, Robert G. Orientals: Asian Americans in Popular Culture. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1999.

Mohl, Raymond A., John E. Van Sant, and Chizuru Saeki, eds. Far East, Down South: Asians in the American South. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2016.

Orser, Joseph Andrew. The Lives of Chang and Eng: Siam’s Twins in Nineteenth-Century America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Wu, Cynthia. Chang and Eng Reconnected: The Original Siamese Twins in American Culture. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2012.

Web

"Chinese Exclusion Act." Primary Documents in American History, Library of Congress. Accessed March 26, 2018. https://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/chinese.html.

"The Chinese in America—Immigration and Legalized Discrimination 1785–1905." Chinese American Heroes. Accessed March 26, 2018. http://www.chineseamericanheroes.org/history/The%20Chinese%20in%20America%20-%20Immigration%20and%20Legalized%20Discrimination%201785-1905%20v5.pdf.

Eng and Chang Bunker: The Siamese Twins. Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina Libraries (Chapel Hill, North Carolina). Accessed March 26, 2018. http://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/bunkers.

Huang, Yunte. "The Amazing American Story of the Original Siamese Twins." Wall Street Journal. March 31, 2018. www.wsj.com/articles/the-amazing-american-story-of-the-original-siamese-twins-1522334784.

"'Inseparable' Recounts The Unusual Lives Of Conjoined Twins Chang And Eng Bunker." Fresh Air. Podcast. April 2, 2018. https://www.npr.org/2018/04/02/598796873/inseparable-recounts-the-unusual-lives-of-conjoined-twins-chang-and-eng-bunker.

Jones, Jeremy B. "Rekindling Kinship with Family of Chang and Eng Bunker." Our State (Greensboro, North Carolina). October 20, 2017. https://www.ourstate.com/rekindling-kinship-with-family-of-chang-and-eng-bunker/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Cynthia Wu, Chang and Eng Reconnected: The Original Siamese Twins in American Culture (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012), 163–65. |

|---|---|

| 2. | James Hale, letter to Charles Harris, July 27, 1843, North Carolina State Archives. |

| 3. | Herman Melville, Moby-Dick, ed. Harrison Hayford, Hershel Parker, and G. Thomas Tanselle (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press and Newberry Library, 1988), 231. |

| 4. | Martin Crawford, Ashe County's Civil War: Community and Society in the Appalachian South (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001), 2. |

| 5. | Jesse Franklin Graves, "The Siamese Twins as Told by Judge Jesse Franklin Graves," unpublished manuscript, North Carolina State Archives, n.d., 22. |

| 6. | Melvin M. Miles, Eng and Chang: From Siam to Surry (self-published, CreateSpace, 2013), 65. |

| 7. | Evelyn Scales Thompson, Around Surry County (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2005), 14. |

| 8. | Graves, "The Siamese Twins," 23. |

| 9. | Joseph Andrew Orser, The Lives of Chang and Eng: Siam's Twins in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 127. |

| 10. | Greensborough Patriot, October 16, 1852. |

| 11. | Greensborough Patriot, October 30, 1852. |

| 12. | J. E. Johnson, "Siamese Twins," in Mount Airy News, January 3, 1956. |

| 13. | Ibid. |

| 14. | Irving Wallace and Amy Wallace, The Two: A Biography (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1978), 193. |

| 15. | "The Siamese Twins at Home," in Southerner, reprinted in Trumpet and Universalist Magazine, November 2, 1850. |

| 16. | Tiya Miles, The House on Diamond Hill: A Cherokee Plantation Story (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 87. |

| 17. | Hinton Rowan Helper, The Land of Gold: Reality versus Fiction (Baltimore, H. Taylor, 1855), 75. |

| 18. | Robert G. Lee, Orientals: Asian Americans in Popular Culture (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999), 42. |

| 19. | Ibid. |

| 20. | Helper, The Land of Gold, 71. |

| 21. | Ibid., 70. |

| 22. | Ibid., 70, 55–56. |

| 23. | Wu, Chang and Eng Reconnected, 165–66. |

| 24. | Quoted in Wallace and Wallace, The Two, 194–95. |