Overview

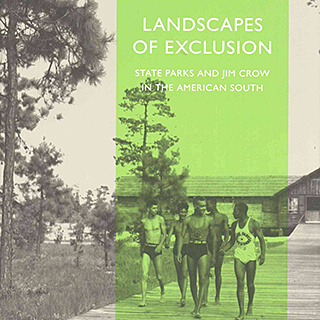

Claudrena N. Harold reviews Sarah Haley's No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016).

Review

There's a gripping scene in Arthur Jafa's award-winning film, Dreams Are Colder Than Death, in which he pairs the image of a small group of African American boys acrobatically diving into a swimming pool with a haunting narration from literary scholar Hortense Spillers. Without equivocation, Spillers warns, "I know that we are going to lose this gift of black culture unless we're careful." Here, she defines "culture" not as a particular art form or creative expression, but as a "special insight that connects us to something human."1Arthur Jafa, Dreams Are Colder Than Death, 2013. Over the course of Jafa's documentary, Spillers, Fred Moten, Kara Walker, and Saidiya Hartman, among others, meditate on the African American condition, the future of blackness, and the fate of the US democratic experiment. Commissioned by the German television station ZDF as part of the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington, Dreams Are Colder Than Death engendered a great deal of conversation among scholars in Black Studies. The buzz centered not just on its stellar cast of intellectuals but also on its formal qualities. Shunning talking heads, Jafa recorded audio and visual components separately and then paired them together during post-production. Such an approach allows for "an extended freedom in both sound and image" where subjects do not produce "survival modalities," defined by Jafa as "the ways that black people have been conditioned to act or appear in film—to sit, stare, or talk in a certain way, or to be assessed by a white gaze."2See Nijla Mumin, "LAFF Review: Arthur Jafa Conducts Multilayered Exploration of Blackness in 'Dreams are Colder than Death,'" Indiewire.com, June 19, 2014, http://www.indiewire.com/2014/06/laff-review-arthur-jafa-conducts-multilayered-exploration-of-blackness-in-dreams-are-colder-than-death-159613/.

Although two years have passed since my first viewing of Jafa's Dreams, Spillers's provocative statements, along with the film's powerful bridging of the lyrical and the sonic, have refused to loosen their grip. The film's formal qualities open up important questions regarding the future of black culture and Black Studies (entering its fifth decade). What are the aesthetic, intellectual, and political challenges confronting scholars in the field? How have the formal qualities of our work advanced? What separates us from other interdisciplinary fields of inquiry and practice?

Jafa's daring formalism whetted my appetite for bold, ambitious scholarship in which "forms, techniques, and ideas coalesce into an indigenous or vernacular tradition while remaining opportunistically open to influence and radical vision."3Marlon Ross, "Introduction" to Houston Baker's speech at the University of Virginia in the spring semester of 2012, https://blackfireuva.com/2012/03/.

Selena Sloan Butler, ca. 1899. Photograph. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in public domain.

Such a work is Sarah Haley's provocative No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity. Haley's meticulously researched, beautifully crafted, and cogently argued first book contributes immensely to US southern, economic, gender, and political history. Examining the experiences of black female convicts in Georgia between emancipation and the 1920s, No Mercy Here enriches our understanding of the importance of African American women—particularly those ensnared in the South's penal system—in the making of New South modernity. It demonstrates the centrality of the carceral regime in the production of gender categories. And it deepens our knowledge of the trajectory and genealogy of black intellectual work around the US prison regime through Haley's highly sophisticated reading of Mary Church Terrell, Selena Sloan Butler, Bessie Smith, and other African American women thinkers and artists. No Mercy Here also breaks new ground in the field of Black Studies through its innovative play with form and structure. Bessie Smith shares theoretical space with Fred Moton, the blues function as not just an explanatory tool but as literary inspiration, and short yet powerful sentences pierce with the intensity of Miles Davis's horn.

The brutality of Georgia's convict system and its central role in the construction of gender categories are the two themes considered early in No Mercy Here. With clarity and imagination, Haley reconstructs the lives of African American women such as Eliza Cobb, who at the age of twenty-two was arrested and convicted for infanticide, a charge she vehemently denied. Legal authorities ignored her declaration of innocence, as well as evidence that her pregnancy was the result of rape. Cobb was first sent to work in a sawmill before being transferred to Milledgeville State Prison. Laboring and living in horrific conditions, Cobb submitted three clemency requests between 1907 and 1910. Suffering from a variety of maladies, including a large growth on the back of her neck, her crippled body could no longer withstand the workload which included tilling the land, planting and harvesting cotton, corn and other crops, cooking and cleaning for other inmates and the employees.

Although African American women rarely received clemency, several white officials intervened on Cobb's behalf. Most notably, the coroner who had testified for the state in her infanticide trial reversed himself, declaring that Cobb had not committed infanticide and that her child had more than likely been stillborn. Guards and administrators submitted letters attesting to Cobb's exemplary behavior at Milledgeville. In 1910, prison administrators included a photograph of Cobb to provide evidence of her physical defects (particularly the large growth on her neck) and to prove "her mind was not as strong as the average negro's." Their framing of Cobb was intentional. "Her description," writes Haley,

as a 'horrible-looking person' may have been attributed to an accident, but it was part of a larger pattern of female representation. Black women's bodies were similarly portrayed in letters from convict guards and overseers as well as in journalistic descriptions and cartoons. Perceived ugliness was one attribute that defined black women's deviance from the category 'woman' and justified their imprisonment and assault during the nadir of American race relations, from the end of Reconstruction through the Progressive era.

Only as an "imbecilic, monstrous body" could Cobb be rendered "legible to white authorities."4 Sarah Haley, No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 19-20. Their strategy of portraying Cobb as monstrous worked, as governor Joseph M. Brown commuted her sentence in September 1910.

Milledgeville and Tattnall Prisons, Georgia State Prison Farm, Milledgeville, Georgia., 1940. Photograph by Lane Brothers Commercial Photographers. Courtesy of Georgia State University Library, Photographic Collection, Special Collections and Archives, Lane Brothers Commercial Photographers Photographic Collection, 1920-1976, digitalcollections.library.gsu.edu/cdm/ref/collection/lane/id/4891.

Equally intriguing is Haley's examination of a clemency petition involving Martha Gault, a white woman charged and convicted in 1923 of assault with the intent to murder. Gault and a male accomplice had stolen a car and brutally beaten the driver, "a deliberate and wanton offense" so grave the judge believed it was "impossible for the human intelligence to entertain any idea of clemency or even leniency after reading the record in this case" (21). Two years into her sentence, Gault petitioned for clemency on the grounds of her transformed character. A victim of her environment, particularly the bad influence of an older man, Gault had been rehabilitated and in the words of prison officials could make "a splendid woman and good citizen" (22). Again, Haley relies on photography to help us understand the racial logics of normative womanhood in the white Georgia imagination. She demonstrates how the presence of white women in Milledgeville destabilized gender categories and created moments of crisis in the state's efforts of racial and gender control.

While the photograph accompanying Eliza Cobb's clemency papers presents her as lacking the "essential traits of personhood and normative femininity," the photograph attached to Martha Gault's papers presents an image of "unassailable femininity."

"Her likeness," Haley notes, "is clear, and her smile is apparent. The partial figure of a companion situated her sentimentality within the realm of feminine friendships and her proximity to a pet reinforced, through distinction, Gault's humanity. Although the photograph was taken at the state farm, the shot makes it difficult to ascertain whether she is inside or outside of the prison, an ambiguity that signaled her fitness for freedom" (22). Fusing the narratives of Gault and Cobb, Haley addresses the racial logic of gender construction, specifically how Cobb's deviant body was required to "make Martha Gault's idealized body real, to give it political, cultural, and social meaning" (23). Here lies one of No Mercy Here's most important interventions: the illumination of carceral institutions as central sites for the making of New South gender identities.

African-American women carry hampers of beans, Georgia's prisons, Georgia, November 3, 1940. Copyright Atlanta-Journal Constitution. Courtesy of Georgia State University Library, Photographic Collection, Special Collections and Archives, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives, digitalcollections.library.gsu.edu/cdm/ref/collection/ajc/id/611/rec/53.

Turning to the brutality of Georgia's penal system, Haley depicts the physical and mental anguish inflicted upon black female convicts and their families. Drawing upon Spillers, Saidiya Hartman, and Angela Davis, she depicts the southern convict camp as a theater of black female abjection, "part of an archipelago of pornotropical sites in which black female bodies were rendered flesh for the production of value: the ideological value of the continued relegation of black people to things and, inextricably, carceral value for southern racial capital through the use of such objects for labor" (87). Rituals of torture against African American women enacted a spectacle of daily violence that haunted black female convicts. Haley also tackles the silence of the archives as representing the "likely belief among black women that they had no claims to femininity that would legitimize assertions of rape" (104). Although prison records provide numerous instances of African American women giving birth to children conceived during their imprisonment, Haley finds no record of a prison guard being investigated for the sexual violation of convicts.

No Mercy Here builds upon and expands insights of convict lease scholars such as Mary Ellen Curtin, David Oshinsky, Talitha LeFlouria, and Alex Lichtenstein. Haley's work also complements that of Khalil Muhammad, Cheryl Hicks, and Kali Gross, who have documented how African American activists and reformers grappled with state-sanctioned punishment in the Progressive Era. Her analysis of the criticisms of convict leasing put forth by Selena Sloan Butler and Mary Church Terrell reminds us that powerful rebuttals of state violence emanated from African American women, who far too often are discussed only in terms of respectability politics and uplift strategies. Haley details how Butler (The Chain-Gang System) condemned the South as an antimodern state formation, rescued African American women from the margins of criminal discourse on punishment, and pushed the National Association of Colored Women to confront the brutalization of black convicts.

Mary Church Terrell, three-quarter length portrait, seated, facing front, ca. 1880–1900. Photograph. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, loc.gov/resource/cph.3b47842.

Equally impressive was the intellectual work of Mary Church Terrell, who in 1907 published "Peonage in the United States: The Convict Lease System and Chain Gangs," one of the most thorough critiques of the system. Anticipating scholars who would treat convict leasing as slavery by another name, Terrell's essay provides a powerful critique of African American female criminalization, positions the chain gang system as a form of debt peonage, and highlights the deep relationship between the carceral regime and economic oppression. Haley also delves into the work of white Progressive Rebecca Latimer Felton. In contrast with Terrell and Sloan, Felton viewed African American women as an inherently and irredeemably deviant group that, like African American men, posed an "all-consuming threat to the white supremacist moral fabric of southern life, including white femininity and womanhood" (151).

No Mercy Here provides a rare portrait of black women's experiences in the parole system, which the Georgia General Assembly established in 1908. Private companies and individuals could conscript recently paroled African Americans to work for at least one year, even if they had served their minimum sentence. Under parole, "black women were forced to labor as domestic workers for white families, giving new meaning to the concept of the prison of the home. They were subject to constant surveillance and the threat of return to the prison camp for any transgression; private individuals, many of whom were now white women, continued to serve as police and warders" (158). This new situation of black women's servitude "differentiated them from men but did not place them closer to normative femininity, since the relation of servant to employer also worked to expose black women's difference from the white women for whom they worked" (176). In this context, Haley discusses how the inclusion of black women on the chain gang, a Progressive penal "reform," also contributed to the codification of women as white. Though the General Assembly stipulated that the chain gangs were for men only, more than two thousand black women were sentenced to this form of hard labor.

Top, Cover to the album compilation Jailhouse Blues featuring artwork by Romare Bearden, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Rosetta Records, 1987. Bottom, Portrait of Bessie Smith, February 3, 1936. Photograph by Carl Van Vechten. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, loc.gov/item/2004663572.

Extending the work of Clyde Woods, Angela Davis, and Ted Gioia, the concluding chapter of No Mercy Here illuminates the blues as an archival source for African Americans' critique of the US carceral regime. "Blues creations," Haley argues, "render an imaginative world of carceral dismantling, not by merely recounting the terror of gendered regimes of imprisonment but by challenging the very foundations of ideologies justifying carceral control" (214). Through music from Bessie Smith, Victoria Spivey, and Herbert Halpert's 1939's Women's A Capella Songs from the Parchman Penitentary5Various artists, Mississippi Department of Archives and History presents Jailhouse Blues: Women's a cappella songs from the Parchman Penitentiary Library Of Congress field recordings, 1936 and 1939. Rosetta Records RR1316, 1987, vinyl., she demonstrates how black women blues artists contested a principal claim of Western liberalism: "the ability to govern through universal tenets of reasonability and the legitimacy of legal actors' decisions and actions" (217). Black women destabilized hegemonic categories of crime and forged codes for living and navigating Jim Crow America. The blues became a vehicle through which "black women protected themselves from negative perceptions by constructing and disseminating a nuanced image of themselves as simultaneously sexual and spiritual, dangerous and vulnerable, heartbroken and strong" (243).

Critiquing the limits of reform discourse, Sarah Haley shows how historical writing can inform as well move us, taking literary risks and imaginative leaps to find meaning in the seeming silences of the archives.

About the Author

Claudrena N. Harold is an associate professor of African American and African Studies and History at the University of Virginia. In 2007, she published her first book, The Rise and Fall of the Garvey Movement in the Urban South, 1918–1942 (New York: Routledge, 2007). In 2013, the University of Virginia Press published The Punitive Turn: New Approaches to Race and Incarceration (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013), a volume Harold coedited with Deborah E. McDowell and Juan Battle. Her latest book is New Negro Politics in the Jim Crow South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2016).

Cover Image Attribution:

African-American women carry hampers of beans, Georgia’s prisons, Georgia, November 3, 1940. Copyright Atlanta-Journal Constitution. Courtesy of Georgia State University Library, Photographic Collection.Recommended Resources

Text

Curtin, Mary Ellen. Black Prisoners and Their World: Alabama, 1865–1900. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2000.

Davis, Angela. Women, Race, & Class. New York: Random House, 1981.

Gross, Kali Nicole. Hannah Mary Tabbs and the Disembodied Torso: A Tale of Race, Sex, and Violence in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Hartman, Saidiya V. Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Hicks, Cheryl D. Talk with You Like a Woman: African American Women, Justice, and Reform in New York, 1890–1935. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

LeFlouria, Talitha L. Chained in Silence: Black Women and Convict Labor in the New South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Lichtenstein, Alex. Twice the Work of Free Labor: The Political Economy of Convict Labor in the New South. New York: Verso, 1996.

Muhammad, Khalil Gibran. The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Oshinsky, David O. Worse than Slavery: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice. New York: Free Press Paperbacks, 1996.

Shapiro, Karin A. A New South Rebellion: The Battle against Convict Labor in the Tennessee Coalfields, 1871-1896. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Web

Boyle, Louise. "America's only female chain gang: The women who pull weeds and bury unclaimed bodies in Arizona desert to avoid 23 hours of lock-down in country's 'toughest jail.'" DailyMail.com, June 29, 2012, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2166260/Americas-female-chain-gang-pictured-pulling-weeds-burying-unclaimed-bodies-100F-Arizona-desert.html.

Browne, Jaron. "Rooted in Slavery: Prison Labor Exploitation." Race, Poverty, & the Environment 14, no. 1 (Spring 2007). Accessed June 6, 2017, http://www.reimaginerpe.org/files/RPE14-1_Browne-s.pdf.

Fraser, Steve and Joshua B. Freeman. "21st century chain gangs: The rebirth of prison labor foretells a disturbing future for America’s ‘free market’ capitalism." Salon, April 19, 2012, http://www.salon.com/2012/04/19/21st_century_chain_gangs.

Haley, Sarah. "'Like I was a Man': Chain Gangs, Gender, and the Domestic Carceral Sphere in Jim Crow Georgia." SIGNS (Autumn 2013): 53–77. Accessed June 6, 2017, http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdfplus/10.1086/670769.

"SLAVERY by Another Name." Public Broadcasting Service, 1995–2017, http://www.pbs.org/tpt/slavery-by-another-name/themes/convict-leasing.

Wilson, Mary Ellen. "The Rise and Fall of Convict Labor in the Central Georgia Lumber Industry." Proceedings and Papers of the Georgia Association of Historians 12 (1991): 146–147. Accessed June 6, 2017, https://archives.columbusstate.edu/gah/1991/146-167.pdf.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Arthur Jafa, Dreams Are Colder Than Death, 2013. |

|---|---|

| 2. | See Nijla Mumin, "LAFF Review: Arthur Jafa Conducts Multilayered Exploration of Blackness in 'Dreams are Colder than Death,'" Indiewire.com, June 19, 2014, http://www.indiewire.com/2014/06/laff-review-arthur-jafa-conducts-multilayered-exploration-of-blackness-in-dreams-are-colder-than-death-159613/. |

| 3. | Marlon Ross, "Introduction" to Houston Baker's speech at the University of Virginia in the spring semester of 2012, https://blackfireuva.com/2012/03/. |

| 4. | Sarah Haley, No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 19-20. |

| 5. | Various artists, Mississippi Department of Archives and History presents Jailhouse Blues: Women's a cappella songs from the Parchman Penitentiary Library Of Congress field recordings, 1936 and 1939. Rosetta Records RR1316, 1987, vinyl. |