Overview

Elliott Bowen examines a venereal disease clinic in Hot Springs, Arkansas, offering insights into class-based, racial, and gendered aspects of the federal government's early twentieth-century public health work.

Public Health in the US and Global South is a collection of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications examining the relationship between public health and specific geographies—both real and imagined—in and across the US and Global South. These essays raise questions about the origin, replication, and entrenchment of health disparities; the ways that race and gender shape and are shaped by health policy; and the inseparable connection between health justice and health advocacy. Selected from a competitive group of submissions, these pieces offer new perspectives on the multiple meanings of health, space, and the public in the US and Global South. The series editor for Public Health in the US and Global South is Mary E. Frederickson.

Introduction

In the winter of 1936, Minnie Lee Ishcomer left home in Idabel, Oklahoma, and journeyed to Hot Springs, Arkansas. Thirty years old, white, poor, and the victim of a long-standing venereal infection, Ishcomer came to Hot Springs hoping to obtain treatment at the VD clinic operated there by the United States Public Health Service (PHS). Her experience was less than satisfactory. Because the clinic officially admitted only acute, infectious VD cases, Ishcomer was initially denied entrance—on the grounds that she was "not a danger to the public health." She passed her first few days in Hot Springs in search of food and shelter. Without money, she made her way to a bus station where a police officer found her "in a very serious condition." Taken back to the clinic, she received a few days' treatment. Soon after her release, a PHS official angrily wired the health officer in Ishcomer's home county that "such cases will not be treated in the future."1H.S. Cumming, Surgeon General, to Charles M. Pearce, State Health Commissioner, Oklahoma, January 29, 1936, General Records of the Venereal Disease Division, 1918–1936, 203.4, in RG 90, Records of the Public Health Service, 1912–1968, National Archives, College Park, Maryland. Hereafter VD Division Records.

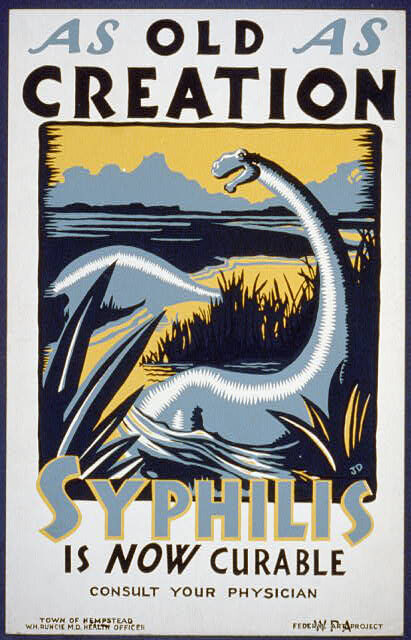

The treatment Minnie Lee Ishcomer received likely did little to improve her health.2Available federal census information indicates that in 1930, Ishcomer was married and had a least one son. Her husband appears to have been a mill hand but no occupation is listed for her. Exactly which of her conditions triggered resentment by clinic doctors is not clear. Nevertheless, her story sheds light on a relatively unexplored site of public health work in the early twentieth-century US South.3For a brief overview of the Hot Springs VD clinic, see Edwina Walls, "Hot Springs Waters and the Treatment of Venereal Diseases: The U.S. Public Health Service Clinic and Camp Garraday," Journal of the Arkansas Medical Society 91, no. 9 (1995): 430–7. The opening of the Hot Springs VD clinic in 1921 followed upon extensive anti-venereal initiatives carried out by the U.S. military during World War I. Closing in the 1940s, the clinic marked a transition in the federal government's campaign against syphilis and gonorrhea—including the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932–72) and the Chicago Syphilis Control Project (1937–40). Throughout the interwar period, Hot Springs sat on the front lines of the PHS's war against VD, and although its efforts were largely unsuccessful, the clinic's history points toward a more complex understanding of this moment of "venereal peril."4The term "venereal peril" was a staple of turn-of-the-century discourse around syphilis and gonorrhea. For a particularly good example of this, see William Leland Holt,The Venereal Peril: A Popular Treatise on the Venereal Diseases, ed. William Josephus Robinson (New York: The Altrurians, 1909). For historical studies on this, see Theodor Rosebury, Microbes and Morals: The Strange Story of Venereal Disease (New York: Viking Press, 1971); Allan Brandt, No Magic Bullet: Venereal Disease and American Society since 1880 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987); Suzanne Poirier, Chicago's War on Syphilis, 1937–40: The Times, the Trib, and the Clap Doctor (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1995); Nancy K. Bristow, Making Men Moral: Social Engineering during the Great War (New York: New York University Press, 1996); Andrea Tone, Devices and Desires: A History of Contraceptives in America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2001); Marilyn Hegarty, Victory Girls, Khaki-Wackies, and Patriotutes: The Regulation of Female Sexuality during World War Two (New York: New York University Press, 2008); John Parascandola, Sex, Sin, and Science: A History of Syphilis in America (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2008).

The history of the Hot Springs clinic offers insights into racial, gendered, and class-based aspects of the federal government's campaign against syphilis and gonorrhea. The clinic treated all manner of patients—black as well as white, male as well as female. Some patients were chronically poor, and others—particularly with the onset of the Great Depression—had only recently fallen on hard times. How similar were the experiences of these different groups, and to what extent did their treatment reflect prejudices against the various "others" (such as prostitutes and African Americans) popularly associated with VD? While many historical VD studies examine population subsets, this article about Hot Springs offers a more comprehensive analysis, comparing the experiences of stigmatized groups along with those of Hot Springs's prototypical health-seekers: syphilitic white males. Although they accounted for the vast majority of the clinic's caseload, white men have not received significant attention in VD historiography. Including their experiences adds new depth to our understanding of the "venereal peril" while illustrating how forcefully eugenics pervaded the PHS's campaigns against syphilis and gonorrhea.

Eugenics, of course, figures prominently in scholarship on the infamous Tuskegee Study. This experiment, in which the PHS deliberately withheld treatment from four hundred syphilitic Alabama black men in order to study the disease's "natural" progression, was designed to provide evidence for the theory that (as the Johns Hopkins syphilologist Joseph Moore put it) "syphilis in the negro is in many respects almost a different disease from syphilis in the white."5Susan Reverby, Examining Tuskegee: The Infamous Syphilis Study and Its Legacy (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 136. From 1932 to 1972 white PHS doctors attempted to prove that black syphilitics almost never progressed to the late, advanced stage of the disease characterized by disorders of the nervous system–including tabes (syphilis of the spinal cord) and paresis (syphilis of the brain). Blacks were seen as belonging to an uncivilized race with smaller, less developed brains that equipped them with a "racial resistance" to neurosyphilis; as a result, they were more likely to suffer from the disease's cardiovascular symptoms—including syphilis of the heart.6Christopher Crenner, "The Tuskegee Syphilis Study and the Scientific Concept of Racial Nervous Resistance," Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 67, no. 2 (2012): 244–80. Doctors believed that this partial immunity to neurosyphilis was a hereditary trait. As the authors of a recent article on Tuskegee observe, the experiment's goal was to "prove the biological basis of racial difference by documenting race-linked pathology, consistent with prevailing eugenic theory."7Paul A. Lombardo and Gregory M. Dorr, "Eugenics, Medical Education, and the Public Health Service: Another Perspective on the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment," Bulletin of the History of Medicine 80, no. 2 (2006): 313.

In providing an assessment of intellectual undercurrents circulating through the PHS in the 1920s and 1930s, this new literature successfully rebuts the claim that Tuskegee had little to do with scientific racism or eugenics.8For a recent article in the revisionist vein, see Thomas G. Benedek and Jonathon Erlen, "The Scientific Environment of the Tuskegee Study of Syphilis, 1920–1960," Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 43, no. 1 (1999): 1–30. Unanswered, however, is how eugenic theories informed aspects of the agency's anti-venereal work involving non-blacks. At Hot Springs, these theories found expression in a campaign designed to prevent the clinic's mostly white male patients from succumbing to the "racial poison" that was VD. Comprising traditional medical services and a variety of extra-medical measures (including financial assistance for food, shelter, and basic care), this campaign cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, with its budget increasing dramatically during the early years of the Great Depression—just as the PHS dismantled a number of pilot projects designed to provide mass treatment to syphilitic blacks. Although many of the initiatives undertaken in Hot Springs benefited patients regardless of race or sex, the clinic's white male health-seekers experienced a level of preferential treatment denied to both women and African Americans. Further, for the latter group, discrimination and hostility were part and parcel of the Hot Springs experience—both inside and outside the clinic. All of this represented the eugenic impulses coursing through the PHS facility, whose director—Oliver C. Wenger—declared syphilis and gonorrhea important "from the standpoint of race conservation."9O.C. Wenger, "The Need for Social Hygiene," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives.

Hot Springs reveals a significant instance of the federal government's racist approach to public health policy. When dealing with white patients, Washington extended a taxpayer-supported hand. Because such a sizable gap existed between the experiences of Hot Springs's black and white health-seekers, the story of the city's VD clinic provides a further context for understanding the Tuskegee Study. But first, a more elementary question: why did the PHS decide to create a VD clinic at Hot Springs, Arkansas?

"Mecca for Syphilitics"

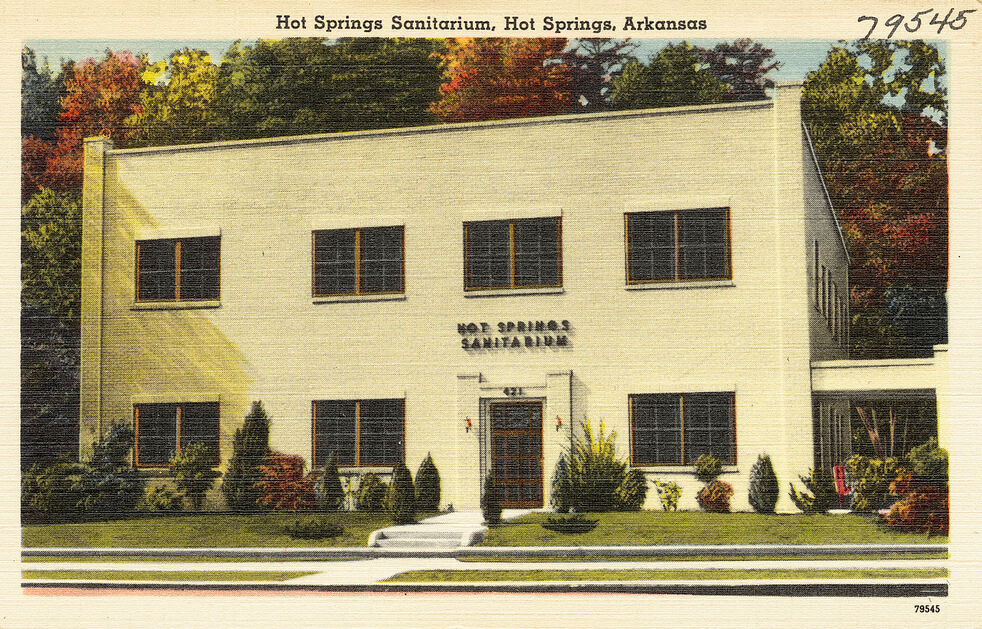

Hot Springs's selection as the site of the federal government's "model" VD clinic would not have surprised early twentieth-century Americans.10C.N. Myers, "Hot Springs and the Model Federal Venereal Disease Clinic," Medical Review of Reviews 28 (1922): 86. In 1832, Congress declared that the boiling waters of the Ouachita Mountains were to be forever set aside for the "benefit and enjoyment" of the general public.11For more on the city's early history and the role of the Hot Springs Reservation, see Janis Kent Percefull, Ouachita Springs Region: A Curiosity of Nature (Hot Springs, AR: Ouachita Springs Region Historical Research Center, 2007). In 1877, Congress created the Hot Springs Reservation (HSR). Initially consisting of 2,529 acres, the HSR was public land managed by a federally-appointed commission, whose task was to maintain and control access to the 826,000 gallons of water that daily coursed through the site.12J.K. Haywood, Analyses of the Waters of the Hot Springs of Arkansas (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1912), 5. Word of the area's therapeutic prowess spread across the country, and as the city began welcoming hundreds of health-seekers every year, its waters acquired a reputation for curing syphilis.13For evidence of this, see A.J. Wright, "Some Account of the Hot Springs of Arkansas," The New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal (1860): 798–9, 801; R.M. Lackey, "The Hot Springs of Arkansas," Chicago Medical Journal 23 (1866): 9; J.L. White, "The Hot Springs of Arkansas," Chicago Medical Recorder 36 (1878): 311. During the late nineteenth-century, a growing belief in the springs' ability to "drive out syphilis completely" spurred a "Hot Springs craze" among venereal sufferers. Contemporaries began referring to the city as the "Mecca for syphilitics in America."14S.B. Houts, "Cases in Practice," The Medical World 5 (1887): 248–52; Edward L. Keyes, The Venereal Diseases, Including Stricture of the Male Urethra (New York: William Wood & Company, 1880), 107–8; E.R. Lewis, "The Hot Springs of Arkansas," The Kansas City Medical Index-Lancet 10, no. 7 (1889): 249. For references to Hot Springs as a "Mecca" for syphilitics during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, see "Editorial: Syphilis of the Nervous System," The Hot Springs Medical Journal 3, no. 2 (1894): 51; A. Ravogli, "The Thermomineral Cure in the Treatment of Syphilis," The Medical Era 6, no. 8 (1897): 276; Bukk G. Carleton, A Treatise on Urological and Venereal Diseases (New York: Bukk G. Carleton, 1905), 741; Loyd Thompson, Syphilis (Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Febiger, 1920), 212.

While some of Hot Springs's health-seekers received treatment at the Free Government Bathhouse created by the HSR in 1878, increasing numbers did so at private enterprises.15Haywood, Analyses of the Waters, 5. Hot Springs was "fast becoming a fashionable resort."16J.L. Gebhart, "On the Therapy of the Waters of Hot Springs, Arkansas, and Their Relation to the Medical Profession at Large," St. Louis Medical and Surgical Journal 38 (1880): 634. Leasing land and water from the HSR, local developers began replacing the city's "miserable board shanties" with "palatial hotels."17Robert Heriot, "Letter to the Editor," Locomotive Engineers Journal 25 (1891): 919. The resort's clientele shifted: earlier the preserve of "poor, miserable paupers," it was increasingly visited by "very wealthy people from the Northern states."18E.B. Stevens, "Hot Springs, Arkansas," Transactions of the Ohio Medical Society 31 (1875): 197; Heriot, "Letter to the Editor," 919. See also H.M. Rector, "Then and Now," Hot Springs Medical Journal 4 (1895): 225; Henry Durand, "Uncle Sam, M.D., and His Great Sanitarium," The American Monthly Review of Reviews 16 (1897): 75–9. To ensure that its visitors remained a "people of leisure, with an abundance of money to spend," local officials forcibly uprooted the city's poorer health-seekers—those living in "shanties or tents" or found "encamped under the trees with no other shelter."19"Hot Springs, Arkansas," The Medical Visitor 20 (1904): 140; "Hot Springs, Arkansas, as a Health Resort," Hot Springs Medical Journal 3, no. 6 (1894): 173; William H. Deaderick, "The Development of the Hot Springs of Arkansas as a Health Resort," The Medical Pickwick 2 (1916): 265–6. One turn-of-the-century visitor reported on how "it was the policy of the municipality of Hot Springs to discourage the coming of the poor people to that place," which it did "by withholding all of the usual eleemosynary institutions from their use." Hal C. Wyman, "A Surgical Pilgrimage to Arkansas," Physician and Surgeon 28 (1906): 207. Medical authorities in other locales came to believe that "only the rich" could afford the "costly excursion" to Hot Springs.20"Syphilitic Paresis," The Eclectic Medical Journal 50 (1890): 562. As a Chicago physician said of his city's syphilitic patients: "our rich people go to the great Mecca of medical wisdom, to Hot Springs," while "our poor people may go to—where they please."21Joseph Zeisler, "The Social Evil," Year Book (Chicago: The Sunset Club, 1894), 218.

The invention of Salvarsan (1910), a more effective drug, also prompted a decline in the city's voluminous traffic in syphilitic health-seekers.22"Since the arsphenamines have justly become popular," the director of the Hot Springs VD clinic observed in 1921, "the number of syphilitics coming to Hot Springs has been decreased year by year." O.C. Wenger, "The Early Days of Hot Springs, Arkansas (1850–1900)," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives. Nevertheless, neither new drugs nor the discrimination against impoverished health-seekers succeeded in severing the city's association with VD.23"We see every day, here in Hot Springs," one local physician noted in a 1913 treatise, "from ten to a hundred persons" suffering from the "terrible disease" that was syphilis. Albert J. Whitworth and John M. Byrd, The Hot Springs Specialist (Memphis, TN: B.C. Toof & Company, 1913), 164. For more about Salvarsan, see Patricia Spain Ward, "The American Reception of Salvarsan," Journal of the History of Medicine & Allied Sciences 36, no. 1 (1981): 44–62. In 1920, the HSR created a new, expanded Free Government Bathhouse; its lower floor would soon become home to the PHS's VD clinic.24Oliver C. Wenger, "The Early Days in Hot Springs, Arkansas (1850–1900)." Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives. As its director put it upon entering the city that same year: "to the average layman, Hot Springs, Arkansas, means VD, and VD means Hot Springs."25Oliver C. Wenger, "Results of a Study and Investigation of Venereal Disease at the United States Public Health Service Clinic at Hot Springs, Arkansas," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives.

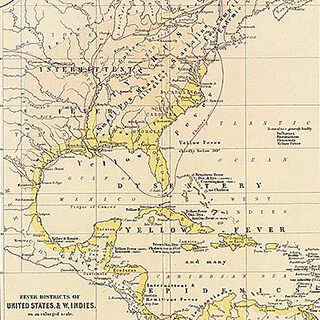

Hot Springs's status as federal land and as a "mecca" for syphilitics made the city an ideal site for the PHS's "model" VD clinic. But why would the government create such a clinic? The early twentieth-century was a time of profound anxiety over syphilis and gonorrhea, diseases said to be "undoubtedly on the increase."26George P. Dale, "Moral Prophylaxis," The American Journal of Nursing 11, no. 9 (1911): 689. It is unknown whether the general prevalence of VD increased during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. What changed was likely not the percentage of the population infected by syphilis or gonorrhea, but instead, the medical profession's awareness of how many illnesses originated in one of these two diseases. Medical authorities proclaimed that 80 percent of adult males living in large cities contracted syphilis or gonorrhea before the age of thirty, and that 80 percent of all operations performed on women for diseases of the womb and ovaries were the result of one of these conditions. Such figures, though highly suspect, engendered fears of a looming VD epidemic across the country.27For these estimates, see G. Shearman Peterkin, "A System of Venereal Prophylaxis That is Producing Results," American Medicine 10 (1906): 328. A colleague named John Cunningham declared that "it is a fact worthy of consideration that every year in this country 770,000 males reach the age of maturity. It may be affirmed that under existing conditions at least 60 percent, or over 450,000 of these young men will sometime during life become infected with venereal disease, if the experience of the past is to be accepted as a criterion of the future." John C. Cunningham, "The Importance of Venereal Disease," The New England Journal of Medicine 168, no. 3 (1913): 77–8.

The sense that venereal diseases constituted "a menace to the national welfare" stemmed less from epidemiology than from social and cultural concerns—of "race suicide" attendant upon the declining fertility of native, white-born women and the influx of "new immigrants," of urbanization and its impact on sexual mores, of a "family crisis" prompted by the emergence of the "new woman," and of eugenic concerns tied to the rhetoric of social Darwinism and racial degeneration.28Abraham L. Wolbarst, "The Venereal Diseases: A Menace to the National Welfare," Medical Review 62 (1913): 327–80. Reformers clamored for an attack on prostitution, artists luridly illustrated the consequences of untreated syphilitic and gonorrheal infections, and anxious legislators passed laws that ranged from the reporting of all professionally-handled VD cases to the bacteriological examination of immigrants and prospective spouses.29For more on this, see Brandt, No Magic Bullet.

The climax of these fears came during World War I. With scientific diagnoses, doctors found that a surprisingly high number of prospective US military recruits suffered from VD. Hoping to head off a manpower shortage, in 1917 Congress created the Committee on Training Camp Activities—an organization that sought to curb the venereal scourge through the forced incarceration of prostitutes, the provision of medical services for infected soldiers, and the establishment of "wholesome" alternatives to the vice-ridden recreational opportunities commonly found in cantonment zones.30See Bristow, Making Men Moral. See also Alexandra M. Lord, "Models of Masculinity: Sex Education, the United States Public Health Service, and the YMCA, 1919–24," Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 58, no. 2 (2003): 123–52. The following year Congress passed the Chamberlain-Kahn Act, which created the PHS's Division of Venereal Diseases and allocated two million dollars for the establishment of free VD clinics across the country.31For the Chamberlain-Kahn Act, see Alexandra M. Lord, "'Naturally Clean and Wholesome': Women, Sex Education, and the United States Public Health Service, 1918–1928," Social History of Medicine 17, no. 3 (2004): 423–41. As the war came to a close, Washington followed up on these efforts by conducting a nationwide VD survey.

Each of these actions drew attention to Hot Springs. Throughout the war, military authorities fretted over Little Rock's Camp Pike, a training facility whose VD rates were reportedly "the [highest] by far of any camp or cantonment in the United States."32Victor C. Vaughan, "Protection of American Army Against Social Diseases by More Rigid Health Laws," The Pennsylvania Medical Journal 22 (1918): 26. According to Vaughan, the venereal disease rate at Camp Pike was 568.7 per 1,000 soldiers. See also, "Disease Conditions among Troops in the United States: Extracts from Telegraphic Reports Received in the Office of the Surgeon-General for the Week Ending October 19, 1917," Journal of the American Medical Association 69 (1917): 1535–6; "Venereal Disease and Birth Control," Journal of the Switchmen's Union 20 (1918): 756. According to local commanders, Camp Pike's reputation as a hotbed of sexual sickness owed to its proximity to Hot Springs, where prostitution had been legal since the late nineteenth-century and where brothels enjoyed a reputation as home to the profession's "aristocrats."33For evidence of this, see the letters of Archie C. Cowles, a syphilitic health-seeker who traveled to Hot Springs in 1905. In a letter dated December 10, 1905, Cowles wrote that "many of the women here seem to be on the courtesan order. Of course, it would not do to call them prostitutes," Cowles remarked, "for they are aristocrats in their profession." For Cowles' correspondence, see the Archie C. Cowles Papers, Garland County Historical Society Archives, Hot Springs, Arkansas. In August 1918, Camp Pike's commanders ordered the closure of Hot Springs's numerous "houses of immorality."34"Commissioners Issue Order to the City Manager to Close the Houses of Immorality, Which Goes into Effect at Once," Hot Springs Sentinel-Record, August 2, 1918. Local businessmen and religious leaders rejected the association the military made between Camp Pike's high venereal disease rate and the "terrible conditions" in Hot Springs. See "Ministerial Men to Discuss Morals: Report from Washington of Bad Conditions Here Stirs some Enthusiasts," Hot Springs Sentinel-Record, August 9, 1918; "The Moral Condition," Hot Springs Sentinel-Record, August 10, 1918. Municipal authorities reluctantly complied, but the federal government's interest in Hot Springs did not end. While conducting their post-war VD survey, government officials grew increasingly anxious about the city's "serious medical and social problems," observing that Hot Springs was home to an increasing population of venereally afflicted "indigents" and an entirely "inadequate" public health infrastructure.35Audrey Wenger McCully, "The United States Public Health Service Venereal Disease Clinic and Government Free Bathhouse, 1919–1936," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives.

From the federal perspective, syphilitic health-seekers represented an "interstate menace."36"Proceedings of the Minnesota Academy of Medicine," Minnesota Medicine 5 (1922): 61. The PHS determined to "protect the rest of the country" from those who traversed it with a venereal infection.37First Deficiency Appropriation Bill, 1921; Hearings before Subcommittee of House Committee on Appropriations, 66th Congress, 3rd Session (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1921), 588. Opening a clinic in Hot Springs devoted to rendering the afflicted non-infectious seemed the best means of accomplishing this goal. Because patients traveled here from all parts of the country, constituted a diverse racial and socioeconomic makeup, and encompassed the full range of syphilitic infections, the PHS also found in Hot Springs an unprecedented opportunity for research. Establishing a long-term presence here would also allow the government to continue its wartime campaign against "houses of immorality," while transforming a parochial medical culture.38This last point holds for all of the public health campaigns undertaken in the early twentieth-century US South. In the case of Hot Springs, the city was seen as a center of quackery, and in particular, of the country's VD patent medicine industry. See Excluding Advertisements of Cures for Venereal Diseases from the Mails; Hearings before the Committee on the Post Office and Post Roads of the House of Representatives, 66th Congress, 1st Session (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1921).

In late 1920 the PHS drew up plans for the facility, obtained $300,000 in construction funds and selected Oliver C. Wenger, one of the country's leading venereologists, as director.39During the war, Wenger—a native of St. Louis—served in the Medical Corps of the Missouri National Guard, and later focused his efforts on "venereal disease prophylaxis" as a member of Sanitary Squad #18, stationed in Camp Mills, a military camp in Long Island, New York. Afterwards, Wenger sought and obtained appointment as a "regional consultant" in the PHS, whereupon he assisted in the nationwide venereal disease survey (1919–20). See McCully, "The United States Public Health Service." Born in St. Louis in 1884, Wenger obtained his MD from St. Louis University in 1908. During the First World War, he served in the Medical Corps of the Missouri National Guard, later traveling to England and France as part of a sanitary squad involved in VD control.40For more on Wenger's biography, see McCully, "The United States Public Health Service." His time in Europe convinced Wenger to devote all his efforts to venereology. According to a contemporary, Wenger's idea of heaven was a place containing "unlimited syphilis," and of course, "unlimited facilities to treat it."41Reverby, Examining Tuskegee, 141. In 1919, Wenger joined the PHS Division of Venereal Disease. Before becoming director at Hot Springs, his first assignment was the national VD survey.

Inside the Clinic

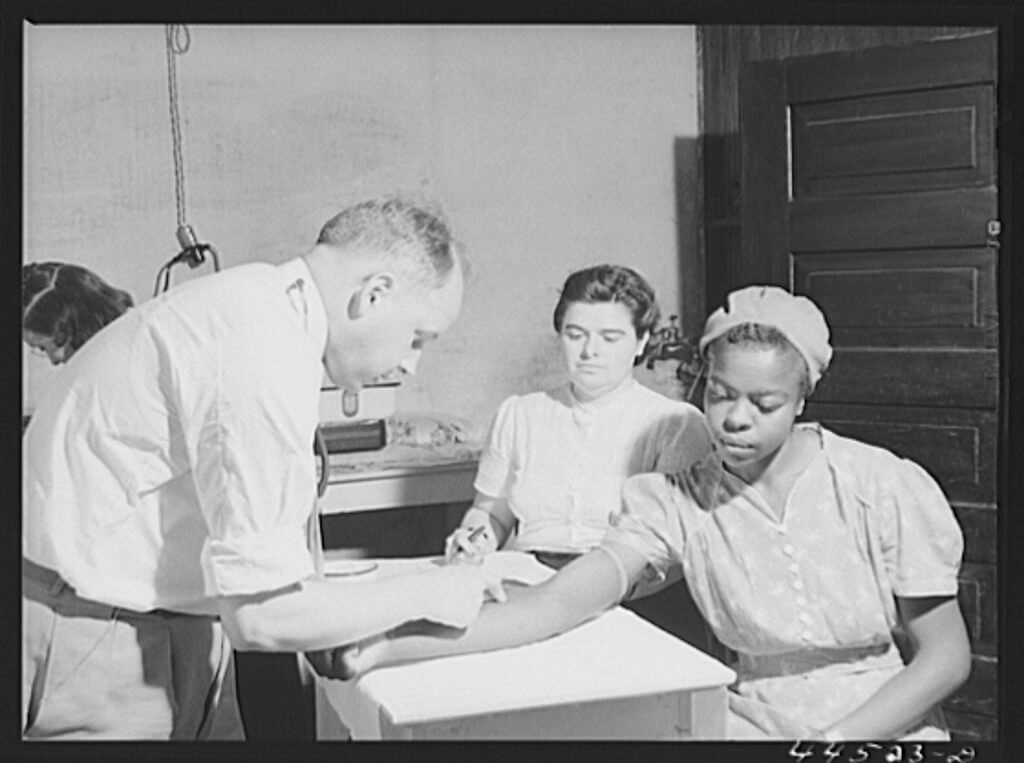

With an inaugural budget of $40,000, the clinic opened in August 1921.42Oliver C. Wenger to C.C. Pierce, March 16, 1921, Hot Springs National Park Administrative Archives, Subseries 25.1.4, File A7615[04]. Hereafter NPS Archives. In its first year, five hundred patients received treatment; a total of 61,930 patients—male and female, black and white—had wound their way through by 1936, receiving 1.2 million injections of mercury and Salvarsan. Who were these individuals? How did their circumstances, needs, and experiences differ? How did prevailing ideas about VD actions influence Hot Springs's response to syphilis? And how did the clinic's campaign develop over the course of the 1920s and 1930s?

On one level, the PHS's day-to-day work reflected the widespread belief that VD constituted the "wages of sin"—a sign of sexual immorality. In lectures given by clinic personnel, patients learned that their illnesses were the result of "ignorance and your own misconduct." This message of personal irresponsibility also extended to the clinic's official instructions, which warned patients not to "loaf downtown" between treatments. Above all other commandments stood one: "DON'T GET INTO TROUBLE." And because the minimum course of therapy lasted between twenty and thirty weeks, patients were "expected to make arrangements to pay [their] own room and board."43Oliver Wenger, "Instructions" (1921), Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives.

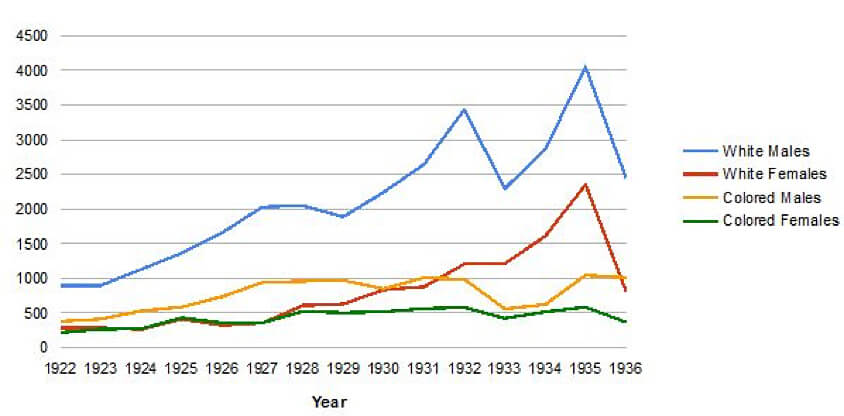

Figure 1: VD Cases Admitted to the Hot Springs Clinic, 1922–1936

The PHS advised that "no patient should go to Hot Springs without at least a return ticket and $100 in cash." Such expectations clashed with reality. Wenger observed that "less than five percent of these indigent persons had funds with which to maintain themselves while receiving free treatment."44McCully, "The United States Public Health Service." Many arrived "without one cent of money."45O.C. Wenger, "The United States Public Health Service Clinic at Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives. In 1931, the average applicant carried not "$100 in cash" but $15.43. The following year, $8.76.46Oliver C. Wenger, "A Comparative Study of the Amount of Money Each Applicant Declared Under Oath at the U.S. Government Bath House for the Years 1931–32," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives. Resembling a "dumping ground of many indigents" during the 1920s and 30s, Hot Springs became the preserve of all sorts of "unfortunate people" who "slept out on the hillside or in alleys, begging food from door to door...or looking for food in garbage cans."47 O.C. Wenger, "United States Conducts Clinics for Venereal Diseases," Nation's Health 8 (1926): 103; McCully, "The United States Public Health Service." As the clinic's director admitted, "the great majority left…before they could receive enough treatment to give them any real benefit."48McCully, "The United States Public Health Service."

One of this "great majority" was Virgil Oren Adams. A native of Clovis, New Mexico, during the early 1930s Adams made several visits to the Hot Springs VD clinic. Each time, he "ran out of funds" after only a few weeks, and being "sick and weak from lack of food and sleep," was forced to leave. In 1934 he wrote to President Roosevelt seeking assistance for yet another clinic trip. "I have been fighting syphilis since 1927," Adams wrote, adding that he was "very much interested in…getting rid of this terrible disease." "[A]bsolutely broke," Adams entreated Roosevelt for a letter to take "as a recommendation for treatments at Hot Springs." "Anything you can do in my behalf," he pleaded, would be "highly appreciated."49Virgil Oren Adams to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, September 27, 1934. Part of Adams's story also derives from a letter he sent to Captain Geoffrey, an officer at the Hot Springs clinic. For full texts, see VD Division Records.

Cases like Adams's were of "daily occurrence."50Oliver C. Wenger to the Surgeon General, October 18, 1934, VD Division Records. While poverty hampered patients' chances of recovery, so did the advanced state of their ailments. Most venereal sufferers came to Hot Springs long after contracting syphilis or gonorrhea. Most had not received more than a few shots of mercury or Salvarsan, and many relied only on cheap, ineffective patent medicines.51For evidence of this, consider the case of James Gordon. A Michigan man, in 1926 Gordon wrote the PHS asking for help in getting to Hot Springs. "I have tried [sic] all kinds of medicines, which you know that it [sic] takes money." From a book he had read, Gordon surmised that "there is not mutch [sic] chance for a poor man there," but still he pleaded: Hot Springs was "the last chance I have got—I have every thing [sic] else until my money is gone." For this letter, see James R. Gordon to United States Public Health Service, August 17, 1926, VD Division Records. Their illnesses were chronic, and generally immune to existing remedies. With disease burrowed deep in their bodies, few had any hope of ever being free from VD.

Realities such as these inspired a modicum of sympathy among clinic doctors. Particularly worrying to Wenger was the fate of ex-servicemen. Disappointed by the fact that during World War I, "our young American manhood" was often "unable to serve because of venereal diseases," Wenger observed hundreds of infected former soldiers seeking admittance to the Hot Springs clinic during the early 1920s. Like most patients, they were "nomads, seeking treatment here and there." Particularly troubling was the fact that these veterans were beginning to form families, and had entered "the best years [of their lives] from an economic standpoint." All of them needed medical attention; none were in a position to pay. Such matters made the treatment and control of syphilis and gonorrhea a national priority, he urged, especially "from the standpoint of race conservation."52Wenger, "The Need for Social Hygiene."

Language such as this dovetailed with contemporary eugenic discourse. Like other eugenicists, Wenger's interest in "race conservation" stemmed from anxieties over white racial purity and integrity. Over the course of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, birth rates among native-born white women declined by approximately 45 percent, and this, coupled with the simultaneous arrival of millions of "new immigrants" from southern and eastern Europe, prompted fears of "race suicide" among the nation's political and cultural elite.53For more on America's fertility transition, see J. David Hacker, "Rethinking the 'Early' Decline of Marital Fertility in the United States," Demography 40, no. 4 (2003): 605–20. Speaking to these fears, New York City gynecologist Abraham Wolbarst opined that "the flower of our land, the mothers of our future citizenship, are being mutilated and unsexed by surgical life-saving diseases, particularly gonorrhea."54Wolbarst, "The Venereal Diseases," 373. Sentiments such as Wolbarst's were widely held by PHS officials, including Oliver Wenger—whose eugenic beliefs scholars have also observed in his later work in Tuskegee and Chicago.55For more on this, see Reverby, Examining Tuskegee, 139–44.

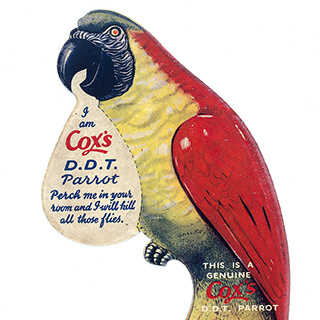

The PHS sought means of accelerating the therapeutic process. Among the myriad venereological experiments conducted at Hot Springs, none loomed larger than those undertaken within the Salvarsan room. During the early 1920s clinic personnel began "the intensive and continuous plan of treatment."56McCully, "The United States Public Health Service." In the typical VD clinic, patients received one dose of Salvarsan per week; in Hot Springs, they would receive twice that amount.57J.R. Waugh and Elizabeth Milovich, "Severe Reactions to Arsphenamine among 3,050 Previously Untreated Patients," Journal of Venereal Disease Information 21, no. 12 (1940): 391. The Hot Springs clinic, it bears noting, was far from the only site where this experimental use of Salvarsan took place. In the medical literature of the time, many physicians reported success with an accelerated treatment regimen, and some recommended giving as many as three doses in a twenty-four hour period. One advocate advised colleagues to "give the largest possible amount of salvarsan in the shortest possible time." Faxton E. Gardner, "The Treatment of Syphilis," Medical Times 45 (1917): 63. For more discussions of the intensive and continuous treatment of syphilis with Salvarsan, see Frederick W. Smith, "The Modern Diagnosis and Treatment of Syphilis," Medical Record 91 (1919): 186–91; B.C. Corbus, "Prophylaxis in Cerebrospinal Syphilis," Journal of the American Medical Association 69, no. 25 (1917): 2087–9; Carlyle N. Haines, "Salvarsan in Syphilis," Pennsylvania Medical Journal 24 (1921): 839–41.

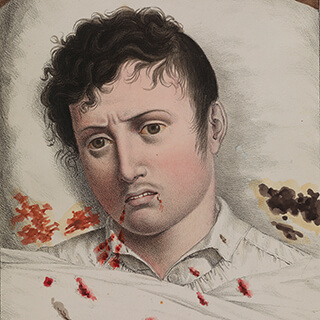

Derived largely from arsenic, a highly toxic substance, Salvarsan was a frightening remedy. While more effective than mercury, its use was accompanied by a panoply of side effects—from the mild (dermatitis, gastro-intestinal distress) to the severe (ocular damage, cardiac distress, edema). In rare cases, death resulted. In a review of 6,308 syphilis patients admitted between 1922 and 1932, Wenger counted a total of 225 adverse reactions to Salvarsan—including three fatalities from arsenical poisoning.58O.C. Wenger and Lida J. Usilton, "Notes on the Syphilis Clinic, United States Public Health Service, Hot Springs, Arkansas," Journal of Venereal Disease Information 15, no. 6 (1934): 210. It is impossible to verify these morbidity and mortality figures, as the clinic operated free from federal oversight. Because of this, and also because of the clinic's generally poor record-keeping practices, the number of "adverse reactions" may be higher than what Wenger reported. For more on the latter problem, see C.H. Waring to the Surgeon General, January 23, 1923, VD Division Records. It appears that severe reactions to Salvarsan were more common here than elsewhere.59In a 1940 study, clinic personnel revealed that nearly 2.5 patients per thousand experienced "severe reactions" to Salvarsan—a rate higher than the 1.99 per thousand reported by the Cooperative Clinical Group's studies of syphilis. Waugh and Milosivic, "Severe Reactions." Cognizant of the fact that "the duration of anti-syphilitic treatment at the Hot Springs clinic is for a relatively short time," Wenger's staff rushed to experiment with untested modes of therapy. The adoption of an "intensive and continuous plan of treatment" contributed to the clinic's high rate of serious complications.60Wenger and Usilton, "Notes on the Syphilis Clinic," 209. For further evidence of serious medical complications following upon the clinic's intensive plan of syphilis treatment, see George E. Tarkington, "Value of Liver Function Test in Arsenical Therapy," Journal of Venereal Disease Information 7, no. 1 (1926): 24–5. For details of a specific injury, see Paul S. Carley, "Infarction of Buttock from Intra-Muscular Injections of Mercury Benzoate," Journal of Venereal Disease Information 17, no. 10 (1936): 281–3. It bears noting here that during the 1920s and 1930s, the idea of "informed consent" had not become a universally recognized principle within medical ethics. Because of this, scientific investigators were not required to obtain patient permission before proceeding with experiments. Those housed within custodial institutions (public hospitals and clinics, asylums, prisons, orphanages, etc.) were especially targeted for human subjects research, with the justification often being that they owed society a debt in exchange for the free treatment they received. For more on this, see Susan Lederer, Subjected to Science: Human Experimentation in America before the Second World War (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997).

Such was certainly the case for Forrest LaPrade. A twenty-four-year-old Texan who arrived in Hot Springs in March 1930, LaPrade's original intention was to "boil out nicotine and malaria" through the city's "healing waters." Directed to Wenger's clinic for a physical, LaPrade was found to be syphilitic. Over the next few weeks he received seven shots of Salvarsan and eleven of mercury. His condition then worsened.61For the details of LaPrade's case, see G.L. Collins to the Surgeon General, October 11, 1932, VD Division Records.

On May 2, 1930, LaPrade complained of a "slight oedma" of the face, which his physician noted was "characteristic of arsenical poisoning." By the next day, he displayed a "face intensely swollen," along with a fever and an accelerated heart rate. After being diagnosed with erysipelas, LaPrade was transferred by a friend to a nearby hospital, where for twenty-eight days he experienced "untold agonies." Hoping to heal his swollen face, from which dripped "large drops of yellow corruption," LaPrade's doctors covered him with a white, glue-like paste, a remedy that produced a constant itching sensation that left the Texan "at the point of death." "I was actually skinned alive," LaPrade later said, describing how the itching left him "scaled like a fish." Unable to sleep, LaPrade's condition was so bad that his body "trembled like a leaf and even shook or quivered the bed." "I suffered, cried, and prayed as one who was in the doorway of Hell," he recalled with horror. "But for the Lord, I would have been six feet of earth."62Forrest D. LaPrade to Mr. Wright Patman, June 10, 1930, VD Division Records.

Although few patients faced an ordeal like Forrest LaPrade's, the clinic's experiments failed to produce "new and better methods to fight venereal diseases."63M.J. White, "Next Steps in the Field of VD Control from the Standpoint of the United States Public Health Service," Journal of Venereal Disease Information 7, no. 1 (1926): 173. A report from the PHS's Division of Venereal Diseases spoke in disappointed terms: "It was hoped that this clinic would prove useful from a research standpoint, but because of the transient character of the patients, results thus far have not been up to expectations."64"Meeting of the Advisory Committee to the Division of Venereal Diseases, United States Public Health Service, May 16, 1927," Journal of Venereal Disease Information 8, no. 8 (1927): 303. And as late as 1936, clinic personnel were still reporting on the "comparatively small number of treatments given" to patients—a reference to how few individuals completed a full course of anti-venereal treatment.

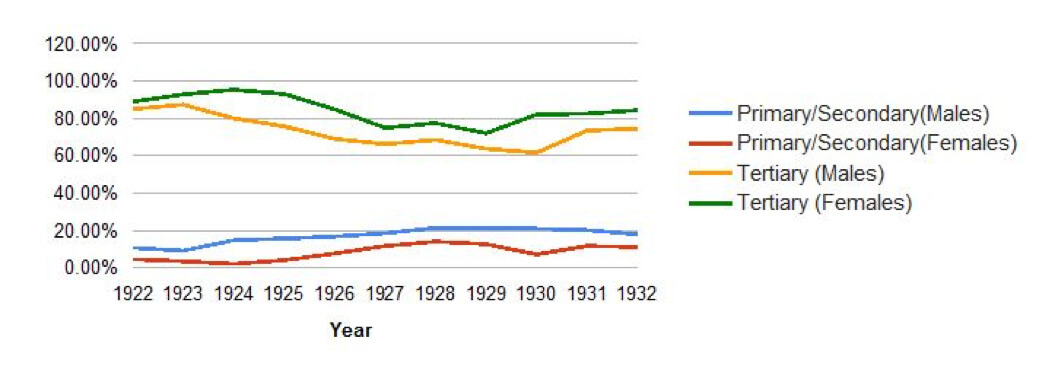

Figure 2: Sex Differentials in Syphilis by Stage of Disease upon Arrival in Hot Springs, 1922–1932

Healing the "Other": Women and African Americans at the Hot Springs VD Clinic

Because their attempts to accelerate the curative process largely failed, Wenger's staff also investigated ways of keeping patients within Hot Springs for longer periods of time. This search for extra-medical means of disease control had a racial foundation, one that becomes clear through an examination of doctors' experiences with female patients. Initially, Wenger and his staff harbored quite negative attitudes toward women, who were seen as "uncontrolled spreaders of infection" and a "menace to the community at large."65Wenger, "The Need for Social Hygiene"; Oliver C. Wenger, Annual Report for 1923, Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives. With the passage of time, however, clinic personnel became increasingly sympathetic to the plight of female health-seekers—even those who supported themselves through prostitution while receiving treatment. From these sentiments (which extended only to whites) emerged a non-traditional disease control program, one rooted not only in testing and treatment, but also in socioeconomic measures—including financial aid for food and housing.

Wenger's first few years in Hot Springs were characterized by an intensive crackdown on the city's red-light districts, which had re-opened in the aftermath of World War I. Hoping to prevent local brothels from recovering their former strength, in January 1921 the PHS presented an ultimatum to municipal authorities, explaining that unless the city abolished its regulated district the agency would quarantine all individuals who came to Hot Springs seeking treatment for disease—venereal or otherwise. Recognizing that it would "prove a great financial blow to the city if this patronage were lost," the PHS argued that it was "absolutely inconsistent to permit men to go there for the cure and, at the same time be exposed to reinfection through the agency of an open red-light district." Women too would be subject to these measures, as some of the female patients in Hot Springs were prostitutes who "carry on their profession while under treatment."66"Hot Springs Threatened With Loss of Patronage: Health Resort Must Eliminate Red-light District," The Social Hygiene Bulletin 8, no. 1 (1921): 8.

This seemed clear from a report Wenger received from the Interdepartmental Social Hygiene Department (ISHD) in 1922. A governmental entity tasked with investigating the relationship between prostitution and VD, the ISHD in 1921 sent an agent named Blanche Young to Hot Springs. Upon questioning a few girls "of the prostitute type" found within the city's public dance halls, she concluded that no progress against VD would be forthcoming unless the federal government abolished its system of regulated prostitution. One of the prostitutes Young met with informed her that "she had gone to the city for medical treatment and was under the care of a private physician." On another occasion, Young encountered a "very fast looking girl enter[ing] an automobile occupied by three young men who were obviously under the influence of liquor." "A little later," Young continued,

I saw this automobile stop and the men 'pick up' two girls. This was about 11:43 PM. The men talked to the girls on the street, inducing them to enter the car, immediately driving off. The next day I recognized in both the G.U. [genito-urinary] and syphilis clinics one of the girls who was present in the dance hall.67L. Blance Young to O.C. Wenger, February 8, 1932, Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives.

Reports such as these inclined Wenger toward an all-out assault on the city's red-light district. As during wartime, Hot Springs's response to this federal ultimatum was regretful compliance. The death of the city's physician-mayor J.W. McClendon—"the leader of the wide-open town policy"—eased Washington's task. With the removal of this "obstacle," the PHS convinced local law enforcement officials to fall in line.68O.C. Wenger to David Robinson, April 18, 1921, Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives. By the summer of 1922, five brothels had been shut down; by 1923, their number had been reduced by half.69 Information on brothel closures comes from my own analysis of police dockets from the City of Hot Springs, 1920–1923. These documents can be found in the Garland County Historical Society Archives, Police Department Records, Vertical Files, Garland County Historical Society, Hot Springs, Arkansas. In 1918, before the initial crackdown on prostitution, sex-workers accounted for almost one-fifth of all criminal arrests in the city. These results bore out the federal government's conclusion that local personnel had been "very successful" in "eliminating houses of prostitution" in Hot Springs.70First Deficiency Appropriation Bill, 1921: Hearing before Subcommittee of the House Committee on Appropriations (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1921), 568.

This assessment proved premature. The interwar years brought new life to prostitution. While initially complying with the PHS, steep declines in revenue from saloons and bawdy houses prompted municipal officials to change their minds.71"Hard Sledding for Bankrupt City," Yearbook of the City Managers' Association 6 (1920): 85–6. In the late 1920s, the city's mayor "[threw] the town wide open" to prostitution, and in the next decade, cases of "female patients street-walking or soliciting" were "almost of daily occurrence."72Oliver C. Wenger, "The Transient-Indigent-Medical Problem at Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives. The clinic did little to oppose this challenge to federal authority. A 1934 visitor to the city remarked that Hot Springs was "the only national park where gambling, imbibing, and prostitution go unmolested."73Ray Hanley, A Place Apart: A Pictorial History of Hot Springs, Arkansas (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2011), 81; "Hot Springs Would Secede," Today 3 (1934): 23.

What explains this reversal? For one, it appears that clinic personnel had little appetite for prolonged conflict with the array of local forces (officials, doctors, and brothel owners) opposed to the abolition of prostitution. More important, however, were the interactions clinic personnel had with female patients—many of whom sold their bodies for sex while seeking VD treatment.

Consider the experience of a "young white woman" from Tennessee named "O.J." Orphaned since childhood, O.J. had grown up at the House of the Good Shepherd in Memphis. With "limited" opportunities, she then supported herself largely through prostitution—by which she contracted both syphilis and gonorrhea. Upon arriving in Hot Springs, O.J. found work as a boarding house maid. Subsequently accused by her landlady of "running around with men," O.J. found herself back on the streets. For the remainder of her stay, she supported herself through prostitution, a decision defended with three words: "I must eat." While concerned over the number of "boy friends" this "more than ordinarily attractive" woman had infected, Wenger sympathized with O.J.'s plight, explaining to his superiors that "she was a good patient and reported regularly for treatment." Summarizing her case, the PHS agent conceded that "it is hard to be chaste and hungry."74Wenger, "The Transient-Indigent-Medical Problem."

Interactions with patients like O.J. had a dramatic impact on clinicians, who came to accept prostitution not as an indication of immorality, but as a consequence of the adverse circumstances many female patients faced.75Wenger, Annual Report for 1923. In one of his earliest reports, Wenger spoke of the "large number of female patients" who arrived in Hot Springs with "no funds" and "no friends." With work "scarce" in the city, many of these women—in a "much discouraged" state—were "forced by dire necessity to support [themselves] by prostitution."76Oliver C. Wenger, "History of United States Public Health Clinic, Hot Springs, Arkansas," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives. The experiences of patients like O.J. were "not unique nor unusual, but exactly what goes on as these transients move across the country in their efforts to receive free medical service."77 "Any person who engages in travel," Wenger maintained, "may be the carrier of a communicable disease." "Every health officer knows," he reminded his superiors, "of instances, when, from one single source, hundreds and thousands of new cases have developed." Oliver C. Wenger, "The Indigent, Transient Problem and Its Relation to Public Health," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives. Criticizing those who argued that prostitution could not be tolerated, Wenger explained that "as social workers and health officers, we must change our own attitude and remember that we ourselves would become transients seeking medical services if they were not available at home. This is only natural."78Ibid. In connection with Wenger's apparent acceptance of prostitution in Hot Springs, it is interesting to note that while overseeing a VD control program in Puerto Rico during the Second World War, the PHS official was privately reprimanded for proposing "methods of registration and identification of prostitutes which seem quite out of line" with the federal government's official policy of repression. For more on this, see Surgeon General Parran to Senior Surgeon O.C. Wenger, March 23, 1942, Thomas Parran Papers, Series 1, Box 5, University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Hereafter, Parran Papers.

Consistent with his new understanding of prostitution, Wenger's interactions with female patients displayed a lack of moralizing. In lectures on how to "prevent a second infection," he endorsed the use of condoms and taught women "the value of prophylaxis and also contraceptives, or birth control methods." A typical lesson began with a discussion of female anatomy and concluded with demonstrations of birth control techniques.79In educating his patients on the use of contraceptives, Wenger was taking a risk. As he noted in a 1926 letter sent to Thomas Parran (the recently-appointed director of the PHS's Division of Venereal Diseases), "the whole subject of prophylaxis is T.N.T. at this stage of the game," and as such, advocating too forcefully on behalf of birth control measures "might innocently start some unwelcome comment"—particularly in the South. On account of this, Wenger generally advised that the PHS "let the State V.D. men do as they please"—another sign of the impact local forces had on the federal government's efforts. For more, see Oliver C. Wenger to Thomas Parran, October 23, 1926, Parran Papers. While initially concerned about how female patients would react to these frank methods, Wenger reported that "there has been no embarrassment on the part of the volunteer subjects or the patients looking on. The remarks and questions asked during the demonstrations are amazing."80O.C. Wenger to Dr. White, January 13, 1925, VD Division Records.

The clinic's female patients also encouraged Wenger to search for economic solutions to the country's VD epidemic. Consider the 1933 case of "Mrs. W." A white, college-educated woman who "came here all the way from old Mexico" after having been deserted by her husband (who infected her with syphilis) and having "suffered losses in the general depression." Upon arriving in Hot Springs, Mrs. W. initially stayed with a "colored friend." When this woman's relatives moved in, Mrs. W. informed clinic personnel that she was "planning to 'hitchhike' her way back to Nogales, Arizona," where friends would take her home. Believing such a trip would be "practically impossible," Wenger turned to local welfare agencies, "who agreed to pay half of her fare." The remainder was "made up by clinic personnel." Discussing her case in a report to his superiors, Wenger noted that "this is just another instance, in which, if maintenance could have been arranged for a longer period of time, the patient could have probably improved sufficiently to take her place again among her friends and be self-supporting."81Wenger, "The Transient-Indigent-Medical Problem."

Like O.J. and Mrs. W., most of the women who made their way to the Hot Springs clinic in the 1930s were white.82During the clinic's formative years, white women never accounted for more than one-fifth of the clinic's annual caseload. Between 1928 and 1936, however, their numbers steadily grew, reaching a peak of 2,353 in 1935—a year in which they represented nearly one-third of all patients treated. During the same period, African Americans' share of the clinic's annual caseload declined from 36.9 percent to 20.3 percent—a trend especially evident among females. O.C. Wenger, "Summary Statistical Data," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives. They received a much more sympathetic response than did the city's black health-seekers. Consider the case of Charley Wade Bradshaw. Shortly after entering the clinic on September 3, 1927, Bradshaw—a twenty-five year old black man employed as a porter by the Oklahoma City Railway Power House—was diagnosed with neurosyphilis and placed on a regimen of mercury. For six weeks, Bradshaw's savings enabled him to rent a room at a colored hotel, but on October 19, he was reported "AWOL." One year later, an Oklahoma City law firm supplied the reason for this abrupt departure. Coming to Hot Springs after company doctors "advised him that he had bad blood," Bradshaw left after running out of money for room and board. As an attorney informed Wenger, Bradshaw was "in a bad condition physically," and because he had "no means whatever," anyone who tried to help him "will have to do so at their expense."83Walter Martin to O.C. Wenger, March 2, 1928, VD Division Records.

Wenger apparently made no effort to pay for Bradshaw's expenses, despite his recognition of the socioeconomic inequalities that imperiled black health.84Between 1922 and 1932, the number of African American visitors listed in the "unskilled labor" category was "nearly twice as high" as the comparable figure for whites. O.C. Wenger, "An Analysis of 10,000 Cases of Syphilis," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives. While concurring that venereal diseases were "playing havoc within the Negro population of the country," he criticized those who interpreted these findings as evidence of African Americans' "absolute lack of morality." The observed differential between whites and blacks, commented Wenger, "does not mean that there is a considerable difference in the morals of these different groups." The critical variable was African Americans' "social economic status"—in particular, their "more limited" educational and employment opportunities. "When the social and economic backgrounds of the two races are considered," he concluded, "there seems to be little difference in the incidence of infection."85Oliver C. Wenger, "Analysis of 10,000 Cases of Syphilis," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives.

Improving black health-seekers' access to treatment required more than a rejection of the "syphilis-soaked negro" stereotype. When it came to removing institutional and economic barriers confronting African American VD patients, Wenger did little. He refused to challenge Hot Springs's adherence to Jim Crow, which confined African Americans to an "exterior observation" of all but two of the city's bathhouses. In addition to the "great disadvantage" they faced due to the "lack of proper accommodations in hotels and bathhouses," black patrons had fewer opportunities for securing therapeutic services than did whites. The Depression felled the one institution—the Woodmen of the Union Hospital—specifically catering to blacks.86 A.W. Hunton, "The American Carlsbad," The Voice of the Negro 3, no. 5 (1906–7): 331; C. Melnotte Wade, "Hot Springs—Its People," Colored American Magazine 10, no. 1 (1906): xviii; O.C. Wenger, "The United States Public Health Service Clinic at Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives; O.C. Wenger to Surgeon General, July 27, 1934, VD Division Records.

Black patients also faced the racial hostility of local physicians—some of whom worked in the PHS clinic. Believing that their higher rates of syphilis and gonorrhea stemmed from "the negro's almost absolute lack of morality and cleanliness," the resort's white doctors contended that southern blacks were "little better than animals with strong sexual passions."87 Thompson, Syphilis, 52. Some believed that emancipation constituted the primary cause of syphilis's spread "among the negro population of the South," as rampant promiscuity created a situation in which "the very existence of the race is threatened."88L.R. Ellis, "Address of the Chairman of the Section on Dermatology and Syphilology," Journal of the Arkansas Medical Society 6 (1909): 44; Loyd Thompson and Lyle B. Kingerly, "Syphilis in the Negro," American Journal of Syphilis 3 (1919): 396.

Racist attitudes were on display within the Hot Springs VD clinic. Admitted in July 1925, George Smith was a black man who came to the attention of local authorities after his arrest for "night prowling." While a judge ordered his release on the condition that he leave town, a Wassermann test revealed that Smith was infected with syphilis. Shortly after Wenger prevailed upon the city to permit his entrance into the PHS facility, trouble began. One day while receiving an injection of mercury, Smith reportedly became "impudent," and the doctor treating him "lost his temper and threatened to ruin" the man. Upon hearing of the incident, Wenger informed Smith to "remain away" from the clinic until the physician in question—a Dr. Abington—left. Though not expelling him, Wenger warned the doctor not to "cuss" the patients, and in his review of the case, the PHS official observed that Abington "was born and raised in the South, and [was] prejudiced toward all aggressive negroes."89O.C. Wenger to the Surgeon General, July 20, 1925, VD Division Records .

With the advent of the Great Depression, fewer and fewer men such as Charley Bradshaw and George Smith entered the Hot Springs clinic. As the economic misery of the 1930s increased, the proportion of black men and women admitted to the clinic declined precipitously; whereas in the 1920s, roughly one-third of the city's health-seekers were African American, by the middle part of the 1930s, this figure had fallen to about one-fifth. Those able to pay for a stay came later in the course of their infections than did whites, and in addition to presenting less curable forms of illness, they left Wenger's clinic much earlier than did white men and women.90On average, between 1922 and 1936, African American rates for tertiary syphilis were ten percentage points higher than those of their white counterparts, who also presented 8 percent more primary and secondary cases than did black syphilitics. O.C. Wenger, "Classification of Syphilis Cases, U.S. Public Health Service Clinic," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives. A 1940 study revealed that the average white syphilitic received twelve shots of Salvarsan, and blacks only nine.91Waugh and Milovich, "Severe Reactions," 390. For further evidence of the unfavorable therapeutic outcomes for black patients, see J.R. Waugh and W. Burns Jones, "Genito-Urinary Survey of 1,625 Male Patients, United States Public Health Service Venereal Disease Clinic, Hot Springs, Ark.," Journal of Venereal Disease Information 13, no. 1 (1932): 9.

Instances of racial discrimination continued. In 1941, a PHS officer reportedly entered a number of "reputable Negro business places" in nearby Texarkana, arresting several "young ladies," and then transporting them to Hot Springs for treatment—all without testing them for venereal disease.92"Officer Uses 'Gestapo' Methods: Texarkanians Terrorized, Business Houses Molested," Arkansas State Press, July 25, 1941, 1. Such tactics soured many black syphilitics on Hot Springs.93For likely racial discrimination, see Paul Carley, "Infection with Syphilis Masked by Gonorrhea," Journal of Venereal Disease Information 18, no. 2 (1937): 21–4. For their part, black newspapers discouraged readers from journeying into central Arkansas, noting that northern health resorts and spas were "more attractive than Hot Springs" on account of the latter's "awful...Jim Crow cars and other uncivilized offerings to the colored visitor."94"Negroes Can Bathe at French Lick Springs," The Michigan State News, Tuskegee Institute News Clippings File.

Clinic to Camp

From the beginning, clinic personnel were wary of attracting local citizens' ire. Hot Springs's patients frequently "[ran] into trouble with the police for housebreaking and robbing. " Local residents resoundingly objected to "the presence of such large numbers of indigent VD cases on the city streets."95"Hot Springs Judge Wroth over 'Dumping' of Indigent Diseased Transients in City," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives; Wenger, "The Transient-Indigent-Medical Problem"; O.C. Wenger to Surgeon General, July 27, 1934, VD Division Records. As early as the mid-1920s, Wenger called on the federal government to provide "some means of housing these indigent patients, or at least of providing them with sufficient food while they are under our care."96O.C. Wenger, "United States Conducts Clinic for Venereal Diseases," 103. Such aid never came.

During the Depression—as the city was "swamped with applicants seeking medical aid"—"begging, borrowing, and stealing" intensified.97Oliver C. Wenger to Taliaferro Clark, August 29, 1931, NPS Archives. Many of these applicants, wrote Wagner, belonged to a "much higher type group," individuals who in normal times would not have had to avail themselves of free, government-provided services.98O.C. Wenger, "The Transient-Indigent-Medical Program," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives. Aware of the ways his clinic was "causing objection and criticism from certain groups of citizens," in 1933 Wenger again asked for federal housing of indigent patients. His next budget included monies courtesy of the Arkansas Transient Bureau (ATB), a branch of the Federal Transient Bureau, to provide "free room and board" at "$1.00 per day per patient," as well as funds for hospitalization, telegrams, minor emergencies, and transportation home.99Ibid.

During its first month in operation, the ATB provided shelter, clothing, food, and medical attention to over 2,300 VD patients—black as well as white, female as well as male. The program reaped immediate dividends: according to state officials, only one year after implementing Wenger's "maintenance" plans, the number of venereal health-seekers leaving Hot Springs non-infectious increased by 38 percent.100R.O. Brunk, "Some Interesting Facts," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives. Echoing these sentiments, in January 1934, Wenger wired Washington praising the ATB for "giving out free room and board," noting that as a result of this "most of the old patients are remaining because they are getting free room and board and are taking more treatment."101Oliver C. Wenger to Dr. Vonderlehr, January 10, 1934, NPS Archives.

Figure 3: Salvarsan Injections Per Patient, 1922–1936

As diseased men and women descended onto Hot Springs, by early 1935 the ATB was providing for 4,000 diseased indigents.102McCully, "The United States Public Health Service." City officials claimed that many patients were "irresponsible as to their personal conduct"; every day, one local paper reported, twenty-five health-seekers faced arrest on charges of drunkenness and disturbing the peace.103Brunk, "Some Interesting Facts," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives; "Hot Springs Judge Wroth over 'Dumping' of Indigent Diseased Transients in City," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives. "If the federal government continues to invite the scum of the earth here," complained a judge to the PHS, "I guess we'll just have to move out and give the town to you."104"Hot Springs Judge," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives.

Hot Springs officials began resisting calls for assistance, even refusing to admit dozens of children whose parents were receiving treatment into the public school system. Despite Wenger's "most vehement protests," and despite repeated assurances that it was "perfectly safe" for these children to mingle with local children, municipal leaders were adamant.105Oliver C. Wenger, "A Plan for the Consolidation of all Medical Measures for Transient Relief in Hot Springs, Arkansas," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives. They began to push for the removal of the clinic's "undesirable" indigent transients.106"Council Approves New Transient Plan," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives.

Conceding that patients "cannot be left to roam at will and get into difficulties on the streets of Hot Springs," federal officials and the ATB considered construction of a camp on the city outskirts to house clinic patients and "give them wholesome occupation and recreation."107Antoinette Cannon, "Hot Springs Transient Program," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives. Initially, Wenger opposed these plans, but in order to "meet the needs of patients and the community," in 1934 the ATB began building a camp "for lone men who are under care in the United States Public Health Service clinic.108Ibid.

A year later, Camp Garraday opened on a thirty-three acre tract with a sixty-bed infirmary, nine barracks, kitchen, dining hall, and recreation building. During its first year, the ATB facility quartered five hundred white male transients.109O.C. Wenger, "A Plan for the Consolidation of all Medical Measures for Transient Relief in Hot Springs, Arkansas," September 5, 1935, NPS Archives. While these men—whom Wenger labeled the clinic's "hardest problem"—benefited from the "good food," shelter, immediate medical attention, and recreational opportunities provided directly by the federal government, white women and African Americans of both sexes continued to subsist under the old plan, by which they were "maintained in rooming and boarding houses throughout the city."110O.C. Wenger, "The United States Public Health Service Clinic at Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas," Oliver C. Wenger Papers, Box 1, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Archives.

Camp Garraday embodied the PHS's eugenic understanding of VD. While Wenger labeled white male patients a "problem," they were central to his ideology of "race conservation" and thereby worthy of privileges. Other patients might receive very modest financial aid, but they had to find sources of food and shelter, and felt the full force of the city's loathing. By contrast, white male patients received care on site, in a domiciliary setting. And Wenger sought to expand the camp's capabilities. In his 1936 budget, he recommended $55,320 for additional forms of support—including a butcher, a recreational supervisor, a housing director, a nursery, and a children's school (with principle and one teacher)—for Camp Garraday's residents.111Oliver C. Wenger, "A Plan for the Consolidation of All Medical Measures for Transient Relief in Hot Springs, Arkansas" (September 5, 1935), NPS Archives.

Wenger's plans never came to fruition. Local white citizens quickly and vehemently complained that Camp Garraday, "a Frankenstein monster," restored the "old stigma that Hot Springs is a place only for the treatment of venereal diseases." As the director of the Hot Springs Reservation explained, the PHS's efforts threatened to "ruin the results of the past hundred years of our history, to say nothing of the millions of dollars invested in the resort by private capital." The existence of Camp Garraday functioned to "make the place undesirable for pay patients."112As one local authority put it, developments of the early 1930s had given the health resort's more wealthy visitors the impression that "the transients being treated here were so numerous that [they] would overrun everything," and on account of this, the city had become "undesirable for pay patients." Thomas J. Allen to Arno B. Cammerer, July 23, 1934, NPS Archives.

Unable to overcome residents' objections to Wenger's maintenance program and the ATB's camp plan, the federal government terminated the Transient Bureau in 1936 and Camp Garraday ceased to house patients. Venereal health-seekers wishing treatment in Hot Springs were required to bring "sufficient funds available to pay their room and board over a period of at least ninety days."113John J. McShane to All Local Health Authorities, March 10, 1936, VD Division Records. For Oliver Wenger, who left Hot Springs in 1937 to take part in Chicago's Syphilis Control Program, it was a bitter ending. It appeared to him that Hot Springs was in no better shape than when he first arrived fifteen years earlier.

The same year Wenger left Hot Springs, Congress passed the National Venereal Disease Control Act. Allotting funds to the states, this legislation enabled a dramatic expansion in the nation's anti-venereal infrastructure. Arkansas soon felt the act's effects: prior to 1937 there were no state-run VD clinics here; by 1943, there were eighty-three. These new medical facilities treated fifteen thousand patients per year, far exceeding the heyday of the Hot Springs VD clinic.114"Venereal Disease Control," Arkansas Health Bulletin 1, no. 3 (1944): 6–9. In tandem with the mass production of penicillin in the 1940s, these developments led to a precipitous decline in the nationwide incidence of syphilis and gonorrhea. By the early 1950s, the country's VD "epidemic" had ended, and although rates for both syphilis and gonorrhea rose in subsequent decades, the government's model VD clinic would play no part in post-war developments.

Conclusion: Race, Hot Springs, and Tuskegee

The history of the Hot Springs VD clinic reveals how eugenics shaped the federal government's response to syphilis and gonorrhea. The facility's day-to-day operations show how the goal of "race conservation" structured patient experiences and outcomes. On account of the high volume of white syphilitics seeking admittance, clinic personnel became increasingly sympathetic to patients' circumstances and needs, and eventually, this sympathy manifested itself in a medical program that included free treatments as well as stipends for housing and food. While patients, regardless of race or sex, benefited from these extra-medical measures, it is unlikely the PHS would have launched such an approach to VD had not the primary beneficiaries been white males. The Camp Garraday transient center doled out special services to clinic patients because they were white men.

How did eugenics and scientific racism unfold at Hot Springs as compared with Tuskegee? As the failure of its venereological research program suggests, Hot Springs is a story about subjects becoming patients. In Tuskegee, the opposite occurred. What began as a series of mass treatment campaigns ended up as a horrific forty-year research program revolving around the denial of medical services. Tuskegee's creators tried to explain their complicity by invoking the Great Depression, claiming that their actions resulted from agency budget cuts that rendered additional funding for VD treatment impractical. However, just as the Depression deepened its hold, the PHS began pouring money into the Hot Springs clinic, whose patients were provided with drugs as well as with funds for food and shelter. The clientele at Wenger's clinic were primarily white; those enrolled in the Tuskegee study were black.

Race played a determining role in the PHS's attack on syphilis and gonorrhea. In broadening the scope of historical study beyond Tuskegee, and in particular by looking at the agency's policies toward white patients, the extent of the government's racialized response to VD becomes clearer.

About the Author

Elliott Bowen is a professor of history at Nazarbayev University and a historian of medicine and public health in the modern United States. His research explores the history of sexually transmitted diseases. Bowen is currently working on a book-length project about the history of Hot Springs, Arkansas.

Recommended Resources

Text

Bowen, Elliott. "Sin vs. Science? Rethinking Venereal Disease in Turn-of-the-Century America." Literature and Medicine 32, no. 2 (Fall 2014): 441–465.

Brandt, Allen M. No Magic Bullet: A Social History of Venereal Disease in the United States Since 1880. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Frith, John. "Arsenic—the 'Poison of Kings' and the 'Savior of Syphilis.'" Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health 21, no. 4 (2013): 11–17.

Frith, John. "Syphilis—Its early history and Treatment until Penicillin and the Debate on its Origins." Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health 20, no. 4 (2012): 49–58.

Keire, Mara L. For Business and Pleasure: Red-Light Districts and the Regulation of Vice in the United States, 1890–1933. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 2010.

Parascandola, John. Sex, Sin, and Science: A History of Syphilis in America. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2008.

Powell, Mary Lucas. The Myth of Syphilis: The Natural History of Treponematosis in North America. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2005.

Roberts, Samuel. Infectious Fear: Politics, Disease, and the Health Effects of Segregation. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Walls, Edwina. "Hot Springs Waters and the Treatment of Venereal Diseases: the U.S. Public Health Service Clinic and Camp Garraday." The Journal of the Arkansas Medical Society 91, no. 9 (1995): 433–437.

Zaffiri, Lorenzo, Jared Gardner, and Luis H. Toledo-Pereyra. "History of Antibiotics: From Salvarsan to Cephalosporins." Journal of Investigative Surgery 25, no. 2 (2012), 67–77.

Web

Barham, Ed, Katheryn Hargis, Jan Horton, Maria Jones, Vicky Jones, Kerry Krell, Ann Russell, Dianne Woodruff, and Amanda Worrell. 100 Years of Service: Arkansas Department of Health 1913–2013. Arkansas: Arkansas Department of Health, 2013. http://www.nphic.org/Content/Awards/2013/Print/ANNR-IH-AR-100years0402.pdf.

Dougan, Michael B. "Health and Medicine." The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture. Last modified January 13, 2017. http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?search=1&entryID=392.

Mooney, Graham. "History of Public Health." Online course, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health Open Courseware Course, Baltimore, 2005. http://ocw.jhsph.edu/index.cfm/go/viewCourse/course/HistoryPublicHealth/coursePage/index/.

"Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs)." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 15, 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/std/default.htm.

Wuebker, Erin. “Venereal Disease Visual History Archive.” Accessed October 12, 2017. https://vdarchive.newmedialab.cuny.edu/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | H.S. Cumming, Surgeon General, to Charles M. Pearce, State Health Commissioner, Oklahoma, January 29, 1936, General Records of the Venereal Disease Division, 1918–1936, 203.4, in RG 90, Records of the Public Health Service, 1912–1968, National Archives, College Park, Maryland. Hereafter VD Division Records. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Available federal census information indicates that in 1930, Ishcomer was married and had a least one son. Her husband appears to have been a mill hand but no occupation is listed for her. Exactly which of her conditions triggered resentment by clinic doctors is not clear. |

| 3. | For a brief overview of the Hot Springs VD clinic, see Edwina Walls, "Hot Springs Waters and the Treatment of Venereal Diseases: The U.S. Public Health Service Clinic and Camp Garraday," Journal of the Arkansas Medical Society 91, no. 9 (1995): 430–7. |