Overview

Evan C. Rothera reviews Brent M. S. Campney's This Is Not Dixie: Racist Violence in Kansas, 1861–1927 (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2015).

Review

"By branding the South as the racist section of the country," writes Brent Campney, "those narrating the identity of other sections have found a foil against which they can compare their own racial goodness. They can then deny, sanitize, or simply not see the profound anti-black racism in their own sections. Furthermore, when confronted by it, they can depict it as episodic or aberrant, something that occurred in but was not really of that place" (9). Long attentive to the history of white racial violence and lynching in the states of the former Confederacy,1See George Rable, But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984); Lou Faulkner Williams, The Great South Carolina Ku Klux Klan Trials 1871–1872 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1996); Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006); J. Michael Martinez, Carpetbaggers, Cavalry, and the Ku Klux Klan: Exposing the Invisible Empire During Reconstruction (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2007); Stephen Budiansky, The Bloody Shirt: Terror After the Civil War (New York: Penguin Group, 2008); LeeAnna Keith, The Colfax Massacre: The Untold Story of White Power, Black Terror, and the Death of Reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008); Charles Lane, The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, The Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2008); and Kimberly Harper, White Man's Heaven: The Lynching and Expulsion of Blacks in the Southern Ozarks, 1893–1909 (Fayetteville: The University of Arkansas Press, 2010). recent scholars have both widened their geographical frame and explored violence directed against racial and ethnic groups other than African Americans.2See William D. Carrigan and Christopher Waldrep, eds., Swift to Wrath: Lynching in Global Historical Perspective (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013); William D. Carrigan and Clive Webb, Forgotten Dead: Mob Violence Against Mexicans in the United States, 1848–1928 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013); and Michael J. Pfeifer, ed., Lynching Beyond Dixie: American Mob Violence Outside the South (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2013) Campney's book breaks new ground in revealing the hollowness of congratulatory comparisons between Kansas and the South while analyzing how Kansans created a "Free State Legend" and made themselves the not-South.

Campney insists that too many scholars reduce racist violence to lynching3Campney uses "racist violence" instead of "racial violence" to "underscore the implicit power dynamic: whites used racist violence to 'maintain social control over the black population through terrorism,'" (1). Here he follows Barbara J. Fields, "Whiteness, Racism, and Identity," International Labor and Working-Class History 60 (Fall 2001): 48–56. perhaps because lynching "seemed to define in the starkest terms the virulence of white racism, the vulnerability of blacks, and the brutality of the racial order" (1). He deploys a more capacious approach, encompassing sensational violence (lynchings, race riots, mobbing, killing-by-police, and homicides), threatened violence (threatened lynchings by mobs and intimations of violence by posses and crowds), and routine violence (many everyday types). He also highlights both black and white resistance.

Although "racial conservatives made up the majority of whites in the state" (14), Campney asserts, they did not have the education, resources, or influence of their moderate and radical white counterparts. Historians tend to minimize their voices, but Campney "examines the racist violence by means of which they fervently demonstrated their contempt for blacks" (14). Radical and moderate Kansans did not, by and large, approve of racist violence. However, by the 1880s, conservatives, usually through violence, compelled dissenters to abandon earlier promises of justice and equality.

Campney writes that beginning in 1861, white Kansans tolerated black fugitives from Missouri out of self-interest rather than beneficence and employed lynchings and other racist violence to stymie black suffrage, segregate public schools, and assert dominance.4In making this argument Campney critiques Nicole Etcheson, Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004), 229 and Robert G. Athearn, In Search of Canaan: Black Migration to Kansas, 1879–80 (Lawrence: Regents Press of Kansas, 1978), 75. Lynch mobs received widespread support from white communities. During Reconstruction, white Kansans employed racist violence to segregate public schools. Although traditionally defined as the five decades between the end of Reconstruction (1877) and the beginning of the Great Depression (1929), Campney widens the temporal bounds of the "lynching era" to include Reconstruction. In addition, when the black Exodusters arrived in Kansas in 1879, many whites employed violence to reinforce their supremacy.5"Exodus" refers to the migration of tens of thousands of African Americans from the South to Kansas. See Nell Irvin Painter, Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas after Reconstruction (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1976); Athearn, In Search of Canaan; and Charlotte Hinger, Nicodemus: Post-Reconstruction Politics and Racial Justice in Western Kansas (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016). Lynching "continued to provide a barometer for race relations," but other types of violence including enforced segregation and exclusion from towns and counties "played a highly publicized role in the savagery that defined the [eighteen] nineties" (91).

The spatial dimension of This Is Not Dixie is fascinating. Throughout the Midwest, and Kansas in particular, government agencies, residents, and writers framed racist violence as an exclusively southern phenomenon. The South became the demonized geography against which Kansans gauged their virtue and measured their superiority. When racist violence appeared, white Kansans usually considered it to be an imported contagion, claiming, for instance, "that white Texas drovers imported racist violence into the state's cattle towns" (34). White Kansans often asserted that "racist violence would always be foreign—no matter how common it was" (42).

Following the Civil War, white Kansans created the Free State Legend, reshaping the memory of the struggle in the 1850s into "a fight not only for white political and economic freedom but for the liberation of the slaves as well" (12). While utilizing violence to define racial boundaries, they spoke of Kansas as a "land of freedom and justice" (41). They argued that Kansas was a "worthy foil to the 'Negro-Hating South'" (72), even as they attacked the Exodusters. Pangs of conscience about the difference between the Free State Legend and everyday reality occasionally caused authorities to attempt to prevent violence. More commonly, however, after an episode of racist violence, white Kansans thumped their chests and decried the disease imported by Southerners. Kansans used the "mythology as a palliative to obscure their assault on blacks" and "routinely invoked the territorial origin myth as prima facie evidence of their commitment to racial equality" (99).

Deploying the Free State Legend, white Kansans "did internalize it to some degree, absorbing it into their geographical imaginations and thereby placing potent, if largely unconscious, constraints upon their own behavior" (166). African Americans appealed to it to "encourage whites' adherence to their own professed beliefs in racial justice" (177). Black men and women skillfully exploited white self-righteousness and shrewdly played on fears that racist violence would undermine the state's reputation.

African Americans cultivated their own version of the Free State Legend, sometimes juxtaposing memories of the South against Kansas and, despite plenty of evidence to the contrary, creating an "idyllic representation of the state" (177). Black newspapers frequently referred to Kansas as the land of freedom, especially in comparison with the Jim Crow South. Black Kansans determined to make Kansas live up to its promises.

Critically, this is not a story of helpless black people prostrate before savage whites. One of the most captivating and important components of This Is Not Dixie is Campney's discussion of black resistance by men and women, especially in self-defense organizations that sometimes succeeded in mounting jailhouse defenses to prevent lynchings. When black people defended a jailhouse, white men often preferred not to risk a confrontation.

Campney's discussion of black resistance challenges notions offered by some scholars that it was the defiant writings of New Negro intellectuals that first sparked a shift in black attitudes and that it took black World War I veterans to inspire a militant turn.6In making this argument, Campney builds on the work of Sundiata Keita Cha-Jua, "'A Warlike Demonstration': Legalism, Armed Resistance, and Black Political Mobilization in Decatur, Illinois, 1894–1898," The Journal of Negro History 83 (Winter 1998): 52–72. African Americans in Kansas articulated a defiant message and confronted white mobs decades earlier. The veterans of the 1920s "were not charting any radical new path; they were instead following in the well-traveled footsteps of their parents and grandparents" (199).

As African Americans resisted, so too did some whites. This Is Not Dixie offers several courageous examples. Mob violence offended the sense of civic order of many middle-class whites. White police officers, sometimes working with African Americans, began to thwart lynchings. This seeming progress, however, proved hollow. Killings-by-police escalated while lynchings declined, allowing the state to wrest control from mobs, effectively diminishing unpredictability while achieving the same repressive purpose.

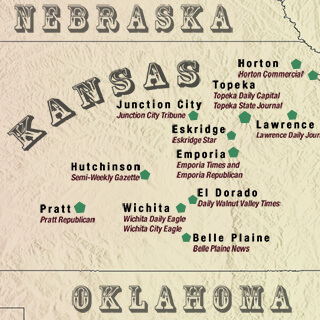

Although Campney might have delved deeper into manuscript collections and sought out more contemporary correspondence, This Is Not Dixie is supported by thorough research in the state's many newspapers. The book is full of challenging and provocative ideas. It critiques, for instance, the too-simple "what's the matter with Kansas" analysis. This analysis, articulated in Thomas Frank's What's the Matter with Kansas, unquestioningly accepts the Free State Legend and asserts that Kansas "doesn't do racism."7Thomas Frank, What's the Matter with Kansas: How Conservatives Won the Heart of America (New York: Metropolitan, 2004), 179. Campney deftly illustrates how a compelling narrative benefitted white people, but also how African Americans used the Free State Legend to sway white behavior. His examination of black resistance complicates older notions about accommodation and militancy. In expanding the geography of racist violence, This Is Not Dixie will appeal to anyone interested in US race relations from the era of the Civil War and Reconstruction through the 1920s.

About the Author

Evan C. Rothera is a Postdoctoral Teaching Fellow in the History Department at The Pennsylvania State University and a member of the Richards Civil War Era Center. Rothera's dissertation analyzes civil wars and reconstructions in the United States, Mexico, and Argentina in the period 1860–1880.

Cover Image Attribution:

Bird's eye view of the city of Topeka, the capital of Kansas, 1869. Lithograph by A. Ruger. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Geography and Maps Division, loc.gov/resource/g4204t.pm002310.Recommended Resources

Text

Berg, Manfred. Popular Justice: A History of Lynching in America. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2011.

Carrigan, William D. and Christopher Waldrep, eds. Swift to Wrath: Lynching in Global Historical Perspective. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013.

Carrigan, William D. and Clive Webb. Forgotten Dead: Mob Violence Against Mexicans in the United States, 1848–1928. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Hall, Jacquelyn Dowd. Revolt Against Chivalry: Jessie Daniel Ames and the Women's Campaign Against Lynching. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993.

Pfeifer, Michael J., ed. Lynching Beyond Dixie: American Mob Violence Outside the South. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

———. Rough Justice: Lynching and American Society: 1874–1947. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Waldrep, Christopher. African Americans Confront Lynching: Strategies of Resistance from the Civil War to the Civil Rights Era. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2009.

Wood, Amy Louise. Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890–1940. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Web

Berman, Mark. "Even more black people were lynched in the U.S. than previously thought, study finds." Washington Post, February 10, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2015/02/10/even-more-black-people-were-lynched-in-the-u-s-than-previously-thought-study-finds.

Carrigan, William D. and Clive Webb. "When Americans Lynched Mexicans." New York Times, February 20, 2015. https://nyti.ms/2k5iiya.

Falco, Ed. "When Italian immigrants were 'the other'." CNN, July 10, 2012. http://www.cnn.com/2012/07/10/opinion/falco-italian-immigrants/index.html.

"Lynching in America: Racial Terror Lynchings." Equal Justice Initiative. 2017. https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/explore.

Mock, Brentin. "Why Memorializing America's History of Racism Matters." CITYLAB. July 6, 2015. https://www.citylab.com/design/2015/07/why-memorializing-americas-history-of-racism-matters/397781/.

"New Report Examines Lynchings And Their Legacy In The United States." NPR. Last modified February 10, 2015. http://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2015/02/10/385263536/new-report-examines-lynchings-and-their-legacy-in-the-united-states.

Solly, Meilan. "Brooklyn Museum's 'Legacy of Lynching' Exhibition Confronts Racial Terror." Smithsonian Magazine. August 7, 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/brooklyn-museums-legacy-lynching-exhibition-confronts-racial-terror-180964288.

Williams, Kidada E. "Centuries of Violence." Slate. June 19, 2015. http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/history/2015/06/charleston_church_shooting_for_black_americans_dylann_storm_s_attack_is.html.

Woodruff, Judy, Hari Sreenivasan and Brian Stevenson. "Lynching memorial aims to help U.S. acknowledge a history of terror." PBS NEWSHOUR. December 19, 2016. http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/lynching-memorial-aims-help-u-s-acknowledge-history-terror.

Similar Publications

| 1. | See George Rable, But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984); Lou Faulkner Williams, The Great South Carolina Ku Klux Klan Trials 1871–1872 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1996); Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006); J. Michael Martinez, Carpetbaggers, Cavalry, and the Ku Klux Klan: Exposing the Invisible Empire During Reconstruction (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2007); Stephen Budiansky, The Bloody Shirt: Terror After the Civil War (New York: Penguin Group, 2008); LeeAnna Keith, The Colfax Massacre: The Untold Story of White Power, Black Terror, and the Death of Reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008); Charles Lane, The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, The Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2008); and Kimberly Harper, White Man's Heaven: The Lynching and Expulsion of Blacks in the Southern Ozarks, 1893–1909 (Fayetteville: The University of Arkansas Press, 2010). |

|---|---|

| 2. | See William D. Carrigan and Christopher Waldrep, eds., Swift to Wrath: Lynching in Global Historical Perspective (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013); William D. Carrigan and Clive Webb, Forgotten Dead: Mob Violence Against Mexicans in the United States, 1848–1928 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013); and Michael J. Pfeifer, ed., Lynching Beyond Dixie: American Mob Violence Outside the South (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2013) |

| 3. | Campney uses "racist violence" instead of "racial violence" to "underscore the implicit power dynamic: whites used racist violence to 'maintain social control over the black population through terrorism,'" (1). Here he follows Barbara J. Fields, "Whiteness, Racism, and Identity," International Labor and Working-Class History 60 (Fall 2001): 48–56. |

| 4. | In making this argument Campney critiques Nicole Etcheson, Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004), 229 and Robert G. Athearn, In Search of Canaan: Black Migration to Kansas, 1879–80 (Lawrence: Regents Press of Kansas, 1978), 75. |

| 5. | "Exodus" refers to the migration of tens of thousands of African Americans from the South to Kansas. See Nell Irvin Painter, Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas after Reconstruction (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1976); Athearn, In Search of Canaan; and Charlotte Hinger, Nicodemus: Post-Reconstruction Politics and Racial Justice in Western Kansas (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016). |

| 6. | In making this argument, Campney builds on the work of Sundiata Keita Cha-Jua, "'A Warlike Demonstration': Legalism, Armed Resistance, and Black Political Mobilization in Decatur, Illinois, 1894–1898," The Journal of Negro History 83 (Winter 1998): 52–72. |

| 7. | Thomas Frank, What's the Matter with Kansas: How Conservatives Won the Heart of America (New York: Metropolitan, 2004), 179. |